#it’s as important as my flight logbooks to me

Text

I love being an adult it’s yaaaaaaas here’s funds to spend 20 hours handcrafting my favorite fanfic into a hardbound book with intricate themed embroidery on the front…

#nononono what’s crazy is she did it for free and I just paid shipping#but I shoved some money down her throat anyways cause this is like worth more than gold to me#I literally need to buy a fireproof safe for it#it’s as important as my flight logbooks to me

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Spaceship Short Stories

Yeah why not. Title is self-explanatory. I'll be bringing back my aborted plan for a spaceship story in favour of this because I want to. Also, I will be changing and retconning past work in this as I go. Don't expect anything to stay the same.

Intro.

This is the official logbook of the Vchern'ixt, or Merchant and Delivery Ship 382. (382-MDS). We are, as our work tag suggests, an interplanetary merchant ship. This logbook will almost certainly be used by the crew, and knowing my crew, will not be taken seriously. I can only hope it will provide actual information, and I will hopefully find the time to add actual updates between the crew entries.

Entry 1: 218-4-7 (Kaylie - Pilot)

First week on the ship! Not much happened this week, few deliveries, some unnecessarily (but fun) dangerous asteroid-dodging. I think everyone else is still getting used to a human in board, they're fairly cautious around me. To be honest, I would be as well! I think their previous pilot was a lot more cautious than me. They've been watching me, though. Curious but cautious. I've tried to make some friends, be nice to people, but it's kinda hard when everyone half expects you to explode at any moment.

Truly, the worst part is that they don't have coffee here. I'll make sure to fix that with the first paycheck I get, Captain said that "you can spend your own money on your comforts. I'll spend the ship's money on the ship." So they're no help. Anyways, paycheck is in two days, and we dock for supplies at Kerroi-825B in... Whenever our orbits get close, so I'll be able to get my coffee then! For now, I'll live with the mimicry that Grömerg makes.

Entry 2: 218-4-10 (Grömerg - Medic, Chef)

My coffee is not bad, is it? I do not know if the taste is as it should be, though it smells like the sample you gave me. I'm sorry if it is [untranslatable]

Translator suggestions: Subpar, worse than typical, less than.

Entry 3: 218-4-12 (Kaylie)

It's not! I just prefer real coffee over synthetic, not a problem with you at all!

Update: finally got my coffee machine! And I remembered to buy coffee beans this time! It didn't take as long as I thought to find the "Human Items" section of Kerroirå Market (Fun fact: that's "Kerroi Market Market in Tychfing), and I was able to grab my coffee making items (coffee ingredients?) In time to not be left behind by the crew! Yay!

In other news, I was able to pick up a roll of duct tape and a knife for our beloved cleaning robot. Now I just have to fit Stabby with a camera to record everyone else's reactions to him. He is now one with the hivemind of Stabbies. Oh, and I grabbed the stuff I was actually supposed to. The boring stuff. It was heavy, but some people helped me load the boxes into the ship!

Entry 4: Galactic Year 218, Standard Lunar Cycle (SLC) 4, Standard Solar Cycle (SSC) 14 [218-4-14] (Ky'tchas - Secretary, Accountant)

Kaylie, what is your new creation for? It has caused several minor injuries, and I don't understand the purpose of the "laugh track." Or the confetti. Why do these only occur when it stabs someone? Are they incentive for violence?

Additionally, I will include the "boring stuff," or our pickup for the next delivery. We have picked up:

14 Planetary Leap Drives, 10 Warp Cores, 2 Wormhole Accessors, 24 Guard-8.6 Androids, 48 Holo-Screen 18.5s, and 36 Extragravitory Flight Suits.

These are important things to record. Kaylie, as the one who ordered some of the parts, you should be the one to relay them to me. As it is, you should have placed the order through me in the first place, since it is my job to place orders and file them.

You're new, so I assume you haven't heard anyone explicitly state this, though the captain should have during your viewing and explanation of the ship. Either way, I expect any further orders to be placed though me.

Entry 5: 218-4-18 (Grömerg)

Kaylie? Is it alright if I make a request of you? Please, I beg, slow down when flying. The food almost did not survive our last warp-jump.

IN PROGRESS

#space australia#science fiction#humans are space australians#humans are space weirdos#stabby the roomba#Sergeant Stabby#Spaceship log#Feat. Confused aliens#coffee#Humans need coffee to live#Kaylie slow down please#Humans are reckless#Just like as a species

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Preparing for Colombia

Jean-André is in Marseille, Marisa is in Zurich. We just have one week left before going to Cali in Colombia.

How do we feel ? A bit stressed but so much excited ! This is a strange mix of feelings, just exactly like before jumping into the water from a cliff : you really want to do it but something is holding you back. Surely the fear that we’ll miss our friends, the fear of leaving our comfort zone to go to the unknown.

A lot of questions in our heads, how will it be ??

How nice will be the people around us ?

How will be the university and our offices ?

Do we have a sufficient knowledge to work on cyanide remediation in a river ?

Will we succeed in constructing the Showerloop in a real bathroom ?

Can we visit Colombia during the weekends ? Where to go ?

How will we meet our new friends ?

All that we know for now is the plan of our two projects :

The first one concerns a cyanide contamination in a stream in Mondomo, a town 70km from Cali. One of the traditional Colombian activities is making starch from manioc. But manioc contains cyanide. There is no problem when you eat it because it’s cooked and the cyanide evaporates, but in the extraction process of starch, all the cyanide goes into the effluents, and is released into streams. So we need to evaluate how contaminated the stream is and find the most appropriate solution to treat it, taking into account technical aspects but also, economical, sociological and cultural aspects. This is our Master’s Internship and we had the chance to be funded by the “Ingénieurs du Monde” association of EPFL, that promotes exchanges and cooperation in the Global South Countries.

View of Mondomo © DaNiEl.O [1]

The second one is the “Showerloop 4 Dev” project, more personal. This year, we built in the Student Krativity and Innovation Laboratory (SKIL) at EPFL a cyclic shower that reuses and treats water in real time to use only 10 liters per shower. This is an Open Source technology invented by Jason Selvarajan that we wanted to implement in Colombia and therefore, we applied to the Development Impact Grants of the Cooperation and Development Center (CODEV) at EPFL. The CODEV center works on the link between the Global South and the Global North, researching how innovation and technologies can lead to a better human development by responding to today’s global issues and UN’s Sustainable Development Goals. We had the honor to earn from this grant the funding of 3 showers for the Sports Center of the Universidad del Valle.

Jason Selvarajan's Showerloop © Jason Selvarajan

So much challenges we will face. But for now, the biggest challenge is : pack our bags.

We have to take all the stuff we need for one year of adventure. What do we have to take ?

We had different ways to do it :

Jean-André:

“Not a lot of clothes ! Not a lot of clothes!” I was saying to myself. Do you know this feeling when you go 10 days in a place, thinking that you didn’t take a lot of clothes, and finally your luggage is more than 23kg and you have to wear 6 shirts and 3 jackets to be able to register it and go to the plane ? I wanted to avoid it. I preferred to take a few things, like 5 shirts, 3 pants, and if I need some things, I would buy it there. But one thing that I’m sure of is that I want to go climbing and hiking in Colombia. I took a large backpack, my hiking shoes, my climbing shoes, my harness and all the camping stuff : a tent, sleeping bags, air mattresses, cooking stove, pots and pans, utensils, flashlight, lantern, small solar panels and appropriate cold weather gear for snow capped peaks. I know I surely forgot things, but then we will improvise.

I spent this final week before the flight studying papers on cyanide & manioc, and refreshing my Spanish : watching movies and series in Spanish like Amando a Pablo, Casa de Papel or Narcos, listening to and translating some Latin songs like Calle 13, and reading Spanish authors like Isabel Allende or Gabriel Garcia Marquez.

Marisa:

As for me, I wanted to take the minimum of clothes possible, just as Jean-André. However, I’m really bad at this, and I felt like I wouldn’t succeed in selecting only the most important things. Since Colombia has a great variety of landscapes going from beautiful beaches to stunning views over snowy mountains and rainforests, I took clothes for each of these situations; short as well as long pants with some shirts, swimwear but also a thicker jacket if I go hiking in colder areas.

Since I really like hiking, I took my hiking shoes, a backpack and also a sleeping bag in case I have the opportunity to camp. A Swiss army knife had also a place in my bag : you never know when you can use it. Apart from that, I just accomplished a scuba diving course in Thailand and discovered that I love this activity and the underwater world. I heard that there are some nice spots to go diving in Colombia as well, therefore I took my logbook with me which is a small book where you can write down all the dives you accomplished.

I spent the last few days with family and friends and prepared the internship by reading papers about cyanide treatment and the Showerloop. But now it’s finally time to go to the airport. At that moment I still couldn’t realize that we were really going to Colombia.

But now it is, here it is... We are each in our respective airports, ready to take the plane after a big hug to our parents. Still asking to ourselves what are we going to discover in Colombia…

Departure from the airport

[1] http://ec.geoview.info/vista_del_pueblo_desde_las_montanas,19776917p

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

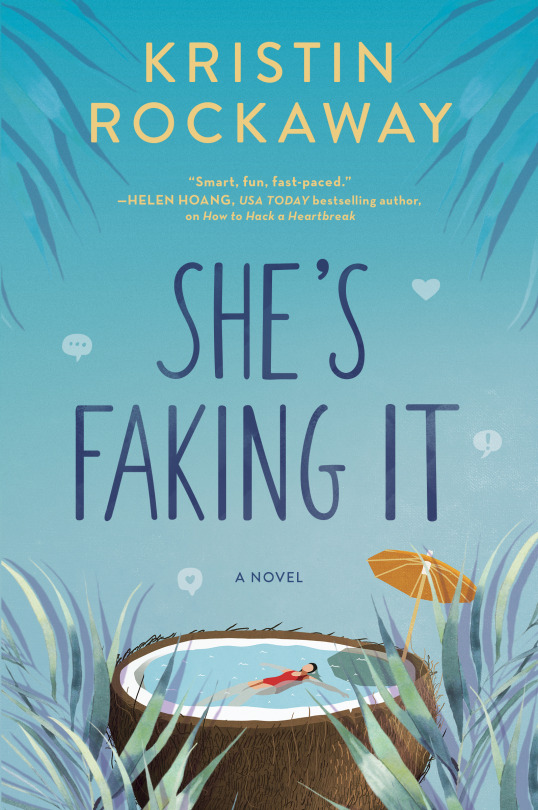

Blog tour! I present to you some info and an excerpt from She’s Faking It by Kristin Rockaway.

She’s Faking It

Kristin Rockaway

FICTION/Romance/Contemporary

Trade Paperback | Graydon House Books

On Sale: 6/30/2020

978152580464

$15.99

$19.99 CAN

You can’t put a filter on reality.

Bree Bozeman isn’t exactly pursuing the life of her dreams. Then again, she isn’t too sure what those dreams are. After dropping out of college, she’s living a pretty chill life in the surf community of Pacific Beach, San Diego…if “chill” means delivering food as a GrubGetter, and if it means “uneventful”.

But when Bree starts a new Instagram account — @breebythesea — one of her posts gets a signal boost from none other than wildly popular self-help guru Demi DiPalma, owner of a lifestyle brand empire. Suddenly, Bree just might be a rising star in the world of Instagram influencing. Is this the direction her life has been lacking? It’s not a career choice she’d ever seriously considered, but maybe it’s a sign from the universe. After all, Demi’s the real deal… right?

Everything is lining up for Bree: life goals, career, and even a blossoming romance with the chiseled guy next door, surf star Trey Cantu. But things are about to go sideways fast, and even the perfect filter’s not gonna fix it. Instagram might be free, but when your life looks flawless on camera, what’s the cost?

BUY LINKS:

Harlequin

Amazon

Apple Books

Barnes & Noble

Books-A-Million

Google Play

IndieBound

Kobo

Kristin Rockaway is a native New Yorker with an insatiable case of wanderlust. After working in the IT industry for far too many years, she traded the city for the surf and chased her dreams out to Southern California, where she spends her days happily writing stories instead of software. When she's not writing, she enjoys spending time with her husband and son, and planning her next big vacation.

SOCIAL LINKS:

http://kristinrockaway.com/

Facebook: /KristinRockaway

Twitter: @KristinRockaway

Instagram: @KristinRockway

Excerpt

From Chapter Two

“Don’t these books make your purse really heavy? There’s gotta be some app where you can store all this information.”

“Studies show you’re more likely to remember things you’ve written by hand, with physical pen and paper.” She reached across my lap and opened the glove compartment, removing a notebook with an antiqued photograph of a vintage luxury car printed on the cover. “For example, this is my auto maintenance log. Maybe if you’d kept one of these, like I told you to, we wouldn’t be in this predicament right now.”

I loved Natasha, I really did. She was responsible and generous, and without her I’d likely be far worse off than I already was, which was a horrifying thought to consider. But at times like this, I wanted to grab her by the shoulders and shake the shit out of her.

“A maintenance log wouldn’t have helped me.”

“Yes, it would have. Organization is about more than decluttering your home. It’s about decluttering your mind. Making lists, keeping records—these are all ways to help you get your life in order. If you’d had a maintenance log, this problem wouldn’t have caught you off guard in the middle of your delivery shift. You’d have seen it coming, and—”

“I saw it coming.”

“What?”

“This didn’t catch me off guard. The check engine light came on two weeks ago.” Or maybe it was three.

“Then why didn’t you take it to the mechanic?” She blinked, genuinely confused. Everything was so cut-and dried with her. When a car needed to be serviced, of course you called the mechanic.

That is, if you could afford to pay the repair bill.

Fortunately, she put two and two together without making me say it out loud. “Oh,” she murmured, then bit her lip. I could almost hear the squeak and clank of wheels turning in her head as she tried to piece together the solution to this problem. No doubt it included me setting up a journal or logbook of some sort, though we both knew that would be pointless. The last time she’d tried to set me up with a weekly budget planner, I gave up on day two, when I realized I could GrubGetter around the clock for the rest of my life and still never make enough money to get current on the payments for my student loans. You know, for that degree I’d never finished.

But Natasha was a determined problem solver. It said so in her business bio: “Natasha DeAngelis, Certified Professional Organizer®, is a determined problem solver with a passion for sorting, purging, arranging, and containerizing.” My life was a perpetual mess, and though she couldn’t seem to be able to clean it up, that didn’t stop her from trying. Over and over and over again.

“I’ll pay for the repairs,” she said.

“No.” I shook my head, fending off the very big part of me that wanted to say yes. “I can’t take any money from you.”

“It’s fine,” she said. “Business is booming. I’ve got so much work right now that I’ve actually had to turn clients away. And ever since Al introduced that new accelerated orthodontic treatment, his office has been raking it in. We can afford to help you.”

“I know.” Obviously, my sister and her family weren’t hurting for cash. Aside from her wildly successful organizing business, her husband, Al, ran his own orthodontics practice. They owned a four-bedroom house, leased luxury cars, and took triannual vacations to warm, sunny places like Maui and Tulum. They had a smart fridge in their kitchen that was undoubtedly worth more than my nonfunctioning car.

But my sister wasn’t a safety net, and I needed to stop treating her like one. She’d already done so much for me. More than any big sister should ever have to do.

“I just can’t,” I said.

“Well, do you really have any other choice?” There was an edge to Natasha’s voice now. “If you don’t have a car, how are you going to work?”

“I’ll figure something out.” The words didn’t sound very convincing, even to my own ears. For the past four years, all I’d done was deliver food. I had no other marketable skills, no references, no degree.

I was a massive failure.

Tears pooled in my eyes. Natasha sighed again.

“Look,” she said, “maybe it’s time to admit you need to come up with a solid plan for your life. You’ve been in a downward spiral ever since Rob left.”

She had a point. I’d never been particularly stable, but things got a whole lot worse seven months earlier, when my live-in ex-boyfriend, Rob, had abruptly announced he was ending our three-year relationship, quitting his job, and embarking on an immersive ayahuasca retreat in the depths of the Peruvian Amazon.

“I’ve lost my way,” he’d said, his eyes bloodshot from too many hits on his vape pen. “The Divine Mother Shakti at the Temple of Eternal Light can help me find myself again.”

“What?” I’d been incredulous. “Where is this coming from?”

He’d unearthed a book from beneath a pile of dirty clothes on our bed and handed it to me—Psychedelic Healers: An Exploratory Journey of the Soul, by Shakti Rebecca Rubinstein.

“What is this?”

“It’s the book that changed my life,” he’d said. “I’m ready for deep growth. New energy.”

Then he’d moved his belongings to a storage unit off the side of the I-8, and left me to pay the full cost of our monthly rent and utilities on my paltry GrubGetter income.

I told myself this situation was only temporary, that Rob would return as soon as he realized that hallucinating in the rainforest wasn’t going to lead him to some higher consciousness. But I hadn’t heard from him since he took off on that direct flight from LAX to Lima. At this point, it was probably safe to assume he was never coming back.

Which was probably for the best. It’s not exactly like Rob was Prince Charming or anything. But being with him was better than being alone. At least I’d had someone to split the bills with.

“Honestly,” she continued, “I can’t stand to see you so miserable anymore. Happiness is a choice, Bree. Choose happy.”

Of all Natasha’s pithy sayings, “Choose happy” was the one I hated most. It was printed on the back of her business cards in faux brush lettering, silently accusing each potential client of being complicit in their own misery. If they paid her to clean out their closets, though, they could apparently experience unparalleled joy.

“That’s bullshit, and you know it.”

She scowled. “It is not.”

“It is, actually. Shitty things happen all the time and we have no choice in the matter. I didn’t choose to be too broke to fix my car. I work really hard, but this job doesn’t pay well. And I didn’t choose for Rob to abandon me to go find himself in the Amazon, either. He made that choice for us.”

I almost mentioned the shittiest thing that had ever happened to Natasha or to me, a thing neither of us had chosen. But I stopped myself before the words rolled off my lips. This evening was bad enough without rehashing the details of our mother’s death.

“Sometimes things happen to us that are beyond our control,” Natasha said, her voice infuriatingly calm. “But we can control how we react to it. Focus on what you can control. And it does no good to dwell on the past, either. Don’t look back, Bree—”

“Because that’s not where you’re going. Yes, I know. You’ve said that before.” About a thousand times.

She took a deep breath, most likely to prepare for a lengthy lecture on why it’s important to stay positive and productive in the face of adversity, but then a large tow truck lumbered onto the cul-de-sac and she got out of the car to flag him down.

Grateful for the interruption, I ditched the casserole on her dashboard and walked over to where the driver had double-parked alongside my car.

“What’s the problem?” he asked, hopping down from the cab.

“It won’t start,” I said, to which Natasha quickly followed up with, “The check engine light came on several weeks ago, but the car has not been serviced yet.”

He grunted and popped the hood, one thick filthy hand stroking his braided beard as he surveyed the engine. Another grunt, then he asked for the keys and tried to start it, only to hear the same sad click and whine as before.

“It’s not the battery.” He leaned his head out of the open door. “When was the last time you changed your timing belt?”

“Uh… I don’t know.”

Natasha shook her head and mouthed, Maintenance log! in my direction but I pretended not to see.

The driver got out and slammed the hood shut. “Well, this thing is hosed.”

“Hosed?” My heart thrummed in my chest. “What does that mean? It can’t be fixed?”

He shrugged, clearly indifferent to my crisis-in-progress. “Can’t say for sure. Your mechanic can take a closer look and let you know. Where do you want me to tow it?”

I pulled out my phone to look up the address of the mechanic near my apartment down in Pacific Beach. But Natasha answered before I could google it up.

“Just take it to Encinitas Auto Repair,” she said. “It’s on Second and F.”

“You got it,” he said, then retreated to his truck to fiddle with some chains.

Natasha avoided my gaze. Instead, she focused on calling a guy named Jerry, who presumably worked at this repair shop, and told him to expect “a really old Civic that’s in rough shape,” making sure to specify, “It’s not mine, it’s my sister’s.”

I knew she was going to pay for the repairs. It made me feel icky, taking yet another handout from my big sister. But ultimately, she was right. What other choice did I have?

The two of us stayed quiet while the driver finished hooking up my car. After he’d towed it away down the cul-desac and out of sight, Natasha turned to me. “Do you want to come over? Izzy’s got piano lessons in fifteen minutes, you can hear how good she is now.”

Even though I did miss my niece, there was nothing I wanted to do more than go home, tear off these smelly clothes, and cry in solitude. “I’ll take a rain check. Thanks again for coming to get me.”

“Of course.” She started poking at her phone screen. A moment later, she said, “Your Lyft will be here in four minutes. His name is Neil. He drives a black Sentra.” A quick kiss on my cheek and she was hustling back to her SUV.

As I watched Natasha drive away, I wished—not for the first time—that I could be more like her: competent, organized, confident enough in my choices to believe I could choose to be happy. Sometimes I felt like she had twenty years on me, instead of only six. So maybe instead of complaining, I should’ve started taking her advice.

Excerpted from She’s Faking It by Kristin Rockaway, Copyright © 2020 by Allison Amini. Published by Graydon House Books.

0 notes

Text

Aviation Headhunters - Your Trading Education Is The Key To Success

We Brits are renowned for our slapstick humorous. And we tend to associated with some other nationalities as lacking in wit; or having a humour prevent. So how do we define different senses of comedy?

Image Source:

Pilot Headhunters - 20 Things You Don't Want to Hear About Airline

Beliefs are filters by which we gaze at world. Doesn't meam they are reality, but additionally shape our view of reality. Whatever our belief, they will surely allow supporting evidence in the course of. Therefore, if you believe the world is flat, your belief will permit in information that supports that belief and will reject anything that does not. Some forms of "vague" information the assumption will twist and distort to support itself.

Image Source:

Airline Headhunters - 19 Things You Don't Want to Hear About Airline

Give yourself the best chance possible by staying with it for finding a good amount of time. I mean if you are training to become an pilot headhunters you wouldn't expect become fully competent and flying those huge jumbos using months would you!

youtube

Video Source:

Headhunter Aviation - What Everyone Is Saying About Airline

Why mention personality categories? I mention them because if you know how to understand each family that you talk to, you'll be more winning. You will know what they like and dislike, thus helping them person to love you greater!

Airline Headhunting Services - The Untold Secret To Mastering Airline In Just 3 Days

Only 120 minutes earlier, I tied down N757KN over a ramp and my instructor signed my logbook for the first time. It would be a 1.4 hour flight with one landing in VFR day cases. The feeling that I'd flown an aircraft, which in fact had now been in an accident and resulted in the deaths of 2 people, was overwhelming.

Reward yourself- Do something for yourself as reward for your practicing. I recently upgraded the ingredients on my bike for each the hard I've spent Hire Pilot Headhunters over weight loss year. It felt good to give something back, instead of insisting on working troublesome. I know I'll have more pleasant riding my bike obviously you can serves as being a pleasant reminder for my efforts.

I i do hope you understand in case you to help "keep your eye on the prize," you Need A Airline Headhunters need to a value! You need a goal that you have to aim for. And just knowing the goal help you to you focus. Will you hit it every a while? No. But without a goal you will never hit the!

With the financial troubles prevalent throughout america today, it's common knowledge us face uncertainty within jobs too. Today (Sept 15th 2008) the Dow tumbled 500 points, the biggest one day loss in seven months. Merrill Lynch is eradicate and Lehman Brothers is certainly bankrupt. Together with the bubble bursting your housing market and the financial woes of Fannie Mae, these are troubling times indeed.

Offer to speak more at a job so in your volunteer work. Get known as "the speaker". Offer flying insects other speakers, chair opertation or MC a panel discussion.

One Monday morning, I stop to talk with Gary. Gary pulls dreams of his 7-year old daughter the actual his purse. The two spent the weekend together in order to church comes with the theatre. Gary transgresses into his 20-year experience each morning service, traveling all around the globe. He shares the importance of teamwork involving military and talks in respect to the friends he lost, fighting in Kosovo. He shares his vision of rediscovering the reassurance of school to stay an pilot headhunters. I share my dreams of wanting to dedicate yourself to myself.

A medical career is unquestionably one on the highest paying careers about the. However, becoming a doctor or a surgeon demands whole lot of time and price.

The strengths of the Green's are that these organized, planners, accurate, and persistent automobiles follow-through. Their weaknesses might be being over-analytical, hard to please, depressed (I wonder why), and lonely.

This is a hard one, I be aware! I am on the online market place every day and get, will be of advertising is astonishing. Brokers are offering free education (fox in the hen house if i hear you ask me), forums of all different trading styles and points of view. Gurus pushing their system as "the one" that could possibly make you some money. How an individual get through all that noise?

If Used to go back to sales, what might I sell in this economy? Not at all cars! With gas prices as high as they are, I doubt individuals are beating along the doors in the local SUV dealer. I would imagine that the home improvement industry additionally in trouble so automobiles selling flooring is over.

"Perhaps it is silly, yet is something we have to tell ourselves every day," he stated. "I had already come forth with last plot for your book as i was still flying airfreight but it remained for me personally to set goals: an utter page count, a chapter outline, coupled with a word goal for each chapter. Once organized, this 'only' an issue of fleshing out craze. I say 'only' tongue-in-cheek because it still took two more years to finish, even once I had adopted an increasingly disciplined system. I was even that could add a denouement to deliver the story into the modern day time along with the first edition was published just leading to the deregulation for the securities and banking industries led into the total meltdown of our economy.

Author Name:- Shreya Mehta

Address:- 104 Esplanade ave 120,

Pacifica, CA

Mobile No:- +1 917-668-8461

0 notes

Text

Flying over mountains isn’t as scary (or hard) as you might think

“I shopped the Strip at Mahoney Creek only to see its windsocks voting in opposite directions.” (Julie Boatman/)

This story originally featured in the May 2020 issue of Flying Magazine.

My relationship with the mountains began on hikes with my family, camping trips up into the farthest corners of Glacier National Park that could be reached with a 7-year-old (me) and a toddling 4-year-old (my little brother) in close formation. We took what we could carry in our little packs—supplemented heavily with the resources my parents stuffed into their own.

Fast-forward to my early flight-instructing years in Colorado, where one of my greatest joys was introducing pilots to the high country—famously high-altitude airports like Leadville, Telluride and Aspen. The “real” backcountry beckoned, though, and about 15 years ago, I took a condensed, one-on-one mountain flying course with well-known backcountry instructor Lori MacNichol, through McCall Mountain Canyon Flying Seminars. The flights I made there cemented my love for the high country and, more so than that, provided me with a skill set that could be applied to much of my everyday flying.

Indeed, these lessons that the mountains bring to us know no gender, age or aviation background. So, when Christina Tindle from WomanWise Aviation Adventures dropped me a note on Twitter, asking my interest in joining them for an upcoming seminar in Cascade, Idaho, I was intrigued by two things: how flying with like-minded pilots would enhance my experience (or detract from it) and how much I would recall from my previous time flying into the Idaho wilderness.

A psychologist and counselor by occupation—and backcountry pilot—Tindle launched a series of seminars in 2011 with a fly-in to Smiley Creek, Idaho. In 2019, she conducted four events in Idaho and Colorado, focusing on backcountry flying but also touching on other areas of flight based on the requests of participants, including upset and recovery training, aerobatics, floatplane flying, and primary tailwheel instruction.

“These lessons the mountains bring to us know no gender, age or aviation background. ” (Julie Boatman/)

Setting goals

I knew this aviation seminar would be different when Tindle sent me a pre-event registration packet that included an overview with the quote, “If the shoe fits, you’ll dance a lot longer.” While the questionnaire accompanying the notes asked me to list standard items such as my flight time and recency of experience—and relative comfort flying in the backcountry—it also asked an open-ended question, “What do you want from your experience at WWAA?”

You could respond with a simple answer, or you could dive in more philosophically. Given that the registration form also noted that we would be formulating Life Flight plans, the intention with the question was clearly broader than simply probing our need to improve our confined-airstrip-landing skills.

Because I would be a speaker at the seminar, giving a presentation on coping with life’s “go-arounds” (often mistakenly referred to as “failures”), I left my answer generic, knowing I’d address the very topic I wanted to work on—extrapolating the confidence I’ve often gained from flying into my life on the ground—in my talk with the group.

A careful study of the terrain and airport information before you fly is critical—but takes on even more significance in the mountains. (Julie Boatman/)

Preparation and planning

Weather in Cascade in the third week of September can offer up anything from summer-like temps and density-altitude concerns to drizzly clouds and mountain-obscuring ceilings—or even a blizzard. I scheduled two days of instruction according to the forecast, knowing I could add an aerobatic flight or some tailwheel practice as the actual conditions allowed.

To balance the flying time, Tindle scheduled briefings from the instructor corps in the afternoons and evenings. For example, in one evening, Bob Del Valle of Hallo Flight Training (based in Priest River, Idaho) covered key concepts, such as engine failure after takeoff and accelerated stalls, as well as decision-making skills tuned to the environment in which we’d fly.

I spent my first day of flying with Fred Williams, an instructor who splits his time between Cascade and Reno, Nevada. He offered up his Kitfox with large-format tires for our flying—an airplane I’d flown only briefly with a friend in the more urbane environs of airpark-rich Florida.

View this post on Instagram

Highlights from the “Lessons From The Mountains” appearing in May 2020 FLYING. #instaaviation #avgeek #avgeeks #explore #aviation #flying #pilots #airplanes #goflying #aviationlovers #flyingmagazine #flyingmag #pilotsofinstagram #mountainflying #backcountry #backcountryflying #idahoflying #flyidaho #kitfox

A post shared by Flying Magazine (@flyingmagazine) on May 6, 2020 at 10:28am PDT

We briefed the flights in detail before launching, with a careful look at the airport diagrams and sectional charts, as well as the beta put together on each approach by a long list of experienced (and mostly successful) mountain pilots before us. Williams quizzed me on general concepts such as performance and high-country macro- and microweather to determine my background and review any areas I needed to address. Because my previous time flying in the true backcountry had been more than a decade ago (and different from flying at high-elevation yet improved airports in the Mountain West such as Santa Fe, New Mexico, or Steamboat Springs, Colorado), there was much ground to cover.

Understanding performance is paramount to mountain ops—whether it involves a new-to-you airplane, as was the Kitfox for me, or an old friend like the Cessna 182, which I would fly on day two. I looked forward to flying a made-for-the-mountains machine like Williams’ Kitfox, which has a 115 hp turbocharged Rotax 914 UL engine up front coupled with a Garmin G3X Touch integrated flight deck in the panel, about $150,000 as equipped. As a special light-sport aircraft, the Kitfox in this configuration keeps training costs reasonable while, at the same time, offering some of the latest technology and safety features.

We knew wind would likely become a factor after lunch—very common when flying in the mountains, regardless of the season—so we planned to keep a watchful eye on the wind vector shown on the G3X as we crossed passes on our way out and back.

“A Canyon Turn takes advantage of the fact that reducing airspeed decreases the radius of your turn.” (Julie Boatman/)

The practice area

Once briefed, we launched into blue and headed east to the practice area, in the valley hosting the Landmark, Idaho, airstrip (0U0). Before reaching the airport vicinity, Williams had me practice canyon turns in the broad valley, slowing down bit by bit to tighten them up. A canyon turn takes advantage of the fact that reducing your airspeed decreases the radius of your turn. If you execute a turn using a 30-degree bank at a near-cruise, density-altitude-adjusted groundspeed of 120 knots, the radius of your turn is 2,215 feet. At a speed near VA for many single-engine airplanes—say, 90 knots—you take up a lot less real estate, at 1,246 feet. If you can safely reduce your speed to 60 knots, that figure drops to 553 feet, and you can just about execute a 180-degree turn in 1,100 feet laterally. Use of flaps can help maintain a slower speed—making a huge difference when you contemplate a course reversal below canyon walls.

But those take practice to execute well. In Del Valle’s briefing, he had gone over the increased stall speed inherent with a turn of increased bank. With a bank angle of zero, let’s say your airplane has a stall speed (VS) of 60 knots. At 30 degrees of bank, that speed increases 10 percent to 66 knots; at 45 degrees of bank, it’s up to 72 knots. Because the Kitfox’s VS was much lower than 60 knots—try 49 mph with no flaps—we had a lot of room to play with, but still the smaller the bank, the less the chance we’d run into accelerated-stall territory. A good canyon turn is a balance of these aspects.

Surveying the strip—what some pilots call “shopping,” a term I first heard from MacNichol 15 years ago and in common usage among Idaho pilots—takes practice, too. Flying an extra traffic pattern gives you time to ferret out the details. Sometimes, you have to do this a lot higher than a standard traffic-pattern altitude, and you might not have sight of the strip during the approach until you’re on short final.

At Landmark, we had a relatively wide-open valley in which to maneuver as we gauged the status of its 4,000-foot-long, 100-foot-wide surface. As we worked through the day, flying to Indian Creek (S81) and Thomas Creek (2U8), we would need progressively more-inventive ways to survey the landing site before making our approach. On day two in the 182, we would do the same with instructor Stacey Burdell, scoping the scene at Stanley (2U7), Smiley Creek (U87), Idaho City (U98) and Garden Valley (U88), consecutively.

Checking the actual weather against the forecast also proved most important, especially because of the winds at ridge-top level contradicting those at the surface—or even at the ends of the same runway. With Williams on day one, I shopped the strip at Mahoney Creek (0U3) only to see its windsocks voting in opposite directions. As much as I wanted to land there and tag another new strip in my logbook, we left it for another day. We bounced around enough on the way back to Cascade (U70) to validate my choice.

Most visitors to the Frank Church River of No Return Wilderness float or hike in, but flying yourself offers an unmatched perspective. (Julie Boatman/)

A stabilized approach

If you have this image of a backcountry pilot making crazy maneuvers to “make it” to a landing, dispel them from your mind right now. If you have any sense, you won’t accept anything less than a stabilized approach—and you’ll bail out early if you can’t maintain your airspeed and sight picture.

That said, the stabilized approach to a backcountry strip looks a little different than the one you might use in normal ops. This stems directly from the fact many mountain strips are one-way-in runways and have a “point of no return,” after which you must make the landing. A super-low-speed, power-off, short-field approach doesn’t offer the same margins for adjustment at the last minute that the backcountry approach does.

We practiced at Landmark—which has no point of no return because of its position in the valley—setting up a steep, low-power descent at a moderate rate, with full flaps in the Kitfox (think 30 degrees if you were flying a Cessna 172) and a speed at 1.2 to 1.3 times VSO, which correlates to about 55 mph indicated in the Kitfox. This configuration offers the ability to use more or less power if needed and modify the descent rate to avoid landing short—or long.

The key is to lock this in well before you reach your predetermined go-around point. If you don’t have the configuration in place and stable, you need to execute the go-around before that point of no return, or you risk everything. One of the approaches on day two was not well-stabilized, at Garden City, and it drove home the necessity of staying diligent about this practice—and being locked and loaded to go around if you’re too high and too fast at the key position, rather than forcing the approach.

Instructors Fred Williams and Danielle Maniere have fun in the Kitfox. (Julie Boatman/)

Life lessons

There’s an aspect of facing and conquering the unknown that carries over into the rest of your experience. The mountains are personal to me, and returning to them at a perfect time in my life, when I needed a shot of self-confidence, made all the difference in the world.

As weather drew in on day three, we bagged the airport activities for a hike into a nearby hot springs as the snow fell around us. The camaraderie was real as we navigated slippery rocks, and it would continue on in the aviation friendships I made that week. Our Plan B was just fine—and executing it reiterated the joy of taking advantage of life’s sharp turns. A disappointment became an opportunity to enjoy the natural beauty of a place we could access through general aviation. That’s another lesson that feels particularly poignant now as we face uncertainties ahead in life.

On the last evening of the seminar, the group encapsulated our plans for the coming days, weeks and months into concrete goals. Mine was simple: to keep flying. To keep exploring new places only an airplane can reach. To tap into that well of confidence-building stuff that only learning to fly has provided me. And that too is something every pilot can take away.

An approach into Garden Valley. (Julie Boatman/)

Mountain skills you can use every day

Pay attention to micrometeorology—and understand how fast the weather can change. In both the mountains and the lowlands, the environment immediately surrounding an airport can funnel winds and generate up- and downdrafts worthy of note, along with localized clouds and reduced visibility.

A stabilized approach is a safe approach. While you might use a different technique for your approach to a “normal” runway, setting a configuration and rate of descent to have in place by the time you’re at 500 feet agl—or higher—will stack the deck in your favor for a better landing.

Practice and plan for a go-around every time. In the backcountry, your go-around decision point might not be over the runway, or even on short final. Committing to a go-around plan, and knowing when you’ll trigger it, is vital. This holds true with every single landing you attempt.

The go/no-go decision continues throughout the flight. While you may consider the flight launched once you’re airborne, you’re always in a position to return to the place you just left, divert, or come up with some alternative to the plan you had in mind. This mental flexibility may very well save your life someday.

Take the right equipment. Save room (and weight) for a well-stocked flight bag—one that holds an extra layer of clothing, a hat, a first-aid kit, food and water, and other emergency supplies. Landing out, even in the flatlands, can leave you far from assistance.

Required reading

Two books guided my research, and a host of content online supports the topics they cover.

If there’s a primary textbook for flying in the high country, Mountain, Canyon, and Backcountry Flying by Amy L. Hoover and R.K. “Dick” Williams is it. Hoover has been flying the Idaho backcountry since 1989 and started teaching mountain flying in 1992 while working as a backcountry air-taxi pilot. She’s an original co-founder of McCall Mountain Canyon Flying Seminars. For the book she teamed up with pilot legend and author Dick Williams, who started training pilots in the backcountry in 1985. It’s available through Aviation Supplies and Academics.

For those who want their mountain flying in concise form, seek out a copy of Mountain Flying by Sparky Imeson, published in 1987 by Airguide Publications. Imeson, who ironically died in a March 2009 accident involving his Cessna 180 in the mountains, founded Imeson Aviation in 1968 at the Jackson Hole Airport in Wyoming. His wisdom—and the website, mountainflying.com—lives on, disseminating his vast knowledge of the techniques and decision-making critical to flying safely in the backcountry.

More aviation adventures

Tindle plans more WomanWise Aviation Adventures for 2020, though at press time they remain in flux because of general travel concerns in the spring, which we all hope to have dissipate by summer. Tindle said in March, “[I’m planning] September 6 to 10 in Steamboat Springs, Colorado, for high-mountain flying, aerobatics and spin [training], and soaring, which is new. [Then it’s] October 25 to 29 in Moab, Utah, for backcountry flying, aerobatics and spin [training], and ballooning—also new.”

Check womanwiseaviationadventures.com for more details.

Also, look to Fred Williams’ Adventure Flying LLC for the wide range of flight training he provides in Cascade, Idaho, and Reno, Nevada, both in the Kitfox or in the aircraft you bring (contact Williams for details via advflying.com). Bob Del Valle offers instruction in Sandpoint, Idaho, as well as around Montana and Washington (halloflighttraining.com). Sam Davis offers instruction in aerobatics, as well as upset prevention and recovery, in the Heber City, Utah, area through Pilot Makers Advanced Flight Academy (pilotmakers.com).

0 notes

Text

Flying over mountains isn’t as scary (or hard) as you might think

“I shopped the Strip at Mahoney Creek only to see its windsocks voting in opposite directions.” (Julie Boatman/)

This story originally featured in the May 2020 issue of Flying Magazine.

My relationship with the mountains began on hikes with my family, camping trips up into the farthest corners of Glacier National Park that could be reached with a 7-year-old (me) and a toddling 4-year-old (my little brother) in close formation. We took what we could carry in our little packs—supplemented heavily with the resources my parents stuffed into their own.

Fast-forward to my early flight-instructing years in Colorado, where one of my greatest joys was introducing pilots to the high country—famously high-altitude airports like Leadville, Telluride and Aspen. The “real” backcountry beckoned, though, and about 15 years ago, I took a condensed, one-on-one mountain flying course with well-known backcountry instructor Lori MacNichol, through McCall Mountain Canyon Flying Seminars. The flights I made there cemented my love for the high country and, more so than that, provided me with a skill set that could be applied to much of my everyday flying.

Indeed, these lessons that the mountains bring to us know no gender, age or aviation background. So, when Christina Tindle from WomanWise Aviation Adventures dropped me a note on Twitter, asking my interest in joining them for an upcoming seminar in Cascade, Idaho, I was intrigued by two things: how flying with like-minded pilots would enhance my experience (or detract from it) and how much I would recall from my previous time flying into the Idaho wilderness.

A psychologist and counselor by occupation—and backcountry pilot—Tindle launched a series of seminars in 2011 with a fly-in to Smiley Creek, Idaho. In 2019, she conducted four events in Idaho and Colorado, focusing on backcountry flying but also touching on other areas of flight based on the requests of participants, including upset and recovery training, aerobatics, floatplane flying, and primary tailwheel instruction.

“These lessons the mountains bring to us know no gender, age or aviation background. ” (Julie Boatman/)

Setting goals

I knew this aviation seminar would be different when Tindle sent me a pre-event registration packet that included an overview with the quote, “If the shoe fits, you’ll dance a lot longer.” While the questionnaire accompanying the notes asked me to list standard items such as my flight time and recency of experience—and relative comfort flying in the backcountry—it also asked an open-ended question, “What do you want from your experience at WWAA?”

You could respond with a simple answer, or you could dive in more philosophically. Given that the registration form also noted that we would be formulating Life Flight plans, the intention with the question was clearly broader than simply probing our need to improve our confined-airstrip-landing skills.

Because I would be a speaker at the seminar, giving a presentation on coping with life’s “go-arounds” (often mistakenly referred to as “failures”), I left my answer generic, knowing I’d address the very topic I wanted to work on—extrapolating the confidence I’ve often gained from flying into my life on the ground—in my talk with the group.

A careful study of the terrain and airport information before you fly is critical—but takes on even more significance in the mountains. (Julie Boatman/)

Preparation and planning

Weather in Cascade in the third week of September can offer up anything from summer-like temps and density-altitude concerns to drizzly clouds and mountain-obscuring ceilings—or even a blizzard. I scheduled two days of instruction according to the forecast, knowing I could add an aerobatic flight or some tailwheel practice as the actual conditions allowed.

To balance the flying time, Tindle scheduled briefings from the instructor corps in the afternoons and evenings. For example, in one evening, Bob Del Valle of Hallo Flight Training (based in Priest River, Idaho) covered key concepts, such as engine failure after takeoff and accelerated stalls, as well as decision-making skills tuned to the environment in which we’d fly.

I spent my first day of flying with Fred Williams, an instructor who splits his time between Cascade and Reno, Nevada. He offered up his Kitfox with large-format tires for our flying—an airplane I’d flown only briefly with a friend in the more urbane environs of airpark-rich Florida.

View this post on Instagram

Highlights from the “Lessons From The Mountains” appearing in May 2020 FLYING. #instaaviation #avgeek #avgeeks #explore #aviation #flying #pilots #airplanes #goflying #aviationlovers #flyingmagazine #flyingmag #pilotsofinstagram #mountainflying #backcountry #backcountryflying #idahoflying #flyidaho #kitfox

A post shared by Flying Magazine (@flyingmagazine) on May 6, 2020 at 10:28am PDT

We briefed the flights in detail before launching, with a careful look at the airport diagrams and sectional charts, as well as the beta put together on each approach by a long list of experienced (and mostly successful) mountain pilots before us. Williams quizzed me on general concepts such as performance and high-country macro- and microweather to determine my background and review any areas I needed to address. Because my previous time flying in the true backcountry had been more than a decade ago (and different from flying at high-elevation yet improved airports in the Mountain West such as Santa Fe, New Mexico, or Steamboat Springs, Colorado), there was much ground to cover.

Understanding performance is paramount to mountain ops—whether it involves a new-to-you airplane, as was the Kitfox for me, or an old friend like the Cessna 182, which I would fly on day two. I looked forward to flying a made-for-the-mountains machine like Williams’ Kitfox, which has a 115 hp turbocharged Rotax 914 UL engine up front coupled with a Garmin G3X Touch integrated flight deck in the panel, about $150,000 as equipped. As a special light-sport aircraft, the Kitfox in this configuration keeps training costs reasonable while, at the same time, offering some of the latest technology and safety features.

We knew wind would likely become a factor after lunch—very common when flying in the mountains, regardless of the season—so we planned to keep a watchful eye on the wind vector shown on the G3X as we crossed passes on our way out and back.

“A Canyon Turn takes advantage of the fact that reducing airspeed decreases the radius of your turn.” (Julie Boatman/)

The practice area

Once briefed, we launched into blue and headed east to the practice area, in the valley hosting the Landmark, Idaho, airstrip (0U0). Before reaching the airport vicinity, Williams had me practice canyon turns in the broad valley, slowing down bit by bit to tighten them up. A canyon turn takes advantage of the fact that reducing your airspeed decreases the radius of your turn. If you execute a turn using a 30-degree bank at a near-cruise, density-altitude-adjusted groundspeed of 120 knots, the radius of your turn is 2,215 feet. At a speed near VA for many single-engine airplanes—say, 90 knots—you take up a lot less real estate, at 1,246 feet. If you can safely reduce your speed to 60 knots, that figure drops to 553 feet, and you can just about execute a 180-degree turn in 1,100 feet laterally. Use of flaps can help maintain a slower speed—making a huge difference when you contemplate a course reversal below canyon walls.

But those take practice to execute well. In Del Valle’s briefing, he had gone over the increased stall speed inherent with a turn of increased bank. With a bank angle of zero, let’s say your airplane has a stall speed (VS) of 60 knots. At 30 degrees of bank, that speed increases 10 percent to 66 knots; at 45 degrees of bank, it’s up to 72 knots. Because the Kitfox’s VS was much lower than 60 knots—try 49 mph with no flaps—we had a lot of room to play with, but still the smaller the bank, the less the chance we’d run into accelerated-stall territory. A good canyon turn is a balance of these aspects.

Surveying the strip—what some pilots call “shopping,” a term I first heard from MacNichol 15 years ago and in common usage among Idaho pilots—takes practice, too. Flying an extra traffic pattern gives you time to ferret out the details. Sometimes, you have to do this a lot higher than a standard traffic-pattern altitude, and you might not have sight of the strip during the approach until you’re on short final.

At Landmark, we had a relatively wide-open valley in which to maneuver as we gauged the status of its 4,000-foot-long, 100-foot-wide surface. As we worked through the day, flying to Indian Creek (S81) and Thomas Creek (2U8), we would need progressively more-inventive ways to survey the landing site before making our approach. On day two in the 182, we would do the same with instructor Stacey Burdell, scoping the scene at Stanley (2U7), Smiley Creek (U87), Idaho City (U98) and Garden Valley (U88), consecutively.

Checking the actual weather against the forecast also proved most important, especially because of the winds at ridge-top level contradicting those at the surface—or even at the ends of the same runway. With Williams on day one, I shopped the strip at Mahoney Creek (0U3) only to see its windsocks voting in opposite directions. As much as I wanted to land there and tag another new strip in my logbook, we left it for another day. We bounced around enough on the way back to Cascade (U70) to validate my choice.

Most visitors to the Frank Church River of No Return Wilderness float or hike in, but flying yourself offers an unmatched perspective. (Julie Boatman/)

A stabilized approach

If you have this image of a backcountry pilot making crazy maneuvers to “make it” to a landing, dispel them from your mind right now. If you have any sense, you won’t accept anything less than a stabilized approach—and you’ll bail out early if you can’t maintain your airspeed and sight picture.

That said, the stabilized approach to a backcountry strip looks a little different than the one you might use in normal ops. This stems directly from the fact many mountain strips are one-way-in runways and have a “point of no return,” after which you must make the landing. A super-low-speed, power-off, short-field approach doesn’t offer the same margins for adjustment at the last minute that the backcountry approach does.

We practiced at Landmark—which has no point of no return because of its position in the valley—setting up a steep, low-power descent at a moderate rate, with full flaps in the Kitfox (think 30 degrees if you were flying a Cessna 172) and a speed at 1.2 to 1.3 times VSO, which correlates to about 55 mph indicated in the Kitfox. This configuration offers the ability to use more or less power if needed and modify the descent rate to avoid landing short—or long.

The key is to lock this in well before you reach your predetermined go-around point. If you don’t have the configuration in place and stable, you need to execute the go-around before that point of no return, or you risk everything. One of the approaches on day two was not well-stabilized, at Garden City, and it drove home the necessity of staying diligent about this practice—and being locked and loaded to go around if you’re too high and too fast at the key position, rather than forcing the approach.

Instructors Fred Williams and Danielle Maniere have fun in the Kitfox. (Julie Boatman/)

Life lessons

There’s an aspect of facing and conquering the unknown that carries over into the rest of your experience. The mountains are personal to me, and returning to them at a perfect time in my life, when I needed a shot of self-confidence, made all the difference in the world.

As weather drew in on day three, we bagged the airport activities for a hike into a nearby hot springs as the snow fell around us. The camaraderie was real as we navigated slippery rocks, and it would continue on in the aviation friendships I made that week. Our Plan B was just fine—and executing it reiterated the joy of taking advantage of life’s sharp turns. A disappointment became an opportunity to enjoy the natural beauty of a place we could access through general aviation. That’s another lesson that feels particularly poignant now as we face uncertainties ahead in life.

On the last evening of the seminar, the group encapsulated our plans for the coming days, weeks and months into concrete goals. Mine was simple: to keep flying. To keep exploring new places only an airplane can reach. To tap into that well of confidence-building stuff that only learning to fly has provided me. And that too is something every pilot can take away.

An approach into Garden Valley. (Julie Boatman/)

Mountain skills you can use every day

Pay attention to micrometeorology—and understand how fast the weather can change. In both the mountains and the lowlands, the environment immediately surrounding an airport can funnel winds and generate up- and downdrafts worthy of note, along with localized clouds and reduced visibility.

A stabilized approach is a safe approach. While you might use a different technique for your approach to a “normal” runway, setting a configuration and rate of descent to have in place by the time you’re at 500 feet agl—or higher—will stack the deck in your favor for a better landing.

Practice and plan for a go-around every time. In the backcountry, your go-around decision point might not be over the runway, or even on short final. Committing to a go-around plan, and knowing when you’ll trigger it, is vital. This holds true with every single landing you attempt.

The go/no-go decision continues throughout the flight. While you may consider the flight launched once you’re airborne, you’re always in a position to return to the place you just left, divert, or come up with some alternative to the plan you had in mind. This mental flexibility may very well save your life someday.

Take the right equipment. Save room (and weight) for a well-stocked flight bag—one that holds an extra layer of clothing, a hat, a first-aid kit, food and water, and other emergency supplies. Landing out, even in the flatlands, can leave you far from assistance.

Required reading

Two books guided my research, and a host of content online supports the topics they cover.

If there’s a primary textbook for flying in the high country, Mountain, Canyon, and Backcountry Flying by Amy L. Hoover and R.K. “Dick” Williams is it. Hoover has been flying the Idaho backcountry since 1989 and started teaching mountain flying in 1992 while working as a backcountry air-taxi pilot. She’s an original co-founder of McCall Mountain Canyon Flying Seminars. For the book she teamed up with pilot legend and author Dick Williams, who started training pilots in the backcountry in 1985. It’s available through Aviation Supplies and Academics.

For those who want their mountain flying in concise form, seek out a copy of Mountain Flying by Sparky Imeson, published in 1987 by Airguide Publications. Imeson, who ironically died in a March 2009 accident involving his Cessna 180 in the mountains, founded Imeson Aviation in 1968 at the Jackson Hole Airport in Wyoming. His wisdom—and the website, mountainflying.com—lives on, disseminating his vast knowledge of the techniques and decision-making critical to flying safely in the backcountry.

More aviation adventures

Tindle plans more WomanWise Aviation Adventures for 2020, though at press time they remain in flux because of general travel concerns in the spring, which we all hope to have dissipate by summer. Tindle said in March, “[I’m planning] September 6 to 10 in Steamboat Springs, Colorado, for high-mountain flying, aerobatics and spin [training], and soaring, which is new. [Then it’s] October 25 to 29 in Moab, Utah, for backcountry flying, aerobatics and spin [training], and ballooning—also new.”

Check womanwiseaviationadventures.com for more details.

Also, look to Fred Williams’ Adventure Flying LLC for the wide range of flight training he provides in Cascade, Idaho, and Reno, Nevada, both in the Kitfox or in the aircraft you bring (contact Williams for details via advflying.com). Bob Del Valle offers instruction in Sandpoint, Idaho, as well as around Montana and Washington (halloflighttraining.com). Sam Davis offers instruction in aerobatics, as well as upset prevention and recovery, in the Heber City, Utah, area through Pilot Makers Advanced Flight Academy (pilotmakers.com).

0 notes

Text

Living in a Sailboat Tree House - Stuck on Dry Dock (March 14 -April 13, 2019)

youtube

Cabedelo, Brazil, South America

For the past several weeks, we have been stuck on dry dock in the shipyard at Marina Jacaré Village here in Cabedelo, Brazil. It feels so strange to be on the boat, but not in the water. Living on dry dock is like living in a tree house. It’s not easy. It’s not convenient. But like everything else we have experienced so far, it’s another adventure.

During the past month, I took a two-week break and headed to our land home in Gulf Shores, Alabama, U.S.A. to work a little and visit with family and friends. I had not been home since before we set sail on this journey seven months ago.

Meanwhile, in Brazil, Maik continued to work on at least eight major projects during this past month—all while living in our sailboat tree house. Most of these projects are still ongoing. Here is a recap of our last month in Cabedelo, Brazil and Alabama, USA.

Thursday, 14 March 2019

We continue to be completely inspired by the other sailors we meet and their stories. We have been in Cabedelo for so long we have seen many sailors come and go. I’ve said this many times, but it’s important to say it again—with sailors, it’s never goodbye. We always know that there is a chance we will see our sailing friends again somewhere in the world at some point. This will make even more sense if you read all of this logbook entry, as well as previous entries.

In my last blog, I mentioned our friends, Robin and Philemon, who recently sailed down to Patagonia on the southern tip of South America. They sailed around Cape Horn and then sailed for 40 straight days up to Cabedelo. They have a very cool steel ship, Bekwaipa. This is a French word that Robin learned from his grandmother. Loosely translated, it means “the opposite of not stable.”

We were walking by their boat on the pontoon while they were working outside on boat projects and invited us onboard for a tour. This is not a bright, shiny, or fancy boat. The green and white steel structure is covered in rust and in some parts of the cabin there are no walls, only open insulation. But this is a STABLE boat, so the name fits! Their inside layout is similar to Seefalke. It has the appearance of being messy and cluttered, but it’s very organized for them. They have creative rigs everywhere, including a long board with their depth sounder attached to the end. They simply hang this off the back stern when they need to test the depth of the water. It’s simple and unsophisticated, but it works.

They have surfboards on board and look like typical vagabond surfer dudes. They are so cool and are living a cool, free lifestyle. They are making plans to head back home for a month and then return here to sail to the Azores next.

That evening we ate dinner at our favorite outdoor meat-stick truck and eventually drew a crowd. We were joined by Robin and Philemon, Sophie and Tobias, and Felix and Emeline. Everyone but Maik drank Caipirinhas (the official Brazilian cocktail) and talked for hours about the addiction of sailing and the sailing lifestyle. There is a unique and instant connection with other sailors who love this lifestyle.

Friday, 15 March 2019

Christoph surprised us at breakfast with our finished cockpit boards. They had all been sanded and oiled and look brand new!

Again, we worked all day in marina. This is a very open and social area for the sailors here. The washrooms and showers are here, as well as a small diner with a limited menu, and a laundry service operated by a sweet Brazilian woman, Annabella. Most important, there are tables for working, hammocks for relaxing, and a cool breeze that makes its way through the open-air breezeway. A few tents overhead provide shade and protection from the rain.

There is a library full of books that you can read while in the lobby, or you can “leave one and take one.” Books are available in just about every language. This is also where the office of the Harbor Master is located as well as access to the marina maintenance crew.

But most important, this is where all the sailors hang out to get relief from the heat and of course, to talk with other sailors. There is always upbeat music playing, which we have trained ourselves to tune out while working.

There are a couple of stray cats and one kitten that has been adopted by all the sailors and marina crew. These cats drive Cap’n Jack and Scout crazy. We generally bring the Seadogs with us into the lobby every day while we work so that they also can get a break from the extreme heat.

We met another cool sailing couple, Mer and Dan. Mer is French, and Dan is British. They have been in Brazil for three months and head toward French Guiana next. They are young, not sure their exact age, but I would guess mid-to-late 20s. They have an apartment in London that they rent out for what they call a “ridiculously obscene price” and use the money they make from the rental to support their cruising kitty. They have no other source of income, so they always stay at anchor, never eat out (only cook on the boat), and do 100% of their boat maintenance themselves. I still find it fascinating that if you want to sail the world, you can find a way financially.

At dinner that evening, Maik and I talked about how on land our international relationship seems completely crazy. How ridiculous it seems to have a relationship with one person who lives in the US and the other who lives in Germany. People have asked us for the past six years how we manage this, and it isn’t easy. I wouldn’t recommend this kind of long-distance relationship, although we found a way to make it work all these years. But at sea, it’s completely normal and common for relationships to exist without borders. And no one we meet in these many ports seems at all surprised when we tell them I am from America and Maik is from Germany. In fact, it’s rare to find couples cruising together who are from the same country.

Tuesday, 19 March 2019

We had a lazy bag made by Christoph that we were set to install on this day. It was Maik’s turn to strap on the bosun chair and make the climb up the main mast to the top of the crow’s nest to install the rigging.

A lazy bag is a device designed to wrap itself around the main sail with lines attached to the mast spreader, creating a bag to capture the main sail when the halyard is released. The sail drops right into the bag. In addition to looking really nice and clean and organized, this is a safety feature when we are at sea. We no longer will have to fight the sail that may be flapping in heavy conditions when we try to bring it down, nor will we have to hand tie it on the foredeck. The sail will simply drop into the bag, the sail will be contained, and then we zip up the bag when conditions allow.

Wednesday, 20 March 2019

We said goodbye, for now, to Robin and Philemon, who headed to Europe by plane for a month. They were so sweet and baked us homemade bread before they left.

That afternoon, I interviewed Emeline for one of the international pumping magazines for which I often contribute articles. She is a female engineer who sails six months of the year, and then works on an offshore rig the other six months of the year. She is among the 1% of female engineers for her company. She is at sea even when she and Felix are not sailing the world in their little monohull, Sea You. It’s a fascinating story that I will post for you once it’s published.

I spent the rest of the week making a list of supplies to find while in Alabama and preparing for my trip to our land home.

BACK IN THE GOOD OLE USA (March 24 – April 8, 2019)

I had not been back in Alabama since Thanksgiving, and I had not been to our apartment in Gulf Shores since I left with the pups to fly to Germany on July 30, 2018. Seven months is a long time to be away from home.

I had an early flight from Recife, which meant I needed to leave the marina at 04:30 with our taxi driver/friend Marco to make the 2-hour drive to the airport.

It felt strange being on an airplane. The 8-hour flight was ok, but I had a 14-hour layover in Orlando. It was an overnight layover, so I decided to take a cheap hotel near the airport and sleep during the layover. This made the 1.5-hour flight to Pensacola the next day manageable and helped me quickly shake any jet lag.

My dear friend, Michele, picked me up from the airport. I planned to stay two nights with her and Doug while we had renters in our apartment in Gulf Shores. Maik had given me a long list of boat supplies to find while in the states that we couldn’t get in Brazil. Michele and I went on the hunt at WalMart and Lowe’s. Oh, how I have missed these great American super stores!

We filled her car with supplies and headed back to her house for a barbecue with more friends — Steve, Catherine, Jenny, Fritz, and of course, Doug (Michele’s boyfriend). We had a blast catching up! It’s so great to see my American friends again!

I made it to Gulf Shores on Monday morning and struggled a bit to settle in. It didn’t feel like home without Maik and the pups, but I immediately got busy on several projects after visiting with more friends—Trisha, Krista, and Tom.

One of my main tasks for the trip was to try to sell enough things in my offsite storage unit to move to a smaller, cheaper storage unit. I was able to easily sell tons of old furniture items on Facebook Marketplace and brought a few things back to the apartment to use there. During the two weeks stateside, I was able to accomplish moving from a 10 x 10 storage unit to a 5 x 10 unit, cutting my footprint and the monthly payment in half. I was able to use the money gained from the furniture sales for all the boat supplies I needed to purchase.

Meanwhile, I also sold my car to my friend Trisha—my cool VW Beetle Convertible. I love this car, but it’s just sitting there all these months, so now I can save money on the payments and insurance. It was a huge expense each month, so this is a relief to be free of that. We still have our old beat-up Jimmy truck that we can drive while in Gulf Shores, and this is all we really need. We barely need one car right now, and we definitely don’t need two!

I struggled to find a good rhythm at home—especially at first. I was enjoying the long, hot showers and the unlimited supply of ICE, but I found it hard to concentrate on real work. I thought I would love being in the civilized world so much that maybe I wouldn’t want to return to Brazil, but this only made me want to get back to the boat more. I continued to realize that some of the creature comforts I always thought I couldn’t live without are just not that important to me anymore.

As the famous sailor, Robin Lee Graham, once said, “At sea, I learned how little a person needs, not how much.”

My amazing son, Bo, came to visit me for the weekend. It was fantastic to have some very high-quality one-on-one time with him. I miss my kids so much and this is the hardest part of being at sea!

Bo and I spent the weekend talking, catching up, and watching all the Oscar-nominated movies. This is our tradition. We do it every year and come up with our own opinions of who should have won the Academy Awards. We highly recommend BlackkKlansman and Green Book. They were our favorites over the weekend, but we also liked The Wife and The Favourite.

We also spent some time over the weekend cheering on our Auburn Tigers with our neighbors, Tom and Krista! Our team made it to the NCAA Final Four Basketball Tournament for the first time in history, but lost in the first round. It was cool to share the experience with other loyal Auburn fans and friends! War Eagle!!!!

During my second week home I got to spend a lovely dinner with friends/neighbors, Lynn and Mike, and then got a visit from my sis-in-law, Pam, and my niece, Allie, who drove all the way from Decatur to visit me for a couple days. We went to the beach and had a fabulous time together. We also went to Mobile and had dinner with my other sis-in-law, Dana, and my niece, Ashton, and nephew, Wells, at their restaurant, The Dumbwaiter.

It was fabulous seeing family, but I was devastated to not be able to spend any time with my parents or with my precious daughter, Shelby.

Time in Gulf Shores was productive and went by so fast. I loaded up three huge suitcases full of supplies for the boat, then headed back to Pensacola for another fun evening with Michele and Doug, and our friend, Shirley.

After an early flight out of Pensacola, I had another long layover in Orlando. This time it was 10.5 hours and during the day rather than overnight. I stayed at the airport and caught up on all the work I didn’t get done during my hometown visit.

BACK IN BRAZIL (April 9 – 14, 2019)

While I was in the U.S., Maik had moved Seefalke onto dry dock in the Marina Jacaré Village shipyard and had been extremely busy with repairs and upgrades.

As Marco drove me into the marina, I didn’t even recognize Seefalke. Her bright orange paint had been almost completely stripped from her hull and there were little bits of orange paint peelings all over the dirt ground in the shipyard.

Maik and the pups had gotten used to living on dry dock since the day after I left for the U.S., and I learned quickly what it’s like to live in a sailboat on dry land.

We have access to electricity and water, but we can’t use the head at all. There is a bathroom in the marina lobby, which is just a short walk from the shipyard, but it’s a major project to get in and out of the boat.

We have a swimming ladder attached to the back of the stern, but it’s not long enough to reach the ground while Seefalke is sitting on dry land. We have another traditional ladder leaned against Seefalke’s stern. We climb a few steps on the regular ladder, then switch to the swimming ladder to climb the rest of the way to the top. On the way down, we use the swimming ladder then can switch to the regular ladder. We also have a huge oil can we can step onto on the way down. This system works, but it is especially inconvenient when I need to go to the potty in the middle of the night. But this is our situation at the moment.

As I mentioned earlier, living on dry dock is like living in a tree house!

Then, there is the issue of getting the Seadogs on and off the boat. Seefalke’s deck is about 3 meters (10 feet) off the ground. It would not be safe to try and carry Cap’n Jack and Scout up and down the ladder.

Maik used his engineering and seamanship skills to engineer a puppy crane for them. We strap them in their extraordinarily safe life vests, which have two handles on the top. Safety straps with D-rings connect the life vest handles to a line that is rigged with a block to the mizzen boom. Then we can simply lower them or raise them safely and securely with the well-designed puppy crane. They don’t seem to mind. Their tails are wagging the whole way. We posted a very cool video of this system for our Patrons. You can join our crew on Patreon for as little as $2 per month to get extra features like this.

ONGOING REPAIR AND UPGRADE PROJECTS

Paint Job

The paint job project is ongoing. At this point, we have scraped all the paint, sanded, and began the priming stages. Removing the paint is not as easy as it sounds as our ship had four decades of paint layers. Heavy rain delayed the project several days and continues to extend it. Seefalke still needs several layers of primer, with sanding in between each layer, and then the bright orange paint.

Maik considered painting Seefalke a different color as he has never really loved the bright orange facade, but I wouldn’t let him. Her orange color is part of her character and personality. She was meant to be ORANGE!

After all that is finished, we will apply the coppercoat antifouling on Seefalke’s bottom and then give that coating a harsh sanding before putting her back in the water.

Fuel Leak