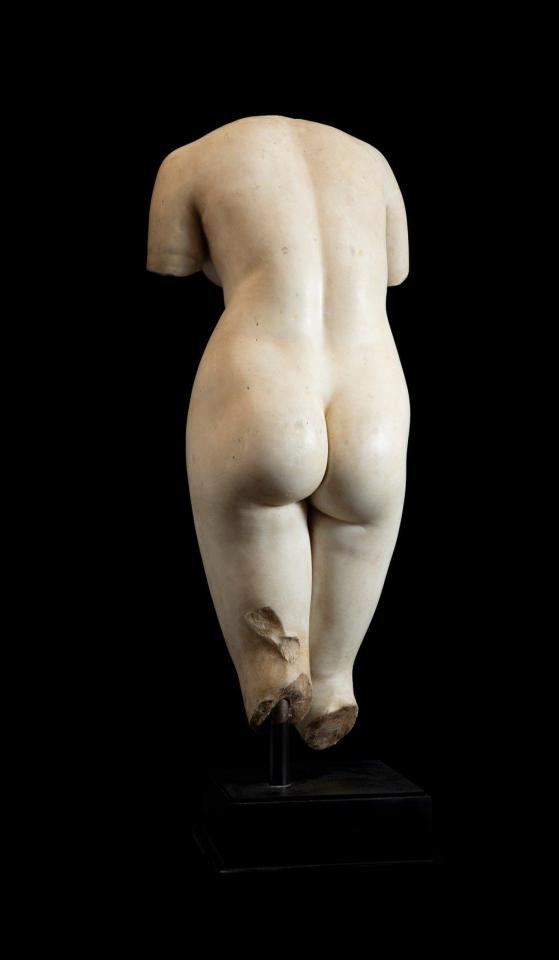

#Torso of Venus pudica

Text

Torso of Venus pudica. Roman, I-II centuries A.D.

Marble. (polished 18th-19th century)

841 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Art of the Day: Modest Venus (Venus Pudica)

This Venus, with her legs close together and a hand covering her genital area, is a "Venus Pudica," modest or chaste Venus. Her gesture implies awareness of an unexpected gaze: the viewer's. A nearly identical statuette (in the Basel Historisches Museum, Switzerland) was owned by the collector Basilius Amerbach (1533-91), who believed the statuette to be ancient. Both statuettes have silver-inlaid eyes, a feature copied from antique bronzes, as are Venus's corkscrew curls. The pose is derived from a much-studied ancient torso in a Roman collection. It is possible that these statuettes were created as "antiques," for which there was great demand. Learn more about this object in our art site: http://bit.ly/2Kicobf

11 notes

·

View notes

Photo

I’m all for repping the diversity of tiddie sizes on a single torso, but these afterthought looking growths are not the work of a man who’s ever seen a tiddie.

Sandro Botticelli, Venus pudica

0 notes

Text

Why Prehistoric Venus Figurines Still Mystify Experts

Venus of Willendorf, c. 28,000–25,000 B.C. Image by Helmut Fohringer / AFP / Getty Images.

Ample hips, voluminous breasts, uncovered pudenda—these are the most discussed features of the Stone Age statuettes of women commonly known as Venus figures or fertility figures. Dating as far back as around 40,000 B.C.E., the prehistoric statues have been touted as some of the earliest-known examples of figurative art worldwide. Yet they’re shrouded in mystery, and their interpretation has been influenced by over a century of cultural projection.

Archeologists have read them as goddess effigies, fertility talismans, likenesses of revered mothers, and nourishment charms. Many historians have focused on their exaggerated curves, but fewer have highlighted the range of body types they depict. Better-known examples, like the famed Venus of Willendorf, are voluptuous, while other, lesser-known figurines are usually more slender and lithe. We may never know exactly why these figurines were forged and who they depict, but that hasn’t stopped scholars from hypothesizing.

Female fertility figure, 5000 B.C.–9th Century A.D. Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of A

Drawing of Venus impudique, 1907. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

The first modern discovery of a Paleolithic statuette took place in 1864, thanks to a nobleman and amateur archeologist by the name of Paul Hurault, the 8th Marquis de Vibraye. While rooting around in the dig site of Laugerie-Basse in the Dordogne region of southwestern France, Hurault unearthed a 3-inch-tall ivory object. Though headless and armless, the figure retained a pronounced chest and clearly articulated vulva, boldly confirming it as female. Hurault, with satirical flair, named her Venus Impudique, or “immodest Venus,” a playful inversion of the classical Greek statue typology Venus pudica, in which a female figure modestly covers her genitals with a hand or cloth. By contrast, the Paleolithic figure seemed to take no pains to hide her sexuality.

Hurault didn’t know it then, but over 200 similar figurines from the Upper Paleolithic era would be unearthed across Europe and Asia, from France to Siberia, over the next century and a half. He not only launched this rash of discoveries, but also the tradition of calling the statuettes “Venuses.” It was a somewhat misleading name, given that the term originated in ancient Greece, tens of thousands of years after the Paleolithic figurines were made, to describe the goddess of love, sex, and fertility.

Carved in an era before written language, there is no clear proof about what these figurines represent. The most accurate clues scholars have about what the statuettes portrayed and why lie in the formal qualities of the figures themselves. Nearly all of them are petite—several inches long and diminutive enough to hold in a hand or string onto a cord (some even contain carved loops, seemingly for this purpose). The people who forged them led a nomadic life and some scholars conjecture that they intentionally made the figures small and light for easy transport. This hypothesis points to the personal value of the figurines and their possible devotional use. In this reading, the statuettes weren’t objects to be discarded, but ferried with their makers—held or strung close to bodies as they roamed from place to place.

Venus of Urbino, 1538.

Titian

Uffizi Gallery, Florence

Gender serves as another common thread across the Paleolithic figurines. Most are overtly female, and according to many scholars, even the ambiguous examples contain female attributes. While historians acknowledge that male figurines from this period could still surface, it seems that women were being depicted far more often. But why? What was their use? According to archeologist Nicholas J. Conard, one explanation rises above the rest: “Their clearly depicted sexual attributes,” he wrote in a 2009 issue of Nature, “suggest that they are a direct or indirect expression of fertility.”

Conard made this claim, which many other archeologists and historians have also espoused, in an article announcing his discovery of the oldest-known Paleolithic female figurine, dating between 40,000 and 35,000 B.C.E. (Other statuettes fall closer between 30,000 and 20,000 B.C.E.) In 2008, he and his team excavated six tiny pieces of mammoth ivory from the Hohle Fels cave in southwestern Germany. But it was only upon discovering the largest fragment—a lumpy, bulbous form—that “the importance of the discovery became apparent.” It was the majority of a torso: the linchpin of a female figure whose large breasts, rotund belly, and prodigious vulva take center stage. By comparison, her arms and legs appear slight, and in place of a head stands a carved ring (perhaps for original use as a pendant). Conrad put his interpretation bluntly: “Head and legs don’t matter. This is about sex, reproduction,” he told Smithsonian Magazine in 2012.

Venus of Hohle Fels, 35,000–40,000 B.C. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

Venus of Dolní Věstonice, 29,000–25,000 B.C. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

These proportions, in which areas of the body associated with reproduction (vulvas, breasts, hips, bellies) stand out, are typical of many Venus figurines. The Venus of Willendorf, which dates to around 25,000 years ago and was discovered in 1908, cuts a similar figure. The statuette’s pendulous breasts rest on a plump stomach, under which abundant hips and a pronounced vulva emerge. In comparison to the Hohle Fels Venus, Willendorf’s arms are even smaller and less defined, and while she has a head, its features seem intentionally obscured by a carved pattern resembling a woven hat or plaited hair.

But not all Paleolithic statuettes are so ample, nor their sexual organs as prominent. Some are slender or elongated; others adorned with crosshatching or other marks that might reference clothing. The figurines’ forms and features fluctuate, perhaps suggesting a breadth of models, aesthetic ideals, or uses. Conrad may be convinced that the statuettes represent fertility, but other scholars have made convincing arguments for their function as goddess figures, religious or shamanistic objects, or symbols of a matriarchal social organization.

The possibilities for interpretation seem endless, but as the archaeologist Olga Soffer has suggested, there should be limitations. Soffer warned against analyzing the figurines in terms of “18th-century Western European art.” While the misleading moniker “Venus” seems to have stuck, legions of archeologists and historians continue to reinterpret the cache of these statuettes, pushing them beyond narrow labels.

from Artsy News

0 notes