#findlay bike race

Text

Jack Findlay

251 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Nervously awaiting the start of the 2010 Makara MTB Creek to Peak relay race alongside mtb stalwart and trailbuilder extraordinaire Ricky Pincott and my mate and closest opponent Matt Isaac behind me. 14th out of 15 teams wasn't perhaps the best result, but it was a massive win for me as my teammate was my son Kester in his first ever bike race! 📷 Ross Findlay (at Makara Peak Mountain Bike Park) https://www.instagram.com/p/CT-1PdShPXk/?utm_medium=tumblr

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

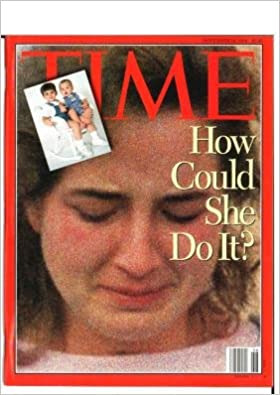

The Mommy Myth: Threats from Within (Part Three)

Just some Didi Pickles anxiety for you before we start ahead, I think we’d all feel this way.

We start with the Lisa Steinberg (buried as Elizabeth “Lisa” Launders) case where a six year old was abused to death by her adoptive father Joel Steinberg while her mother Hedda Nussbaum looked on (and was abused herself), there is still some controversy as to whether Hedda was an accomplice to her daughter’s abuse and death, or if she’s merely a victim in her own right (also Joel is walking around free after parole). Media coverage of child abuse have improved, being kicked off by the publication of Mommie Dearest by Christina Crawford and Oprah even covering it in her show “Scared Silent”, interview with Michael Jackson, her disclosure of childhood trauma, and her coverage of child abuse in a Montana town. The darker side is that the coverage overtly covered Black or Latina mothers and were aimed at underfunded and understaffed child welfare services (without assigning culpability to the government and agency support or lack of it) and these stories didn’t address structural problems like unemployment, poverty, generational trauma, racism, etc. Instead they came up with “the Maternal Delinquent”, who was more shocking and newsworthy than fathers who murdered and abused their children.

youtube

We talk about Susan Smith, where the story starts off with a 23 year old woman’s Mazda being carjacked by a “black man in a ski mask”, taking her car and her two young children (age 3 and 14 months, respectively). An alert was put on for the suspect and the whole community (the small South Carolina town of Union) went on a search for the boys while their separated parents went on national television to beg for the safe return of the boys, while David Smith could barely keep himself together, Susan was very composed (they had filed for divorce) causing many viewers to speculate if the two of them or one of them were involved in the kidnapping. This led to Susan saying that it’s so hurtful someone would think that of them and then hours later, Susan Smith confessed to the FBI that she had driven her car into the lake John D. Long with the kids in the backseat and let the car roll off the boat ramp into the deep murky waters of the lake. This also occurred around the same time as the O.J. Simpson trial so it was a time where people were really tuning into their screens where there was coverage up until Smith was sentenced in late July 1995. The community (that supported her and her family) were chanting “baby killer” at her on her way to the courthouse and it turned out that she had been dating the most eligible (and wealthy) man in town, Tom Findlay, who didn’t want to get involved with a woman with children, so she went La Llorona on them. Here’s a break from Coco:

youtube

I don’t have to tell you that when reading these stories that you can feel free to take time to go outside, smell fresh air, cuddle puppies or look at pictures of puppies. But I will continue:

She became Time magazine’s cover girl, people built a shrine to the boys on the lake’s bank, including mothers with their children while they asked “How could a Mother do that to her children?” with one African American mom (one of the skimpy times where moms of color were shown in a more positive life than white mothers) snarking: “She couldn’t eat ‘cause they were hungry, she couldn’t sleep ‘cause they were cold. I guess she couldn’t take a bath ‘cause she thought they was drowning.” The news was a shock to a lot of people, even her ex husband insisted she was a dedicated mother in interviews, but she bamboozled law enforcement, viewers, a whole town, the media, and set the southern African-American community on high alert (look up pogroms and look up the Springfield race riot) and she reminded people that motherhood may be an act. It also made people wonder: are kids just commodities to their parents? The further coverage was worse: they figured the kids were aware when they went in the water (there goes my hopes that they were asleep then). The Union County Sheriff’s office re-created the crime with cameras in a car so people and see and feel what it was like for the boys to go under, then was aired by the networks; at a time when mothers were told to put themselves in their childrens’ shoes and see the world through their eyes, it was jarring. There were two women from the community who cried over the idea of these two little boys and their last moments.

Speaking of horror and children, it turned out that Susan Smith’s stepfather, a member of the conservative Christian Coalition, had been sexually molesting her since she was sixteen and (according to his testimony) was still having sex with her and her own father committed suicide when she was six (a social worker said she tried to press charges but the sheriff said the case was closed and “it’s file disappeared”); Susan even attempted suicide as a teenager. David Smith testified he doesn’t know what to do now his kids were gone and he had plans to see them grow up and teach them how to ride a bike and go fishing. A Newsweek poll revealed that 63% respondents said she should receive the death penalty. The trial even revealed that white picket fence small towns like Union, with it’s churches numbering over 100, would have it’s dark secrets and Tom Brokaw said, “And in every small town in America tonight residents comfortable in the sanctuary of their familiar surroundings are wondering, ‘What’s going on here that we don’t know about?’”

Instead of probing “how could she?”, the media focused on sentimentalization with Medea Syndrome with even Cosmopolitan magazine taking time away from blow jobs and the thing that Sir Mix A Lot ain’t down with, saying there were a lot of mothers killing their children. And then we met the moms who made mistakes that are so fatal: Lisa Beth Hathaway, mother of Jessica Dubroff. The “miniature Sally Ride” who wanted to be a pilot and was already training to be a pilot and was flying with her instructor and father from Half Moon Bay to go across the country, the weather wasn’t that great and the plane crashed and killed all the passengers. Her father, Lloyd Dubroff was blamed for pushing her to be the next Amelia Earhart, but mom Lisa was portrayed as a monster...although if everything went right she would have been held as an example of exemplary mothers raising exceptional kids (just sayin’). The moms interviewed were outraged at Lisa’s permissiveness and at the fact that she said she wouldn’t have kept Lisa from doing it because it’s her dream (if she did keep her, we’d say she was toxic). Then she was grouped with Wanda Holloway, Brooke Sheilds’s mom, Macaulay Culkin’s dad, and Steffi Graf’s dad as a “pushy parent”. She just wanted her daughter to be happy is all that is, but the media went on to drag her through the mud when they saw she was a hippie feminist who didn’t play a TV and gave her musical instruments for her daughter, now mothers were policed in private even if their husbands did the fucking up. If things had gone right, Lisa would have been congratulated for raising an exceptional daughter with a variety of talents. She has written a book about her daughter.

The hand wringing went on with their coverage of teen moms like Melissa Drexler and Amy Grossberg, who gave birth and abandoned their babies in the trash outside. Newsweek covered the stories and similar ones, suggesting an epidemic. There was no exploration of how US culture uses sex to sell everything and turns around tells kids to “just say no”, the poor state of sex ed in a country where people are too squeamish to discuss sex in a clear and mature manner, or why was dumping a baby in a dumpster the only viable option?

These stories affected how moms were looked and judged and the public vilification covered was designed to keep moms on their toes and never let your guard down, or you will be condemned. Also do it all yourself Mom.

#The Mommy Myth#meredith michaels#susan j douglas#women in media#motherhood#1980s#1990s#motherhood in media#mothers#Susan Smith#Prom Mom#Sensationalization#Sexism#Time magazine#Child Abuse#Parents who murder#Rugrats#Didi Pickles#Charlotte Pickles#Betty DeVille#Medea Syndrome#Lisa Beth Hathaway#Jessica Dubroff#newsweek magazine#cosmopolitan magazine#Teen Moms#Sexualization#Sex Education#Indie Sex#Sex in the media

1 note

·

View note

Text

IRONMAN 70.3 Indian Wells – La Quinta – Race Recap

* A video version of this race recap can be found on my YouTube channel here.

A triathlon is a game of contradiction.

You spend hours, weeks, months training for something that lasts moments of your life. Improve at one sport by mastering three. Train slower to race faster. Race slower to race faster. Do it alone, surrounded by people. Never see a finish line as the end.

One of the most challenging contradictions is the trap of identity. To do well, you have to immerse yourself in training for long periods of time. It can become you; consume you. And then what is objectively a meaningless act of physical exertion assumes a station in your life that it never deserved. And you are left with nothing but finish times and medals, to gather dust because nobody cares.

I thought about these contradictions a lot during my training for my first Ironman 70.3 race in Indian Wells – La Quinta California. It seemed fitting in this vein of contradiction that I would train in the cold and snow in order to race in the warm desert. I hoped that by recognizing the contradictions inherent in what I was doing, I could avoid that most challenging trap, and come away with an experience, rather than just another race.

After Musselman in July, I took a break for a few weeks, and then started training again. I had a few minor injuries, which were challenging, but for the most part my training was consistent. I did some bike fitting and got a set of aerobars on my bike. Winter arrived early in Vermont; we had snow on the ground before Thanksgiving. So most of my riding was indoors. I ran outside as much as I could. And weather doesn’t matter in the pool, of course.

Swimming was a major area of focus for me this fall. I got a second swim analysis and really worked on my technique. I was able to take another ten seconds off my 100-yard time, and by December I was swimming faster on average than I ever had.

I had also been trying to eat smarter, both to be healthier and to drop extra weight. With the help of a friend, I definitely had some success here, though it added some stress to our family routine. Kids like what they like.

I was a little concerned about flying my bike to California, because I had only done it once before and I didn’t have to assemble it myself when I arrived that time. So I broke it down and packed it up at the bike shop so I could get guidance with questions that I had and hands-on help from Darren, my friend who owns Vermont Bicycle Shop. I felt a lot more confident once it was all ready to go.

The flights were pretty uneventful, and we made it to San Diego in one piece — including my bike. One of the first things I did was put it back together; I wanted to make sure I would have enough time to solve any problems that came up. Luckily, there didn’t seem to be any and the assembly went pretty smoothly.

The Catamount, my custom Orbea Terra, ready to ride

We spent a few days with my brother’s family in San Diego, hiking at Torrey Pines and playing on the beach. It was a nice way to get acclimated to the environment. It wasn’t as warm as I thought it would be, but it definitely was a lot warmer than Vermont. Locals on the beach were dressed in winter coats and hats, but our girls thought it was the perfect weather for swimming in the Pacific.

Before long it was time to drive to Indian Wells. The amazing scenery on that drive took us all by surprise. We stopped for a moment but the day before the race was very busy so there wasn’t a lot of time for sight-seeing.

After getting the family settled at the hotel, I had my first Ironman athlete check-in experience and got to see the pro panel, which included the eventual race winners Lionel Sanders and Paula Findlay. I checked my run gear in to T2, a little overwhelmed by the enormity of the transition area. Then it was time for a half-hour drive to the swim start and T1, to see the swim course, check in my bike and decontaminate my wetsuit before hanging it on the racks where it would stay until race morning. I made sure to mark it well so I wouldn’t have any trouble finding it.

My day would have gone quite differently if it hadn’t been for my teammate Lacy. She and her husband gave me a lift to the shuttle buses, which was already a great help by itself, but when she mentioned her water bottles I realized I had forgotten something at the hotel. Specifically, all of my hydration. It was still sitting in my refrigerator. They drove me back so I could retrieve them and I was so grateful. Luckily we were up early enough that it didn’t affect our day — we got on a bus with no waiting and were off to the start area.

I knew the water would be cold. The reported temperature that morning was just under 59 degrees. There was no warm-up swim. We stood in line at the rolling start for a long time before finally getting into the water. And then, finally, after everything, I was racing.

The first one or two hundred meters were tough. I was hyperventilating from the shock of the water temperature and struggling to relax and find my rhythm. I expected that, but it didn’t make it any easier. Finally I settled in, though, and found my zone. It was clear pretty quickly that I should have seeded myself further forward; nobody around me was actually swimming at the pace they lined up for. I was crawling over people all the way. My goggles half-filled with water but I ignored it since I could still see. When I finally crawled out of the lake, I had a personal best time of 34 minutes. By my watch, I had swum ten seconds per 100 yards faster than my first 70.3 in July.

As I mounted my bike, I readied myself mentally to face the biggest contradiction of the day. I had programmed the wattage target my coach and I agreed on into my bike computer, and I was going to stick to that number like superglue. The paradox of my plan was that the number was low. It was lower than I had expected. It was lower than it was at my first 70.3, and it was low relative to my power profile. It was so low that it meant I’d be doing what amounted to a zone 2 ride for the entirety of the bike leg.

The plan was predicated on the knowledge that the course was pancake flat, and that triathlons succeed or fail on the run. We would conserve energy on the bike, allowing my inertia to do most of the work, and hopefully get off the bike with enough in the tank to really drop the hammer.

So what the bike ended up being was a test of patience, rather than fitness. My heart rate stayed low, peaking only at the very start during the excitement of transition and climbing a tiny hill out of transition. I spent a lot of the time focused on avoiding drafting as much as I could, but it was pretty difficult considering that the roads were absolutely packed with riders. That forced me to surge occasionally, but it was okay because the course was so flat.

The first 20 miles flew by so fast that I was actually surprised when I saw the mile marker sign. At 30 miles I felt no worse; very comfortable and just cruising along. It was a strong contrast to my last race, where the 30 mile marker saw me doing pretty solid work. I began to get excited about the paradoxical plan as evidence in its favor continued to build. That naturally inclined me to want to push harder, but I redoubled my efforts to stay focused and in my target zone.

The highlight of the bike course by far was the Thermal Raceway, which is a private racetrack for cars that we got to ride around on. My watts went up on that section for sure, but it was a match that was worth burning. It’s a unique experience to ride your bike around a banked track with perfect pavement, designed for million dollar super cars. I had a lot of fun there.

The rest of the course was technically uphill but the gradient was so gradual, I barely noticed. I rode into T2 just 2 watts over my target. My family was cheering at the dismount line, which was a nice boost going into the start of my run.

After racking my bike and strapping on my running shoes, I started out on the final leg, to see if the contradictions would be resolved. Here I was, running in the heat and sun after training for months in the cold and snow. Here I was, having biked slowly on purpose to see if I could do a faster race. And here I was, after weeks of training at a jog, pushing my legs to go fast, and stay fast.

I have always run fast out of transition, because it takes a mile or two before my legs really feel normal and I can tell how my body is actually doing. At my first 70.3, I slowed that pace after the first aid station, feeling that I would have to conserve energy to make it through the run without shutting down. This day, though, I felt strong. I felt no such impending decline. I felt like I could hold the pace. So I didn’t slow down.

The run followed asphalt roads for a couple of miles before turning off onto a golf course, where it tracked around the greens on a winding, undulating path that was a mix of concrete, dirt and grass. There were no long straightaways, no places to hide from the course. It was highly dynamic and constantly changing.

A conclusion I had drawn from my first 70.3 was that I had been underfueled. This time, I ate and drank everything I could get my hands on during the run. I think I probably ate two or three whole bananas, a half at a time, plus several gels and all the coke, gatorade and red bull I could grab. I didn’t slow down during the aid stations; I didn’t want to lose my inertia. At one point I took a cup of ice, dumped it in my hat and packed it onto my head. The contrasts had never been more stark — at home I had been wearing winter hats to keep the snow off my head; today, I was deliberately packing ice onto my scalp.

It was a two-lap course which meant that I had to run agonizingly close to the finish line at around mile seven, only to have to turn around and do the entire thing one more time. Now I knew what to expect, though, and I knew where to push and where I could relax. Now all I had to do was hold my pace.

When the second lap of the course started to beat me, I focused on my family, waiting for me at the finish, and steeled myself in the resolve to make this all worth it. What was the point of asking so much of them, to support my training, to spend an entire day of our vacation standing around, if I didn’t make it worth it? I wasn’t going to slow down for anything.

The last couple of miles were hard and my pace started to slip a little bit, but I was still moving faster than I had ever really expected. I found my family just before the finish line, gave everybody high-fives, and then took it over the line. It was a personal best by a long margin, with personal records in every part of the race. I almost couldn’t believe it, but there it was.

If there’s one thing I learned from this race experience, it’s that you can’t always see contradictions as obstacles. Sometimes, they are puzzle pieces in a larger pattern that you can’t fully recognize until you’ve put it all together. You can’t always resist the things that don’t make sense; sometimes, you have to lean into them, make them part of your plan and see them through to the end. And that’s when you can find clarity.

We closed out our trip with a drive through Joshua Tree National Park, marveling at the natural beauty of the desert before boarding our plane to fly back into winter. With California behind us, it was time to look forward to a new year, and new contradictions.

Watch the video version of this race recap:

youtube

from WordPress https://ift.tt/2TjeA98

via IFTTT

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Professional Triathlete’s Organisation (PTO) has today revealed the full teams for the inaugural Collins Cup, which is due to take place later this month. Eight triathletes qualified for each of the three teams earlier this week via the automatic qualification spots, which are based on the athletes’ performances over the past two or three years. Today, the team captains of each team have revealed their picks for the final four spots in each team. Check out the full team line-ups below. Who’s in Team Europe? The eight athletes to gain a spot via automatic qualification were: Jan Frodeno (GER) Daniela Ryf (SUI) Gustav Iden (NOR) Anne Haug (GER) Joe Skipper (GBR) Lucy Charles-Barclay (GBR) Patrick Lange (GER) Holly Lawrence (GBR) Team captains Normann Stadler and Natascha Badmann (who recently replaced Chrissie Wellington) have now confirmed their four picks to complete the team: Kat Matthews (GBR) Emma Pallant-Browne (GBR) Sebastian Kienle (GER) Daniel Bækkegård (DEN) Who’s in Team USA? The eight athletes who achieved automatic qualification to Team USA were: Sam Long Skye Moench Rudy Von Berg Heather Jackson Matt Hanson Jackie Hering Ben Kanute Chelsea Sodaro Team USA captains Mark Allen and Karen Smyers have also picked: Katie Zaferes Taylor Knibb Chris Leiferman Justin Metzler Who’s in Team International? Team International’s eight automatic qualifiers were: Lionel Sanders (CAN) Teresa Adam (NZL) Braden Currie (NZL) Paula Findlay (CAN) Samuel Appleton (AUS) Carrie Lester (AUS) Max Neumann (AUS) Jeanni Metzler (RSA) Captains Lisa Bentley and Simon Whitfield have also picked: Ellie Salthouse (AUS) Sarah Crowley (AUS) Jackson Laundry (CAN) Kyle Smith (NZL) What is the Collins Cup? Taking inspiration from golf’s Ryder Cup and organised by the Professional Triathletes Organisation (PTO), the competition is due to take place on 28 August 2021 and will pit the three teams above against each other in pursuit of glory and a prize purse of $1.15m. The race itself will be a middle-distance non-drafting format (1.9km swim, 90km bike, 21.1km run) with each team putting forward one athlete to race against each other in a three-person ‘matchplay’ battle. Each team member will need to battle their own three-person individual contest. The 12 races will be staggered 10 minutes apart with the points from each individual race deciding who will be crowned overall winners. Top image credit: Stephen Pond/Getty Images for Challenge Triathlon https://ift.tt/37E20Ya via 220 Triathlon https://ift.tt/3lXxqBc }

0 notes

Text

With No Legal Guardrails for Patients, Ambulances Drive Surprise Medical Billing

School librarian Amanda Brasfield bent over to grab her lunch from a small refrigerator and felt her heart begin to race. Even after lying on her office floor and closing her eyes, her heart kept pounding and fluttering in her chest.

The school nurse checked Brasfield’s pulse, found it too fast to count and called 911 for an ambulance. Soon after the May 2018 incident, Brasfield, now 39, got a $1,206 bill for the 4-mile ambulance ride across the northwestern Ohio city of Findlay — more than $300 a mile. And she was on the hook for $859 of it because the only emergency medical service in the city has no contract with the insurance plan she has through her government job.

More than two years later, what was diagnosed as a relatively minor heart rhythm problem hasn’t caused any more health issues for Brasfield, but the bill caused her some heartburn.

“I felt like it was too much,” she said. “I wasn’t dying.”

Brasfield’s predicament is common in the U.S. health care market, where studies show the majority of ambulance rides leave patients saddled with hundreds of dollars in out-of-network medical bills. Yet ground ambulances have mostly been left out of federal legislation targeting “surprise” medical bills, which happen when out-of-network providers charge more than insurers are willing to pay, leaving patients with the balance.

However, the COVID-19 pandemic has prompted temporary changes that could help some patients. For instance, ambulance services that received federal money from the CARES Act Provider Relief Fund aren’t allowed to charge presumptive or confirmed coronavirus patients the balance remaining on bills after insurance coverage kicks in. Also during the pandemic, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services is letting Medicare pay for ambulance trips to destinations besides hospitals, such as doctors’ offices or urgent care centers equipped to treat recipients’ illnesses or injuries.

But researchers and patient advocates said consumers need more, and lasting, protections.

“You call 911. You need an ambulance. You can’t really shop around for it,” said Christopher Garmon, an assistant professor at the University of Missouri-Kansas City who has studied the issue.

A Health Affairs study, published in April, found 71% of all ambulance rides in 2013-17 for members of one large, national insurance plan involved potential surprise bills. The median out-of-network surprise ground ambulance bill was $450, for a combined impact of $129 million a year.

And a study published last summer in JAMA Internal Medicine found 86% of ambulance rides to ERs — the vast majority by ground ambulances, not helicopters — resulted in out-of-network bills.

Caitlin Donovan, senior director of the National Patient Advocate Foundation in Washington, D.C., said she hears from consumers who get such bills and resolve to call Uber the next time they need to get to the ER. Although experts — and Uber — agree an ambulance is the safest option in an emergency, research out of the University of Kansas found that the Uber ride-sharing service has reduced per-person ambulance use by at least 7%.

Only Ambulance in Town

When Brasfield was rushed to the hospital, her employer, Findlay City Schools, offered insurance plans only from Anthem, and none included the Hanco EMS ambulance service in its network. School system treasurer Michael Barnhart said the district couldn’t insist that Hanco participate. Starting Sept. 1, Barnhart said the school system will have a different insurer, UMR/United Healthcare, but the same plans.

“There is no leverage when they are the only such service around. If it were a particular medical procedure, we could encourage employees to seek another doctor or hospital even if it was further away,” Barnhart said in an email. “But you can’t encourage anyone to use an ambulance service from 50 miles away.”

There is great disagreement about what an ambulance ride is worth.

Brasfield’s insurer paid $347 for her out-of-network ambulance ride. She said Anthem representatives told her that was consistent with in-network rates and Hanco’s $1,206 charge was simply too high.

Jeff Blunt, a spokesperson for Anthem, said that 90% of ambulance companies in Ohio agree to Anthem’s payment rates; Hanco is among the few medical transport providers that don’t participate in its network. He said Anthem reached out to Hanco twice to negotiate a contract but never heard back.

Brasfield sent three letters appealing Anthem’s decision and called Hanco to negotiate the bill down. The companies wouldn’t budge. Hanco sent her a collections notice.

Rob Lawrence of the American Ambulance Association pointed out that nearly three-quarters of the nation’s 14,000 ambulance providers have low transport volumes but need to staff up even when not needed, creating significant overhead. And because of the pandemic, ambulance providers have seen reduced revenue, higher costs and more uncompensated care, the association’s executive director, Maria Bianchi, said in an email.

Officials at Blanchard Valley Health System, which owns Hanco, said Brasfield’s ambulance charge was on par with the national average for this type of medical emergency, in which EMTs started an IV line and set up a heart monitor.

Fair Health, a nonprofit that analyzes billions of medical claims, estimates an ambulance ride costs $408 in-network and $750 out-of-network in Toledo, which is about 50 miles away from Findlay and has several ambulance companies. Even the higher of those two costs is $456 less than Brasfield’s bill.

Widespread Problem, No Action

Similar stories play out across the nation.

Ron Brooks, 72, received two bills of more than $690 each when his wife had to be rushed about 6 miles to a hospital in Inverness, Florida, after two strokes in November 2018. The only ambulance service in the county, Nature Coast EMS, was out-of-network for his insurer, Florida Blue. Neither had responded to requests for comment by publication time. Brooks’ wife died, and it took him months to pay off the bills.

“There should be an exception if there was no other option,” he said.

Sarah Goodwin of Shirley, Massachusetts, got a $3,161 bill after her now-14-year-old daughter was transported from a hospital to another facility about an hour away after a mental health crisis in November. That was the balance after her insurer, Tricare Prime, paid $491 to Vital EMS. Despite reaching out to the ambulance company and her insurer, she received a call from a collection agency.

“I feel bullied,” she said earlier this year. “I don’t plan to pay it.”

Since KHN asked the companies questions about the bill and the pandemic began, she said, she hadn’t gotten any more bills or calls as of late August.

In an emailed response to KHN, Vital EMS spokesperson Tawnya Silloway said the company wouldn’t discuss an individual bill, and added: “We make every effort to take patients out of the middle of billing matters by negotiating with insurance companies in good faith.”

Last year, an initial attempt at federal legislation to ban surprise billing left out ground ambulances. This February, a bill was introduced in the U.S. House that calls for an advisory committee of government officials, patient advocates and representatives of affected industries to study ground ambulance costs. The bill remains pending, without any action since the pandemic began.

In the meantime, consumer advocates suggest patients try to negotiate with their insurers and the ambulance providers.

Michelle Mello, a Stanford University professor who specializes in health law and co-authored the JAMA Internal Medicine study that examined surprise ambulance bills, was able to appeal to her insurer to pay 90% of such a bill she got after a bike accident last year.

That tactic, however, proved futile for Brasfield, the Ohio librarian. She set up a $100-a-month payment plan with Hanco and, eventually, paid off the bill.

From now on, she said, she’ll think twice about taking an ambulance unless she feels her life is in imminent danger. For anything less, she said, she’d ask a relative or friend to drive her to the hospital.

Kaiser Health News (KHN) is a national health policy news service. It is an editorially independent program of the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation which is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

USE OUR CONTENT

This story can be republished for free (details).

With No Legal Guardrails for Patients, Ambulances Drive Surprise Medical Billing published first on https://nootropicspowdersupplier.tumblr.com/

0 notes

Text

With No Legal Guardrails for Patients, Ambulances Drive Surprise Medical Billing

School librarian Amanda Brasfield bent over to grab her lunch from a small refrigerator and felt her heart begin to race. Even after lying on her office floor and closing her eyes, her heart kept pounding and fluttering in her chest.

The school nurse checked Brasfield’s pulse, found it too fast to count and called 911 for an ambulance. Soon after the May 2018 incident, Brasfield, now 39, got a $1,206 bill for the 4-mile ambulance ride across the northwestern Ohio city of Findlay — more than $300 a mile. And she was on the hook for $859 of it because the only emergency medical service in the city has no contract with the insurance plan she has through her government job.

More than two years later, what was diagnosed as a relatively minor heart rhythm problem hasn’t caused any more health issues for Brasfield, but the bill caused her some heartburn.

“I felt like it was too much,” she said. “I wasn’t dying.”

Brasfield’s predicament is common in the U.S. health care market, where studies show the majority of ambulance rides leave patients saddled with hundreds of dollars in out-of-network medical bills. Yet ground ambulances have mostly been left out of federal legislation targeting “surprise” medical bills, which happen when out-of-network providers charge more than insurers are willing to pay, leaving patients with the balance.

However, the COVID-19 pandemic has prompted temporary changes that could help some patients. For instance, ambulance services that received federal money from the CARES Act Provider Relief Fund aren’t allowed to charge presumptive or confirmed coronavirus patients the balance remaining on bills after insurance coverage kicks in. Also during the pandemic, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services is letting Medicare pay for ambulance trips to destinations besides hospitals, such as doctors’ offices or urgent care centers equipped to treat recipients’ illnesses or injuries.

But researchers and patient advocates said consumers need more, and lasting, protections.

“You call 911. You need an ambulance. You can’t really shop around for it,” said Christopher Garmon, an assistant professor at the University of Missouri-Kansas City who has studied the issue.

A Health Affairs study, published in April, found 71% of all ambulance rides in 2013-17 for members of one large, national insurance plan involved potential surprise bills. The median out-of-network surprise ground ambulance bill was $450, for a combined impact of $129 million a year.

And a study published last summer in JAMA Internal Medicine found 86% of ambulance rides to ERs — the vast majority by ground ambulances, not helicopters — resulted in out-of-network bills.

Caitlin Donovan, senior director of the National Patient Advocate Foundation in Washington, D.C., said she hears from consumers who get such bills and resolve to call Uber the next time they need to get to the ER. Although experts — and Uber — agree an ambulance is the safest option in an emergency, research out of the University of Kansas found that the Uber ride-sharing service has reduced per-person ambulance use by at least 7%.

Only Ambulance in Town

When Brasfield was rushed to the hospital, her employer, Findlay City Schools, offered insurance plans only from Anthem, and none included the Hanco EMS ambulance service in its network. School system treasurer Michael Barnhart said the district couldn’t insist that Hanco participate. Starting Sept. 1, Barnhart said the school system will have a different insurer, UMR/United Healthcare, but the same plans.

“There is no leverage when they are the only such service around. If it were a particular medical procedure, we could encourage employees to seek another doctor or hospital even if it was further away,” Barnhart said in an email. “But you can’t encourage anyone to use an ambulance service from 50 miles away.”

There is great disagreement about what an ambulance ride is worth.

Brasfield’s insurer paid $347 for her out-of-network ambulance ride. She said Anthem representatives told her that was consistent with in-network rates and Hanco’s $1,206 charge was simply too high.

Jeff Blunt, a spokesperson for Anthem, said that 90% of ambulance companies in Ohio agree to Anthem’s payment rates; Hanco is among the few medical transport providers that don’t participate in its network. He said Anthem reached out to Hanco twice to negotiate a contract but never heard back.

Brasfield sent three letters appealing Anthem’s decision and called Hanco to negotiate the bill down. The companies wouldn’t budge. Hanco sent her a collections notice.

Rob Lawrence of the American Ambulance Association pointed out that nearly three-quarters of the nation’s 14,000 ambulance providers have low transport volumes but need to staff up even when not needed, creating significant overhead. And because of the pandemic, ambulance providers have seen reduced revenue, higher costs and more uncompensated care, the association’s executive director, Maria Bianchi, said in an email.

Officials at Blanchard Valley Health System, which owns Hanco, said Brasfield’s ambulance charge was on par with the national average for this type of medical emergency, in which EMTs started an IV line and set up a heart monitor.

Fair Health, a nonprofit that analyzes billions of medical claims, estimates an ambulance ride costs $408 in-network and $750 out-of-network in Toledo, which is about 50 miles away from Findlay and has several ambulance companies. Even the higher of those two costs is $456 less than Brasfield’s bill.

Widespread Problem, No Action

Similar stories play out across the nation.

Ron Brooks, 72, received two bills of more than $690 each when his wife had to be rushed about 6 miles to a hospital in Inverness, Florida, after two strokes in November 2018. The only ambulance service in the county, Nature Coast EMS, was out-of-network for his insurer, Florida Blue. Neither had responded to requests for comment by publication time. Brooks’ wife died, and it took him months to pay off the bills.

“There should be an exception if there was no other option,” he said.

Sarah Goodwin of Shirley, Massachusetts, got a $3,161 bill after her now-14-year-old daughter was transported from a hospital to another facility about an hour away after a mental health crisis in November. That was the balance after her insurer, Tricare Prime, paid $491 to Vital EMS. Despite reaching out to the ambulance company and her insurer, she received a call from a collection agency.

“I feel bullied,” she said earlier this year. “I don’t plan to pay it.”

Since KHN asked the companies questions about the bill and the pandemic began, she said, she hadn’t gotten any more bills or calls as of late August.

In an emailed response to KHN, Vital EMS spokesperson Tawnya Silloway said the company wouldn’t discuss an individual bill, and added: “We make every effort to take patients out of the middle of billing matters by negotiating with insurance companies in good faith.”

Last year, an initial attempt at federal legislation to ban surprise billing left out ground ambulances. This February, a bill was introduced in the U.S. House that calls for an advisory committee of government officials, patient advocates and representatives of affected industries to study ground ambulance costs. The bill remains pending, without any action since the pandemic began.

In the meantime, consumer advocates suggest patients try to negotiate with their insurers and the ambulance providers.

Michelle Mello, a Stanford University professor who specializes in health law and co-authored the JAMA Internal Medicine study that examined surprise ambulance bills, was able to appeal to her insurer to pay 90% of such a bill she got after a bike accident last year.

That tactic, however, proved futile for Brasfield, the Ohio librarian. She set up a $100-a-month payment plan with Hanco and, eventually, paid off the bill.

From now on, she said, she’ll think twice about taking an ambulance unless she feels her life is in imminent danger. For anything less, she said, she’d ask a relative or friend to drive her to the hospital.

Kaiser Health News (KHN) is a national health policy news service. It is an editorially independent program of the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation which is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

USE OUR CONTENT

This story can be republished for free (details).

from Updates By Dina https://khn.org/news/with-no-legal-guardrails-for-patients-ambulances-drive-surprise-medical-billing/

0 notes

Text

With No Legal Guardrails for Patients, Ambulances Drive Surprise Medical Billing

School librarian Amanda Brasfield bent over to grab her lunch from a small refrigerator and felt her heart begin to race. Even after lying on her office floor and closing her eyes, her heart kept pounding and fluttering in her chest.

The school nurse checked Brasfield’s pulse, found it too fast to count and called 911 for an ambulance. Soon after the May 2018 incident, Brasfield, now 39, got a $1,206 bill for the 4-mile ambulance ride across the northwestern Ohio city of Findlay — more than $300 a mile. And she was on the hook for $859 of it because the only emergency medical service in the city has no contract with the insurance plan she has through her government job.

More than two years later, what was diagnosed as a relatively minor heart rhythm problem hasn’t caused any more health issues for Brasfield, but the bill caused her some heartburn.

“I felt like it was too much,” she said. “I wasn’t dying.”

Brasfield’s predicament is common in the U.S. health care market, where studies show the majority of ambulance rides leave patients saddled with hundreds of dollars in out-of-network medical bills. Yet ground ambulances have mostly been left out of federal legislation targeting “surprise” medical bills, which happen when out-of-network providers charge more than insurers are willing to pay, leaving patients with the balance.

However, the COVID-19 pandemic has prompted temporary changes that could help some patients. For instance, ambulance services that received federal money from the CARES Act Provider Relief Fund aren’t allowed to charge presumptive or confirmed coronavirus patients the balance remaining on bills after insurance coverage kicks in. Also during the pandemic, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services is letting Medicare pay for ambulance trips to destinations besides hospitals, such as doctors’ offices or urgent care centers equipped to treat recipients’ illnesses or injuries.

But researchers and patient advocates said consumers need more, and lasting, protections.

“You call 911. You need an ambulance. You can’t really shop around for it,” said Christopher Garmon, an assistant professor at the University of Missouri-Kansas City who has studied the issue.

A Health Affairs study, published in April, found 71% of all ambulance rides in 2013-17 for members of one large, national insurance plan involved potential surprise bills. The median out-of-network surprise ground ambulance bill was $450, for a combined impact of $129 million a year.

And a study published last summer in JAMA Internal Medicine found 86% of ambulance rides to ERs — the vast majority by ground ambulances, not helicopters — resulted in out-of-network bills.

Caitlin Donovan, senior director of the National Patient Advocate Foundation in Washington, D.C., said she hears from consumers who get such bills and resolve to call Uber the next time they need to get to the ER. Although experts — and Uber — agree an ambulance is the safest option in an emergency, research out of the University of Kansas found that the Uber ride-sharing service has reduced per-person ambulance use by at least 7%.

Only Ambulance in Town

When Brasfield was rushed to the hospital, her employer, Findlay City Schools, offered insurance plans only from Anthem, and none included the Hanco EMS ambulance service in its network. School system treasurer Michael Barnhart said the district couldn’t insist that Hanco participate. Starting Sept. 1, Barnhart said the school system will have a different insurer, UMR/United Healthcare, but the same plans.

“There is no leverage when they are the only such service around. If it were a particular medical procedure, we could encourage employees to seek another doctor or hospital even if it was further away,” Barnhart said in an email. “But you can’t encourage anyone to use an ambulance service from 50 miles away.”

There is great disagreement about what an ambulance ride is worth.

Brasfield’s insurer paid $347 for her out-of-network ambulance ride. She said Anthem representatives told her that was consistent with in-network rates and Hanco’s $1,206 charge was simply too high.

Jeff Blunt, a spokesperson for Anthem, said that 90% of ambulance companies in Ohio agree to Anthem’s payment rates; Hanco is among the few medical transport providers that don’t participate in its network. He said Anthem reached out to Hanco twice to negotiate a contract but never heard back.

Brasfield sent three letters appealing Anthem’s decision and called Hanco to negotiate the bill down. The companies wouldn’t budge. Hanco sent her a collections notice.

Rob Lawrence of the American Ambulance Association pointed out that nearly three-quarters of the nation’s 14,000 ambulance providers have low transport volumes but need to staff up even when not needed, creating significant overhead. And because of the pandemic, ambulance providers have seen reduced revenue, higher costs and more uncompensated care, the association’s executive director, Maria Bianchi, said in an email.

Officials at Blanchard Valley Health System, which owns Hanco, said Brasfield’s ambulance charge was on par with the national average for this type of medical emergency, in which EMTs started an IV line and set up a heart monitor.

Fair Health, a nonprofit that analyzes billions of medical claims, estimates an ambulance ride costs $408 in-network and $750 out-of-network in Toledo, which is about 50 miles away from Findlay and has several ambulance companies. Even the higher of those two costs is $456 less than Brasfield’s bill.

Widespread Problem, No Action

Similar stories play out across the nation.

Ron Brooks, 72, received two bills of more than $690 each when his wife had to be rushed about 6 miles to a hospital in Inverness, Florida, after two strokes in November 2018. The only ambulance service in the county, Nature Coast EMS, was out-of-network for his insurer, Florida Blue. Neither had responded to requests for comment by publication time. Brooks’ wife died, and it took him months to pay off the bills.

“There should be an exception if there was no other option,” he said.

Sarah Goodwin of Shirley, Massachusetts, got a $3,161 bill after her now-14-year-old daughter was transported from a hospital to another facility about an hour away after a mental health crisis in November. That was the balance after her insurer, Tricare Prime, paid $491 to Vital EMS. Despite reaching out to the ambulance company and her insurer, she received a call from a collection agency.

“I feel bullied,” she said earlier this year. “I don’t plan to pay it.”

Since KHN asked the companies questions about the bill and the pandemic began, she said, she hadn’t gotten any more bills or calls as of late August.

In an emailed response to KHN, Vital EMS spokesperson Tawnya Silloway said the company wouldn’t discuss an individual bill, and added: “We make every effort to take patients out of the middle of billing matters by negotiating with insurance companies in good faith.”

Last year, an initial attempt at federal legislation to ban surprise billing left out ground ambulances. This February, a bill was introduced in the U.S. House that calls for an advisory committee of government officials, patient advocates and representatives of affected industries to study ground ambulance costs. The bill remains pending, without any action since the pandemic began.

In the meantime, consumer advocates suggest patients try to negotiate with their insurers and the ambulance providers.

Michelle Mello, a Stanford University professor who specializes in health law and co-authored the JAMA Internal Medicine study that examined surprise ambulance bills, was able to appeal to her insurer to pay 90% of such a bill she got after a bike accident last year.

That tactic, however, proved futile for Brasfield, the Ohio librarian. She set up a $100-a-month payment plan with Hanco and, eventually, paid off the bill.

From now on, she said, she’ll think twice about taking an ambulance unless she feels her life is in imminent danger. For anything less, she said, she’d ask a relative or friend to drive her to the hospital.

Kaiser Health News (KHN) is a national health policy news service. It is an editorially independent program of the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation which is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

USE OUR CONTENT

This story can be republished for free (details).

With No Legal Guardrails for Patients, Ambulances Drive Surprise Medical Billing published first on https://smartdrinkingweb.weebly.com/

0 notes

Text

IRONMAN 70.3 Indian Wells – La Quinta – Race Recap

* A video version of this race recap can be found on my YouTube channel here.

A triathlon is a game of contradiction.

You spend hours, weeks, months training for something that lasts moments of your life. Improve at one sport by mastering three. Train slower to race faster. Race slower to race faster. Do it alone, surrounded by people. Never see a finish line as the end.

One of the most challenging contradictions is the trap of identity. To do well, you have to immerse yourself in training for long periods of time. It can become you; consume you. And then what is objectively a meaningless act of physical exertion assumes a station in your life that it never deserved. And you are left with nothing but finish times and medals, to gather dust because nobody cares.

I thought about these contradictions a lot during my training for my first Ironman 70.3 race in Indian Wells – La Quinta California. It seemed fitting in this vein of contradiction that I would train in the cold and snow in order to race in the warm desert. I hoped that by recognizing the contradictions inherent in what I was doing, I could avoid that most challenging trap, and come away with an experience, rather than just another race.

After Musselman in July, I took a break for a few weeks, and then started training again. I had a few minor injuries, which were challenging, but for the most part my training was consistent. I did some bike fitting and got a set of aerobars on my bike. Winter arrived early in Vermont; we had snow on the ground before Thanksgiving. So most of my riding was indoors. I ran outside as much as I could. And weather doesn’t matter in the pool, of course.

Swimming was a major area of focus for me this fall. I got a second swim analysis and really worked on my technique. I was able to take another ten seconds off my 100-yard time, and by December I was swimming faster on average than I ever had.

I had also been trying to eat smarter, both to be healthier and to drop extra weight. With the help of a friend, I definitely had some success here, though it added some stress to our family routine. Kids like what they like.

I was a little concerned about flying my bike to California, because I had only done it once before and I didn’t have to assemble it myself when I arrived that time. So I broke it down and packed it up at the bike shop so I could get guidance with questions that I had and hands-on help from Darren, my friend who owns Vermont Bicycle Shop. I felt a lot more confident once it was all ready to go.

The flights were pretty uneventful, and we made it to San Diego in one piece — including my bike. One of the first things I did was put it back together; I wanted to make sure I would have enough time to solve any problems that came up. Luckily, there didn’t seem to be any and the assembly went pretty smoothly.

The Catamount, my custom Orbea Terra, ready to ride

We spent a few days with my brother’s family in San Diego, hiking at Torrey Pines and playing on the beach. It was a nice way to get acclimated to the environment. It wasn’t as warm as I thought it would be, but it definitely was a lot warmer than Vermont. Locals on the beach were dressed in winter coats and hats, but our girls thought it was the perfect weather for swimming in the Pacific.

Before long it was time to drive to Indian Wells. The amazing scenery on that drive took us all by surprise. We stopped for a moment but the day before the race was very busy so there wasn’t a lot of time for sight-seeing.

After getting the family settled at the hotel, I had my first Ironman athlete check-in experience and got to see the pro panel, which included the eventual race winners Lionel Sanders and Paula Findlay. I checked my run gear in to T2, a little overwhelmed by the enormity of the transition area. Then it was time for a half-hour drive to the swim start and T1, to see the swim course, check in my bike and decontaminate my wetsuit before hanging it on the racks where it would stay until race morning. I made sure to mark it well so I wouldn’t have any trouble finding it.

My day would have gone quite differently if it hadn’t been for my teammate Lacy. She and her husband gave me a lift to the shuttle buses, which was already a great help by itself, but when she mentioned her water bottles I realized I had forgotten something at the hotel. Specifically, all of my hydration. It was still sitting in my refrigerator. They drove me back so I could retrieve them and I was so grateful. Luckily we were up early enough that it didn’t affect our day — we got on a bus with no waiting and were off to the start area.

I knew the water would be cold. The reported temperature that morning was just under 59 degrees. There was no warm-up swim. We stood in line at the rolling start for a long time before finally getting into the water. And then, finally, after everything, I was racing.

The first one or two hundred meters were tough. I was hyperventilating from the shock of the water temperature and struggling to relax and find my rhythm. I expected that, but it didn’t make it any easier. Finally I settled in, though, and found my zone. It was clear pretty quickly that I should have seeded myself further forward; nobody around me was actually swimming at the pace they lined up for. I was crawling over people all the way. My goggles half-filled with water but I ignored it since I could still see. When I finally crawled out of the lake, I had a personal best time of 34 minutes. By my watch, I had swum ten seconds per 100 yards faster than my first 70.3 in July.

As I mounted my bike, I readied myself mentally to face the biggest contradiction of the day. I had programmed the wattage target my coach and I agreed on into my bike computer, and I was going to stick to that number like superglue. The paradox of my plan was that the number was low. It was lower than I had expected. It was lower than it was at my first 70.3, and it was low relative to my power profile. It was so low that it meant I’d be doing what amounted to a zone 2 ride for the entirety of the bike leg.

The plan was predicated on the knowledge that the course was pancake flat, and that triathlons succeed or fail on the run. We would conserve energy on the bike, allowing my inertia to do most of the work, and hopefully get off the bike with enough in the tank to really drop the hammer.

So what the bike ended up being was a test of patience, rather than fitness. My heart rate stayed low, peaking only at the very start during the excitement of transition and climbing a tiny hill out of transition. I spent a lot of the time focused on avoiding drafting as much as I could, but it was pretty difficult considering that the roads were absolutely packed with riders. That forced me to surge occasionally, but it was okay because the course was so flat.

The first 20 miles flew by so fast that I was actually surprised when I saw the mile marker sign. At 30 miles I felt no worse; very comfortable and just cruising along. It was a strong contrast to my last race, where the 30 mile marker saw me doing pretty solid work. I began to get excited about the paradoxical plan as evidence in its favor continued to build. That naturally inclined me to want to push harder, but I redoubled my efforts to stay focused and in my target zone.

The highlight of the bike course by far was the Thermal Raceway, which is a private racetrack for cars that we got to ride around on. My watts went up on that section for sure, but it was a match that was worth burning. It’s a unique experience to ride your bike around a banked track with perfect pavement, designed for million dollar super cars. I had a lot of fun there.

The rest of the course was technically uphill but the gradient was so gradual, I barely noticed. I rode into T2 just 2 watts over my target. My family was cheering at the dismount line, which was a nice boost going into the start of my run.

After racking my bike and strapping on my running shoes, I started out on the final leg, to see if the contradictions would be resolved. Here I was, running in the heat and sun after training for months in the cold and snow. Here I was, having biked slowly on purpose to see if I could do a faster race. And here I was, after weeks of training at a jog, pushing my legs to go fast, and stay fast.

I have always run fast out of transition, because it takes a mile or two before my legs really feel normal and I can tell how my body is actually doing. At my first 70.3, I slowed that pace after the first aid station, feeling that I would have to conserve energy to make it through the run without shutting down. This day, though, I felt strong. I felt no such impending decline. I felt like I could hold the pace. So I didn’t slow down.

The run followed asphalt roads for a couple of miles before turning off onto a golf course, where it tracked around the greens on a winding, undulating path that was a mix of concrete, dirt and grass. There were no long straightaways, no places to hide from the course. It was highly dynamic and constantly changing.

A conclusion I had drawn from my first 70.3 was that I had been underfueled. This time, I ate and drank everything I could get my hands on during the run. I think I probably ate two or three whole bananas, a half at a time, plus several gels and all the coke, gatorade and red bull I could grab. I didn’t slow down during the aid stations; I didn’t want to lose my inertia. At one point I took a cup of ice, dumped it in my hat and packed it onto my head. The contrasts had never been more stark — at home I had been wearing winter hats to keep the snow off my head; today, I was deliberately packing ice onto my scalp.

It was a two-lap course which meant that I had to run agonizingly close to the finish line at around mile seven, only to have to turn around and do the entire thing one more time. Now I knew what to expect, though, and I knew where to push and where I could relax. Now all I had to do was hold my pace.

When the second lap of the course started to beat me, I focused on my family, waiting for me at the finish, and steeled myself in the resolve to make this all worth it. What was the point of asking so much of them, to support my training, to spend an entire day of our vacation standing around, if I didn’t make it worth it? I wasn’t going to slow down for anything.

The last couple of miles were hard and my pace started to slip a little bit, but I was still moving faster than I had ever really expected. I found my family just before the finish line, gave everybody high-fives, and then took it over the line. It was a personal best by a long margin, with personal records in every part of the race. I almost couldn’t believe it, but there it was.

If there’s one thing I learned from this race experience, it’s that you can’t always see contradictions as obstacles. Sometimes, they are puzzle pieces in a larger pattern that you can’t fully recognize until you’ve put it all together. You can’t always resist the things that don’t make sense; sometimes, you have to lean into them, make them part of your plan and see them through to the end. And that’s when you can find clarity.

We closed out our trip with a drive through Joshua Tree National Park, marveling at the natural beauty of the desert before boarding our plane to fly back into winter. With California behind us, it was time to look forward to a new year, and new contradictions.

Watch the video version of this race recap:

youtube

from WordPress http://www.stevemaas.com/ironman-70-3-indian-wells-la-quinta-race-recap/

0 notes

Text

As Bike Racing Goes Digital, So Does Doping

As Bike Racing Goes Digital, So Does Doping

[ad_1]

Last week, Cyclingnews reported that British Cycling had disqualified its first e-racing national champion, Cameron Jeffers, who not only lost his results but also received a six-month ban (from both e-racing and regular racing) and a fine of £250 ($319 USD). British Cycling’s integrity and compliance director Rod Findlay told Cyclingnews, “Defending fair play in our competitions is at…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Jack Findlay

126 notes

·

View notes

Text

Retrospective Art Show to Benefit NETRF

Oil paintings by artist who died of NET for sale

The Heritage Inn, Sherborn, MA, will host a Retrospective Art Show and final sale of works by late artist, Carl Schaad (1946 – 2011). The three-month exhibit opens with a reception from 5:30 -7:30 pm on September 10, 2019. Approximately 30 oil paintings and 11 giclee limited edition prints created over three decades will be available for sale.

At 64, Schaad succumbed to neuroendocrine cancer. A portion of the proceeds from this retrospective show will benefit the Neuroendocrine Tumor Research Foundation (NETRF).

A well-known Massachusetts painter, Schaad captured landscapes and still life scenes in a subtle color palette. With a strong command of light as a means of conveying emotion, Schaad’s work pulls viewers into the canvas to experience Montalcino’s bell towers ringing, a young boy dipping his toy boat in the waters of Rhode Island’s shore, or a May wind swirling Tuscany’s red poppies. His lyrical craftsmanship creates a meditative mood of ordinary scenes.

He was moved by Impressionists Berthe Morisot and Mary Cassatt. He favored realism and a classical approach leaning toward American Impressionism. Most weekends Schaad could be found painting “en plein air” in rural and coastal settings.

Previous

Next

A decade of mysterious symptoms caused by NETs

Schaad’s neuroendocrine tumor diagnosis was incidental. In 2007, Schaad was hit by an SUV while training for the Italian bike race Giro D’Italia. He was airlifted to hospital with 33 breaks to his ribs, a collapsed lung, and head hematoma. A diagnostic CT scan also found neuroendocrine tumors, which had spread to his liver.

The neuroendocrine tumor diagnosis explained ten years of mysterious symptoms: unexplained stomach cramping and diarrhea, flushing and shortness of breath. Following his diagnosis, he underwent 4 1/2 years of treatment.

A lifelong love of painting

Schaad had an unusual career for an artist. He began seriously painting in his 30s while also working in the corporate world, eventually rising to senior leadership levels at Heidrick & Struggles, a global executive search firm. Throughout his business career, Schaad continued his art studies at The Museum School of Boston, The Art Guild of Boston, and the Ingbretson Atelier. He studied with Robert Cormier, William Bartlett, mentor/friend William Ternes, Joseph McGurl, and Mary Minifie.

At age 55, he left the corporate world to paint full time. Finally able to follow his passion, he was sculpting beautiful images with paint. He was represented by The Wally Findlay Gallery, in NYC, Chicago and Palm Beach; J. Todd Gallery in Wellesley; and The Christina Gallery on Martha’s Vineyard.

In Carl’s memory, the Schaad family will be donating a portion of the proceeds of this retrospective show and sale to the Neuroendocrine Tumor Research Foundation. They hope to help others by funding much-needed research for a cure and raising awareness about confusing symptoms that are often misdiagnosed.

The post Retrospective Art Show to Benefit NETRF appeared first on NETRF.

https://ift.tt/2kdCCTU

from WordPress https://netrf.wordpress.com/2019/07/16/retrospective-art-show-to-benefit-netrf/

0 notes

Text

New Post has been published on Superbike News

New Post has been published on https://superbike-news.co.uk/wordpress/suzuki-voted-best-manufacturer-feature-at-motorcycle-live-for-second-year-in-a-row/

Suzuki voted best manufacturer feature at Motorcycle Live for second year in a row

Suzuki’s restoration of the G-54 – the precursor to the iconic RG500 Grand Prix machine – at Motorcycle Live 2018 has been voted as the best manufacturer feature at the annual motorcycle show, the second time Suzuki has won the award in as many years.

The bike was restored to working order by former Grand Prix technician Nigel Everett with the help of Suzuki’s Vintage Parts Programme. There was also assistance from Barry Sheene’s former technician Martyn Ogborne on weekends.

Positioned not only so visitors could get a closer look at it, but the bike was also fired into life at various points during the event, allowing enthusiasts to see it in the metal and also revel in the sounds and smells of the legendary two-stroke machine. Paul Smart, who raced the bike in 1974, was also present to talk about his experiences.

Suzuki GB aftersales co-ordinator, Tim Davies, who organised the live build said, “We’ve done a few builds and restorations in recent years at Motorcycle Live, but this is probably one of the most interesting because of the story that comes with the bike. When we learned about it and talked about bringing it back to life we were all really excited about the prospect. That’s when we thought, ‘if we’re this excited, hopefully other motorcycle enthusiasts will be too’. So we made the decision to bring it to Motorcycle Live so everyone else could enjoy seeing and hearing it restored to its former glory, and we’re really pleased to learn that it was appreciated by the visitors.”

The G-54 concept was born in May 1973 as Suzuki prepared to return to Grand Prix racing in the premier class, five years after withdrawing following regulation changes by the F.I.M.

The bike – where G denoted Grand Prix use only and 54 stood for 1974 – was designed and built under the stewardship of Makoto Hase and Makoto Suzuki, who had previously been tasked with converting the GT250, GT500, and GT750 machines into the TR250, TR500, and TR750 race bikes.

Barry Sheene got his first taste of the machine in November 1973, but to help keep the weight down the G-54 employed an open cradle chassis with no lower chassis rails beneath the engine. However, despite finishing second in its first ever Grand Prix at Clermont-Ferrand in April with Sheene aboard, by June the chassis had been replaced with a conventional double cradle design. It was raced by Sheene, Smart, and Jack Findlay that year.

The award is decided purely by public vote with no input from organisers or the Motorcycle Live show committee, which only adds to Suzuki’s delight in knowing it has bought pleasure to the motorcycling community.

For more information on Suzuki’s Vintage Parts Programme and Suzuki’s range of motorcycles, click here.

Watch the bike fired into life at Motorcycle Live here.

Industry News Gallery

jQuery(document).ready(function($) if(typeof(gg_galleria_init) == "function") gg_galleria_show("#5c545588109b5");gg_galleria_init("#5c545588109b5"););

Grid Girls Gallery by Grid Girls UK

jQuery(document).ready(function($) if(typeof(gg_galleria_init) == "function") gg_galleria_show("#5c5455881528f");gg_galleria_init("#5c5455881528f"););

[vc_row][vc_column]

@gridgirls

14.6k Followers

Follow

[/vc_column][/vc_row]

0 notes

Text

Jack Findlay

#motorcycle#jack findlay#motolegends#sport bike#racing#motorsports#ride hard or go home#built for speed#experience speed#classic motorcycle#please reblog#moto love#lifestyle

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jack Findlay

#motorcycle#jack findlay#motolegends#sport bike#racing#motorsports#ride hard or go home#built for speed#classic motorcycle#moto love#lifestyle

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jack Findlay.

Jada 500.

25 notes

·

View notes