#and he was already very dubious in his original run especially in regards to race and i am SCARED of him penning the first black doctor

Text

the more i think about the 60th specials the angrier and more despondent i get. i actually wish rtd had never come back get him out of here

#seeing old stuff of eccleston vaguely talking shit on rtd and his cronies.. thinking about how badly written the specials were#not just in a storytelling sense but also politically. he somehow got so much worse#and he was already very dubious in his original run especially in regards to race and i am SCARED of him penning the first black doctor#uh. i just wish theyd gotten someone new who wasnt a piece of shit.#idk im just so nervous lol rtds writing has taken a nosedive into being absolute crap where he drops in little cancel culture lines#and shit like that and nonsense dictator of the planet doctor moments to quickly wrap up a problem and no critical analysis#of anything thats going on ever. its actually horrific#im sooooo so fucking nervous for s14 lol#peter capaldi save me (i need to rewatch 12 to feel better)#txt

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

ABBAS KIAROSTAMI’S THE WIND WILL CARRY US “You’ll get used to it if you stay…”

© 2017 by James Clark

You might be tempted, by its glowing foothills landscape caressed by blue-chip film stock (Kiarostami’s farewell to 35 mm ancient film—henceforth to be a video guy) and patently dull city slickers impinging upon the self-evident graces of rural ways, to assume that our helmsman has, with his 1999 outing, The Wind Will Carry Us, relented from the rigorous nuances of a triumph, like Close-Up (1990). But that would be a loss of faith that the mutual exchange of sophisticated treasure between him and Jim Jarmusch does not exist.

Evidence that such a nexus does exist is in fact abundant in our puzzling film today. Behzad, a filmmaker being part of a team of “reality TV” journalists biding their time in an Iranian mountain village until they go live to cover the death of a slowly declining 100-year-old woman and the region’s eccentric funeral rites, has no taste for the various domestic and wild animals to be encountered, especially while frantically driving to hilltops whereby to discuss, with optimal phone reception, the wasted time with the producer back in Tehran. (That latter motif could be called Dead Woman; and the unforthcomingness all round could be called Shades of Jarmusch. The volatility of that phenomenon of dead while alive speaks to the hard work Jarmusch and Kiarostami share.) It was one thing to be bored by the various media underlings in the entertainment food chain. It was, however, serious ca-ca to, one day at the, frustrating enough, reporting heights, overturn a large tortoise and leave him struggling. Therewith, the kind of logical retributional earthquake, leaving offenders instantly Dead Men in the eyes of Jarmusch, applies heat in such a way as to suggest to the wary that extreme tests, at Close-Up levels, are at center-stage. (Behzad, in American-dude-jeans and untucked shirt, struts in dead man mode amongst his regular few contacts and irregular many presumed primitives with Alpha staging, recalling very well, Willie, the show-off Hungarian immigrant to Lower Manhattan, in Stranger than Paradise and also, Jack, the pimp, in Down by Law (both roles played by deadpan hipster musician, John Lurie). (That attitude being covered by the Jarmusch keyword, “jerking off.”)

In addition to that hipster-manqué presence, there is a nifty opening scene where the documentary crew in their Land Rover pass through arresting scenery which fails to arrest them. As with the airhead magazine sensationalist in Close-Up, the conversation—perched upon those exquisite chromatics, textures and compositions and, as seen from a distance, the kinetic frisson along the twisting, dusty roads—is directly vapid but indirectly biting. “Where’s the tunnel, then…”/ “We passed it…”/ “Oh, someone’s been sleeping… We’re headed nowhere… If anyone asks, say we’re looking for buried treasure…” Finally reaching the destination (and deciding to pose as telecommunications engineers), their car stalls. In Jarmusch’s Night on Earth, five taxi drivers and their passengers around the world don’t exactly experience car trouble; but in one instance a driver fakes not being able to drive without halting shakes, and there is another episode where an elderly passenger dies in the back seat of a wisecracking Roman cabby. And, in every instance, those rides kick up a formidable amount of self-incrimination.

At breakfast the next day, Behzad offers his cronies some apples he’s found amidst the fertile terrain juxtaposed with the rocky cliff on and in which the settlement was constructed. (Its fertility also comprises a pliable local agent [a relative of one of their colleagues not directly involved in the expose].) They can’t be bothered getting up that early; but action does occur in the form of one fruit rolling off a table on the porch/ dining area and scooting down the facades of the ancient structures built into a wall of stoneface. It reaches a road and rolls smoothly down-hill, a picture of old-time inertia and a picture of new-time rippling as coinciding with the empty aerosol can sent on its way on a hilly Tehran street by the taxi driver in Close-Up. The extra feature in this latter film is the projectile’s being an earthy and delicious phenomenon. It seems (to some) to suggest that unlike the scheming, mechanically inclined menfolk, there are the women of this turf, bringing the saga to apposite heights of harmony and affection. Critic, Jonathan Rosenbaum, has maintained that the core of Kiarostami’s art has to do with his acuity about that “esoteric” practise which includes attention to a supposed rich, widespread though hidden sensuality effectively sustained by the domesticity of the vast majority of Iranian women. As if to anticipate jumping to such facile good news, our would-be modernist/ millennial protagonist gets close-up to the female owner/ operator of a café. His thin veneer of edginess (so close here to Willie) brakes down and he tells her it is disorienting to see a woman doing what she does. The proprietress contends that he must have seen his mother serving tea at home (not so strong an argument inasmuch as Behzad was upset by the public activity and its being an affront to male dominance). “It’s my café, my territory,” she challenges, adding that women accomplish many tasks—an important one being their “night work.” But that inventory of advantage would hardly be the mystical trump to transform a desert into an oasis. Later we see her frozen in hate and depression regarding a relationship with a man who drives a yellow motorcycle. (Hossein, the lost movie geek in Close-Up, is counselled not to try to make an impression with a bouquet of yellow flowers.) Her imprecation as he drives off— “You’re a coward if you come back!”—dashes the fantasy of graceful femininity being the real driver of world history. She certainly routs the stranger. But in the course of doing so her stolid, prosaic energy speaks against the truly high stakes which Mrs. Ahankhah, in Close-Up, invokes from out of a recognition that mainstream insistence lacks the rare, Persian, poetic dash which she, almost uniquely, navigates by. Near the end of the roll of the apple, the sloped street offers another moment of inertia, where a kid races after a soccer ball going amiss; but going right within the big picture. The sense of play is in the air; and a comprehensive sense of play is what is missing in the village, in Iran and in the entire planet. This, not some flaccid notion of the esoteric, where a clever entertainer dupes a ponderously stupid regime, is where Kiarostami does his work, in conjunction with one or two friends. (The other instance of misplaced powers, namely, that Behzad comes of age by learning from his hosts, is an exercise in myopia.)

The schoolboy nephew, Farzad, of the one who could see a good thing going, is befriended by Behzad in the capacity of a possible subject for future gains. Farzad is an earnest and noticeably self-possessed child, refreshingly devoid of attitude (making him a strong contrast to the “engineer.” His trousers are balloon-like pantaloons and he doesn’t seem to care that they’re not cool. His theme throughout, in many contexts, is the importance of doing well in impending “exams.” Having, by sheer instinct, already cleared many significant hurdles, he stands within this seeming whimsy as posing the difference between a test and an exam. Whereas Behzad—well-ensconced as an engineer, a calculation expert—could readily knock over any number of problems, exams, he hasn’t twigged on to that test which makes the difference.

With the full weight pressing down upon this bemusing incident now detectable, our goal is to find the distant soulmate to Close-Up’s Mrs. Ahankhah. The narrative turns particularly abrasive when Behzad gives a lift to a young man whom we find to be Farzad’s teacher headed to school with the day’s next exam. The protagonist is hit with his own exam by way of the teacher’s divulging that he had learned from the kid what’s really up with those V.I.Ps. This leads to the passenger’s spitting out (itching to break bad news) the dubious features of those funeral ceremonies. “How can I put it? It’s painful!” His mother carries two nasty scars on her face due to an apparent necessity to show the husband’s boss (who has suffered a loss) how deeply they care for him (and thus being immune to dismissal). “There was a great deal of pressure. They all needed work…” The young modernist, with no credence for pre-industrial commiseration, leaves the Land Rover on reaching the school, and only then do we see that he is crippled, requiring a crutch at one arm and a cane at the other. His parting shot is, “Don’t tell the kid what I told you…” But another parting shot is the frigid, resentful, self-pity of the Helsinki cab fares and the king of complainers, the Helsinki cabby, in the final phase of Jarmusch’s Night on Earth (1991). “Let me tell you, I think that the origins of this ceremony are bound to the economy,” is a feeble entity’s shallowing out the possibly primal currents there to be tested by a serious candidate. The exam-man’s exam-in-session involves Farzad the exam novice’s coming up to Behzad in his parked car and in distress about a question he needs a quick answer to. “What happens to the Good and Evil on Judgment Day?” Leading with an ass-backward smart-ass gambit as prefaced by, “That’s obvious,” he eventually trots out the formula, “The Good go to heaven, the Evil to hell.”

The “engineer” exposed—and having been burned by the corrosive tonality of the schoolteacher—comes to a moment when that penchant for exam-winning problem-solving runs dry in face of the test no one alludes to. On hearing of the boy’s indiscretion, the self-styled cool guy assures the long-faced lefty, “[When I was a kid] I think I enjoyed telling it more than I did keeping it a secret.” When next they meet up at the porch where Farzad regularly delivers bread made by his mother, the somewhat shaken big city trend-setter asks the boy headed for becoming only too good at providing answers, “Do you think I’m bad?” “You’re good,” his fleeting friend politely and mistakenly declares. One of the unique insights of Kiarostami’s film being that you can definitely be too old, too weak, to take on and maintain the test. After a few more unrewarding conferences with the bottom-line female producer, by way of going crazy to reach high ground, Behzad gets around to the boy’s spilling the beans about putting the town in a sensational light, he pronounces that he wants no more of that bread source and he, thinking to be pulling rank, asks, petulantly, “Listen, Kid, can’t you hold your tongue? Don’t come back…” Soon he’s mending fences with the remarkably balanced boy, using the same phrase current with the one close to death, “give up the ghost,” for his resorting to feebleness when under high pressure. “You go crazy, you blow up…” (This outreach then becoming shredded by that phone.) On the return from the so-called heights, he offers a lift to a number of kids coming home from exam-school. Farzad is there, but he declines the offer, being acute to the point of knowing that the lack of control is chronic and the optics of cool are fraudulent. “I apologized!’ is the engineer’s not getting it.

In a series of encounters with his near-neighbors, he turns on the liberal cosmopolitan tap being sure-fire input to secure, in the eyes of others and his own, an unimpeachable bedrock, which that constituency might term a “treasure.” Being a believer in local color, he searches out a source of fresh milk and finds it from an informative, pregnant, youngish woman who proudly tells him that the next will be the tenth. (The acquiring of the milk being the pinnacle of the film; and appearing after some more preparation.) The smoothie (seen at length fastidiously shaving, like Jarmusch’s Dead Man and Melville’s Dead Man Samourai) butters her up with, “I see you’re not idle… Your harvest will soon be ripe. Congratulations… May God preserve them…” (In his first steeplechase phone call, his parents are on the line and he cuts them up the way Willie would sneer and bitch at his hard-core Hungarian aunt. “I told you not to call… Don’t ask me that now…” The trendy Iranian, however, smooths things over with, “Are you better, Father… I’ll be back for the seventh day of mourning…”)

Behzad’s less than gratifying wrap-up of TV gold entails the local doctor, a dispensary of hard-headed skepticism and thereby a close-spiritual-kin to the schoolteacher. On one of his visits to the communications heights (coincidentally the site of the cemetery) he comes across a man digging a well, who unearths an ancient thigh-bone and presents it to the notable, who eyes it as another point of departure for his endless and lucrative diversions as lightly touching upon his flirtation with testing. A subsequent visit reveals that the excavation has hit a fault, leaving the worker in dire straits. The corporate good-citizen races about in rounding up a rescue-party, which includes the doc. Here, on the home-stretch of a narrative climax which, like the big-deal/ small-deal of the trial in Close-Up, is an anti-climax, we can report that the trajectory of the rescued laborer entails the engineer’s prompting the medic to provide some definiteness about the lady with no purchase upon rescue. (Like the apple and the soccer ball, inertia is the mover and shaker’s strong suit; and despite ripples amidst lively livestock, glowing farmland and soaring, mountainous wilderness, the test palpably falls flat—his aggrieved and confused visage more accurate than his laudable words and deeds, along with an imposing physical demeanor heavy on forceful dashing about and light on cogent coordination.) By the time the ancient villager does give up the ghost (a term for something the mystery of which he can’t engage), he’s become so depressed by the defeat he’s experienced on foreign turf that he detaches himself from the hoped-for moment of (easily accessible) vision. He throws that archaeological perk into a rapidly coursing mountain stream, a site of the dynamic sensuality which he’s been embarrassed by, though an embarrassment very likely to be confined to a successful exam, in lieu of enduring a test.

(There is an extended dialogue between the engineer and that other technician with dubious topspin, which, though following the key revelatory moment we’re climbing toward, should be savored at this point. Apropos of the accident victim, the Good Samaritan asks, soap opera, style, “Will he make it, Doctor!” “Yes,” is the assurance. “He just needed oxygen… Oxygen will save him…” Behzad, with an ulterior motive, then urges the oxygen-believer to examine what the photo-journalist in Close-Up calls “a hot news item.” On the way, on the doctor’s motorcycle, the bundle of nerves asks if he’d mind his smoking. The reply is both wise and unwise. “The air is so pure here. It’ll take more than your cigarette to pollute it…” [How about eons of reflexive and resentful answers?]. More half-truths are on tap. “I don’t have a specialty… That way I look after the whole body… If I specialized I’d be limited…” [which presupposes he isn’t]. He informs the newcomer that he has few patients, folk medicine probably more trusted. “If I’m no use to others, at least I make the most of life. I observe nature” [Is observation enough?]. On reaching the destination, there is the limited protagonist’s unsuccessful scramble amidst the houses on the mountain to find his cronies to alert them of the time-frame for a news blast-off—leaving him even more rootless and unsatisfied. He returns to the man of science and rides with him back to his vehicle. And with the new mission of picking up the pain-killers for the hot news, there is this second leg of the information spiel. “I’m like a general without an army,” the authority of life emotes. [Were that he could see—and navigate—major population paucity!] He warns the pills-buyer that special vigor is required for getting the full prescription from grasping, advantage-ravenous, rural pharmacists. “You have to be very determined” [in the mode of exams; but a wayward thrust of test obtains]. “She’s just a bag of bones,” is the assessment of the general, anticipating her demise at any moment. The bag of bones being a portrayal by pretty much all and sundry, accordingly their tandem passes through wind-blown golden grain ripening systematically against a light-blue sky and a swirl of arresting flora on a hill. But beyond that mundane dimension, there it is to be relished for its transcending earthy, creative poetry; there it is to pay homage, if only… Following up that missed opportunity, the man with lots of time on his hands cites the Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam, with its consumer report of, “Prefer the present” [as if sneering at crude ancient promises of immortality is where the buck stops]. “Death is the worst, leaving God’s world… It means you’ll never be coming back…” [Being stunned and cringing is much worse]. The lady dies that night. The engineer—a close-cousin of Mrs. Ahankhah’s engineer sons who dabble in dramatic art—perceives the mourning underway and, as dawn breaks, he’s galvanized to seal the deal; but his galvanic capacity shows being infected, polluted. He plods to his car, the roadway there filled with a procession of many women. He snaps photos and rather uncomfortably exchanges a weak smile with someone he’s met in the course of being an “honored guest,” someone presumably contributing by the ascent of “telecommunications.” Taking the bone, as in “bag of bones,” from the dashboard, he flings it into the stream along the banks of which goats graze and their presence is anything but inert. That paradox might haunt him during the day of “hot news.” But what are the chances of resolve leading to a generalship without an army?)

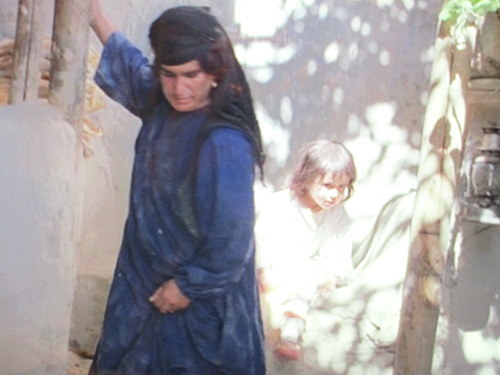

The odds against his turning the tide are most vividly revealed by the film’s center of gravity. Moreover, the new entry in this dialogue constitutes the only true innovator and poet in this deluge of the shabby new and shabby verse. One afternoon, stung by his intuition that Farzad is close to shunning him, a pensive Behzad prepares what he hopes will restore his high ground of gratifying appreciation of the limited but worthy proletarians. He has Farzad fetch him a bowl and then makes his way to a milk-seller. As he strides along, eyes downward, someone along the way calls out, “May you be proud” (and the everyday wish, “May god give you good health”). Stumbling upon the wrong address, he encounters a cordial woman and her young daughter. The former in black, the latter in white, they and the texture and color of their entryway offer optics of subtle and soaring power. (A cinematic prelude to a most unlikely pacesetter.) Moving next door to the milk specialist, especially cherished in the rocky terrain while nearly all the cattle are off some distance in the fields, he is directed to a dark entrance within the overarching rock and given assurance, “There’s a hurricane lamp, it’s not dark…” It’s dark, alright, and uniquely strange. “Zarehere, this gentleman needs milk,” is the fanfare by which the dude stumbles in primeval blackness and hears a cow mooing. “Is anyone here?”/ “Come in.”/ “How can you milk in here?”/ “I’m used to it. I work here… You’ll get used to it if you stay…” And the engineer’s mea culpa follows immediately: “I’ll be gone before I’m used to it.” Perhaps thinking it’s some kind of club or bordello, he shifts into recitation that might endear him in Tehran amongst the free thinkers. “If you come to my house/ Oh kind one, bring me the lamp and a window through which/ I can watch the crowd in the happy street…” Her reply, “What?” places her somewhere else than amidst one of the numerous precursors of extra-cool. Hearing that she is 16 and had spent 5 years in school (learning to succeed in exams) before resuming her education, the floundering general in a dark place who commands a number of movers and shakers pushes into her face an iconic woman poet, feminist, media and academic darling (sort of like widely beloved “rebel” filmmaker, Mohsen Makhmalbaf, turning up in Close-Up). “Do you know who Forough is?” She mentions the daughter of a local lady. “No,” he chides, “the one I’m talking about is a poet!” Not being met with wild approval, he attempts to define her lowly status by which to impress upon her the region of such divinity as he has introduced. “What’s your name?” She being definitely not recognizing a friend, she remains silent. “It doesn’t matter,” he politely ticks her off. With that, he thinks the way to maintain the upper hand is by reciting one of the luminary’s gems which she will forever miss the glories of, buried down there in futility. “It will occupy us while you milk.” “In my night, so brief, alas/ The wind is about to meet the leaves…” [He makes sure she sees it’s a big-league version of her and the oxygen-saved, solitary, well-digging, bush-league boyfriend of her’s, Yossef, whom Behzad saw being visited by her up at the cemetery/ phone-zone. Only, there is a vast difference between the calculating provocativeness of the pop star and the two lovers who work in dark caves by which to make a star-crossed purchase upon reaching the stars without the benefit of media-clever “radicals”]. Going forward, in a matter of speaking, there is: “My night so brief is filled/ with devastating anguish/ One second, and then nothing… The wind will carry us” [inertia to the fore]. The no-name says, “The bowl is full…” He replies, a bit frazzled, “Yes! Yes!” And he resumes, with the sublime, “The wind will carry us…” A bit testy, while seeming to be an avatar of advanced civilization, he urges her to allow him to see her face (the little lamp-light only directed toward the cow’s milk). “So at least let me know his (Yossef’s) taste.” (We, on the other hand, are getting an industrial look at his taste.) Ushering the alien to the mouth of the cave and good-old mundane terra firma, she is curious about the background of what passes for sublimity amongst arbiters of taste. “How long did she study?” Behzad tells her, “You know, writing poetry has nothing to do with diplomas. If you have talent, you can do it too…”

1 note

·

View note