#cw racism against latinx

Text

Some people think the word "gringo" is a slur. It literally means something like "foreigner", someone that comes from another country. But I just realized that when a Brazilian says "gringo!!!!" like they are genuinely happy to see you it's really because they are glad you're here and they want to teach you stuff about Brazil and integrate you to the culture and learn about yours and make friends with you, we are just really extroverted and we love other cultures.

Like, last week I was at a Buddhist temple that had all types of Asian culture related things (even though Buddhism isn't prevalent in every country in Asia, here you will get white christians praying on the temple because historically we incorporated so many religions into our own culture and people think "well, what if it works?" and sensible people don't think it's heretical). It was a also a celebration that incorporated a Brazilian festival called "June parties", that became so popular that they start in the end of May and go until August instead of actually lasting for only June and it was based on catholic beliefs but people from all religions go just to have fun, dance and eat. And then we were doing that, but adding multiple Asian cultures in a Buddhist temple. All at the same time, same place, everybody having fun.

Anyway some gringos were there and they were a bit overwhelmed but really happy to see all the different cultural things going on, when to us it is just another year's festival and sometimes we forget this doesn't happen everywhere. And people were trying to explain to them why we do that, what you can do at those festivals and they were sunburned and everyone just wanted to integrate them to the festival. English was not even their first language and everyone was struggling a bit to communicate but we tried because it's so fun when someone is genuinely interested in the mix up culture/faith/ethnicities we have here.

In some rare occasions, if people say "gringo." and it sounds too serious and they say it with a bit of a condescending tone, you just did something racist or disrespectful and then it becomes something that means "this person thinks they are so superior and they haven't even tried to get to know us", kind of like when people say in English "this is white people stuff" right after they said something racist that shows lack of awareness and privilege. That's what I think might come closest to an English expression in that context.

If you get offended by someone's "very excited that you're here" tone of saying "gringo!!!" then you might get offended by the monotone "gringo." which basically means that you were going racist/xenophobic. Most people will try the "welcome" tone of the word, and they might give you "gringo" as a nickname and it usually means that you are well-liked. Just make sure you are the type of person that will continue to get that happy emphasis on the word and don't say racist shit.

Tldr: it's not a slur and people are usually genuinely interested in you and trying to integrate you into the culture and happy to see that you wanted to come here in the first place. But if anyone is openly racist, and people get irritated, then the very monotone way of calling someone a gringo serves as a warning to other Brazilians that you were saying racist things without even trying to get to know the culture or the people in it. The word exists in both Portuguese and Spanish but I am talking about Brazilian Portuguese since that's where I'm from. It's all in the tone and it's never a slur, and in its negative meaning it just serves to tell other Brazilians that you are saying racist stuff, but it usually has a sort of "hey, it's cool that you're here and I wanna show you some nice stuff to do around here".

#on the word gringo#Brazilian culture#it's all in the tone#and it is not a slur#it has more than one meaning#cw racism against latinx#cw religion mention

185 notes

·

View notes

Text

Revised Textual Analysis Blog Post

In the CW’s Roswell, New Mexico, Liz Ortecho is a brilliant biomedical science researcher. She is a vital asset throughout season 1 and 2 due to her extensive scientific and medical knowledge and impressive research background. As a pre-medicine student, it inspired me to see a young woman, especially a young Latina woman, being represented as a reputable and respected scientist. After further research and reflection, Roswell’s representation of women in medicine is extremely well done and provides a character that young girls can look up to in a world where women in medicine are underestimated and discriminated against.

One of the most emphasized aspects of Liz’s identity is her career as a biomedical researcher. With her abilities, she is able to develop a serum using Max’s cells that slowly degrades alien cells and shuts down their powers, as well as the antidote that reverses the damage of this poison. She never once shies away from using her intelligence, and eventually is able to bring Max back to life in season 2. As she is working tirelessly in the lab to prepare an alien heart strong enough to give to Max, she talks to Rosa and says:

“I chose regenerative medicine as my focus when you died. ‘Cause I was broken, and I wanted to repair the irreparable. It’s an ethics nightmare. I have been spit on by protesters and shut down by the government. I’ve worked on tiny rat hearts my whole life, waiting until someone in power would believe that I could do this with people, too. And over and over, old men on boards have told me to stay in my lane. To calm down. To wait. But I can do this!” (Stay (I Missed you)).

This quote encapsulates everything the Roswell writers were pushing against when they established Liz as a female scientist lead who was a force to be reckoned with. It touches on the discrimination that women and LatinX community in STEM careers face. It was imperative that Liz discloses the discrimination she’s faced in order to add realism to this situation. Although I argue that creating more female STEM leads in TV shows is exactly the kind of representation needed to push back against outdated stereotypes of scientists, it’s important to address the issues that still occur today.

This is so important because the reality is, while women in STEM have made significant progress, there is still much more work to be done to establish further equality in this field. In fact, according to a peer-reviewed article published in Frontiers in Psychology, “A study based on data from a Swedish funding agency reported that women need to author twice as many publications to obtain the same scientific competence score as men (Wenneras and Wold, 1997)” (“Facing Racism and Sexism in Science by Fighting Against Social and Implicit Bias: A Latina and Black Woman’s persective”). This exact issue is what Liz touches on in Roswell, New Mexico, proving that this is a real and ongoing issue. Implicit gender and racial bias are persistent and can greatly damage the careers of women in science. Providing a character like Liz who was able to overcome these obstacles and establish herself as a respected researcher who was able to obtain a research grant by the end of season one is taking great strides in the right direction. Young girls and members of the LatinX community can tune into the show and become inspired by her confidence, intelligence, and leadership.

It is clear that Roswell, New Mexico prioritized the representation of a wide range of minority groups that do not get frequent or accurate representation like the LGBTQ+, Latinx, immigrants, African American, Native American mentally ill, and disabled communities, to name a few. While it could be debated how well they provide accurate representation of each one, I argue that they succeeded in shedding light on the intelligence and ambition of women and Latinx women in science. At first, I criticized the show for only showing an unrealistic portrayal of how successful Liz was and not addressing the significant discrimination that women and Latinx people still face today. However, as the show progressed, the showrunners portrayed Liz in a nuanced way by addressing the adversity she faced like being consistently underestimated and not having any role models to look up to while also showing how she was still able to be successful. My only critique is that they shouldn’t have waited until season 2 to address these issues. However, overall, the show provides one of the only TV show characters that aspiring Latina women in STEM can look up to for inspiration.

0 notes

Text

Pointless star wars wanking beneath the cut. cw slavery

It’s really frustrating that star wars AS A WHOLE is a series that regularly uses and coopts the concept of slavery and being a slave to move the plot forward without every actually addressing the damage slavery causes in an enslaved person.

We’ve now had two trilogies where the main character(s) were enslaved persons.

Anakin was owned but was freed and then “chose” (though, I don’t honestly know how much choice can be assigned to a 9 year old chosing between being cast aside and staying with the one person he knows outside his mom) to join a ascetic order with a master, no right to own property beyond his clothing and weapon, and not allowed to form meaningful emotional connections with anyone.

Rey was sold to a junkyard dealer who had no interest in even keeping her alive beyond what was necessary to keep her working. Her plantation was destroyed and she escaped in the mess.

Finn was enslaved as a baby, raised in a militaristic organization with no concept of life outside of it, and when given his first orders to fire and kill civilians chose not to, and took the first opportunity presented to him to run.

(If we are accepting Solo as a part of canon then Han was also essentially enslaved as part of that child gang before he used the imperial military to escape, and the girl in that movie also continued to be enslaved)

You have three distinct versions of the “runaway/freed slave” narrative and absolutely none of the follow through for any of them

Anakin’s railing against the Jedi Order is always framed as Sidious intervention, not the fact that he must have recognized as he got older that he had gained nothing in being freed. His life was not his own, he just got to live it on a grander scale then he would have on Tattooine. His and Padme’s relationship was in secret, the same it would have had to be if he had fallen in love with another slave. He literally just moves from master to master without a moment of freedom his entire life until he kills Palps in ROTJ.

Rey and Finn could have been such interesting foils in dealing with past enslavement, with Rey obsessed with her “past” and Finn’s completely disinterest in examining his (which, I feel was a terrible path to take with his character in canon, and fanon works that do examine how he might deal with suddenly realising he has a past he could be curious about are delightful.) The two ways enslaved people move beyond their enslavement.

And then to just toss Jannah and the runaway stormtroopers into EpIX as a tossaway is just frustrating. Especially because they were all POC, it felt very much like they were referencing the Great Dismal Swamp maroons, but I know they weren’t (I doubt JJ knows who they are). It could have been such a powerful narrative for the “spy” in the First Order to actually be a network of stormtroopers who were all running away and sending any info they had to the resistance. But no, we had to have Hux throw a hissy fit.

I don’t think I have anywhere I am going with this, I just find it frustrating how this is such an integral part of what star wars is and yet there’s no acknowledgement of it by the majority of the creatives involved and I think that is why I am so consistently disappointed with canon work that has come after the OT. Fanon tends to be much more aware of this thread and there’s quite a few authors who’ve done it justice.

(also, DON’T THINNK I DIDN’T NOTICE that JJ made the LATINO MAN a SPICE RUNNER for comedic effect. I just, jesus. I just fucking hate that so much. If you want a great fic about spacelatinx racism can I recommend: Home Out in the Wind by bomberqueen17, https://archiveofourown.org/series/468505 space latinos dealing with racist stereotypes is dealt with incredibly well, as well as the disapora of latinx peoples including those of Alderaan)

137 notes

·

View notes

Text

News and important updates on POS System Equipment & POS.

Scenes from The Searchers (1956), starring John Wayne and set during the Texas-Indian Wars. The film is considered one of the most influential Westerns ever made.

“It just so happens we be Texicans,” says Mrs. Jorgensen, an older woman wearing her blond hair in a tight bun, to rough-and-tumble cowboy Ethan Edwards in the 1956 film The Searchers. Mrs. Jorgensen, played by Olive Carey, and Edwards, played by John Wayne, sit on a porch facing the settling dusk sky, alone in a landscape that is empty as far as the eye can see: a sweeping desert vista painted with bright orange Technicolor. Set in 1868, the film lays out a particular telling of Texas history, one in which the land isn’t a fine or good place yet. But, with the help of white settlers willing to sacrifice everything, it’s a place where civilization will take root. Nearly 90 years after the events depicted in the film, audiences would come to theaters and celebrate those sacrifices.

“A Texican is nothing but a human man way out on a limb, this year and next. Maybe for 100 more. But I don’t think it’ll be forever,” Mrs. Jorgensen goes on. “Someday this country’s going to be a fine, good place to be. Maybe it needs our bones in the ground before that time can come.”

There’s a subtext in these lines that destabilizes the Western’s moral center, a politeness deployed by Jorgensen that keeps her from naming what the main characters in the film see as their real enemies: Indians.

In the film, the Comanche chief, Scar, has killed the Jorgensens’ son and Edwards’ family, and abducted his niece. Edwards and the rest of Company A of the Texas Rangers must find her. Their quest takes them across the most treacherous stretches of desert, a visually rich landscape that’s both glorious in its beauty and perilous given the presence of Comanche and other Indigenous people. In the world of the Western, brutality is banal, the dramatic landscape a backdrop for danger where innocent pioneers forge a civilization in the heart of darkness.

The themes of the Western are embodied by figures like Edwards: As a Texas Ranger, he represents the heroism of no-holds-barred policing that justifies conquest and colonization. While the real Texas Rangers’ history of extreme violence against communities of color is well-documented, in the film version, these frontier figures, like the Texas Rangers in The Searchers or in the long-running television show The Lone Ranger, have always been portrayed as sympathetic characters. Edwards is a cowboy with both a libertarian, “frontier justice” vigilante ethic and a badge that puts the law on his side, and stories in the Western are understood to be about the arc of justice: where the handsome, idealized male protagonist sets things right in a lawless, uncivilized land.

The Western has long been built on myths that both obscure and promote a history of racism, imperialism, toxic masculinity, and violent colonialism. For Westerns set in Texas, histories of slavery and dispossession are even more deeply buried. Yet the genre endures. Through period dramas and contemporary neo-Westerns, Hollywood continues to churn out films about the West. Even with contemporary pressures, the Western refuses to transform from a medium tied to profoundly conservative, nation-building narratives to one that’s truly capable of centering those long victimized and villainized: Indigenous, Latinx, Black, and women characters. Rooted in a country of contested visions, and a deep-seated tradition of denial, no film genre remains as quintessentially American, and Texan, as the Western, and none is quite so difficult to change.

*

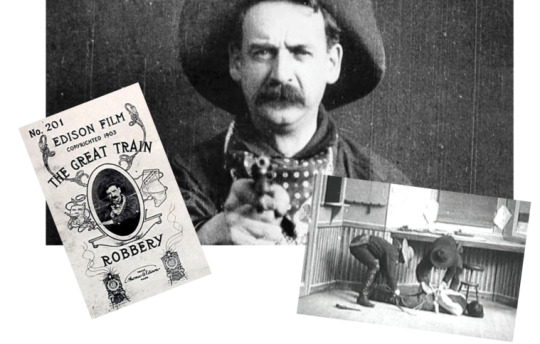

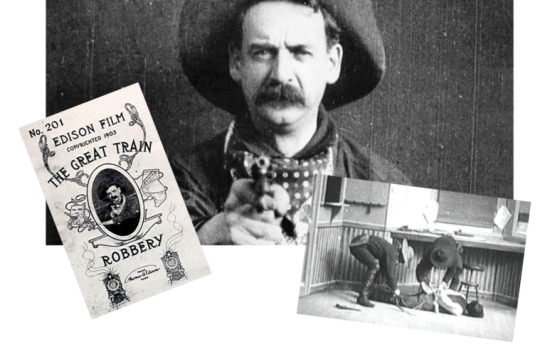

With origins in the dime and pulp novels of the late 19th century, the Western first took to the big screen in the silent film era. The Great Train Robbery, a 1903 short, was perhaps the genre’s first celluloid hit, but 1939’s Stagecoach, starring Wayne, ushered in a new era of critical attention, as well as huge commercial success. Chronicling the perilous journey of a group of strangers riding together through dangerous Apache territory in a horse-drawn carriage, Stagecoach is widely considered to be one of the greatest and most influential Westerns of all time. It propelled Wayne to stardom.

During the genre’s golden age of the 1950s, more Westerns were produced than films of any other genre. Later in the 1960s, the heroic cowboy character—like Edwards in The Searchers—grew more complex and morally ambiguous. Known as “revisionist Westerns,” the films of this era looked back at cinematic and character traditions with a more critical eye. For example, director Sam Peckinpah, known for The Wild Bunch (1969), interrogated corruption and violence in society, while subgenres like spaghetti Westerns, named because most were directed by Italians, eschewed classic conventions by playing up the dramatics through extra gunfighting and new musical styles and creating narratives outside of the historical context. Think Clint Eastwood’s The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly (1966).

The Great Train Robbery (1903), a short silent film, was perhaps the first iconic Western.

In the wake of the anti-war movement and the return of the last U.S. combat forces from Vietnam in 1973, Westerns began to decline, replaced by sci-fi action films like Star Wars (1977). But in the 1990s, they saw a bit of rebirth, with Kevin Costner’s revisionist Western epic Dances With Wolves (1990) and Eastwood’s Unforgiven (1992) winning Best Picture at the Academy Awards. And today, directors like the Coen brothers (No Country for Old Men, True Grit) and Taylor Sheridan (Hell or High Water, Wind River, Sicario) are keeping the genre alive with neo-Westerns set in modern times.

Still, the Old West looms large, says cultural critic and historian Richard Slotkin. Today’s Western filmmakers know they are part of a tradition and take the task seriously, even the irreverent ones like Quentin Tarantino. Tarantino called Django Unchained (2012) a spaghetti Western and, at the same time, “a Southern.” Tarantino knows that the genre, like much of American film, is about violence, and specifically racialized violence: The film, set in Texas, Tennessee, and Mississippi, flips the script by putting the gun in the hand of a freed slave.

Slotkin has written a series of books that examine the myth of the frontier and says that stories set there are drawn from history, which gives them the authority of being history. “A myth is an imaginative way of playing with a problem and trying to figure out where you draw lines, and when it’s right to draw lines,” he says. But the way history is made into mythology is all about who’s telling the story.

Slotkin’s work purports that the logic of westward expansion is, when boiled down to its basic components, “regeneration through violence.” Put simply: Kill or die. The very premise of the settling of the West is genocide. Settler colonialism functions this way; the elimination of Native people is its foundation. It’s impossible to talk about the history of the American West and of Texas without talking about violent displacement and expropriation.

“The Western dug its own hole,” says Adam Piron, a film programmer at the Sundance Indigenous Institute and a member of the Kiowa and Mohawk tribes. In his view, the perspectives of Indigenous people will always be difficult to express through a form tied to the myth of the frontier. Indigenous filmmakers working in Hollywood who seek to dismantle these representations, Piron says, often end up “cleaning somebody else’s mess … And you spend a lot of time explaining yourself, justifying why you’re telling this story.”

While the Western presents a highly manufactured, racist, and imperialist version of U.S. history, in Texas, the myth of exceptionalism is particularly glorified, perpetuating the belief that Texas cowboys, settlers, and lawmen are more independent, macho, and free than anywhere else. Texas was an especially large slave state, yet African Americans almost never appear in Texas-based Westerns, a further denial of histories. In The Searchers, Edwards’ commitment to the white supremacist values of the South is even stronger than it is to the state of Texas, but we aren’t meant to linger on it. When asked to make an oath to the Texas Rangers, he replies: “I figure a man’s only good for one oath at a time. I took mine to the Confederate States of America.” The Civil War scarcely comes up again.

The Texas Ranger is a key figure in the universe of the Western, even if Ranger characters have fraught relationships to their jobs, and the Ranger’s proliferation as an icon serves the dominant Texas myth. More than 300 movies and television series have featured a Texas Ranger. Before Chuck Norris’ role in the TV series Walker, Texas Ranger (1993-2001), the most famous on-screen Ranger was the titular character of The Lone Ranger (1949-1957). Tonto, his Potawatomi sidekick, helps the Lone Ranger fight crime in early settled Texas.

Meanwhile, the Ranger’s job throughout Texas history has included acting as a slave catcher and executioner of Native Americans. The group’s reign of terror lasted well into the 20th century in Mexican American communities, with Rangers committing a number of lynchings and helping to dispossess Mexican landowners. Yet period dramas like The Highwaymen (2019), about the Texas Rangers who stopped Bonnie and Clyde, and this year’s ill-advised reboot of Walker, Texas Ranger on the CW continue to valorize the renowned law enforcement agency. There is no neo-Western that casts the Texas Ranger in a role that more closely resembles the organization’s true history: as a villain.

The Coen brothers’ No Country for Old Men (2007) ushered in the era of neo-Westerns set in modern times.

Ushered in by No Country for Old Men (2007), also set in Texas, the era of neo-Westerns has delivered films that take place in a modern, overdeveloped, contested West. Screenwriter Taylor Sheridan’s projects attempt to address racialized issues around land and violence, but they sometimes fall into the same traps as older, revisionist Westerns—the non-white characters he seeks to uplift remain on the films’ peripheries. In Wind River (2017), the case of a young Indigenous woman who is raped and murdered is solved valiantly by action star Jeremy Renner and a young, white FBI agent played by Elizabeth Olsen. Sheridan’s attempt to call attention to the epidemic of missing and murdered Indigenous women still renders Indigenous women almost entirely invisible behind the images of white saviors.

There are directors who are challenging the white male gaze of the West, such as Chloé Zhao, whose recent film Nomadland dominated the 2021 Academy Award nominations. In 2017, Zhao’s film The Rider centered on a Lakota cowboy, a work nested in a larger cultural movement in the late 2010s that highlighted the untold histories of Native cowboys, Black cowboys, and vaqueros, historically Mexican cowboys whose ranching practices are the foundation of the U.S. cowboy tradition. And Concrete Cowboy, directed by Ricky Staub and released on Netflix in April, depicts a Black urban horse riding club in Philadelphia. In taking back the mythology of the cowboy, a Texas centerpiece and symbol, perhaps a new subgenre of the Western is forming.

Despite new iterations, the Western has not been transformed. Still a profoundly patriotic genre, the Western is most often remembered for its classics, which helped fortify the historical narrative that regeneration through violence was necessary for the forging of a nation. In Texas, the claim made by Mrs. Jorgensen in The Searchers remains a deeply internalized one: The history of Texas is that of a land infused with danger, a land that required brave defenders, and a land whose future demanded death to prosper.

In Westerns set in the present day, it feels as if the Wild West has been settled but not tamed. Americans still haven’t learned how to live peacefully on the land, respect Indigenous people, or altogether break out of destructive patterns of domination. The genre isn’t where most people look for depictions of liberation and inclusion in Texas. Still, like Texas, the Western is a contested terrain with an unclear future. John Wayne’s old-fashioned values are just one way to be; the Western is just one way of telling our story.

This article was first provided on this site.

We hope you found the article above of help and/or of interest. Similar content can be found on our main site: southtxpointofsale.com

Please let me have your feedback below in the comments section.

Let us know what topics we should write about for you in the future.

youtube

#Point of Sale#harbortouch Lighthouse#harbortouch Pos#lightspeed Restaurant#point of sale#shopkeep Reviews#shopkeep Support#toast Point Of Sale#toast Pos Pricing#toast Pos Support#touchbistro Pos

0 notes

Text

(misgendering mention cw, anti-hispanic xenophobia cw, catcalling cw, transphobia cw, antiblack racism cw)

An important part of the idea that “your experiences don’t equal a larger pattern and #NotAllX’s” is that that means you don’t have to be afraid.

When a man catcalls you, that’s bad, but it’s not a plague on America. When you’re misgendered, it’s bad, but it’s not a sign that this space is not safe for you. They’re just... assholes.

This goes the other way as well. When the cashier at a McDonald’s speaks in accented English, that’s not part of some massive Mexican plot to take over America. It’s a cashier at McDonald’s speaking in accented English. And so on.

If there’s a lot of data showing up that is scientifically accurate and statistically well-done that shows large patterns, then yes, this is a major problem Everywhere. If you have lots of friends who have the same experiences as you, then that means it’s a problem for you and your friends, and it makes sense to unify. You can even detect patterns, sometimes, and maybe make up useful strategies for addressing it.

But you also have to then fund studies, if you want to be taken seriously at the governmental levels. And also studies are important in order to verify your hypotheses! There are reasons that studies are required- they’re not just a set of hoops to jump through.

This is where I was erring with that girl who hurt me, Aviella. I kept interpreting her behavior as somehow Representative of a Vast SJ Conspiracy when really, it was just some dumb high schooler being an asshole. And yeah, there are lots of dumb high schoolers being assholes, and yeah, it’s useful theoretically to look into how the terribleness is woven together. But also. Like. I don’t have data.

This is why #NotAllX’s is so incredibly important. If you start believing #YesAllX’s, then you’re fucked. Because all X’s are terrifying and scary and always hurting you- and now all X’s are acceptable targets. That’s the impetus behind Trump’s thing against Latinxs.

And that’s the impetus behind Aviella’s thing about whites. #YesAllWhites are racist. #YesAllPOC are the same and agree with her.

Or #YesAllMen are threatening, for some feminists, or #YesAllAmabs for some different feminists. We all know how these turn out: women feel more scared than ever, and this interacts badly with racism and transphobia.

I’m guilty of this too. #YesAllBlacks hate me, therefore I hate all blacks. #YesAllSJWs, therefore I’m surprised when some feminists are nice to me. #YesAllGoodPeople hate me because I’m despicable and privileged. #YesAllAntifas are terrible and threatening and will hurt others, and this rhetoric will destroy America and free speech!!! - All this despite the fact that I have no evidence one way or the other.

This kind of overemphasis on lived experiences is seriously detrimental to marginalized people’s mental health and reasoning capabilities. If I had to define it, I’d say it was of two parts: 1) catastrophizing life incidents and 2) generalizations about large groups of people. Neither are good habits to get into.

Lived experiences are trivially correct and important. Events in your own life are real and it is important for marginalized people to be able to compare their own experiences, especially when Science (TM) basically ignores them. However, abandoning actual science is foolhardy in the extreme, and leads to quaking in fear of windmills.

A lot of times in writing it’s useful to utilize events from your life to launch into a larger story. But it must never be forgotten that, ultimately, this incident was just one incident. The personal is political only in the sense that society affects the personal, not in the sense that the personal represents some kind of Definite Pattern.

You don’t have to be afraid of the full force of racism when some white girl arrives wearing dreadlocks. You (well, I) don’t have to be afraid of the full force of antifa wrath when Aviella talks about punching Nazis. Every time Aviella talks to me, the entire weight of her cruelty towards me doesn’t have to be connected. It’s another incident, a needle in a haystack, and it ultimately matters mostly as part of the haystack- it’s trivial in itself, and it is not necessarily painful.

However, it is important- but only as important as it is. Nonstructural oppression is important. And this is important. Just not with the importance of the entire structure behind it.

This is relevant to the kind of thing that @testblogdontupvote and @unknought were discussing in this post. Unknought appeared to be asking for some kind of example of sj attacking Objective Truth.

While this isn’t a direct denial of objective truth, overfocusing on lived experiences and extrapolating those lived experiences to whole nations is certainly a flaw of some sj narratives. Slam poetry is one particular avenue wherein lived experiences are magnified beyond their actual proven truth and extrapolated into somehow being about structural oppression - many times that I have seen, arguments are made based on citing a few statistics and writing a long personal experience. Along with the above-referenced #YesAllX’s campaign, a pop-culture sj misconception of the idea of privilege is that all privileged people do x while all marginalized people do y.

#there is more to be said about one apple than about all the apples in the world#sj#effortpost#privilege#writing#about her#rationality#in search of truth

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Textual Analysis Blog Post

In the CW’s Roswell, New Mexico, Liz Ortecho is a brilliant biomedical science researcher. She is a vital asset throughout season 1 and 2 due to her extensive scientific and medical knowledge and impressive research background. As a pre-medicine student, it inspired me to see a young woman, especially a young Latina woman, being represented as a reputable and respected scientist. After further research and reflection, Roswell’s representation of women in medicine is extremely well done and provides a character that young girls can look up to in a world where women in medicine are underestimated and discriminated against.

One of the most emphasized aspects of Liz’s identity is her career as a biomedical researcher. With her abilities, she is able to develop a serum using Max’s cells that slowly degrades alien cells and shuts down their powers, as well as the antidote that reverses the damage of this poison. She never once shies away from using her intelligence, and eventually is able to bring Max back to life in season 2. As she was working tirelessly in the lab to prepare an alien heart strong enough to give to Max, she talks to Rosa and says: “I chose regenerative medicine as my focus when you died. ‘Cause I was broken, and I wanted to repair the irreparable. It’s an ethics nightmare. I have been spit on by protesters and shut down by the government. I’ve worked on tiny rat hearts my whole life, waiting until someone in power would believe that I could do this with people, too. And over and over, old men on boards have told me to stay in my lane. To calm down. To wait. But I can do this!” (Stay (I Missed you)). This quote encapsulates everything the Roswell writers were pushing against when they established Liz as a female scientist lead who was a force to be reckoned with. It touches on the discrimination that women and LatinX community in STEM careers face. It was imperative that Liz discloses the discrimination she’s faced in order to add realism to this situation. Although I argue that creating more female STEM leads in TV shows is exactly the kind of representation needed to push back against outdated stereotypes of scientists, it’s important to address the issues that still occur today.

Because the reality is, while women in STEM have made significant progress, there is still much more work to be done to establish further equality in this field. In fact, according to a peer-reviewed article published in Frontiers in Psychology, “A study based on data from a Swedish funding agency reported that women need to author twice as many publications to obtain the same scientific competence score as men (Wenneras and Wold, 1997)” (“Facing Racism and Sexism in Science by Fighting Against Social and Implicit Bias: A Latina and Black Woman’s persective”). This exact issue is what Liz touched on in Roswell, New Mexico, proving that this is a real and ongoing issue. Implicit gender and racial bias are persistent and can greatly damage the careers of women in science. Providing a character like Liz who was able to overcome these obstacles and establish herself as a respected researcher who was able to obtain a research grant by the end of season one is taking great strides in the right direction. Young girls and members of the LatinX community can tune into the show and become inspired by her confidence, intelligence, and leadership. However, I would have liked to see more than just one offhanded quote from Liz talking about the discrimination she has faced all of her life. We cannot make greater steps towards equality if past issues are not called out and addressed. Despite this missing part, the show overall successively sheds light on the intelligence and ambition of women and Latinx women in science as a whole.

0 notes

Text

News and important updates on POS System Equipment & POS.

Scenes from The Searchers (1956), starring John Wayne and set during the Texas-Indian Wars. The film is considered one of the most influential Westerns ever made.

“It just so happens we be Texicans,” says Mrs. Jorgensen, an older woman wearing her blond hair in a tight bun, to rough-and-tumble cowboy Ethan Edwards in the 1956 film The Searchers. Mrs. Jorgensen, played by Olive Carey, and Edwards, played by John Wayne, sit on a porch facing the settling dusk sky, alone in a landscape that is empty as far as the eye can see: a sweeping desert vista painted with bright orange Technicolor. Set in 1868, the film lays out a particular telling of Texas history, one in which the land isn’t a fine or good place yet. But, with the help of white settlers willing to sacrifice everything, it’s a place where civilization will take root. Nearly 90 years after the events depicted in the film, audiences would come to theaters and celebrate those sacrifices.

“A Texican is nothing but a human man way out on a limb, this year and next. Maybe for 100 more. But I don’t think it’ll be forever,” Mrs. Jorgensen goes on. “Someday this country’s going to be a fine, good place to be. Maybe it needs our bones in the ground before that time can come.”

There’s a subtext in these lines that destabilizes the Western’s moral center, a politeness deployed by Jorgensen that keeps her from naming what the main characters in the film see as their real enemies: Indians.

In the film, the Comanche chief, Scar, has killed the Jorgensens’ son and Edwards’ family, and abducted his niece. Edwards and the rest of Company A of the Texas Rangers must find her. Their quest takes them across the most treacherous stretches of desert, a visually rich landscape that’s both glorious in its beauty and perilous given the presence of Comanche and other Indigenous people. In the world of the Western, brutality is banal, the dramatic landscape a backdrop for danger where innocent pioneers forge a civilization in the heart of darkness.

The themes of the Western are embodied by figures like Edwards: As a Texas Ranger, he represents the heroism of no-holds-barred policing that justifies conquest and colonization. While the real Texas Rangers’ history of extreme violence against communities of color is well-documented, in the film version, these frontier figures, like the Texas Rangers in The Searchers or in the long-running television show The Lone Ranger, have always been portrayed as sympathetic characters. Edwards is a cowboy with both a libertarian, “frontier justice” vigilante ethic and a badge that puts the law on his side, and stories in the Western are understood to be about the arc of justice: where the handsome, idealized male protagonist sets things right in a lawless, uncivilized land.

The Western has long been built on myths that both obscure and promote a history of racism, imperialism, toxic masculinity, and violent colonialism. For Westerns set in Texas, histories of slavery and dispossession are even more deeply buried. Yet the genre endures. Through period dramas and contemporary neo-Westerns, Hollywood continues to churn out films about the West. Even with contemporary pressures, the Western refuses to transform from a medium tied to profoundly conservative, nation-building narratives to one that’s truly capable of centering those long victimized and villainized: Indigenous, Latinx, Black, and women characters. Rooted in a country of contested visions, and a deep-seated tradition of denial, no film genre remains as quintessentially American, and Texan, as the Western, and none is quite so difficult to change.

*

With origins in the dime and pulp novels of the late 19th century, the Western first took to the big screen in the silent film era. The Great Train Robbery, a 1903 short, was perhaps the genre’s first celluloid hit, but 1939’s Stagecoach, starring Wayne, ushered in a new era of critical attention, as well as huge commercial success. Chronicling the perilous journey of a group of strangers riding together through dangerous Apache territory in a horse-drawn carriage, Stagecoach is widely considered to be one of the greatest and most influential Westerns of all time. It propelled Wayne to stardom.

During the genre’s golden age of the 1950s, more Westerns were produced than films of any other genre. Later in the 1960s, the heroic cowboy character—like Edwards in The Searchers—grew more complex and morally ambiguous. Known as “revisionist Westerns,” the films of this era looked back at cinematic and character traditions with a more critical eye. For example, director Sam Peckinpah, known for The Wild Bunch (1969), interrogated corruption and violence in society, while subgenres like spaghetti Westerns, named because most were directed by Italians, eschewed classic conventions by playing up the dramatics through extra gunfighting and new musical styles and creating narratives outside of the historical context. Think Clint Eastwood’s The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly (1966).

The Great Train Robbery (1903), a short silent film, was perhaps the first iconic Western.

In the wake of the anti-war movement and the return of the last U.S. combat forces from Vietnam in 1973, Westerns began to decline, replaced by sci-fi action films like Star Wars (1977). But in the 1990s, they saw a bit of rebirth, with Kevin Costner’s revisionist Western epic Dances With Wolves (1990) and Eastwood’s Unforgiven (1992) winning Best Picture at the Academy Awards. And today, directors like the Coen brothers (No Country for Old Men, True Grit) and Taylor Sheridan (Hell or High Water, Wind River, Sicario) are keeping the genre alive with neo-Westerns set in modern times.

Still, the Old West looms large, says cultural critic and historian Richard Slotkin. Today’s Western filmmakers know they are part of a tradition and take the task seriously, even the irreverent ones like Quentin Tarantino. Tarantino called Django Unchained (2012) a spaghetti Western and, at the same time, “a Southern.” Tarantino knows that the genre, like much of American film, is about violence, and specifically racialized violence: The film, set in Texas, Tennessee, and Mississippi, flips the script by putting the gun in the hand of a freed slave.

Slotkin has written a series of books that examine the myth of the frontier and says that stories set there are drawn from history, which gives them the authority of being history. “A myth is an imaginative way of playing with a problem and trying to figure out where you draw lines, and when it’s right to draw lines,” he says. But the way history is made into mythology is all about who’s telling the story.

Slotkin’s work purports that the logic of westward expansion is, when boiled down to its basic components, “regeneration through violence.” Put simply: Kill or die. The very premise of the settling of the West is genocide. Settler colonialism functions this way; the elimination of Native people is its foundation. It’s impossible to talk about the history of the American West and of Texas without talking about violent displacement and expropriation.

“The Western dug its own hole,” says Adam Piron, a film programmer at the Sundance Indigenous Institute and a member of the Kiowa and Mohawk tribes. In his view, the perspectives of Indigenous people will always be difficult to express through a form tied to the myth of the frontier. Indigenous filmmakers working in Hollywood who seek to dismantle these representations, Piron says, often end up “cleaning somebody else’s mess … And you spend a lot of time explaining yourself, justifying why you’re telling this story.”

While the Western presents a highly manufactured, racist, and imperialist version of U.S. history, in Texas, the myth of exceptionalism is particularly glorified, perpetuating the belief that Texas cowboys, settlers, and lawmen are more independent, macho, and free than anywhere else. Texas was an especially large slave state, yet African Americans almost never appear in Texas-based Westerns, a further denial of histories. In The Searchers, Edwards’ commitment to the white supremacist values of the South is even stronger than it is to the state of Texas, but we aren’t meant to linger on it. When asked to make an oath to the Texas Rangers, he replies: “I figure a man’s only good for one oath at a time. I took mine to the Confederate States of America.” The Civil War scarcely comes up again.

The Texas Ranger is a key figure in the universe of the Western, even if Ranger characters have fraught relationships to their jobs, and the Ranger’s proliferation as an icon serves the dominant Texas myth. More than 300 movies and television series have featured a Texas Ranger. Before Chuck Norris’ role in the TV series Walker, Texas Ranger (1993-2001), the most famous on-screen Ranger was the titular character of The Lone Ranger (1949-1957). Tonto, his Potawatomi sidekick, helps the Lone Ranger fight crime in early settled Texas.

Meanwhile, the Ranger’s job throughout Texas history has included acting as a slave catcher and executioner of Native Americans. The group’s reign of terror lasted well into the 20th century in Mexican American communities, with Rangers committing a number of lynchings and helping to dispossess Mexican landowners. Yet period dramas like The Highwaymen (2019), about the Texas Rangers who stopped Bonnie and Clyde, and this year’s ill-advised reboot of Walker, Texas Ranger on the CW continue to valorize the renowned law enforcement agency. There is no neo-Western that casts the Texas Ranger in a role that more closely resembles the organization’s true history: as a villain.

The Coen brothers’ No Country for Old Men (2007) ushered in the era of neo-Westerns set in modern times.

Ushered in by No Country for Old Men (2007), also set in Texas, the era of neo-Westerns has delivered films that take place in a modern, overdeveloped, contested West. Screenwriter Taylor Sheridan’s projects attempt to address racialized issues around land and violence, but they sometimes fall into the same traps as older, revisionist Westerns—the non-white characters he seeks to uplift remain on the films’ peripheries. In Wind River (2017), the case of a young Indigenous woman who is raped and murdered is solved valiantly by action star Jeremy Renner and a young, white FBI agent played by Elizabeth Olsen. Sheridan’s attempt to call attention to the epidemic of missing and murdered Indigenous women still renders Indigenous women almost entirely invisible behind the images of white saviors.

There are directors who are challenging the white male gaze of the West, such as Chloé Zhao, whose recent film Nomadland dominated the 2021 Academy Award nominations. In 2017, Zhao’s film The Rider centered on a Lakota cowboy, a work nested in a larger cultural movement in the late 2010s that highlighted the untold histories of Native cowboys, Black cowboys, and vaqueros, historically Mexican cowboys whose ranching practices are the foundation of the U.S. cowboy tradition. And Concrete Cowboy, directed by Ricky Staub and released on Netflix in April, depicts a Black urban horse riding club in Philadelphia. In taking back the mythology of the cowboy, a Texas centerpiece and symbol, perhaps a new subgenre of the Western is forming.

Despite new iterations, the Western has not been transformed. Still a profoundly patriotic genre, the Western is most often remembered for its classics, which helped fortify the historical narrative that regeneration through violence was necessary for the forging of a nation. In Texas, the claim made by Mrs. Jorgensen in The Searchers remains a deeply internalized one: The history of Texas is that of a land infused with danger, a land that required brave defenders, and a land whose future demanded death to prosper.

In Westerns set in the present day, it feels as if the Wild West has been settled but not tamed. Americans still haven’t learned how to live peacefully on the land, respect Indigenous people, or altogether break out of destructive patterns of domination. The genre isn’t where most people look for depictions of liberation and inclusion in Texas. Still, like Texas, the Western is a contested terrain with an unclear future. John Wayne’s old-fashioned values are just one way to be; the Western is just one way of telling our story.

This article was first provided on this site.

We hope you found the article above of help and/or of interest. Similar content can be found on our main site: southtxpointofsale.com

Please let me have your feedback below in the comments section.

Let us know what topics we should write about for you in the future.

youtube

#Point of Sale#harbortouch Lighthouse#harbortouch Pos#lightspeed Restaurant#point of sale#shopkeep Reviews#shopkeep Support#toast Point Of Sale#toast Pos Pricing#toast Pos Support#touchbistro Pos

1 note

·

View note

Text

News and important updates on POS System Equipment & POS.

Scenes from The Searchers (1956), starring John Wayne and set during the Texas-Indian Wars. The film is considered one of the most influential Westerns ever made.

“It just so happens we be Texicans,” says Mrs. Jorgensen, an older woman wearing her blond hair in a tight bun, to rough-and-tumble cowboy Ethan Edwards in the 1956 film The Searchers. Mrs. Jorgensen, played by Olive Carey, and Edwards, played by John Wayne, sit on a porch facing the settling dusk sky, alone in a landscape that is empty as far as the eye can see: a sweeping desert vista painted with bright orange Technicolor. Set in 1868, the film lays out a particular telling of Texas history, one in which the land isn’t a fine or good place yet. But, with the help of white settlers willing to sacrifice everything, it’s a place where civilization will take root. Nearly 90 years after the events depicted in the film, audiences would come to theaters and celebrate those sacrifices.

“A Texican is nothing but a human man way out on a limb, this year and next. Maybe for 100 more. But I don’t think it’ll be forever,” Mrs. Jorgensen goes on. “Someday this country’s going to be a fine, good place to be. Maybe it needs our bones in the ground before that time can come.”

There’s a subtext in these lines that destabilizes the Western’s moral center, a politeness deployed by Jorgensen that keeps her from naming what the main characters in the film see as their real enemies: Indians.

In the film, the Comanche chief, Scar, has killed the Jorgensens’ son and Edwards’ family, and abducted his niece. Edwards and the rest of Company A of the Texas Rangers must find her. Their quest takes them across the most treacherous stretches of desert, a visually rich landscape that’s both glorious in its beauty and perilous given the presence of Comanche and other Indigenous people. In the world of the Western, brutality is banal, the dramatic landscape a backdrop for danger where innocent pioneers forge a civilization in the heart of darkness.

The themes of the Western are embodied by figures like Edwards: As a Texas Ranger, he represents the heroism of no-holds-barred policing that justifies conquest and colonization. While the real Texas Rangers’ history of extreme violence against communities of color is well-documented, in the film version, these frontier figures, like the Texas Rangers in The Searchers or in the long-running television show The Lone Ranger, have always been portrayed as sympathetic characters. Edwards is a cowboy with both a libertarian, “frontier justice” vigilante ethic and a badge that puts the law on his side, and stories in the Western are understood to be about the arc of justice: where the handsome, idealized male protagonist sets things right in a lawless, uncivilized land.

The Western has long been built on myths that both obscure and promote a history of racism, imperialism, toxic masculinity, and violent colonialism. For Westerns set in Texas, histories of slavery and dispossession are even more deeply buried. Yet the genre endures. Through period dramas and contemporary neo-Westerns, Hollywood continues to churn out films about the West. Even with contemporary pressures, the Western refuses to transform from a medium tied to profoundly conservative, nation-building narratives to one that’s truly capable of centering those long victimized and villainized: Indigenous, Latinx, Black, and women characters. Rooted in a country of contested visions, and a deep-seated tradition of denial, no film genre remains as quintessentially American, and Texan, as the Western, and none is quite so difficult to change.

*

With origins in the dime and pulp novels of the late 19th century, the Western first took to the big screen in the silent film era. The Great Train Robbery, a 1903 short, was perhaps the genre’s first celluloid hit, but 1939’s Stagecoach, starring Wayne, ushered in a new era of critical attention, as well as huge commercial success. Chronicling the perilous journey of a group of strangers riding together through dangerous Apache territory in a horse-drawn carriage, Stagecoach is widely considered to be one of the greatest and most influential Westerns of all time. It propelled Wayne to stardom.

During the genre’s golden age of the 1950s, more Westerns were produced than films of any other genre. Later in the 1960s, the heroic cowboy character—like Edwards in The Searchers—grew more complex and morally ambiguous. Known as “revisionist Westerns,” the films of this era looked back at cinematic and character traditions with a more critical eye. For example, director Sam Peckinpah, known for The Wild Bunch (1969), interrogated corruption and violence in society, while subgenres like spaghetti Westerns, named because most were directed by Italians, eschewed classic conventions by playing up the dramatics through extra gunfighting and new musical styles and creating narratives outside of the historical context. Think Clint Eastwood’s The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly (1966).

The Great Train Robbery (1903), a short silent film, was perhaps the first iconic Western.

In the wake of the anti-war movement and the return of the last U.S. combat forces from Vietnam in 1973, Westerns began to decline, replaced by sci-fi action films like Star Wars (1977). But in the 1990s, they saw a bit of rebirth, with Kevin Costner’s revisionist Western epic Dances With Wolves (1990) and Eastwood’s Unforgiven (1992) winning Best Picture at the Academy Awards. And today, directors like the Coen brothers (No Country for Old Men, True Grit) and Taylor Sheridan (Hell or High Water, Wind River, Sicario) are keeping the genre alive with neo-Westerns set in modern times.

Still, the Old West looms large, says cultural critic and historian Richard Slotkin. Today’s Western filmmakers know they are part of a tradition and take the task seriously, even the irreverent ones like Quentin Tarantino. Tarantino called Django Unchained (2012) a spaghetti Western and, at the same time, “a Southern.” Tarantino knows that the genre, like much of American film, is about violence, and specifically racialized violence: The film, set in Texas, Tennessee, and Mississippi, flips the script by putting the gun in the hand of a freed slave.

Slotkin has written a series of books that examine the myth of the frontier and says that stories set there are drawn from history, which gives them the authority of being history. “A myth is an imaginative way of playing with a problem and trying to figure out where you draw lines, and when it’s right to draw lines,” he says. But the way history is made into mythology is all about who’s telling the story.

Slotkin’s work purports that the logic of westward expansion is, when boiled down to its basic components, “regeneration through violence.” Put simply: Kill or die. The very premise of the settling of the West is genocide. Settler colonialism functions this way; the elimination of Native people is its foundation. It’s impossible to talk about the history of the American West and of Texas without talking about violent displacement and expropriation.

“The Western dug its own hole,” says Adam Piron, a film programmer at the Sundance Indigenous Institute and a member of the Kiowa and Mohawk tribes. In his view, the perspectives of Indigenous people will always be difficult to express through a form tied to the myth of the frontier. Indigenous filmmakers working in Hollywood who seek to dismantle these representations, Piron says, often end up “cleaning somebody else’s mess … And you spend a lot of time explaining yourself, justifying why you’re telling this story.”

While the Western presents a highly manufactured, racist, and imperialist version of U.S. history, in Texas, the myth of exceptionalism is particularly glorified, perpetuating the belief that Texas cowboys, settlers, and lawmen are more independent, macho, and free than anywhere else. Texas was an especially large slave state, yet African Americans almost never appear in Texas-based Westerns, a further denial of histories. In The Searchers, Edwards’ commitment to the white supremacist values of the South is even stronger than it is to the state of Texas, but we aren’t meant to linger on it. When asked to make an oath to the Texas Rangers, he replies: “I figure a man’s only good for one oath at a time. I took mine to the Confederate States of America.” The Civil War scarcely comes up again.

The Texas Ranger is a key figure in the universe of the Western, even if Ranger characters have fraught relationships to their jobs, and the Ranger’s proliferation as an icon serves the dominant Texas myth. More than 300 movies and television series have featured a Texas Ranger. Before Chuck Norris’ role in the TV series Walker, Texas Ranger (1993-2001), the most famous on-screen Ranger was the titular character of The Lone Ranger (1949-1957). Tonto, his Potawatomi sidekick, helps the Lone Ranger fight crime in early settled Texas.

Meanwhile, the Ranger’s job throughout Texas history has included acting as a slave catcher and executioner of Native Americans. The group’s reign of terror lasted well into the 20th century in Mexican American communities, with Rangers committing a number of lynchings and helping to dispossess Mexican landowners. Yet period dramas like The Highwaymen (2019), about the Texas Rangers who stopped Bonnie and Clyde, and this year’s ill-advised reboot of Walker, Texas Ranger on the CW continue to valorize the renowned law enforcement agency. There is no neo-Western that casts the Texas Ranger in a role that more closely resembles the organization’s true history: as a villain.

The Coen brothers’ No Country for Old Men (2007) ushered in the era of neo-Westerns set in modern times.

Ushered in by No Country for Old Men (2007), also set in Texas, the era of neo-Westerns has delivered films that take place in a modern, overdeveloped, contested West. Screenwriter Taylor Sheridan’s projects attempt to address racialized issues around land and violence, but they sometimes fall into the same traps as older, revisionist Westerns—the non-white characters he seeks to uplift remain on the films’ peripheries. In Wind River (2017), the case of a young Indigenous woman who is raped and murdered is solved valiantly by action star Jeremy Renner and a young, white FBI agent played by Elizabeth Olsen. Sheridan’s attempt to call attention to the epidemic of missing and murdered Indigenous women still renders Indigenous women almost entirely invisible behind the images of white saviors.

There are directors who are challenging the white male gaze of the West, such as Chloé Zhao, whose recent film Nomadland dominated the 2021 Academy Award nominations. In 2017, Zhao’s film The Rider centered on a Lakota cowboy, a work nested in a larger cultural movement in the late 2010s that highlighted the untold histories of Native cowboys, Black cowboys, and vaqueros, historically Mexican cowboys whose ranching practices are the foundation of the U.S. cowboy tradition. And Concrete Cowboy, directed by Ricky Staub and released on Netflix in April, depicts a Black urban horse riding club in Philadelphia. In taking back the mythology of the cowboy, a Texas centerpiece and symbol, perhaps a new subgenre of the Western is forming.

Despite new iterations, the Western has not been transformed. Still a profoundly patriotic genre, the Western is most often remembered for its classics, which helped fortify the historical narrative that regeneration through violence was necessary for the forging of a nation. In Texas, the claim made by Mrs. Jorgensen in The Searchers remains a deeply internalized one: The history of Texas is that of a land infused with danger, a land that required brave defenders, and a land whose future demanded death to prosper.

In Westerns set in the present day, it feels as if the Wild West has been settled but not tamed. Americans still haven’t learned how to live peacefully on the land, respect Indigenous people, or altogether break out of destructive patterns of domination. The genre isn’t where most people look for depictions of liberation and inclusion in Texas. Still, like Texas, the Western is a contested terrain with an unclear future. John Wayne’s old-fashioned values are just one way to be; the Western is just one way of telling our story.

This article was first provided on this site.

We hope you found the article above of help and/or of interest. Similar content can be found on our main site: southtxpointofsale.com

Please let me have your feedback below in the comments section.

Let us know what topics we should write about for you in the future.

youtube

#Point of Sale#harbortouch Lighthouse#harbortouch Pos#lightspeed Restaurant#point of sale#shopkeep Reviews#shopkeep Support#toast Point Of Sale#toast Pos Pricing#toast Pos Support#touchbistro Pos

0 notes