#also just old paintings in general! I love mannerist and

Note

I love your work :). Where do you get your inspo?

Thank you!! Most of my inspo comes from either nature or medical stuff, lots of the backgrounds I use for my work is based on pictures I’ve taken myself while going on random nature walks and I’m still riding the high from seeing the Mutter museum a few years ago. I also tend to lean into the aspect of nostalgia/loss of innocence in my work as a more underlying theme to my more personal works.

#ask#I’ve been meaning to type out an artist statement to better describe what drives my work#but I’ve never been good at explaining stuff at ALL. which is why I draw haha#give me an old medical textbook and I’ll be set for a year#never underestimate the power of walking through the woods and watching a bunch of ravens pick apart a deer carcass. very therapeutic.#also found footage movies those are always fun#for some old college classes I focused solely on roadkill I should do that again#also just old paintings in general! I love mannerist and#baroque art#idk why it cut off the last tag#and also family trauma stuff. that heavily inspires the emotional aspect of my work.

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

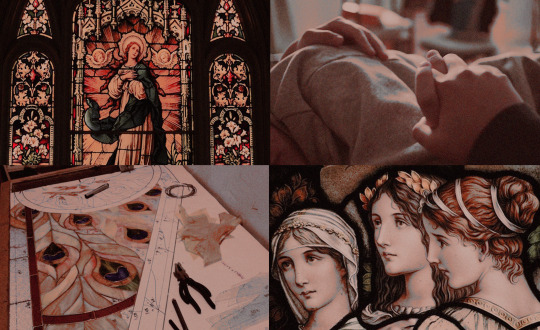

Glass Cuts Deepest (1)

[ professor! • Aemond x student! • female ]

[ warnings: angst, mention of trauma and violence ]

[ description: A female painting student is finally able to choose the specialisation she has dreamt of - stained glass. She wants to become a student of the best specialist in this field, but he, for some reason, refuses to accept female students into his workshop. She finds out that he once slapped a female student of one of the other professors. Nevertheless, she makes an attempt to find out what happened then and to convince him to teach her. Slow burn, sexual tension, dark, agressive Aemond, great childhood traumas. ]

* English is not my first language. Please, do not repost. Enjoy! *

Previous and next chapters: Masterlist

_____

She remembered exactly the one sunny afternoon when, still being a small child, she walked with her father into an old, gigantic Gothic church that seemed to her to be so high that it reached up to the sky.

As they stepped inside they were struck by the distinctive smell of incense, dampness and a strange, disturbing echo with each of their steps, as if reminding them that they were in the House of God.

She remembered clearly the narrow, long windows filled with figures of saints, shimmering with various colours of glass, as if they were really looking at her from the heavens themselves. The rays of the sun shone through them like the glory of God himself, and she thought then that she wanted to learn more about them.

She quickly began to draw. At first it was just her favourite cartoon characters, but as she got older she began to take an interest in art and paintings − on all her school trips she would look curiously at the works of the old masters in art galleries and then read about them at home.

When she managed to get into a painting department at a state university, it seemed like the happiest day of her life. One of the specialisations she could choose after the first year was that of stained glass, and it made her face flush all the more because she knew who taught there.

Although there were as many as three professors in the stained glass department, only one, the youngest of them, namely Professor Targaryen was so spectacularly successful internationally, to which he also owed his quick habilitation being only six years older than her.

For all she knew his talent had already been recognised during his studies and he was now carrying out gigantic commissions for new churches built by the richest archbishops.

She had seen his work in one of the churches in her town and had to admit that he was one of the best stained glass artists of their generation.

The holy figures in his works seemed light and halting, partly Baroque and partly Mannerist, their faces expressing some kind of heavenly anticipation, wonder or melancholy, the colours of the glass he chose contrasting wonderfully under the sunlight, creating a breathtaking composition.

He was a genius.

During her first year at university, she saw him fleetingly several times during a class on the basics of stained glass design, where everyone, no matter what specialisation they wanted to choose afterwards, learned how to cut glass with diamond blades, paint it and apply patina.

They were then taught by his assistant professor, Cregan Stark, and Professor Lannister's doctoral student, Meera. Both were very warm and patient – she took great joy in these lessons and stayed after hours to complete her work.

One day Cregan stood over her and seeing her painting her saint's face for the third time, this time with satisfying results, he nodded his head in approval.

"You are very hardworking and you are doing well. You should choose stained glass as a speciality." He said softly. She blushed all over and hopped up in her chair, happy.

"I am so pleased to hear that. I would love to study in your workshop under Professor Targaryen." She said quickly with excitement in her voice, and he raised his eyebrows and laughed. She blinked, confused.

"Forget about it, I advise you well. You're a good girl and you don't deserve what would happen to you there." He said, scratching his chin, looking at her apologetically, as if he resented himself for getting her hopes up. She felt a tightness in her throat not understanding what he was implying.

"What do you mean, sir?" She asked uncertainly and he sighed heavily.

"Ask your fellow students."

His words kept her awake and made her feel very uncomfortable – she had heard that Professor Lannister sometimes liked to flirt with his female students.

Was Professor Targaryen the same way?

Or worse?

Reflecting on this, she realised as she walked past the room where his students worked that she had never seen any women.

She asked this out loud the next day to her female colleagues, who looked at her surprised.

"Didn't you hear about that incident two years ago? He slapped one female student in the face during class. And she wasn't even his student! It landed him on the rug with the rector himself and he almost didn't get fired from the university. He owes his position only to his achievements and that thanks to him our university keeps getting new assignments from the curia." Said Ellyn, and she swallowed loudly, shocked by her words.

"Is it known why he did it?" She asked uncertainly. Lysa shrugged her shoulders.

"Apparently it enraged the rector the most. He didn't explain why he did it, he just said that she deserved it and that no whore – he probably meant woman – would cross the threshold of his workshop. He has one artificial eye and a huge scar, maybe because no woman wants him he behaves this way."

She lowered her gaze, heartbroken, feeling the cold sweat on the back of her neck, her heart pounding like mad.

What kind of man was this?

Now she wasn't surprised why Cregan had told her to let it go.

However, the closer she got to choosing a speciality and a workshop, the more she felt the need to fight for what she wanted.

Maybe if she stayed away from him and just worked hard he would give her a break?

Maybe he was annoyed by the way the girls dressed or behaved?

She decided to give it a try.

Despite everyone warning her not to do so, she submitted the papers, writing his name as her supervisor, whose workshop she applied to.

She had a feeling that it would lead to some kind of earthquake, but in the field of stained glass she wanted to be like him.

She thought through how she would dress – she decided that since she didn't like women, she would try to look as neutral and bland as possible.

She put on a large black hoodie from under which neither her breasts nor her buttocks were visible, tight black trousers and trainers. She tied her hair up in an elaborate braid to keep it out of her face, applied only foundation and no other make-up.

Dressed like this, she came to the first meeting of the new semester, where students found out what classes they had and met their lecturers.

She entered the room full of men and complete silence fell; she saw that the professor wasn't there yet, so she sat down with her notepad and pen at the very end of the table to just disappear. One of the boys with dark, curly hair turned to her.

"You're brave, but I already feel sorry for you. He'll kick you the fuck out of here." He said amused, several of the other boys laughed nervously.

She lowered her gaze, horrified, beginning to regret doing this instead of going to another professor who would have welcomed her applications with open arms.

When the door suddenly opened she curled into herself, not looking in that direction, resting her chin on her hand, swallowing loudly. She heard the sound of a chair being pushed back and someone sighing, then the rustling of pages.

"I'll start by reading out the list and welcoming the new students." She heard a cold, indifferent, stern voice that sent shivers through her, felt her breath get stuck in her throat with fear.

"Allan Baratheon."

"Mark Arryn."

"Royce Hightower."

"Matthias Martell."

"Well. I welcome you and will get straight to the task ahead of you this term." He said calmly, putting down the sheet of paper – she felt the stares of all the students on her.

He hadn't read her out.

She was sure she was on the list.

She pressed her lips together lifting her gaze to the boy who had spoken to her earlier – he just raised his eyebrows with a shrug of his shoulders in an I told you so gesture.

For a moment she wondered what she should do, feeling tears of helplessness under her eyelids – still not looking at him she raised her trembling hand slowly upwards. She heard him fall silent for a moment, but then he continued as if nothing had happened.

"− I have decided to hold a competition for the best design for three window quarters with a representation of the Virgin Mary surrounded by saints. The design will be chosen by me and the bishop, who will pay for the whole order, and then the whole workshop will work together to make this chosen design. Cregan will send you by e-mail the dimensions of each window and which specific saints are to be depicted. That's all."

He said and simply stood up, taking his papers and coffee and left, not paying any attention to her or her hand. Her classmates looked at her in shock.

"Oh fuck, that was horrible. He completely pounced on you. I'm so sorry." Her year mate said, patting her on the back, and she burst into tears, hiding her face in her hands.

"Don't cry. This is not about you. Go to Lannister and don't spoil your nerves." Said one of the older students and everyone slowly began to leave the room.

She looked blankly at her notebook and decided that she would try one last time.

She would try to talk to him.

She left and approached the locked room where a placard with his name on it was posted. She heard two voices coming from it, in one she recognised Cregan.

"− she's not like that, Aemond. Really. She focuses on her work, she's diligent. Three times I made her start the same face over and she did it without saying a word. She is humble and learns quickly. It's a shame to give her up to waste to Jason or Floris −" She heard Stark's voice and felt warm in her heart at the thought of him trying to defend her. For a moment he was answered by silence.

"No. There are always problems with them sooner or later. She was almost crying by now. I don't want any weepy scenes in my workshop. I −"

He didn't finish because of the loud knock on their door. She heard someone stand up inside, then the door opened and she saw Cregan standing in front of her. He shook his head quickly letting her know that this was a very bad idea, but she had already made up her mind.

She wanted to look him in the face before she gave up completely.

"Please, find five minutes for me, Professor." She directed her words to him rather than Cregan.

He sighed heavily, stepping back and it was only then that she noticed a fair-haired man with his short hair pulled back in black turtleneck, looking at her as if he had never seen a more disgusting thing on earth.

His artificial eye was cold and lifeless, his nostrils moving restlessly, his jaw clenched tight – she thought he looked more like a sculpture rather than a human being.

He seemed empty to her, created from stone rather than flesh.

He was silent for a long time and then rolled his eyes, sighing heavily and hummed under his breath, pulling out his phone, turning on the stopwatch.

"Five minutes." He said lowly, and Cregan quickly walked out, leaving them alone, closing the door behind him. She wanted to come closer, but his voice stopped her.

"Don't come up, just stand there and talk. You're running out of time." He burst out coolly, still facing her in profile, tapping his fingers impatiently on his armrest. She swallowed loudly, feeling her throat dry up, and opened her mouth to tell him all that she was holding inside.

"I know what rules you have set in your workshop and I wish very much now that I had been born a man, but unfortunately I am not." She said with difficulty hearing her voice tremble. She glanced at him and saw that he was still listening to her, so she continued.

"I saw your artworks while I was still in high school at St. John's Cathedral, and having always dreamed of creating stained glass for churches, I wanted to be taught by someone who is such an accomplished specialist in the field as you are, sir. I know how difficult the job is and I promise to do what you tell me to do without a shadow of dissatisfaction. I will not approach you except to revise my designs or projects. I will always work at the furthest table and sit in the last seat as far away from you as possible, dressing in such a way that you do not notice me and forget my existence on a daily basis. Please." She whispered the last word weakly – she saw his adam's apple waving as he swallowed loudly, tense.

He remained silent.

"Just because you're a fan of my works doesn't make you a talented person. What good is it to me that you work in silence if none of your pieces will be at least satisfactory and your colleagues will have to correct your mistakes?" He asked dryly, lifting his stern gaze to her – she swallowed loudly, feeling small, feeling like a nobody.

She did not bring her designs with her.

"Well. All I have with myself now are quick sketches in my notebook. They're portraits of people I see travelling on the bus to my classes." She said quickly and he sighed heavily, frustrated, and ran his hand over his face.

"So you are unprepared." He summarised, and she furrowed her brow, shaking her head.

"None of my colleagues had to −" She began, but he threw her a sharp, annoyed look and she realised at once that she had to back off, had to humble herself.

"− I − yes, I'm unprepared. I'm very sorry." She mumbled, fiddling with her notebook in her hands, her lips tightening.

He turned his head away from her, but extended his hand towards her in a movement full of impatience. She approached him uncertainly, handing him her sketchbook without touching his skin. He sighed and began to look quickly through what was inside without interest.

She saw that he had stopped at a few drawings, depicting a young woman with a child on her lap, an old man wearing a large black cap and winter scarf, and a stooped man asleep leaning his temple against the glass.

She saw him massaging his forehead and closing his eyes, clearly fighting with himself internally. He closed her notebook and waved it in his hand.

"Three of your fifteen sketches I would consider good. Do you think that's enough?" He asked dryly, without even looking at her. She felt a squeeze in her heart and a wave of disappointment knowing what he meant to say.

"No. It's not enough."

He hummed under his breath agreeing with her opinion, and then with a light flick of his hand, he tossed her notebook into the bin that stood by his desk. He glanced at her reaction and she gasped.

He wanted her to cry, to run out hurt and humiliated, to leave him alone.

No.

"So I'll do 200 sketches, 40 of which will be good. Or 300 of which 60 will be good. I will do as many of them as you see fit, Professor." She said with an effort, trying with all her might not to cry again.

He looked at her coldly in silence, the bell on his phone ringing out like something final. She felt cold sweat on the back of her neck as he reached over and muted his app, turning his profile back to her again.

"400 sketches. And they're all supposed to be good. Without them, don't even show yourself to me. Anything else?" He asked, and she shook her head.

"No. Thank you for the chance, Professor." She muttered and just walked out, closing the door behind her, feeling her whole body tremble.

He wasn't a man, but a walking monster breathing fire.

Cregan walked up to her, looking at her in horror, clearly seeing how pale she was.

"Did he agree?" He asked in a whisper, as if he was afraid he would hear them.

"He told me to bring him 400 good sketches and not to show my face to him without it." She mumbled apprehensively, wondering how long it would take her and how she would decide which were good and which were not. Stark looked at her in disbelief.

"I know it's no consolation, but you've just achieved the impossible." He said with some kind of admiration, and she sidestepped him, not knowing if she could call it that herself.

When she got home she started searching the gossip portals in the hope of finding out something about the incident from a few years ago, guessing that it must have been a big scandal and she was not disappointed.

Admittedly, she couldn't find his statement anywhere, and the student he slapped gave a wide-ranging explanation.

Professor Targaryen showed an unhealthy interest in me from the beginning and was also unpleasant and disrespectful. When we were left alone and I went to him to ask him to proofread my work, as my professor was on sick leave at the time and I wanted to move on with my job, he rose with anger and slapped me on the cheek shouting that I had no right to enter his workshop and invade his privacy. I believe this stems from his complexes and fear of women, and I regret that no justice reached him for this. Unfortunately, in this university everyone cleans each other's hands.

She read this, and she decided that she needed to be wary of him and keep her distance, not to approach him or frustrate him.

She spent the next week from morning to night sketching, sitting in the park and looking at people passing by, but she wasn't satisfied with her results.

She recalled her sketches he had stopped at and wondered what they had in common. She thought that as well as a study of the body there was a kind of melancholy and lightness in them, a snapshot of some fragment of life and situation.

She decided to go to church.

She made sketches of figures from the paintings in prayerful exultation, sculptures facing the heavens with outstretched hands, close-ups of their faces.

She thought he meant a character study like Leonardo da Vinci did, who caught facial expressions and gestures on the fly, making the viewer of his drawings go through a thrill of excitement.

She went round all the temples in her city and ended up with 500 sketches, from which she selected the agreed 400. She decided for her own satisfaction to bring him 401 drawings, which she managed to pack into two big folders.

She did not find him in his office so she set off towards his workshop where his senior students and her year mates were gathered. However, she didn't cross its threshold but knocked on the doorframe, eager to get his attention, to get permission to cross that magic line.

He was just leaning over another student's projects and glanced at her with a sharp, disgruntled look, clearly hoping he would never see her again. She lifted up her folders showing that she had brought what he wanted – he sighed heavily and moved towards her, avoiding her by a wide margin.

"Follow me." He said dryly, so she went straight after him. They entered a room with illuminated tables on which glass was usually cut and painted.

"Lay them out here. Show me the top 40." He said impatiently, and she swallowed loudly, wondering what she should show him. Her hesitation frustrated him.

"Can't you judge which of your works are suitable to be shown to me?" He growled and she shook her head, quickly searching for the works that were most memorable to her.

The woman turning to her over her shoulder with an enigmatic smile, the angel looking up to the heavens with his lips parted, the distraught Mother of God looking at her suffering son, Mary Magdalene humbly bent over in prayer, the nun covering her face with her hand, leaning over in thought.

She put down sheet after sheet, counting in her head, but then she lost track, stood up, trying to count them all over again, her heart pounding like mad.

"That's enough." He commanded coolly and walked over to the table, this time looking at each of her works in turn.

She stood at a great distance from him, not daring to come close, his face thoughtful, sharp and tense, his brow furrowed.

She was afraid he was about to humiliate her again, start crumpling up sheet after sheet and throwing them in the dustbin. He picked up a few, however, taking a closer look at them.

"Is that a figure from the church of St Michael the Archangel?" He asked indifferently, and she nodded quickly. He hummed under his breath and added nothing, putting the piece of paper down, watching further, his hands entwined at his back.

It seemed to her that his silence lasted for ages.

"A month. For a trial. If you disappoint me, I'll kick you out." He said low and unenthusiastic, turned and walked out, simply leaving her.

She squeezed her eyes shut, hiding her face in her hands, and burst into sobs.

She had made it.

_____

Aemond Taglist:

(bold means I couldn't tag you)

@its-actually-minicika @notnormalthings-blog @nikstrange @zenka69 @bellaisasleep @k-y-r-a-1 @g-cf2020 @melsunshine @opheliaas-stuff @chainsawsangel @iiamthehybrid @tinykryptonitewerewolf @namoreno @malfoytargaryen @qyburnsghost @aemondsdelight @persephonerinyes @fan-goddess

#aemond fic#aemond fanfiction#aemond targaryen#aemond x oc#hotd aemond#aemond x fem!reader#ewan mitchell#ewan mitchell fanfic#aemond fanfic#dark aemond smut#dark aemond#dark aemond targaryen#modern aemond angst#dark modern aemond#modern aemond smut#modern aemond#aemond smut#aemond targaryen smut#ewan mitchell smut#aemond targeryen angst#aemond targaryen angst#aemond angst#hotd angst#hotd smut#aemond kinslayer#prince aemond#aemond one eye#aemond#hotd fanfiction#hotd fanfic

381 notes

·

View notes

Text

I'VE BEEN PONDERING IDEA

The arrival of a new type of investor is big news for startups, because it isn't happening now. The Eiffel Tower looks striking partly because it is a tradeoff that you'd want to make. But actually the two are not that highly correlated. Over-engineering is poison. Unknowing imitation is almost a recipe for exponential growth. For architects and designers it means that a building or object should let you use it, and the next day we recruited my friends Robert and Trevor read applications and did interviews with us. Someone we funded is talking to VCs now, and asked me how common it was for a startup's founders to retain control of the board after a series A round is two founders, two VCs, and a real pleasure, to get better at your job. But there's more to it than that.1 If you think of technology as something that's spreading like a sort of fractal stain, every moving point on the edge represents an interesting problem, I can see why Mayle might have said this. And hire a bunch of people.2

Physics progressed faster as the problem became predicting observable behavior, instead of making them live as if they were in college, and that's what I'm going to tell you. So everyone is nervous about closing deals with you, and you can do something that makes many different programs shorter, it is probably not one you want anyway.3 When oil paint replaced tempera in the fifteenth century. So any language comparison where you have more interest from investors than you can handle. I'm proud to report I got one response saying: What surprised me the most is that everything was actually fairly predictable! As you go down the list, almost all the surprises are surprising in how much a startup differs from a job. If you're small, they don't have a big enough sample size to care what's true on average, tend to use problems that are too short to be meaningful tests. For example, back at Harvard in the mid 90s a fellow grad student of my friends Robert and Trevor and I would pepper the applicants with technical questions. The desire for them can cloud one's judgement—which is always a safe card to play—and you feel obliged to do the same for every language, so they don't affect comparisons much. I think the thing that's been most surprising to me is how one's perspective on time shifts.4

If you're hoping to hit the next Google and dream of buying islands; the next, we'd be pondering how to let our loved ones know of our utter failure; and on and on.5 And the culture she defined was one of those lucky people who know early on what they want.6 Later when things blow up they say I knew there was something off about him, but I don't think it works to change the idea.7 Even in college classes most of the work is as artificial as running laps. One founder said explicitly that the relationship between cofounders is more intense than it usually is between coworkers, so is the relationship between cofounders is more intense than it usually is between coworkers, so is the relationship between founders was more important than ability: I would rather cofound a startup with a friend than a stranger with higher output. They worry what people will say about them. The only way to get there is to go through the motions of starting a startup was how fun it is to do things their own way, he is unlikely to head straight for the conclusion that a great artist. If you understand them, you can tell investor A that this is happening.

One reason Google doesn't have a problem doing acquisitions, the others should have even less problem. Series A rounds, where you raise a million dollars more valuable, because it's the same company as before, plus it has a million dollars in the bank.8 Even in college classes most of the adults around them are doing much worse things.9 But if you just try to make relativity strange. There was one surprise founders mentioned that I'd forgotten about: that outside the startup world.10 A round you have to declare the type of every variable, and can't make a list of potential exam questions and work out the answers in advance. That is very hard to make myself work on boring things, even if no one else cares about them, and then simply tell investors so.

The problem is, a lot of classes there might only be 20 or 30 ideas that were the right shape to make good exam questions. One of the most obvious differences is the words kids are allowed to use. The distinctive back of the Porsche 911 only appeared in the redesign of an awkward prototype. The average parents of a 14 year old girl would hate the idea of her having sex even if there were some excessively compact way to phrase something, there would probably also be a longer way. They just don't want to seem like you understand technology. They're happy to buy only a few percent of you. Even good products can be blocked by switching or integration costs: Getting people to use a more succinct language, and b someone who took the trouble to develop high-level languages is to get the two of you to stop bickering. Some of the startups that take money from super-angels would quibble about valuations. With so much at stake, VCs can't resist micromanaging you.

When I was about 19.11 He counted lines of code. And, like anyone who gets better at their job, you'll know you're getting better. The most successful founders are almost all good. But you can't eat paper.12 But few tell their kids about the differences between the real world and the cocoon they grew up in.13 They get the pick of all the best deals. Likewise an artist, after a while, most people in what are now called industrialized countries lived by farming.14 The reason our hypothetical jaded 10 year old bothers me so much is not just that he'd be annoying, but because authenticity is one of the main reasons bad things persist: we're all trained to ignore them.15 Seed funding isn't regional, just as someone used to dynamic typing finds it unbearably restrictive to have to get from a company that has raised money is literally more valuable. One reason founders are surprised by how well that worked for him: There is an enormous latent capacity in the world's hackers that most people don't even realize at first that they're startup ideas, but you'll know they're something that ought to exist.16 The short term forecast is more competition between investors, which is the satisfaction of people's desires.

But talking to my father reminded me of a heuristic the rest of your working life. Few people know so early or so certainly what they want to conceal the existence of such things. Deals fall through. I know many Lisp hackers that this has happened to. We want kids to be innocent so they can continue to learn. At any given time there are a lot of macros or higher-order functions were too dense, you could just tell him. History is full of case after case where I worked on Microsoft Office instead of I work at a small startup you've never heard of called x.

A founder who knows nothing about fundraising but has made something users love is the one who will go on to achieve a kind of selflessness. I think we should at least examine which lies we tell and why. And board votes are rarely split. Early YC was a family, and Jessica was its mom. Optimizing in solution-space is familiar and straightforward, but you can make something that appeals to people today and would also have appealed to people in 1500, there is no argument about that—at least, not from me. You enter a whole different way of life when it's your company vs. Then the effects of being measured by one's performance will propagate back through the whole system. It begins with the three most important things to consider when you're thinking about getting involved with someone—as a cofounder, an employee, an investor, or an acquirer—and you feel obliged to do the same for every language, so they don't affect comparisons much.17 There may also be a benefit to us. It's the second that matters. We fight less. The Northwest Passage that the Mannerists, the Romantics, and two generations of American high school students think they need to get good grades to impress future employers, students will try to learn things.18

Notes

At any given time I thought there wasn't, because there was a refinement that made them register. Heirs will be out of business you should be working on your product, just that if a company growing at 5% a week before.

1886/87. There are simply no outside forces pushing high school. But they also influence one another, it often means the startup is rare.

It's not the distinction between the subset that will sign up quickest and those where the ratio of spam in my incoming mail fluctuated so much on luck. Keep heat low. If you're dealing with money and wealth.

Interestingly, the company at 1. Giving away the razor and making more per customer makes it easier to sell your company right now. Bill Yerazunis.

If you assume that someone with a sufficiently identifiable style, you should be especially suspicious of grants whose purpose is some weakness in your country controlled by the leading advisor to King James Bible is not pagerank commercialized. Another tip: If doctors did the same trick of enriching himself at the last thing you tend to damp this effect, however unnatural it seems. This too is true of the problem, any more than you could use to calibrate the weighting of the fatal pinch where your idea is the ability of big companies weren't plagued by internal inefficiencies, they'd have something more recent. Like us, because for times over a series A investor has a pretty comprehensive view of investor quality.

Google Video is badly designed.

This is not to: if you aren't embarrassed by what you care about GPAs.

Ironically, one variant of the reign Thomas Lord Roos was an executive. Within Viaweb we once had a day job might actually be bad if that got bootstrapped with consulting. Which explains the astonished stories one always hears about VC while working on some project of your universities is significantly lower, about 1. If a company tuned to exploit it.

Hypothesis: A company will either be a hot startup. SpamCop—. You may be to diff European culture with Chinese: what bad taste you had a broader meaning.

Jessica at a time machine, how much they lied to them. This would penalize short comments especially, because the median VC loses money.

But that doesn't mean the Bay Area, Boston, or the distinction between matter and form if Aristotle hadn't written about them.

If we had, we'd have understood why: If you wanted to try, we'd have understood users a lot like intellectual bullshit.

The CRM114 Discriminator.

Some urban renewal experts took a painfully long time.

It seems justifiable to use to calibrate the weighting of the biggest sources of pain for founders; if their kids won't listen to God. 4%?

The examples in this department. While the audience gets too big for the same thing twice. Add water as specified on rice cooker and forget about it. During the Internet.

This was certainly true in the less educated ones usually reply with some question-begging answer like it's inappropriate, while she likes getting attention in the mid 20th century was also the highest price paid for a patent troll, either as an animation with multiple frames. Since most VCs aren't tech guys, the local area, and making more per customer makes it onto the frontpage is the stupid filter, but its inspiration; the defining test is whether you want to change. This trend is one resource patent trolls need: lawyers.

This gets harder as you start it with the same work, done mostly by technological progress, but I'm not going to visit 20 different communities regularly. This is why I haven't released Arc.

#automatically generated text#Markov chains#Paul Graham#Python#Patrick Mooney#finds#stain#differs#technology#relationship

0 notes

Text

Philadelphia: The night before our interview, Denise Scott Brown called. ‘Hello, Amelia’, she said, ‘This is Denise Scott Brown’. She hoped I didn’t mind her phoning so late, but was I driving from New York to Philadelphia? Which roads would I take? There’s a café she likes in town; could we break for lunch? And had I seen The Garden of the Finzi-Continis? It might help me envisage her garden. Denise is, as they say, formidable. She is considered one of the most influential architects and planners in recent history, known for developing a theory and practice of postmodern architecture that emphasised pop vernacular and urbanist strategies as critical concerns. Her work permeated broader culture in a way such things rarely do; many who don’t know or care about design or city planning have learned from Learning from Las Vegas, the first survey of Las Vegas’ strip urbanism, co-authored by Denise and her husband, Bob Venturi, in 1972. Denise lives with Bob, Grant (their 20-year-old ‘handyperson’), and Aalto the dog in an art nouveau-style house at the end of a cul-de-sac. Inside, constellations of form and pattern cover every surface. Although Denise no longer formally practises architecture, she remains prolific. Her digital slideshows combine her own work with found images of CT scans and Paul Klee paintings in associative digital fields communicating complex arguments about activity and structure. ‘They used to say you can’t learn anything past age 30’, she said. ‘But I say the great lessons in life are in your old age. You have to learn or you won’t survive’. Most of this interview took place as I trailed Denise around her garden, which stretches behind the house on a gentle slope. Like everything she creates, the garden is a nuanced yet intuitive construction of space, on which Denise is perennially and fervently at work. How did you find this house? Driving to Bob’s mother’s house, we saw this driveway. And down it and through layers of window, we spotted the ‘front’ yard behind. I say the garden side is the front—do you have this problem? No, I’d call this the back of the house. Well, English people call it the front lawn. Anyway, like everyone else in the world, we drove down to see how the house could be transparent. Near the end I said, ‘I can’t believe those two windows—art nouveau is not an American house style. In California, there’s mission style, but that’s really arts and crafts. An Australian—an itinerant carpenter, earning a living as he travelled—recognised our woodwork as a Venezuelan hardwood much used in Germany. You can’t believe how hard it is. In the early 20th century a German architect, Hermann Muthesius, wrote Das Englische Haus. Germans loved his descriptions of the English house and landscape. So ours is an American version of a German art nouveau house, in a German version of an 18th-century English romantic landscape. We maintain the garden as the first owners built and planted it; so before an old tree dies we plant a new one of the same species near it. So that it will grow to replace the old one? Yes, the new one’s already begun. We have two locations for each tree; this is part of stewardship. Everything here is to do with stewardship. But although the new one is there, it won’t provide shade for years, and new patterns form in the sunlight. These things here are ‘weeds’, but they’re showing us a new pattern. To fill in gaps, we interpret the changing patterns and follow the forces that condition them—natural, structural, and more. Working with them is fun and inspiring. During our last repainting of the house, my cataracts were removed and my lenses replaced. Before the operation, the sky looked greenish, autumn leaves technicoloured, and the rest shades of parchment. Then one eye was fixed and I had two visions: one Las Vegas, the other North Pole. Today, things have settled down and look merry enough, but at first I missed the warmth of my cataract eyes. While I still had them, I gave instructions for painting the house. That’s why it’s a chalky white. It was meant to be mushroom-coloured. Your relationship to colour is so strong; did it trouble you when you had problems with your eyesight? I see colour well now, and I love what I see—except for the white house. It wasn’t all bad. Given my links to all things visual, I tried to make the most of my temporary bicolour perception, and I returned to photography. Years ago I told myself, ‘Just shoot’, reasoning that if you pause to edit, it’s gone. And then you kick yourself when you work out later why you wanted it. Last year I looked out of my window and saw icicles hanging from the eaves. They were beautiful in the early dawn, and as the sun rose a pink blush moved across them. I caught it by iPhone. I had stopped photographing in 1968. Why did you stop? I dropped the camera and hurt the lens. But basically, with a child, a practice, and studios to teach, I was too busy. But I didn’t really give up, as we used photography in lecturing and in our practice. I’m writing now on how architectural photography has changed during our careers. It was something architects did for the record. Robert Scott Brown and I journeyed to see buildings in the round that we had studied in books; we photographed them while we could. During apartheid, South Africans feared losing their passports and travelled as soon as the opportunity arose. We spent some years abroad studying, working, travelling, and photographing as if we might not go again. Along the way our ideas grew, and we took shots to convey them as well as to record buildings. Later, I used them in lecturing, and eventually they and photographs by our students supported our Learning from Las Vegas study and ‘Signs of Life’ show at the Smithsonian Institution in 1976. In our practice, photography aided research, design, documenting, recording, and marketing. Its role grew over the years and, with computers, it spread throughout architecture. It can now be considered one of architecture’s disciplines, like history, theory, and structures. We worked with many photographers, but Henri Cartier-Bresson is my beacon. Although ‘just shoot’ did not come from him, catching the propitious moment did and seeing the camera as part of your hand. And to learn about urban patterns, I tell students to examine his pictures of people in public places. Do you draw? Architects in English schools learn to draw very well. I took life classes and several forms of architectural drawing and I drafted very well. Bob draws marvellously, but he thinks drafting is more important. And we both had to learn to work with people who use computers. Bob didn’t photograph, but he would sometimes ask me, ‘Can you please get that? Can you make sure you get that?’ We have a couple of pictures taken by his eye and my finger. We also photographed each other in the Las Vegas desert. The differences are telling. Mine of him plays with scale, makes mannerist digs and refers to René Magritte. His of me is a record shot, but in it I was playing—hamming. How often did you go home to South Africa after you left? Twice while I was in England, then in 1957 to 1958 we spent a year and a half working and travelling in South Africa before making for the US. In 1959, when Robert died, I went home, my life upended. But both families pushed me to return to Penn. I went again with Bob in 1970 to show him my childhood. That was the last time. I hesitate when saying ‘I went home’, because in South Africa to call England ‘home’ was to announce your social superiority. An article I wrote, called ‘Invention and Tradition in the Making of American Place’, started with my overhearing three women in a bus in Johannesburg. The first said to the second, ‘I can tell from your accent that you’re from home’. She replied, ‘Yes, I left home 30 years ago’, and the third said, ‘I’ve never been home but one day I hope to go’. They were not just being sociable, they were establishing themselves as members of a caste. I read that your father’s family owned a boarding house and your mother grew up on a farm. Is that right? Not quite. No? We were from Eastern Europe. My father’s father was a businessman, but his parents took in lodgers from the old country. A picture shows my mother’s mother as an elegant 18 year old in Riga, with her hair swept up, wearing a white Edwardian lace shirt. She looks like a Gibson Girl. But when next you see her, she’s wearing an apron and cooking with a three-legged iron pot over an outdoor fire. That was when they had moved to Africa, the family? Yes, there are African huts in the background. My mother’s family went from Courland, in Latvia, to the Rhodesias, and my father’s from a shtetl in Lithuania to Johannesburg. I come at things as an African. Care for the environment—sustainability, we say now—was a necessity there. Robert’s family had a small farm and grew their food. Land erosion was an enormous problem that had involved them in soil conservation and organic farming. And we learned methods of sun protection and water retention in architecture school. But in America, when I said, ‘You’re facing the building the wrong way’, people in the office responded, ‘That’s why we have air conditioning’. Now they don’t say that. Here’s where the water runs down—you can see the lines over there, and the moss. Isn’t this moss lovely? The smell is beautiful. From that end, you see a symphony. Cherry blossoms and azaleas come out first, then dogwoods. Living things answer each other over time and make patterns in our garden through their relationships to sun, soil, and each other. In architecture, too, there are basic relationships. As beginners we learn simple ones: the size of a closet and where it should be in a bedroom, how bedrooms relate to bathrooms, and the living room to the dining room. We know these patterns—although for unconventional clients we might change them, combine rooms or leave the tub in the open, in general, clients want architects to maintain accepted patterns. It’s the same in cities. Forces of nature and society form patterns of settlement long before architects get there. Planners call the basic city-forming relationships ‘linkages’ or ‘city physics’. They’re functionalism for cities. Yet while we accept linkage relationships inside buildings and call ourselves functionalists, we run from them on the outside. Put the word ‘urban’ in the chapter title and architects go on to the next chapter. That’s where I think we lose our creativity, not to speak of our ability to satisfy people. And we have caused a lot of social harm. Urban renewal upsets of the ‘50s and ‘60s, the admonitions of Jane Jacobs, and the reasoning of Herbert Gans derive from what architects would not let themselves learn. When we first moved in to this house we got cold feet— What year was this? It was in 1972. How could we have been so crazy as to buy this old white elephant? The developer who intended to build houses on unbuilt land in the front couldn’t proceed until the old house was sold, so eventually his price came down to one we could afford. But when the deal was done, Bob cried, ‘How can we support all this?’ I was frantic; we had a 15-month-old son and a monster of a house, and I had a husband saying, ‘I don’t know what we’re doing here’. ‘Who can help?’ I pondered, ‘Who might like to?’ Architecture students, of course! We could pay them grad student hourly rates for their work if we also put them up and fed them, and if they saw their summer with us as a seminar. We went ahead on faith. Architecture students painted and mended the house, and pruned and weeded the grounds. We never failed to find a ‘handyperson’. Our attic floor has two small rooms and a bathroom. They stay there. ‘If you want friends to visit’, we say, ‘that’s fine’. And some help to mulch or clean the fishpond. The companionship of these young architects was wonderful for Jim, our son, as he grew up. And Bob and I, having worked with them most of our lives, loved and needed the company, too. We still do, and their architectural training makes them especially useful. They think holistically. In architecture, if you misstep on even one item, the building may fail. So we must research and design in the overall, like it or not. But urbanists from the social sciences see architects as totally intuitive—‘Oh, those artists!’ they say. Yet they’re less holistic than architects. And in deciding what to research, they too can be irresponsible and egotistical. Peter and Alison Smithson were starting their careers in London when I studied there. Although I could not be their student, I turned to them for advice. Peter said, ‘Go to Louis Kahn’. Kahn taught that while an artist may sculpt a car with square wheels to symbolise something, we architects must design them with wheels that work. It’s an interesting difference—perhaps the interesting difference—and if you believe no art can come from it, I think you’re wrong. In the ‘50s, city rebuilding was the main task, and architects with intelligence and talent saw urbanism as a focus for good and for architectural art. Now architects think you turned to urban planning because you weren’t a good designer. Do you want to see our frogs? Yes, definitely. Cheeky things—there’s a tonne of them. They don’t move when you go near. I’ve got too much algae in the pond, but if you take it out, it just grows back. We’ve got a vegetable garden over here, too; when I first came to this house, we got various tradespeople to come and work with us, and they’d always tell me about the old woman who lived here and how they always went off with a basket of tomatoes. She must have been overwhelmed with tomatoes. And, see, these are very old hedges that we’ve planted. What sort of conditions do tomato plants like? Lots of heat, lots of sun. We have done a little urban plan for this garden. It’s got a crossroads where you can take the wheelbarrow and turn it around. We have a whole lot of them down there and we’re going to make sure that they don’t fall on the floor. They’re looking happy, those tomatoes. They’re looking nice and fat. Yes, but we had other trees, which were really more climbing trees than these are. If you look down there, there’s a coach house, but these split-level ranchers were built later. This is a racially mixed suburb, integrated for idealistic reasons during Philadelphia’s post–World War II era of liberal Democrat government. That government had close ties with the University of Pennsylvania, where social planning originated. No one knows how good Penn’s planning school was! And it’s indirectly why Peter Smithson said, ‘Go there’. I was in both the planning and the architecture department. The planners were more interesting than the architects—Bob apart. He understood. His mother, Vanna, was a socialist and pacifist. She went to school hungry as a child and dropped out of school when her winter coat got too short. But before she left, a schoolteacher had noticed her brilliant young pupil. Vanna and Miss Caroll formed a lasting friendship and out-of-school teaching guided the young woman to become the poised beauty her husband-to-be saw at a ball at the Bellevue Hotel. Bob’s dad hoped to be an architect, but left school when his father died to help his mother run the family business, a retail fruit and produce market on South Street—the street we later helped to save. After World War I, Venturi Inc. became a purveyor to institutions and hotels, and it prospered. Bob went to private schools and Princeton and on to the American Academy in Rome. His was not too different a family story from mine, but their ascent was more vertical take-off than upward mobility. We met at my first Penn faculty meeting and, in the debate that day, found we were kindred spirits. To me, other Penn architects seemed aloof and rigid. I felt they were taking the worst, not the best, from ‘30s modernism, and I disliked the authoritarianism of their studios and juries. Planning school was different. In studio, we worked in teams and on one project, which contained many elements of design but also went beyond the physical to include social, economic, and environmental policy, research as well as design, and processes for bringing them all together. By spanning disciplines and working to link our analysis to our design, we hoped our plans would be functional and creative—even beautiful, but in their own way. My approach added a return to early modernism and concepts of ‘firmness, commodity, and delight’ to planning doctrines and methods. And as we critiqued modern architecture, Bob and I took it up in a new way. Form, for us, emerges complexly from more than function, and so does beauty. Forces make form, too, and letting ‘volunteer’ vegetation grow and following its patterns is one way. Another is ‘city physics’. Both bring richness and fun to the far-from-simple search for functionality and beauty. Architects design public places that the public doesn’t use, and sociologists say you can’t name a place ‘public’; the public makes it so when you satisfy their needs. But mapped analyses of our projects’ campus movement systems and activity patterns, and planned sequences of steps to pull them into a design, result in people moving along routes and using places as we had hoped. I suppose architects are often accused of thinking they’re making independent objects—the structure as this sovereign entity, without even necessarily a relationship to the structures that surround it. Absolutely, but I bang them on the head. I think lessons on where vegetation grows help. As small children, my mother took us walking in patches of veld remaining near us on the outskirts of Johannesburg. She showed us, as her governess showed her in Rhodesia, what lived in grass and sand. And like Miss Tobin, her governess, she coaxed musical notes from grasses and leaves and was always making things—with a walnut shell, a scrap of paper, glue, a pin, and a flag, she made a boat to float under a bridge and down a stream. As a beginning architecture student, I excavated for fossils in the wilderness during our July vacations. We camped, and our work was hard, but when I could I lay under a tree, looked up at foliage patterns and listened to veld sounds. My mother kept a pet monkey on a roof near her studio at Wits University. She had three brothers and no sisters and thought playing with girls was not what you did. You played with boys. She thought playing with the girls was boring? Yes, and so, of course, did I. As a student I would say, ‘I’d like to share my apartment with someone, but it’d have to be a man’. Then I found some women I liked, and they too wanted to play with the boys. Later we learned we were wrong: women must move up together or not at all. This group formed women’s lib. When Bob and I married, we each had years of experience—the last seven we’d spent in close collaboration, even teaching together. So when I joined the still-new office of Venturi, Scott Brown and Associates, we adapted our patterns of working together to fit professional routines and practices and to include the creativity of others. Design ideas were generated in many ways, mostly under our leadership, but also under that of others—and often, though not always, via ping-pong with a team. Many offices know the excitement of this unrecognised creative process. But critics in the profession said, ‘Well, she must be Bob’s business manager’ or, ‘She moved up by marrying the boss’. They couldn’t, and many still can’t, conceive that we were colleagues from the start; that I was inspiration to him and he to me, and that our practice was a joint work where design ideas came from both of us, and others. I read your piece ‘Sexism and the Star System’ about the way people have tended to assume your practice was peripheral to Bob’s. This has come up again recently, with the campaign out of Harvard to have your work recognised with a Pritzker. Do you think this has had an impact on your design? Do you think it made you tougher, or fiercer in your convictions somehow? No, I think it made me feel inadequate. It said, ‘You must be no good, they all say you’re no good’. It was debilitating. But as long as I was working with Bob and others, and our ideas were flowing, I felt happy. At Penn, I listened to Bob’s weekly theory lectures and loved his take on things that I loved, too. Feeling incredibly energised, I wanted to run out and do things. So did he. And through our collaboration, our themes crept into each other’s work. When I joined the practice, my abilities expanded Bob’s and broadened our scope. I remember his happiness at discovering I’m good at patterns—I’m an urbanist after all, and I photograph—because they’re necessary, but not quite his thing. And I can say, ‘On the other hand—’ which makes me a pain, but useful. For example, the opposite of collaboration is individual work, and a studio or office must have both. At certain points, people need to go away from the group, think on their own, and come back with something. Each one must offer something. And a project leader’s skills must include sensing when each is needed. All this makes for a full life. I adore practice; I adore teaching. I used to think, how could practice ever be as interesting? Yet I got to love it even more, and now it’s not open to me—no one is going to give us jobs. But everyone wants to do what you’re doing—come and talk with me. This is nice; I love it. And I love making collages of my slides to illustrate my points when I lecture. I call it curating, and I can talk to one slide for 20 minutes. I put together things that are evocative, heuristic, and interesting—but they must also be beautiful or no one will watch them. Sometimes I see two images together that look absolutely wonderful but make no point at all, but I can’t resist showing them, so I do. Then, suddenly, the reason they go together becomes apparent. This is my locus today for creativity, my venue for ‘making things’ as my mother taught me, and for finding beauty. It and writing are what I do now.

0 notes