#feanorianweek18

Photo

Day three: Celegorm for @feanorianweek. Spent more time on it, so I’m much more happy with this one

#feanorianweek18#feanorianweek#celegorm#plus his better half#and curufin#watercolor#micron#myart#not my character#tolkien#silmarillion

116 notes

·

View notes

Photo

✨Tiny pastel Fëanorians collection✨ for @feanorianweek

💜Day 4- Caranthir💜

91 notes

·

View notes

Text

Departing

Set in the scene in The Two Towers movie where the elves are leaving Rivendell. The idea of Elrond and his people heading for Valinor right at the critical moment, when the fate of Middle-Earth would be decided in battle, always made me mad. I figured Maglor would be angry about it too.

Lanterns glowed in Imaldris’s dark streets. The city’s elves, cloaked in blue-gray, made a solemn funeral procession towards the gate.

Elrond closed the door of his office behind him. He likely wouldn’t enter that room again. He walked along the raised hallway, in no hurry to leave forever the place he had built so long ago,. Even though the sides of the hall had, in lieu of windows, open archways, Elrond could hear no noise from the procession.

Footsteps, soft but distinct, came up the stairs and into the walkway. An elf strode in, his seething visage utterly out of place among the serene procession.

“You’re going,” he accused.

“We are weary of this world. It is our time.” Elrond kept his face expressionless.

“In the heat of war?”

“My people leave--”

“You do not leave,” the elf hissed, “you flee. When all seems lost, the elves decamp for paradise while the shadow engulfs Middle-Earth.” Every syllable mocked the Lord of Rivendell.

Elrond halted but did not speak.

“Gondor and Rohan are weak on their own. They need your aid.”

“We have no aid to give!”

“Four hundred trained elves, is that nothing? If the free armies unite all at once, they could defeat Sauron. You know that. If the armies do not unite, he will beat them each separately.”

“Cirdan is waiting for us,” Elrond’s voice was cold.

“Let him wait! Will you have this be the last stand of the Noldor?”

The elf spun and swept back the way he came. But just before he descended the stairs, he half-turned and said, “When you reach Aman, there will be no peace. There will be only the guilt of the lives you could have preserved.”

“Ada,” began Elrond, but his voice trailed off into an exhale. He continued on his way out.

#feanorianweek18#no tw#it felt wrong to not post something for the character i named my blog after#maglor#feanorian#silmarillion#fanfiction#lotr#elrond#elves#rivendell#tolkien

88 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Day 6: Ambarussa, for @feanorianweek <3

Twins and childhood. I think they had some very great times together, and that they’d sometimes go out to watch the moon and talk about how their day was.

79 notes

·

View notes

Text

He’d been looking forward to this moment for a year now – well, longer really, but that had been in the abstract sense of a hope, not in the certainty that it would happen – and now that it has finally come, Curufinwë felt like his heart might burst from the incandescent joy of it.

His son.

He was holding his son.

The baby was absolutely perfect in every respect, down to the tiny nails at the end of each delicate finger and toe.

For the first time since they were wed, Tyelpesilmë’s regard felt pale and distant compared to the urgent immediacy of the incredible little being in his arms, blinking back at him with the not-quite-focused eyes of the newly born.

It is only after several minutes – though they might well be hours or possibly even days, he knew himself prone to lose track of time when absorbed in anything, and he’s never been so wholly absorbed in anything else in his entire life – that it occurred to him that he’s responsible not only for nurturing, protecting, and loving this child.

He has to name his son.

It’s not something he’s given much thought to before, but now that he did, his stomach is tying itself into knots.

He’d been intensely proud as a child to be the son Fëanaro bestowed his own father-name upon. It was only as he grew that he began to see that wasn’t always such a wonderful thing. With a name like Curufinwë, much was expected of him – by his father not the least.

Sometimes he’d basked in that, but more often, it had been a weight. If he lived up to expectations, well, they’d expected it of him, hadn’t they? If he failed to match his father, though, it was worse – the whispers, the sympathy (both real and feigned), and the disappointment. Not to mention, Finwë’s eldest son excelled at so much that it was difficult to find something he’d not tried his hand at, something Curufinwë could call his own.

As such, passing the name on to a child was absolutely out of the question. Two Curufinwës was already more than enough. Come to that, he didn’t much care to bestow a -finwë name either, even if it would probably generate immense satisfaction or amusement in various quarters if Fëanaro’s favorite son contradicted his naming of the twins.

“What, my silver-tongued husband for once without words?” Silmë asked.

Though her words were playful, there was a thread of mingled pride and love in her spirit as she cast her mind toward his.

I think we have made something even your father cannot find fault with, she added.

His father had better not find fault with their son!

“What are you going to call him?”

Curufinwë blinked. He had been hoping to have a bit more time before anyone asked, to think, to choose something exactly right, and above all, something all the child’s own.

He had the sudden conviction that his son will not be one of a row of anything, be it -finwës, -kanos, or -aratos. It’s one thing to have a theme, it’s another to recycle elements for every child, as if they don’t each deserve consideration of their own.

As one of the first in his generation to beget a child – he’s still not quite sure how Angarato had beaten his older brothers and cousins to the punch – he had the happy opportunity to set a new trend in the family – to give each child he begets a unique name, one that will be entirely theirs to shape.

But he could not take too much time over the decision. It was not unusual for a mother-name to be given years after the birth, unless the mother had a glimpse of foresight at the time the child came into the light.

He gazed down at his son, now reaching enthusiastically for Silmë’s hair. The child caught a handful of her long silver tresses, and then gazed in perplexity from one hand to the other, bemused by the difference. It was clear, however, which he preferred…

“Tyelperinquar.”

The silver-fist. As a hope that he will find joy in the craft as we do, and as a reminder that you are dear to us both.

He thinks the name fits, and their son smiles as they both call him by it.

77 notes

·

View notes

Text

Abundance (Nerdanel) - Fëanorian Week 2018

For @feanorianweek Yes, I am early for Nerdanel day.

Read or comment on Ao3 here.

Summary: Of artistry, women's bodies, and loss.

I. Journeyman

On a summer day, she began the work that would become the most famous of all the creations of her hands— except for one.

It began as if from nowhere (or so it seemed to her at the time).

True, by then she had spent many years as her father’s apprentice, praised for her skill and her industry, her patience and her delicate touch in shaping surfaces.

Also true, that when she had turned from forge work to creating likenesses— when she had found her own proper gift in sculpting the faces and forms of her people, and of the living animals and growing things— then she had begun to win great praise. Then the Noldor rejoiced in her work, and passed her figurines from hand to hand, and set them upon pedestals and hearth-mantels.

They began to say that Mahtan’s daughter had his spirit in her fingertips. A few, even, whispered that now they understood how she had caught the eye of the prince, her father’s master student (thought they managed to sound as if it were Fëanor’s achievement, discovering her hidden worth, more than it were her own merit for having it).

But this new work: this was different.

She had returned upon the eve of summer from a long ride at Fëanor’s side in the distant wild edges of Aman. There lay in her studio an enormous length of wood, hard, dense and richly colored, with a scent redolent of warm far-off forests far to the south. It was the huge bole of a mighty tree, split and stripped and dried, and brought here as a gift by a travelling friend of her father’s.

Till now she had had no idea what to do with it.

But on this day, with the golden treelight just rising, and the air promising summer heat to come yet still slightly chill, so that she had wrapped an old shawl about her shoulders when she came out to her workshop—

On this day, she took up her tools and began to carve, and worked as she had never worked before. With axe and adze, she roughed out the form that took shape in her thoughts. Before the light changed, a great figure had begun to spring forth from the wood, as if it— as if she — had always been there.

Yavanna strode forth, in the woman’s body in which she cloaked herself in Eä. In Nerdanel’s shaping, the noble body, twice as tall as an Elf, walked amidst her meadows, a long robe in graceful carven folds swirling after her, which yet did not obscure the curve of a mighty hip, the generosity and delicacy of her broad bare bosom, the merry roundness of the belly, the vulnerable, powerful cleft between her legs. Her curling hair flowed in a river over her shoulders, with flowers all among her endless, wild locks.

Nerdanel’s own cloak had long been dropped into the sawdust and shavings on the floor; her red hair was damp and tangled with sweat; her arms ached. She was half aware of sending several people away with abrupt words, when they intruded into the corner of her vision. Water was left at her elbow, and she drank it; bread, and she put it into her mouth. But she did not cease.

When nightfall came for second time, her mother came and urged her to take rest; and sometime later, Mahtan followed. He watched his daughter at her work in silence for some time, without comment; and then at last said, “Not as your father, and no more as your master, do I speak: but as your fellow artist. Only you may say how the hours of your inspiration run: when to take up and when to cease. But you are making my wife, your lady mother, worried.”

Abashed, Nerdanel laid down her tools at last, and went into the house, and embraced her mother, and her father too, and allowed them to bring her food and send her to the bath and bed. But the next day she rose early and fell at once to work, and the next, and the next.

After some weeks, the as yet-nameless work had grown in size till it stretched for many yards down the enormous slab of hardwood. She had begun in the very middle, with the centering figure of Yavanna. Now on either side, as if emerging from the wood in the Vala’s wake, were laughing maidens and youths with their arms full of fruit, were tree boughs swaying laden with blossom, and meadows full of ragged wildflowers. With chisel and mallet she refined each figure in minute detail; hollowing the space between until the figures seemed all but ready to leap from the background. Deer paused among the shadows of the woodland, shy and fleet. Small plump birds cocked their tiny heads and gave a sideways look. Rabbits ran among tall grass, throwing up their hind legs in saucy pride at their speed.

At some point, Nerdanel realized that Fëanor was standing in the studio; his arms folded and his gaze intent. She had not seen him in — some time, and yet: he was in everything, in all of this. He gave her a very small smile and cocked an eyebrow at her. She did not say, “I am working; I must do this; this is the best thing I have ever made, and it is the most important thing right now.” For she saw that he saw; it was one of the reasons she loved him.

She went back to work, and he went away. But he came again and he brought with him apprentices carrying many trays and vessels. “I had an idea,” he said gruffly. “It is an experiment. You need only use them if you like!”

The workmen set their trays on the side table, and wiping the sweat from her brow, she came to gaze at the array of bowls and jars before her. Colors in dense, rich liquids, opaque as milk, were found in some jars. Red ochre she recognized, and yellow orpiment — but here were shades of pigment she had never seen in any artists’ work, even among the most cunning Noldor artisans. In one jar, gold was made liquid. Scarlet bright as winter berries pooled in another, while a blue as of a living iris-flower filled its neighbor. Yet again, a translucent glaze like the delicate skin of wrist wherein the blood gives faint color to the surface. Beside this, in other samples, rich powders of crushed crystalline minerals glistened; when mixed with oil, they smeared into a hundred subtle gradients.

Delight swelled within her.

Fëanor was talking now, half nervously: “The greens and blue were difficult: that one is copper acetate, and that one, azurite — you must wear gloves, and mind you do not bite your brushes —”

She threw her arms around him, tucking her head into his muscular neck, and he fell quiet. She took in his scent: chemical buzz of the laboratory and warm work damp of his skin and ash of the fire and the good plain linen of his work-robe. She held him tightly, saying little, but she felt his heart beating within his broad chest. Soon she returned to her work, but Fëanor went smiling when he left.

The great sculpture went on towards its final form. Now Yavanna’s cloak in its swirling folds was edged with gold, and the silver stars sprinkled on it were picked out against a background of deepest blue. Now each fruit was touched with glistening red, or bright yellow tinged with green, or wine-dark purple, and tree-blossoms were dressed in frothy white just tinged with pink.

She had a brush in her hand — sable fur, just freshly dipped in gold flake— touching the tracery of jewels around the neck of a dancing handmaiden — on the day that Mahtan came to her and said, “Aulë has come to our house, daughter.”

Of course she gave it to them, to Aulë and Yavanna, without their need to ask. In all the time of working on it, she had never stopped to think what or who it was for, only that it come to be. And the Giver of Fruits and the Smith set it up in a great plinth amid her own meadows, the ever-verdant gardens of the Kementari, where it could be visited by all who came that way. Often in the days of festivals, the Elves would come and raise their voices in song at this place, and children would run and play near it and shyly touch the wooden figures in their lifelike joy.

In later years, Nerdanel was to make statues of all — of most — of the Valar, as well as of the famous and the great among all the Eldar kind. She worked in those later eras in many noble materials — marble and bronze, truesilver and alabaster, ivory and basalt — for wood came to seem a material rather humble for the splendors of Aman at its noontide.

And yet the image of Kementari, Queen of Earth’s flowering, made in the very freshness of Nerdanel’s heart in its first youth, remained her most famous and beloved work for many a long age.

II. Innovation

Down at her waist, right over each hip, nodes of a curious warm tenderness bloomed, almost but not quite painful. Her breasts grew sensitive to the touch: they felt as they were swelling, like buds on the tip of a branch in springtime. Even her walk changed, she felt: It was far too early for any real weight to belong to the small form inside her, and yet she planted her feet differently, as if she carried in her hands a vessel that she must not spill.

Many months later, when her time drew near, her belly swelled out before her like a ship in sail; her back ached, and other parts, and it was wearisome to sleep or to rise from sitting. Sometimes cramps and pains ran through her like a hot knife: her own body stretching and rolling in its new, unpracticed art, in which her own self was the material from which an experiment was shaped. Inside her the coming child moved and shifted, a stranger and yet an utterly known and familiar companion.

Despite these ills, never had she felt as strong: she was as full of satisfaction as a feast-cup overflowing with wine. At her side Fëanor was both joyful and tense, prideful to the point of arrogance about his coming fatherhood, and strangely timid as he touched her rounded belly. He ran to fetch her tea, a silken cushion, sandals when she would walk: shouted at the servants to quiet the least sound of their work; came back again and again to the house from his own workroom, still smeared with soot, to see if she were well.

Her mother took her to the warm springs to rest in the water, on a time. There came suddenly about them the feeling of awe and strangeness that presaged the goings of the Valar. Suddenly, Estë and Irmo were there among the Elves who bathed amid the mossy rocks, and their attendant Maia with them. The mists of the hot springs swirled into shapes of half-seen winged forms and ghostly hands, which caressed the two tall beings as they passed, and faint silvery bells and sighing chants were heard as if at a great distance.

With gentle hands, Estë reached down to Nerdanel from her own great height, and touched her shoulders and then her swollen belly. At once, her aches and tiredness lifted, and she felt the child within her leap and play as if in response. And Nerdanel to her surprise saw that there was a sort of wonder in on the strange, fair face of Estë, who reached out a hand in turn to Irmo beside her. With a look of sorrow, the Lady of Healing said to her spouse, “But this pain to come — must it truly be so?”

The Lord of Dreams, as ever, walked with with his face shrouded in shadows under his deep hood. If he shared his lady’s emotion, they could not see it. But he bowed his head and answered in his strange cold voice: “So it is with the gifts of Ilúvatar in Arda marred. Great works are achieved through pain and labor proportionate to their excellence; and abundance creates the potential of absence, as an object brings with it its own shadow.”

When they had gone away, Nerdanel said this aloud to her mother, surprised: “Surely Estë has seen many Eldar bear their children, in the ages since we came came to Valinor, and knows the workings of our bodies? The pangs of childbirth are hard, you all say, but I am strong and ready!”

“You see,” said Nerdanel’s mother, whose face was troubled: “They do not themselves give birth. Bodies are as garments to them: a thing which may be cast off or altered, and are not in essence themselves. And seeing children is not like having them. They who have always been, and always will be, how can they understand what our children mean to us?”

“I suppose,” said Nerdanel, musing,”we Eldar are like unto their children, in some senses.”

“It is not the same,” said her mother with finality.

Soon after, Nerdanel’s labor began: the pangs that tore a shout from her, the gush of fluid and blood, the hours-long striving that drenched her in sweat and made her grind her teeth and clutch her mother’s hand. And then in her arms and Fëanor’s, at last the small, warm, and well-made child, a fine red-gold down on his head: he peered at their faces with enormous eyes, his spirit reaching out wordlessly, instinctively, to touch their own.

“Look what we have made!” she said to Fëanor.

III. Masterpiece

On the road between Tirion and Valmar, there was an unlovely place where the road passed through a narrow, rocky valley.

On a morning when the heat of the Sun beat down and the air was like the fiery breath of a forge door opened, she took her chisel and began to carve.

Week after week, she worked at it. Her hands were worn and bruised, the skin dry and cracked with stone dust, her nails broken. Her boots and leggings were covered in a thick paste of slurry, and even her tunic and other clothes were frankly unclean. Her hair was stuffed carelessly into a rough cap, from which it escaped in ragged ends.

Figure after figure, body after body, began to take form.

She made no portraits: scrupulously, she did not shape the image of a warrior one-handed; or single out a figure with a harp or a hunting hound; she did not make a king with a seven-pointed star on his armor, a son beside him as like as a young tree to a mighty oak; she did not add a pair of twins.

It was not her own emptiness alone that she made visible.

First, she carved a file of tall warriors with high-crowned helms and swords in their hands; grim faces, glimpsed beneath, fell and fair. And at the feet of the striving warriors, other figures, fallen; pierced, dying, broken.

But she was not done.

Dark forests of trees twisted and infected she carved, and between their rotten trunks the figures of swollen spiders and slinking wolves. And she did not forbear to add amidst them torn and twisted bodies, dragged away as prey.

But she was not done.

Out of the rock she brought forth the images of Morgoth’s thralls: their bodies attenuated to near-skeletal thinness, loaded with chains, surrounded by leering, monstrous guards, who mounted with triumphant lust over dishevelled captives.

Rivers of flowing fire rolled down from grim mountaintops. Fell winged monsters sped aloft. Fragmented skulls and the shattered bones of once-lovely bodies were scattered before broken towers.

Nerdanel had never seen the Aftercomers, the Children of Men, or Aulë’s people, the skilfull Khazâd, but she used her artist’s eye to guide her hand. Her tools worked out the shapes: there in stone the younger peoples fought their hopeless war against the Imprisoner, amid a sea of raging foes. Little villages burnt away, and helpless beasts of the field ran distraught, and children raised their hands to an empty sky.

On a time, her father came to her. “Daughter,” said Mahtan. “What are you doing?

“They said,” Nerdanel replied. “That this land of bliss has been fenced against those across the seas, so that even the echoes of the Noldor’s lamentation should not come to our ears. And so they raised up the mountains to these terrible heights, and set their nets of dark enchanted seas to bar all comers. They call me the Wise, and yet I am confounded: for it seems to me, Father, that they have walled out repentance, if it comes, as well as guilt — and shut out as well the screams of those who never saw a Silmaril as effectively as those who went forth to avenge Finwë.”

She threw down the weighted hammer she had in her grasp, and wiped her dusty hands on her cloak.

“But there are tears and cries of anguish closer than Middle-earth, if They have not stopped their ears. You know as well as I the dark tidings that have reached us, ever bloodier as the centuries pass. Would you know what I see of my sons in my tormented dreams? The great towering mountains do not keep those out!” Her father made a sorrowing gesture, as if he would bid her to peace, but she clenched her fists defiantly. “Praise I was given — I did not ask for it — because I did not join in Fëanor’s rash rebellion, because I bid patience to my people to wait on the Valar’s acts when we were foundering in a sea of dark that Morgoth created. I would ask you: how was that patience rewarded? If the Valar do not like my grieving — well, I would remind them that they were not the givers of all I have lost.”

She took up a fresh sharp chisel. “I ask nothing of Them, but that if They pass by, They may look — or close their eyes, if They will. Some are skilled at that, methinks.”

Mahtan went sadly away.

At first she labored alone. And then one day, she found some women standing in a knot behind her on the edge of the road, looking upward. Ladies of the Noldor: once she had known them, though not well, when all her own hours were overflowing with children and mate and her art.

There stood a tall matron whose own husband had gone with Fëanor: and with them went her sister and brother, also. She lived now all alone in a tall white house, where a single lamplit room was visible in the evenings to passersby.

There was another, a fierce politician and mistress of a weaving-guild, who had been a partisan of Fingolfin. Yet she had stayed behind, a tiny babe clasped in her arms, when her haughty grown sons had marched out of Tirion with their father. It was whispered that her spouse and children alike had been shades in the halls of Mandos before ever the new Sun rose, dead among the salt waves of Acqualonde or on the grinding ice of the crossing.

Others there were, both young and ancient, all soberly cloaked and solemn. And one came forward bearing a lamp and said to Nerdanel, “Sister, the shadows grow long here, and your eyes must be weary. Let me light your work.” Another lady came with a jug in her hands and begged her to ease herself with a draught of wine. Yet another, a brawny maid with the arms of a smith said, “Mayhap you do not remember me. I was in Mahtan’s shop when you were a little red-haired thing still playing at carving with an apple. An you give me the task, I would help you with the rougher work.”

Father and brothers, sons and nephews: men came too, mostly Noldor: and they spoke or sang of the brothers and sisters, the betrothed maid or the the beloved student, who had rebelled and gone into Exile unrelenting with their Kings and lords. And even, to her shock, there came a few from Olwë’s people. “We have not forgotten Alqualondë,” they said grimly. “But what of our kin and cousins long parted? What of the Woodland Elves who tarried on the journey, or lingered in the ancient forests east of the Ocean, or cling to the last seaside havens of its shores?” And so she added these, too, to the unfolding tale of stone.

And so the work went on faster.

And one day, they came. Yavanna as she paced slowly down the road had a crown of winter thorns in her hair, and a sober robe as of snow; Aulë had his great golden beard and long locks closely bound, and had put off the beautiful jewelry of craft and wonder that once he had rejoiced in.

The crowd of Elven men and women moved quietly aside, as the Vala approached.

Yavanna ran her hands over the stony trees of the sorrowful forests, and touched the carven forms of children amid their ruined homes. Aulë, his brow drawn, put a great work-roughened finger to the place where she had shown small, brawny warriors, beards flowing, as they lifted carven axes in defiance. They both lingered over the panel in which she showed a fallen king in the dark pit, torn by wolves, and a pair of lovers bravely striving to overcome a cruel foe amid the broken world.

And they turned to her with sorrow and sympathy in their eyes.

“Someone is coming,” said Yavanna. “He is on the road even now. The salt wind of the wide ocean stains his cloak, still, but now the white dust of Aman gathers on his shoes as he treads the empty highway to Valmar. And in his hand he bears a treasure that you know of old — for in your home dwelt he who made it.”

Her heart raced, and she turned to them with a question in her eyes. The Great Smith saw it, and shook his head. “He who bears the Silmaril is a stranger, in more ways than one. Alone among all the mortals of the world he has been permitted to alight on our shores. Out of love for all the Children of Iluvatar, the Eldar and Men, he has come to call out pity and aid from the Lords of the West.”

“The world is changing, and a new era dawning,” Yavanna followed in her sweet ringing tones. “The cry shall be heard at last: for pity, pardon for the exiles, and succor beyond hope for those who suffer in the darkened lands, ere Morgoth ascends to final and lasting victory over all. And it will be given! War against the Enemy who has despoiled the world — it is coming!”

Then Aulë said, with pity softening his craggy looks: “But lady, the tale is not yet all told. For I foresee that this jewel that comes back across the sea is the only one of the Three that shall ever come here. But of those who were your own treasures, they have soiled their claim in blood unjustly shed, falling from noble war against the Enemy to needless crimes against their own kin. A choice still lies before the few who remain, ere the close; to choose a path of repentance or despair. But a dark cloud lies over their end, and little hope, I ween. My guess is that none of your own shall come among us again, unless first they pass through death and the halls of Mandos and win release. And maybe that will not be until the world is remade.”

Yavanna had tears in her eyes, and on her sun-burnt cheek. “Perhaps it would have been more merciful to you if such sons had never been, then the fates to which they have come. To have them and to lose them all, ending in such evil downfalls: perhaps it is worse than never having — “

“No,” said the sculptor with finality. “Would you rather your Trees had never lived? Or that they grew, and once were happy, but were destroyed? And it is not for myself alone that I have been laboring. A million mother and fathers have lost their sons and daughters since Morgoth passed over the seas. And all is all: if a mother had only a single child, and lost them, then she has lost her whole joy, as much as I who have lost seven. My poor Fëanor could not bear it — to make and to love and to lose. But love in full brings with it the risk of losing and parting, as all things in the world cast their own shadow.”

She swiped a grimy hand across her cheek: ”If something is to be done about all this, at the last — good. Now I will finish.”

Then Nerdanel put down her tools and rested.

Link on Ao3 here. Comments and feedback loved and welcomed. And sharing!

#feanorianweek#feanorianweek18#Nerdanel#silmarillion#birth is messy#creation is messy#bodies#motherhood#blood#dirt#art

57 notes

·

View notes

Text

Long live the King

@feanorianweek day 1 (March 19th) – Maedhros-> childhood, kingship, torture, adjusting/coping, unity, beauty

His father was dead. Fëanor’s last words of curse for Morgoth still echoed in the mountains and valleys bellow. Where not a minute ago there had been the proud High King of the Noldor in a puddle of his own blood now there was only a pile of dark wet ashes. Maitimo couldn’t do anything but stare at them. His father, greatest of their people, leader of thousands. Dead.

In the back of his mind he registered his brothers’ reactions around him.

Kurvo howled louder than storming winds, raw and guttural and, oh, so terrible. Tyelko and Moryo were trying to hold their younger brother still, though they were in no better shape themselves. Tyelko was sobbing -making sounds nigh whimpering- with his arms thrown over the other two, whereas Moryo panted hard, eyes glazed with building up tears as he attempted to speak their brother calm but all that came from his lips was Kurvo’s name.

A few steps behind them stood Pityo, still as stone. His face was the shade of his hair and a vain stood out on his temple. There was a weird pull on his mouth, something ugly between a grimace and a smile. A single tear tricked down his right cheek.

Lastly Maitimo looked ahead, where Makalaure had crunched on their father’s left side and clutched his hand. His position hadn’t change, still holding out his hand for the one that had forged him his first flute but was now gone. There was some of the ashes on Kano’s fingers. Maitimo felt sick. With dread he raised his head to meet the eyes of his brother. The once gleeful minstrel of their family was staring back at him with dead eyes and rivers of tears marking his soft red cheeks that just seemed to flow non-stop. “The King is dead” Kano murmured with his mithril voice hoarse and creaked.

Looking at so much emotion in his family, Maitimo felt an outsider. He felt no rage, no pain or grief, not even the cold-blooded relief on Pityo’s eyes. He felt nothing. Only numbness.

“The King is dead!” Yelled a voiced behind him, filled with horror. Until then Maitimo hadn’t realized that some of their soldiers had made their way to the scene.

The cry was echoed by the mountains and their people alike. A soft breeze ruffled Maitimo’s long hair, waving it like a red flag.

The King was dead. His father was dead. Maitimo was left adrift.

“Long live the King!”

Those for words ran like a drum against his ears.

Right. He was the eldest. Fëanor’s firstborn. Nelyafinwë, his father named him, meant to be his disregard of Nolofinwë’s position. Third Finwë. And indeed the third king he would be. Left to care for his grieving brothers, to guide their people in this unknown lands, to fulfill their oath.

Far away were the bright days spent by the river with Finno, when they couldn’t care less for what was expected of them as firstborns of their Houses. When the differences between their families were not greater than the difference in color of their hair. When they had laughed together, and played together, and being together as one. Alas, he missed his beloved cousin now more than ever, their sundering another parting gift of his father.

What was he to do?

“Long live the King”

Makalaure’s words were a mere whisper somewhat heard above the thundering wind.

As one all his brothers dropped to their knees, finally overwhelmed by the truth. It was not a display of respect or submission, Maitimo knew. It was a plea to their big brother. The blunt force of their father’s passing hit them at full force. Everything was wrong, and they needed him to make it right again. They needed him to put the pieces of their family back together.

Kano was still looking at him with his wide grey eyes flooded. Maitimo reached out to him, wiping the ashes from his trembling hand and giving it a tight squeeze.

He had never once let his baby brothers down. He didn’t intend on starting now.

#yay!! 😄😄 finallyh#feanorianweek#isfinallyhere#maedhros#mae#mae is ma bea#angsty#feanorians#kingship#cliche tittle is cliche#feanorianweek18

54 notes

·

View notes

Photo

hunter of Oromë for @feanorianweek day 3 🌙

#mine#my art#queenie's art#art#feanorian week#feanorianweek#feanorian week 2018#feanorianweek18#celegorm#turcafinwe#tyelkormo#silmarillion#the silmarillion#the silm#feanorians#tolkien#elves

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

Feanorian week, day 2: Maglor

(AO3 link) (Day 1: Maedhros)

@feanorianweek

Tenn’ ambar-metta

Unto world’s end

Unto world’s end!

they swore, and he drew his sword

as did all of his brothers

and flames illuminated their faces

what an enchanting tale

painted in the colours

of a nightmare

how frightening they were!

why?

they marched in their father’s steps

and their name

became a hated and cursed one

Ah! the everlasting Darkness

was it not already upon them?

and unto world’s end

they fought against all – friends and foes

fighting fire with fire

what an epic tale

drenched in blood and sorrow

betrayal

and he slew too – he had sworn

no matter how awful their deeds were

he took part in them all

and death forsake him!

Unto world’s end

he sang, alone, under the night sky

never to forget

but maybe

but maybe…

something else was there for them

among ruins and desolation

hidden in the corner of their desperation

born from fire and sadness

two children; abandoned

(because of them!)

with eyes as sad as his

Could he find repentance

and peace

if he opened his arms to them?

Oh, but they had sworn

Unto world’s end!

was he to break his oath

and betray his last brother?

(how strong he was!

broken but faithful still!)

He did not fear everlasting Darkness

no

they never left him since that night

of blood and fire

they haunted his mind

and engraved themselves in his steps

no, he did not fear them

and yet…

How could he claim

to see right from the wrong

when his hands had bathed in blood?

and unto world’s end

they kept their oath

but sadly

but sadly…

they should have sought redemption

and the sweet embrace of forgiveness

instead of throwing themselves to the fire

and burn their mind to madness

He had kept his oath!

against all, he had kept it

and he hated it! he hated it!

Away from this curse!

Oh, cruel gods, can you not set him free?

and the sea accepted his gift

and the waves sang with him

How their world ended by their own hands

Nothingness.

#feanorianweek#feanorianweek18#maglor#the silmarillion#my stuff#my writing#(why did tumblr auto-corrected maglor as batman ????)

24 notes

·

View notes

Photo

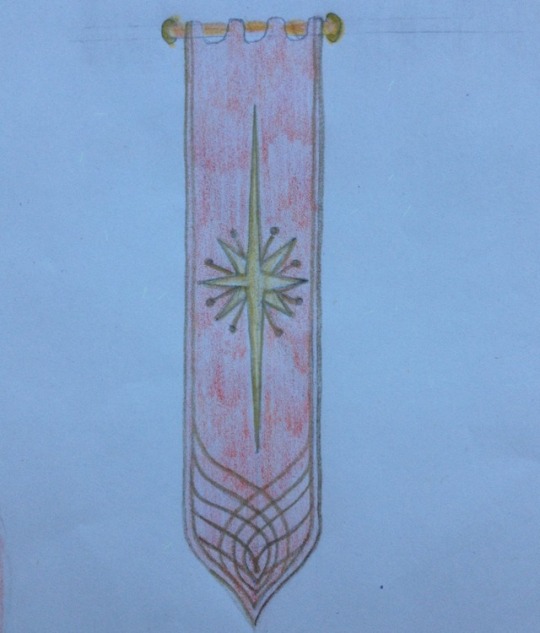

My tribute to Maedhros’ day of Fëanorian Week. The banner is one of a design that would decorate the halls of Himring, not one that would have “assailed the enemy in the rear” (Tolkien, the Silmarillion, Of the Fifth Battle). It is supposed to be blood-red with golden embroidery, my pencils didn’t really cooperate, but anyway.

Thanks to @feanorianweek for organising the, of course, Fëanorian Week!

22 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Here’s Maglor for @feanorianweek . I liked this much better before I added the background, but that’s what I get for rushing it

112 notes

·

View notes

Photo

✨Tiny pastel Fëanorians collection✨ for @feanorianweek

💙Day 2- Maglor💙

86 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fire

@hello-from-valinor, you wanted a poem? You got one!

Crap, I just realized how lengthy it is. And it also started turning into prose halfway through. Sorry about that. Also @feanorianweek I know this is super late for Maglor day so I leave it to your discretion whether to reblog it or not. Thanks, guys!

Fire.

There is nothing else now.

There are no mountains.

There are no villages.

There is no sky.

There is nothing but the horse, the rider.

The horse gallops, nostrils flared,

Coughing and sweating through the smoke.

The rider leans low in the saddle, reins clutched in his hand,

Armor clanging as they flee.

There is nothing but the pounding animal, the panting elf,

And the swirling orange madness of dragon’s breath.

The worm’s maw is somewhere behind him.

A white-hot throat,

With blackened teeth the length of scythes

And scales of polished gold.

He knows this. He saw it.

He charged the beast,

Encircled it with warriors.

The worm gave no hint of fear.

It narrowed its eyes and stretched open its jaw

And it bathed them all in fire.

How many survived, he doesn’t know.

All he knows is the hell that surrounds him,

The desperate animal and the petrified rider,

On an earth that seems to be melting.

If he escapes the fire, he can regroup.

He can flee to his brother, his lord.

But his realm,

That place he had sworn to protect,

It is gone.

His people are dead.

His lands are burning.

He has failed them.

21 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Day 4: Caranthir, for @feanorianweek <3

I think most of Fëanor’s sons liked to have some animal company in their childhood. at least sometimes

72 notes

·

View notes

Link

A quintet of drabbles in the key of Maedhros.

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Feanorian Week Nerdanel Headcanons

@feanorianweek Day 2> Makalaure/Kanafinwë/Kano/Maglor

Maitimo loved children. When they had gone to meet Nolofinwë’s son Maitimo had taken one look at the baby and had completely fallen for him. He asked regularly for his uncle to let him babysit the elfling despite being barely past his majority himself. They bonded so much that little Finno’s first word was “Nelyo”, much to the delight of his cousin and the dismay of his father.

So, it was only natural that when Nerdanel informed him he was going to be a big brother his joy was greater even than his father’s. Before the end of the week all of Aman had heard the news from the young prince himself.

She felt tired for most of the pregnancy and more than once she and Fëanor worried about the lack of movement from the baby.

One day she was awoken from her slumber on one of the settees of the hearth-room by a hard kick on her bladder, only to find a pair of startled dark grey eyes looking up at her from her belly. The last note of Finno’s favorite lullaby still hung on her son’s lips.

After that, every time they worried about the baby’s stillness they would ask Maitimo to sing or play the flute for his sibling and each time the baby would get more and more active at the music stimuli.

Fëanor actually managed to speak whole sentences during the birth of their second child, even if they were the same three encouragements over and over again. Nerdanel began labour at the mingling of the lights, but it wasn’t until Laurelin was in alone in its light that the baby was born, crying and whelping loud and clear for everyone to hear him.

Nerdanel held her second son in her arms, Fëanaro stood above them. The child looked at his father and reached up to him. As those tiny hands grasped fervently at the golden-lit air Nerdanel had a vision of idle fingers playing the harp and making music worthy of the Ainur. And so Makalaure she would call him.

47 notes

·

View notes