#epiclassic

Text

Twin Topils, or, The Little Ruler List that Could

To begin a long, gruelling series of posts, I find it fitting to provide some manner of context beforehand.

Tollan (Xikokotitlan) in general is a bit of a historical clusterfuck, its history plagued with hundreds of years of accumulated exaggeration and further hundreds of interpreted and reinterpreted, lost and word-of-mouth'd sources. So as with many things, the truth is that no history will be truly complete, not with the materials we have today, probably never.

But one can, with a little scrawling madly at 12am, a good pen and a blank page, get closer to something old and forgotten: who the hell ruled Tollan before its demise.

Our journey begins with a long account of the years as perceived in Kwawtitlan. So the text is called, uh, Annals of Kwawtitlan.

It presents us with appearances of various rulers of various places, walking through time at a pace of its Xiwpoalli years, occasionally calling back to older events, occasionally retelling poems and prose stanzas of things said to have happened.

Walking back and making note of names, we arrive at the following list for the rulers of Tollan:

It should be noted that this is indeed a wiki table, albeit with an odd offset of 52 years from the original. This is intentional, I'd gone and did the walk back sometime ago but never bothered to reflect it on the wiki page, simply noted it in a final parenthesis to its introductory line.

Whichever the case, making a list of just this one source would be... irresponsible at best. There are other sources, the most popular of which are Ixtlilxochitl's various lists, five texts he wrote over the course of his life. These are all differently-dated, but they serve us well in most cases:

Ixtlil lists entirely different names except for one, Wetsin, though his dates are rather more distant into the past, getting somewhat closer as he writes more and (presumably) gathers and moves around now-lost sources.

What's notable about his lists is that the first one, within the Historia de la Nación Chichimeca, ends with a certain Topiltsin that's preceded by an Istakkaltsin. As time goes on, he adds changes a few names: Tlakomiwa to Mitl, Istakkaltzin to Tekpankaltsin, Xiwsaltsin to Xiwtlaltsin, and adds an Ix- to the beginning of Tlilkuechawak. He also seems to have discovered a new ruler, Mekonetsin, who he initially thought to have been another name for Topiltzin. He was instead his son, whose mother was a certain Xochitl, who we suggest had participated in the civil war of their time and deposed Topiltsin, whereafter she ruled for an unspecified number of years, then their son after her passing. This table doesn't include her for some reason.

Notes and parallels abound, but for now we will turn to Chimalpain's rather short list of rulers: Wemak (993-1029) and Akxitl Topiltsin Ketsalkoatl (1029-1051). He merely lists, it appears, those closest to the people he wrote this about, in a certain Brief memory of the founding of the city of Colhuacan.

Chimalpain had made a few mistakes elsewhere, apparently shifting a few rulers to the period of the one who preceded them. Thus, tentatively, his list would need to be re-evaluated as pertaining to a few years later, at least 22.

Most other lists are rather close to the two first ones, but there is one with a curious divergence.

The Anónimo Mexicano lists the first five all the same (Chalchiwtlanetl, Ixtlilkwechawak, Wetsin, Totepew and Nakaxok, who here is mangled as Nakaskayotl), but it jumps straight to Mitl, entirely skipping Istakkaltsin and Mekonetl. After Mitl, the regular order seems to come back with Xiwtsalli, but then we learn she ruled for only four years, after which a regency council was installed.

We are not told for how long did such a situation exist, but we are informed that a certain Tekpankaltsin ruled after its dissolution, and that he was the very last monarch of the city.

There is little more that we can use for our reconstructions, but three more sources are pivotal in orienting us. Torquemada, in his Monarquía Indiana, presents to us the knowledge that Tekpankaltsin also bore the name "Topiltsin," while the Annals of Kwawtinchan (by another name, the Historia Tolteca-Chichimeca) inform us that the last ruler of Tollan was Wemak, he whose iron fist caused instability and who became subject of the second coup in the city's history, and that a certain Wewetsin lineage of Nonoalka-chichimekah had a quarter of the city after being one of a few primary chichimeka groups to move to the area. Finally, the Codex Xolotl provides note that Tollan had been completely abandoned by 1175, a date generally supported by archaeological findings at the city reported by Healan et al.

It would appear that some common sources were used here.

Firstly, the most primordial one.

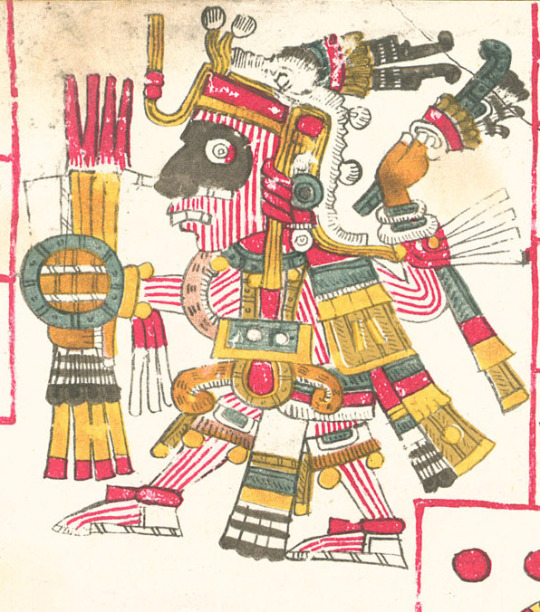

Both the AnaKwaw and Ixtlilxochitl's final list have 9 rulers, a few of which appear to be variant readings of certain glyphs: Mitl ("arrow") may be an abbreviated glyphic form of Tlakomiwa (meaning "possessor of wooden arrows"), which in turn is Mixkoatl's signature representation:

We could go on about the apparent snake around his right elbow resembling the convention for drawing masakoah, horned snakes, but this information is not entirely useful for us beyond "neat, might be whence the masatsin came from."

Also disclaimer bc ik this is actually from somewhere in the Puebla-Tlaxcala area: he hath the same traits in the Telleriano-Remensis. I just like this one a little more :)

Anyway, another name with a variant may be Xochitl, being merely "Xochitl" in Ixtlilxochitl (heh heh) and "Matlakxochitl" (10-flower, a calendarical name) in the AnaKwaw, where she directly succeeds Se Akatl.

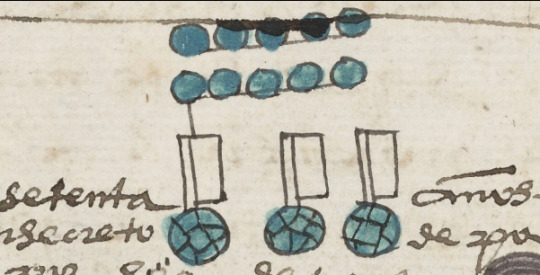

Akxitl, meanwhile, may be a conjunct case of mangling, abbreviation and variant readings: it may very well be reconstructed as Ak[atl]-xitl, but the latter part is seldom used in names Just Like That. Instead, that may be a slight mangling of xiwitl, a word whose glyphic form is a turquoise circle, but which can be quite easily confused with the turquoise dots that make a number count when alone. Thus, a single blue dot and a reed may very well be read as Akaxiwitl, but also as Ce Akatl.

(Note: i didn't come up with all of this — the Se Akatl : Aka[tl]-xiwitl theory was proposed by a fellow scholar who goes by Jan online. Thx @261jan)

It may not have been a single ancestral source, but at least two or perhaps three (one went to AnaKwaw author(s), one to Anón. and Ixtlil, while Chimal may have an additional one that Ixtlil also consulted later on) that were involved, co-temporally produced and recording events that were basically the same, but with slightly differing glyph usage and timing.

It's easy to deduce a closer connection between Ixtlilxochitl, Chimalpain and the Anónimo, although then we'd need to take a closer look at who consulted who here.

The only one who tells us who he read outright is Chimal. Most of his' are primarily Chalko and particularly Amakemekan and Tenanko (such as the [seemingly] Título Primordial written by Rodrigo de Rosas Xohecatzin, his father-in-law), but there are a few that come to mind as likely candidates: his two "small and veritable books" — which, by the sound of them and the apparent lack of focus on lineage or years, may have been historical-cartographical works resembling the Xolotl and Huamantla codexes —, and two glossed genealogies.

He had two more written sources, a Xiuhtlapohualamoxtli (an annal) with an apparent exclusive focus on Amakemekan, and the aforementioned Título dealing with the innards and local delimitations of the same place. Additionally, we have word of two oral testimonies he solicited, one on the provenance of a genealogy and the other on the lineage of a Chalka noble.

It is quite possible he first got the names from such genealogies, particularly those concerning Kolwakan, while the dates he may have confirmed with the Xiwtlapowalamoxtli. We know this because his dates for certain rulers in all his other lists prior to a certain point in time, notably those from Kolwakan, seem to occasionally backslide into what other sources suggest are instead the periods of their predecessor; Tollan, seemingly, also has this quirk within Chimal's writings.

The Xiwtlapowalamoxtli, then, is our likely culprit.

This work was congealed from various sources, and indeed may have utilized a source that Ixtlil later got his hands on, or which his sources in turn did.

The Anónimo and Ixtlil are rather analogous rather clearly; geographically, the former appears to have been produced in the general area of Tlaxcala, which overlapped and bordered in a few places with Akolwakan, the realm where Ixtlil lived and whence he harvested his sources.

Unifying all this info, at last, we may begin to reconstruct a list of who the hell did rule Tollan, although approximate.

The Six Kings of Legend

Chalchiwtlanetl, 511-562

Ixtlilkwechawak, 562-614

Wewetl, Lineage-maker; 614-666

Ilwitimal, Totepew ("our lord"); 666-718

Nakaxok, 718-770

Divided City, 770-826

Mixkoamasatl/Tlakomiwa, First Theocrat; 826-874

Theocracy, the Heavenly Monarchs

8. Se Akatl ("Akxitl") Ketsalkoatl, 874-880

9. Matlakxochitl, 880-ca. 927

10. Mekonetl, ca. 927-983

11. Xiwtlalli, 983-987

Instability, Lieges of Rubble

12. First Regent Council, 987-1000

13. Second Regent Council, 1000-1029

14. Wemak, Stone King; 1029-ca. 1070s?

15. Third Regent Council? ca. 1070s-ca. 1100s

16. The Last Prince, 1100s-ca. 1150?

17. Second Divided City? ca. 1150-1172

Of course, the first 7 periods are 52-years long or about. They are symbolic periods, and are mostly meant symbolically. Though evidence for a Tollan at all can be glimpsed as early as the Late Formative/Preclassic, it becomes larger and more relevant when the mid-500s roll up, which is right around our starting date here.

Within these symbolic periods, the Divided City is of particular note, as it most likely represents a period of both great change, instability and parallel power between its components, being more of a "confederation" than a proper "unified polity," though this was in a rather small area of course.

Wewetsin may have been a sort of unified, mythicized leader of the Nawa migrants pouring in from the west and into the Mezquital, where some would stay in, indeed, a quarter of the city, while others would walk on and take ideas with them from the nascent trading and cultural centre south, eventually contributing to a sort of "International Style" for Epiclassic Mesoamerica — they themselves would introduce a few things where they went, including most possibly the chacmool altars, as they appear quite earlier in Chalchihuites than anywhere else, albeit in a rather indecorous form.

Ilwitimal meanwhile may have begun the construction of Tula Grande, while the period of instability under Nakaxok and the Divided City may have unfluenced the shift from Tula Chico, while TG was mostly finished in its first phase by Mixkoamasatsin, the first lord of the "renewed" Tollan in its totality.

After his rule, it appears all rulers adopted the title of Tekpankaltsin, "who dwells in the palace," while specific provenances (such as Se Akatl's training and ordainment at the temple of Ketsalkoatl, associated with the wind and everything inked white) may have also been used as the basis for titles, such as Se Akatl's alternate name, Istakkaltsin ("dweller of the white house").

Either within his period or upon the ascension of Mekonetl, Tollan's rulers began styling themselves as Topiltzin, "our honoured prince;" all these titles may have induced some confusion and mix-ups in authors with only fractional context, who perhaps read mentions of certain names in specific periods and, instead of noting them as different names for the same people, may have both separated and unified certain rulers as they believed truest — Mekonetl as the first and the Forgotten King as the last Princes, then these both and Wemak and Se Akatl as Palace-Dwellers.

Se Akatl Istakkaltsin, for his part, may have been overambitious in attempting to quickly deal with the difficulties caused by his father's movement of the city and just generally bad times; if his story is to be read in the flourish of songs and poetry, he may have turned to alcohol and other pleasures, neglecting the military and economic needs of a city in the middle of a region-wide sociopolitical transition.

Notable are the inclusions of both Matlakxochitl and Xiwtlalli in most sources, as Nawa sources post-Etetl expansion tend to omit such notable figures on the basis of their own systems, even within their own lineages — Atotostli and Ilankweitl are paramount examples of quite notable but often-erased queens.

Matlakxochitl for her part was quite the political manoeuvrer: while Se Akatl's position was crumbling by the minute, Xochitl involved herself in the plots to bring him down, managing to instead replace him and rule for an unknown amount of years, reducing unrest and paving the way for some short stability that seems to have earned Tollan its reputation as a centre of culture and prosperity towards its later years.

Xiwtlalli did step down for reasons that remain uncertain, and not much is known about her rule. Perhaps, if we choose to interpret her name in specific ways, she brought great wealth and prosperity to hr land as well, if for a short time.

In her place then sat a Regent Council, better organized than the one which preceded Wemak and with slightly more input from each unit of the city, probably named something-coatl after Mixkoamasatl, paralleling the founding of a new order of sorts.

Wemak, Xiwtlalli's son, had to wait a long time for his crown. Perhaps here he developed a propensity for throwing tantrums and being greedy, attempting to eat the world all for himself. This, it appears, made more than a few quite angry, and thus he was ousted. Many left the city for good, and in many places he's thus called the final king of the place.

And the Regency resumed.

The Last Prince, unnamed and basically unknown, knew he had it hard. He may have come from the same context as Se Akatl, or perhaps this too is merging from old sources. He too eventually fell to the city's problems, divided between those who had stayed since the beginning and those who found it relatively easy to leave their residence once more. So the city crumbled into a deep, factional state, and he simply left after realizing he had basically no power to do anything for it. He left, perhaps sea-wards, perhaps to the Royal Family's old allies in Kolwakan, and perhaps he vowed to return. In his wake, all who remained would leave as well, sooner or later.

Some say he went to Cholollan and got himself into politics there. Cholollan, however, rather outspokenly despised Tollan, for both rose immensely in power after Teotiwakan's demise. Trade was strictly forbidden between the two centres and their dependencies, so it passed through a market kingdom in Anawak Metstliapan, on the coast of the Valley of the Five Lakes. This was Cerro Portezuelo, a site a little to the south of Tetskoko, possibly the Otumba Chimalpain mentions as one of the three regional hegemons of Tollan's age.

And with that, we can wrap this up at last, and prepare for the shitfest to come when we touch on such figures as Maarten and Mautner, and understand the mytho-historical relevance of this place. All in good time, all in good time.

Sources:

José Rubén Romero Galván (1977): Las fuentes de las diferentes historias originales del Chimalpahin

Dan M. Healan, Robert H. Cobean, & Robert T. Bowsher (2021): Revised Chronology and Settlement History of Tula and the Tula Region

Keith Jordan (2016): From Tula Chico to Chichén Itzá: Implications of the Epiclassic Sculpture of Tula for the Nature and Timing of Tula-Chichén Contact

Hanns J. Prem (1999): Los reyes de Tollan y Colhuacan

Alonso Bejarano & Pedro de San Buenaventura (n.d) via Primo Feliciano Velázquez (1992): Anales de Cuauhtitlan

Domingo Francisco de San Antón Muñón Chimalpahin Quauhtlehuanitzin (ca. 1631) via Víctor M. Castillo F. (1991): Memorial breve acerca de la fundación de la ciudad de Culhuacan

Unknown (n.d) via Richley H. Crapo & Bonnie Glass-Coffin (2005): Anónimo Mexicano

— via Paul Kirchoff, Lina Odena Güemes & Luis Reyes García (1976): Historia Tolteca-Chichimeca

— (ca. 1450s?): "Codex Xolotl"

Juan de Torquemada (1615): Monarquía Indiana, book I, chapter XIV

#the tula series (tm)#middle classic#epiclassic#middle postclassic#effortpost outtakes#it'd be a whole effortpost if it wasn't just 5 pages but whatever#ಠ_ಠ#< tfw using ixtlil *and* torquemada

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Test Bank for Ancient Mexico and Central America Archaeology and Culture History Third Edition by Susan Toby Evans

Download

Contents

Part 1: Mesoamerica, Middle America, and its Peoples

Chapter 1: Ancient Mesoamerica, The Civilization and Its Antecedents

Chapter 2: Ecology and Culture: Mesoamerican Beginnings

Chapter 3: Archaic Foragers, Collectors, and Farmers (8000–2000 BC)

Chapter 4: The Initial Formative (c. 2000–1200 BC)

Part 2: Complex Societies of the Formative

Chapter 5: The Olmecs: Early Formative (c. 1200–900/800 BC)

Chapter 6: The Olmecs: Middle Formative (c. 900–600 BC)

Chapter 7: Middle to Late Formative Cultures (c. 600/500–300 BC)

Chapter 8: The Emergence of States in the Late Formative (300 BC – AD 1)

Chapter 9: The Terminal Formative (AD 1–300)

Part 3: Cultures of the Early Classic

Chapter 10: Teotihuacan and Its International Influence (AD 250/300–600)

Chapter 11: The Maya in the Early Classic (AD 250–600)

Part 4: Late Classic, Classic Collapse, and Epiclassic

Chapter 12: The Lowland Maya: Apogee and Collapse (AD 600–900)

Chapter 13: The Late Classic and Epiclassic in the West (AD 600–1000/1100)

Chapter 14: Maya Collapse and Survival (AD 800–1200)

Chapter 15: The Rise of Tula and Other Epiclassic Transformations (AD 900–1200)

Part 5: The Postclassic and the Rise of the Aztecs

Chapter 16: The Middle Postclassic (1200s–1430)

Chapter 17: The Aztecs: An Empire Is Born (1430–1455)

Chapter 18: The Aztec Empire Develops (1455–1486)

Chapter 19: The Aztec Empire at Its Height (1486–1519)

Chapter 20: The Conquest of Mexico and Its Aftermath

Reference Maps

Pronunciation Guide

Further Reading and Bibliography

Sources of Illustrations

Index

Read the full article

0 notes

Text

Test Bank for Ancient Mexico and Central America Archaeology and Culture History Third Edition by Susan Toby Evans

Contents

Part 1: Mesoamerica, Middle America, and its Peoples

Chapter 1: Ancient Mesoamerica, The Civilization and Its Antecedents

Chapter 2: Ecology and Culture: Mesoamerican Beginnings

Chapter 3: Archaic Foragers, Collectors, and Farmers (8000–2000 BC)

Chapter 4: The Initial Formative (c. 2000–1200 BC)

Part 2: Complex Societies of the Formative

Chapter 5: The Olmecs: Early Formative (c. 1200–900/800 BC)

Chapter 6: The Olmecs: Middle Formative (c. 900–600 BC)

Chapter 7: Middle to Late Formative Cultures (c. 600/500–300 BC)

Chapter 8: The Emergence of States in the Late Formative (300 BC – AD 1)

Chapter 9: The Terminal Formative (AD 1–300)

Part 3: Cultures of the Early Classic

Chapter 10: Teotihuacan and Its International Influence (AD 250/300–600)

Chapter 11: The Maya in the Early Classic (AD 250–600)

Part 4: Late Classic, Classic Collapse, and Epiclassic

Chapter 12: The Lowland Maya: Apogee and Collapse (AD 600–900)

Chapter 13: The Late Classic and Epiclassic in the West (AD 600–1000/1100)

Chapter 14: Maya Collapse and Survival (AD 800–1200)

Chapter 15: The Rise of Tula and Other Epiclassic Transformations (AD 900–1200)

Part 5: The Postclassic and the Rise of the Aztecs

Chapter 16: The Middle Postclassic (1200s–1430)

Chapter 17: The Aztecs: An Empire Is Born (1430–1455)

Chapter 18: The Aztec Empire Develops (1455–1486)

Chapter 19: The Aztec Empire at Its Height (1486–1519)

Chapter 20: The Conquest of Mexico and Its Aftermath

Reference Maps

Pronunciation Guide

Further Reading and Bibliography

Sources of Illustrations

Index

Read the full article

0 notes

Text

Xochicalco: New Wave Mayan City That Was a Prime Target for Destruction

Following the Mesoamerican Classic Period of relative stability in the Mayan kingdom, the region fell into turmoil as battles for power raged and the established order was overturned. Out of this, cities emerged, some on the foundations of established citadels. Perhaps the strongest of these cities was Xochicalco, but its glory was short lived, as its strength became its downfall. The ruined city does give fascinating insights into the importance of shared religious beliefs in unifying cultures.

Read more...

#Mesoamerican#Places#Mayan#Americas#Epiclassic#citadel#city#ballcourt#plaza#pyramid#international#tiered#terraces#steps#temple#observatory#stele#feathered#serpent

34 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Ixtepete, Jalisco (c. 1940) prior to excavation. Ixtepete is an Epiclassic (400 - 900 A.D.) period site located near Zapopan in the Atemajac Valley (where Guadalajara is)

https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/El_Ixt%C3%A9pete

https://mediateca.inah.gob.mx/repositorio/repositorio_mediateca

37 notes

·

View notes

Quote

The propositions of M[arx] are based on the assumption that the comp[osition] of any large agg[regate] of commodities (wages, profits, const[ant] cap[ital]) consists of a random selection, so that the ratio between their aggr[egate] (rate of s[urplus] v[alue], rate of p[rofits]) is approx[imately] the same whether measured at 'values' or at the p[rices] of prod[uction] corresp[onding] to any rate of s[urplus] v[alue].

This is obviously true, and one would leave it at that, if it were not for the tiresome objector, who relies on hypothetical deviations: suppose, he says, that the capitalists changed the comp[osition] of their consumption (of the same aggr[egate] price) to commod[itie]s of a higher org[anic] comp[osition], the rate of s[urplus] v[alue] would decrease if calc[ulated] at 'values', while it would remain unchanged at p[rices] of p[roduction], which is correct? - and many similar puzzles can be invented.

(Better: the cap[italist]s switched part of their consumption from comm[oditie]s of lower to higher org[anic] comp[osition], while the workers switched to the same extent theirs from higher to lower, the aggr[egate] price of each remaining unchanged...)

It is clear that M[arx]'s pro[position]s are not intended to deal with such deviations. They are based on the assumption (justified in general) that the aggregates are of some average composition. This is in general justified in fact, and since it is not intended to be applied to detailed minute differences it is all right.

This should be good enough till the tiresome objector arises. If then one must define which is the average to which the comp[osite] should conform for the result to be exact and not only approximate, it is the St[andard] Comm[odity]...

But what does this average 'approximate' to? i.e. what would it have to be composed of (what weights sh[oul]d the average have) to be exactly the St[andard] Com[modity]?

i.e. Marx assumes that wages and profits consist approximately of quantities of [the] st[andard] com[modity].

Piero Sraffa

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

“El Creador” Morelos, Xochicalco during the Epiclassic period (AD 700 - 900). Taken at the Museo Nacional de Antropología, Mexico City

44 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Fragment 4884: Personage with Tezcacuitlapilli Anonymous Artist c. 600-900 AD In the area known as Mesoamerica, a concept coined by Paul Kirchhoff in 1943, there is a wide swath along the Gulf Coast of México, where Olmec art had its splendor, as did Totonac and Huastec culture. This fragment with Tezcacuitlapilli comes from Las Higueras, archeological site of the Mesoamerican Epiclassic period. It was found attached to “Building 1” and excavated only in 1968 by Ramon Arellanos Melgarejo, pioneer of Veracruz archeology and researcher of Anthropology at the Institute at Universidad Veracruzana. In this fragment of mural painting, it is possible to see a seated person with red body paint, blue feathers, accessories, and jewels in blue tones resembling turquoise, and with clothing typical of priests and warriors associated with Quetzalcoatl, the main god of Mesoamerica. During the archaeological excavations in Las Higueras in the 1970s, about 200 fragments of pre-Hispanic mural painting were detached, similar to the 18th and 19th century conservation and restoration efforts for Pompeian frescoes, though hopefully with less interference from treasure-hunters. Since 2001, visitors can walk around the archaeological and museographic reconstruction carried out by the archaeologist and museographer Rubén Morante López and a wide team of diverse specialists, which you can see in the Anthropology Museum of Xalapa, Veracruz, Mexico.

12 notes

·

View notes

Note

What do you mean when you refer to the surplus approach

basically just the broad tradition that concerns itself with a study of surplus producing/distributing modes. relevant thinkers would be the majority of the pre/classicals (especially the physiocrats but also smith, ricardo, etc), their critics (marx in particular but people like the ricardian socialists generally fall into this camp too), and the group that i term the epiclassicals (like sraffa, and maybe marx depending on your reading of him).

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Cacaxtla, Tlaxcala

During the epiclassic period, Cacaxtla was an important site for many reasons. Most notably its position in the trade routes that existed from Central America to the northern regions of Mexico.

The murals on the walls are famous for being so conserved. Their colors are vibrant and these pictures definitely do no give them justice. An interesting feature is that they are drenched with Mayan influence. In fact, it is theorized that the person who did the murals was either someone who was inspired by Mayan or an actual Mayan person.

The long mural represents a fight between the Jaguar and the Eagle; night and day. Several elements of the murals depict a form of Mayan bloodletting that was accomplished with a long tie.

The artwork of the site also consistently have images of Venus. It is theorized that the site was devoted primarily to the planet. An interesting feature is the section that function as cages. Archeologists found remnants of many birds that are no native to the valley of Puebla-Tlaxcala, like macaws.

And of course, the view from the top is amazing.

261 notes

·

View notes

Text

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Tula-Chichen-Tollan Connection

This was a paper I wrote for a class that essentially summarizes the book Twin Tollans: Chichén Itzá, Tula, and the epiclassic to early postclassic Mesoamerican world edited by Jeff Karl Kowalski and Cynthia Kristan-Graham. I thought I would share the paper with you all. I hope you enjoy it.

--------------------------------

For over century academics have squabbled over the supposed connection between the pre-Columbian Central Mexican city of Tula and the northern Yucatan city of Chichen Itza. Tula, situated in the Mexican state of Hidalgo north of present-day Mexico City, was once the center for a culture that we attribute to the Toltec, a semi-mythical and historical culture that once influenced Central Mexico. Chichen Itza is located on the limestone shelf of the Yucatan peninsula, a little over 1100 kilometers away as the crow flies from Tula, and was once the capital of a large Maya polity engaged in extensive coastal trade. Despite the distance between the two centers, academics have created an entwined mixture built upon archaeological and historical interpretations, not data, to try to link these two cities together. As a result, the Tula-Chichen-Tollan connection has created its own sort of mythos that makes understanding this connection difficult to research.

Researchers have cut down entire forests and drained seas of ink for over a century as they debated back in forth in the pages of scholarly journals and university press books over whether a connection exists between Tula and Chichen Itza, what constitutes such a connection, and how that connection formed in the past. After this century plus long debate, academics are no closer to resolving this question than when they started. How and why such a connection between Tula and Chichen Itza first began is something that many scholars have seemed to forget or ignored in their pursuit of the Tula-Chichen-Tollan connection. This paper explores the historiography of the Tula-Chichen-Tollan connection by recounting how the connection began, what sorts of evidence scholars have tried to draw upon, issues in resolving the question pertaining to a connection, and finally concluding with my own thoughts on the connection and whether it exists between Tula and Chichen Itza.

Definitions

To understand the Tula-Chichen-Tollan connection debate, we must define a number of terms in order to understand the origin and debate regarding the connection. This is necessary due to scholars over the past century using some of the same terms to mean multiple things, which only add to the confusion and general noise regarding the research of this connection. Some scholars use these terms as lines of evidence to support or refute the Tula-Chichen-Tollan connection, but these will be discussed in more detail later.

The first important term to define is tollan, a Nahuatl word that means “place of reeds,” “place of bulrushes,” or “place of cattails” (Kowalski and Kristan-Graham 2007: 22). Nahuatl speakers use this word to denote a densely populated settlement, what we would think of as an urban or low density urban city (Isendahl and Smith 2013). The word tollan denotes a city because the number of people in a city is as plentiful as the number of reeds, bulrushes, or cattails found near bodies of water. The Aztec glyph for tollan reflects this connotation by depicting reeds and cattails near a pool of water. Of importance to the Tula-Chichen-Tollan connection is that Tollan is the name of capital city of the Toltecs mentioned in ethnohistoric accounts recorded in the decades following the conquest of Mexico. This is a point that I will revisit later.

Tollan is often paired with the city’s name to reinforce that connotation with reeds and large numbers of people, as with the case of Tollan Tenochtitlan, one of three capitals of the Aztec Triple Alliance, and Tullam Chollan, also known by its modern name Cholula (Kowalski and Kristan-Graham 2007: 22-23). Both Tenochtitlan and Cholula were the two most densely populated urban centers at the time of Spanish contact in 1519. Tollan was also used in Mesoamerica as an honorific title for some centers. If a center is paired with the word tollan it is often because that place is a focus of political power, has important ancestral beginnings for a culture, and where the most prestigious of the nobility lived (Kowalski and Kristan-Graham 2007: 22). For example, Cholula was not only a densely urban space, but it was also a point of pilgrimage for Mixtec nobility who would travel to the city to have their septum pierced as part of a rite to ascend the throne (Kowalski and Kristan-Graham 2007: 22-23).

However, tollan does not need to be used as separate word and could simply be used as a prefix, either –tul or –tol, to add to other place names. For example, Tulancingo was the name for three separate centers in Hidalgo, Veracruz, and Oaxaca respectively (Kowalski and Kristan-Graham 2007: 22). Despite tollan being a designation for an urban center and the use of prefixes to denote urban centers, at the time of contact in 1519 there were no settlements, occupied or abandoned, that were simply named Tollan. The closest example we have is the site of Tula (Kowalski and Kristan-Graham 2007: 24).

Archaeologists and historians gave the name Tula to the archaeological site located next to the modern town of Tula in the Mexican state of Hidalgo. When Fray Bernardino de Sahagún began writing his Historia General in the mid-16th century, he recorded myths about a Tollan once occupied by the Toltec, the supposed civilized half of Mexica ancestry. The Mexica, one of several ethnic groups that form what we call the Aztecs, were the founders of Tenochtitlan who were once chichimecas (“dog people”) that had roamed north-central Mexico before arriving to the Basin of Mexico sometime during the Late Postclassic. To solidify their claims to power, the Mexica married into families that had Toltec ancestry, the most noble and prestigious of ancestry to be descended from. Other than recording ethnohistoric accounts from the Aztec people, Sahagún also journeyed to the town of Tula in Hidalgo. During this visit, Sahagún made clear distinctions between the prehistoric ruins that we now call Tula and the contemporary town of Tula that he visited. Sahagún recorded the prehistoric ruins of Tula as tolla (or tollan) while the contemporary town of Tula next to the ruins was recorded as tulla (or tullan). Sahagún even differentiated between the peoples, with the prehistoric peoples of tolla referred to as toltecas and the contemporary people of tulla as tultecas (Kowalski and Kristan-Graham 2007: 25). Despite these clear linguistic differences, the ruins near Tula were associated with the name Tula rather than Tolla. This slight difference in names contributed to the academic debate of where the Tollan of ethnohistoric accounts was located, a point that I will return to later in this paper.

As mentioned previously, Tollan was the location of the Toltec people recorded in ethnohistoric accounts. By the 20th century, however, the term Toltec could refer to one of a number of differing things including: a descendant of Teotihuacan, the ancestor of the Aztecs, the art style found at the archaeological site of Tula, a follower of Topiltzin Quetzalcoatl, an honorific title for an ancestor or a skilled artisan, the name of the Central Mexican warriors thought to have conquered Chichen Itza, the name of the art style that these alleged invaders introduced to the Maya of Yucatan, the name of a horizon period between the abandonment of Teotihuacan and the rise of the Aztec Triple Alliance, and the supposed ancestors of the Quiche and other highland Maya peoples (Kowalski and Kristan-Graham 2007: 24). As we can see, terms and their definitions matter, especially considering that not all of these things necessarily relate to one another. For the purposes of this paper, Toltec will refer primarily to the people who once occupied the archaeological site of Tula and, to a less extent, the semi-mythical and historic ancestors of the Aztecs. The use of the term Toltec to refer to both of these groups is not because we assuming the semi-mythical ancestors of the Aztecs are the same people who once occupied Tula. Instead, the use of the term for both groups reflects both archaeological and ethnohistoric naming conventions.

So far, the terms focus on Central Mexico and not the Maya. This is the result of the Tula-Chichen-Tollan connection assuming that a Central Mexican influence spread to Chichen Itza without considering other possibilities. For example, perhaps it was Chichen Itza that influenced Tula or perhaps there is something larger happening during this time period involving the participation of both Tula and Chichen Itza. This one-sidedness is a reflection of the bias and confidence scholars have in being able to characterize what is or is not Maya. For those things that are not Maya, scholars could argue those things are Toltec or Central Mexican. Important to this discuss are two terms from the Maya region: Itza and Puuc.

Itza is name of a Maya ethnic group whose ancestral home is located in the Petén Itza region of Guatemala. Sometime at the end of the Terminal Classic period, the Itza are believed to have migrated north towards Yucatan where they helped to found the city of Chichen Itza (Kowalski and Kristan-Graham 2007: 35). One of the ruling families of Mayapan, a later Maya city seen to be the successor of Chichen Itza, called Cocom are believed to have originated from Chichen Itza. After the abandonment of Mayapan, remnants of the Itza ethnic group returned south to the Petén Itza region where they established Nojpeten, the last Maya kingdom to fall to the Spanish in 1697 (Jones 1998).

Puuc is a term that refers to a region of Yucatan and an artistic style employed at sites within that region. The Puuc region is located in the Puuc hills south of the modern city of Merida. Within the Puuc hills are a number of large centers like Uxmal, Sayil, and Kabah. One of the ruling families of Mayapan called the Xiu are believed to have originated from Uxmal (Kowalski 2007). Together with the Cocom family, they ruled Mayapan for several centuries before the Xiu slaughtered most of the Cocom family (Jones 1998). The Xiu ancestors would have been living at Uxmal at the time of Chichen Itza’s founding.

The Beginnings

The beginning of the Tula-Chichen-Tollan connection largely began in the 19th century, but had its roots in the early colonial period shortly after the conquest of Mexico. The first person to make an explicit connection between Tula and Chichen Itza was by Désiré Charnay, a French explorer and archaeologist at the end of the 19th century and into the early 20th century. While Charnay was not the first to note similarities between some of the sculptures documented and recorded at both Tula and Chichen Itza, Charnay’s contribution lay in his more rigorous work with excavating at Tula, describing in detail the sculptures and artifacts from the site, and drawing more explicit parallels with artifacts recovered from Chichen Itza (Gillespie 2007: 93). Charnay’s objective for comparing these two sites together was not because he believed they shared a special, exclusive relationship in the past. Instead, like other 19th century anthropologists, Charnay was preoccupied with notions of race or “stocks” of people (Gillespie 2007: 90-91). Charnay viewed the Toltec of Central Mexico as a “civilized people” that were the originators of indigenous American civilization. As they spread their influence throughout Mesoamerica, the Toltec left traces of their civilizing efforts on a number of pre-Columbian cities. Tula and Chichen Itza just so happened to be the two cities that Charnay selected out of several to illustrate and support his argument.

Charnay’s work at Tula and then his travels to Chichen Itza set the stage for the Tula-Chichen-Tollan debate. Because Charnay went first to Central Mexico and then to the Yucatan seeing artifacts and architecture at Tula before Chichen Itza, Charnay created this perception that influence was spreading out from Central Mexico to the Maya. Ethnohistoric accounts of a Toltec king sailing east, a point of discussion revisited in this paper, reinforced this perception. I cannot help but speculate that if Charnay had traveled to Chichen Itza first, instead of Tula, would Charnay be more awestruck by Chichen Itza’s monumentality and beautifully carved stone buildings than Tula’s unimpressive cobble stone work? Would Charnay have argued instead that the Maya were the ones who traveled in the past spreading their influence to Central Mexico? How would that have changed the Tula-Chichen-Tollan debate? We may never be able to answer these questions, yet the chain of events started by Charnay left a long lasting and powerful ripple in Mesoamerican archaeology that we still feel today.

Following Charnay’s initial comparisons between these two pre-Columbian cities, other researchers began turning towards texts to support or refute this connection. In the decades following the conquest of Mexico, Spanish colonials began recording indigenous oral histories or adding text to indigenous codices using the Latin alphabet as a means to make sense of the newly conquered area, find avenues to convert people to Christianity, and to legitimize indigenous political and property claims (Smith 2007: 586; Matthew and Oudijk 2007). Many of these oral histories fall into the realm of semi-mythical history in that they most likely recount recent events accurately, but older events may fall into the realm of myth (Smith 2007: 590-593). From some of these ethnohistoric accounts from Central Mexico we get tales of Topiltzin Quetzalcoatl, the supposed ruler of Tollan and Quiche ethnohistoric accounts from southern Mexico and Guatemala recount tales of migrations into the region. However, there are issues for scholars attempting to draw from these accounts to support the Tula-Chichen-Tollan connection.

When Spanish friars first began recording these oral histories, the friars repeatedly encountered a figure named Quetzalcoatl. Since their mission was to spread Christianity to this new region, the friars began focusing their attention on Quetzalcoatl. Aztec depictions of Quetzalcoatl the deity were often in human form giving the Spanish friars the false assumption that Quetzalcoatl was a physical person rather than a deity or icon. If the friars could understand who Quetzalcoatl was, the Spanish friars could somehow use this person to help convert the indigenous people to Christianity. However, because the friars were working under the assumption that Quetzalcoatl was a man and not a deity or an icon, the friars began to conflate all the names that used Quetzalcoatl into an amalgam of a single person. The result is a mess of conflicting accounts about who Quetzalcoatl was and what deeds they accomplished (Gillespie 2007: 89).

Quetzalcoatl is not merely the Nahuatl word to denote the feathered serpent deity of Central Mexico. The Aztec used Quetzalcoatl for the name or titles of people, real or mythical, in their oral historical accounts such as Ce Acatl Quetzalcoatl, Topiltzin Quetzalcoatl, and Nacxitl Quetzalcoatl. As with the variety of names and titles, so too, was there a variety of myths associated with the name Quetzalcoatl. For example, Quetzalcoatl is associated with being the last king of the Tollan dynasty, but other accounts place him to be the founder of the Tollan dynasty. Accounts differ on Quetzalcoatl’s demise, as well. Some say he traveled to the seacoast, to Tlapallan, a mythical place on the Gulf coast, or he simply traveled east. When Quetzalcoatl arrived to his destination he either sailed away, sacrificed himself to become the Morningstar, or he simply died (Gillespie 2007: 89). The conflicting details associated with Quetzalcoatl that the Spanish recorded were a result of when these accounts were written at different periods in the 16th century (Gillespie 2007: 107).

It is from these accounts that early academics began to wonder whether there was truth to Charnay’s suggestion that Tula (Tollan) and Chichen Itza relate to one another somehow. However, scholars attempting to draw from ethnohistoric accounts faced a conundrum. Western historical tradition in the 19th and early 20th century tended to treat documents as infallible and superior to archaeological information (Gillespie 2007: 106). As discussed, early colonial documents were inconsistent in the accounts and deeds of Quetzalcoatl, a person that may be more mythic than historic. Because of these conflicting accounts and the desire to draw upon historic documents, 19th century scholars lifted passages free from their contextual information to get at the “truth.” Scholars primarily drew upon later 16th century accounts influenced more by Spanish colonialism than early 16th century account in their search for historical information (Gillespie 2007: 107). The result was a “reconstructed” and “historic” account in which Quetzalcoatl was a human Toltec king of the city of Tollan located somewhere in Central Mexico. At some point during his reign, Quetzalcoatl fled Tollan for the Gulf Coast where he sailed east, presumably to Yucatan, bringing with him Toltec culture and civilization.

If these “historic events” could be gleaned or reconstructed from Central Mexican sources, academics were left asking if there was an equivalent in Maya ethnohistoric accounts. To their delight, Quiche ethnohistoric accounts do talk about their ancestors coming from Central Mexico, but these accounts, like the Chilam Balam, were written one to three centuries after the conquest of Mexico (Smith 2007: 587). As Michael Smith points out, migration is a common trope in indigenous mythic history and ethnic identity (Smith 2007: 592). It is not unusual to find other tales in other cultures of “stranger kings” who come to a region to rule a far off kingdom whether or not it was actually true. There is no reason for us to think that indigenous myths of migration are true without other lines of evidence (Beekman and Christensen 2003, 2011; Smith 2007: 593; Stone 2003).

Nonetheless, the Maya of Chichen Itza do have a Feathered Serpent deity called K’uk’ulkan. Part of the Tula-Chichen-Tollan connection is that the Toltecs brought with them a Feathered Serpent cult to Chichen Itza. This is based, in part, on the predominate Feathered Serpent imagery found in Central Mexico. However, the Feathered Serpent cult poses an issue in that it is largely associated with elite ideology. The method in which the Feathered Serpent cult expresses itself in material culture varies based on local religious, economic, and political conditions (Gillespie 2007: 102). It would be difficult to argue that the Toltec brought the Feathered Serpent cult to Yucatan unless without considering other methods of transmission. The argument concerning the transmission of the Feathered Serpent dieity becomes more complicated when you consider that friars Diego de Landa and Bartolome de Las Casas recorded in the 16th century that K’uk’ulkan originated in Yucatan and spread to the west becoming a god named “Cezalcouati” (Gillespie 2007: 90). Perhaps scholars would have latched on to this piece of knowledge had Charnay visited Chichen Itza first.

There are some interesting linguistic associations between the Feathered Serpent and the Maya that should be discussed. In the 16th century the Castillo, a radial stepped platform pyramid, located on the North Terrace at Chichen Itza was named K’uk’ulkan and was associated with a “historic” person and a deity (Gillespie 2007: 90). While this may not be unusual in the context of Charnay’s idea of the Toltec bringing culture to the Maya, there are some interesting linguistic associations that suggest an older, deeper relationship with the Feathered Serpent. In Mayan, there are a series of homophones in that these words sound similar, but mean different things. These words are kan which means “snake” or the number four, k’an which means “cross”, k’aan which means “cordage”, and ka’an which means “sky”. The Castillo itself is adorned with entwined serpents on its balustrades. The entwined serpents allude to the idea of divine cordage, which has Pre-Classic and Classic roots, and can be associated with the Mesoamerican cosmological idea of a Coatepec or Serpent Mountain. There are four stairways on the Castillo and, from above, the pyramid would look like a cross. During the spring equinox, the rising sun creates a shadow along one of the balustrades giving an illusion that a serpent is descending from the heavens down the pyramid to the carved serpent head on the ground. Within an earlier construction of the Castillo, archaeologists found a red painted jaguar throne that may be a representation of the Maize God’s creation throne. The Castillo thus represents a K’an Witz (witz meaning “mountain”) the Maya cosmological creation mountain rendered in a local Itza style by combining and expressing these different and associations in the architecture (Kowalski and Kristan-Graham 2007: 62).

Using textual evidence presents two very difficult problems. As mentioned already, Spanish recorded indigenous oral histories had their own agenda and intention. Oftentimes indigenous people used ethnohistoric accounts to solidify political claims in the Spanish colonial government. The other issue in using textual evidence is that none of the texts originates from the Toltec or Maya during the period in which scholars believed Tula (Tollan) and Chichen Itza were connected (Gillespie 2007: 92). These accounts are by later indigenous people and their ability to recall deeper past events is questionable (Smith 2007). For example, the later Aztec people portray the Toltecs as fantastic and exceptional metalworkers. However, when one looks at the archaeological record of Tula, the supposed capital of the Toltecs, one can see that the site of lacks substantial amounts of metal artifacts. Yet when we look at the archaeological record at Chichen Itza, which scholars argue is as Toltec as Tula, there are many more metal artifacts recovered at the site (Gillespie 2007: 100). There is also an issue in that there are no contemporary depictions of anyone with the name or designation of Ce Acatl Topiltzin Quetzalcoatl at Tula. Though there is an Aztec carving of someone named “one reed” and associated with a feathered serpent at Cerro la Malinche in Central Mexico, this is weak evidence to establish that Quetzalcoatl the name was a real person. This discrepancy is not easily resolved when trying to argue for this strong connection between the two sites.

Another example that calls into question the usefulness of textual information is the fact that there are no Maya hieroglyphics at Chichen Itza, or any other northern Yucatan site, that recount an event in which a group of Central Mexican people arrived to Chichen Itza, by force or otherwise. There is a different instance of Central Mexicans reaching the Maya, but this instance occurred centuries prior in the Classic period between Teotihuacan and Tikal. Not only do multiple Maya sites take note of this entrada, but the Maya depict these invaders in Teotihuacan style accoutrements (Stuart 2000). Due to the lack of textual evidence recording a Toltec invasion to northern Yucatan, scholars have used artistic evidence from the art and iconography at Chichen Itza to compensate for this deficiency, despite the fact that Chichen Itza made use of hieroglyphs up until the late 9th century when the Toltec would have made their connection (Gillespie 2007: 98; Grube and Krochock 2007; Kowalski 2007). Nonetheless, some scholars still do not see this as an issue and instead try to turn to other textual evidence and the archaeological record to bolster their argument.

Continual Myth Making

Despite Charnay’s somewhat superficial comparison of artifacts and sculptures recovered from Tula and Chichen Itza and the problems associated of using a chimerical account of a possibly fictitious person named Quetzalcoatl that traveled to Yucatan bringing Toltec culture to the Maya, scholars continued to pursue the perceived connection between Tollan and Chichen Itza into the 20th century. In the 20th century, scholars shifted their focus from textual evidence toward physical evidence gathered from art studies and archaeology to answer two questions: where was Tollan and how a connection could be established using material culture between Tollan and Chichen Itza?

Today, archaeologists and art historians regard Tula as the place referenced in ethnohistoric accounts as Tollan. As previously discussed, there were many Tollans at the time of contact in 1519 including Tollan Tenochtitlan and Tullam Chollan. Further, the prefixes tol- and tul- often were used to denote an urban center, as was the case with the name Tulancingo. At the time of contact, the historic town of Tula was the only place in Central Mexico with a name closest to Tollan that did not use Tollan as a secondary name or use a prefix. However, the historic town of Tula is not the same as the current archaeological site of Tula located nearby. Despite Spanish friars like Sahagun noting a difference between the contemporary people living at Tula and the historic people that once occupied the ruins, early scholars, like Charnay, proposed that site of Tula was the Tollan of myth. The fact that reeds grew in abundance at the El Salitre Swamp near the archaeological site and town somewhat bolstered this early argument. However, reeds also grew in abundance near the Great Pyramid at Cholula and on the island shores of Tenochtitlan. However, the Otomi name for Tula, Mahmeni, means “congregation of people” mirroring the definition of the Nahuatl word Tollan (Kowalski and Kristan-Graham 2007: 23).

Nonetheless, early scholars were not convinced Tula could be the Tollan of myth. Teotihuacan was proposed to be the Tollan of myth that spread Toltec culture throughout Mesoamerica before the advent of radiocarbon dating could anchor local ceramic chronologies (Gillespie 2007: 94-95). It took decades before archaeologists established a chronological period between the abandonment of Teotihuacan and the rise of the Aztec Triple Alliance. Teotihuacan seemed like the leading contender with its massive size, Feathered Serpent pyramid, striking artwork, and obvious place of reverence by later Central Mexican peoples. Tula, on the other hand, was this small, minor center in a marginal environment with aesthetic shortcomings that did not match ethnohistoric accounts. George Kubler (Kubler 1984: 83 cited in Kowalksi and Kristan-Graham 2007: 53) marked in a publication, “the expression attained by the sculptors of Tula differs from that of their predecessors at Teotihuacan by their choice of deliberately harsh forms, which avoided grace and sought only aggressive asperities, gritty surfaces, and bellicose symbols”.

The critiques of Tula did not stop with comparisons to Teotihuacan. Scholars viewed the architecture of Chichen Itza to be more sophisticated and cosmopolitan than Tula. George Kubler (Kubler 1961 cited in Kowalski and Kristan-Graham 2007: 34) remarked that the architecture at Chichen Itza was reflective of a “creative hearth” while Tula looked like it was some kind of “frontier garrison. Jorge Acosta remarked that, “Tula has a majestic conception, but a mediocre realization” (Acosta 1956-57:76 cited in Kowalski and Kristan-Graham 2007: 53). Despite these critiques and the desire to establish Teotihuacan as the Tollan of myth, Tula eventually won the academic debate. Jimenez Moreno, conducting excavations at Tula, was able to demonstrate via ceramics recovered at the site that Tula postdated Teotihuacan and predated the Aztec Triple Alliance (Gillespie 2007: 97). This placement was bolstered by the chronology in the Anales de Cuauhtitlan, a Central Mexican document on the history of Central Mexico, in which the Tollan recounted in the document was referring to Tula, not Teotihuacan (Gillespie 2007: 97).

The context of shared attributes shared between the sites of Tula and Chichen Itza consist primarily of architectural and sculptural similarities found within the respective civic ceremonial centers of each site. The most common architectural features cited as evidence of a connection are the colonnaded halls, the Atlantean statues, the feathered serpent sculptures, and the Chacmool sculptures. However, Tula and Chichen Itza do not exclusively share these elements nor do these elements originate in the Terminal Classic/Epiclassic or Postclassic periods. Of these shared elements, I will focus on just the colonnaded hall for this paper.

At Tula, the primary ceremonial building of importance is Pyramid B or the Temple of Tlahuizcalpantecuhtli (“Dawn Lord”) which consists of a stepped platform with hundreds of stone columns to support a perishable roof. The equivalent structure at Chichen Itza is the Temple of the Warriors that also consists of a stepped platform with hundreds of stone columns to support a perishable roof (Kowalski and Kristan-Graham 2007: 60-61). Each colonnaded hall has images of warriors carved on its stone columns, though Tula does not have nearly as many carved columns as Chichen Itza’s Temple of the Warriors. Surely, this is convincing evidence of some sort of special connection between the two sites, but the differences between the two sites cannot be remedied.

First, the focus of the ceremonial centers at either site differs. The focus of Tula’s ceremonial center is on Pyramid B, but at Chichen Itza, the ceremonial center is on the Castillo. In fact, the Temple of the Warriors at Chichen Itza is located off to the side on the North Terrace and is not oriented in the same manner as Pyramid B. In addition, Tula, despite having rather large buildings for a Central Mexican Epiclassic site, lacks an equivalent to Chichen Itza’s Castillo. If the Toltec did, in fact, influence Chichen Itza from its very founding, why is the ceremonial center at Chichen Itza not focused on the Temple of the Warriors? Moreover, are colonnaded halls really that special and unique? As Kristan-Graham (2007) points out, the tradition of colonnaded halls and sunken patios predates both Tula and Chichen Itza at sites in the Bajío and north Mexico, such as La Quemada and Alta Vista in Zacatecas, during the Classic period. Why do scholars not look for sites that have a radial stepped pyramid as the focus of their ceremonial center, like the Castillo at Chichen Itza? Nielsen, Helmke, and Fenoglio (2018) proposed that the site of El Cerrito, in Queretaro, should be considered a third Tollan in the Tula-Chichen-Tollan connection. This is due, in part, to its pyramid that is reminiscent of the Castillo as well as a dearth of other related iconographic elements at the site. While El Cerrito does have a colonnaded hall of sorts, its hall differs in form to that of Pyramid B or the Temple of the Warriors.

If we continue to pick at the differences between the colonnaded halls, more of the Tula-Chichen-Tollan connection falls apart. For example, the construction of the columns between Tula and Chichen Itza also differ. At Tula, the columns are constructed with four basalt blocks held together without anything while at Chichen Itza, the columns are constructed with soft limestone cobles and held together with mortar and plaster (Kowalski and Kristan-Graham 2007: 57). The content of the columns also differ. Kowalski argues that the columns at the Temple of the Warriors could be seen as an outgrowth of the Classic Maya stela practice in that the individuals depicted are personalized and reflect Maya iconographic traditions in the upper and lower registers that surround the subject. The columns at the Temple of the Warriors depict different people on all four sides, not just one, which differ slightly from the Classic period stela practice (Kowalski 2007: 268-269). At Pyramid B, however, the majority of the columns were not sculpted, though they could have had their plaster painted (Kowalski 2007: 271). Of the sculpted columns recovered at Tula, the subjects are less individualized and more formalized and symmetrical much like the depictions of warriors at Teotihuacan (Kowalski 2007: 269). Even with a similar architectural form, the construction and content of the colonnaded halls between Tula and Chichen Itza differs leaving us asking what sort of connection there is between these two centers.

Concluding Thoughts

These shared attributes between Tula and Chichen Itza are woefully insufficient to represent a “site-unit” intrusion of migrants from another area settling in a new area (Gillespie 2007: 102). While scholars may not be able to explain why Tula and Chichen Itza may share some of these elements, it is unlikely to be the result of some kind of Toltec invasion or conquest of northern Yucatan during the Terminal Classic. Pasztory notes few instances in Mesoamerican where one group actually used the art style of another, different group (Kowalski and Kristan-Graham 2007: 56-57). That leaves us asking, what does style even mean? Atkins (1990: 155) defined style in the context of art history as the belief that artworks from a particular era share certain distinctive visual characteristics. These include not only size, material, color, and other formal elements, but also subject and content.” Priority to form over content, but for Tula and Chichen Itza it favors content over form. Despite superficial similarities, there is no unified art style between the two sites (Kowalski and Kristan-Graham 2007: 55).

Tula and Chichen Itza were most likely participating in the same sort of power grab that other Terminal Classic sites were engaged in after the fall of Teotihuacan, Tikal, and Calakmul. The “Toltec” warriors depicted at Chichen Itza could very well be a form of ancestral recall or “validation through history” (Kowalski and Kristan-Graham 2007: 57). The Itza of Chichen Itza may have depicted some of their warriors with a “Toltec Military Outfit” which is similar to the Teotihuacan military outfit with pillbox helmets, bird or butterfly pectorals, and the use of atlatls and arts (Kowalski and Kristan-Graham 2007: 30). Instead of Chichen Itza establishing a relationship to Tula to solidify their political power, elites at Chichen Itza may have been referencing the Teotihuacan entrada from the Classic period in both the artwork and architecture of the site. This would not be an unusual move considering the Aztecs made similar references to their supposed Toltec ancestors to legitimize their claims to the Basin of Mexico.

Does this mean that there was no movement of people to Chichen Itza? To answer that question I would say no, people most likely did travel to Chichen Itza. The city was, of course, an important trade city able to import obsidian from Central Mexico and gold from Central America. We know from stable isotope studies that people did travel around Mesoamerica as evident by the remains of people recovered at Teotihuacan that have origins in the present-day states of Veracruz and Oaxaca (Manzanilla 2015). Another example comes from the remains of an individual recovered at Lamanai, Belize that may be of West Mexican origin (White et al. 2009). People moved around in the past and that is without a doubt. However, how scholars have tried to form and bridge a connection between Tula and Chichen Itza is problematic and poorly executed. What makes matters worse is the lack of unpublished data and work to create a solid chronology for each site (Smith 2007). Until many of these issues are resolved, I am of the mind that there was no special link between Tula and Chichen Itza.

Bibliography

Acosta, Jorge R.

1956-1957 Interpretación de algunos data obtenidos en Tula relativos a la época Tolteca. Revista Mexicana de Estudios Antropológicos 14(2):75-110.

Beekman, Christopher S., and Alexander F. Christensen

2003 Controlling for doubt and uncertainty through multiple lines of evidence: A new look at the Mesoamerican Nahua migrations. Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory 10(2): 111-164.

2011 Power, agency, and identity: Migration and aftermath in the Mezquital area of north-central Mexico. In Rethinking Anthropological Perspectives on Migration, edited by Graciela S. Cabana and Jeffery J. Clark, pp. 147-174. University Press of Florida.

Gillespie, Susan D.

2007 Toltecs, Tula, and Chichen Itza: The Development of an Archaeological Myth. In Twin Tollans: Chichen Itza, Tula, and the Epiclassic to Early Postclassic Mesoamerican World edited by Jeff Karl Kowalski and Cynthia Kristan-Graham, pp. 85-128. Harvard University Press.

Grube, Nikolai and Ruth J. Krochock

2007 Reading Between the Lines: Hieroglyphic Texts from Chichen Itza and Its Neighbors. In Twin Tollans: Chichen Itza, Tula, and the Epiclassic to Early Postclassic Mesoamerican World edited by Jeff Karl Kowalski and Cynthia Kristan-Graham, pp. 205-250. Harvard University Press.

Isendahl, Christian, and Michael E. Smith

2011 Sustainable agrarian urbanism: the low-density cities of the Mayas and Aztecs. Cities 31: 132-143.

Jones, Grant

1998 The Conquest of the Last Maya Kingdom. Stanford University Press.

Kowalski, Jeff Karl

2007 What’s “Toltec” at Uxmal and Chichen Itza? Merging Maya and Mesoamerican Worldviews and World Systems in Classic to Early Postclassic Yucatan. In Twin Tollans: Chichen Itza, Tula, and the Epiclassic to Early Postclassic Mesoamerican World edited by Jeff Karl Kowalski and Cynthia Kristan-Graham, pp. 251-314. Harvard University Press.

Kowalski, Jeff Karl, and Cynthia Kristan-Grham

2007 Chichen Itza, Tula, and Tollan: Changing Perspectives on a Recurring Problem in Mesoamerican Archaeology and Art History. In Twin Tollans: Chichen Itza, Tula, and the Epiclassic to Early Postclassic Mesoamerican World edited by Jeff Karl Kowalski and Cynthia Kristan-Graham, pp. 13-84. Harvard University Press.

Kristan-Graham, Cynthia

2007 Structuring Identity at Tula: The Design and Symbolism of Colonnaded Halls and Sunken Plazas. In Twin Tollans: Chichen Itza, Tula, and the Epiclassic to Early Postclassic Mesoamerican World edited by Jeff Karl Kowalski and Cynthia Kristan-Graham, pp. 531-578. Harvard University Press.

Kubler, George

1961 Chichen Itza y Tula. Estudios de Cultura Maya 1: 47-80. México D.F.

1984 The Art and Architecture of Ancient America: The Mexican, Maya, and Andean Peoples (3rd ed.). The Pelican History of Art. Penguin Books, Harmondsworth, Middlesex, England.

Manzanilla, Linda R.

2015 Cooperation and tensions in multiethnic corporate societies using Teotihuacan, Central Mexico, as a case study. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 112(30): 9210-9215

Matthew, Laura E., and Michel R. Oudijk (editors)

2007 Indian Conquistadors: Indigenous allies in the conquest of Mesoamerica. University of Oklahoma Press.

Nielsen, Jesper, Christophe Helmke, and Fiorella Fenoglio

2018 A Dark Horse of the Early Postclassic: The Site of El Cerrito (Queretaro, Mexico) and its Relationship to Chichen Itza and Tula. Paper presented at the 83rd Annual Meeting of the Society for American Archaeology, April 13th, Washington D.C.

Smith, Michael E.

2007 Tula and Chichen Itza: Are We Asking the Right Questions? In Twin Tollans: Chichen Itza, Tula, and the Epiclassic to Early Postclassic Mesoamerican World edited by Jeff Karl Kowalski and Cynthia Kristan-Graham, pp. 579-618. Harvard University Press.

Stone, Tammy

2003 Social Identity and Ethnic Interaction in the Western Pueblos of the American Southwest. Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory 10(1): 31-67.

Stuart, David

2000 The arrival of Strangers. In Mesoamericas Classic Heritage: From Teotihuacan to the Aztecs edited by David Carrasco, Lindsay Jones, and Scott Sessions, pp 465-513. University Press of Colorado, Boulder.

White, Christine D., Fred J. Longstaffe, David M. Pendergast, and Jay Maxwell

2009 Cultural Embodiment and the Enigmatic Identity of the Lovers from Lamanai. In Bioarchaeology and Identity in the Americas edited by Kelly Knudson and Christopher Stojanowski, pp. 155-176. University Press of Florida.

#archaeology#arqueologia#tula#chichen itza#mesoamerica#maya#toltec#history#historia#quetzalcoatl#feathered serpent#uxmal#hidalgo#teotihuacan#aztec

120 notes

·

View notes

Text

Anthropomorphic Imagery in the Mesoamerican Highlands: Gods, Ancestors, and Human Beings

edited by Brigitte Faugère & Christopher Beekman

---

In Anthropomorphic Imagery in the Mesoamerican Highlands, Latin American, North American, and European researchers explore the meanings and functions of two- and three-dimensional human representations in the Precolumbian communities of the Mexican highlands. Reading these anthropomorphic representations from an ontological perspective, the contributors demonstrate the rich potential of anthropomorphic imagery to elucidate personhood, conceptions of the body, and the relationship of human beings to other entities, nature, and the cosmos.

Using case studies covering a broad span of highlands prehistory—Classic Teotihuacan divine iconography, ceramic figures in Late Formative West Mexico, Epiclassic Puebla-Tlaxcala costumed figurines, earth sculptures in Prehispanic Oaxaca, Early Postclassic Tula symbolic burials, Late Postclassic representations of Aztec Kings, and more—contributors examine both Mesoamerican representations of the body in changing social, political, and economic conditions and the multivalent emic meanings of these representations. They explore the technology of artifact production, the body’s place in social structures and rituals, the language of the body as expressed in postures and gestures, hybrid and transformative combinations of human and animal bodies, bodily representations of social categories, body modification, and the significance of portable and fixed representations.

Anthropomorphic Imagery in the Mesoamerican Highlands provides a wide range of insights into Mesoamerican concepts of personhood and identity, the constitution of the human body, and human relationships with gods and ancestors. It will be of great value to students and scholars of the archaeology and art history of Mexico.

---

Contributors: Claire Billard, Danièle Dehouve, Cynthia Kristan-Graham, Melissa Logan, Sylvie Peperstraete, Patricia Plunket, Mari Carmen Serra Puche, Juliette Testard, Andrew Turner, Gabriela Uruñuela, Marcus Winter

Brigitte Faugère is professor at the Université de Paris I Panthéon-Sorbonne. An archaeologist specializing in the north-central and western parts of Mexico, she is the director of an excavation project on the Preclassic Chupícuaro in the Lerma Valley and author of Entre Zacapu y Río Lerma: Culturas en una zona fronteriza, Las representaciones rupestres del centro-norte de Michoacán, and Cueva de los Portales: Un sitio arcaico de Michoacán, México.

Christopher Beekman is associate professor of anthropology at the University of Colorado Denver. His research focuses on sociopolitical organization in ancient western Mexico. He has directed excavation projects at Llano Grande and Navajas and surveys in the La Primavera region and the Magdalena Valley. He is a coauthor of the first volume of the Historia de Jalisco and has coedited several books, including Shaft Tombs and Figures in West Mexican Society.

---

Order now and use promo code FAUG19 to get 40% off! - http://campaign.r20.constantcontact.com/render?m=1102467236383&ca=08187121-2da9-4419-9a8c-efe9a378e881

University Press of Colorado page - https://upcolorado.com/university-press-of-colorado/item/3733-anthropomorphic-imagery-in-the-mesoamerican-highlands

#archaeology#arqueologia#mesoamerica#mexico#art#arte#history#historia#books#reading#west mexico#aztec#puebla#tlaxcala#Teotihuacan

29 notes

·

View notes

Photo

'Kneeling Warrior' Effigy Jar

Date: 850-950

Origin: Mexico, Pacific Coast (Suchiate River Valley)

Provenience unknown, possibly looted

Maya plumbate kneeling warrior vessel, Epiclassic period, on his left knee, holding a pointed club near his thigh. There is a rectangular incised and plumed (?) shield at the side, and the right hand is holding another pointed club and resting on his raised right knee. The vessel has a block-like head with tubular projecting eyes and rectangular mouth, and is wearing loin-cloth, shirt, and necklace incised and tied at the back. Areas of gold leaf remaining on his head.

Gardiner Museum

#archaeology#arqueologia#mexico#chiapas#maya#mesoamerica#art#arte#history#historia#rio suchiate#pacific

31 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hello! Do you know how society in the shaft tomb cultures of West Mexico (mostly talking about Nayarit, Jalisco and Colima) changed from the Classic to Postclassic periods? Were they still doing shaft tombs? What was their relation to the Tarascans and Chichimecs?

There is a complete break in the archaeological record from the Classic to Epiclassic period. People stopped digging shaft tombs, they stopped making hollow ceramic figures (in Classic period styles or anything similar), they stopped constructing guachimontones (Jalisco and Colima), they used completely different ceramic forms, types, and decorations, they used completely different tool technologies (prismatic blades were introduced), they even built new centers away from Classic period settlements. There is basically zero continuity between the two periods.

Beekman has argued that this was because Nahuatl speaking migrants from the Bajio invaded the West and displaced or disrupted Classic period peoples. Later waves of migrants would have brought in the Uacúsecha (one-half of the Tarascan lineage) and the Caxcanes (Huitzilopochtli worshipers who fought the Spanish in the Mixton War).

So there is no relationship between the shaft tomb peoples and the later Tarascan and Chichimec peoples as far as we can tell based on the archaeological record (including art and iconography). Now, DNA testing may say otherwise if we can find enough preserved remains to do some kind of testing on. That’s going to be difficult given that bone does not preserve well in that region.

I will say, though, that the Huichol people do appear to have some cultural characteristics that are eerily similar to things we see for the Teuchitlan culture (local shaft tomb group) in Jalisco. It’s almost as though the ancestors of the Huichol interacted with the Teuchitlan culture in the past and kept some of the traditions alive (or perhaps are the descendants of the Teuchitlan culture people). DNA testing would be insightful in this matter.

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/307795254_Causes_and_Consequences_of_Migration_in_Epiclassic_Northern_Mesoamerica_Toward_a_Unifying_Theory_of_Ancient_and_Contemporary_Migrations

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/289080854_Power_agency_and_identity_Migration_and_aftermath_in_the_Mezquital_area_of_north-central_Mexico

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/225150376_Recent_Research_in_Western_Mexican_Archaeology

33 notes

·

View notes

Photo

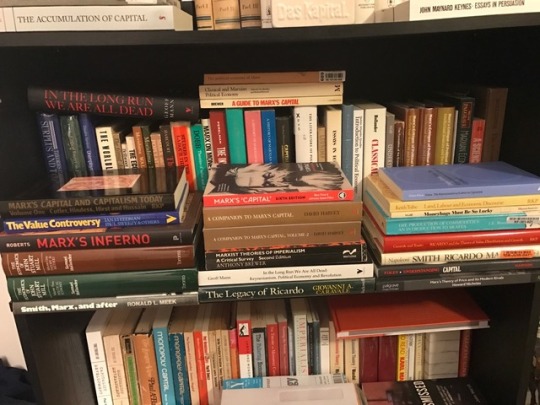

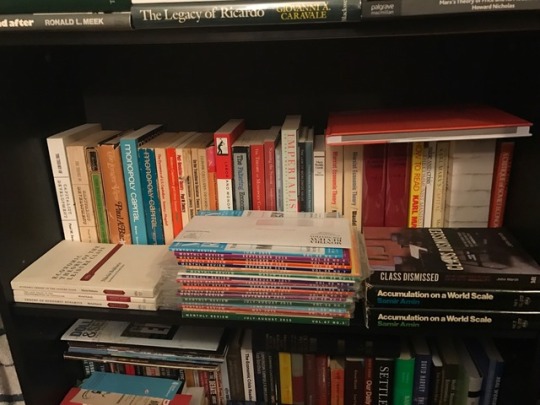

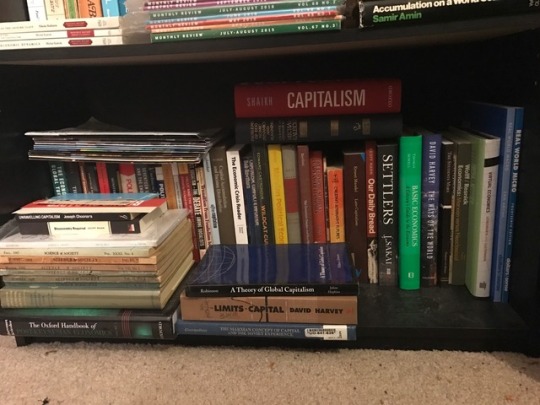

my economics bookshelf 1st shelf: primary economic literature (pre-classical, classical, neoclassical) 2nd shelf: primary economic literature (critical, keynesian, epiclassical) 3rd shelf: history of economic thought 4th shelf: monthly review books 5th shelf: general economic texts

22 notes

·

View notes