#civilwarincolor

Photo

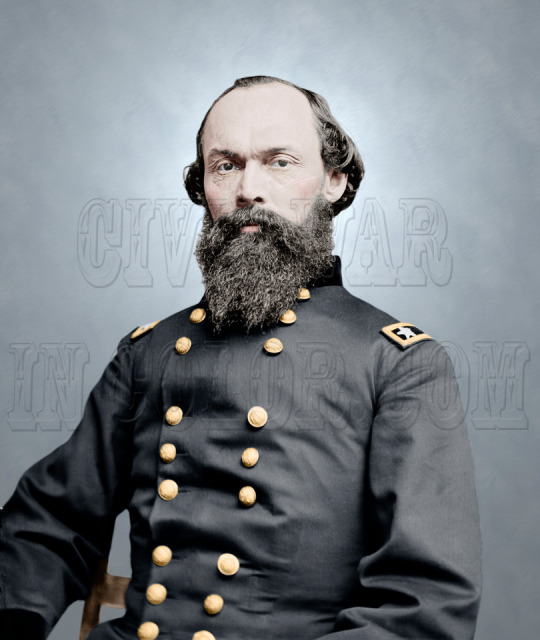

U.S. Gen. Gordan Granger

“Men and women screamed, ‘We’s free! We’s free!’” – Juneteenth celebrants; wharves, Galveston, TX

In June of 1865, Texas was in chaos. Texas had never been conquered during the War. It had recently been an independent Country. The 13th Amendment, abolishing slavery, would not be ratified until December 6, 1865. More to the point, the economy depended on slave labor. Newspapers speculated that a form of forced black labor would continue.

The Federal government was concerned about being overwhelmed by newly freed slaves flocking to U.S. outposts. Furthermore, in violation of the Monroe Doctrine, France had installed a puppet emperor in April of 1864. Former confederates were contemplating exile in Mexico to fight for Emperor Maximilian.

On June 17, 1865, U.S. Gen. Gordon Granger arrived in Galveston, Texas as the commander of the newly formed District of Texas. Today, Granger is best known for coming to US Gen George “Rock of Chickamauga” Thomas’s aid during the Battle of Chickamauga, GA .

To settle the slavery issue, it would have been expedient to read Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation. Instead Granger composed General Order No. 3, read from the balcony of Ashton Villa on June 19th.

“The people of Texas are informed that, in accordance with a proclamation from the Executive of the United States, all slaves are free. This involves an absolute equality of personal rights and rights of property between former masters and slaves, and the connection heretofore existing between them becomes that between employer and hired labor. The freedmen are advised to remain quietly at their present homes and work for wages. They are informed that they will not be allowed to collect at military posts and that they will not be supported in idleness either there or elsewhere.”

The Order was not graciously received by all. It was reported that a slave patrol whipped one hundred celebrants. A jubilant newly freed slave was told by his former master that if he jumped again, “I will shoot you between the eyes.”

The reverberations from Order No. 3 never really ceased. It was the first official news of slavery’s end and just as importantly, specifying equality of rights.

Initially, Juneteenth was a holiday celebrated by former slaves and their descendants. It became an official Texas holiday in 1979.

#juneteenth#civilwargeneral#civilwarcolorphoto#civilwarincolor#historyincolor#historyinfullcolor#gengordangranger#gengranger

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Firing a Quaker Gun, Centreville, VA 1862

"[I]t was a favorite trick to run it out into the center of the road and go through the motions of loading a gun and pointing it at the enemy, who promptly stampeded, under the impression that we had a piece of artillery with us" - PVT Edgar Warfield, 17th Va., Munson's Hill, Va.

"Quaker Guns" - logs, usually painted black, have been used to deceive the enemy in North America since the American Revolution. Adding wheels to the log, made it virtually impossible to discern it was a fake from a distance. During the Civil War, both sides, including civilians would hoodwink their foe using logs, stove-pipes, kegs and more.

After the First Battle of Manassas, Va. on July 21, 1861, Col. J.E.B. Stuart's troops ended up approximately six miles from Washington D.C. at Munson's Hill, Va.. While Gen. Joseph Johnston reorganized the Confederate Army of the Potomac, Stuart dug earthworks that appeared to be up to 15' high and erected signal stations. Lacking actual cannons, he placed Quaker Guns in the trenches.

As Gen. James Longstreet later recalled, "the authorities allowed me but one battery. . . we collected a number of old wagon-wheels and mounted on them stove-pipes of different calibre, till we had formidable-looking batteries, some large enough of calibre to threaten Alexandria, and even the National Capitol and Executive Mansion."

For the next two months, Gen. George McClellan drilled the Army of the Potomac at the capital. Thaddeus Lowe would send up his observation balloons to check out the situation. Stuart was promoted to the rank of Brig. General. The Confederates kept busy firing at anyone approaching on the broad, flat plain called Bailey's Crossings below and the observation balloons above.

As there weren’t any major battles being fought, the newspapers focused on the Confederates above Washington, who alarmed everyone living at the capital by flying "an immense Confederate flag—the red, white, and blue stripes in which are at least five feet wide each—is the most prominent object upon the top of the eminence." According to the New York Times, it "was visible with a glass from the top of the shiphouse at the Navy-yard" in Washington D.C..

Longstreet recollected, "[w]e were provokingly near Washington, with orders not to attempt to advance even to Alexandria." Johnson on the other hand considered the Munson's Hill position as defensively unsound and logistically difficult to keep supplied. McClellan, by twice sending out heavy armed reconnaissance parties to probe the rebel lines, may have convinced Johnson that enough was enough. It was time for the troops to fall back.

On September 28, 1861, the Confederates abandoned Munson's Hill, leaving behind their Quaker Guns. After having been terrified by logs, the North proceed to mock the army in the newspapers and by song. McClellan was the target of "The Bold Engineer" and the situation was declared a "humbug - worse that a Bull-run" in the song, "The Battle of the Stoves-Pipes". However, as the war proceeded, the newspapers began to defend the generals by pointing out that without risking being fired upon, it is difficult to discern logs from actual cannons.

#quakergun#munsonhill#civilwargeneral#genjebstuart#genlongstreet#genjoejohnston#genjohnston#genMcClellan#thadduslowe#historyinfullcolor#historyincolor#civilwarincolor#civilwarcolorphoto#civilwarphoto

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

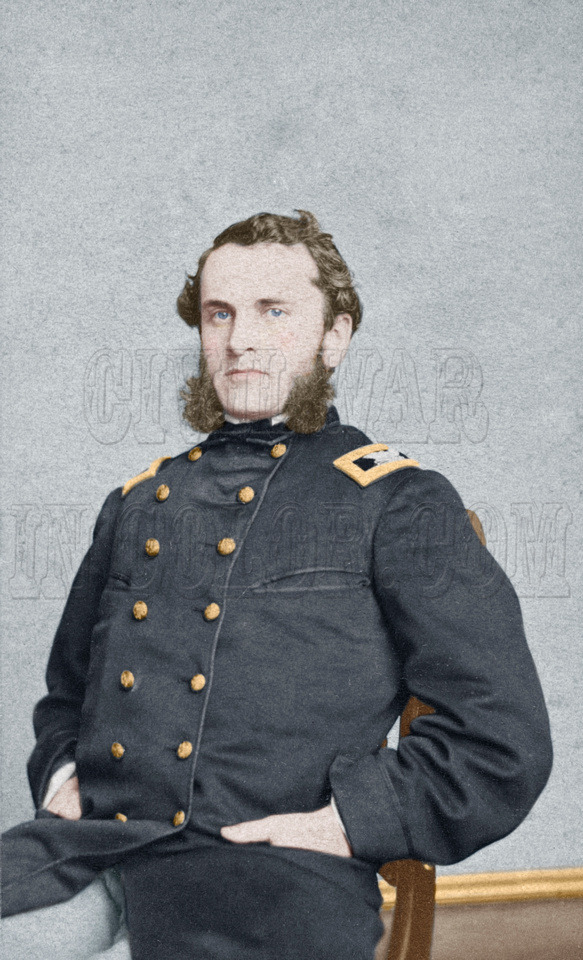

Adm. David Farragut & Gen. Gordon Granger

“Hold the Fort. …. Stop communicating with the enemy; all terms or stipulations made by you are annulled.” - C.S. Brig. Gen. Richard Page

By August of 1864, the Federal blockade had managed to shutter all but two major Confederate ports, Wilmington, N.C. and Mobile Bay, Ala.

To close Mobile Bay, U.S. Adm. David Farragut and U.S. Gen Gordon Granger headed a joint land sea campaign. The Army was tasked with capturing the twin masonry fortifications positioned at the mouth of the Bay, Ft. Morgan on a spit of land known as Mobile Point, designed to guard the shipping channel and Ft. Gaines on Dauphin Island, offering sheltered anchorage.

Today, West Point graduate U.S. Gen. Gordon Granger is best known for coming to the aid of U.S. Gen. George “Rock of Chickamauga” Thomas during the Battle of Chickamauga, Ga. and freeing the slaves of Texas on June 19, 1865, resulting in the holiday known as “Juneteenth”. Granger was candid and “for the mere tinsel of rank he had no respect”. He was a stickler for following military procedure but earned the ire of U.S. Gen. Ulysses Grant by refusing to move without basic supplies for his men. Granger used political pull to return to the field.

On August 3, Granger and 1,500 men landed on Dauphin Island, seven miles from Gaines, intent on making the Fort a staging area for taking Mobile. On the 4th, they were within 1,200 yards.

On the 5th, Farragut’s 199-gun fleet attacked. As agreed, Granger’s troops began shelling the Fort with six 3-in Rodman guns. His sharpshooters climbed the surrounding sand dunes, shooting down into Gaines. From the north, came shells from monitors USS Chickasaw and USS Winnebago.

C.S. Col. Charles Anderson led the 21st Ala., reservists and cadets from Pelham Military Academy, Ala. that made up the 800-man garrison of Ft. Gaines. The Federal government had almost finished remodeling Gaines before the War began. Armed with 26 guns, including four 10-inch columbiad guns, the 22-foot high walls were designed to survive a six-month siege, had a rain catchment system and the latrines were flushed by the tide. It would come as a shock to her defenders that rifled guns had made brick walls obsolete.

On the 6th, the officers petitioned Anderson to surrender. Although inclined to hold out, Anderson realized, “We could render Mobile no assistance. We could render Morgan no assistance, and we could have done no harm to the enemy.” Furthermore, he could have a mutiny on his hands. He sent word to Farragut for honorable surrender terms.

At 8:00 a.m. on the 8th, Anderson formally surrendered Gaines, the POWs were sent to New Orleans, La. and the Stars and Stripes flew above.

“I found the fort in excellent order,” reported Cpt. Miles McAlester, Chief Engineer. He noted that its defenses, “… was utterly weak and inefficient against our attack (land and naval), which would have taken all its fronts in front, enfilade, and reverse.”

Commanding Ft. Morgan and all Mobile Bay’s defenses was C.S. Brig. Gen. Richard Page, cousin of C.S. Gen. Robert E. Lee and former Farragut friend. Page spotting the truce boat was livid. He repeatedly sent messages to Anderson to not surrender via boat and telegraph.

C.S.A. President Jefferson Davis vowed to put Anderson on trial if exchanged. Page called the surrender, “… a deed of dishonor and disgrace to its commander and garrison.”

#davidfarragut#admfarragut#admiralfarragut#gengranger#gengordongranger#battlemobilebay#battleofmobilebay#ftgaines#ftmorgan#dauphinisland#usschickasaw#usswinnebago#colcharlesanderson#milesmcalester#genrichardpage#genpage#historyinfullcolor#historyincolor#civilwarincolor#civilwarcolorphoto#civilwarphoto#pelhammilitaryacademy

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

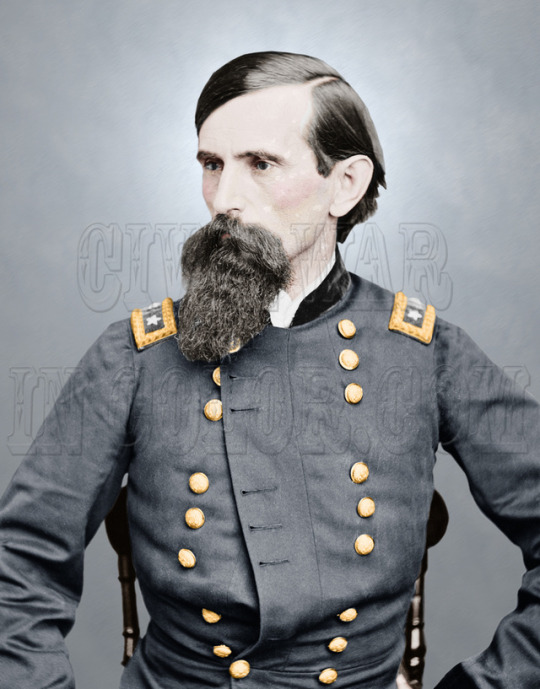

U.S. Gen. Strong Vincent

“What death more glorious can any man desire than to die on the soil of old Pennsylvania fighting for that flag?” – Col. Strong Vincent

On July 2, 1863, near the George Weikert house on Cemetery Ridge, U.S. Col Strong Vincent, was waiting at the head of the 3rd brigade, 1st division, during the second day of the Battle of Gettysburg, Penn.

Noticing U.S. Gen George Sykes’ aide, Vincent rode forward asking, "Captain, what are your orders?" The captain replied, "Where is General [James] Barnes?" Vincent said, "What are your orders? Give me your orders" The captain answered, “General [George] Sykes told me to direct General Barnes to send one of his brigades to occupy that hill yonder,” pointing to Little Round Top. Vincent said, "I will take the responsibility of taking my brigade there."

Although a lawyer in civilian life, Vincent knew to position his men not on top of the summit but on the crest below. As the battle raged below at Devil’s Den, Vincent concluded the top priority was to defend the western and southern slopes. He selected a ledge, known afterwards as Vincent’s Spur, as the spot to place his men.

Shells began exploding on either side of Vincent and Pvt. Oliver Norton, who bore the brigade headquarters flag. “They are firing at the flag, go behind the rocks with it,” yelled Vincent. As the Confederates approached from the woods, Vincent gave instructions and encouragement as he positioned the 44th N.Y., 83rd Penn., 20th Maine and the 16th Mich. Col. Joshua Chamberlain, 20th Maine, was told, “this is the extreme left of our general line” which he was to “hold that ground at all hazards.”

The right flank came under assault from the 4th Ala., 4th and 5th Texas. From the Spur “… a sheet of smoke and flames burst from our whole line.” Dead and wounded attackers tumbled intertwined downhill. “Now it was expected that our men having tried it and seeing the impossibility of taking the place would have refused to go in again”, recalled a 5th Texas soldier. “But no, they tried it a second time”.

From the summit, U.S. Gen. Gouverneur Warren spotted a 5th Corps column passing below. Riding down to intercept it, Warren recognized the man at its head, Col Patrick O’Rourke, 140th N.Y. “Paddy, give me a regiment”, Warren said. O’Rourke protested that U.S. Gen. Stephen Weed, 3rd brigade, 2nd Division, expected him elsewhere. “Never mind that,” Warren interjected. “Bring your regiment up here and I will take the responsibility.”

On the far right, mistakenly believing a retreat had been ordered, a third of the 16th Mich. followed its flag towards the rear. The rebels surged towards the collapsing line. Vincent waving his riding crop, leaped onto a rocky perch yelling, “Don’t give an inch boys. Don’t give an inch!” Vincent dropped, shot in the thigh, mortally wounded.

Into the breech arrived the 140th, with unloaded guns. “No time now, Paddy, for alignment,” Warren shouted. “Take your men immediately into action.” O’Rourke ran forward. “Here they are men”, he yelled. “Commence firing.” The lines erupted as both sides obeyed. O’Rourke was mortally shot in the neck as his men rushed forward, energizing the entire federal line.

The fight ended with the 20th Maine’s Col. Joshua Chamberlain leading the charge to drive the confederates off Little Round top. On the evening of July 2nd, U.S. Maj. Gen. George Meade recommended the promotion of Vincent to Brigadier General. His commission was read to him on his deathbed.

Previously, Vincent had written to his wife, "If I fall, remember you have given your husband to the most righteous cause that ever widowed a woman."

#Vincentstrong#genstrong#colstrong#civilwargeneral#civilwarcolorphoto#civilwarphoto#battleofgettysburg#gettysburgcivilwar#civilwarincolor#historyinfullcolor#historyincolor#littleroundtop#joshuachamberlain#gouverneurwarren#genwarren

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

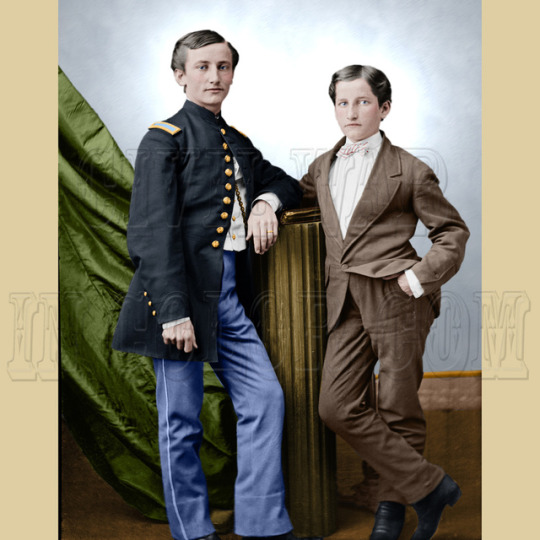

Pres. Abraham Lincoln’s sons Willie and Tad Lincoln with their cousin Lockwood Todd - 1861

"It is my pleasure that my children are free, happy and unrestrained by parental tyranny. Love is the chain whereby to bind a child to its parents." Abraham Lincoln

Both Mary and Abraham Lincoln, for different reasons, didn't have happy childhoods. To the displeasure of others, both parents were known to indulge their children.

In October of 1847, as the family journeyed to Washington D.C., they stopped in Lexington to visit the Todd relatives.

By chance, Mrs. Todd's nephew, Joseph Humphreys had been traveling on the same train as the Lincolns. Arriving at the Todd home before them, Humphreys immediately began describing his journey:

"Aunt Betsy, I was never so glad to get off a train in my life. There were two lively youngsters on board who kept the whole train in turmoil, and their long legged father, instead of spanking the brats, looked please as Punch and aided and abetted (them) in their mischief."

As he looked out of the window, he could see the family getting out of a carriage. Horrified, Humphreys exclaimed, "Good Lord! There they are now!" He was not seen again at the Todd's until after the Lincolns left.

Not everyone had the same reaction to the Lincolns as Humphreys. For the next three weeks the Lincolns visited Mary's many relatives. Lincoln romped with Bobby, Eddie and Emilie, Mary's nine-year-old half-sister. The future widow of Confederate General Ben Helm recalled that at the end of their time together, "we hated to see them go".

#abrahamlincoln#preslincoln#willielincoln#tadlincoln#marylincoln#emiliehelm#emilietoddhelm#fathersday#historyinfullcolor#historyincolor#civilwarincolor#civilwarcolorphoto#civilwarphoto#lockwoodtodd

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Sergeant Johnny Clem (later Lt.); Was Sgt at age 13 (image from 1870's) w-Bro.

“… We who fought to kill each other were really never enemies. It was a war of cannon against fortress, of rifle against trench, but never of man against his brother man!” - Col Johnny Clem aka "The Drummer boy of Chickamauga"

In honor of Memorial Day, here is an excerpt from an interview Col John Clem gave a Washington D.C. newspaper reporter in 1914.

Clem had been famous since he was 12 years old as "The Drummer boy of Chickamauga". Clem was asked, on the occasion of Memorial Day, what memory was uppermost in his mind that day. Clem gently responded:

“My memory pictures today what my kid eyes saw fifty-one years ago today, a soldier in blue an a soldier in gray, shaking hands like two loving comrades between the trenches, swapping tobacco and coffee. In the morning they were to stab each other brutally with bayonets in a fierce hand-to-hand fight for those very trenches."

.... “Yet what I like to think of first on Memorial Day is not the bloody fight, but that tender scene preceding it, which showed me that after all, man to man, we soldiers of the north and of the south were friends and brothers always. We of the north hated that which they fought for, but we did not hate them personally, nor they us.

It is the great tragedy of those bloody deaths we brought each other, but not because of hatred for each other, but for the sake of a principle, that we must think of on this sacred Memorial Day.”

#johnclem#drummerboyofchickamauga#civil war images#civilwarincolor#historyinfullcolor#historyincolor#memorialday

1 note

·

View note

Photo

General Rufus Ingalls coach dog; City Point, Virginia, March 1865

“I am General Ingalls’s dog; whose pup are you?”

In City Point, Va., U.S. Gen. Rufus Ingalls’s popular dog became the focus of photographers. U.S. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant’s and cavalry officer’s horses would pose for pictures. Fighting units would include their mascots when they were photographed. The dog would become one of the few pets to be photographed at least five times during the Civil War.

In the 1860’s Dalmatians were a rare breed in America. Furthermore, dogs were uncommon in an army camp. Ingalls had returned from a trip to Washington D.C. with the Dalmatian. The men enjoyed seeing the popular officer accompanied by his friend in fur.

When Grant ran into his former West Point classmate Ingalls, he too would remark on the dog.

In Horace Porter’s book, “Campaigning with Grant”, we have a report of Grant-Ingalls interaction that includes the dog.

“One evening, as the general was sitting in front of his quarters, Ingalls came up to have a chat with him, and was followed by the dog, which sat down in the usual place at its master’s feet.

“The animal squatted upon its hind quarters, licked its chops, pricked up its ears, and looked first at one officer and then at the other, as if to say: ‘I am General Ingalls’s dog; whose pup are you?’

“In the course of his remarks General Grant took a look at the animal, and said: ‘Well, Ingalls, what are your real intentions in regard to that dog? Do you expect to take it into Richmond with you?’

“Ingalls, who was noted for his dry humor, replied with mock seriousness and an air of extreme patience: ‘I hope to; it is said to come from a long-lived breed.’

“This retort, coupled with the comical attitude of the dog at the time, turned the laugh upon the general, who joined heartily in the merriment, and seemed to enjoy the joke as much as any of the party.”

#civilwargeneral#genrufusingalls#geningallsdog#geningall#citypoint#gengrant#genulyssesgrant#historyinfullcolor#historyincolor#civilwarincolor#civilwarcolorphoto#civilwarphoto

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Major General Lew Wallace; Savior of Cincinnati, Author of Ben Hur

“Think of the earth ten thousand men can move in one day! Then, if the Confederates give us a week, we can get half of Indiana and half of Ohio behind the breastworks." – U.S. Gen. Lew Wallace

On September 1, U.S. Gen. Horatio Wright, cmdr. of the Dept. of Ohio, requested U.S. Gen. Lew Wallace take command of the troops in Cincinnati, Ohio. It was feared that C.S. Gen. Kirby Smith having captured Richmond, Ky., would now target Cincinnati, the largest city west of Baltimore, Md. and north of New Orleans, La.

Wallace’s staff pointed out, “There is nothing at Cincinnati with which to make a defense – not a solider, not a gun, not a fort. To try must end in failure.”

Wallace, the future author of the 19th century’s bestselling novel Ben-Hur, came up with a plan.

On September 2, he enacted Martial law. Every able-bodied man would be given the choice “to work or fight.” He called in local surveyors and civil engineers to teach them military engineering, so they could construct the riffle pits and breastworks.

On the second day 15,000 men were sent across the river to begin the defenses.

Realizing the ferryboats could not move fast enough, Wallace called in the top local builders requesting construction of a pontoon bridge. They responded that it could be done within 48 hours. “… we will go up into the Licking River and fetch down coal-barges, which, with the help of a steamboat, we will tie and anchor and make into a bridge for you twenty-five feet in width from shore to shore”.

The railroads were running day and night. The foundry at Cincinnati contributed ten Napoleon guns. The arsenal in Indianapolis, Ind. sent all the ordnance they had. Both Ohio and Indiana sent men armed with their best weapons, some of which were Revolutionary War horse pistols.

By the fifth day of the proclamation, 72,000 were prepared to defend the area, 60,000 of them were irregulars a.k.a. the “Squirrel Hunters”. The men were fed by women making sandwiches around the clock.

“If the enemy should not come after all of this fuss,” said a doubting Wallace friend, “you will be ruined.”

On the 10th, C.S. Gen. Henry Heth and his column arrived at Covington. Heth’s intel had Cincinnati defended by logs painted black, hastily dug breastworks and impressed lawyers, doctors, shopkeepers as combatants; “… and that at the first shot they would break for the river.”

Instead of ordering an assault, the rebels looked over the fort, the recently constructed breastworks and the masses of people behind them.

On the morning of the 12th, the Confederates were gone.

#genlewwallace#genhenryheth#genheth#defenseofcincinnati#defenderofcincinnati#saviorofcincinnati#genkirbysmith#genhoratiowright#benhur#civilwargeneral#historyinfullcolor#historyincolor#civilwarincolor#civilwarphoto#civilwarcolorphoto

0 notes