#bobby beausoleil photos

Text

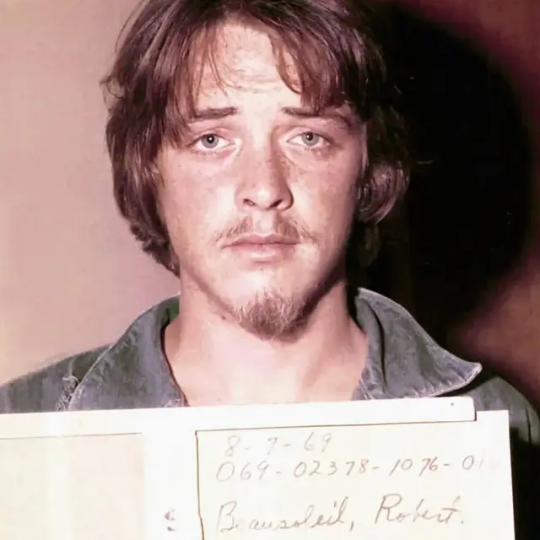

Bobby Beausoleil booking photo 8/7/69

#Bobby Beausoleil#mugshot#1969#vintage photography#manson family#vintage los angeles#vintage california#history#true crime#gary hinman#the beginning of the end#cupid

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

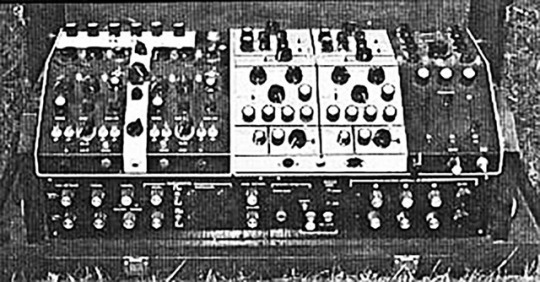

Bobby BeauSoleil's Dream Machine Amp

78 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Favorite Books: Sway by Zachary Lazar

#Sway#Zachary Lazar#novel#photo set#compilation#biographical fiction#the 1960s#Rolling Stones#Mick Jagger#Brian Jones#Keith Richards#Anita Pallenberg#Kenneth Anger#Bobby Beausoleil#I just have a lot of feelings

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

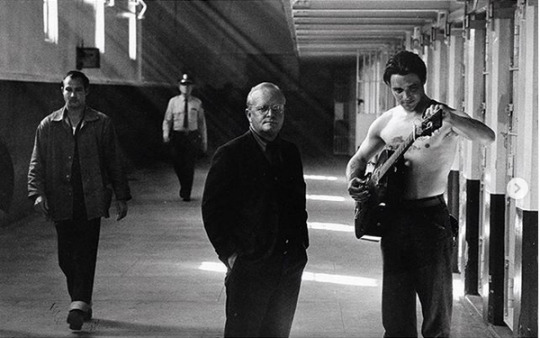

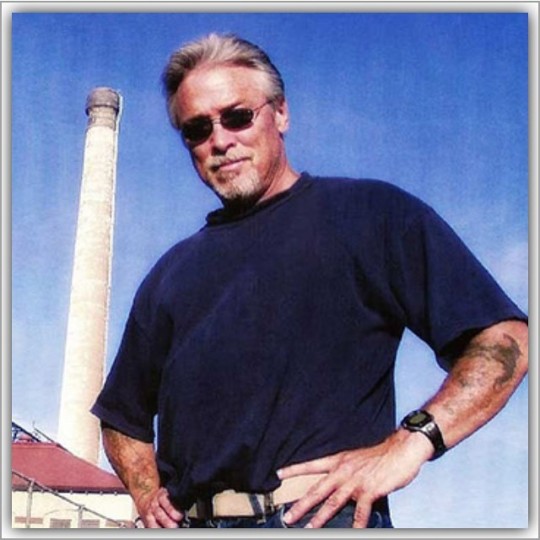

BOBBY BEAUSOLEIL

Bobby Beausoleil et Truman Capote, prison de Saint Quentin, 1972

Photo: Peter Beard

#bobbybeausoleil#trumancapote#peterbeard#peter beard#truman capote#Bobby Beausoleil & Autres anges cruels

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Man Who Murdered the Sixties

It’s been a half-century since Charles Manson and his loopy minions conspired to commit a series of murders that still fascinate and flabbergast the world.

Manson, who died in prison in 2017, would savor the attention he continues to attract, including in this summer’s Quentin Tarantino film (“Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood”) and several new books, including my own.

In March 1967, at age 32, Manson was a fresh federal parolee who stumbled into San Francisco as American ingenues in peasant dresses and bellbottoms—runaways, hitchhikers, and lost souls—were streaming in for the Summer of Love. His timing was impeccable. The patchouli-scented sexual revolution created a perfect petri dish for his predation.

Using prison-honed talents as a con man and middling skills as a guitarist and singer-songwriter, Manson soon began building a cult of as many as 35 young hippies, three-quarters of them women.

He would spin campfire lectures for his stoner clan featuring Psych 101 dogma about projection and reflection. He basted their brains in a mix of Jesus Freakiness, Dale Carnegie hucksterisms, Norman Vincent Peale’s sunny-sided platitudes (“You are perfect!”), and the buggy self-help triangulations and “dynamics” of his prison-library Scientology.

Charles Manson. courtesy Oxygen

They believed he was a godly mystic.

The writer David Dalton nailed Manson in eight words: “if Christ came back as a con man.” Joe Mozingo of The Los Angeles Times said, “He was a scab mite who bit at the perfect time and place.”

Using the playbook of pimps and cult patriarchs, he isolated troubled young women from their past lives and controlled their bodies and minds. He was the Wizard of Oz for libertines, and he as much as told them so.

Susan Atkins, who became one of Manson’s most prolific killers, said Manson often mocked his own followers’ blind faith.’

“He said, ‘I have tricked you into doing what I want you to…It’s like I’ve got a bunch of slaves around me,” she told a grand jury in December 1969, after her arrest.

The Enigma of Charles Manson

Manson was an enigma on many levels.

The “Manson Women” Photo courtesy Oxygen

He was a racist and sexist imbued with the old-timey sensibilities of an Appalachian upbringing. He preached female subservience and racial segregation, and his young followers lapped it up in the midst of a flowering civil rights movement and on the cusp of modern women’s liberation.

Many were willing to kill for nothing more than Manson’s validation.

“You can convince anybody of anything if you just push it at them all of the time,” Manson once said, “…especially if they have no other information to draw their opinions from.”

Just 29 months after Manson began assembling his naifs into a communal Family, these “heartless, bloodthirsty robots…sent out from the fires of hell,” as a prosecutor would describe them, carried out a series of proving-ground murders in Los Angeles over four weeks in the summer of ‘69 that still has a place of prominence in America’s storied pantheon of crime spectacles.

The primary motive was money to allow the Family to finance a retreat to California’s Death Valley to ride out the race war that Manson predicted was coming.

The first victim, the Family’s good friend Gary Hinman, was Killed on July 27. Two weeks later, on Aug. 9 and 10, Manson followers killed the pregnant actress Sharon Tate, coffee heiress Abigail Folger, Leno and Rosemary LaBianca, and five others in acts of casual savagery that remain a peerless mashup of celebrity, sex, cult groupthink, and bloodlust.

Police outside 10050 Cielo Drive in Hollywood where the blood-splattered bodies of Sharon Tate and her four friends were found. Photo by George via Flickr

“It had to be done,” one of the killers, Leslie Van Houten, explained after her arrest. “For the whole world’s karma to be completed, we had to do this.”

Writer Dalton, who covered Manson for Rolling Stone, called him “the perfect storm” for 1969.

“It was the conflation of mystical thinking, radical politics, drugs, and all these runaway kids fused together,” Dalton told me.

“The world seemed to be in death spiral of violence, and we thought the whole hippie riot was about to begin to save use all. We were going to take over and everything would be cool. In fact, the opposite was happening, embodied by Charlie Manson.”

The implausible Manson story cannot be separated from the context of its era, as some Americans were asking essential questions about what their country ought to be.

The half-decade of 1965 to 1970 saw ghetto riots, the emergence of a vibrant new psychedelic culture, shocking political murders, riveting space exploration, escalation of the war in Vietnam, and burgeoning protests of the same.

Two months alone in the summer of 1969 brought an extraordinary series of events. On June 28, a police morals-squad raid on the Stonewall Inn, a gay bar in New York’s Greenwich Village, touched off three days of rioting—and ignited the gay rights movement. On July 18, Ted Kennedy, surviving male heir to the American political tragi-dynasty, fled the scene of a fatal car wreck on Chappaquiddick Island, Mass. On July 20, the world watched on TV as Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin took their stiff, bouncing strolls through moondust.

Among the viewers was a small group of friends and kin gathered at the home of Sharon Tate. Twenty days later, on Aug. 9—50 years ago today—four members of the same group would be savagely murdered by Manson’s second kill team. A week after that, more than 400,000 peopled endured organizational bedlam to attend the Woodstock Festival, 100 miles north of New York City. That same weekend, Hurricane Camille pounded ashore on the Gulf Coast, east of New Orleans at Pass Christian, Miss., killing 256 people.

The Sixties created Manson, and his crimes were an exclamation point to a turbulent decade.

A ‘Child of the ‘30s’

But as he liked to say, “I am a child of the ’30s, not the ’60s.”

He was born to a prostitute mother and drive-by father in 1934 and raised by relatives in Kentucky, Ohio and West Virginia coal country. He became a chronic juvenile delinquent who flailed his way through a Dickensian childhood. A tiny boy who grew into an elfin but sinewy man, he was locked up in reform school, jail or prison for all but a few years of his life from age 13 to the grave.

He spoke or wrote a million words about his life and crimes—in court, in letters, in media interviews. He bleated many excuses for his wasted life, almost always beginning with a lack of parenting and proper education.

Manson often played crazy, but that was a studied tactic. As Vincent Bugliosi, his prosecutor and biographer, told Time magazine before he died in 2015.

“His moral values were completely twisted and warped, but let’s not confuse that with insanity. He was crazy in the way that Hitler was crazy…So he’s not crazy. He’s an evil, sophisticated con man.”

Manson preached a homespun version of liberation theology—the freedom to be you. But a switch was flipped in the fall of 1968, when the Beatles released their White Album.

Manson convinced his followers that the world’s most famous band was sending him direct messages in the lyrics, including those of “Helter Skelter.” He imagined that Paul McCartney’s song presaged a race war that would induce the Family to retreat to a desert hideout, then emerge heroically and install Manson as a world leader and master breeder.

Manson recast his horny young stoners into a classic apocalyptic cult, prepping for end times. Growing impatient for the race war, Manson decided to “show blackie how to do it” by committing a series of murders and leaving clues meant to implicate the Black Panthers, that era’s subject of America’s ever-changing moral panic.

The starry-eyed plan was a failure on every level.

Before Manson “got on his “Helter Skelter” trip,” according to Paul Watkins, another follower, “it was all about fucking.”

Five former members of the Family, all senior citizens now, are still imprisoned, 50 years along: Leslie Van Houten, Patricia Krenwinkel, Charles Watson, Bobby Beausoleil and Bruce Davis.

Manson follower Lynette “Squeaky” Fromme was imprisoned for the attempted assassination of President Gerald Ford. Photo via YouTube

Many others have died, including Watkins and Susan Atkins.

Most renounced Manson long ago, although Lynette (Squeaky) Fromme, an early acolyte who served 34 years in prison for a 1975 assassination attempt on President Gerald Ford, self-published an autobiography last year that was largely dedicated to minimizing Manson’s culpability.

Atkins, who once seemed to enjoy her public profile as an illustrious sexpot murderess, had a personal reckoning before her death from brain cancer in 2009.

“In hindsight,” Atkins wrote in her memoir, “I’ve come to believe the most prominent character trait Charles Manson displays is that of a manipulator. Not a guru, not a metaphysic, not a philosopher, not an environmentalist, not a sociologist or social activist, and not even a murderer.

David Krajicek

“His long-term behavior is one predominantly of a practiced manipulator.”

She called him “a liar, a con artist, a physical abuser of women and children, a psychological and emotional abuser of human beings, a thief, a dope pusher, a kidnaper, a child stealer, a pimp, a rapist, and a child molester. I can attest to all of these things with my own eyes.

“And he was all of these things before he was a murderer.”

This essay is adapted from David J. Krajicek’s new book, Charles Manson: The Man Behind the Murders that Shook Hollywood (Arcturus).

The Man Who Murdered the Sixties syndicated from https://immigrationattorneyto.wordpress.com/

0 notes

Text

Visiting the Westerfeld House and Its Haunted Past.

When I mention the Westerfeld house to people they generally have never heard of it. The house itself is located on the corner of Fulton Street and Scott Street in San Francisco, California. I hadn't heard of it until a random purchase I made a couple years back at a Goodwill in Dallas. So, how did a house halfway around the United States peek my interest and a ton of others online? Here's the story.

How I Learned of the Westerfeld House

As I've mentioned in other posts, I love thrifting. I'm sure that either makes me a 90 year old grandma or a hipster from Austin, Tx. Regardless, a thrifting trip I had with my friend James mid-skateboarding sesh ended with me and a picture of a strange, spooky-looking house.

I'm not sure why, but when I saw this buried among a pile of random picture frames and old, reprinted landscape photos at the Goodwill, it grabbed my attention and wouldn't let go. I purchased it for somewhere around $3.99. I immediately googled the address and the artist's name. Sadly, I've still never been able to make out the artist's name, but I did find a famous home on those cross streets. The Westerfeld House was filled with a rich history I could have never guessed by just looking at the old, Victorian-styled home.

The Westerfeld's Wild and Haunted Past

The Westerfeld house was built in the late 1800's by builder Henry Geilfuss on behalf of the home's owner, William Westerfeld. William died in 1895 and the structure was sold to a contractor by the name of Jonathan J. Mahoney who loved to entertain celebrities as guests, (who wouldn't?). The list includes radio pioneer Guglielmo Marconi who reportedly used one of the top rooms to transmit the very first radio signals on the west coast and the famous Harry Houdini, who experimented in the same room by attempting to send telepathic messages to his wife across the Bay.

Fast forward to 1928 when the house was bought again by Czarist Russians who turned the place into a nightclub called Dark Eyes while making the upper floors meting rooms. It was renamed as the "Russian Embassy".

In 1948, the night club had shut down and the house became a 14-unit apartment building that was rented to African-American Jazz Musicians, including John Handy.

By the 1960's, the house had all sorts of residents inhabiting its rooms. One of the most interesting occupants (IMO) was occult filmmaker Kenneth Anger. Because of Kenneth's dark body of work, his visitors lent themselves toward a more sinister nature. This included the famed criminal/cult leader, Charles Manson, as well as Bobby Beausoleil who later joined Manson's cult and was involved in the first Helter Skelter murders.

Kenneth would often film his projects in the Westerfeld house where he had carved a giant pentagram into the wood of the top floor. Anger and his friends would also hold satanic rituals in the ballroom. This attracted another famous visitor, Anton Zandor LaVey, who founded the Church of Satan and wrote The Satanic Bible. At one point, they had removed the ceiling in order to create a medium for their dark energies, as well as look for UFOs. In fact, many unidentified spacecrafts were claimed to have been seen from the top of the westerfeld, but I'm guessing the amount of drug use probably assisted these sightings.

Here are two of Anger's films. (Be warned: there's nudity, so probably not a great film for your kids to watch.)

Many more notable characters passed through the hallways of this house while it served as apartments. This included: Mick Jagger, Jerry Garcia, Chet Helms, James Gurley, Janis Joplin, Fayette Hauser, Tom Wolfe, Jimmy Lovelace, Heidi McGurrin, Art Lewis, and Ken Kesey. You can see the full list HERE.

In 1969, two men purchased the home for $45,000 and began remodeling random sections of the house until it was purchased again in 1986.

"Jim Siegel purchased the home and has since retrofitted the foundation, removed the dropped ceilings, re-wired, re-roofed, and re-plumbed, and restored the interior and exterior woodwork and the historic, ground-floor ballroom, and decorated the 25-foot ceiling with period wallpaper crafted by Bradbury & Bradbury." -- Wikipedia

The Westerfeld is still owned by Jimmy Siegal to this day and is maintained exquisitely. Photo collection below from Photographer Patricia Chang via sf.curbed.com.

My Visit to the Westerfeld House

Almost two years after I found the drawing in a Dallas Goodwill, My girlfriend (now fiancee) and I traveled to Sequoia National Forest and then to San Fran where after a lot of walking up and down the insane, but beautiful hills that make up the Castro neighborhood, we came upon the house I'd been dreaming of seeing. The Westerfeld looked like it belongs on r/evilbuildings.

As I stood in the park across the street from it, I felt this wonderful sensation of the house's presence. It was dark, brooding and fantastic all at the same time. One could feel the history emanating from the property. With the famous painted ladies on one side of the park, the Westerfeld stood out as a Victorian structure from another time and vision.

I'm not sure a house (other than the one I grew up in) has ever left such an impression on me like the Westerfeld has. I love this house. The architecture; the city it sits in; the history; it all blends to create one of my favorite places and I've never even been inside. One day I'd love to walk through this historic home, but until then, my visit to the exterior will have to suffice.

Below are some other angles I captured when I visited.

If this post was of any interest to you, you may check out the film currently being made about the Westerfeld House called House of Legends. You can find more information and even donate to the project HERE. Thanks for reading!

0 notes

Link

TOWARD THE END of his densely packed and star-studded survey Everybody Had an Ocean: Music and Mayhem in 1960s Los Angeles, William McKeen offers an apocryphal exchange between music producer Terry Melcher and an aspiring local singer-songwriter named Charles Manson: “Charlie, there’s mixed emotions about promoting you,” Melcher (who was Doris Day’s son) is said to have told him. “You’re unpredictable. You amaze me at times, and at other times, you disappoint the hell out of me.” If only it had ended there.

Manson was already a known (though “unsigned”) commodity to some of the most highly successful rock musicians in the L.A. area at the time. In late 1968, Beach Boys drummer Dennis Wilson was telling the music press about a mystery man in Los Angeles whom he called “the Wizard,” a spiritual teacher and wise man, his personal guru. The Wizard was named Charlie, Dennis said. He had “recently come out of jail after 12 years.”

“He’s dumb, in some ways,” Wilson informed the British music paper Record Mirror, “but I accept his approach and have learn[ed] from him. […] His mother was a hooker, his father was a gangster, he’d drifted into crime but,” (but?) “when I met him I found he had great musical ideas.” Wilson hinted that he was thinking of launching the singing Manson girls as a group, the “Family Gems.” (Imagine that: Frank Zappa and the GTOs, I’d like you to meet Dennis and Charlie’s Family Gems.)

As McKeen tells it, Dennis was an eager champion of his friend Charlie, encouraging his songwriting, co-writing songs with him, and helping him make contacts to advance his musical career. Even Dennis’s brother Brian, McKeen writes, “understood why Dennis was so fascinated by Manson,” but ultimately found him “creepy” and locked himself in the bedroom whenever Charlie (often barefooted, unwashed, and reeking) was in the house.

This book’s subtitle is, of course, a dead (Manson) giveaway, and a glowering photo of Charles-the-demonic-fifth-Beatle graces the cover just to drive the point home. McKeen’s narrative doesn’t skimp on the promised Manson lore, either. Few things seem as out-of-joint and fascinating as the chancy, fateful encounters between high accomplishment and degradation, hence the undiminished appetite for details of the bizarre and fraught relationship between the Beach Boys and Dennis Wilson’s dreadful choice of a guru and creative partner, who would end up physically threatening him. Music + crime = sexy story: witness the Phil Spector shooting saga, which also makes an appearance in this book.

Within the most exalted circles of the L.A. music scene in the late ’60s, Manson was regarded as a talented up-and-comer, and, like many up-and-comers, very much on the make. These circles included top-tier artists like Mama Cass Elliot, Frank Zappa, and Neil Young, who not only acknowledged having played with Manson (!), but was gutsy enough to praise his songwriting and guitar-playing even after the Tate murders. (“Shakey” did dub Manson “spooky,” at least retrospectively. It’s too bad Young doesn’t divulge more of their interactions in his autobiography.)

The collaboration between Dennis Wilson and the Wizard did result in the one known Charles Manson song that was actually recorded and released on a Beach Boys record: “Cease to Exist,” Charlie’s original title, gave way to “Never Learn Not to Love,” the B-side of a single for the 1969 album 20/20. It’s a pretty good song, though Manson’s version is better (you can hear it on the famous Charles Manson album Lie). There are widely credited rumors that Brian and/or Dennis Wilson helped Charlie to record an entire album’s worth of music at Brian’s home studio, but brother Dennis, so the story goes, torched the tapes not long afterward with the comment, “this should never be on the Earth.” (The rumor doesn’t really specify whether Wilson burned the creepy recordings before or after the crimes, though.)

“In ’67? He was a sweet-faced little pixie!” a former Laurel Canyon denizen, who worked at the famous Canyon Store, once told this writer about Charlie. “When I saw him again in ’69? Whoah…” The wiry little minstrel from Griffith Park with the twinkle in his eye and the empathic concern toward young runaway hippie girls had transmogrified into a pissed-off, ferocious, bloodletting monster.

Though presented as a more or less comprehensive summa of the milieu Manson haunted, the book is clearly written by a Beach Boys fan, so let the buyer beware. In fact, let’s go to the index, and to the last entry: no, it appears McKeen has no interest (zero) in lifelong Laurel Canyon resident Frank Zappa, at the time a major musical arbiter and the begetter of many a band who (love him or loathe him) now serves as a dependable touchstone of the Laurel Canyon scene in most of the accounts I’ve come across; see Harvey Kubernik, Barney Hoskyns, and others.

McKeen’s musical blind spot also means this book has nothing to say about Arthur Lee and Love, a prime dark-side-of-psychedelia band, now with a huge posthumous reputation. One would think that the group’s one-handshake-away proximity to Manson would serve as a perfect entry into the crime-and-music nexus this book is ostensibly about; it is on record that Manson lieutenant Bobby Beausoleil, a talented guitarist and songwriter, often sat in with Love and was a good friend of Johnny Echols, the group’s bass player. Biracial Arthur Lee was himself as tortured as they come, eventually serving time for threatening a neighbor with a gun, but he was neither a psycho nor a killer.

McKeen has fun dipping into the purported origin stories of rock: “The Moondog Coronation Ball at Cleveland Arena on March 21, 1952, was the first rock n’ roll concert”? Really? “A little bit of the genetic material from that show,” he writes, “can be found any place where guitar, bass, drums and fans gather. That concert featured an all-star bill…” (McKeen then names three proto-rock combos whose names are now forgotten.) The man responsible for the gig was good old Alan Freed, the legendary Cleveland-based disc jockey who didn’t create the phrase rock-and-roll but was the first to make it popular. As McKeen tells it, a chance comment made to Freed in 1952 by a rhythm-and-blues musician named Billy Ward that he was about to “go rock and roll,” i.e., have sex, inspired Freed to give “this music he loved” the new moniker (though if I may enjoy my own moment of pedantry here, let it be noted that some recorded blues lyrics from the 1920s include the word “rock,” with the same sexual connotation).

This digging-for-origins stuff is, of course, a popular sport, but McKeen misses many more relevant (counter)cultural precedents. For instance, he leaves out (that aversion to Zappa again?) the story of a small group of post-beatnik bohemians in Los Angeles, including Zappa, who congregated at Canter’s Deli on Fairfax in the early ’60s and dressed in colorfully mismatched thrift-store clothes, arguably launching the psychedelic era, or at least its look. This group called themselves “freaks.” They made their mark and got the hippie look going, but for some reason the label didn’t last.

But what McKeen does include is interesting and provocative. He takes the warts-above-all approach in depicting the stars, like David Crosby (“David Van Cortlandt Crosby had all the arrogance that went with his stuffy name”), and takes a few digs at “bloated” and booze-addled Jim Morrison. Such low-down, contrarian treatment of so-called legends is refreshing, I must say, as is his surprising put-down of ’60s youth in general: “[P]erhaps the first generation to consider itself relevant without earning its place at the table.”

McKeen’s hero is clearly the tragic musical genius and obsessive perfectionist Brian Wilson. This is made plain by his closing benediction: “Though Brian Wilson and Mike Love no longer collaborate and Carl and Dennis Wilson are gone, they are all still together on the radio late at night, where they join voices and are young and golden and beautiful forever.”

If you’re looking for crime stories other than Manson, you’ll need to slog through enough Laurel Canyon rock-bios to get to the compelling tale of Frank Sinatra Jr.’s weird kidnapping in 1963 (give credit to Junior, who reportedly told his captors, “you guys don’t scare me”) and the strange connection between that crime and the hugely successful singing duo Jan and Dean (I won’t give it away here, just buy the book). Ultimately, like most mash-ups of musical and criminal lore, McKeen’s book makes for good reading, though it doesn’t cover either subject exhaustively.

¤

Anthony Mostrom, a former Los Angeles Times columnist, is currently a book reviewer and travel writer for the L.A. Weekly.

The post Wiry Minstrels and Bloodletting Monster: William McKeen’s “Everybody Had an Ocean: Music and Mayhem in 1960s Los Angeles” appeared first on Los Angeles Review of Books.

from Los Angeles Review of Books http://ift.tt/2gTG9VC

via IFTTT

0 notes

Photo

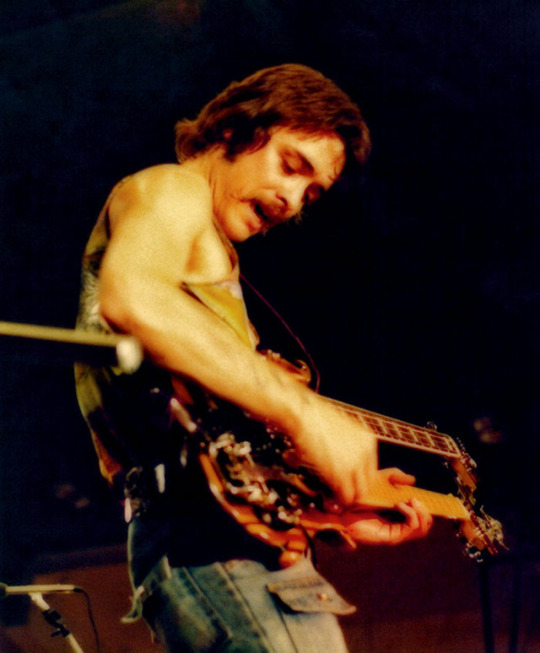

Bobby Beausoleil part 4 He continues to create music from prison and several albums have been released. Among them was The Lucifer Rising Suite, an anthology which documents the entire Lucifer Rising soundtrack project from its earliest beginnings in 1967 to its ultimate completion and delivery to the filmmaker in 1979. In addition to the actual soundtrack, alternate themes, musical and soundscape experiments, and some live performances are contained in the box set. In 2005, a selection of his was artwork exhibited in Clair Obscur Gallery, Los Angeles. Just before the exhibition, the gallery exhibited photos of Sharon Tate. The parole board, in denying his parole in 2005, stated that this display and marketing of Beausoleil's artwork was exploitative of the victims and showed a lapse of judgment by Beausoleil. To date, all of his bids for parole have subsequently been denied. #destroytheday

0 notes

Photo

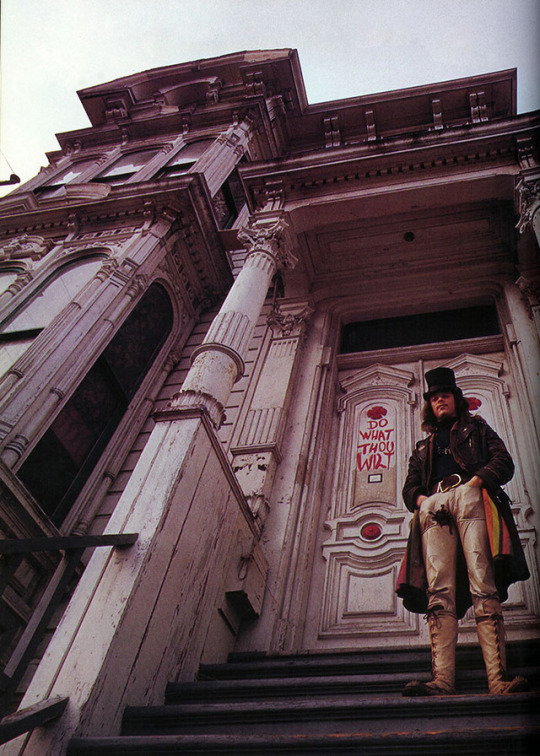

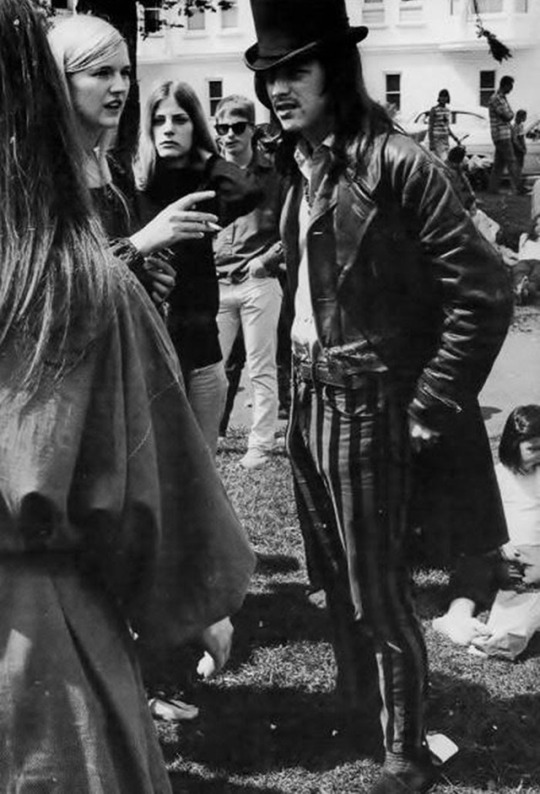

Bobby BeauSoleil with the Magick Powerhouse of Oz in the Westerfeld House.

26 notes

·

View notes

Photo

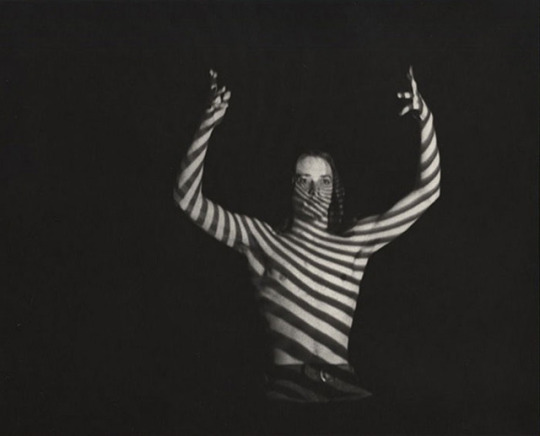

Bobby BeauSoleil Behind the Scenes in Kenneth Anger’s Invocation of My Demon Brother.

#bobby beausoleil#robert beausoleil#Kenneth Anger#invocation of my demon brother#bobby beausoleil photos#bobby beausoleil photo

27 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Bobby BeauSoleil at the Westerfeld House in 1967 (photo by Don Synder).

19 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Bobby BeauSoleil Behind the Scenes in Kenneth Anger’s Invocation of My Demon Brother.

#bobby beausoleil#robert beausoleil#Kenneth Anger#invocation of my demon brother#bobby beausoleil photos#bobby beausoleil photo

10 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Bobby BeauSoleil playing Lucifer Rising with the Freedom Orchestra.

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Bobby BeauSoleil with Doubleneck at Tracy Prison (1970s).

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Bobby BeauSoleil (photo by Gene Anthony).

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

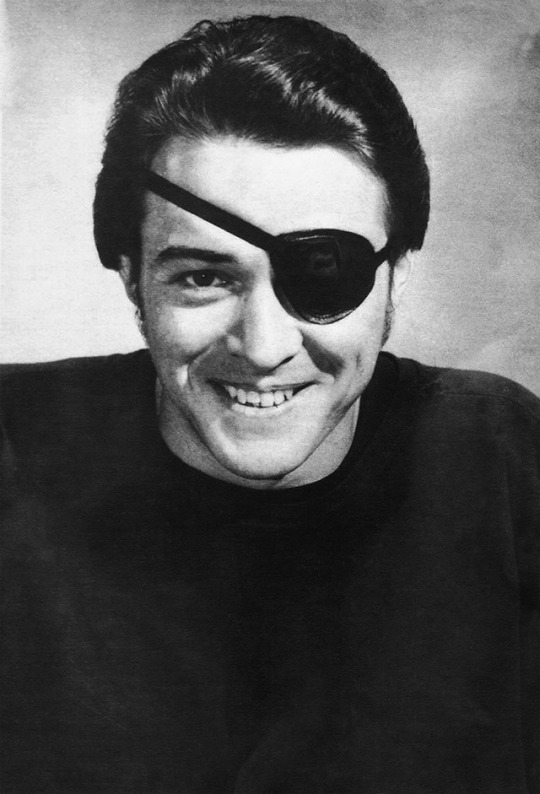

Bobby BeauSoleil with eyepatch in 1973.

6 notes

·

View notes