#eourpe

Photo

(via Harrison Cave in Barbados - Tour Discoveries)

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

WHY HE OURIPLE

1 note

·

View note

Text

okie okie yall pinky promised!! here is part one of the prologue of 'bovzek and the devil' and you are all required to read it. constructive criticism is encouraged bc im not used to this writing style and I'm still getting used to it. this is very much a first FIRST draft!!

some notes-- this is a dark fairytale esc story taking place around ~1000 AD in eastern eourpe in an imaginary country, Milan-Rosae. the folktale creatures are slavic in origin. tw for misogyny from the pov character, pregnancy, death during childbirth, talk of a baby dying from starvation (the baby does not die!), and a dude seriously having it out for a literal infant

enjoy!

Queen Wenzel was pregnant. Her stomach was swollen, her belly button poking out as stretchmarks made vines across the taut, cellulite-puckered flesh, like ivy creeping up brick. The baby--their baby-- kicked often, shifting beneath the skin of her belly, and Claudius took great pride in feeling the fluttering movement under the palm of his hand as he rested it on Wenzel’s stomach. Their boy (because it would be a boy, Claudius was sure of it) would be strong, with arms as mighty and unwavering as the kicks against the wall of its mother’s womb. Wenzel was due any day now, maybe even any hour. Drowsy spring stretched on outside the castle windows and Claudius could hardly contain his excitement, just as he could barely hold back the growing annoyance he felt towards his wife. Her vomiting, her crying, her whines of pain and backache as she grew larger, her once beautiful body now ruined with child, all grated on him like porcupine quills against fresh bark.

Wenzel and Claudius’ marriage hadn’t been born out of love, but instead a treaty between a rich walled kingdom that gnawed on the tail of the Roman Byzantine Empire, and Milan-Rosae, the heart of the East. Nestled between Pomerania, the fiercely held vassal of the Holy Roman Empire, and the Duchy of Bohemia, back before the Schism of 1212 split the world apart, Milan-Rosae was a place of beauty that, in Claudius’ opinion, rivaled no other. Surrounded by the Šumava, a towering roof of green spruce that clung against the sides of the Murmuring Mountains, and the Vydra, the Mighty Otter, a river that cut through the green and brought with it icy lakes and peat bogs, Milan-Rosae was protected from all. Queen Wenzel and King Claudius the VII had made a loveless marriage into a successful allegiance, one that would soon bear an heir, and Claudias awaited that day with bated breath.

Claudius shifted in his saddle. Technically, a royal hunt could have (and probably should have) been put off until Alois was born, but Claudius couldn’t spend another damn day with Wenzel. If he had to listen to his wife vomit all over her swollen belly again he might tear out what little hair he had left. He’d taken to having her sleep in a guest suite; Claudius couldn’t spend another night listening to her sniveling. No, what he needed was fresh air and the company of his men, not Wenzel’s displaced humors, and a hunt would provide just that. Wenzel had pitched a fit of course, as all women did, whimpering something about how she couldn’t be left alone when the birth was so close, and how frightened she was to pass the boy without a hand to hold, but frankly, Claudius had no intention of being there when she did pop his boy out. Too much blood and shit and organs. He’d much prefer his only memories of his wife naked be when he thrust himself in and filled her with his children, not when she was shitting and bleeding all over herself, thank you very much. As long as he could hold a baby boy soon, he was happy.

The royal hunt was supposed to be to find a great Azhdaya, deep in the forest, after which rClaudius and his men would take down the beast, a demonic wryn with three heads, and make a headboard for the newborn prince from its breastbone. In truth, Claudius was just ready to be alone in the wilderness and wild, with only his vassals and knights by his side, sword in one hand and bow in the other, his hounds gnashing their teeth and yanking on the lead as they smelled the air for the scent of dragon. Claudius was ready to let them loose, to swing his sword and spill blood; Wenzel, as beautiful as she was, was desperate to emasculate, constantly carrying on about the importance of kisses and gentle touches. Claudius did not approve of striking women-- he was a Godly man, after all-- but sometimes Wenzel’s nauseating need to be held at night after fucking tested him. Hopefully, the baby would provide an outlet for her, but until the baby came, Claudius needed an outlet for his pent-up frustration, and dragon hunting would do just that. The hunt called to him, whispering of glory and freedom, and Claudius was more than happy to answer that call.

Claudius clicked his tongue, and with a sharp flick of his reins, the horse moved forward. The spring had been mild, the Ride of the King untouched by heavy rain or wind, a sign of good to come. The festival and parade had been grand, and Claudius had been proud to sit above it all and watch the Pentecostal precession march by. May was nearly halfway through, and soon the breath of summer would blow across the treetops of the Šumava and turn the capital city into a sweltering pit of misery, but until then, Claudius enjoyed what was left over from the peaceful shower that had fallen yesterday. They turned the greenery of the forest a bright emerald, the plants soaking up the rain like a sponge did lye, and the ground was spongey with moss beneath his horse’s hooves. Mist and moisture hung in the air, the humidity almost uncomfortable as it sunk into his chest. Arnold rode in step with Claudius’ horse. The vassal was a good soldier, loyal and reverent with a touch of bloodlust that excited Claudius at every joust and hunt, and, had his family not been as brown-blooded as they came, Claudius would have called the man a friend.

“I smell a storm coming, my liege,” Arnold said, his horse walking a respectable five feet behind and to the left of Claudius’ own. He craned his head back to look at the towering spruces around them, and Claudius took a deep breath in. Yes, he could feel the weight of rain settling in his lungs. It was coming, and soon. Rainstorms meant the Vydra would swell, bringing with her all sorts of creatures, ones that Claudius would very much like to avoid. That was the downside of a forest as majestic as the Šumava. Poets had compared the spruces of Claudius’ forest to giants, creatures of wood reaching up with branches so that they might shake hands with God. With her protection, Claudius need not fear the Holy Roman Empire, nor Pomerania, nor the Duchy of Bohemia. Should the massive trees fail to deter invaders, then her tenants certainly would; after all, it wasn’t just bark and roots and tree nettles that could be found on the forest floor. No, the Šumava carried with it secrets-- grand, dangerous secrets.

Fae. Samojuda and Vila, Baždarica and Rusalka, even Vodník all made their homes amongst Claudius’ trees, on the banks of its river and lakes, up in the branches and down in unmarked graves. Father Michael would surely click his tongue and shake his head to hear Claudius speak of such things, but it was the simple truth. Strange creatures lived in the forest, with too-big eyes and too-long teeth, who spoke with gentle, booming voices. Claudius believed in the fae; it was foolish not to, and now, as they moved through the wet glittering spruces, the creatures felt close.

“Aye,” Gregory said in reply as Arnold repeated himself for the third time. Arnold had a nasty habit of jabbering, a little too fond of his own voice. In contrast, Gregory, the newest and youngest of his knights, was quiet and self-contained. He carried promise, if he’d simply harden his heart a tad. He was too kind, too mushy, and it would bite him in the ass sooner than later, and when it did, Claudius was not going to bail the man out of his troubles. “It reeks of lightning. Should we turn back, my Lord?”

Claudius hummed, peering up at the sky. The sky couldn’t open up, not now when they were so deep in the forest away from warmth and shelter. They hadn’t even heard a sniffle from the Azhdaya, let alone its roar, and Claudius had no desire to return empty-handed. That and, should it rain, his new doublet, a fine green thing that perfectly complimented the foliage, would be ruined by the mud, which would be an absolute shame.

“Give it an hour more,” Claudius said, giving his horse a slight squeeze with his knees and sending it off from a slow, steady trot to a canter. “If the sky darkens anymore, we shall turn back.” The two men nodded, turning in their saddles to repeat the order to the other vassals and knights present. The party pressed closer together and spurred on their horses, moving through the spruce like snakes through tall grass. Claudius was beginning to debate picking up the pace even more when, as if the sky had been waiting for the decision, the clouds split. The grey clouds had been deceptively small-- now, as the rain poured down, Claudius was quickly becoming sure this would be much more than a simple spring shower. Damn it.

Arnold swore, jerking his horse to a stop, with Gregory not far behind. A flash of lightning lit up the sky with a crack. Claudius jerked his horse back. Well, shit. The lightning had been close, dangerously so; they needed to turn around. Claudius turned to shout the order to Arnold when another pearl of lightning came down from the sky, striking a tree not even a hundred yards away in a spray of light and heat. The tree split with a scream, the sound almost drowned out by the thunder. It swayed once before tilting back, then forward; Arnold let out a shout, calling for Claudius, but the tree had already fallen, crashing to the ground between Claudius and his men. Claudius’ horse reared up in surprise, eyes wild and ears flattened, and Claudius struggled to grip its slick leather.

“Easy, beast!” Claudius yelled over the rain, jamming his heels into the horse’s sides. Instead of settling, the creature bolted. Clinging to it desperately, Claudius pressed himself close over the horse’s mane. Still delirious, the stupid beast leaped over the tree that was already taking flame and took off into the trees. Claudius could do nothing but grit his teeth and struggle to stay in his saddle as the horse wove through the trees. The forest had quickly become dark with rain, the sky now completely blanketed with clouds, the only light the blinding flash of lighting every few minutes. The horse squealed at a particularly large flash, rearing back and shaking its head, and the leather was too wet, the rain too thick, the spring air too electric—Claudius’ hands slipped from the reins and as the horse spun directions he was flung off, back into a tree, smacking his head against the bark, ripping hair and flesh as he tumbled to the ground. He didn’t have the time to think of his wife, of his unborn baby, even of Arnold or Gregory; he didn’t think at all before he crashed to the ground, still and dim as a snuffed candle.

---

When he woke, the forest was dark. Claudius pulled himself from the ground with a sound of disgust. Mud crusted his new doublet, thoroughly ruining it, and he was soaked to the skin. Moss clung to his beard and vines wrapped around his legs; it took an obnoxious amount of time to free himself from them. He spat out silt, struggling to right himself. The mud had sucked him down like a yearning lover, and with a grunt, he struggled to his feet.

The forest was silent. The rain had stopped. The sky was clear of clouds, but still black, the stars dim and the moon gone. There was no light in this night, no north star, and Claudius frowned as he brushed off his trousers.

“Arnold!” He yelled, turning in a circle, taking in the soaked trees. “Gregory!”

Nothing.

Fuck.

His men wouldn’t abandon him, of that Claudius was sure, and his idiot of a steed—which was now, of course, nowhere to be found—couldn’t have dragged him far. But it had been light when the rain started and now the sky was a black velvet blanket. Claudius was clueless as to how much time had passed. He sighed.

“Arnold! Gregory! I’m here!” He shouted, knowing the words wouldn’t travel far in the soaked moss of the forest. Still, he refused to let his growing concern enter his voice.

“Damn it all, you idiots, here I am!”

Nothing. Not a sound, not even the chirp of spring insects. Perfect silence. He could sit and wait, but then his trousers would get wet, and he was growing anxious. How far had the horse dragged him?

How far from home was he?

Suddenly, a low, mournful sound cut through the silence of the night, and Claudius’ heart skipped a beat. Wolves. He took a steadying breath. He had a sword and knew well how to use it, but one man against a pack of beasts was still unfortunate odds. He could climb a tree and wait the wolves out, but the thought of being surrounded by a pack throughout the night, perched precariously and shivering on high branches as they slobbered and panted, waiting out their hunger was terrifying. Claudius knew he was a strong man in good health, he was unsure how long he could hold himself up.

The mourning voices came again, louder, longer, closer, and Claudius’ well-thought planning left his mind entirely. He turned on heel and ran, breaking through the trees, water and mud sucking at his boots, spruce needles clawing at his face and ruined doublet, and Claudius knew that surly the wolves were just behind him, their foaming gums and teeth gnashing at his ankles.

(The wolves were, in truth, far from Claudius. They gave little thought to the king. After all, the lumberer had died today, her sweet breath gone and her gentle heart stopped. No longer would she run with wolves, no longer would she feed them the finest parts of the deer from her hand. No longer would she scare away hunters and clap in delight at the wolves’ song. The lumberer was gone, dead and cooling. The stars and moon had dimmed their lights in mourning, and the sky opened its clouds in her memory— even the fair folk that lived amongst the spruces wept for h. The lumberer had died and the whole forest hung its head.)

Claudius ran, his blood pounding in his ears. The trees clawed at him, and it seemed to Claudius that the whole forest wished to devour him. He pulled his riding cloak tighter around him in hopes it would somehow protect him from the creatures that stalked the trees at night, until he came stumbling into a clearing he did not recognize. And there, in the center, as if the spruces had politely moved to make just enough room for it, was a house.

House was clearly an overstatement—the wood was warped and swollen, the nails rusted, the door uneven and crooked on its hinges—but the late lumberer’s home radiated warmth, the kind that could never be found in a court or a castle. Piles upon piles of wood, somehow untouched by the rain, sat proudly by the side of the wall, ready to be cultivated into fine lumber, and a sprawling garden of all wonderous things took up the right wall of the home. Vines curled protectively around the pane-less windows. Claudius squeezed the rain and mud from his doublet, straightened the crown on his head, and knocked on the door, kicking the gunk from his boots on the edge of the welcome step.

Nothing.

He knocked again.

“I stand before you as King Claudius Rampars the VII of Milan-Rosae, King of this land and the Šumava forest, and demand you open your door.” He called. He could hear shuffling inside, and the sound of stifled cries, and huffed. How dare they not open when he called? Who did this idiot think they were anyway? He grabbed the doorknob and tested it—unlocked, and unlatched. Very well. If this was what he needed to do to make himself known, then he’d happily let himself in. After all, as king, every door belonged to him. Claudius, with little care of the coming consequences, flung the door open, and stepped inside.

A woman sat by the fire. Claudius immediately turned his eyes—it seemed she’d mistaken living alone for living in heathenry, and sat in just her skirts, her bare flat chest open for all to see, exposing creamy flesh and plump curves of fat that rolled across her hips. She hissed something in some barbaric, unfamiliar language and drew herself up, impossibly tall with clear, too-wide dark eyes and hair the color of starlight tumbling in rich waves down her back. She turned her eyes upon him, and at that moment a word was whispered deep in the back of Claudius’ head: samojuda. But that couldn’t be so. The samojuda, those beautiful women of another world, lived along the Otter, not in shacks in clearings where the closest water was a hand-dug well.

“What in the Great Hells do you think you are doing?” The woman spat. The power in her words raised the hair along Claudius’ spine, a fear he didn’t quite understand-- but then there came a soft sound and a wail from a box nuzzled close to the fire. The woman let out a pained gasp and rushed to the box on the ground, softly shushing it, before gathering up a bundle of wool and skin—a baby. Small, painfully small, no more than a day old, with tan olive skin and bare swirls of auburn, brown-red hair, face scrunched up near in pain as it (he?) screamed.

“Shh, shh, hush little one, all is well, Matka is here,” the woman whispered, bouncing him desperately, and Claudius waited for someone with milk-filled breasts to come from deeper in the home to feed the clearly starving child, but instead the woman just held him close, face pale and shaky, eyes wild.

“Well?” Claudius said, watching the baby’s shriveled up face, “Aren’t you going to feed him?”

“I… I can’t,” the woman said, painfully soft. “I’m not his birth mother. I have no milk to give.”

Claudius scanned the small home for the mother—there was the fire, a loft, and little else, and no mother in sight.

“Then where is she?” He asked and the woman flinched, clinging tighter to the baby.

“She’s dead. I—she was sick, I tried to stop the bleeding, but it all happened so fast, and, and…”

The woman buried her face in the bare chest of the baby. “I don’t know what I’m going to do without her,” she said softly, more to herself than him, “I can’t feed him. I’ve tried with a rag and some goat milk, but he won’t latch. Every child I’ve created from the forest I haven’t thought of for even a moment once I rid myself of them, but he… he has his mother’s eyes, I cannot… I cannot watch him die.”

The woman took a shuddering breath. “I wish he had died with his mother. At least then it would have been quick. Now he will starve, long and slow, and I can do nothing to stop it.”

Slowly, the baby quieted, and the woman’s eyes, glittering in her skull, softened. “My little boy…” she whispered, brushing a finger over his closed eyelid, “my precious little boy.”

Claudius shifted uncomfortably in the doorway.

“Does he have a name?”

The woman let out a bitter laugh. “Why bother? He’ll be dead in a few days.”

“Will he be baptized?”

The woman’s face twisted. “Absolutely not.”

“Why? You’re not some heathen in the woods, are you?” Claudius said with a scoff, and the woman turned her dark eyes to him, shining with something malicious.

“Watch your words, your majesty.” She spat, and Claudius took a step back without thinking too.

“I—”

“You speak to me of baptism? You know nothing of how this forest works, its history, its people, its magic. Nothing!” She said, taking a strong step forward, soon nose to nose with Claudius, her baby nearly pinned between them.

“Leave.” She said, “Leave this place. Forget me, forget the babe, go back to where you came from, king. You are unwelcome here.”

And then the baby began to cry. Weaker this time, quieter, less a wail and more a wrecked sob, and the woman swore, rocking him gently.

“Look what you’ve done.” She hissed, “Won’t you let us die in peace?”

Claudius’ mouth stuttered. “I—”

“Is it too much to ask for a creature and her baby to die, together and warm and unbothered?”

“Ma’am—”

“Don’t ma’am me when you barged into my home!”

The baby’s cries had become screams, and tears had begun to drip down the woman’s face, and Claudius’ insides shriveled. Never in his life had he seen a baby cry up close, and the scrunched flesh and watery eyes gutted him in a way nothing had before. His baby would look like this. His Alois, his son, his heir. Would he die too if Wenzel were to pass before she could hold him to her breast?

No. No, Wenzel wouldn’t pass, and even if she did, God protect her, Alois would have a wet nurse and a million men and women and court folk who would happily hold him to their breast. Alois would have everything, and this woman (Woman? Creature? Samojuda?) would have nothing.

“I am a king,” he said softly, and the woman’s face twisted with a sneer.

“Oh, truly?” She said mockingly, and Claudius held up a hand.

“Please, listen. I am a king—I have access to many resources and many pregnant and nursing nobles who would bend over backward to please me. If I asked, they would welcome your baby into their crest in an instant.”

The woman stopped, mouth hanging open. “I… are you…?”

“It is a generous offer, but one I am willing to hold myself to.”

The woman cradled her baby even closer to her chest. “You would?” She whispered, and Claudius felt himself nod, not even sure he was doing so.

The woman took a step back. Between them, the baby had quieted. She walked back to the fire and slowly sunk down to the box, sitting on its edge, and began to hum. Claudius found himself entranced by her song, her sound, like sweet dew and warm sunlight, and a deep breath after a dip in cold water. She waved him over and slowly, he moved to her side and sat beside her.

“What was the mother’s name?” He asked softly, and the woman took his hand, guiding it to the baby’s head. Claudius wondered at his wispy hair, his dark eyes, and the baby smiled at him. Claudius smiled back.

“She was a lumberer,” The woman said, “She wooed me with little carvings and statuettes, carved them till her hands bled and left them for me to find until I fell in love with the little things and then, slowly, with her. She was beautiful, with skin like an oak leaf, hair like a river, and eyes like starlight. She loved the world unabashedly, loved the wolves and the buzzards and the worms as much as she did the flowers and the larks. She was my little lark. She… she always had a long on her lips, and we joined in bed together, so ready to raise a little one… We were overjoyed when she became fat with child.”

The reverent look on her face faded, replaced with a bitterness that made Claudius shiver. “She grew pregnant, that’s for sure. Then sick, and then bloody, and then dead.”

“My wife, she is with child, too,” Claudius said. “A boy, I’m sure of it, and I will name him Alois, after the mighty warriors, so he will grow to be strong and unbreakable.”

“Strong and unbreakable,” the woman said softly, “isn’t that a wonderful thought? Maybe my boy will be the same. Will you, beloved? Will you be strong and unbreakable?”

The baby gurgled up at them. Claudius was struck with a sudden warmth despite the chill of his wet clothes and couldn’t tear his eyes from the boy. He was perfect in every way, with his olive skin, dark eyes, and auburn red hair.

“He shall be,” Claudius said, and the softness in his chest scared him. Claudius was not a soft person, but beside this baby, his heart felt as mushy as a rotten apple, as sweet as sugar syrup. He felt… weak before this baby, and for a moment a stalk of fear struck him. How could something so small be so powerful? It was almost… otherworldly. Claudius glanced at the baby’s mother and her too-big eyes, her pale hair, her unashamed half-nakedness. What kind of woman was this, alone in the woods with a lumberer as her only company? Who was she, to be so content without civilization, so without civility that she’d sit without anything to cover her chest while before a man, a king? Was her lumberer just as uncivilized?

The baby’s eyes had slipped shut, and the woman ran fingers across his tan cheeks.

“Sleep, worldly king,” She said. “Take the spot by the fire. My boy and I shall take the loft. Enjoy the warmth, and dry yourself. We shall leave early in the morning for your kingdom.”

Claudius perked at that. “You can take me home?”

“Aye. I know these woods better than any else. I can take you to the forest’s edge where the walls that surround your kingdom are. A walled kingdom with a walled capital. How strange—are the bricks to keep all out, or all in?”

Claudius pursed his lips. “The Holy Roman Empire--”

The woman waved a hand. “I have no care for petty human politics. You all die in the end.”

“And you do not?”

The woman looked to Claudius with faraway eyes and gave no answer. Claudius shuddered.

“Take the spot by the fire,” The woman said again, and Claudius nodded without even thinking too. The woman bundled the baby to her chest and moved deeper into the home to the loft, murmuring to the child and not giving Claudius a second glance. Claudius sat, bewildered, and finding he couldn’t speak as he watched the bare back of the woman (samojuda, samojuda, samojuda…). He found his thoughts tumultuous and tangled. The fire couldn’t seem to calm them.

He knew then he would never be able to sleep.

Still, Claudius curled up on the fur on the floor, close to the hot coals, and closed his eyes. He’d take the boy in the morning, but until then… until then he would share a home with a fae and the spring storm howling just outside the pane-less windows.

---

Claudius woke slowly, his eyes heavy and his mouth foul tasting, and furrowed his brow. Something low and melodic drifted through the air, and he sat up. Someone was humming. Claudius slowly stood. It was likely the woman, spending as much time cradling her baby as she could before she lost him forever. Claudius approached the ladder to the loft, ears perked, as the woman stopped humming and began to sing in a low, husky voice, heavy and thick with magic. Claudius felt gooseflesh ripple across his skin at the sound of it. It was heavy with power, and Claudius knew in that moment that this woman was far from mortal. The word ‘samojuda’, that beautiful forest spirit, echoed in his head.

Samojuda, samojuda, samojuda…

He stepped up on the first rung of the ladder and strained his ears as the samojuda continued to speak.

“My sweet, brave little boy," the samogude sang to the baby, "Before you leave me forever, I call upon the Fates to bless you and keep you. I ask they give you the gift of creation. May a love for making something out of nothing temper your heart into shining steel. I ask they give you the gift of compassion- may you be just and good to all men.”

The samojuda took a deep, shaky breath, and Claudius could hear love and despair in it.

“Little one… I ask they give you the gift of love, true, deep love, like that of your mothers’. May you find love that never wavers or breaks. May you be loved by great things— may you live lavishly and be loved by someone greater than all else, who can spoil you as much as they adore you. May you… may you love and be loved by a child born to a king!”

The humming returned, the samojuda done with her song and content to simply rock her baby. The creature’s words were shrill in Claudius’s ears.

A child born to a king.

Claudius dropped down the ladder and sunk to his knees. The boy… he was not some starving lumberer’s child. He was a child of a samojuda, and a beloved one at that. This fae women were known for their changelings, for thrusting babies onto unsuspecting parents and drowning the couple’s original children. For a samojuda to wish to keep a child, to protect it… It was unknown, unfathomable, and spoke of terrifying power. The fae had great influence over the Fates, and if those holy women decided something, it was as good as sealed. That damn samojuda, should the Fates follow her wishes, had just damned a king’s child to a wretched fate. To marry a lumberer’s child… Claudius' heart twisted with disgust at the thought of some half-blooded creature marrying into a court.

It was a bastardization of nature, for something so tainted by inhuman blood and poverty to even look upon a king’s child, let alone touch one, love one, breed with one. Claudius couldn’t let that happen. He couldn’t condemn some poor royal to that fate. If something like that were to happen to his own son. The though made Claudius pause. If he took this creature into his court, right after the birth of his own son, his own heir, the chances that... His stomach rolled, and he pressed a hand to his mouth. He couldn't allow it. He wouldn't damn his unborn child to such a life. Fuck promises made, fuck agreements, that child could never step foot in a court. Never.

Claudius would protect his child from such a monstrous fate; the only question was how.

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

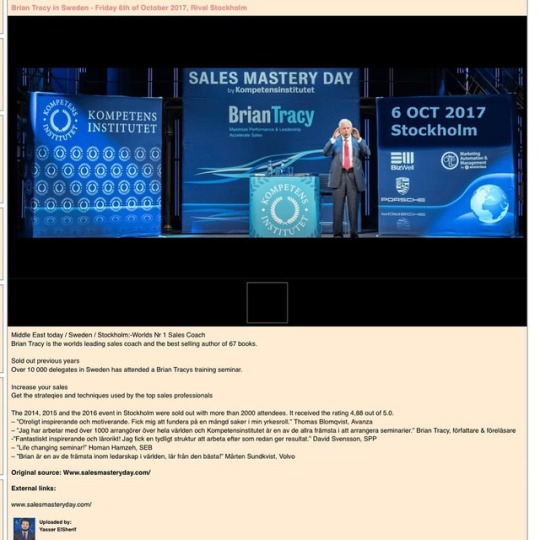

#braintracy #sales #leadership #development #human_resources #eourpe #middleeast (at Sweden)

0 notes

Text

eourp

shoudl i just fuckin

drank all these potions at once or wait

i dunno if itd b a good idea or if id like explode

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

artificersgrievance replied to your post: eourp shoudl i just fuckin drank all these potions...

Yes. For science.

VOTES ARE IN ITS TIME TO HAVE A TIME

1 note

·

View note