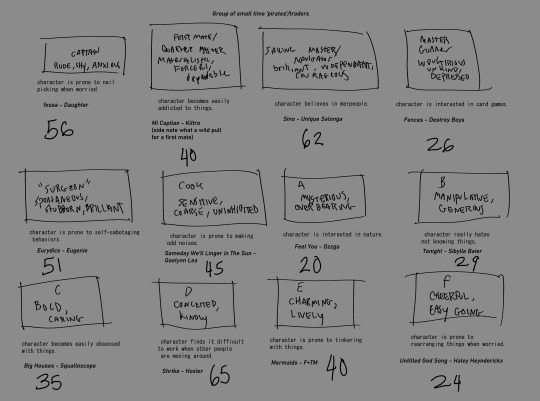

#a group of anti imperialists more realistically

Text

A somewhat randomly generated 'pirate' crew

The little references I started with - 2-3 random traits, a random quirk, and a song from my shuffled spotify likes and age... I'm not dead set on these since some don't really go together well but its a starting point!

#art#my art#digital art#character design#ocs#original characters#sketchbook#character creation#my pirate ocs#idk the ship name yet but once i do ill tag them as that#a group of anti imperialists more realistically#cant steal whats yours

589 notes

·

View notes

Text

The contradiction of airplanes in the sky

Whenever I’m in an airplane, I think of the contradiction that experience it embodies, and how it seems to be a metaphor for modern life. There’s so much wonder in flying thousands of miles into the sky, and yet we do it in a cramped, claustrophobic quarters that dilute or negate the magic. That’s what living today is like, is it not?

But of course, despite myself, being in an airplane always makes me feel wine-drunk with awe. When I flew back to Kansas last winter of 2021, I watched the sunset from the JFK airport and thought about the cycles of disappointment in love that I’d gone through that year, and thought about who I used to be, with my naive optimism and defensive arrogance protecting a shaky self image. At that time, I cringed to remember my past self.

But looking back now, I think of how I was just 22 and trying to figure it out. How much I love the boundless naive optimism that I carried with me throughout all the different selves I became, and how natural it seems that I would end up in Anakbayan – and how much that experience changed me. It affirmed my stance of joy as defiance.

There’s a word in tagalog that we use to refer to each other in the movement – “kasama”. It loosely translates to ‘together’, and ‘with you.’ What binds us in the movement is a current that’s deeper than political affinity – it’s shared vision, a shared history of “filipino and not-filipino.” The variable we share in common is that we’re all taking a gamble, staking our lives to a future that remains dark.

When I joined the movement, I was shocked to see people my age quoting Mao, identifying as radical anti-imperialists, and re-enacting guerilla theater of rebels. Up until then, I thought that organized resistance was a dead pipe dream of the 60s. To discover that it was real, even if only in the margins, shifted everything that I thought was possible.

I gained a specific kind of optimism that comes from seeing what revolution looks like in practice. It’s a feeling I haven’t found a language to quite articulate or describe or understand yet, though I think it has to do with resisting the state of psychological domination our culture is paralyzed by.

Of course, this spirit of optimism isn’t a constant. There are times I often look around and think, we really are just a small group of ragtag organizers. When I first joined, there would be times I would question the worth of our work in the larger scheme. It was easier to be a cynic than to dare to hope. Years after joining, I told my kasamas that this felt like the only sane space to me, and they all exchanged incredulous looks. And I understand, because actually, it does seem to feel that you have to be a bit insane to pursue the unrealistic and improbable.

To be radical is to change the parameters of what we can fight for. That was the most critical question in college, that I’ll always carry with me in my heart. What does it mean to be radical? Years later, as I’m writing this, I have an answer. To decide to eliminate the chair itself.

This work – the work of revolutionaries – goes against the dominant culture, which is why it’s so fucking difficult to do in isolation. It isn’t praised, or popular, or funded, or accepted in the mainstream, which makes it easy to question ourselves every step of the way – which can make us doubt ourselves – if we lose an inch of conviction. I admire my kasamas deeply for the courage it takes to ask for more than what’s realistic.

I think part of our optimism comes from – and is part of – the way we feel part of history. We share the understanding that the work we do in our lives goes beyond the brevity of our lifespan. There’s comfort knowing that even if change doesn’t happen in my lifetime, we’re building on the groundwork that generations before us have set, and generations after us will continue to build on, and whatever we accomplish, no matter how small, it won’t have been for nothing.

There are some who compare this kind of faith to the kind you find in organized religion, and that brings with it warnings of the dangers of idealizing any kind of ideology. The fear of being absorbed into an ideology is what made me initially hesitant to join a movement. But I’ve been part of a church before, and to me, there’s a clear distinction between political work and being a christian, even though they’re also familiar. It’s about committing to a value system and world view. The difference is that while I think political ideology offers a way to transform my values into action, by no means do I turn to it for either a blueprint or final answers.

There was a deep, fundamental change in my life finding the movement. I think my stance of optimism has somehow come from the gradual radicalization of my politics, and how that led me to recover hope and the spirit to fight. I found a home for my values, and an alternative to aspirations for material success and personal ambition that wasn’t just protecting my own individual happiness for the time I’m alive.

I think I write about this because I wonder what leads people to a movement. What radicalizes someone. Because I’m interested in what kind of spirit counters the fatalism of capitalist realism. A word for the opposite of loneliness. Because the words kasama and political home didn’t exist in my language a few years ago. For all the ways I’ve changed since accepting ‘revolutionary’. My shifting perceptions of the words “radical” and “revolution”. Paradigms upended. Wondering about the common variable behind the emotions of joy, agency, self-determination, the willingness to struggle, optimism, hope, faith, these supercharged euphorias. Courage and strength, all entertwined with love and rage and compassion and kindness. The seedling of an understanding that if we want a revolution, we have to understand how these emotions all can be transformed and channeled into revolution. Into people power. There’s an answer, somewhere, in the optimism that comes from seeing other people care and believe, just as much, in what used to seem to be an untenable fantasy: revolution. Genuine change within our lifetime. That what we dream of is not to much to ask for. But we have to start with naming what we are fighting against, and what we are dreaming of. James and I joke, without really saying it, that the answer is revolution. What is to be done with this world? Where are we going?

I’ve been thinking about the premise of my conclusion in college – how the word utopia is an ancient Greek pun on “ou-topis”, meaning “no place”, and “eu-topos”, meaning “good place”. It was originally coined by Thomas More, and implies that a perfect political state cannot actually exist. I have no masterplan for saving the world. I don’t have the details of what an ideal world would look like. But we always ask each other, what do you want for your community? What are you fighting for? As if these questions are worth asking, are serious questions to consider, and not frivolous at all. I do think we are entirely capable of asking for a different present, of dreaming for the way that we can live right now.

Hannah Arendt believed, above all, that if we could say, I don’t want to live this way–and that if we projected these longings into the world–we could work to address the lonelinesses we inflict on others; the isolation that drives us to destruction and our desire to dominate. In her biography of Lessing, you can find Lessing’s notion of love threading throughout her work; the kind of love that simply says “I want you to be”. She believed that in order to rebuild cultures from the politics of exclusion and division, ones that make truth and justice meaningful in the world, communication and changes in modes of thought had to happen between two people. She believed we could imagine only by understanding, by living and knowing together.

___________

Somewhere outside the invisible net cradling earth, satellites are spinning in the yawning empty black and the pulse of cities is so far away. People are dying from a pandemic, in the antiseptic halls of hospitals. In future dystopias, a love song waltzes from an underground bunker.

It’s spring now, and I find myself caught in the still warmth of an evening where I have absolutely nowhere to go. The busyness of the day fading to twilight, bright shadows thrown up against the skyscrapers of Manhattan. It’s an alien feeling, the relief to realize I have no obligations. I stand for a moment in Brooklyn as bodies rush past me, looking at the sky, looking at people, a still point in a crowded intersection, feeling for the first time in a long time that I longer have to be anywhere. A breeze on the back of my neck, the air tasting like lemon and sticky asphalt, and no one knows who I am.

On my way to Coney Island, I accidentally dislocate the chain from the gears with my shoulder, and so I stop in the middle of the sidewalk to lock it back in place, wipe the grease from my fingers onto my backpack. Beyond the language of nuclear radiation and retreating shorelines, there’s a place where we go on and survive.

despite how difficult it is, how widespread futility and cynicism are, we are all suffering together and finding joy somehow, and there’s comfort in that.

0 notes

Text

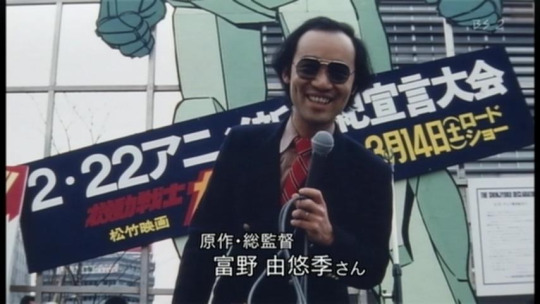

Animation Night 94: ‘The New Anime Century’

Apologies for the very late start today. I’ve not been at all functional. I understand that most eyes are on Ukraine right now. Nevertheless, it is important to me to keep up the streak of Animation Nights, so an Animation Night there shall be.

Since it’s so late, and I’m not in the best sorts, I’m going to lean on a previous writeup; we’ll be looking back at the misty origins of the vast Gundam franchise, and a curious set of historical events.

Today is 24th of February, two days off from February 22. Back in 1981, February 22 was the premiere of the film adaptation of Mobile Suit Gundam; at first an unsuccessful television show that tried to inject elements of ‘realist’ sci-fi war drama, which became a cultural phenomenon on the back of ‘gunpla’ model kits, and then, a symbol of the changing audience of animation in Japan - something which Tomino would claim as a ‘New Anime Century’ (anime shinseiki sengen) at the occasion of the film’s premiere.

Normally I would launch right into the history, but I feel like the context means I ought to say at least something about how this all connects to our time. Because a war has just considerably escalated in Ukraine, joining the ongoing wars in e.g. Syria and Yemen, as various imperialisms vie for dominance and various groups of people of myriad ideologies cast in with this or that faction that might protect them, or get caught in the fighting of others, like the Saudi naval blockade and resulting famine. “What the hell you even do” is a question we continually face, especially when we are so powerless - something acutely experienced by e.g. the Ukrainian anarchists interviewed here, for whom the choices not ‘what to tweet’ but whether to pick up weapons, and if so, how to avoid their tiny movement getting subsumed into a nationalist project.

Understanding a war at the time it’s taking place is very difficult; in the years following, it falls to artists of various kinds to end up defining the social meaning of that war, and the whole sorry spectacle of war in general. Is that a good thing? Who the fuck knows. But it happens, regardless.

So, for example, thanks to novels and memoirs like All Quiet on the Western Front and Poilu, famous poems, and various histories (an art form itself) constructed by sifting through the records and propaganda, the gigantic act of human sacrifice that broke the old imperialist system and opened the ‘bloody twentieth century’ can be turned into a story that we can at least pretend we comprehend in some way as ‘World War I’. (For good or ill! The Italian futurists and, later, Nazi propagandists turned their artistic efforts towards telling a story to further or repeating that war. And of course, during the war itself, all sides called on their artists and reporters to tell stories that would maintain the supply of bodies and shells to combine alchemically into ‘political power’ and corpses.)

In the decades after whatever temporary peace is found, the art ends up talking not about our direct experience of living through a war (an experience that is traumatic even far from the actual fighting), but the images of it we receive in art. The Nazis, for example go from actual people who you or your audience may have physically fought or lived under or fled, whose genocides were only recently exposed, to cartoon villains or even edgy sex symbols. The survivors gradually die and romantic narratives take over from people to whom that war was a story. And yet, the experience of these later generations living in the shadow of all the millions of empty deaths is still something that will - inevitably! - be expressed in art.

(this is from 08th MS Team so the animation is a bit more modern than what we’ll see today - I don’t really have time to scour the gif searcher for OG gundam clips!)

So, Gundam. Famously, Tomino is an ‘anti-war’ director. But whether an ‘anti-war’ film is even possible has often been called into question. Certainly, you can present images of senseless death and suffering - but the cult of the soldier loves the struggles borne by its ‘heroes’ for the sake of the nation. (The logic of sacrifice transfers the value of the thing sacrificed; kill a prize cow for a god, and you are declaring that to you, such food and wealth is less important than the god. Kill a million soldiers in ‘service’ of a nation, and the psychic power of the nation is strengthened, not weakened, by the value of a million human lives.)

It is easy to say “war may be an awful thing, but this time, we must fight” - and to recognise the logic of violent domination and coercion that doesn’t care for principle. And so, those who wish to start or sustain a war have long, long ago learned that they need to make a plausible-enough case that it is ‘justified’ to maintain their supply of bodies, and have developed very sophisticated ways of telling that story.

Mecha anime, and Gundam in particular, inherits a curious relation to war in general and Japanese history in particular (their failed imperial ambitions and the aftermath of near complete destruction by war, their relationship to the USA in the Cold War, and the question of the restrictions placed on the JSDF, much to the resentment of far-right nationalists).

It depends, fundamentally, on lavishly elaborate depictions of military equipment - before it narrowed to ‘giant humanoid robots’, the term ‘mecha’ simply meant machinery in general, and the visual language of giant robots (especially in Gundam’s ‘real robot’ subgenre) takes a lot of cues from jets and tanks and other such machines. (Last time around, we talked about how the first ‘super robot’ manga, Tetsujin 28-go, imagines a secret WWII weapon in the hands of a child.) Mecha have many meanings, but an inarguably important one is that we are captivated by the image of precisely engineered killing machines; for much the same reason, people adore guns even if they have no intention of killing anybody with them. I don’t think this enables war, inherently - it is a reality of our experience of a violent world that is being reflected truthfully in our art.

And yet, for all that, Tomino wished to tell specifically a tragic story about war; calling attention to the humanity of the enemies, and filling his story with senseless death and grief proper to the subject matter, which was a significant break. How strongly and coherently this theme has been expressed and developed varied through the franchise, which was primarily an instrument to move gunpla models and faced many constraints, but it’s a stance he held fast to pretty much throughout. This productive contradiction has fuelled several subsequent decades of robot anime; in the 90s, Anno’s ‘New Gospel’ of Evangelion would take mecha into a much more psychological direction, but it’s always been in part about war.

And how animation should treat the matter of war (as a subset of film in general) was at the time becoming a significant subject of contention. A year after Gundam‘s film premiere would follow the conflict over the film Future War 198X in which anti-war, Soviet-sympathetic trade unionists vehemently protested what they saw as a warmongering film.

To say more is really more than I have time to talk about tonight; let’s press on to the event in question that frames tonight’s screening: the 1981 release of the Gundam theatrical trilogy and the ‘New Anime Century’. (I talked about Tomino’s career leading up to Gundam last time so go back there for that!)

As this page recounts, the original Gundam TV anime was cancelled, but the series became increasingly popular off the strength of gunpla kits, eventually resulting in a recut of the series into three theatrical films with a great deal of ceremony. The turnout on the day was unexpectedly huge (in part due to the temptation of 10,000 free Gundam posters), and Tomino became afraid that a riot might break out:

By the morning of the 22nd February, there were 2,000 fans at the east exit to Shinjuku station. Tomino wryly observed that a TV director’s life was often lived hand-to-mouth, worrying about little more than the next meal, but here, outside a cinema for one of anime’s first big grown-up movie events, we were seeing the true power of television – its ability to attract an exponentially larger number of viewers. TV people had always been excluded from the movie world – now, suddenly, he saw that they had taken it over.

The posters were gone by 10am. By midday, Tomino estimated the numbers were pushing 15,000, which threatened to turn the event into a riot. Ever since the Anpo Protests over the controversial US-Japan Security Treaty (an event later referenced in the opening unrest of Akira), “public demonstrations” had been illegal around Shinjuku station. Enough Gundam fans had now gathered to risk attracting police attention, and Tomino fretted that an injury in the crowd could attract exactly the wrong kind of media attention. His “new anime century” risked dying before it could even begin, with future events shut down as too dangerous.

So, Tomino made an address to the crowd, like a politician speaking at a rally, with little preparation. His statement was... a curious and still rather boastful one:

“Sorry, but you are dummies,” he shouted, presumably in reference to the number of bodies needed to create a noticeable crowd. But then again, you never knew with Tomino. “We gathered you here to make a statement, to make all the grown-ups wonder what so many young people want to say. And in fact, the statement we really want to make is not about Gundam at all! But Gundam is the name that has gathered you youngsters here today. We need the grown-ups to wonder what this Gundam is all about. We need them to understand what young, modern people, teenagers, are seriously thinking about, and grasp that by seeing Gundam for themselves, even once.”

His awkward address, and official declaration of the ‘New Century’, would be repeated by two younger anime workers:

Tomino spoke from the stage, but doubted anyone heard him. At 40 years of age, he already belonged to a different generation. Ultimately, the proclamation’s official delivery was read out by “the kids” themselves, two young students, who were both already intimately involved in Tomino’s new era of anime: Mamoru Nagano, the future creator of Five Star Stories, and Maria Kawamura, already a voice actress in several Tomino productions, fated to become the iconic Jung Freud of Gunbuster.

Both in cosplay at the time, the two would eventually marry.

Much later, this event would be narrativised as ‘the day anime changed’ - though this seems like far too neat a narrative and many of the elements popularised by Gundam had been in the works throughout the 70s. Still, it did correspond to a turning point: the 80s soon saw the rise of the OVA market and rapid transformation of animation from purely a children’s medium to one capable of attempting more challenging stories - or serving the very specific tastes of adult otaku. Anime directly addressing war would become increasingly emotionally sophisticated - subsequently we would see films like Barefoot Gen (Animation Night 26), Grave of the Fireflies and In This Corner of the World as the realist movement developed. It would be absurd to ascribe all this to the influence of Gundam (as much as it would surely flatter Tomino) but the three Gundam films do stand at a pretty important point in that big historical flow.

I won’t say anymore, because it’s 11pm and I would like to start Animation Night on Thursday, even if we’ll probably have to watch the last film tomorrow. We’ll be starting the screening very shortly, but if you feel like dropping in at any point, I’ll happily catch you up. So please, head over to https://www.twitch.tv/canmom!

#animation night#god idek if i'm even approaching addressing these subjects with the level of care required#but also this question is very important to me as an artist who wants to speak truthfully so... i guess i gotta make a start somehow

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ilvermorny

Given with how sometimes being a wizard is not a hereditary thing, I find it very hard to believe that you can just go without racism. It is something so ingrained into our society. Even if pureblood wizards never discriminated based on race, not all wizards going to Ilvermorny would be a part of that kind of culture. I’m pretty sure most would be racist. Besides that I think, realistically, all the white wizards would be the first to come together. And the Indigenous wizards would definitely practice magic differently from the white wizards, creating another barrier between the two groups. While it is likely for two very different groups of people to coexist, history has shown that it is more likely for the colonizing group to try and overtake the other. And while the founder of Ilvermorny was not racist and actually welcomed Indigenous people into her school I think the opposite would be more popular. I read somewhere how there’s a theory that there were a small group of settlers who ended up integrating and coexisting with the tribe that was already living there. And that is literally just a theory, but we have our whole history showing how discriminatory white people were and still are to Indigenous people. I honestly hate that Ilvermorny is the first wizarding school in America, as if the Indigenous people of the area didn’t already have a way of life or as if they needed to be colonized or as if things didn’t really start till the white heros came in.

Anyways, having Ilvermorny’s history and school be different to hogwarts allows you to explore many different things. Something which the fantastic beast movies don’t really allow for. The first movie takes place in the 1920s and yet the person in charge in the American wizarding world is a black woman, which let’s be honest she’d definitely be discriminated against. The wizarding world in the US is probably more integrated with the no-maj world. And like with the Indigenous people, the African people forced over here most definitely saw/practiced magic in a very different way, and I don’t think the European wizards would be too fond of it. So what I am saying is that you probably have three (or more because each Native American tribe would have definitely practised magic differently) very different ways of practicing magic that can over time slowly come together. This allows you to explore many different stories, which could be driven by black and Indigenous people. Even though this is a made up story I still think it is problematic to whitewash it, because it is something white people have been doing for many years and still continue to do. You see how this is done with MLK jr’s image. During his time he didn’t just advocate for a peaceful movement, but was anti-imperialist and a dedicated democratic socialists. He was such a radical figure, who would definitely be considered radical for today’s standards and yet he was whitewashed to the point where liberal and moderate democrats and even republicans can say that they agree with him. And republicans even use his quotes and image to shut up blm supporters. But we know damn well they wouldn’t agree with him if he were alive today. After his death he was not popular with 2/3 OF THE COUNTRY!! We only really hear about him speaking of peace, but he was a radical brilliant man was outspoken about economic inequality. So, back to what I was saying before, if we accept this whitewashed version of Ilvermorny and just magic in the US in general, then you leave out many other stories.

If you got through all this, thank you.

This was just a critique of wizarding world? in the US.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Remembering the Lesbians in Lesbian/Gay Liberation

Remembering the Lesbians in Lesbian/Gay Liberation

By Ann Menasche

Under patriarchy, lesbians are not supposed to exist. Women - "normal" women at least - are supposed to need men to be complete, for love, for sex, for economic survival, for family, for legitimacy. In such a world, there is no place for lesbians; if a few manage to exist, they are seen as freaks or pariahs. Not surprising that we rarely appear in history or when we are named at all, we are portrayed as lonely spinsters pining after some man. (Remember the lies told about 19th century poet Emily Dickenson, who had a lifelong passionate relationship with her sister-in-law.)

In the mid-to-late 20th century, ideas of traditional womanhood began to be challenged as women as a sex gained increased independence. By the height of the Second Wave of feminism in the late 60s and 70s, lesbians had begun to emerge from the shadows and establish themselves among the leadership of the newly emerged Feminist and Lesbian and Gay Liberation Movements. And as the synergy of Lesbian/Gay Liberation and Radical Feminism freed more women to be able to pursue a lesbian life, a vibrant culture of Lesbian Feminism emerged. That culture produced socially conscious music, poetry, books, publishing houses, newspapers, feminist theatre, coffee houses, and festivals run by and for women that inspired and sustained us and helped fuel the political activism of the time. And in this environment we began to rediscover the lesbians that came before us. We no longer felt so alone.

But times have changed again and lesbians are being rendered invisible once more. Even the contributions lesbians made to the Movement for Lesbian and Gay Liberation are being forgotten. Many factors have contributed to this disappearing of lesbians from history, from our public consciousness, and often from ourselves and each other. While lesbians have won some mainstream acceptance through marriage equality, the accumulated losses have begun to be greater than the gains. Hard economic times, a conservative political climate, the growth and increased power of the Christian fundamentalist Right and a growing backlash against feminism have conspired to make lesbian existence harder once more. Independent lesbian culture has been destroyed. Even the lesbian bars that, despite their flaws, provided a place to meet and find community with other lesbians are now gone. In their place is a sense of utter isolation and despair among many lesbians. And there is often no place to turn for support except perhaps online forums.

Moreover, though the illusion that we've already won our rights is widespread, the reality is quite different. Lesbians in the United States can still lose their jobs, be disowned by their parents, lose custody of their children, and be raped or murdered for loving other women. Anti-lesbian prejudice is everywhere.

One of the most destructive influences on lesbians, which is erasing us from history and undermining the possibility of lesbian existence in the present, is gender identity ideology. As this ideology has become increasingly predominant, overwhelming our lesbian/gay communities and incorporating itself into law and culture, lesbians have felt ourselves surrounded on all sides. We are being pressured and guilt-tripped on the one hand to accept men calling themselves women into our communities and our bedrooms. At the same time, rebellious young girls with same-sex feelings, and lesbian adults are being convinced in growing numbers they are really "men" and are being coerced or swayed into "transitioning." As women’s liberation no longer appears to be a realistic goal, some of this vulnerability to the forces of transgenderism and extreme body modification may be summed up by the phrase “if you can’t beat them, join them.” How else escape the violent heavy hand of misogyny on our bodies and lives but to pass as male?

Without question, Lesbians have become extremely marginalized within the modern LGBTQ+ "alphabet soup" - the corporatized stepchild of the Lesbian and Gay Liberation Movement. LGBT centers in the name of trans-inclusion, refuse to provide space for lesbians to even meet together outside of the presence of males. We are not welcome at Pride and even the Dyke March has been taken from us by “lesbians” with male genitalia and their supporters. And as lesbians have been virtually disappeared, so has the role we played in the struggles that came before us been disappeared as well.

Our lesbian foremothers are once again gone from the history books, or are posthumously "transitioned," described as "queer," or treated merely as a footnote. But lesbians fueled the Lesbian and Gay Liberation Movement from its start. It would not have happened without us. And it is time to give credit where credit is due.

The Stonewall Rebellion on June 28, 1969 was not led by individuals identifying as transgender. Transgenderism barely existed at that time even as a concept. What existed was large numbers of lesbians and gay men, some of whom cross dressed or dressed in drag, but did not thereby deny either their sex or their homosexuality. Drag queens and butch lesbians were among those who found community at the Stonewall Inn in New York, a bar owned and operated by the mafia but one of the few places that same sex couples could dance together. Police raids were commonplace but that historic night as police dragged patrons out of the bar and beat them, one butch lesbian, Storme DeLaverie, decided she had had enough. When a police officer shoved her and called her a "faggot", she punched him in the face. Four officers assaulted her and one hit her on the head with a billy club. Bleeding from the head, and dragged toward the police van, she yelled "Why don't you guys do something?" The rebellion was on and lasted six nights. Lesbian and Gay Liberation was born.

Martha Shelley, a lesbian with strong left-wing politics, had passed by the Stonewall on the fateful night but thought she was seeing an anti-war protest. She had no idea that the people throwing rocks at the cops were gay. When she realized what she had missed, she contacted the Daughters of Bilitis and the Mattichine Society and made a proposal for them to jointly sponsor a protest march. On July 27, 1969, 200 lesbians and gays marched in Greenwich Village, in what was to become the world’s first Gay Pride Parade. The organizing committee formed itself into the Gay Liberation Front, a revolutionary group that demanded not assimilation but a complete overhaul of the patriarchal, racist, imperialist system. A new movement was launched, initiated by a lesbian.

Almost a decade later in 1978 in San Francisco another lesbian was the central leader in the successful movement to defend Lesbian and Gay Rights then under attack. This was the struggle against the attempt by Christian fundamentalists to pass the Briggs Initiative, a proposition that would have banned gay teachers and all supporters of Lesbian/Gay Rights in the schools. Though everyone knows about Harvey Milk, many giving him credit for the defeat of the Briggs Initiative, it was actually Nancy Elnor, a lesbian-feminist and socialist, someone virtually no one has heard of, who was far more responsible for that victory. I knew Nancy personally and worked together with her in the Bay Area Coalition against the Briggs Initiative. We were on and off again lovers, our personal interaction often stormy, but my admiration for her never waned.

Nancy worked long hours, doing amazing grassroots organizing work always accompanied by her German Shepherd "Bianca" and put together a mass movement that brought out tens of thousands into the streets against Briggs. She brought in organized labor and every progressive organization in San Francisco to join the cause, and chaired packed meetings of activists. The Coalition under her leadership, organized a televised debate between Milk and Sally Gearhart on the one side and Briggs and one of his cohorts on the other. A thousand people watched the debate on a big screen in a local high school auditorium. Nancy's in-the-streets movement building done through distributing thousands of flyers, making hundreds of phone calls, and attending dozens of meetings (there was no Internet) set an example for the whole state, helped change the political climate, and put us on the path to victory. Nancy died young but I'll never forget her.

As many lesbians celebrate Pride with varying degrees of ambivalence or else consciously ignore the festivities as no longer speaking to us, it is important to remember and celebrate the heroic leadership of our lesbian foremothers who changed history. If we did it once, we can do it again.

Read the full article

#BayAreaCoalition#BriggsInitiative#Christianfundamentalists#DaughtersofBilitis#DykeMarch#GayLiberationFront#GayPrideParade#GreenwichVillage#HarveyMilk#Lesbian/GayLiberation#MarthaShelley#MattichineSociety#NancyElnor#radicalfeminism#SallyGearhart#StonewallInn#StonewallRebellion#StormeDeLaverie#transgenderism

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

1919: When the Bolsheviks Turned on the Workers—Looking Back on the Putilov and Astrakhan Strikes, One Hundred Years Later

One hundred years ago in Russia, thousands of workers were on strike in the city of Astrakhan and at the Putilov factory in Petrograd, the capital of the revolution. Strikes at the Putilov factory had been one of the principal sparks that set off the February Revolution in 1917, ending the tsarist regime. Now, the bosses were party bureaucrats, and the workers were striking against a socialist government. How would [the dictatorship of the proletariat respond?

Following up on our book about the Bolshevik seizure of power, The Russian Counterrevolution, we look back a hundred years to observe the anniversary of the Bolshevik slaughter of the Putilov factory workers who had helped to bring them to power. Today, when many people who did not live through actually existing socialism are propagating a sanitized version of events, it is essential to understand that the Bolsheviks meted out some of their bloodiest repression not to capitalist counterrevolutionaries, but to striking workers, anarchists, and fellow socialists. Those who do not remember the past are condemned to repeat it.

If you find any of this difficult to believe, please, by all means, check our citations, consult the bibliography at the end, and investigate for yourself.

A note on the artwork: the artist, Ivan Vladimirov, was a realist painter who participated in the Russian Revolution, joining the Petrograd militia after the toppling of Tsar Nicholas II. He used a style of documentary realism to portray scenes from the Revolution and Civil War. Afterwards, he continued to work as an artist in good standing with the Soviet Union—such good standing that he lived into the 1940s and died of natural causes!—although he was compelled to shift to making fluff pieces lauding Soviet military triumphs and social harmony.

Bolshevik Realism

In March 1919, the Bolsheviks had uncontested power over the Russian state, but the revolution was slipping from their grasp. As self-styled pragmatists and realists, they believed that revolution had to be dictated from above by experts. Who can better understand the needs of the peasants and the proper means for communalizing the land and sharing the harvest than a revolutionary bureaucrat in an office in the city? And who knows more about the plight of the factory workers than a party official who worked in a factory once and now spends all his time going to committee meetings and interpreting the dictates of the Fathers of the Proletariat, men like Lenin, Trotsky, Kamenev, Sokolnikov, and Zinoviev who never worked in a factory or toiled in the fields in their lives?1 And who better to protect the interests of the soldiers than the political commissar who stands at the back of the line during an offensive, pistol in hand, ready to shoot anyone who does not charge into enemy fire?2

Bolshevik realism made it clear that the only way to execute a real revolution was to take over the state, make it even stronger, and use it to stamp out all their enemies—who were, by definition, counterrevolutionaries. But the counterrevolutionaries must have had secret schools in every town and village, because by 1919 more and more people were joining their ranks, especially peasants, workers, and soldiers.

The “dictatorship of the proletariat” would have to kill a whole lot of proletarians. Not everyone could make it to the Promised Land.

1919: Russians searching for food in the garbage during the lean times of the Civil War.

Enemies, Enemies Everywhere

The dastardly anarchists had corrupted the age-old revolutionary slogan, the liberation of the workers is the task of the political commissars—get back to work, it’s under control. They had replaced it with a dangerous revisionist lie—“the liberation of the workers is the task of the workers themselves”—and more and more people had come to believe this lie. In April 1918, the Bolsheviks unleashed a terror against the anarchists, who were becoming especially strong in Moscow. In September, they instituted a general Red Terror against all their former allies, killing over 10,000 in the first two months and implementing the gulag system.

They also had to turn their guns against the peasants, who were in open rebellion against the policy of “war communism” by which the Red Army and party bureaucrats could steal whatever food, livestock, and supplies from the peasants they saw fit.3 Evidently, the uneducated peasants didn’t have the vocabulary to understand that this theft was a “requisitioning,” that their starvation was a form of “communism,” and that it was being supervised by incorruptible men who had their best interests at heart. In August 1918, Lenin directed the Cheka and the Red Army to carry out mass executions in Penza and Nizhniy Novgorod to put an end to the protests. But dissent only spread, and the peasants gave up on protesting in order to arm themselves and fight back. Many formed “Green Armies,” localized peasant detachments that often fought against both the White and the Red Armies.

There was also a shortage of realism in the Red Army. Arguably, the most effective fighting units in the war against the tsarists and the capitalists of the White Army were the localized, volunteer detachments that elected and recalled their own officers; granted no special privileges to officers; defined their goals, general strategies, and organizational principles in assemblies; relied on the goodwill of local soviets to supply them; and were intimately familiar with the terrain they operated on. Such detachments included Marusya’s Free Combat Druzhina, the Revolutionary Insurgent Army, the Dvinsk Regiment, and the Anarchist Federation of the Altai. Few other detachments were able to inflict critical defeats on tsarist forces even when they were overwhelmingly outnumbered and outgunned.4 The fact that the combatants fought for a cause they believed in, were led by strategists elected on account of their abilities, and were wholeheartedly supported by the local peasants and workers enabled them to use the terrain to their advantage, fight more bravely than their opponents, innovate creative and intelligent strategies in response to developing circumstances, and transition between guerrilla and conventional warfare in a way that confounded the enemy. Such groups were instrumental in defeating General Denikin, Admiral Kolchak, and Baron Wrangel, ending the three major White offensives—not to mention capturing Moscow at the beginning of the October Revolution.

But all of these groups suffered a fatal defect. These fighters often prioritized listening to local peasants and workers and their own common soldiers over the wise dictates of the Fathers of the Proletariat emanating from the capital. Even worse, sometimes they did hear those dictates, yet still disobeyed them. And when the Party leaders, in their infinite wisdom, decided that it was necessary to massacre peasants or workers for the sake of the revolution, the detachments led by those very peasants and workers simply weren’t up to the task.

1917: Eating a dead horse.

In order to increase the efficiency of the Red Army, the wise masters of the Bolshevik Party decided to take lessons from the great militarists of history, starting with the Tsarist army. By June 1918, they had abolished all the anti-realist policies that revolutionaries had wrongheadedly introduced into the Red Army: they discontinued the election of officers by the soldiers who would serve under them, reinstituted aristocratic privileges and pay grades for officers, recruited former Tsarist officers accustomed to those privileges, and brought in political commissars to spy on the soldiers and root out any incorrect thinking. After all, rebellious idealist soldiers had toppled one regime in 1917—and without a sufficient dose of realism, they might well topple another.

The Bolsheviks had also learned from imperialist armies throughout history that sent soldiers from one end of the empire to fight rebels at the other end of the empire. This was a sentimental kindness on the part of the Bolsheviks. Psychologically, it was much easier for Korean-speaking soldiers to avoid fraternizing with Ukrainian peasants and workers near Kharkiv—and on occasion to massacre them—and for Ukrainian-speaking soldiers to avoid fraternizing with Korean peasants and workers near Vladivostok (and occasionally to massacre them, too). This strategic practice also helped keep soldiers from getting lost. A Red Army soldier from Ukraine, fighting counterrevolutionaries in Irkutsk, would be hard-pressed to obtain support from locals or find his way home without leave. That ensured that he would know to stay with his regiment rather than deserting in a fit of anti-realism. And if he did get lost, a blond, round-eyed Ukrainian would be easy to find among the locals, who could return him to the proper authorities. Good organization: this is how a successful revolution is waged!

Yet the soldiers of the Red Army weren’t educated enough to understand. A million desertions took place in a single year. Many Red Army detachments took their weapons and joined the peasants who were forming independent Green Armies. Later, huge groups would join Makhno, who was naïvely defeating the Whites without installing a dictatorship of his own. So the Bolsheviks had to be cleverer than their tsarist and imperialist mentors. They shot tens of thousands of deserters, but this age-old tactic wasn’t enough. In a burst of inspired realism, they improvised a new tactic: taking the family members of soldiers hostage, and executing the family members if deserters did not turn themselves in to be shot.5

Propaganda poster: “Deserter, I extend my hand to you. You are as much a destroyer of the Worker-Peasant State as I, a Capitalist!”

While so many of the Red Army’s bullets were ending up in the bodies of Red Army soldiers or in the uneducated brains of anti-realist peasants, too few were being fired at the White Army—and the White Army was growing, threatening the revolution on every side. The Red Army was slowly pushing back the Northern Russian Expedition of British and US troops on the Northern Dvina front, but intense fighting over the winter had failed to dislodge General Denikin from the Donbass area of eastern Ukraine. Meanwhile, a French expeditionary force had landed in Odessa, the White Army had cemented its hold on the Caucasus, and at the beginning of March, Admiral Kolchak had begun a general offensive on the eastern front, quickly capturing Ufa and continuing to gain ground.

The anarchist Black Army held the line in southern Ukraine, but their clever Bolshevik allies were starving them of weapons and ammunition, hoping the White Army would finish them off. This was an effective economization of resources on the part of the Fathers of the Proletariat. They would not have to spend time debating anarchists or making propaganda against them if the anarchists were all dead, and it was much easier to present themselves as the alternative to the confused tsarists and liberals of the White Army than it was to debate the anarchists, with their insidious lies about people being capable of liberating themselves.

The stratagem of denying resources to the Black Army was to backfire in summer 1919. After Denikin broke through the lines, he advanced so far against a helpless Trotsky that he threatened Moscow, and only a resounding success by anarchists at the Battle of Peregenovka in September 1919 cut off White supply lines, ultimately forcing Denikin to retreat. But after all, that was why the Bolsheviks had allies: it was easier not to put all the people they wanted to kill on their “enemies” list all at once, in hopes that they would first kill each other in ways that would be advantageous to the Bolsheviks.

1920: Bolshevik propaganda in the village.

Worker Resistance to the Soviet State

Let’s rewind to early 1919, when, facing so much resistance, the Bolsheviks needed more allies. They had legalized the Mensheviks after a few months of the Terror, and gotten the various anarchist detachments to focus their energies on fighting the Whites, but they still needed more support. After half a year of killing and imprisoning members of the Socialist-Revolutionary Party (SRs), the Bolsheviks legalized the SRs; to be fair, the previous year, the SRs had tried killing and imprisoning the Bolsheviks, after the Bolsheviks had tried to monopolize all the instruments that would allow them to kill and imprison people. The Bolsheviks had won those monopolies now, but a revolution can’t defend itself if too many of the participants are dead or in prison. They still needed help getting the common people in line working for and fighting for the Bolsheviks. The SRs had been good propagandists and considerably more popular than the Bolsheviks. Besides, it was easier to keep the SRs under their thumb when they were out in the open, with public offices in Moscow, than when they were operating underground.

The SRs decided to trust the Bolsheviks, hoping that they could regain control of the soviets or win over other revolutionary forces. But once they came out of hiding, the Cheka began periodically arresting the SR leadership, accusing them of conspiracy, and hustling them off to the gulags. The organization never regained the strength to oppose the Bolsheviks. Meanwhile, the legalization of the SRs and Mensheviks had reduced the number of enemies the Communists had to fight, and set more forces to work putting out propaganda in favor of the revolution.

The Bolsheviks still had plenty of problems. If it wasn’t bad enough that so many peasants and soldiers were rebelling, the factory workers also began to rebel. In the city of Astrakhan, the workers went on strike. Even worse, many Red Army soldiers joined them, and similar strikes began to spread in the cities of Orel, Tver, Tula, and Ivanovo. Then strikes broke out at the giant Putilov factory in Petrograd, the capital of the revolution.

The Putilov factory had built rolling stock and other products for the railways, before branching out into artillery and armaments for the military. Later, they would also manufacture the tractors that would become essential to the industrialization of Russian agriculture, after Lenin ordained the transition from war communism to the “state capitalism” of the New Economic Policy. A strike at this factory was especially embarrassing for the Bolsheviks, because the Putilov factory had been one of the origin points of the revolution. The revolution of February 1917 had sprung from four groups: rebellious military units at the front, women protesting government food rationing, sailors stationed at Kronstadt and Petrograd, and striking workers at the Putilov factory. Strikes at the Putilov factory had also been one of the sparks that caused the 1905 Revolution.

The Bolsheviks had already dealt with the Dvinsk Regiment—heroes of the revolution and a symbol of the refusal of soldiers to fight in an imperialist war—by assassinating their commander, Grachov, and disbanding the regiment. They had managed to do this quietly and out of the public eye. Later, in 1921, they would explain that in the course of the revolution, the Kronstadt sailors had somehow gone from being the staunchest defenders of revolution to become petty bourgeois individualists infiltrated by White agents. No one really believed Trotsky when he said this, but it didn’t matter.6 What was really at stake was not truth, but power; the Bolsheviks had already crushed all their other enemies, and they resolved questions about the politics of the Kronstadt sailors not by presenting facts, but by slaughtering them, as well.

But the crushing of Kronstadt was still two years in the future. In March 1919, the Bolsheviks still had plenty of enemies, and everyone was watching. The Putilov workers had some simple demands: increased food rations, as they were starving to death; freedom of the press; an end to the Red Terror; and the elimination of privileges for Communist Party members.7 What would the Bolsheviks do? Was it possible to have a revolution without starving the workers, shutting down critical newspapers, disappearing revolutionaries of other tendencies, and elevating Party members as a new aristocracy?

1920: Seeking an escaped kulak.

The Bolshevik Response

What a silly question! The Bolsheviks were realists, and their strategy relied on making the revolution by gaining control of the State. The State was the Revolution, as long as it was a Bolshevik State. They couldn’t make the State stronger without eliminating their rivals, squeezing the workers and peasants for every last drop of sweat and blood, and divvying up the wealth among themselves. Who in their right mind would become a Bolshevik unless that meant obtaining a bigger paycheck, guaranteed food rations, and a chance to move up in the world? The Communist Party needed realists. The idealists would starve. Those who were willing to say that the State was Revolution and obedience was freedom earned a chance to contribute their talents to building the new apparatus.

As for the suckers who remained workers rather than becoming Party officials, the Bolsheviks knew that the role of workers was to work. Workers who did not work were like broken machines. As any realist can tell you, when a machine breaks the only thing to do is take it out back and put a bullet in its brain.

Between March 12 and March 14, the Cheka cracked down in Astrakhan. They executed between 2000 and 4000 striking workers and Red Army deserters. Some they killed by firing squad, others by drowning them—tying stones around their necks and throwing them in the river. They had learned the latter technique from Lenin’s heroes, the Jacobins—enlightened bourgeois revolutionaries who massacred tens of thousands of peasants who weren’t educated enough to know that the commons were a thing of the past and land privatization was the way of the future.8

The Bolsheviks also killed a smaller number of members of the bourgeoisie, between 600 and 1000. The smartest of the bourgeoisie had already joined the Communist Party, recognizing it as the best way to profit in the new situation. But the stuffier bourgeois conservatives were staunchly opposed to the Bolsheviks, the anarchists, and the aristocrats, as well, though they weren’t against allying with the aristocrats. Any political system in which they could not do whatever they wanted to whomever they wanted, they called “tyranny.”

The bourgeois conservatives would also have crushed the striking workers, perhaps with hunger instead of bullets, if they had been in charge. Despite this, the Bolsheviks claimed that the striking workers had to be agents of the bourgeois order. Curiously, when anarchists had expropriated the bourgeoisie in Moscow in April, 1918, the Bolsheviks had called the anarchists “bandits” and returned the property to the bourgeois. Now, they killed bourgeois dissidents as well as striking workers—but they reserved the vast majority of the bullets for the workers.

Two days later, on March 16, the Cheka stormed the Putilov factory. They arrested 900 workers and executed 200 of them without a trial. These were pedagogical killings meant to “teach them a lesson,” educating the workers by executing their peers. The workers did not understand yet, but they would have to learn: workers were meant to work. If they had to starve, it was for the good of the proletariat.

The workers did not learn this lesson right away. At first, state repression only intensified worker opposition. According to intercepted Bolshevik cables, 60,000 workers were on strike in Petrograd alone in June 1919, three months after all the executions at the Putilov factory.9 The poor Bolsheviks had no choice but to kill even more workers and expand their gulag system to the point that it could reeducate not just thousands, but millions.

Many later Marxists unfairly blamed Josef Stalin for the USSR turning into a massive machinery of murder, but we can see the origins of that macabre evolution right here in the need of the Bolshevik authorities to kill workers in the name of workers. The entirety of the Party apparatus, from Lenin all the way down, dedicated itself to liquidating all opposition; and the entirety of this monstrous venture was ordained from the moment that the Communists decided that they were the conscious vanguard of the proletariat, that economic egalitarianism could be achieved through political elitism, and that liberatory ends justified authoritarian means.

1921: Requisitioning.

The Economic Policy of the Communist Party

Other revolutionary currents had conflicting ideas regarding the demands of workers and their instruments of self-organization. Some favored the factory councils that spontaneously arose around the February Revolution. Others favored the workers’ unions that had grown immensely in the course of 1917. Only the Bolsheviks had a realist position, changing their relationship with these structures according to which way the wind blew. As documented by Carlos Taibo,10 the Bolsheviks alternated between promoting the soviets and unions, attempting to capture them within larger bureaucratic structures controlled by the Party, eroding their powers, and suppressing them outright. Their approach varied wildly according to whether they believed that they could use these organizations to prop up their own power or feared, instead, that these organizations threatened Bolshevik supremacy. All power to the Party was their only consistent principle.

Throughout 1917, the Bolsheviks gained immense popularity by making all the right propaganda. They promised to redistribute the land directly to the peasants, to end the war without allowing imperialist Germany to annex territory, and to give the workers control of their workplaces. We have already seen how they broke the first two promises. As for their promise to the workers, they pitted different workers’ organizations against each another as they steadily strengthened their bureaucratic control.

In 1917, factory councils had sprung up in hundreds of factories throughout Russia, while membership in trade unions grew from tens of thousands to 1.5 million. At first, the Mensheviks dominated the unions and used their influence to get the unions to support the pre-October Kerensky government. According to a Trotskyist account, “As they were preparing for the seizure of power, Lenin and his followers tried to approach the trade unions from a new angle and to define their role in the Soviet system.” Promising them greater power, the Bolsheviks hoped to win union support for their project of seizing control of the State—or at least acquiescence to it.

According to two other pro-Leninist scholars, Lenin “essentially abandoned the slogan ‘All Power to the Soviets’” when he “convinced the party that the time was right to seize state power.”11 This is a fairly literal admission of fact. If the soviets were to have all the power, the Party could have none.

In November 1917, immediately after taking power, the Bolsheviks decreed that the factory committees must not participate in the direction of the companies, nor take on any responsibility in their functioning; instead, each committee was subordinated to a “Regional Council of Workers’ Control” which answered to the “All-Russian Council of Workers’ Control. The composition of these higher bodies was decided by the Party, with the trade unions receiving the majority of the seats.12

“The Revolution has been victorious. All power has passed to the Soviets… Strikes and demonstrations are harmful in Petrograd. We ask you to put an end to all strikes on economic and political issues, to resume work and to carry it out in a perfectly ordinary manner… Every man in his place. The best way to support the Soviet Government these days is to carry on with one’s job.”

-Bolshevik spokesmen at the second All-Russian Congress of Soviets, October 26 [Old Style calendar], 1917 (quoted in Maurice Brinton, The Bolsheviks and Workers’ Control 1917-1921)

“It is absolutely essential that all the authority in the factories should be concentrated in the hands of management… Under these circumstances any direct intervention by the trade unions in the management of enterprises must be regarded as positively harmful and impermissible.”

-Lenin speaking at the Eleventh Congress in 1922

Referring again to the Trotskyist account, “The Bolsheviks now called upon the trade unions to render a special service to the nascent Soviet state and to discipline the factory committees. The unions came out firmly against the attempt of the factory committees to form a national organization of their own. They prevented the convocation of a planned all-Russian congress of factory committees and demanded total subordination on the part of the committees.” At the end of 1917, the Bolsheviks forced the factory committees to incorporate themselves within the trade unions, in an attempt to curtail their autonomy.

1918: A shooting.

From the moment they were in power, the Bolsheviks treated workers’ councils as a threat. Why? Many Leninists, as well as the aforementioned Trotskyist, claimed that the councils were only conscious of their interests at the level of individual factories; they could not take into account the interests of the entire economy or the entire working class. This is contradicted, though, by the many examples of solidarity between soviets and workers’ councils across the country beginning already in 1917, and the fact of material support by peasants and urban workers for the anarchist detachments fighting against the White Army in the anarchist zones of Ukraine and Siberia, where idealist revolutionaries allowed workers and peasants to organize themselves. The simple fact that the factory councils were trying to coordinate at a countrywide level at the end of 1917 shows that they were in the process of developing what one might reasonably call a universal, proletarian, revolutionary consciousness; it was the Bolsheviks themselves who cut that process short.

From the Bolshevik perspective, what was most dangerous about factory council consciousness was that it might not lead to the particular kind of working-class consciousness that the Bolsheviks desperately needed to stay in power. Self-organized factories would support revolutionary armies of workers and peasants, but they probably would not support the Red Army in suppressing workers and peasants, nor would they support Lenin’s highly unpopular cession of Ukraine, Poland, and the Baltics to imperial Germany.

The councils were dangerous for another reason as well. Not only were they an organ of workers’ autonomy and self-organization that rendered any political party obsolete, they also tended to erode party discipline. Workers within the councils who were affiliated to the Mensheviks, the Bolsheviks, or any other party tended to act in accord with their common interests as factory workers rather than maintaining party interests.13

As Paul Avrich pointed out,14 the Bolsheviks made use of a nuanced distinction between two very different versions of workers’ control. Upravleniye meant direct control and self-organization by the workers themselves, but the Communist authorities refused to grant this demand. Their preferred slogan, rabochi control, did not denote anything beyond a nominal supervision of factory organization by workers. Under the system implemented by the Bolsheviks, workers participated in workplace decision-making together with the bosses, who could be the pre-Revolution capitalist owners or agents of the Party and the State, depending on Soviet policy at the moment.

All final decisions were made by the Supreme Soviet of the National Economy (the Vesenkha), an unelected, bureaucratic body established in December 1917 by decree of the Sovnarkom and the All-Russian Central Executive Committee. All of these bureaucratic bodies were controlled at all times by the Bolsheviks, meaning that no worker could have a final say in workplace decisions without becoming a full-time party operative and climbing to the very highest ranks of the bureaucracy.

Already in March 1918, an assembly of factory councils in Petrograd denounced the autocratic nature of Bolshevik rule and the Bolshevik attempt to dissolve those factory councils not under Party control.15 Such autocracy only increased when the Bolsheviks finally went ahead with the nationalization of the economy in the summer of 1918, increasing Party control and running the factories with the help of “experts” recruited from the old regime.

Though there was initially an ambiguous continuum between the economically oriented factory councils and the politically oriented town or village councils, the Communist Party quickly homogenized and bureaucratized the territorial soviets, starting with codes governing elections to the soviets in March 1918 and finishing by the time of the Soviet Constitution of 1922. Even more quickly, they got rid of the councils comprising all workers in a factory or other workplace, replacing them with symbolic worker representatives completely subordinate to a director appointed by the Party.

The Communists did all of this while paying lip service to their slogan and key campaign promise of 1917, “All Power to the Soviets.” They eventually got around the contradiction of simultaneously promoting and suppressing the soviets by declaring that councils of representatives of representatives, and even those of representatives of representatives of representatives, were also “soviets.” In fact, the committee furthest removed from any actual soviet of real-life peasants, workers, and soldiers was the “Supreme Soviet.” Since the Bolsheviks tightly controlled all these higher, more bureaucratic organs of government, which they had decided should also be called “soviets,” they could say “All Power to the Soviets” with a straight face—because now all they were saying was, “All Power to Us!”

This ingenious trick was very similar to the one used by the Founding Fathers of the United States, when an assortment of wealthy merchants and slave-owners established a government “of the People, by the People, and for the People.” Slave-owners qualified as people; slaves did not.

The Bolsheviks crushed the factory councils first, though they did not wait long to sink their teeth into the unions and drain them of their independence. It is noteworthy that they moved against the unions preemptively, preventing a possible threat to totalitarian rule even before the unions had offered any sign of resistance. At the First All-Russian Congress of Trade Unions in January 1918, the Bolsheviks successfully defended their position that the trade unions should be subordinated to the Soviet government, in the face of opposition by Mensheviks and anarchists, who argued that the unions should remain independent.

The Bolsheviks were able to dominate the unions using the All-Union Central Council of Trade Unions. By 1919, under the pretext of the extraordinary measures required by the Civil War, the Central Council had been fully incorporated into the bureaucracy that was now completely controlled by Party leadership.

Of course, as we have already shown, the Communist Party’s “extraordinary measures” preceded the Russian Civil War; they may have been the primary cause of the opposition and outrage that fueled the multiple and conflicting factions that fought in the Civil War.

In 1921, with the Civil War all but over and Bolshevik dominance indisputable, Lenin and his followers could do away with “war communism.” There followed more excuses about exceptional circumstances, delaying yet again the repartition of the pie in the sky that supposedly awaited the workers in paradise. The result was the New Economic Policy (NEP), which Lenin himself described as “a free market and capitalism, both subject to state control” together with state enterprises operating “on a profit basis.”16 Anarchists may have been among the first to level the accusation of “state capitalism,” but Lenin accepted the label as an objective fact.

In conclusion, the Bolsheviks seesawed from November 1917 to the NEP in 1921, changing their economic policy multiple times. Throughout these changes, they entrusted control over the workplace to capitalist bosses with symbolic worker oversight, to Party lackeys, to bureaucratic supreme committees, and to nepmen, the economic opportunists of the NEP era. It seems the only people the Bolsheviks were not willing to trust were the workers themselves.

Anti-colonial Marxist Walter Rodney, who was sympathetic to Stalin and wholly supportive of Lenin, nonetheless acknowledged that “The state, not the workers, effectively controlled the means of production.”17 He also showed how the Soviet Union inherited and furthered the Russian imperialism of the earlier tsarist regime—though that’s a topic for a future essay.

A realist knows that the best counterargument to all these sentimental complaints is the indisputable fact that, in the end, the Bolshevik strategy triumphed. They eliminated all their enemies. The idealists were dead—and therefore wrong. What better positive evidence can we find for the correctness of the Bolshevik position?

1919: in the basements of the Cheka.

The End of Resistance to Bolshevik Realism

Things immediately got better. The workers no longer had to toil for the enrichment of the capitalist class. Now they reaped the fruit of their own labors. (Except, of course, for all the workers in the free-market enterprises permitted under the NEP, and the millions of peasants who quite literally had to give away the fruits and the grains they grew.) To make things simpler, all the social wealth they reaped was kept in a trust managed by the intellectual workers. The intellectual workers worked a lot harder and required more compensation, better food, and bigger houses—but they also made sure that most of that wealth went to fielding an army of 11 million (shy by just a million of being the largest army in world history). And a damn fine opera. And one of the most extensive secret police apparatuses ever seen, too, to make sure the people stayed safe.

During Stalin’s Five Year Plans, the Soviet economy grew faster than the contemporary democratic economies and steered clear of the Depression that was ravishing much of the rest of the world. Idealistic anarchist critiques of “state capitalism” have long pointed out that the Communists were able to bring capitalism to the countries where the capitalist class had largely failed—they did capitalism better than the capitalists. But this naïve complaint misses out on the fact that a strong State, and thus a strong Revolution, requires a robust economy producing huge amounts of surplus value that can be reinvested as the Fathers of the Proletariat see fit.

Alongside all these exciting developments, the workers eventually got housing and healthcare, if they worked hard and kept their mouths shut. Provided, of course, that they weren’t among the millions of victims of the systematic famines designed to break the peasantry.

And that’s why these are such important days to remember.

On this, the one-hundred-year anniversary of the massacres of striking workers in Astrakhan and Petrograd, workers would do well to remember who has their best interests at heart, and keep in mind that obedience is freedom. To celebrate the triumph of the Bolshevik Revolution, which continues to shine as a beacon to oppressed people everywhere, workers should obey their elected union representatives, prisoners should heed their guards, soldiers should obey the command to fire, and the people should await the directives of the government. Anything else would be anarchy.

1922: A lesson on communism for the Russian peasants.

Bibliography

Paul Avrich, “Russian Anarchism and the Civil War,” The Russian Review. Vol.27 No.3: 296–306. July 1968.

Paul Avrich, The Russian Anarchists. Oakland: AK Press, 2006.

Maurice Brinton, The Bolsheviks and Workers’ Control 1917-1921. 1970.

Vladimir Brovkin, , “Workers’ Unrest and the Bolsheviks’ Response in 1919”, Slavic Review, 49 (3): 350–73. (Autumn 1990)

Isaac Deutscher, *Soviet Trade Unions: Their Place in Soviet Labour Policy. 1950. https://www.marxists.org/archive/deutscher/1950/soviet-trade-unions/ch02.htm

Nick Heath, “Bolshevik Repression against Anarchists in Vologda,” libcom.org October 15, 2017.

Robin D.G. Kelley and Jesse Benjamin, “Introduction,” in Walter Rodney, The Russian Revolution: A View from the Third World. London: Verso, 2018.

Piotr Kropotkin, The Great French Revolution. Montreal: Black Rose Books, 1989.

Nadezhda Krupskaya, “Illyich Moves to Moscow, His First Months of Work in Moscow” Reminiscences of Lenin. International Publishers, 1970.

George Leggett. The Cheka: Lenin’s Political Police. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1986.

V.I. Lenin, “Telegram to the Penza Gubernia Executive Committee of the Soviets” in J. Brooks and G. Chernyavskiy, Lenin and the Making of the Soviet State: A Brief History with Documents (2007). Bedford/St Martin’s: Boston and New York, p.77.

V.I. Lenin, “The Role and Functions of the Trade Unions under the New Economic Policy”, LCW, 33, p. 184., Decision Of The C.C., R.C.P.(B.), January 12, 1922. Published in Pravda No. 12, January 17, 1922. Lenin’s Collected Works, 2nd English Edition, Progress Publishers, Moscow, 1973, first printed 1965, Volume 33, pp. 186–196. https://www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/cw/pdf/lenin-cw-vol-33.pdf

Mário Machaquiero, A revolução soviética, hoje. Ensaio de releitura da revolução de 1917. Oporto: Afrontamento, 2008.

Igor Podshuvalov, Siberian Makhnovschina: Siberian Anarchists in the Russian Civil War (1918-1924). Edmonton: Black Cat Press, 2011.

James Ryan. Lenin’s Terror: The Ideological Origins of Early Soviet State Violence. London: Routledge, 2012.

Alexandre Skirda, trans. Paul Sharkey, Nestor Makhno: Anarchy’s Cossack. Oakland: AK Press, 2003.

Carlos Taibo, Soviets, Consejos de Fábrica, Comunas Rurales. Calumnia: Mallorca, 2017.

Various, A Collection of Reports on Bolshevism in Russia. London: HMSO, 1919.

Voline, The Unknown Revolution, 1917-1921. New York: Free Life Editions, 1974.

Dmitri Volkogonov, Shukman, Harold, ed., Trotsky: The Eternal Revolutionary, London: HarperCollins, p.180. 1996.

Nicolas Werth, Karel Bartosek, Jean-Louis Panne, Jean-Louis Margolin, Andrzej Paczkowski, Stephane Courtois, The Black Book of Communism: Crimes, Terror, Repression. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1999.

Beryl Williams, The Russian Revolution 1917–1921. Boston: Wiley-Blackwell, 1987.

Additional Reading

1921-1953: A Chronology of Russian Anarchism

Ilyich Moves to Moscow, His First Months of Work in Moscow, from Krupskaya’s “Reminiscences of Lenin”

Bolshevik repression against anarchists in Vologda

April 2018: One Hundred Year Anniversary of the Beginning of Bolshevik Terror

Lenin Orders the Massacre of Sex Workers, 1918

A Century since the Bolshevik Crackdown of August 1918

Manual for Revolutionary Leaders, Michael Velli

Of the seven members of the first Politburo—Lenin, Trotsky, Stalin, Kamenev, Sokolnikov, Zinoviev, and Bubnov—all but Zinoviev had received elite educations and become professional activists immediately after their education. Stalin was the only one of the seven who came from a less-than-middle class background. His father was a well-to-do shoemaker who owned his own workshop, though he lost his fortunes and became an abusive alcoholic. Young Stalin was able to receive an elite religious education thanks to his mother’s social connections. His first job was as a meteorologist; he later worked briefly at a storehouse in order to organize strike actions there.

Lenin and Sokolnikov were from families of professional white-collar workers; Bubnov was from a mercantile family; Kamenev was the son of a relatively well-paid worker in the railroad industry. Trotsky and Zinoviev were the children of landowning peasants, or kulaks—the very people they identified as the class enemy in the countryside in order to justify the murder of millions, both actual kulaks and poor peasants who opposed Bolshevik policies.

Most anarchists do not believe that a person’s class background determines their beliefs and attitudes, nor that it grants or denies them legitimacy as a human being. We recognize that how we grow up affects our perspective, but we tend to place more importance on how someone chooses to live their life. A few anarchists, like Kropotkin, came from elite backgrounds, whereas many more, such as Emma Goldman and Nestor Makhno, came from working-class or peasant backgrounds.

It is nonetheless significant that practically every single anarchist who was influential in the course of the Russian Revolution or who was chosen to lead a major detachment in the Civil War was a worker or a peasant. This exemplifies the slogan of the First International, “the liberation of the workers is the task of the workers themselves.” (The only exception was Volin, who came from a white-collar background.) It is also significant that, while the Bolsheviks recruited heavily among industrial workers, their entire Politburo was 0% working class.

Given both Marx and Lenin’s systematic use of their adversaries’ class identity—real or perceived—to delegitimize them or even justify murdering them, the fact that neither Marx nor Lenin nor the rest of the Communist leadership were working class is hypocritical to say the least. ↩

On the “blocking units” that did this, see Volkogonov, Dmitri (1996), Shukman, Harold, ed., Trotsky: The Eternal Revolutionary, London: HarperCollins, p.180. ↩

Brovkin, Vladimir (Autumn 1990), “Workers’ Unrest and the Bolsheviks’ Response in 1919”, Slavic Review, 49 (3): 350–73 ↩

Alexandre Skirda, trans. Paul Sharkey, Nestor Makhno: Anarchy’s Cossack. Oakland: AK Press, 2003 ↩

Beryl Williams, The Russian Revolution 1917–1921. Boston: Wiley-Blackwell, 1987. ↩

Even before Stalin, the Bolsheviks spread lies not so much to convince people of them as to force them to repeat the lies. This was an effective loyalty test: anyone who insisted on speaking the truth was clearly a dangerous counterrevolutionary, whereas those who called starving peasants “kulaks” or denounced principled revolutionary sailors as “White agents” had accepted Communist realism. ↩

“We, the workmen of the Putilov works and the wharf, declare before the laboring classes of Russia and the world, that the Bolshevik government has betrayed the high ideals of the October revolution, and thus betrayed and deceived the workmen and peasants of Russia; that the Bolshevik government, acting in our name, is not the authority of the proletariat and peasantry, but the authority of the Central Committee of the Communist Party, self-governing with the aid of the Extraordinary Commissions [Chekas], Communists, and police.

“We protest against the compulsion of workmen to remain at factories and works, and attempts to deprive them of all elementary rights: freedom of the press, speech, meetings, and inviolability of person.

“We demand:

Immediate transfer of authority to freely elected Workers’ and Peasants’ soviets. Immediate re-establishment of freedom of elections at factories and plants, barracks, ships, railways, everywhere.

Transfer of entire management to the released workers of the trade unions.

Transfer of food supply to workers’ and peasants’ cooperative societies.

General arming of workers and peasants.

Immediate release of members of the original revolutionary peasants’ party of Left Socialist Revolutionaries.

Immediate release of Maria Spiridonova [a Left SR leader].”

↩