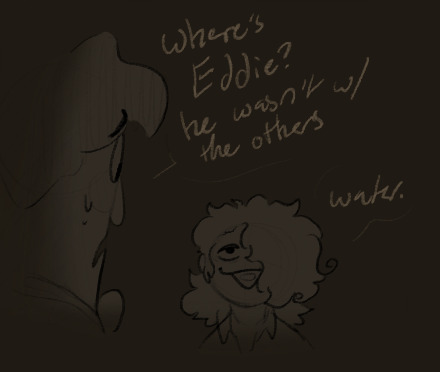

#and eddies just. facedown in water somewhere

Note

I've been visualbly imagining Eddie just laying there in a lake for 2 days now it's just so fucking funny to think about.

(Referring to that one post that asked where Eddie was sleeping.)

tbh it's been a running gag within the confines of my Imaginings <3 and it Is so fucking funny you're so right <3

he's in ↓↓ the water ↓↓

#honestly so tempted to find a way to work it into the au canon#like everyone else is nice n cozy in the storage room#and eddies just. facedown in water somewhere#it'd be impossible for the smaller puppets to remove him#hed be So waterlogged.... so heavy.....#LMFAO what if wally accidentally dropped him into a large puddle#and couldn't drag him out again#he'd have to just use scripts w/o eddie in em for sally's 'bedtime stories'#hm... but other factors.... ok it might have to remain a silly Non-Au-Canon joke#one i am fond of#scribble salad#wh lights out au#the water damage would be too great for him to survive i think#yk if i ever write a fic for this#i Could include a brief scene where eddie is indeed dropped in water#and wally & frank have to go get like. poppy to drag him out#as a lil nod to the joke....

427 notes

·

View notes

Photo

“The boy in the bassinet”

This is a sad story, but also a beautiful one.

Beneath the harsh glare of the midnight moon, late in the summer of 1898, a young woman launched a rickety rowboat off the sandy shoreline of Adams Lake. Nestled securely in the bow was her only son, a hearty infant who squawked delighted at the night sky as she struggled with the oars.

A mother’s love is a mysterious, inexplicable thing, and we will never know for sure what exactly inspired this young woman to take that fateful late night voyage. She was flush with youth, but also heartbroken, and convinced there was only one way to ensure a prosperous future for her progeny. The whispering wind had carried her here, and now it was the lapping waves that she put her faith in. The currents, she trusted, would take her where she needed to be.

After rowing through sheet after sheet of dancing mist, out into the middle of the lake, she help up her lantern to illuminate the blackness surrounding her. She couldn’t see shore in any direction as the boat swayed and rocked beneath her bare feet. Reaching into the the cool waters with one hand, she wondered if she would have the strength to go through with her plan. If she allowed herself to doubt, to fear, then she might be tempted to turn the boat around. Instead she decided to trust her instincts, and the wise voices groaning stoically from the trees, and put her faith in a force much more powerful than herself.

Less than a year earlier she’d been living as a healer and shaman, resolute in her solitary status, when she happened upon a young trapper en route to the Yukon. Men of all stripes were flooding north for the Gold Rush, all possessed by the same delusion, and his grandiose dreams were no different. She loved the way he told stories, though, how he conjured up visions of the future and rhapsodized about their imagined family. Late at night in her teepee she would lay in his snoring arms and wonder if he actually believed his own pretty lies.

By the time her pregnancy was apparent to those around her the strapping trapper had been gone for months. As the seasons changed and her belly swelled, the mother sometimes wondered if he hadn’t been some sort of apparition, a supernatural trick. Was he even human, really? And would he ever return to meet the child he left inside her?

As the woman scanned the darkness, her dress whipping lazily around her shins, she reflected on everything that had brought her to this moment. It wasn’t that she didn’t love her son—quite the opposite! Somewhere during her pregnancy she’d become filled with a holy conviction that her son had a special destiny ahead of him, that he’d been born on the mouth of the Adams River for some preordained purpose. It would break her heart all over again, saying goodbye to him, but that’s what she had to do.

The boy burped at the front of the boat, batting his tiny fists. Onshore he’d been asleep, but the rocking of the waves had awoken him. The wind was beginning to gust, the air was thick with moisture, and all around them the shadows swirled. The mother crouched down to his bassinet and ran one wet finger across his forehead, pushing back a tiny forelock of blond hair.

“You may forget me, sweet child, but I will never forget you. The journey in front of you is yours alone, but my spirit will follow as long as you live. You’re a part of me, just as I’m a part of you.”

With these words she hoisted the bassinet, which she’d constructed from twigs and branches from the forest surrounding her hermitage, and lowered it into the black water beside the rowboat. Her son giggled and spat, lolling his head from one side to the other. He was exactly three months old as his mother took a deep, tortured sigh and released her grip. Tears free-flowed down her cheeks, dribbling on to his face and chest.

“Goodbye, my boy.”

Almost immediately the current took ahold of the bassinet, sweeping him into the mist and out of sight. Legend says the mother instantly regretted her decision, that she spent the remainder of that night desperately searching through the fog, shouting out his birth name. Even to this day boaters report hearing her mournful ululations echo across the water. Had the spirits tricked her? Had the universe used her as a mere vessel, only to snatch away the fruits of her labour? Lightning streaked across the sky as she shrieked, her hair hanging around her face in wet tangles, and she leapt into the icy waters to be never seen again. Each person must decide for themselves if they believe she eventually found peace, deep below the surface, among the lake spirits of lore.

Early the next morning, as a fiery red sun appeared burning on the horizon, the boy’s bassinet drifted past a logging operation at the base of Adams Lake. It swirled across the surface, bumping once or twice against some jutting rocks near shore, then bobbed past a quartet of loggers who were still drinking from the night before. They were hunched over a card game, chugging whiskey and smoking hand-rolled cigarillos. None of them thought to glance out in the direction of the lake, where a large boom of bundled logs was affixed to a piling. That was the next shipment to send downriver, but it was still hours before they had to clock in. The boy drifted by listening to the cacophony of their barbarous voices.

Eventually the bassinet began to pick up speed. The lake was constricting as it wound down towards the choke-point where it transitioned to Lower Adams River. An eagle lazy-flapped overhead, circling the bassinet, then landed on a towering perch to oversee the boy’s passage. It had gotten used to human habitation but had never seen an infant before. Curious, it decided to swoop low to the surface for a better look. The boy screamed in excitement as it neared, startling the proud bird, but eventually it decided the creature meant him no harm. The eagle landed on the edge of the bassinet and looked the boy full in the face, seeing that he was blameless and vulnerable. It doubted this child could survive the serpentine trip down to the Shuswap without help.

By this point the river was thick-packed with salmon in the midst of spawning season, and the surface of the water was the colour of blood. The eagle wrenched one from the river and viciously pecked it apart, shoving the boy shreds of fish flesh with its beak. The boy squished the salmon between his fingers and smeared it on his face, but he ate too. The eagle kept dismembering the fish and the boy kept eating until there was nothing left but a sloppy skeleton. The eagle marvelled at the child’s appetite and once again took wing, following the boy’s progress at a distance. The little raft continued its lackadaisical descent, getting pulled into eddies then swept through roiling waves. Through it all the little passenger never cried, or wailed for his mother, but rather hooted and laughed through the rollicking chaos of the rapids.

Finally, by that afternoon, the boy’s bassinet began the descent towards the Adams River Gorge. Cliff faces dotted with pictographs jutted out of the foliage, and the river narrowed as the current continued to pick up speed. A team of Indigenous fishermen were perched on the rock ledges brandishing long-handled dip nets, and they were scooping bucketfuls of fish from the raging, watery chaos below. They sang together, cheering with each new haul, as the women and children sorted the newly caught fish at a small beach downstream. The food they harvested would be used year-round to sustain their population, and it was these salmon that made their entire lifestyle possible. One of the fishermen was taking a momentary break, dangling his feet off the cliff, when he saw the boy approaching the canyon. At first he thought it was some sort of animal, maybe the head of a swimming bear, but eventually he could make out the baby’s features and knew the canyon would mean a quick death for him.

That man’s name may be lost to history, but what he did next will be long remembered. He threw aside his fishing equipment and sprinted to an outcropping upstream, a hundred feet above the boy, then hurled himself into the current. His people had been fishing in the canyon for 10,000 years and knew every nuance and rock ledge, every cave and crack and fissure, but nobody had ever jumped from that spot. The other fisherman cried out in alarm, confused, as their compatriot hurtled through the air. What was he thinking? Didn’t he know the water level was too high, the rapid too powerful? The men were dumb-founded at first, wondering if they had just witnessed an impromptu suicide.

The man reached the bassinet just as a curling wave flipped it, sending the infant sprawling facedown in the water. He took ahold of the kid by one ankle, hoisting him out of the water, as he frantically paddled for shore. His friends were shouting at him now, running down to the river’s edge, reaching out their dip nets to save him. The man knew he could grab ahold of one and save himself, but that would mean letting go of the baby. Instead he rolled on to his back and held the child aloft, like an offering to the sky. He knew that if they could make it through the next thirty seconds there would be calm water waiting for them at the bottom.

Unfortunately, the river had other plans. As he rounded the bend of the canyon the man beheld a beastly wave hungry for carnage. Instinctively he understood, without even processing it, that he was looking at the instrument of his death. The wave was thrashing relentlessly into the cliff wall and sucking everything deep underwater, drunk on destruction. And though he only had a few moments to think, the man knew exactly what he had to accomplish with his final act on this earth. Rearing up with a mighty kick, he swung the baby overhead by the ankle and hurled him towards one of his friends perched on the cliff walls. Within seconds he’d disappeared into the wave, and out of sight, but the baby was giggling content from where he hung in a drooping dip net.

Later that evening the tribe gathered on the beach of the canyon, surrounded by their salmon catch. The man’s lifeless body was carefully arranged in the sand, his arms neatly tucked across his chest. Women wailed and mourned while the men muttered in concerned, angry voices. Who was this child? The man had a wife, and kids, so why would he give his life for some white stranger? Some argued it was a good omen, while others were convinced it was bad. They argued late into the night, standing around their beach fire and fighting about the boy’s fate.

“He came from the river, he should go back to the river!” said one tribe member.

“Who knows how many more lives he could cost us?” asked another.

Finally, a wizened elder named Quaalaout spoke up. For hours she’d stayed silent, listening patiently to the bickering, but everyone quieted once they heard her soft whisper of a voice. She was three feet tall, with waist-length white hair, and had been alive for nearly two centuries. She waddled to the edge of the flames and looked at all the rapt faces staring out of the darkness at her, then she sighed. She’d long wondered why the Creator had kept her alive this long, why she’d been waiting all these years on the shores of Adams River, and now she understood.

“We have built our lives around this river. It nourishes us, it sustains us, it keeps us going from one generation to the next. Because of the river, we need never thirst. We were hungry, so the river brought us salmon. Men live and die, but the river remains. As a people we have always put our faith in the river, and we must put our faith in it now. We know not its reasons, but it has brought us one man and taken another. Who are we to question its reasons?” she said.

Quaalaout then reached down to lift the baby, which was nearly half her size. She grunted from the weight, then positioned him on her hip. She took a long, quiet moment before saying anything else. Hundreds of faces stared out at her. Then she explained that the boy would be the newest member of the tribe and would be named “Joe-tsuschecw” — a word that meant “river’s gift” in her language. She heard some murmurings of disapproval, while others chattered excitedly, as she lifted him up for them to see.

“We will call him Shuswap Joe.”

The Kootenay Goon

0 notes