#english miniaturist

Text

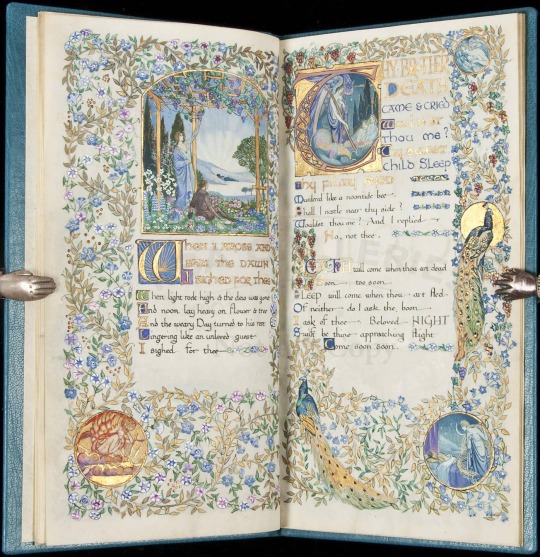

“To The Night & The Cloud” by Percy Bysshe Shelley (1792-1822)

1914

Artist : Jessie Bayes (1876-1970)

Source : pbagalleries.com

#jessie bayes#english artist#english miniaturist#illuminated manuscript#calligraphy#calligraphic text#vellum#manuscrit#calligraphie#percy bysshe shelley#miniature#floral design#botanical design#animals#mermaids#fish#boat#night#cloud#rainbow#angels#peacock#poem

3K notes

·

View notes

Photo

MINIATURIST, English

Troy Book and Siege of Thebes by John Lydgate

1457-60

Manuscript (MS Royal 18 D. II.)

British Library, London

163 notes

·

View notes

Text

George Engleheart, English miniaturist.

Inscribed in ink on the backing card 'Napoleon. / First Consul.'

I don't know whether the artist saw Napoleon in person.

christies

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Flowers Bloom Regardless

Flowers Bloom, Regardless

https://ift.tt/0elNvaB

by miniaturist

Pansy Parkinson has returned to England, against her better judgment. It's been six years since she left her family and best friend behind, during a period of her life she doesn't like to dwell on. At the encouragement of her best friend, Luna Lovegood, she decides to take a job at Hogwarts caring for some of the magical creatures that live there. Her return to England is anything but smooth, inciting flashy newspaper headlines, flareups of old wounds, and the ire of one Hogwarts Herbology professor. But Pansy refuses to let anyone control her life anymore, except for her.

Words: 3114, Chapters: 2/?, Language: English

Fandoms: Harry Potter - J. K. Rowling

Rating: Mature

Warnings: No Archive Warnings Apply

Categories: F/M

Characters: Pansy Parkinson, Neville Longbottom, Hermione Granger, Luna Lovegood, Draco Malfoy, Harry Potter, Daphne Greengrass, Astoria Greengrass

Relationships: Neville Longbottom/Pansy Parkinson, Hermione Granger/Draco Malfoy

Additional Tags: Harry Potter Epilogue What Epilogue | EWE, Post-Hogwarts, Romance, Herbology Professor Neville Longbottom, Professor Luna Lovegood, Mental Health Issues, Past Child Abuse, Substance Abuse, Lesbian Luna Lovegood

via AO3 works tagged 'Hermione Granger/Draco Malfoy' https://ift.tt/dyqWwRK

March 09, 2024 at 09:51PM

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

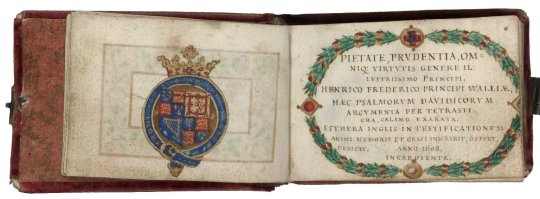

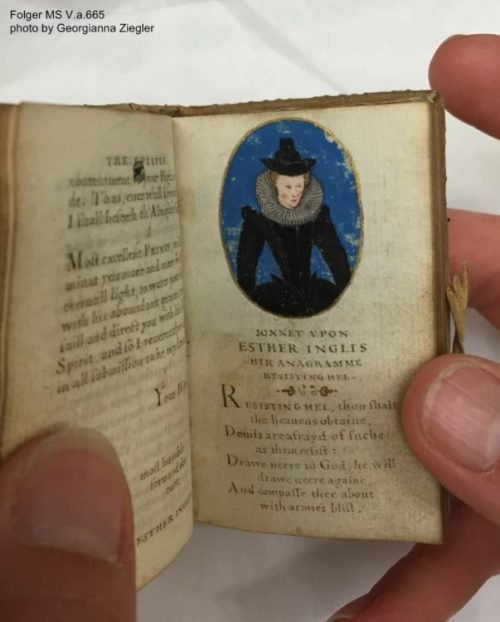

August 30th 1624 saw the death of Esther Inglis, calligrapher and miniaturist.

Esther Inglis, daughter of a French immigrant, was a celebrated calligrapher. She produced exquisitely illuminated documents and little books, illustrated with flowers. Her parents, Nicolas Langlois and Marie Presot, were French Huguenots who took refuge in England in about 1569, later settling in Edinburgh. Their daughter Esther seems always to have used the surname ‘Inglis’, the Scottish form of Langlois.

In 1596, Esther married Bartholomew Kello, and by 1604 had moved with him to London. They had six children, of whom four lived to adulthood. Kello, a clergyman, had a church in Essex between 1607 and 1614. In 1615 the family returned to Edinburgh.

Esther went on to become an exceptionally skilled calligrapher (calligraphy is the design and execution of decorative handwriting), illustrator and embroiderer. Her manuscripts vary from religious texts and psalms to secular (non-religious) works - which Inglis transcribed - to designs for emblems (symbolic pictures) and heraldic arms.

She often dedicated her manuscripts to members of the Elizabethan and Jacobean court, and high-ranking European protestants. Often presented as gifts in diplomatic exchange, it is believed that Inglis's early works may have been used to support the negotiations leading up to James VI’s accession to the English throne.Inglis was multilingual and wrote in Latin, Scots and French. From 1599 her manuscripts, which are miniature in scale, also include tiny self-portraits which promoted her authorship and talent. These images are the earliest known self-portraits by a female artist working in Britain.

Her intricate illustrations often feature animals, flowers and fruit, and Inglis may have used emblem books (books of symbolic pictures often accompanied by mottoes, morals or poems) as a source of inspiration for her designs. Inglis was multitalented and she also embroidered her bound manuscripts, using precious metal threads and seed pearls (tiny natural pearls less than 2mm in size) on velvet. Her works transcend the traditional boundaries of text, visual and textile art forms, and as such she occupies a unique place in European and Scottish renaissance culture.

Despite her talent and prestigious clients, by her death Inglis had accrued significant debts. She died in Leith in August 1624, the dates differ a wee bit.

Today around sixty of her surviving works are recorded in public and private collections across the world. Some of the most decorative and accomplished works can be found in the National Library of Scotland, the Royal Collection Trust and the Folger Shakespeare Library in Washington, D.C.

The portrait of Esther Inglis can be seen at the Scottish National Portrait Gallery as part of our Reformation to Revolution display.

The University of St Andrews purchased some of her work over ten years ago, you can learn more about her and view some of the pics at the link below.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Read-Alike Friday: The Swift and the Harrier by Minette Walters

The Swift and the Harrier by Minette Walters

Dorset, 1642. When bloody civil war breaks out between the king and Parliament, families and communities across England are riven by different allegiances. A rare few choose neutrality. One such is Jayne Swift, a Dorset physician from a Royalist family, who offers her services to both sides in the conflict. Through her dedication to treating the sick and wounded, regardless of belief, Jayne becomes a witness to the brutality of war and the devastation it wreaks. Yet her recurring companion at every event is a man she should despise because he embraces civil war as the means to an end. She knows him as William Harrier, but is ignorant about every other aspect of his life. His past is a mystery and his future uncertain. The Swift and the Harrier is a sweeping tale of adventure and loss, sacrifice and love, with a unique and unforgettable heroine at its heart.

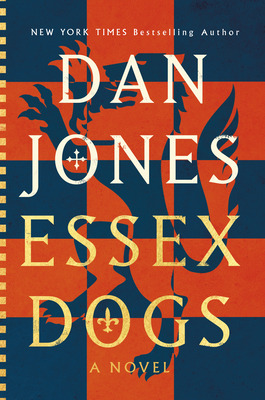

Essex Dogs by Dan Jones

July 1346. Ten men land on the beaches of Normandy. They call themselves the Essex Dogs: an unruly platoon of archers and men-at-arms led by a battle-scarred captain whose best days are behind him. The fight for the throne of the largest kingdom in Western Europe has begun.

Heading ever deeper into enemy territory toward Crécy, this band of brothers knows they are off to fight a battle that will forge nations, and shape the very fabric of human lives. But first they must survive a bloody war in which rules are abandoned and chivalry itself is slaughtered.

Rooted in historical accuracy and told through an unforgettable cast, Essex Dogs delivers the stark reality of medieval war on the ground - and shines a light on the fighters and ordinary people caught in the storm.

This is the first volume in the "Essex Dogs" series.

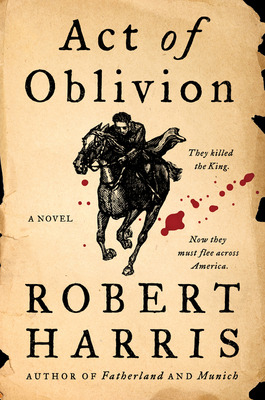

Act of Oblivion by Robert Harris

'From what is it they flee?'

He took a while to reply. By the time he spoke the men had gone inside. He said quietly, “They killed the King.”

1660 England. General Edward Whalley and his son-in law Colonel William Goffe board a ship bound for the New World. They are on the run, wanted for the murder of King Charles I—a brazen execution that marked the culmination of the English Civil War, in which parliamentarians successfully battled royalists for control.

But now, ten years after Charles’ beheading, the royalists have returned to power. Under the provisions of the Act of Oblivion, the fifty-nine men who signed the king’s death warrant and participated in his execution have been found guilty in absentia of high treason. Some of the Roundheads, including Oliver Cromwell, are already dead. Others have been captured, hung, drawn, and quartered. A few are imprisoned for life. But two have escaped to America by boat.

In London, Richard Nayler, secretary of the regicide committee of the Privy Council, is charged with bringing the traitors to justice and he will stop at nothing to find them. A substantial bounty hangs over their heads for their capture—dead or alive...

The Miniaturist by Jessie Burton

"There is nothing hidden that will not be revealed . . ."

On a brisk autumn day in 1686, eighteen-year-old Nella Oortman arrives in Amsterdam to begin a new life as the wife of illustrious merchant trader Johannes Brandt. But her new home, while splendorous, is not welcoming. Johannes is kind yet distant, always locked in his study or at his warehouse office--leaving Nella alone with his sister, the sharp-tongued and forbidding Marin.

But Nella's world changes when Johannes presents her with an extraordinary wedding gift: a cabinet-sized replica of their home. To furnish her gift, Nella engages the services of a miniaturist--an elusive and enigmatic artist whose tiny creations mirror their real-life counterparts in eerie and unexpected ways . . .

Johannes' gift helps Nella to pierce the closed world of the Brandt household. But as she uncovers its unusual secrets, she begins to understand--and fear--the escalating dangers that await them all. In this repressively pious society where gold is worshipped second only to God, to be different is a threat to the moral fabric of society, and not even a man as rich as Johannes is safe. Only one person seems to see the fate that awaits them. Is the miniaturist the key to their salvation . . . or the architect of their destruction?

This is the first volume of the "Miniaturist" series.

#historical fiction#fiction books#reading recommendations#readers advisory#library books#reading recs#book recommendations#book recs#tbrpile#tbr#to read#booklr#book tumblr#book blog#library blog

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Unveiling the Enchanting History of Miniature Gardens

This blog post will uncover the history of a world where imagination intertwines with nature, where miniature landscapes come alive with magical beings. You will learn about the origins of these lovely little landscapes that capture the imaginations of young and old alike! Miniature gardens and fairy gardens have captivated our hearts for centuries, allowing us to create whimsical realms in small-scale settings. Join me on a journey through time as we explore the fascinating history and timeline of these enchanting natural creations made by history’s miniaturist pioneers!

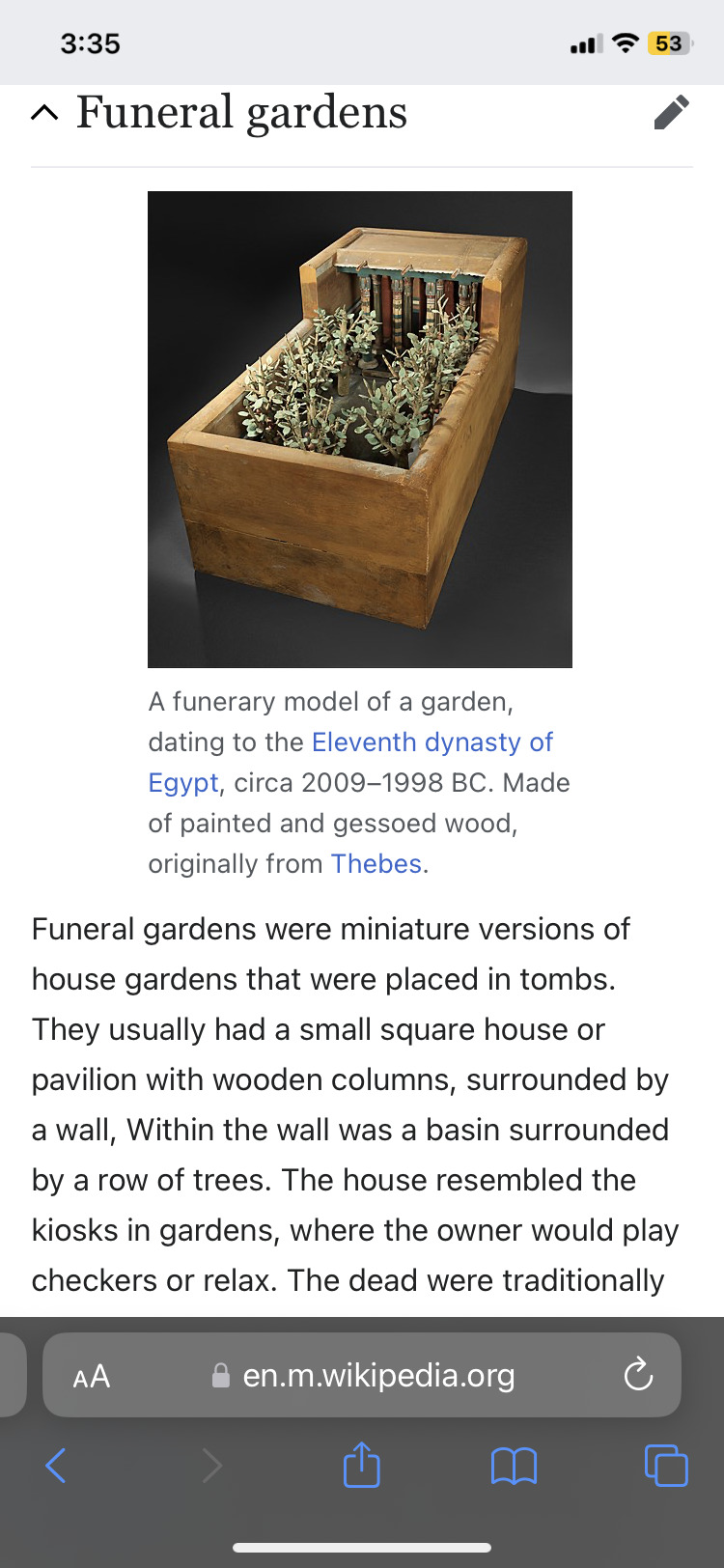

Miniature Garden Origins:

Ancient Egypt

Miniature gardens originate as far back as ancient Egypt, circa 2009- 1998 BCE. Within the walls of Egyptian tombs, the concept of these tiny gardens first took root. Known as "funeral gardens," these miniature container garden models were left by loved ones in ancient tombs for the souls that have passed to continue to enjoy their gardens in the afterlife. You can read more about ancient Egyptian gardens here on Wikipedia.

Penjing /Penzai/ Bonsai- A Brief History of Miniature Potted Trees (China- 600 AD)

Bonsai trees are the oldest known potted miniature plant practice ever recorded throughout human history! They originate from ancient China.

Read more about container gardening here.

Here’s an excerpt from Bonsai Empire below explaining some deeper history of the practice of bonsais, container gardens, and miniature rockery landscape practices.

Garden Gnomes- Germany’s First Fairy Gardens

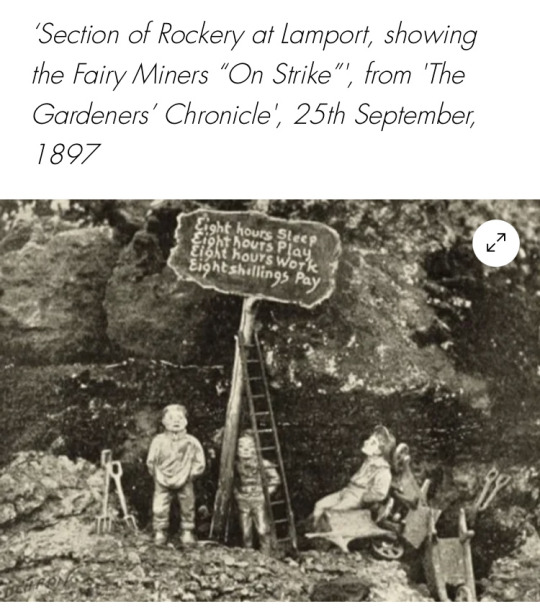

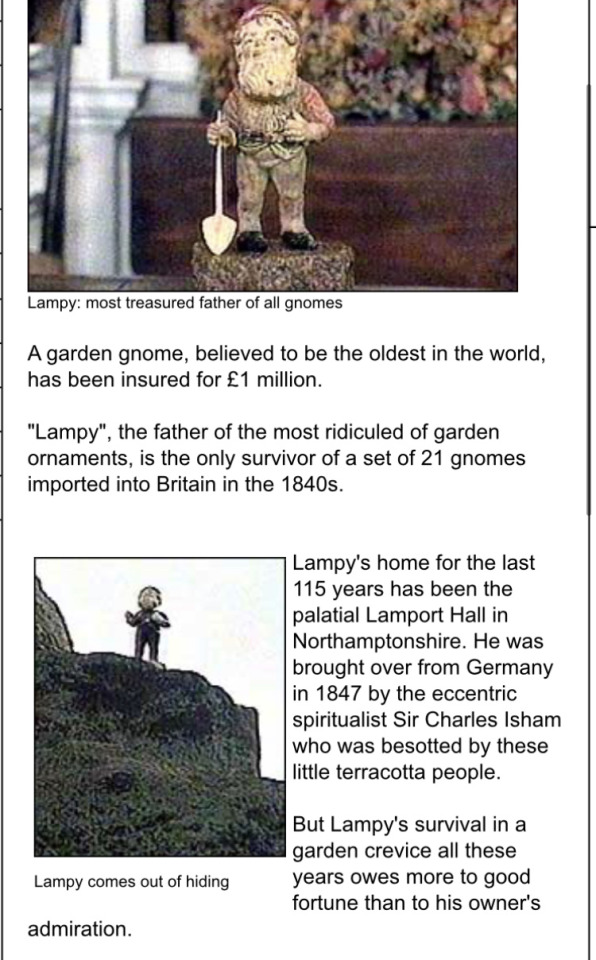

In the 19th century, Germany embraced the allure of miniature gardens with a magical twist. Garden gnomes began popping up in Europe as early as the 1600’s , and became quite popular in Germany by the mid to late 1800’s as their magical presence brought whimsy and wonder to the country. Unfortunately, WWII left many vintage German garden gnomes in ruins, making them extremely rare and valuable today! Read more about the history of vintage ceramic garden gnomes in this screenshot below.

English Rockeries - Rock Garden Origins

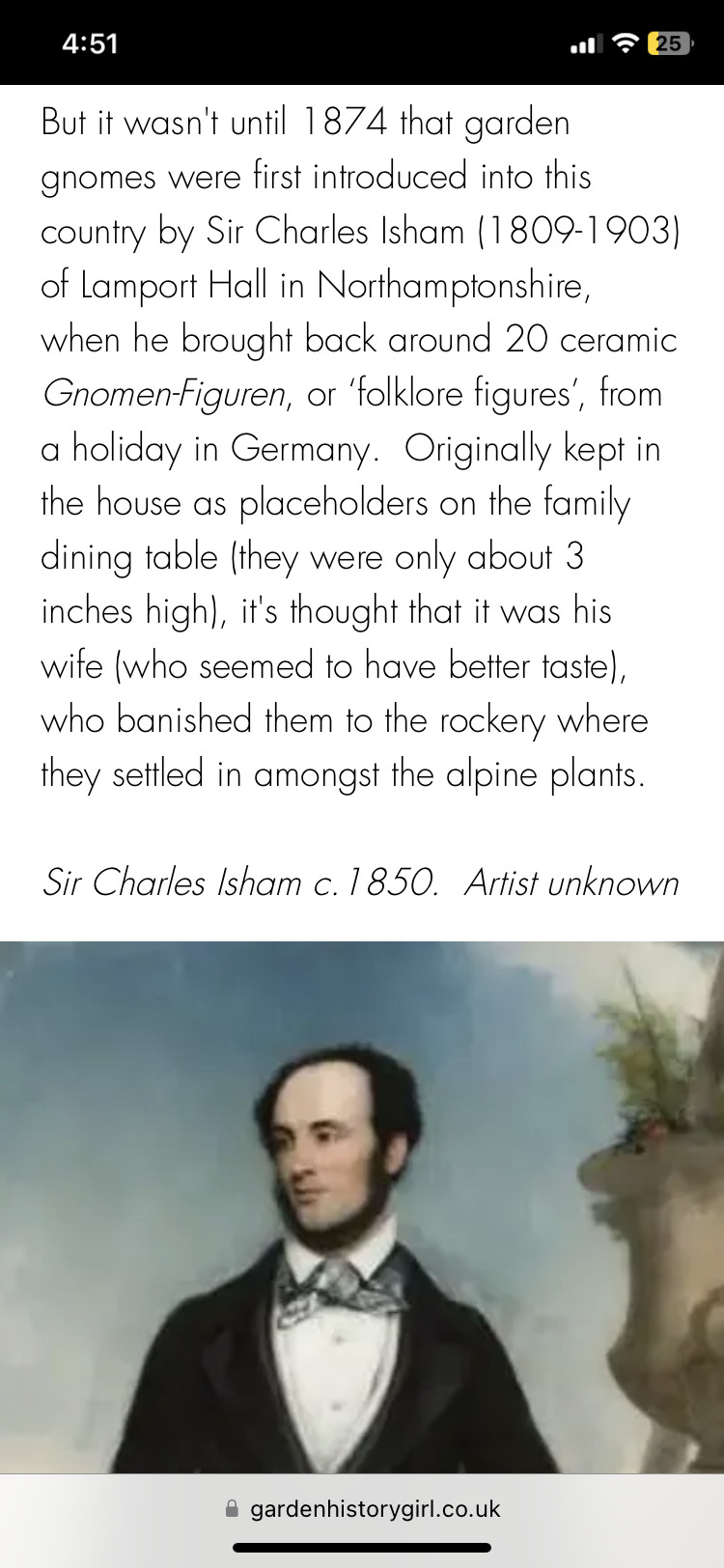

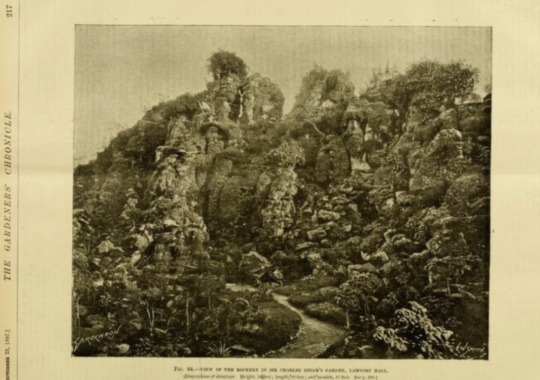

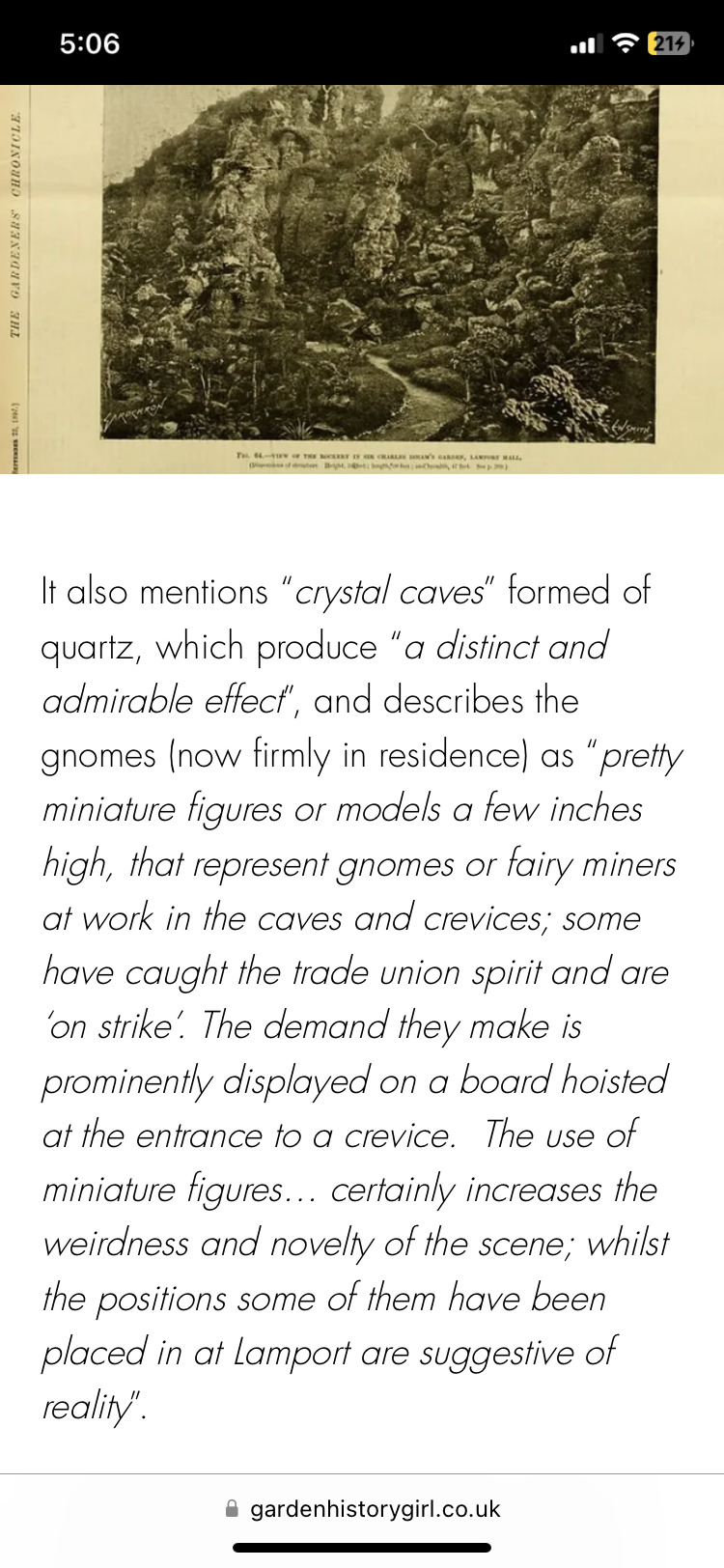

Across the English landscape, another facet of miniature garden artistry emerged during the 19th century—the rockeries. These intricate displays featured natural or artificial rock formations, often enhanced by small structures, figurines, and carefully chosen plants. While not explicitly tied to fairy themes, rockeries served as stepping stones towards the magical realms that would capture our collective imagination with today’s fairy gardens!

The earliest documented “fairy garden” would be in 1847 in England when Sir Charles Isham’s wife banished his miniature German garden gnome figurines to the rockery garden after not wanting them in the house! Read more at this link.

Pictured below is an image from Sir Charles Isham’s rockery featuring his little figurines in 1897.

After his death, Sir Charles’ daughters removed all the gnomes as they were not too fond of them, however, during a renovation or the rockery, one remaining gnome was found, who is now named Lampy and preserved inside the estate to this day!

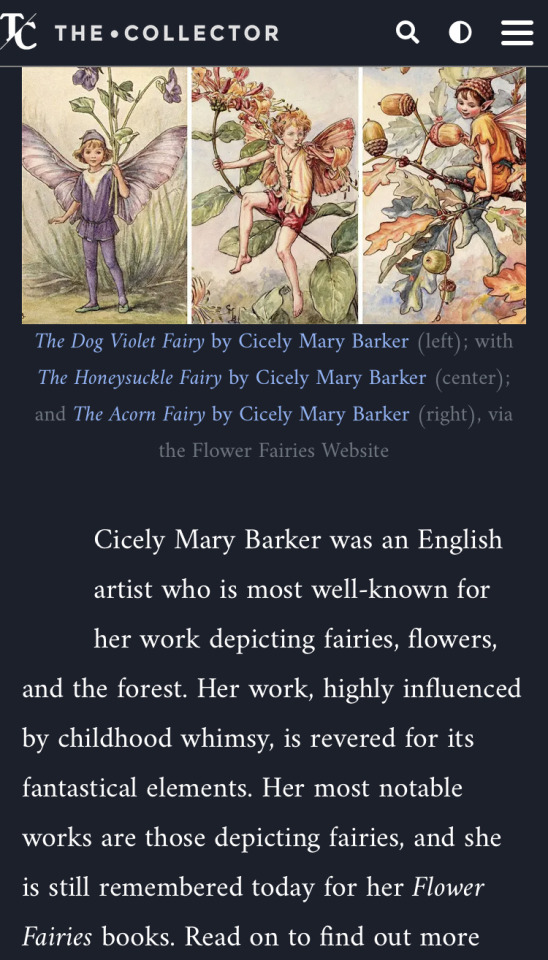

The Arts and Crafts Influence

As the late 19th century transitioned into the early 20th century, the Arts and Crafts movement swept across Europe, bringing with it a rekindled interest in folklore and nature-inspired designs. Creators and authors such as Sir Arthur Conan Doyle and Cicely Mary Barker embraced fairy themes in their works, stoking the flames of fascination for fairies, gnomes, elves and all the fae folk!

A Global Phenomenon

With the internet and social media platforms, fairy gardens have transcended borders, cultures, and languages throughout human history! Fairy garden enthusiasts and miniaturists alike, from every corner of the globe, came together to share their mini wonders, fueling a vibrant and supportive community. You can find a wide variety of communities that crossover between fairy gardens, gardeners, bonsai practitioners, miniaturists, doll artists, toy photographers and more! In my experience, I’ve found a huge community of toy and miniature photographers, artists, and fairy garden lovers on Instagram, Facebook, YouTube, and Pinterest! (I’m thinking about checking out DeviantArt next!)

From ancient Egypt’s funeral gardens and the ancient practice of Chinese bonsai, to the rockeries of Victorian England, and the whimsical garden gnomes of Germany; the history of miniature gardens and fairy gardens reveals a timeless enchantment. These miniature realms offer a space for creativity, imagination, and a connection to the natural world.

As we conclude our exploration of the captivating history of miniature gardens and fairy gardens, we can't help but wonder about the future of these enchanting tiny worlds. The beauty of miniature fairy gardens and landscapes lies in their infinite potential for uniqueness and timelessness.

Looking ahead, we envision a world where fairy gardens become even more personalized and tailored to individual stories and dreams. With advancements in technology, we may witness the integration of miniature automation, bringing movement and interactivity to these tiny realms. Imagine fairies fluttering their wings, miniature fountains and irrigation systems gushing with water, and tiny LED lights twinkling like stars in the garden at night.

To make your fairy garden truly unique and timeless, consider incorporating elements that reflect your personal passions and interests. Whether it's a miniature replica of your favorite bookshop, your favorite childhood toy, a mini herb garden inspired by your love for cooking, or a whimsical miniature treehouse that evokes childhood memories, infuse your miniature world with fragments of your own story, and you’re bound to have a lifetime of stories to build in your very own fairy garden!

Don't be afraid to experiment with different materials, textures, and plant varieties to create a harmonious blend of nature and imagination. Seek inspiration from literature, mythology, and cultural traditions to add depth and symbolism to your miniature garden. Remember, the most extraordinary fairy gardens are the ones that evoke emotions, tell stories, and transport us to a realm where dreams come alive.

While we marvel at the history behind the wondrous hobby of miniature and fairy gardens, it is the future that holds the promise of even greater wonders. So, let your imagination fly, embrace the beauty of nature, and embark on a journey to create a miniature world that is uniquely yours. As you sculpt, plant, and arrange, remember that fairy gardens are not just whimsical decorations; they are portals to our imagination, connecting us to the magic that resides within our hearts.

So, dear reader, why not embark on your own fairy garden journey? Unleash your creativity, let your imagination soar, and uncover the magic that lies within the tiny wonders of miniature fairy gardens.

We hope you've enjoyed this magical stroll through fairy garden history, May your own fairy garden be a testament to the enduring allure of these miniature realms, reminding us that dreams can come alive in the palm of our hands.

ADHDalex the FairyFindr //

Marvelous Magical Miniatures @marvelousmagicalminiatures on Instagram and Facebook for my Fairy Gardens, Miniatures, and Custom Dolls content

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

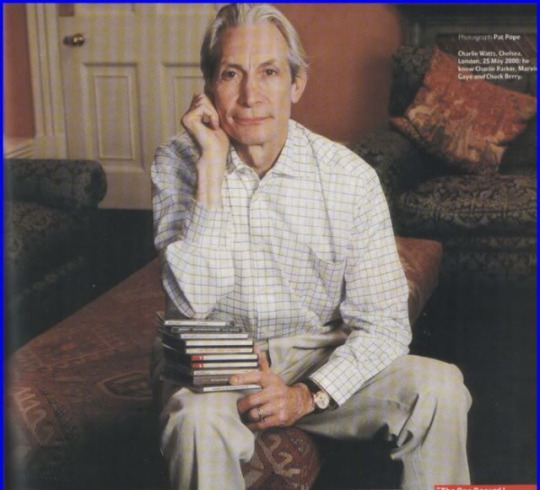

Top 5 early 2000s Charlie pics (so shameless of me, I just want to see pics). Also top 5 books.

I’m not complaining.

In no particular order:

1. He looks like a classic movie star and I love it.

2. Charlie smiling is nice no matter what, but I know from the rest of the set that he’s smiling at Mick, which makes it that much better.

3. I mean, do we even need to say why?

4. It’s neat to see Charlie in a space that he decorated, and it’s especially nice to see him looking so relaxed and comfortable in his own skin. This is 2000, so that good period post-‘80s drinking/drugs and pre-cancer, when he seemed to have more confidence than he ever had before or would again.

5. Isn’t it lovely to see an old married couple that still enjoys each other’s company?

I’m not sure if this is for the Stones or all books in general, so I’ll just do both.

(With the caveat that I’m a massive book nerd and asking me to pick my favorite is like asking someone to choose a favorite kid, so I’m just going a bit randomly and only doing fiction. Also, as before, no particular order).

Stones:

1. Life by Keith Richards

It’s biased, but he’s entertaining as hell/so damn bitchy, and there is Charlie propaganda galore.

2. The True Adventures of The Rolling Stones by Stanley Booth

An interesting view into the Stones as a cultural force, as well as their band dynamics, and Stanley’s obvious crush on Shirley is hilarious.

3. Sympathy for the Drummer by Mike Edison

Quite honestly, I don’t read a lot of band books/celebrity bios, and a lot of that has to do with the fact that the writing is trash. Totally not the case here. Edison has a very Hunter S. Thompson meets Tom Wolfe, gonzo/New Journalism style that makes the book enjoyable to read even just for the prose. Of course, the most important part is that it’s all about why Charlie Watts is amazing.

4. S.T.P. by Robert Greenfield

Like the Booth book, a cool view into the band itself and its cultural impact. The book he wrote about following them in 1971 is also pretty good.

5. Stoned by Jo Wood

Lots of great, candid photos.

Books in general:

1. My Name is Red by Orhan Pamuk

This is a novel about a miniaturist in the 16th century Ottoman Empire, but it’s also an exploration of religion, love, sex, violence, art, and everything else under the sun. The subject is already close to my heart, both because Islamic miniature painting is an art form I love and that period/place intersects with my professional life, but the prose is mind bendingly good. Each chapter has a different narrator, and it’s not only people that narrate, but the color red, a corpse, death, etc.

2. Brideshead Revisited by Evelyn Waugh

Waugh is one of my favorite English novelists, and this may be my favorite one of his books. It’s sweeping yet still human, sad but still retains hope, funny and dark without losing any of its gravity. The description of Charles and Sebastian under the tree with Aloysius the teddy will haunt me forever.

3. The Collected Poems in English: Joseph Brodsky

Poetry is a little outside of fiction, but I adore Brodsky, so we’ll stretch. To be quite honest, I’m guessing that this is the best resource to read him in English, because I have all of his work in Russian, but please, read him any way you can. He’s criminally underappreciated outside of the Russophone world, and his work is just shatteringly amazing. If you’ve never tried anything by him, look up “May 24, 1980.”

4. Love in A Fallen City and Other Stories by Eileen Chang

This is a novella attached to a collection of short stories, and every piece deserves to be written. Chang shines a fascinating light on early 20th century Chinese culture and society, normally from an often little appreciated female perspective. Even though many of her works focus on relationships between men and women, she’s not any kind of stereotypical romance writer, and you get a lot more than cheap tears or saccarine happy endings.

5. Love in the Ruins by Walker Percy

It’s the voice that draws me to this book, and I think that’s also what makes it so engaging. Dr. Thomas More (descendant of the famous author of Utopia) is a southern doctor struggling day to day to look after his patients in a disintegrating country. He’s also an alcoholic, a lapsed Catholic, and a divorcee who lost a daughter and ricochets between women trying to find stability and meaning while waiting for the end of the world.

#honorable mention for ada by vladimir nabokov#thanks!#the rolling stones#charlie watts#keith richards#old married band#mick jagger#ask response#anonymous#ask game

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

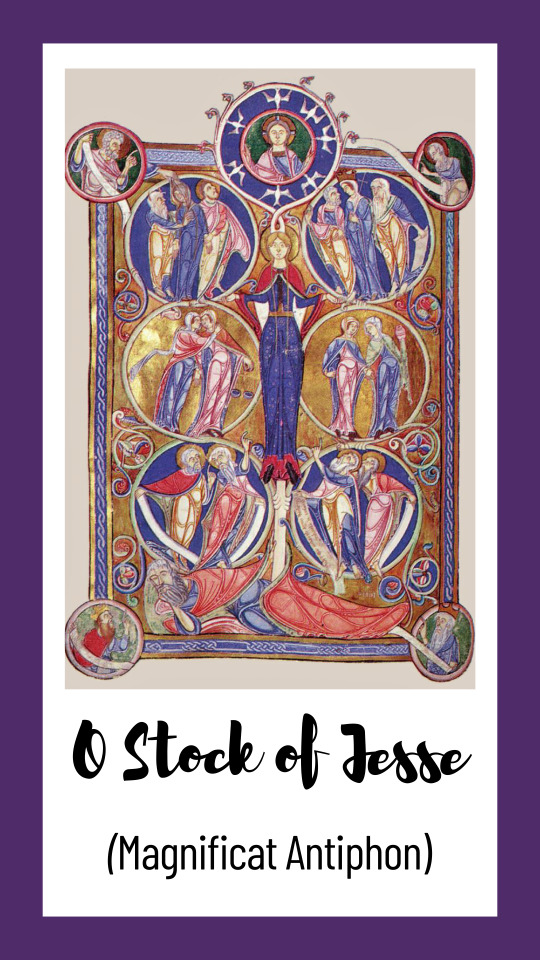

"O Stock of Jesse, you stand as a signal for the nations; kings fall silent before you whom the peoples acclaim. O come to deliver us, and do not delay." - #MagnificatAntiphon #TheChristmasNovena

📷 The Jesse Tree in the Lambeth Psalter (ca. 1140) by unknown English Miniaturist / #Wikipedia (PD-Art). #Catholic_Priest #CatholicPriestMedia #Advent2022

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

0 notes

Text

A Girl, formerly thought to be Queen Elizabeth I as Princess, 1549, attributed to Levina Teerlinc © Victoria and Albert Museum

Levina Teerlinc (1510s – 23 June 1576) was a Flemish Renaissance miniaturist who served as a painter to the English court of Henry VIII, Edward VI, Mary I and Elizabeth I. She was the most important miniaturist at the English court between Hans Holbein the Younger and Nicholas Hilliard. Her father, Simon Bening, was a renowned book illuminator and miniature painter of the Ghent-Bruges school and probably trained her as a manuscript painter. She may have worked in her father's workshop before her marriage. Via Wikipedia

0 notes

Text

The Shrinking World of Robert Walser

obstructivefictions.substack.com · by Dustin Illingworth

As a young man, the Swiss writer Robert Walser wanted to be an actor. In 1895, having fled a bank apprenticeship, he followed his brother, Karl, to Stuttgart, moving into an attic room across from the Royal Court Theater. A humiliating appraisal at the hands of another actor laid bare his inadequacies. The encounter is depicted in several later stories. (“You possess not the faintest trace of theatrical talent,” one doyenne concludes. “Everything about you is hidden, veiled, buried, dry, and wooden.”) That this great literary dissimulator should lack dramatic ability is one of the many appealing paradoxes Walser inhabits. But however unfit for the stage, he never abandoned the actor’s sense of improvisation. Even then, while yet a teenager, he disclosed a willingness to transform. “There isn’t going to be any acting career,” he wrote to his sister, “but if God so wills it, I am going to become a great writer.” For Walser, the difference between the two professions was negligible. In the ensuing decades, his life and writing would become their own kind of thrilling performance.

Walser’s brilliant short fictions ally him with Erik Satie, Paul Klee, and the other gifted miniaturists of modernism. The Walserian mode is elusive, gentle, courteous, submissive, youthful, disarming, and genial. His unassuming protagonists—students, artists, servants, and children—are poets of inconspicuousness and locality. They are impish and somehow otherworldly, petit-bourgeois sprites saddled with classes and clerkships, making suspiciously cheerful meaning of their own disenchantment. But this innocence is one of twentieth-century literature’s most sophisticated acts of legerdemain. The smaller, the more picturesque, the more seemingly guileless the narrative form, the more tightly Walser coils his lacerating ambiguities. Infinitely light and impossibly dense, his short prose works are gorgeous confinements out of which some radiant and contradictory energy is forever threatening to escape.

Thanks for reading Obstructive Fictions! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

He has been embalmed in lurid rumor. Nothing has yet managed to displace the legend of the perambulating crank, a sexless, hard-drinking oddball who walked twenty miles a day, heard malicious voices, wrote from the shrinking world of the “pencil territory,” spent two decades in an asylum, and died while out walking on Christmas Day. (An iconic photograph, shot by the local constable, shows him lying in the snow. The footprints end some distance before the body, as if he had managed to float part way into eternity.) The cult of Walser is sustained by seductive illusion, a relationship cannily understood by the writer himself. “My vocation, my mission, consists mainly in making every effort to keep my audience believing I am truly simple,” he wrote in 1925. But the irresistible romance of his art brut bona fides has come to obscure the rigorousness of his anti-commercial craft.

Susan Bernofsky’s “Clairvoyant of the Small: The Life of Robert Walser,” the first English-language biography of Walser, looks to dispel the fantasy of the idling, half-mad naïf. (The title is taken from one of Walser’s many admirers, W.G. Sebald: “He is no Expressionist visionary prophesying the end of the world, but rather a clairvoyant of the small.”) Bernofsky, a professor and distinguished translator of German literature, situates Walser’s eccentricity, reticence, and melancholy within a life of exemplary literary discipline. He comes across, first and foremost, as a tireless worker: living by his pen, badgering editors for advances, and enduring terrible austerity for his art. Bernofsky’s welcome corrective is exhaustively researched, though necessarily fragmentary. Given the relative scarcity of surviving letters during certain periods, Walser’s semi-autobiographical fictions are marshalled to fill in the gaps. What emerges from the record is a tantalizing chiaroscuro: flashes of life and work offset by shadowy lacunae.

Walser was born on April 15, 1878, to middle class parents, in Biel, Switzerland. His father, Adolf, a descendent of pastors and intellectuals, ran a general store specializing in toys and costume jewelry. His mother, Elise, a more significant presence in Walser’s imagination, suffered from crippling bouts of depression and rage. There is something fabulous and cursed about the eight Walser children. They are like figures from a fairy tale or play, mythic and prone to dazzling or tragic circumstance. The eldest brother died at fifteen; another preceded Robert into the Waldau asylum; another committed suicide; another, Robert’s best friend, Karl, was a celebrated illustrator, lothario, and stage designer for Max Reinhardt. His sister, Lisa, on whom he came to increasingly depend later in life, became a teacher in a mountain village. As the second youngest, Robert early on developed a keen understanding of the hierarchies that would animate his mature work. His acts of brotherly renunciation were in reality sly consolidations of power. This deceptive submissiveness can be found in many of his protagonists, who well understood what Bernofsky calls “the hidden power of the subservient.”

He left school at fourteen to apprentice as a bank clerk. The commis or bookkeeper, that modern, ink-stained figure of comic paradox that so intrigued Gogol, Melville, and Kafka, would become a fixture of his later fictions. After his dramatic failure in Stuttgart, he moved to Zurich in 1896, where he would live for almost a decade in a series of furnished rooms. His proto-Expressionist poetry first brought him to the attention of the public, though it would be his 1899 prose debut, the sinuous feuilleton “Lake Greifen,” that suggested the writing he would become known for.

The short prose piece is Walser’s essential narrative unit. His is a world of fables, travelogues, essays, idylls, meandering critical pieces on painting and theater, fantasies, dramolettes, and uncanny extemporizations. Their snow globe titles (“Little Snow Landscape,” “Two Little Fairy Tales,” “The Carousel”) and bejeweled surfaces belie the totalizing irony that awaits the reader. Subjects are effaced by way of endless refinement and qualification. Insignificance is embroidered with impossible verbal finery. Themes disintegrate, only to reform later with strange, totemic significance. The velocity and mutability of his observations are finally comic. Walser casts himself as a sort of alpine Buster Keaton, his slapstick energy palpable even as the set crumbles around him. He often relies on some pleasing foundational misdirection, as in “Vacation,” which begins: “The waves splash in the bay. Surely I’m lying when I claim this, but we do say anything to get something going.”

But there is an unplaceable torment in Walser. He is capable of abrupt, disfiguring bitterness, often delivered in deadpan volte. “The Factory Worker,” an otherwise gentle and lilting bit of nested fiction, terminates in sudden catastrophe, the onset of war worthy of no more than a caustic shrug: “who knows, perhaps the worker was amongst those who fell for the Fatherland.” These shelves of ice in the meadows of Walser’s world obstruct its traversal. For all of the postcard quaintness of his pastoral fantasies, they have about them a whiff of the demonic. Their frivolity disguises some permanent dislocation. To be compelled to make light of one’s desolation and absurdity is a punishment worthy of the damned. In these comedies of spiritual incomprehensibility, the laughter is never very far from a terrifying, runaway hysteria.

After the publication of his first novel, 1904’s “Fritz Kocher’s Essays,” a collection of short pieces masquerading as a precocious child’s notebook, Walser felt ready to take on Berlin. There he moved in with his brother Karl, whose artistic success granted Robert access to the city’s rich vein of Secessionist bohemian life. As in his sometimes whimsical fictions, Walser was not above acting the fool for his cosmopolitan friends. It was a version of himself he seemed to enjoy, the handsome yokel and rabble rouser, drinking heavily, flirting, eating too much at dinner parties, and insulting other writers. (He and Karl once chased the playwright Frank Wedekind into a café with shouts of “Muttonhead!” Wedekind never spoke to them again.) He enrolled in butler school to shock Karl’s wealthy patrons and spent an autumn in the employ of a Silesian count.

The European novel was then in the midst of its great internal emigration. Works like Robert Musil’s “The Confusions of Young Törless” and Rainer Maria Rilke’s “The Notebooks of Malte Laurids Brigge” featured young, disoriented protagonists exploring perilous inner worlds. Elsewhere, in Prague, Kafka was just beginning to document his dreamlike inner life. Walser’s free-floating fictions, pocket soliloquys suggesting an impenetrable private terrain, placed him at the forefront of this imaginative vanguard. Though his triptych of Berlin novels began in realist territory—“The Tanners,” published in 1907, nakedly dramatized the lives of the Walser brood; “The Assistant,” appearing a year later, was based on his apprenticeship to an inventor in Wädenswil—a great shift occurred with 1909’s “Jakob von Gunten.” With it the modernist novel plunged into bottomless ambiguity.

Walser’s favorite among his longer works, “Jakob von Gunten” purports to be the diary of a young man enrolled in a school for servants. The eponymous hero has run away from his aristocratic family, intent on becoming “a charming utterly spherical zero.” At the Benjamina Institute, he discovers a curious pedagogical limbo. Its teachers “are asleep, or they are dead, or seemingly dead, or they are fossilized, no matter, in any case we get nothing from them.” There is only one class: “How should a boy behave?” The entire operation is run by a mysterious brother and sister whose private chambers delineate a remote world every bit as tantalizing and fantastical as Kafka’s “The Castle.” The novel proceeds with a shimmering, oneiric quality. Jakob, a figure of indolence and mock-solemnity, thrives in this unfixed environment. He slowly gains ascendancy over the Benjamentas, humiliating and exalting them in equal measure. His motives for doing so remain inscrutable. Akin to an allegory sprung free of its meaning, the novel finally rejects both aspiration and submission alike. “How fortunate I am,” Jakob writes, “not to be able to see in myself anything worth respecting and watching! To be small and to stay small.” As the meticulous labor of his writing demanded an ever more circumscribed way of life, this mantra of diminution could have been Walser’s own

For all their sophistication, these remarkable novels made no discernible difference to Walser’s material condition. Broke and homesick, he returned to Switzerland in 1913, spending the next seven years in the attic of a temperance hotel in Biel. Though ambivalent about the war, he was called up several times—mainly to dig trenches and build fortifications—while maintaining an intimate correspondence with a laundress. (“Writing each other letters is like gently, carefully touching,” he wrote.) His prolific run of short fiction during this middle period is marked by its stylistic turn toward recursiveness. In stories like “The Sausage,” “Basta,” and “Well Then,” the spiraling repetitions of postwar formalists like Thomas Bernhard can be discerned. Despite this ambitious evolution, his audience and income diminished. Two novels, “Tobold” and “Theodor,” were lost or abandoned. A third, “The Robber,” an extravagant and sexually anxious work of deferment, would not be published until 1972. These abdications have about them a sense of willed reprieve. To write such works only to render them unavailable is an eminently Walserian gesture. His exploding ambition conspired with his shrinking life to produce a secret, vanishing literature. This was one way to free himself from fear of failure and the commercial grind: to consign particular works to oblivion. He would later write to Max Brod, in 1927, “Every book that has been printed is, after all, a grave for its author, isn’t it?”

After experiencing psychosomatic hand cramps, he developed a new form of composition commensurate with his narrowing circumstances. This abbreviated script, one to two millimeters in height, was written in the medieval German he preferred. Long considered to be indecipherable, or else a kind of private code, an entire story could fit on a business card or rejection slip. (He wrote on any surface available to him.) The secretive and provisional nature of his micrography—what he called the “pencil method”—ensured a private world of experimentation could exist outside the pressures of publishing. Combining necessary thrift with a need for seclusion, this miniaturization was, as Bernofsky has it, “an instinctual gesture of self-preservation.” It was also a rehearsal for a more permanent form of disappearance. The great silence of Herisau awaited, though not before the final flourishing of his mature style and its lush, fractal complexity.

Walser’s prose of this period—1925 to 1929���constitutes a new and remarkably baroque vision. It was as if, freed at last of his increasingly tenuous connection to the nineteenth-century realists that inspired him, he was free to become the avant-garde maximalist he knew himself to be all along. Neologisms, compounds, and abstract nouns proliferate helplessly, as in “The Robber,” whose many florid coinages includes the charming “littledaughterlinesses.” Layered puns introduce uncertainty to even the simplest of actions. Walser’s sentences, too, explode with arabesque complication. Sub-clauses intervene or obstruct rather than clarify, inviting sleek threads of digression. The slalom-like momentum of each sentence provides the drama usually offered by character or action. These techniques turn signification itself into a shape-shifting game. The primacy of artifice becomes Walser’s grand, late subject, a fitting capstone for modernism’s most unfathomable ironist.

In 1929, Lisa Walser, on the advice of a trusted doctor, brought her brother to the Waldau asylum. Fearful and hearing voices, he had recently made marriage proposals to both his landlords before asking them to stab him to death. His admission form listed him as schizophrenic, though the facts of his illness render this diagnosis unpersuasive. (Depression or bipolar disorder seems more likely.) A compliant if aloof patient, he spent his time working in the garden, shooting billiards, and writing poetry. There is a sense of him playing the invalid, as he had played the butler, his submission to routine a relief after the long unraveling in Biel. This equilibrium collapsed when Waldau’s new director deemed him well enough to reenter the world. Walser refused, and was forcibly transferred to Herisau’s Cantonal Asylum in 1933. What we know of Walser during these years comes from Carl Seelig, a critic and editor who befriended him and later became his legal guardian. (His book, “Walks with Walser,” recorded their conversations on art and life.) It was to Seelig that Walser supposedly delivered his infamous, puckish assertion: “I am not here to write, but to be mad.”

That this pithy, atmospheric, and oft-quoted line should be apocryphal—and it assuredly is—suggests the troublesome stickiness of the Walser mystique. The romantic image of the outsider artist going mad amid his tiny scraps of paper leaves no room for the reality of the ascetic craftsman. Bernofsky’s book extends the grace of adjusted proportion to its subject. It moves Walser’s oddity and muscular ambition into cohabitation. A gifted and longstanding translator of his work, her critical unpacking of Walser’s novels and stories is itself an act of oblique narrative. Rather than shed light on the tortuous life, his fiction’s proximity to autobiography somehow obscures it. He is forever backlit, a striding silhouette. “No man is entitled to act toward me as if he knew me,” one of his child-avatars says. Bernofsky would never presume to. By book’s end, Walser’s resistance becomes an unlikely dimension of intimacy. He eludes in the manner of those we feel we know best and end up misunderstanding completely.

After arriving at Herisau, Walser never published again. What writing he may have accomplished while institutionalized remains shrouded in mystery. According to two staff members, he would often write after meals while standing at a window ledge, hiding his work if anyone drew near. When he died, his coat pockets were found to be filled with letters and pay stubs—future palimpsests, perhaps, for the “torn-apart book of myself” he’d been writing since that failed audition in Stuttgart.

Thanks for reading Obstructive Fictions! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.obstructivefictions.substack.com · by Dustin Illingworth

1 note

·

View note

Text

On this day in Wikipedia: Saturday, 18th November

Welcome, 안녕하세요, Willkommen, Dzień dobry 🤗

What does @Wikipedia say about 18th November through the years 🏛️📜🗓️?

18th November 2022 🗓️ : Death - Tabassum

Tabassum, Indian actress and talk show host (b. 1944)

"Tabassum (born Kiran Bala Sachdev (later Govil); 9 July 1944 – 18 November 2022), was an Indian actress, talk show host and YouTuber, who started her career as child actor Baby Tabassum in 1947. She later had a television career as the host of first TV talk show of Indian television, Phool Khile..."

Image licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0? by Vijay govil

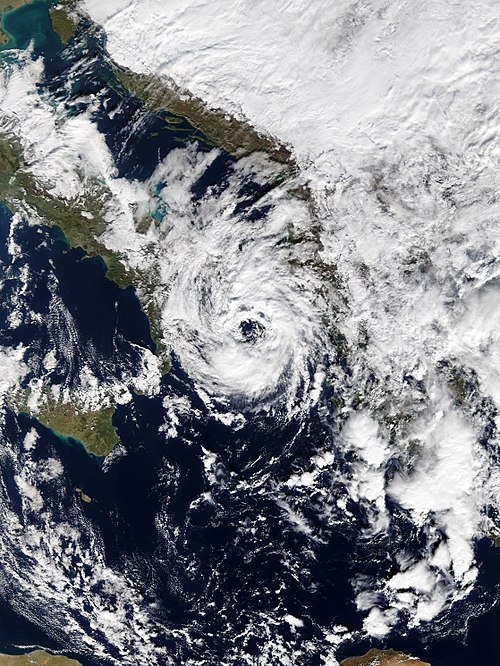

18th November 2017 🗓️ : Event - Cyclone Numa

Cyclone Numa, a rare "medicane", made landfall in Greece to become the worst weather event that the country had experienced since 1977.

"Cyclone Numa, also known as Medicane Numa, was a Mediterranean tropical-like cyclone with the properties of a subtropical cyclone. Numa formed on 11 November 2017 west of the British Isles, out of the extratropical remnants of Tropical Storm Rina, the seventeenth named storm of the 2017 Atlantic..."

Image by MODIS image captured by NASA’s Terra satellite

18th November 2013 🗓️ : Event - NASA

NASA launches the MAVEN probe to Mars.

"The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA ) is an independent agency of the U.S. federal government responsible for the civil space program, aeronautics research, and space research. Established in 1958, NASA succeeded the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA) to give the..."

Image by National Aeronautics and Space Administration

18th November 1973 🗓️ : Birth - Nic Pothas

Nic Pothas, South African cricketer and coach

"Nic Pothas (born 18 November 1973) is a South African cricket coach and former cricketer who played as a right-handed batsman and fielded as a wicket-keeper. In a total of over 200 first-class matches, he has taken over 500 catches. Pothas is an accomplished batsman, with an average of over 40 in..."

Image licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0? by AssociateAffiliate

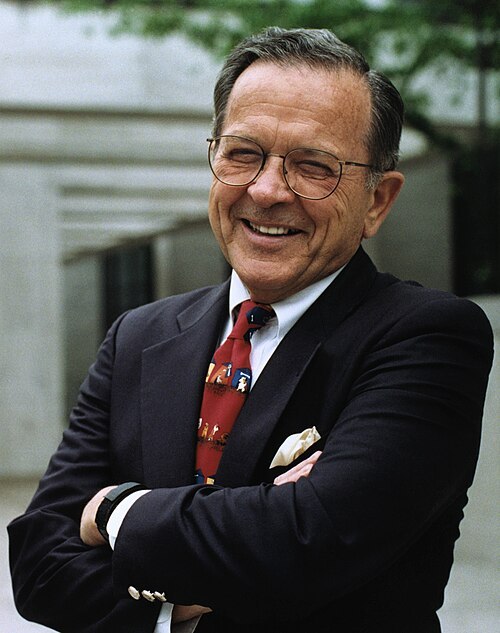

18th November 1923 🗓️ : Birth - Ted Stevens

Ted Stevens, American politician (d. 2010)

"Theodore Fulton Stevens Sr. (November 18, 1923 – August 9, 2010) was an American politician and lawyer who served as a U.S. Senator from Alaska from 1968 to 2009. He was the longest-serving Republican Senator in history at the time he left office. Stevens was the president pro tempore of the United..."

Image by United States Senate Historical Office

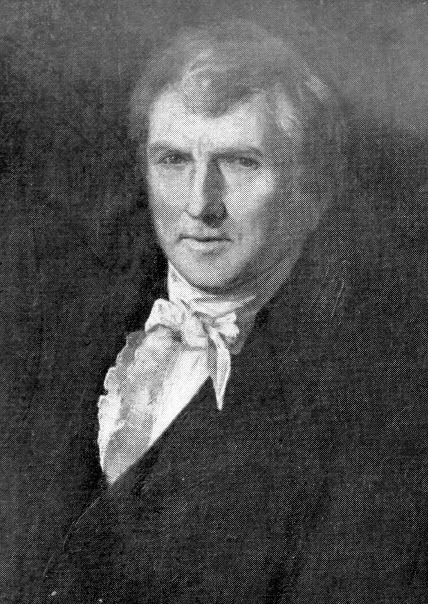

18th November 1814 🗓️ : Death - William Jessop

William Jessop, English engineer (b. 1745)

"William Jessop (23 January 1745 – 18 November 1814) was an English civil engineer, best known for his work on canals, harbours and early railways in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. ..."

Image licensed under CC-BY-SA-4.0? by

RobHist.46

18th November 🗓️ : Holiday - Christian feast day: Alphaeus and Zacchaeus

"Saints Alphaeus and Zaccheus were two Christians who were put to death in Caesarea, Palestine, in 303 or 304, according to church historian Eusebius in his Martyrs of Palestine. They are commemorated on November 18...."

Image by

Unknown Miniaturist, Italian (active first half of the 14th century)

0 notes

Text

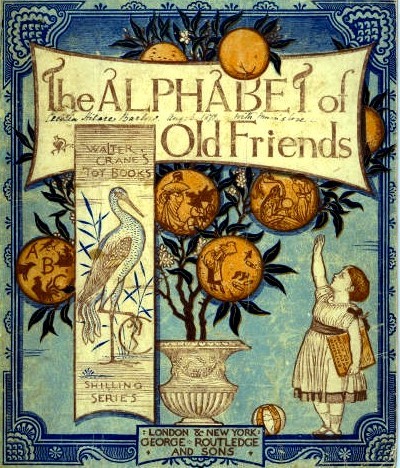

Sunday Evening Art Gallery -- Walter Crane

Walter Crane (1845-1915) was an English illustrator, painter, and designer primarily known for his imaginative illustrations of children’s books.

The son of the portrait painter and miniaturist Thomas Crane (1808–59), Crane is considered to be among the most influential and most prolific children’s book creators of his generation.Crane’s work featured some of the more colorful and detailed…

View On WordPress

1 note

·

View note

Text

Anya Taylor-Joy Net Worth - Celebrity Net Worth

Anya Taylor-Joy Net Worth – Celebrity Net Worth

Anya Taylor-Joy is an American/English/Argentine actress who has a net worth of $7 million. Anya Taylor-Joy first gained widespread recognition for her leading role in the 2015 folk-horror film “The Witch.” Following this, she starred in such films as “Split,” “Glass,” “Thoroughbreds,” and “Emma.” On television, Taylor-Joy starred in the British series “The Miniaturist” and “Peaky Blinders,” and…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Photo

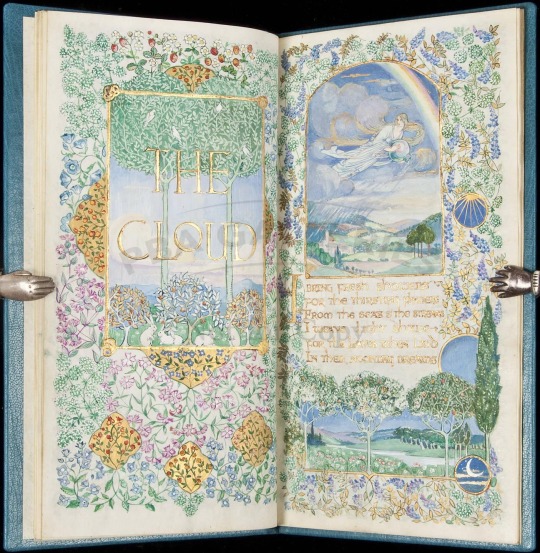

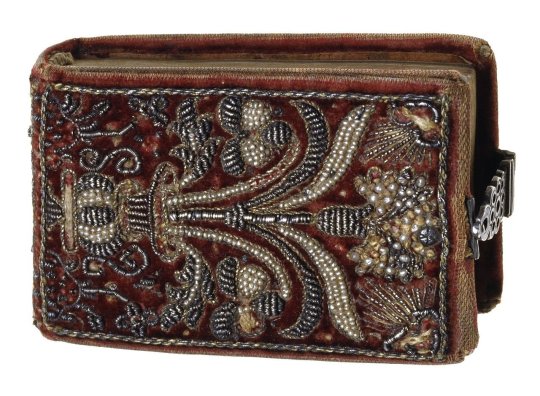

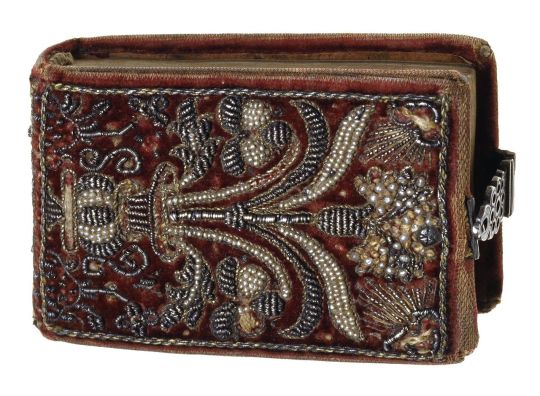

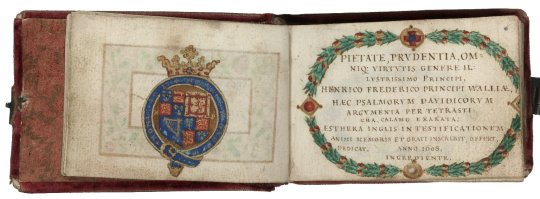

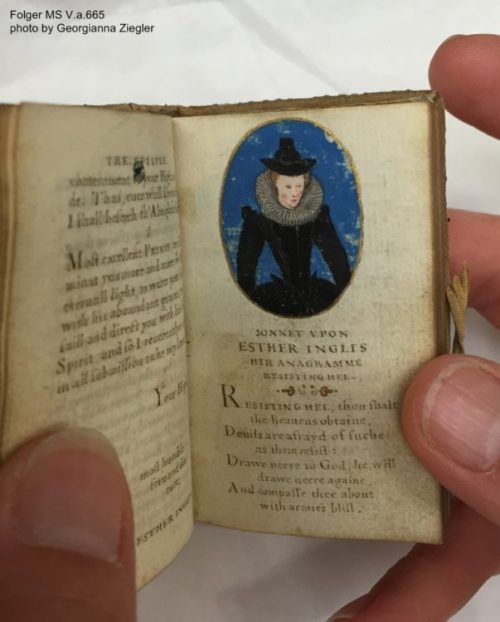

August 10th 1624 saw the death of Esther Inglis, calligrapher and miniaturist.

Esther Inglis, daughter of a French immigrant, was a celebrated calligrapher. She produced exquisitely illuminated documents and little books, illustrated with flowers. Her parents, Nicolas Langlois and Marie Presot, were French Huguenots who took refuge in England in about 1569, later settling in Edinburgh. Their daughter Esther seems always to have used the surname ‘Inglis’, the Scottish form of Langlois.

In 1596, Esther married Bartholomew Kello, and by 1604 had moved with him to London. They had six children, of whom four lived to adulthood. Kello, a clergyman, had a church in Essex between 1607 and 1614. In 1615 the family returned to Edinburgh.

Esther went on to become an exceptionally skilled calligrapher (calligraphy is the design and execution of decorative handwriting), illustrator and embroiderer. Her manuscripts vary from religious texts and psalms to secular (non-religious) works - which Inglis transcribed - to designs for emblems (symbolic pictures) and heraldic arms.

She often dedicated her manuscripts to members of the Elizabethan and Jacobean court, and high-ranking European protestants. Often presented as gifts in diplomatic exchange, it is believed that Inglis's early works may have been used to support the negotiations leading up to James VI’s accession to the English throne.Inglis was multilingual and wrote in Latin, Scots and French. From 1599 her manuscripts, which are miniature in scale, also include tiny self-portraits which promoted her authorship and talent. These images are the earliest known self-portraits by a female artist working in Britain.

Her intricate illustrations often feature animals, flowers and fruit, and Inglis may have used emblem books (books of symbolic pictures often accompanied by mottoes, morals or poems) as a source of inspiration for her designs. Inglis was multitalented and she also embroidered her bound manuscripts, using precious metal threads and seed pearls (tiny natural pearls less than 2mm in size) on velvet. Her works transcend the traditional boundaries of text, visual and textile art forms, and as such she occupies a unique place in European and Scottish renaissance culture.

Despite her talent and prestigious clients, by her death Inglis had accrued significant debts. She died in Leith in August 1624, the dates differ a wee bit.

Today around sixty of her surviving works are recorded in public and private collections across the world. Some of the most decorative and accomplished works can be found in the National Library of Scotland, the Royal Collection Trust and the Folger Shakespeare Library in Washington, D.C.

The portrait of Esther Inglis can be seen at the Scottish National Portrait Gallery as part of our Reformation to Revolution display.

The University of St Andrews purchased some of her work over ten years ago, you can learn more about her and view some of the pics at the link below.

https://special-collections.wp.st-andrews.ac.uk/2011/07/25/highlight-esther-ingliss-octonaires-a-masterpiece-in-miniature/

20 notes

·

View notes