#celestial emporium of benevolent knowledge

Text

I think the most terrifying part of any relationship is the ongoing awareness that you are going to have to trust someone when they appear to like or love you. There is no objective way to check your status with someone, no app that will say "they like you overall but are mad at you right now, specifically for x or y or a vague z thing that you didn't even clock when it was happening. But! if you send them a nice card and small gift, they will forget about it and return to base level affection"

instead, you have to just....keep having a relationship with that person, doing big and small things with or for them, and praying that you will both be brave and evolved enough to raise x/y/z as an issue if it genuinely is problem.

Mortifying ordeal of being known, down to your very gluons, and disliked.

#this is worse with family I think. because I listen to my family talk about how other members#are frustrating or did a thing and isn't that irritating?? that this person is themselves????#(I am not blameless in this; I talk about other members of the family too)#but I am 100% sure I love my family. even talking about how annoying they are! I love them.#I can only hope they love me.#or worse - that they put up with me when I'm in front of them but when I leave...?#I live in terror of being That Person for the next generation.#celestial emporium of benevolent knowledge

368 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

#watched a couple of her videos & the analysis it's really good#just finished reading p&p (after reading a wonderful ff about it) and wanted even more#the author of the channel is a professor for one of the oxford online courses & it's on jane austen...#would love to take it but....350£ ehh#celestial emporium of benevolent knowledge#Youtube

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Forgery, Replica, Fiction: Temporalities of German Renaissance Art (Christopher Wood, 2008)

A book can swiftly win me over with the right kind of deranged table of contents, especially if the ToC is also a "tag yourself" pool

#destructive intimacy with the distant past#pressures on the referential model#hypertrophy of alphabetic choice#strange temporalities of the artifact#krinnposting#celestial emporium of benevolent knowledge#celestialemporiumofbenevolentknowledgeposting

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

I keep hankering to sketch out a Celestial Emporium of Benevolent Knowledge of Eurovision, featuring:

songs I particularly like

songs featuring burning pianos

funny songs

songs that resemble rock and roll from a distance

songs belonging to the English

and so on

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

"On those remote pages [of the Celestial Emporium of Benevolent Knowledge] it is written that animals are divided into

(a) those that belong to the Emperor,

(b) embalmed ones,

(c) those that are trained,

(d) suckling pigs,

(e) mermaids,

(f) fabulous ones,

(g) stray dogs,

(h) those that are included in this classification,

(i) those that tremble as if they were mad,

(j) innumerable ones,

(k) those drawn with a very fine camel's hair brush,

(l) et cetera,

(m) those that have just broken a flower vase,

(n) those that resemble flies from a distance.

- Jorge Luis Borges, The Analytical Language of John Wilkins

______________

Welcome. In this space we collect benevolent knowledge of all kinds, and we categorize it according to the categories established in the Celestial Emporium, we tend to our peryton, and apart from that, we do very little, because this is merely a sideblog.

0 notes

Text

Celestial emporium of benevolent knowledge

Wilkins, a 17th-century philosopher, had proposed a universal language based on a classification system that would encode a description of the thing a word describes into the word itself—for example, Zi identifies the genus beasts; Zit denotes the "difference" rapacious beasts of the dog kind; and finally Zitα specifies dog.

In response to this proposal and in order to illustrate the arbitrariness and cultural specificity of any attempt to categorize the world, Borges describes this example of an alternate taxonomy, supposedly taken from an ancient Chinese encyclopaedia entitled Celestial Emporium of Benevolent Knowledge. The list divides all animals into 14 categories.

Borges' SpanishEnglish translation

pertenecientes al Emperador (those belonging to the Emperor)

embalsamados (embalmed ones)

amaestrados (trained ones)

lechones (suckling pigs)

sirenas (mermaids)

fabulosos (fabled ones)

perros sueltos (stray dogs)

incluidos en esta clasificación (those included in this classification)

que se agitan como locos (those that tremble as if they were mad)

innumerables (innumerable ones)

dibujados con un pincel finísimo

de pelo de camello (those drawn with a very fine camel hair brush)

etcétera (et cetera)

que acaban de romper el jarrón (those that have just broken the vase)

que de lejos parecen moscas (those that from afar look like flies)

Borges claims that the list was discovered in its Chinese source by the translator Franz Kuhn.

0 notes

Text

a brief list of foods i will not eat or not nom nom nom

fennel

deviled eggs

mammal brains

barbecue flavored fritos

structurally unstable sandwiches

sweetbreads

cephalopods

anything in the mayonnaise salad family

served in stemware

#you discuss borges with one octopus and you can never eat takoyaki again#not nom nom nom#not even if compelled by the emperor#spooky face stickers#lists#mumblelard#celestial emporium of benevolent knowledge#borges#takoyaki#cephalopods

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

6 notes

·

View notes

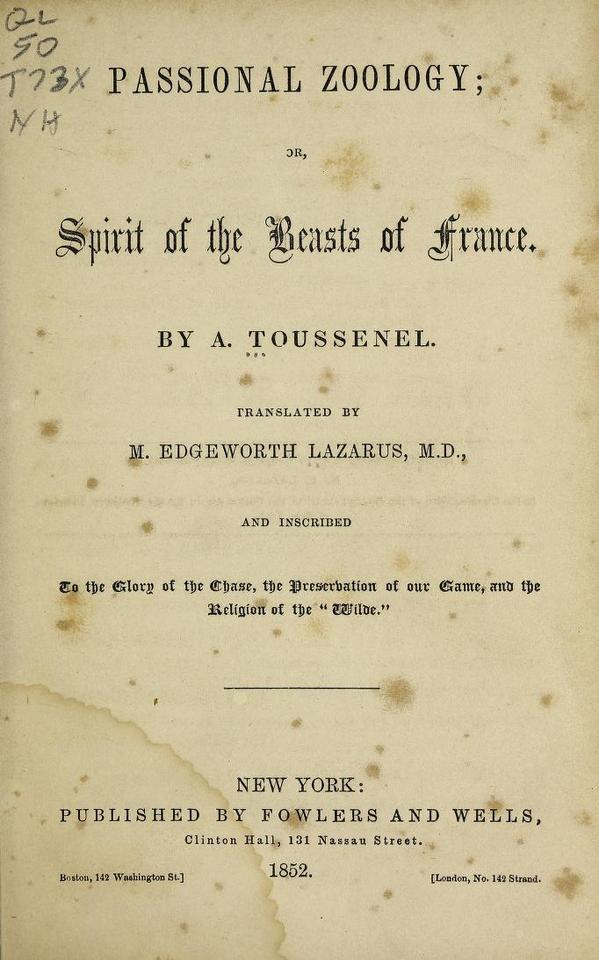

Photo

Alphonse Toussenel, a so-called "utopian socialist", wrote Passional zoology; or, Spirit of the beasts of France in 1852. "[Toussenel]'s studies of natural history served as a vehicle for his political ideas" (according to his Wikipedia article), which may explain his unorthodox and perhaps not particularly objective approach to science. Here are some examples of page headings from Passional zoology.

See the full text in the @biodivlibrary

415 notes

·

View notes

Text

Theorizing Hobohemia

For Chick’s benefit, Darby explained that this outfit had first been formed over twenty years ago, during the Sieges of Paris [in 1871], when manned balloons were often the only way to communicate in or out of the city. As the ordeal went on, it became clear to certain of these balloonists, observing from above and poised ever upon a cusp of mortal danger, how much the modern State depended for its survival on maintaining a condition of permanent siege — through the systematic encirclement of populations, the starvation of bodies and spirits, the relentless degradation of civility until citizen was turned against citizen, even to the point of committing atrocities like those of the infamous petroleurs of Paris. When the Sieges ended, these balloonists chose to fly on, free now of the political delusions that reigned more than ever on the ground, pledged solemnly only to one another, proceeding as if under a world-wide, never-ending state of siege.

- Thomas Pynchon, Against the Day, 2006

“The fact that it is in every way easier for most North Americans to imagine the complete and utter destruction of the planet we currently inhabit than to envision the end of the capitalist order to which the planet gave birth presents certain theoretical and methodological obstacles. In order to explain the dynamics of non-capitalist, non-statist social practices in Depression-era hobo jungles, when the very subject belongs to the genres of nursery rhymes and science fiction, it seems necessary to ask in advance for the reader’s “willing suspension of disbelief,” as Coleridge put it. My argument that British Columbia became home to a “homeland” for beggars is in part a nominalist, source-driven claim: everywhere I turned, archives offered me dusty examples of a multitude of ways of seeing the hobo jungle as an island unto itself, something simultaneously connected to and separate from “society,” whatever one took that to mean, and I will admit to remaining trapped within the logics of separation that it was my fortune to research. These visions were simply too powerful, with many of their authors positioned to effect concrete changes in the shape and character of itinerant life, for me to escape the foundations they erected. In this sense, hobo jungles are represented here as a distinct form of social organization because they were repeatedly made so in the early 1930s.

Nonetheless, my claim that the social organization of jungle life entailed the spatial localization of a fundamental break with contemporaneous capitalogic and governmentality does not depend upon the existence of a shared subjectivity: that is, the thousands of participants involved in building and sustaining this homeland need not have universally or even widely believed that they had created in these spaces an alternative order to liberal-democratic capitalism to have actually done so. In fact, the absence of institutionalized mechanisms of collective consciousness- or identity-formation is one of the fundamental products of, and preconditions for, the jungle way of life. This suggests that the usual metrics of success applied to groups such as multinational corporations, political parties, charitable organizations, and trade unions, organized according to principles other than direct democracy, are of little use here.

In his now famous preface to The Order of Things (1966), Foucault seized upon Borges’s description of a system of classification regarding animals found in an imaginary “Celestial Emporium of Benevolent Knowledge” as raw material that he used to construct his archaeology of the human sciences. Here, against utopias, which “have no real locality,” Foucault conjured the figure of “heterotopias,” which “secretly undermine language, because they make it impossible to name this and that, because they shatter or tangle common names. . . . Heterotopias (such as those to be found so often in Borges) desiccate speech, stop words in their tracks, contest the very possibility of grammar at its source; they dissolve our myths and sterilize the lyricism of our sentences.” The following year, in a lecture exploring the argument that “the present age may be the age of space” rather than time (in this context, a code word for Marxism), Foucault returned to this figure in a different form. Heterotopias now leaped from the page, as cemeteries and gardens, museums and festivals, sailing vessels and the colonies of the New World:

There are . . . probably in every culture, in every civilization, real places, actual places, places that are designed into the very institution of society, which are sorts of actually realized utopias in which the real emplacements, all the other real emplacements that can be found within the culture are, at the same time, represented, contested and reversed, sorts of places that are outside all places, although they are actually localizable.

The Foucault who promises to locate “actually realized utopias” can be placed in the same general lineage as the one a decade later who references “bodies and their pleasures,” “subjugated knowledges,” “limit-experiences,” and “counter discourses” as categories that somehow stand in opposition to elements of the workings of power. Because Foucault offered this concept before his ultra-leftist period of the early 1970s, it is marked as qualitatively different from the more familiar arguments of later years. Foucault’s brief comments not only point us toward some of the prominent discontinuities marked by jungle life but also allow for connections to be forged between the Foucauldian heterotopia and the Marxian realm of freedom.

British Columbia’s Hobohemia, as understood here, fits comfortably within this description of heterotopias as “places that are outside all places” and that gather together a host of discarded, disparate elements “within the culture” in ways that allow for contestation and reversal. Most historians would also accept a general view of hobo jungles as “designed into the very institution of society,” having recognized for decades the centrality of labour mobility to capitalist growth and state expansion, and the unofficial policies of the Dominion government and the railway companies to facilitate this mobility at certain times of the year. More to the point, Vancouver’s relief officer, Colonel H. W. Cooper, initially considered the jungles not as the threat to social order they would later become but as something of a safety valve for the Relief Department. With Reverend Roddan’s First United providing food and counselling, and other private individuals doing their part, the municipality could avoid assuming financial and administrative responsibility for itinerants who chose the jungle over the mission.

Yet to see our Hobohemia as the result of societal design is to actively restrain and interpretively displace the “sensuous human activity, [the] practice” that made these jungles, especially those within Vancouver’s city limits. All but one of these settlements were forged in a situation of need, after “society” had denied thousands of transient men access to municipal relief programs, both public and private; the exception, we shall see, developed a more contradictory relationship with authorities. In claiming these spaces during the summer of 1931, homeless men of many races, ethnicities, birthplaces, and histories “designed” themselves their own heterotopias right in the heart of downtown Vancouver, islands of dispossessed collectivity amidst the stormy seas of possessive individualism that forced public recognition of the generalized spread of homelessness. This, surely, should not be considered any part of the official design for urban living in Canada.

The first of Foucault’s theses about heterotopias to consider is his division of these places into two forms: crisis heterotopias — “sacred or forbidden places” where we can find those “in a state of crisis with respect to society and the human milieu in which they live” — and heterotopias of deviation — places housing those “whose behaviour is deviant with respect to the mean or the required norm.” While his comment that “in our society, where leisure activity is the rule, idleness forms a kind of deviation” suggests that hobo jungles belong to the latter category, it is more productive to propose that jungles drew strength from global dynamics of crisis that effectively undermined, if not eradicated, many key economic and political means and norms. The Canada of 1945 was simply unimaginable in Canada, 1930.

Rather than a clear division, I have instead found chaotic combinations and fragile unities. Foucault’s claim that while each heterotopia “has a precise and specific operation within the society,” this operation could change depending on the context (citing the cemetery as his example) aids our framing of Hobohemia, especially if we free our categories from an inhibiting functionalism. Hobo jungles had long existed. But in the early 1930s, after a decade in which the continental labour market for the itinerant shrank in comparison to that for urbanized semi- and unskilled factory positions in mass production, jungles enabled the relatively rapid and widespread transmission of the practices of power-knowledge that had previously sustained a much larger community. Most important for our purposes are Foucault’s suggestive categorizations of space and time in these emplacements. Most Depression-era Vancouverites would have agreed with (if not themselves offered) the characterization of the hobo jungle as “connected with temporal discontinuities. . . .The heterotopia begins to function fully when men are in a kind of absolute break with their traditional time.”

While we need not see the jungles as invoking an “absolute break” with rationalized time, there is little doubt that the regularities of time-work discipline, even broadly conceived, did not obtain in these encampments. Indeed, this had long been identified as a central effect of unemployment more generally: being outside the realms of work and leisure, and thus forced to endure an unproductive and uncompensated life, jobless paupers, it was thought, lost the very sense of unthinking daily routine that bound these men to societal norms. I have, in very tentative fashion, offered a few arguments as to how Hobohemia gave rise to alternate temporal rhythms and spatial dynamics.

Finally, Foucault’s argument that heterotopias are endowed with the “ability to juxtapose in a single real place several emplacements that are incompatible in themselves” has proven invaluable, pointing to the overlapping of distinct social processes that emerged in the provisional absence of the forces of capitalogic and governmentality. Foucault offers two lines of possible analysis of these juxtapositions: as “creating a space of illusion that denounces all real space, all real emplacements within which human life is partitioned off” or, as in the “heterotopia of compensation,” as “creating . . . a different real space as perfect, as meticulous, as well-arranged as ours is disorganized, badly arranged, and muddled.” In this regard, he cites Jesuit endeavours in South America as “marvellous, absolutely regulated colonies in which human perfection was effectively achieved.” While Hobohemia was neither of these things — neither the denunciation of reality nor the search for meticulous perfection was required of inhabitants, although they were hardly prohibited — it embodied the localization of incompatible, even contradictory, social forces nevertheless. In the broadest of terms, Hobohemia introduced a division into the existing social formation (or society, if you prefer), with the resulting ensemble of social practices crystallizing in time and space an “actually realized” dialectical opposition to liberal-democratic capitalism on Canada’s “Left Coast.”

Here, it is appropriate to turn to Marx’s all-too-brief commentary on the “realm of freedom,” published in the third volume of Capital:

The realm of freedom really begins only where labour determined by necessity and external expediency ends; it lies by its very nature beyond the sphere of material production proper. Just as the savage must wrestle with nature to satisfy his needs, to maintain and reproduce his life, so must civilized man, and he must do so in all forms of society and under all possible modes of production. This realm of natural necessity expands with his development, because his needs do too; but the productive forces to satisfy these expand at the same time. Freedom, in this sphere, can consist only in this, that socialized man, the associated producers, govern the human metabolism with nature in a rational way, bringing it under their collective control instead of being dominated by it as a blind power; accomplishing it with the least expenditure of energy and in conditions most worthy and appropriate for their human nature. But this always remains a realm of necessity. The true realm of freedom, the development of human powers as an end in itself, begins beyond it, though it can only flourish with this realm of necessity as its basis. The reduction of the working day is the basic prequisite.

There is considerable debate among Marxists and others as to whether the “realm of freedom” can exist under capitalism. Earlier in the same piece, Marx wrestled dialectically with how to map the act of grasping simultaneously how both the “material conditions” and the “social relations” of capitalism were considered both the “prerequisites” of capitalism and “produced and reproduced by it.” If we adopt the same dialectic in approaching the “material conditions” and “social relations” of jungle life, we can imagine such a realm to be realized in Hobohemia.

To the extent that jungles were diagnosed and treated as an alternative order in the discourses of politicians and bureaucrats, in mass media publications, and in the very practices of public and private relief provision, they became an “Other” in civilizational terms, possessing an entire way of life, including a language all their own. Yet Hobohemia itself — the idea of the jungles as a non-contiguous homeland attached to but still outside of capitalogic and governmentality — exists only because, in this clearly delimited context, an alternative order did emerge. It was characterized by new configurations of time and space and a new mode of acquisition that defied possessive individualism.

The social practices with which hundreds of thousands of mobile men collectively seized space and secured sufficient food, shelter, and other resources in order to make it to the following day, and the effects of the mass adoption of this mode of acquisition, ran directly counter to the laws of capitalogic. At the same time, the builders of bc’s hobo jungles obviously remained partially dependent upon capitalism to meet the daily demands of the realm of necessity, and it is not ironic but tragic that this realm of freedom took root in the soil of continuing exploitation. These jungles were not embedded in what Marx (and probably every other Marxist, anarchist, socialist, and so on) imagined as new-found freedoms in the realm of necessity but rather in a range of practices that parasitically drew value from the working world, which jungle inhabitants visited from time to time, in order to redistribute that value in a collective, non-exploitive fashion. Moreover, these social relations emerged without much in the way of the institutional supports and social sanctions central to the primitive accumulation of capital, and the scarcity of entitlements certainly limited what could be done in a generally hostile context.

As a homeland, then, Hobohemia had its distinct limits. Unable to sustain itself with production (autonomously organized or not), Hobohemia could only exist within a wider social formation that generated wealth sufficient to allow for its (often unlawful) redistribution by those at the bottom of the food chain, if they were not part of another chain altogether.

There remains one key element to be fleshed out. To fully understand how Hobohemia offered an alternative to capitalogic and governmentality, we need to grapple with its existence as a homeland without a state — or, in simple terms, as a non-state space. In this regard, I have found most useful James Scott’s anarchist history of the Zomia region of southeast Asia, The Art of Not Being Governed, which offers an analytical framework for bringing into view those who have evaded or resisted state-making projects for centuries. Because Scott’s argument is predicated upon the various agricultural and spatial possibilities afforded by the largely rural context that he examines, it cannot easily be transferred to the ever-rationalizing twentieth-century North American city. Nonetheless, as Scott observes, “Civilizational discourses never entertain the possibility of people voluntarily going over to the barbarians,” and this is largely true for Canadian historiography.

The mobile residents of Hobohemia, whether consciously or not, left behind the liberal order and entered a space in which the rule of law and the free market rarely obtained. Just as important, the jungles also lacked the “material conditions” and “social relations” — to borrow Marx’s language — central to the modern state’s existence, let alone to its successful functioning. One could not make a state in Hobohemia, regardless of intent or ability, because social relations therein gave governmental projects little to latch onto to create a basis for one’s claims of continuous authority in these places. Indeed, one could not even stop one’s newly declared subjects from moving on to the next jungle. To rule over and thus regulate jungle life, there was but one option, and that was to eradicate each encampment until nothing remained but civilization, where no person would ever be compelled to inhabit a muddy trench or toil on an assembly line owing to forces beyond his or her control.”

- Todd McCallum, Hobohemia and the Crucifixion Machine: Rival images of a new world in 1930s Vancouver. Edmonton: Athabaska Univesity Press, 2014. pp. 108-114..

#vancouver#canadian history#hoboes#hobo jungle#heterotopias#hobohemia#shantytowns#transients#single unemployed men#poverty knowledge#anti-capitalism#theory#empire of theory#karl marx#michel foucault#capitalism in canada#capitalism in crisis#academic research#research quote#hobohemia and the crucifixion machine

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Borges' Animals

In "The Analytical Language of John Wilkins," Borges describes 'a certain Chinese Encyclopedia,' the Celestial Emporium of Benevolent Knowledge, in which it is written that animals are divided into:

those that belong to the Emperor,

embalmed ones,

those that are trained,

suckling pigs,

mermaids,

fabulous ones,

stray dogs,

those included in the present classification,

those that tremble as if they were mad,

innumerable ones,

those drawn with a very fine camelhair brush,

others,

those that have just broken a flower vase,

those that from a long way off look like flies.

This classification has been used by many writers. It "shattered all the familiar landmarks of his thought" for Michel Foucault. Anthropologists and ethnographers, German teachers, postmodern feminists, Australian museum curators, and artists quote it. The list of people influenced by the list has the same heterogeneous character as the list itself

https://multicians.org/thvv/borges-animals.html

1 note

·

View note

Text

"I am going to get a good grade in ___________, a thing that is both normal to want and possible to achieve" drifts through my brain with positively alarming regularity.

#this is because I managed to have an interesting conversation with my uncles at dinner#and also I had Work Stuff to do in front of my mother and felt so so proud of myself#sometimes being human is very ridiculous.#celestial emporium of benevolent knowledge

7K notes

·

View notes

Text

In "The Analytical Language of John Wilkins," Borges describes 'a certain Chinese Encyclopedia,' the Celestial Emporium of Benevolent Knowledge, in which it is written that animals are divided into:

those that belong to the Emperor,

embalmed ones,

those that are trained,

suckling pigs,

mermaids,

fabulous ones,

stray dogs,

those included in the present classification,

those that tremble as if they were mad,

innumerable ones,

those drawn with a very fine camelhair brush,

others,

those that have just broken a flower vase,

those that from a long way off look like flies.

#borges#jorge luis borges#animals#emporium#celestial emporium of benevolent knowledge#the analytical language of john wilkins#list#taxonomy#classification

0 notes

Note

whats that quote you always parody thats like "good kings, bad kings, kings who shake as if theyre mad" from?

it's from the Celestial Emporium of Benevolent Knowledge:

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

wheres that post thats like 'whats the worst thing youve read for school' bc the analytical language of john wilkins is definitely... giving me grief

#celestial emporium of benevolent knowledge is very.... nighjm.. i might just be that im stupid but like#mbbbaf

2 notes

·

View notes