#good omens fanalysis

Text

My Favorite Good Omens Moment:

An Essay on Why It Is Cool and Rad

(Part 1)

There's this moment in Good Omens that makes me cackle every time I see it and leaves me full of warmth, so here's an essay on its context and meaning, because explication and analysis are how I show love. I will try to keep my thoughts as tight as possible, but they do have a tendency to spiral outwards, and I am very stoned. Come, sistren, and get nerdy with me.

My favorite moment in the series so far occurs in 1601. To approach it we will first need an assload of context. There's a TL;DR in bold at the end of the Context if you don't fancy reading the whole assload. Key arguments are in italics and bold throughout.

David Tennant gives Crowley a very consistent facial expression every time Aziraphale says something so outlandish Crowley can't quite believe he's hearing it. It's this one:

Chronologically, we see the Eyebrows of Disbelief twice before my fave moment in 1601: once (above left) in that scene on the Garden Wall that familiarizes the audience with Crowley's face before adding the dark glasses, when Aziraphale admits he's given away his sword; once when Aziraphale tells Bildad the Shuhite that he, Aziraphale, has Fallen because he lied to the angels to save Job's children.

The Eyebows of Disbelief always signal surprise and amusement with something Aziraphale has said or done. This amusement is sometimes at Aziraphale's expense and sometimes not.

In the gifs above, Crowley is laughing because what Aziraphale has just admitted to doing is fantastic and unexpected and frankly pretty gd punk rock. He's not laughing at Aziraphale, he's laughing because he is delighted with him. The only record we have thus far of Crowley laughing at Aziraphale is this one:

Crowley laughs when Aziraphale informs him--him, a demon who has personally been through the process of Falling--that Aziraphale is Fallen and must be a demon now. As though of the two of them Aziraphale is the expert on how and under what circumstances this occurs.

And yet when Crowley sees Aziraphale's distress--not his fear of being taken to Hell, but his heartbreak and lostness over the fact that his conscience has diverged from God's stated will--Crowley stops laughing, and instead he acts very kindly towards Aziraphale. He validates the gravity of what Aziraphale has done and assures him he won't turn him in. He sits with him so Aziraphale isn't totally alone (like Crowley probably was) as he goes through the loneliest moments of his existence to that point and picks himself up newly weighted with the secret he must now bear.

And after this scene (in canon as it stands thus far), we don't see Crowley laugh at anything Aziraphale says or does again.

And he really has to work for it sometimes. We talk a lot about the things Michael Sheen is able to convey with his face in Good Omens, and absolutely rightly so; David Tennant earns a chunk of his paycheck in this regard as well. If you haven't given yourself the treat yet, rewatch the scene in Will Goldstone's magic shop in 1941 and focus on Crowley's reactions:

youtube

Tennant takes great care to show, with precision, that Crowley is expending effort not to react to Aziraphale's nervous chaos Muppetry and lack of self-awareness. Crowley is self- and socially and contextually aware enough that he knows (better than Aziraphale, at least, which is not a high bar to clear) what's cringe, what's funny, what's ridiculous, how to behave. But whenever Aziraphale crosses a boundary of normalcy, or even sanity, and there is opportunity to laugh at him, Crowley very carefully doesn't react. He doesn't interrupt him, he doesn't try to correct him, he doesn't make fun of him, he doesn't even smirk; he just watches him, as stone-faced as he can manage, no matter how bizarre Aziraphale becomes.

We should be reading this lack of reaction to Aziraphale's social and rational transgressions as powerful positive action. Go watch the Doctor Who episode "Human Nature," or literally any episode of The Inbetweeners, or read or watch Regeneration, and reflect on what it shows you about English masculinity; then consider again the depth of significance in how English- and male-coded character Crowley treats English- and male-coded character Aziraphale in an England created by an English and male-codedpresenting author based off a book written by himself and another male-presenting author. Within its context of English masculinity, Crowley's lack of reaction is not a neutral stance; it is a very fucking loud show of support.

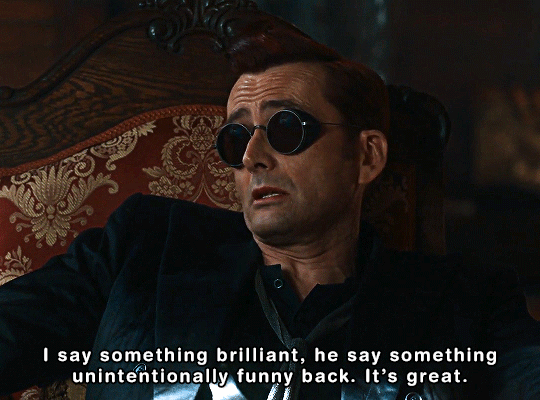

This is not even an inference; it's stated outright in the show. Crowley himself puts it into words 422 years after my favorite moment:

You know how Crowley calls Aziraphale "angel" because the factuality of the descriptor offers him plausible deniability to any Heavenly or Infernal agents who might be listening? Remember how Crowley is a great equivocator? Crowley is equivocating here, too: he's using the cover of what Maggie and Nina will take as a disparaging joke at Aziraphale's expense in order to make a perfectly sincere statement. This is his genuine perception of one of the relationship dynamics he has with Aziraphale and how he feels about that dynamic. Crowley thinks he himself is quite witty (an accurate assessment), Crowley thinks Aziraphale isn't sufficiently self- or contextually aware to hide how strange he is and therefore frequently says and does mad things (also an accurate assessment), and Crowley is Into. That. Shit.

Okay. Now let's look at 1601.

Chronologically it's been almost 1,000 years since we last saw Aziraphale and Crowley. In 537, Aziraphale isn't willing even to consider a labor-saving working arrangement with Crowley of fucking off home out of the damp of Arthurian Wessex; but by 1601, he's worked (and met, and Arranged) with Crowley "dozens of times now," Crowley says, and Azirapahle does not correct him.

In that millienium, Aziraphale has grown to care deeply about Crowley:

In fact he may be somewhat smitten with him:

Seriously, go back and watch Aziraphale here as Crowley approaches and starts speaking to him: he doesn't start smiling until he recognizes that the person speaking to him is Crowley (but he only smiles at Crowley while Crowley's not looking at him).

And Crowley is definitely become smitten with Aziraphale:

Our man(-shaped entity) is so allergic to work he sets up a meeting to weasel, cajole, or (as it happens) cheat a coin toss to get Aziraphale to do an easy temptation for him in Edinburgh, and then in the same conversation agrees to miracle a play into success because Aziraphale gives him a single hopeful look. Crowley's got it bad.

TL;DR: The Eyebrows of Disbelief happen when Crowley is surprised and amused by something Aziraphale has said or done. Sometimes that amusement is delight with Aziraphale; sometimes it is at Aziraphale's expense. Crowley is aware of this distinction, and when his amusement is at Aziraphale's expense, he suppresses it, even when it takes some effort on his own part, and remains stocially composed. This is equivocation on his part: to Celestial/Infernal operatives lacking knowledge of the intricacies of human behavior, this non-reaction would seem like neutrality; to Aziraphale, who shares with Crowley and the audience the contextual knowledge of English masculinity's utter viciousness, this non-reaction is a profound show of support; and in the safety of support from Crowley, Aziraphale lets his weirdness blossom.

As another meta points out [link if I find it again], we also see in Aziraphale's wordless request about Hamlet and Crowley's immediate understanding of it that by 1601 Aziraphale and Crowley have developed an unspoken, coded method of communication with each other.

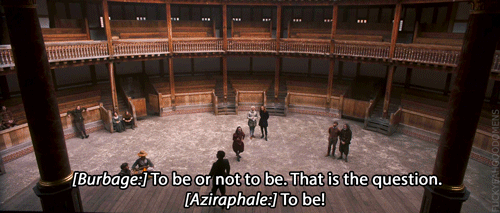

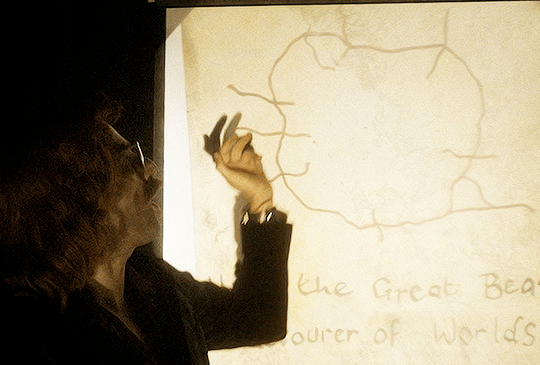

Now that we have all of that in mind, here's my favorite moment in Good Omens:

Ixi of Fuck Yeah Good Omens has even kindly archived a closeup of the aftermath, for Crowley, of "Buck up!" In gif 4, above, you can see that the tiny smile is an involuntary reaction that happens as Crowley's eyes widen: for a fraction of a second, he's caught off-guard. In the closeup it's easier to see that he suppresses the smile and gives a tiny shake of his head, Eyebrows of Disbelief heading for his hairline.

There are a number of things Crowley's reaction could mean and what messages it could communicate (we'll get to that in a sec), but regardless, his reaction is, unquestionably, one of surprise and suppressed amusement. This is an aspect of Crowley and Aziraphale's relationship and characters that I like very much, viz., that one of the reasons Crowley likes Aziraphale (though Aziraphale is judgy and occasionally, unintentionally, horrifyingly cruel) is that in addition to being one of the kindest and most courageous beings in existence, Aziraphale is mad as a bag of frogs. Crowley does not know what is going to come out of Aziraphale's lovely mouth next, but Crowley does know there's a good chance he will struggle to believe he's hearing it, and Crowley likes that.

That's what makes this my favorite moment. What makes this moment so cool and rad, though, is its ineffability. We know from the Eyebrows of Disbelief that Crowley is surprised and amused, but any of several things could be read in that almost imperceptible headshake. Like:

What are you doing? or

Why are you like this? or

How can you be aware that you say these things out loud and yet still say them out loud? or

How has my existence come to this? this moment of listening to such insanity?

each of which is a fair and just feeling to have/message to communicate to a man(-shaped entity) who is yelling "Buck up!" at Hamlet.

But that's only if we read Crowley's amusement as being at Aziraphale's expense. And I don't think we should. Because watch Aziraphale here:

He's doing it on purpose. He is shouting a hilariously inappropriate, 100% authentic Aziraphale-brand thing over arguably the gloomiest passage of Shakespeare's famously gloomy play--right after Crowley complains about its gloominess--and he is watching Crowley as he does it. Look at his smile! He knows he's being Deeply Uncool, and he is doing it literally right into Crowley's face.

Remember that we just talked about how by this point in the chronology Crowley and Aziraphale have learned to communicate with each other nonverbally through facial expression? So what does it mean when Aziraphale responds to Crowley's grumbling about Hamlet's gloominess by smiling his minxious Mona Lisa Aziraphale smile, looking right into Crowley's face, and yelling at Hamlet to buck up? Aziraphale, in a carefully coded, carefully Aziraphale way, is joking with Crowley. His silliness in this moment is for Crowley.

So with aaaaaaallllll of this essay in mind, what does it mean that Crowley's reaction to "Come on, Hamlet! Buck up!" is widening eyes, an involuntary twitch of his mouth toward a smile, and then, his eyebrows still showing surprise and amusement, a tiny shake of his head?

Once more, with inferences:

I do propose, y'all, on the basis of this web of evidence I submit for consideration, that what we are seeing here in my favorite moment of Good Omens is the ineffable equivalent of Aziraphale and Crowley sharing a laugh.

Crowley's amusement here isn't at Aziraphale, because Aziraphale is eliciting that amusement consciously and deliberately. Aziraphale, in good spirits and happy to see Crowley, uses his Aziraphaleness to offers Crowley not only an opportunity for amusement, but the opportunity to be in agreement with him about what in this situation is funny. They're on the same side of this joke.

And his humor lands just as he wants it to: Crowley, just for a moment, is caught off-guard, and tickled--

But remember, Crowley is worried in this scene about being surveilled ("I thought you said we'd be inconspicuous here"), and he worries about audio surveillance a lot ("Walls have ears"; "Don't say that. If my lot hear [etc.]," etc.), so he's very limited in what reactions he can show or voice. Aziraphale knows Crowley must be perceived by anyone watching or listening to disapprove of his, Aziraphale's, behavior (just as he must be perceived to disapprove vociferously of Crowley's). Both of them know this.

--so Crowley suppresses the smile almost successfully, and shakes his head at Aziraphale, minutely, to say Stop. What you're doing is working, you're close to making me laugh, and if I show how much you have just delighted me, it will blow our cover of "just an Arrangement."

I offer three final data points in advancing my argument that what we see in my favorite Good Omens moment is Aziraphale successfully attempting to joke with Crowley and Crowley recognizing that overture from Aziraphale and being momentarily surprised into a reaction of genuine delight before pulling his face back under control and indicating to Aziraphale that he must stop:

Datum 1. Nothing going on with Crowley's face in this moment is accidental. We know for sure we're not seeing David Tennant react to Michael Sheen here not only because of literally every other point of Tennant's and Sheen's performances in the show, but because Tennant is wearing opaque contacts and sunglasses under film lighting and therefore cannot be reacting to anything more compelling than a level-10-lift blur because Tennant cannot see shit. Crowley's reaction is a deliberate and careful performance choice on Tennant's part, and it's underscored by director Douglas Mackinnon's choice to film Tennant in 1/2 profile to keep Crowley's eyes visible and face readable to the audience. This reaction is supposed to be there and supposed to be meaningful.

Datum 2. The husbands in 1601 is not the only moment in Good Omens when we may be seeing an angel and a demon communicate the message Stop doing that, it makes us look too familiar between themselves with a little headshake:

Datum 3: There is another moment in Good Omens when Aziraphale offers Crowley the opportunity to enjoy a joke with him. There, too, his humor lands just as he intends, so we can use this other moment as a comparison to our 1601 moment. I don't have gifs for it, but go back and watch it, S1E6 49:27-42. Snips below.

Aziraphale says something that surprises and amuses Crowley (he asked Hell for a rubber duck while he was sloshing around in the holy water)--

--but what Aziraphale says makes Crowley smile long before it makes him laugh.

In fact, his laugh, though a genuine cackle, is quite delayed, and he laughs only after Aziraphale starts laughing too.

In other words, Crowley's reaction to Aziraphale offering him amusement they're both on the same side of is exactly the same as his reaction to "Come on, Hamlet! Buck up!" right up until he laughs instead of shaking his head. Here, after Armageddidn't, Crowley doesn't have to suppress his reaction, so he can let the smile bloom; he doesn't have to control his response, so, although it takes him a few extra seconds, he lets the smile turn into a laugh.

But in 1601, it's not safe to laugh at Aziraphale's humor. It's not safe even to smile at him. A single piece of evidence or eye/earwitness testimony that he and Crowley have anything more friendly than the most passing and acrimonious of professional relationships could mean death to either or both of them, and depending on what Falling is like, maybe something worse than death for Aziraphale.

But Aziraphale is so funny, so effervescent for Crowley, at Crowley, that it catches Crowley just for a moment. Crowley's eyes widen and the corner of his mouth twitches toward a smile.

And that's dangerous. If Aziraphale keeps acting so charmingly mad, Crowley is going to laugh, and they can't afford that risk, so he shakes his head at Aziraphale. Stop, or I won't be able to keep a straight face around you.

And Aziraphale apparently receives that message, because he immediately eases off. Less than 60 seconds later we learn that he's deeply concerned for Crowley's safety--and that it's not so much that Aziraphale has Crowley wrapped around his little finger as it is that Crowley has wrapped himself around Aziraphale's little finger like a snake arranging itself on the tree branch it calls home.

UPDATE 14/10/23: HOLY SHIT Y'ALL IT GETS EVEN BETTER! THERE IS A SEQUEL!

#good omens#good omens meta#good omens 1601#good omens microexpressions#good omens headshake#angelfish#aziracrow#ineffable husbands#good omens fanalysis

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Another Post About Crowley's Terrible Handwriting

Actually his handwriting here isn't terrible, it's just, like Anathema's spelling, 300 years too late.

So first, I posit that we can be reasonably confident this is Crowley's handwriting because he is very likely the only celestial being besides Aziraphale who can spell devourer correctly.

Crowley has taken more care than usual with his penmanship today because this is a Fancy Presentation, and there are some delightful things to note about it:

--The beautiful serifs on each letter and variation in width of the strokes (the lowercase r's especially)

--Enthusiastic but intermittent capitalization of nouns

--The L that ends "Hail" is a small capital like the ones used in the Bible to spell LORD; the l in Worlds is lower-case

--The lozenge shape of the letter o

--Both s-es are oversized and dip below the writing line

--The kerning is terrible, the script wanders off the writing line at several points, and the location of the writing line is not imagined consistently

I am not an expert in the history of handwriting, but every single point of this suggests to me that Crowley learned to write in English in the late 16th or early 17th century, between say 1570 and 1620, and he learned to do it by copying printed material, not somebody else's handwriting. And it looks like late 16th-century writing. Or rather, like somebody learned to write by copying late 16th-century print and hasn't practiced enough for his style to change significantly in the last 400-500 years.

This means Crowley would have learned using a quill pen, poor devil, and if that's true no wonder he doesn't do it more often. (I wonder if this is why he now owns a pen that looks like it can break the sound barrier; if the Bentley is a permanent replacement for the loathsome, buttocks-abusing horse, maybe he keeps the expensive pen as self-reassurance that he'll never have to write with a quill again.) Quill pens would explain the lozenge-shaped o's: quills can only make a downstroke, so writers who used them shape o's as lozenges made of four downstrokes. Someone who learned writing with a quill would shape his o's like a calligrapher.

16th/early 17th century is the earliest I think Crowley would have learned to write in English because before that there was no block print; there was no print at all, only handwritten scripts of varying legibility, none of which look remotely like Crowley's handwriting does.

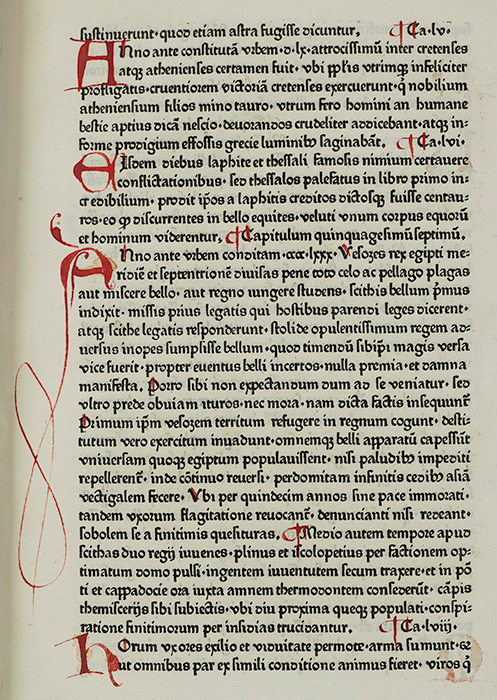

Here's what print looked like in Germany in 1471 (printing does not arrive in England for another 5 years after this):

The printing press showed up in England in 1476. Between 1500 and 1600, England got its shit sorted out wrt fonts and typesetting and started turning out what we would recognize today as readable material.

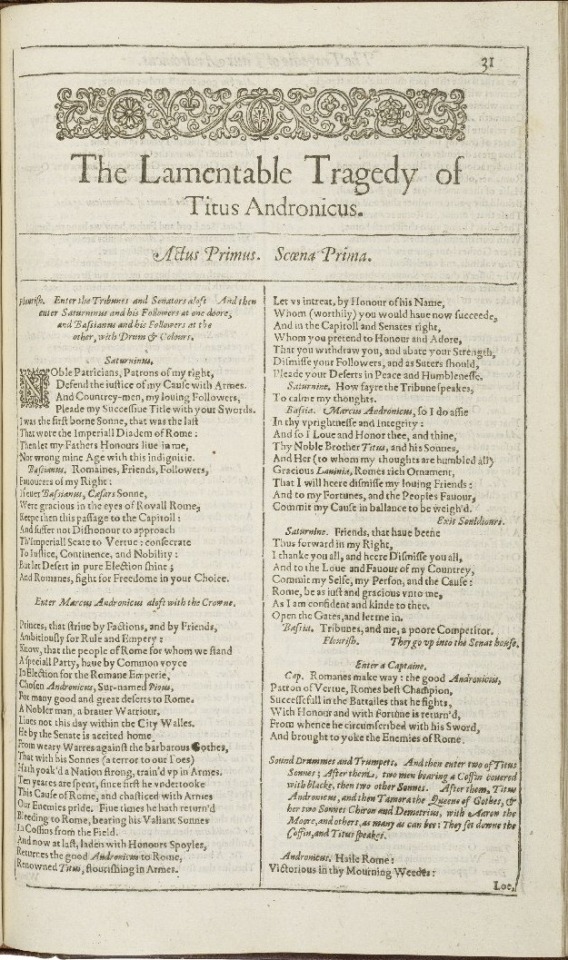

Here's what English printing looked like in 1623, c. 150 years after the German one above:

Not bad, right? I've received Xerox copies less legible than this in classes I paid for. I think it is likely based on his handwriting that Crowley learned to write from printed material a decade or two older than this. The adornments Crowley puts on his letters are serifs, not ligatures: these are not letters that were ever meant to join up in cursive, but letters that were copied from typeset.

From the 16th through the mid-19th century, variations in how a handwriter capitalized letters were very common, and two of these variations show up in Crowley's writing as well.

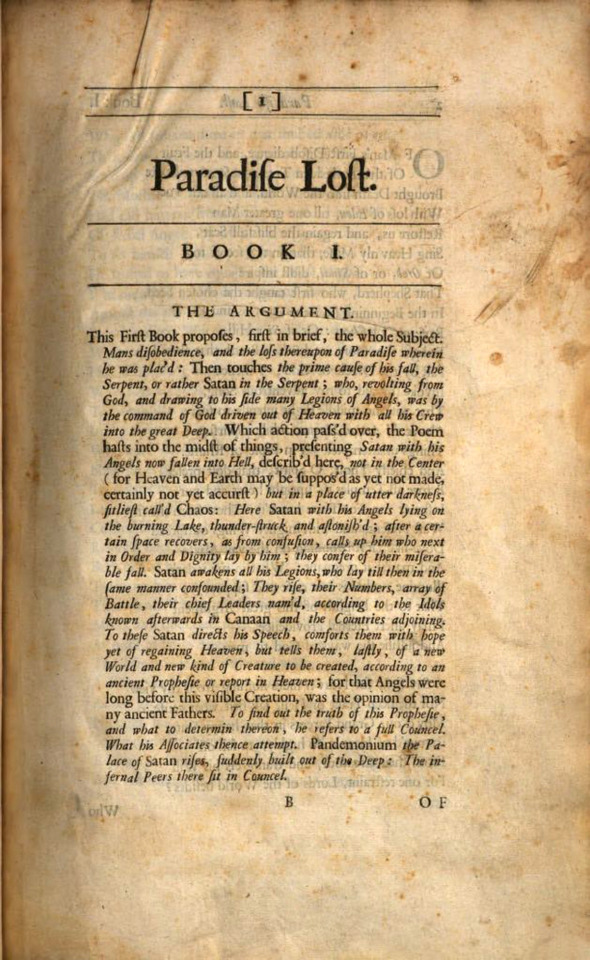

First, English inherited from German the capitalization of all its nouns. You can see it in Titus Andronicus, above (1623). Due to variations in education and taste, this quickly shifted to capitalization of whichever nouns the writer (or publisher, or printer) felt were important to capitalize, as you can see in Paradise Lost from 1688, below. Hail the Great Beast, devourer of Worlds.

Second, It was also very common during this time to capitalize terminal letters of words, either as a sign to the reader that previous letters had been omitted or because writers using quill pens wanted to be sure readers knew what letter they were looking at through the smudges and weird spacing and general wretchedness of the reading experience imposed by quill writing. I think this latter reason may be why Crowley writes "HaiL" when his other letter L, in "Worlds," is both lowercase and carefully printed with a pretty serif.

Handwriters in English between 1500 and 1800 also had a major hard-on for abusing the letter s, which was shaped like a lowercase f (to contemporary eyes) or a loose S, either of which drop below the writing line. Here's an example in print from 1688:

Use of the long S in print fell out of favor and disappeared abruptly in the UK after 1800.

Crowley's S-es could be a holdover from this: they both drop below the writing line, and they're both oversized.

What I think we can say for sure is that he's not very good at writing s-es, so they always turn out bigger than he intends. The S in "Beast" is noticeably different at the left curve than the S in "Worlds," which I would expect for someone who hasn't written thousands of s-es yet, and the S in "Worlds" looks very much like someone has faithfully rendered a shape they have seen rather than written a letter. Since he can write a letter r elegantly but can't do a curved s, it suggests to me that he hasn't had as much practice doing the curved s yet as he has the other letters, which fits with someone used to writing a long s 75% of the time.

Even the kerning speaks to me of someone who learned to write with a quill: leaving (comparatively) large spaces between letters gives the ink somewhere to drip and smudge without rendering the letter illegible.

There's one other reason I think Crowley probably learned to write in English in the 16th century: He's lazy, and he probably wouldn't have needed to know before then.

The movable-type press arrived in England in 1476. The Protestant Reformation kicked off in England c. 60 years later in 1534 when Henry VIII declared himself head of the English Church. Prior to the surge in literacy among the wealthy and merchant classes in the 16th century, thanks to this intersection of printing press and Protestants (who believe it's important that each person read the Bible for themselves), almost no one knew how to read, including most of the gentry and nobility, and still fewer knew how to write. If you had a message, you sent a guy or you showed up yourself. If you had something you wanted recorded, you summoned a scribe. If you needed to know something, you found somebody who knew and you asked them.

By the time of Queen Elizabeth's accession in 1558, 82 years after William Caxton began operating England's first movable-type printing press, a fully literate royal court were passing each other and their spies and their assassins gossipy notes like everybody was a 12yo in math class. Elizabeth wrote letters and poems. Among the gentry gentlewomen replaced monks as the medical caregivers for their communities (bc Henry shut down all the monasteries), and they wrote and shared and copied multi-generational "receipt books" and herbals of medical and cosmetic treatments. In the space of a single generation, literacy--the ability to write, not just to read--became a prerequisite for functioning in the upper echelons of society.

So if he didn't already know by then, Crowley would have needed to learn to write in English in the mid-16th century. And he would have had to learn it with a quill. (Wearing black probably came in handy for all the ink he spilled or dripped on himself.)

Last to consider is the W in "Worlds," which has no serifs and is not written with any particular attempt at straightness or symmetry. To me this suggests that Crowley learned to write w's from a modern reference, not his original reference. And this makes perfect sense: w was very much in use in the 16th century in English, but nobody agreed on how to write or print it, so there were crossed v's, two capital U's, and this weird gothic lowercase n with extra tentacles. W, Crowley would have learned, always needs to be checked up on before you commit.

Crowley's spelling here is modern, which is frankly a huge achievement for someone who was present for the formation and transformation of all 3 English languages. The contemporary Modern English we use today was a going concern for over 2 centuries before anyone wrote an English dictionary, and it was three centuries before dictionaries became authorities on how to spell correctly and people started giving a shit about that. (Before that as long as people could read the word and understand what you meant by it in context, you'd spelt it correctly.)

Taken together, the W and the modern spelling suggest that although Crowley almost never writes by hand, he reads regularly. This matches with two Words of God I've seen from Neil Gaiman (which I am too lazy to find and link) in which he mentions that Crowley likes to read but won't admit to doing so or to liking books.

Aziraphale should get him a book about ducks for Valentine's Day.

65 notes

·

View notes