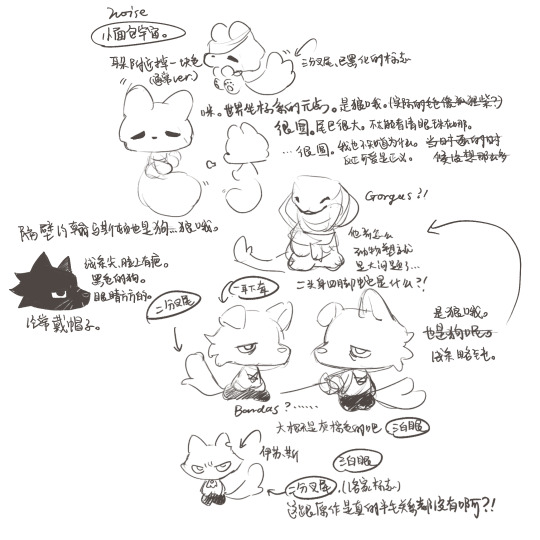

#gorgas/bardas

Text

Round 1, Match 4

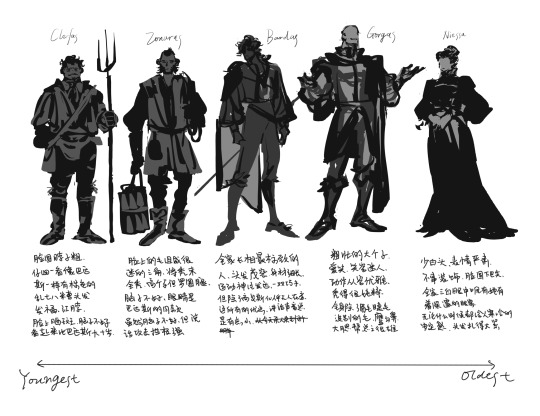

Blitzø and Barbie Wire (Helluva Boss) vs Bardas and Gorgas Loredan (The Fencer Trilogy)

Propaganda under break

Blitzø and Barbie Wire

Blitzø accidentally killed their mom and sent Barbie into addiction, she never wants to see them again but he keeps trying to talk to her

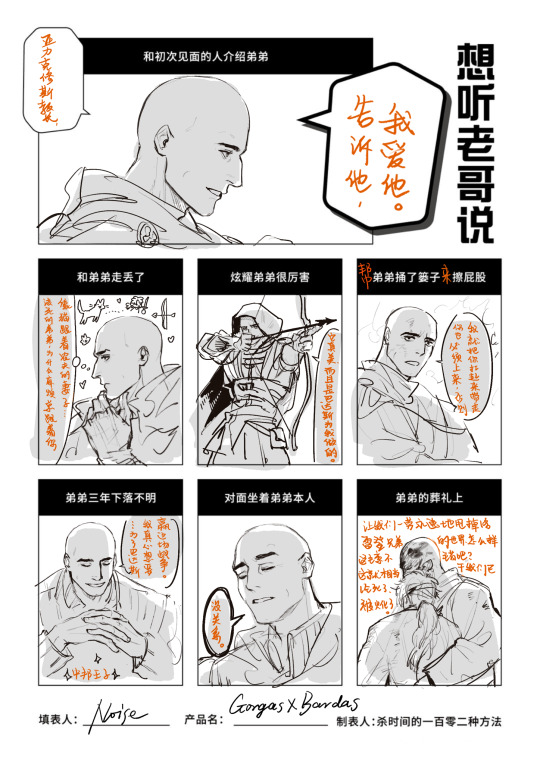

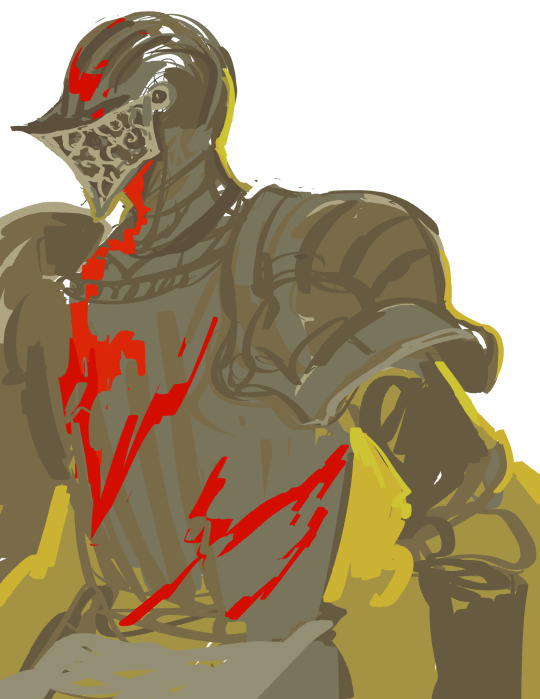

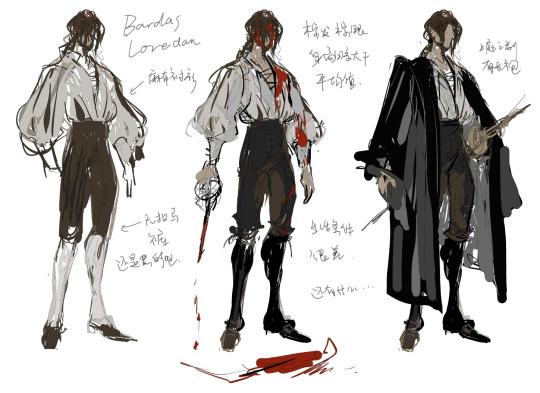

Bardas and Gorgas Loredan

Bardas killed Gorgas's kid as revenge. Then turned his body into a bow and gave it to Gorgas to hunt with without telling him what it was made of.

#worst siblings tournament#Round 1#Poll#Helluva Boss#The Fencer Trilogy#Blitzo#Barbie Wire#Unhappy Campers#Bardas Loredan#Gorgas Loredan#poll tournament

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

this post springs from Thoughts On Sincerity In SFF, but:

In the oeuvre of K.J. Parker, everyone's a terrible person, definitely on the outside, and many of them on the inside, but Parker/Holt or his fictional universe or both has a sort of baseline goodness.

A lot of Parker is about perversion of goodness – how the most fucked up moment in The Belly of the Bow isn't Bardas Loredan making a bow out of his nephew but Bardas' brother, the boy's father, forgiving him for the sake of family; how Poldarn's desire to know, like Oedipus's, destroys him and a bunch of other people; or how Temrai's adherence to tradition gets literally everyone killed.

(Also I had forgotten that Gorgas Loredan opens the gates of Peridameia so that Bardas can be a hero, which is very yikes.)

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

No Exit from Fantasyland

by Alasdair Czyrnyj

Monday, 22 February 2010Alasdair tries to come to grips with the Fencer Trilogy~

Before I begin, I have a confession. Up until a few years ago, I had never read anything of that great amorphous genre of fantasy. It was a matter of bad timing, really. I spent most of the pre-teenage years most sensible people spend reading children's fantasy reading Star Trek tie-ins, and the years after that saw me shifting through classic science fiction and history in rapid succession. By the time I started to get serious about revisiting fantasy I'd hit university, meaning that my choice of fantasy has tended to fall in line with my other literary interests. When people talk of fantasy, my mind hearkens to the glacial machinescapes of Ian R. MacLeod, the Marxist surrealism of China Miéville, the savage deconstructions of Michael Swanwick, the humanist comedy of Terry Pratchett, even the bureaucratic terror of Franz Kafka.

And K. J. Parker.

K. J. Parker is something of an odd duck. She's been writing for over a decade now, though she's only gained any recognition in the last couple of years. Her output tends to be fairly modest; normally a new book a year, with no short stories or other external writing. We don't even know who she is; "K. J. Parker" is a pseudonym, and about the only things anyone knows about her is that she's a woman, she hails from a farming family in Vermont, she likes history and skilled trades, and she's married to a solicitor in southern England.

So, what it is about Parker's work that merits serious critical attention? What would compel me, a reader who normally avoids trilogies like grim death, to work my way through her entire bibliography in the space of a year?

In short, it is because she writes fantasy the way no one else does. And it is

horrifying

.

Here, I'll explain what I mean.

Colours in the Steel, or How to Besiege a Late-Medieval Metropolis in One Easy Lesson

Parker's first work, the Fencer Trilogy, has something of a misleading format. While there are three books that describe the journey of a particular group of characters, it doesn't really

read

as a trilogy. Each book is set in a completely different location from its predecessors, and each is separated from the previous book by an interval of several years. The books also ignore the classic conventions of genre by redefining the relationship the characters have with their world. Rather than commanding their narratives and acting as the centers of the universe, the characters of the

Fencer

books are forever bound to the material and economic forces that drive their world, where success is determined by a comprehension of these forces which, due to human nature, can never be total.

To understand this world, we are given the mopey (if initially sympathetic) character of Bardas Loredan, ex-farmer, ex-soldier, fencer, bowyer, and occasional general as a guide. We meet Bardas in

Colours in the Steel

(1998), working as duelist at law (a profession, surprisingly enough, that Parker renders as plausible, or at least as logically illogical) in the Constantinople-flavored Triple City of Perimadeia. Like all great cities, Perimadeia has its enemies, chief among them Temrai, leader of the plainspeople whom Perimadeia has traditionally dealt with through the time-honored strategy of butcher-and-bolt. A modernizer in the style of Peter the Great, Temrai has traveled incognito to Perimadeia to school himself in the construction of heavy machinery, so that his people may devise the weapons they need to bring down the Triple City once and for all.

While this sounds like a fairly generic setup for a fantasy novel, Parker's prose gives the story a unique bent. While most authors would bring their worlds to life through architectural tours and history lessons, Parker builds her world with machinery. Through all three books, great care is lavished on the step-by-step forging and assembly of material goods. In the course of reading the

Fencer

books, a reader will learn how to forge a sword, how a water wheel works, how to assemble a trebuchet, how to assemble a bow, and how to subject armor to destructive testing. While this would normally read as mere authorial self-indulgence, it is a credit to Parker that these passages serve to drive the story. After reading page after page of construction, the reader begins to reinterpret the story appropriately, reading the plot not as a simple clash of personalities, but as a conflict between great, grinding forces made up of millions of people, animated by a single goal, and fueled by the prosaic things we take for granted in our world. Rather than magic or the feudal privilege, Parker's world operates by economics, political struggle, logistics, and, ultimately, by conflict. While Perimadeian culture is kept somewhat murky, by watching how its inhabitants use and interpret their machines, we see how Perimadeia operates and how its citizens interpret the world.

This is not to say that there is no magic in the books. Indeed, one of the main plotlines of the trilogy concerns the operation of magic. Early on in

Colours,

a young woman approaches Patriarch Alexius, the chief lecturer at Perimadeia's magical college, asking that he place a curse on Bardas Loredan to punish him for his role in "murdering" her uncle during a duel. After applying the curse, Alexius spends the rest of the story trying to undo it, revealing a hidden truth about magic:

no one knows how it works

. Despite studying it for decades, Alexius does not understand anything about its operation, as he freely admits. Even Parker's description is hard to puzzle out; it appears to operate on a sort of system of universal balance dubbed "The Principle," and it can be used to alter key decisions through precognitive visions, though it's never made clear if the visions are prophecies or simply hallucinations. Oh, and they might be manipulated by someone none of the characters know about.

The book builds slowly for the first half, with Bardas drifting from job to job, Alexius trying to figure out just what he did, and Temrai transforming his nation into a mechanically-competent band of semi-settled tribespeople. At the halfway mark, Temrai's people approach the gates of Perimadeia, and a great siege begins. The depiction of the siege is one of the high points of the novel, and one of the areas where Parker's writing shines. The whole enterprise is gloriously messy. There's uncomprehending denial on the part of the Perimadeians, skirmishes that devolve into rugby scrums, artillery duels that don't accomplish much, illogical politics, and even a decent secret weapon. Despite his dislike of the military life, Bardas is conscripted into the defense of Perimadeia, managing to fight the plainspeople to a draw.

At this point, the book explodes.

Throughout the book, there are references to an unnamed bald, bearded figure who seems to have a hand in every major development of the book, acting as an advisor to Temrai and haunting Alexius' visions. In the final hundred pages of the book, a name is finally put to the face: Gorgas Loredan, estranged brother to Bardas. However, as he explains to Alexius in a somewhat out-of-place monologue, his motives are simple. It turns out that years ago, he, Bardas, and the rest of their family were all living on the farm off on the island of Mesoge. However, after an unfortunate incident in which Gorgas pimped out his older sister to two visiting noblemen, only to kill them, his sister (failed), his father, and Bardas (failed again) when the latter two caught them in the act, Gorgas fled home, while Bardas left later to join the Perimadeian army. However, what's past is prologue, and all he wants to do is reconcile with his brother.

Then he opens the gates of the city.

It's shocking. It's totally unexpected. It seems like Parker is cheating. At yet, as the city falls and the cast flees, it doesn't seem like a cheat. Perhaps there's more going on than meets the eye. Maybe the next book will have some answers.

The Belly of the Bow, or Bank Vs. University: Blood on the Ledger

As

The Belly of the Bow

(1999) opens, there is a bit of a shock. Two years have passed between books. The action has shifted to the environs of the late city of Perimadeia, specifically to the island of Scona, the peninsula of Shastel, and an island-based trading community know as "the Island." Fortunately, most of the characters from the first book have escaped the fall of their city to make new lives for themselves.

Once again, war dominates the novel, but it is a rather odd type of war. The cause, it seems, is philanthropy. Some time ago, a great charity and center of learning based with the august title of "The Grand Foundation of Charity and Contemplation" started a homestead program in Shastel that, due to a misunderstanding of basic economics, ended up creating a peninsula of indentured peasants. After a civil war or two, the Foundation became a regional political player, only to be undercut by a new bank on the island of Scona, which buys out tenant farmers and offers loans at less ruinous interest rates. However, since this is the days before the World Trade Organization, the two groups are forced to resolve their differences in the only civilized way: by cross-border raids against recalcitrant debtors.

The bank, incidentally, is named the Loredan Bank, after its founder, Director Niessa Loredan, and with sergeant-at-arms Gorgas Loreadan handling the management of the day-to-day bloodshed.

While

Belly of the Bow

departs from the setting of the previous book, it uses the opportunity to examine the dynamics of the Loredan family. In a genre that has gleefully abused the concept of rape for the purposes of titillation or for ill-advised stabs at profundity, Niessa Loredan is a welcome change of pace. In the years after her experience (and her hounding out of the family at the hands of Bardas and her other brothers), Niessa has remolded herself into a vicious utilitarian, focused solely on securing her bank's future. It is through Niessa that magic makes a return to the story, becoming in her hands an instrument in which the will can directly manipulate the future, with no consequences worth considering. (Alexius is conscripted by Niessa into this precognitive war effort, with the result being a sort of magical war between the two polities that may or may not be affecting the actual war.) Overall, while a functional human being, Niessa still endures her past, neither capable nor all that interested in escaping it.

Bardas, meanwhile, continues to wander. He spends most of the book setting himself up as a bowyer (i.e. Guy Who Makes The Bows Archers Use) in a secluded hut on Scona, quietly pretending that his livelihood isn't dependent on his siblings' charity. After that illusion proves impossible to sustain, he escapes and returns to the family farm in the Mesoge, to the two brothers who never left. What follows is a rather heartrending sequence, as the three attack each other with waves of mutual recrimination and deflected self-loathing. In the end, Bardas is spirited back to Scona, a man with no home.

The real driving force in

The Belly of the Bow

however, is Gorgas. In the initial pages, Gorgas appears as having truly reformed, becoming a beloved general and a family man to boot. However, there is something off about his character. Gorgas routinely moves heaven and earth for Niessa and Bardas, despite the indifference of the former and the outright hostility of the latter, while remaining curiously detached from his own family. Indeed, as the book progresses, Gorgas becomes a terrifying figure, not so much for his actions but for his outlook on the world. For Gorgas, the entire point of his life is to make restitution for his crime and reunite his family. Unfortunately, that's the only purpose to his life. For Gorgas, opening the city gates for an enemy army or assassinating complete strangers or riling an island into a futile rebellion is justified, for it is always the Loredans against the world. What's past is in the past, but family is forever, even if the family no longer exists.

As the Loredan family disintegrates, the greater gears of war and money grind on. The war between Scona and Shastel continues. Scona wins a great victory against a Shastel raiding party, dooming itself to eventual defeat at the hands of the Foundation. Scona is invaded. Battles repeat themselves. Meanwhile, Bardas discovers Gorgas' role in the fall of Perimadeia and his twin motivations (wipe out the Loredan Bank's bad debts, and get Bardas back with the family), and proceeds to do something so horrific that it will forever destroy Gorgas' love for him. It doesn't work. The book closes as the first did, with the main cast fleeing the fall of Scona across the waves.

The Proof House, or Things Are Smashed Apart

Just as the appearance of Gorgas drastically altered the end of

Colours in the Steel

, so too does

The Proof House

(2000) drastically alter the course of the

Fencer

story with the introduction of the Empire. This great polity was never mentioned in the previous two books, apparently being landlocked out of sight and out of mind. However, with the fall of the city of Ap'Escatoy (a joyful accident care of Bardas Loredan, working the saps for three years since the end of the last book), the Empire now has a western coastline.

In many ways,

The Proof House

is the grimmest of the three books. The tale it tells is one of imperial conquest and consolidation. In the previous book, much care was lavished on the depiction of the various societies that inhabit the waters around Perimadeia: the bibliophile factionalists of Shastel, the easy-going disorder of Scona, the frivolous horse-trading Islanders, even the backwater dullards of the Mesoge. However, in

The Proof House

, it's suddenly revealed that this great, varied world exist in a space no bigger than the Aegean, and that it is all fated to be consumed by a great foreign power, not out of malice, but just because imperial expansion is what they do, and that's that.

This process of absorption and assimilation is illuminated through two main plotlines. After spending his new promotion at useless assignment at an imperial proof-house (a place where plate armor is made and tested to destruction), Bardas is given honorary command over an Imperial army sent to drive Temrai's semi-settled people out of the old Perimadeian hinterland. After the Imperial commander is killed, Bardas takes command, returning, for a while, to the one place where his skills were put to constructive use. The second plot thread concerns the fate of the Island at the hands of the Empire. The whole affair starts out as a sort of comedy, with the merchants of the Island essentially selling the Empire a fleet, never realizing that the Empire might decide to not give them back. Events soon spiral out of control, and comedy fades to annexation, rebellion, incompetence, and death.

As the center fails, mere anarchy is loosed upon the world. In the early chapters, many of the characters are in magic-based communication with Alexius whom, it is quickly revealed, died between books. Figures seen in the dreamscape grow increasingly blurred, claiming to be students from the future watching a critical turning point in the past. Eventually it appears that the voices are none other than the voice of the Principle itself, which is not so much a force of magic as a metaphysical avatar of entropy itself. As for Gorgas, free of Niessa's control and set up as king of the Mesoge, the time has come to reunite the Loredan clan by every means necessary. By the end of the book, cities have been stormed, beloved secondary characters have been drawn and quartered, the future is nothing but boots on human faces, and Bardas Loredan has, in essence, been condemned to hell.

So, What Is It?

One of the main problems any reader will have the

Fencer

trilogy in trying to fit it into some sort of rubric from which it can be judged. Using the Romantic framework of classic fantasy is out of the question, and "dark" fantasy is more of a marketing contrivance than a useful critical tool. In her 2008 work

Rhetorics of Fantasy

, Farah Mendlesohn described the trilogy as an "immersive fantasy," a fantasy story that (to vastly oversimplify), is set in a coherent self-contained world within which the characters inhabit and critique. For the longest time, I had tended to think of these books (and Parker's work as a whole) as materialist fantasies; stories not set in our world but which obey all of its physical and sociological parameters. All these terms are helpful in describing the

Fencer

books, but they don't really tell the whole story.

In the end, perhaps the best way to look at the

Fencer

trilogy, and K. J. Parker's work as a whole, is as absurdist fantasy. To crudely simplify something I cribbed from Wikipedia, absurdism is a branch of existentialism which holds that the universe does not hold any fundamental meaning pertaining to the individual, though individuals can construct their own meanings if they so choose. For the characters in the

Fencer

trilogy, life is deeply absurd. Their world is one bound by great impersonal material forces with individuals can only influence intermittently, assuming they even recognize what those forces and when those critical turning points occur. There are no deities, literal or otherwise; aside from the plainspeople, the peoples of the

Fencer

books are overwhelming atheistic. Furthermore, because the world is bound by material systems of infinite number and complexity, there is no safe haven. Everyone's action affects someone else, with the end result being that the vast majority of mankind is nothing but grist for the mill of history. Even when decisions are made, they are often made by people who are under the grip of some illogical idea, or who simply don't understand the implications of their choices. This point is driven home in the second book, where an argument over a reprisal against Scona swells from a small reprisal raid to an invasion on the scale of Operation Barbarossa all so one faction of the Shastel elite can one-up the other. It's hilarious and horrible at the same time.

The

Fencer

Trilogy does not make sense. Intentionally. And that is why it is brilliant.

Is It Worth It?

Compared to Parker's later books, the

Fencer

trilogy is very much a first work. While the description is evocative, the sudden twists are suitably shocking, and the jokes are funny (Yes, there are jokes. Can't have an absurdist novel without a good joke or two.), the books do have a uneven feel to them, as if too many ideas are being assembled into a framework that can't quite hold them. While the characters are interesting and sympathetic, at times they seem to be reduced to mere viewpoints, rather than being individuals caught in the grip of great external forces. There is also far more "down time" than in Parker's other books, with scenes just designed to just worldbuild rather than worldbuild and drive the story. In the end, while I would recommend it, I would suggest that newcomers to Parker start with the later

Engineer

Trilogy, which covers many of the same themes with a far more efficient mechanism.

Also, after you finish the

Fencer

Trilogy, you may feel the need to drown yourself in a nearby lake. This is normal. Just wait a few hours and it will pass.

Oh, and:

Fantasy Rape Watch

Women raped: 1

Women mind-raped: 1, maybe

Number of women who suffer from their experiences: 1 (it's hard to tell just what happened with that second one. 'Course, that's probably the point.)

Themes:

Fantasy Rape Watch

,

Books

,

Sci-fi / Fantasy

~

bookmark this with - facebook - delicious - digg - stumbleupon - reddit

~Comments (

go to latest

)

Arthur B

at 17:28 on 2010-02-22This review is awesome, but I'm wondering whether Parker's philosophy is as unique in fantasy as you imply. The

Vlad Taltos

series by Steve Brust has always had a good line in the sort of materialism/absurdism and social/economic critique you talk about here. There's some bits of Erikson's Malazan series which seem informed by a "no meaning but what we impose ourselves" philosophy, and Jack Vance's books are almost all characterised by peculiar social constructs, raw economics and greed, and the necessity of people to find their own way in a world that doesn't make sense to them.

I will be looking into the

Engineer

trilogy though, if you feel it's genuinely better than the

Fencer

books. Does it need much knowledge of the earlier series to fully appreciate?

permalink

-

go to top

Andy G

at 20:43 on 2010-02-22Dare I also mention Ursula le Guin again? ;)

permalink

-

go to top

Arthur B

at 23:01 on 2010-02-22LeGuin is always worth a mention...

permalink

-

go to top

Alasdair Czyrnyj

at 00:02 on 2010-02-23Well, as I said Arthur, I'm still feeling my way around the fantasy genre (hell, I read literary criticism, for cripes sake), so my idea of "generic fantasy" is still a collection of broad stereotypes I've picked up from people bitching on the Internet. Still, I would say that Parker has a gift for taking those elements you mentioned above and making them as these great, terrible things that will consume all in the end.

As for which books to start, I'm biased towards the

Engineer

books because they're the ones I started with, and they're the ones I had the easiest time trying to figure out (Having a decent amount of sustained online criticism helped a bit too). Fortunately, all of her trilogies and her recent singletons are set in completely seperate worlds, so there's no risk of missing anything wherever you start.

Still, I would recommed waiting before you get to her

Scavenger

books. They're one of those trilogies you have to read twice just to figure out what the heck was going on.

permalink

-

go to top

Wardog

at 09:18 on 2010-02-23I read The Colours in the Steel and quite liked it ... but I had really trouble shifting from that to The Belly of the Bow. I think it was more a question of my expectations than the books though - this article inspires me to revisit and re-evaluate.

permalink

-

go to top

Alasdair Czyrnyj

at 21:06 on 2010-08-08Random K. J. Parker news!

If there's anyone out there who wants to sample her writing, she recently did a short story for Subterranean Press' seasonal magazine, which they have thoughtfully posted on their website.

http://subterraneanpress.com/index.php/magazine/summer-2010/fiction-amor-vincit-omnia-by-k-j-parker/

She's also got another short story out in a sword and sorcery anthology,

of all things

, and

a new book

coming out next winter.

0 notes

Text

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

#bardas loredan#fencer trilogy#kj parker novel#yes i made it up#kj parker#colours in the steel#the belly of the bow#the proof house#gorgas Loredan

56 notes

·

View notes

Text

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

With submissions about to close, I'm going through the pictures for each of them. Most have links to images, or I've been able to find some official or fan art, but there's a few I haven't been able to track down. If you can find any, send it as a DM or ask, otherwise I'll have to use book covers or series logos for them

Belzedar, from The Belgariad

Torak, from The Belgariad (I've got a book cover with him but it's kind of low res)

Bardas and Gorgas Loredan, from The Fencer Trilogy

Helen and Richard Gansey, from The Raven Cycle

If it's fan art, I'd like to know that the artist is OK with their work being used here.

#worst siblings tournament#update#the belgariad#Belgariad#belzedar#torak#Bardas Loredan#Gorgas Loredan#The Fencer Trilogy#Helen Gansey#Richard Gansey#The Raven Cycle

1 note

·

View note

Text

Round 1

Skystar and Graywing (Warrior Cats) vs Sasuke and Itachi Uchiha (Naruto)

Scar and Mufasa (The Lion King) vs Jude and Taryn Duarte (The Folk of the Air)

Krauss, Eva, Rudolf and Rosa Ushiromiya (Umineko) vs The Princes of Stormhold (Stardust)

Blitzø and Barbie Wire (Helluva Boss) vs Bardas and Gorgas Lordan (The Fencer Trilogy)

Vinsmoke Ichiji, Niji, and Yonji (One Piece) vs Nikolai and Vasily Lantsov (Grishaverse/Shadow and Bone)

The Batsiblings (Batman) vs Rattlesnake and Sirocco (Wings of Fire)

Dee and Dennis Reynolds (It's Always Sunny In Philadelphia) vs Folgers Coffee Siblings (Folgers Coffee commercial)

Ianthe and Coronabeth Tridentarius (The Locked Tomb) vs Therese and Jeanette Voerman (Vampire: The Masquerade - Bloodlines)

Junko Enoshima and Mukuro Ikusaba (Danganronpa) vs Queen Elizabeth and Queen Mary (English history)

Ruby and Aquamarine Hoshino (Oshi no Ko) vs Richard and Helen Gansey (The Raven Cycle)

The Endless (Sandman) vs Lark and Sparrow Oak-Garcia (Dungeons and Daddies)

The Bridgerton siblings (Bridgerton) vs Clary Fairchild and Sebastian Morgenstern (The Shadowhunter Chronicles)

The Sanderson Sisters (Hocus Pocus) vs Velvet and Veneer (Trolls 3)

The Seven Sisters Colleges (Real Life) vs Zeus and Hera (Greek mythology)

Akio Ootori and Anthy Himemiya (Revolutionary Girl Utena) vs Tom and Jake Berenson (Animorphs)

The Hargreeves siblings (Umbrella Academy) vs Ledroptha Curtain (The Mysterious Benedict Society)

Jiang Cheng and Wei Wuxian (MDZS/The Untamed) vs Rei Asaka and Fukiko Ichinomiya (Oniisama E)

Adam and Eve (NieR: Automata) vs Dys and Tangent (I Was A Teenage Exocolonist)

Percy Jackson and Polyphemus (Percy Jackson) vs Mercer and Gage (The Silt Verses)

King Richard and Prince John (Robin Hood/English history) vs Cleopatra VII and Ptolemy XIII (Egyptian history)

Uru Somezuki and Saito Sejima (AI: The Somnium Files) vs Illumi, Killua and Alluka Zoldyck (Hunter x Hunter)

Andrew and Ashley Graves (The Coffin of Andy and Leyley) vs Belzedar (The Belgariad)

Cersei, Jaime, and Tyrion Lannister (A Song of Ice and Fire) vs Torak (The Belgariad)

Phillip and Caleb Wittebane (Owl House) vs Ogata Hyakunosuke and Hanazawa Yuusaku (Golden Kamuy)

Ruffnut and Tuffnut Thorston (How To Train Your Dragon) vs Andrew and Aaron Minyard (All for the Game)

Goneril and Regan (King Lear) vs Ruby Rocks and Saccharina Frostwhip (Dimension 20: A Crown of Candy)

The Beagle Boys (Donald Duck universe) vs Catherine and Hindley Earnshaw (Limbus Company)

Sam and Dean Winchester (Supernatural) vs John Wilkes and Edwin Booth (US history)

Anne and Mary Boleyn (English history) vs Rodrick, Greg, and Manny Heffly (Diary of a Wimpy Kid)

Anastasia, Drizella, and Cinderella (Cinderella) vs Wolf 40f and Wolf 42f "Cinderella" (Real Life, Druid Peak wolf pack)

Byes: Azula and Zuko (Avatar: The Last Airbender), Cain and Abel (The Bible)

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

These are the siblings that have been submitted. This isn't the final order, I'm going to randomize the seeds but the most submitted siblings are getting high seeds, so they don't knock each other out in the first few rounds

Azula and Zuko - 5 submissions

Cain and Abel - 4 submissions

Cersei, Jaime, and Tyrion Lannister - 4 submissions

Ianthe and Coronabeth Tridentarius - 3 submissions

Akio Ootori and Anthy Himemiya - 2 submissions

Anastasia & Drizella and Cinderella - 2 submissions

Andrew and Ashley Graves - 2 submissions

Adam and Eve (Nier Automata)

Andrew and Aaron Minyard

Anthony, Benedict, Colin, Daphne, Eloise, Francesca, Gregory, and Hyacinth Bridgerton

Bardas and Gorgas Loredan

Belzedar

Blitzø and Barbie Wire

Catherine and Hindley Earnshaw

Clary Fairchild and Sebastian Morgenstern

Clear Sky(Skystar) and Graywing

Cleopatra VII and Ptolemy XIII

Dennis and Dee Reynolds

Dys and Tangent

Folgers Coffee siblings

Goneril and Regan

Helen and Richard Gansey

Jiang Cheng and Wei Wuxian

Johns Wilkes and Edwin Booth

Jude and Taryn Duarte

Junko Enoshima and Mukuro Ikusaba

Killua, Illumi and Alluka Zoldyck

Lark and Sparrow Oak-Garcia

Ledroptha Curtain

Mary and Anne Boleyn

Mercer and Gage

Nikolai and Vasily Lantsov

Ogata Hyakunosuke and Hanazawa Yuusaku

Percy Jackson and Polyphemus

Phillip and Caleb Whittebane

Prince John andKing Richard

Queen Mary and Queen Elizabeth

Rattlesnake and Sirocco

Rei Asaka and Fukiko Ichinomiya

Rodrick, Greg, and Manny Heffly

Ruby and Aquamarine Hoshino

Ruby Rocks and Saccharina Frostwhip

Ruffnut and Tuffnut Thorston

Sam and Dean Winchester

Sasuke and Itachi

Scar and Mufasa

Seven Sisters Colleges

The Batsiblings - Dick Grayson, Jason Todd, Tim Drake, Damian Wayne, Cassandra Cain, and Duke Thomas

The Beagle Boys

The Endless - Destiny, Death, Dream, Destruction, Desire, Despair, & Delerium

The Hargreeves Siblings

The Princes of Stormhold

The Sanderson Sisters

The Ushiromiya Siblings

Therese and Jeanette Voerman

Tom and Jake Berenson

Torak

Uru Somezuki and Saito Sejima

Velvet and Veneer

Vinsmoke Ichiji, Niji, and Yonji

Wolf 40f and Wolf 42f "Cinderella"

Zeus and Hera

6 notes

·

View notes