#Topaz War Relocation Center

Photo

My father, Susumu Yamashita, was a junior executive at the San Francisco branch of Mitsubishi trading company before the December 7, 1941 Japanese attack at Pearl Harbor. On April 30, 1942, he was involved in the mass forced removal of the Japanese American community from Berkeley to Tanforan detention center, a former race track in San Bruno, with my mother, Kiyoko Yamashita, and my 18 month-old sister Kimiko. My family was housed in a horse-stall “apartment” from May to September. When my family was transported to the Topaz, Utah incarceration camp in September 1942, my father was assigned to be the liaison to the Issei (first-generation) residents due to his Japanese-language proficiency, which was gained from his 11 years of education in Tokyo between 1911–1922. This is why he was labeled as a “Kibei,” American born but educated in Japan. After working 14 months in Community Welfare, providing the camp’s social services, my father was ready for a change. My Cal Berkeley/Harvard Business School-alumnus, ex-businessman father asked to be transferred to the agricultural division to work as a ranch hand. He achieved personal satisfaction from working outdoors as a Kibei cowboy, tanned and healthy, herding cattle astride his favorite horse, Red. At age 39, he was undoubtedly one of the oldest “cowboys” amongst the riders at the Topaz cattle ranch. In 1951 he rejoined Mitsubishi and was charged with establishing its New York headquarters as the new Mitsubishi International Corporation. After Topaz, my father never rode a horse again.

Michael Yamashita

#Susumu Yamashita#western riding#Utah#Topaz War Relocation Center#Central Utah Relocation Center (Topaz)#world war II#WWII#Michael Yamashita

170 notes

·

View notes

Text

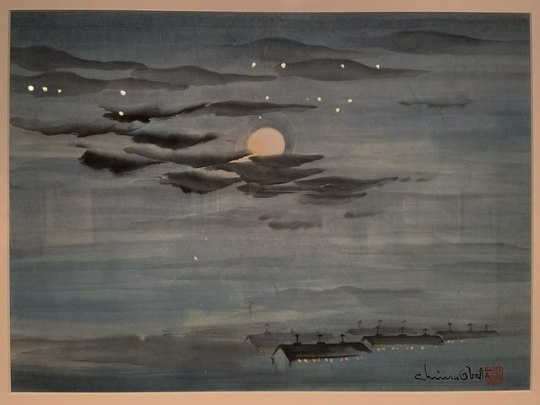

Chiura Obata, “Topaz War Relocation Center by Moonlight,” ca 1943

Berkley News. March 16, 2016. Chiura Obata: The beauty of bleakness

3 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

The Topaz War Relocation Center, also known as the Central Utah Relocation Center (Topaz) and briefly as the Abraham Relocation Center, was an American concentration camp that housed Americans of Japanese descent and immigrants who had come to the United States from Japan, called Nikkei. President Franklin Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 in February 1942, ordering people of Japanese ancestry to be incarcerated in what were euphemistically called "relocation centers" like Topaz during World War II. Most of the people incarcerated at Topaz came from the Tanforan Assembly Center and previously lived in the San Francisco Bay Area. The camp was opened in September 1942 and closed in October

Learn more

0 notes

Text

Mary Champagne is a multidisciplinary artist whose practice addresses the generational repercussions of forced relocation, referencing her grandfather’s experience as an interned Japanese-American during World War II and its subsequent impact on her family.

"Excavation (2019) is an image I took of the cracked desert earth at the site of the Topaz Relocation Center, June 2018. Much of the art produced by internees during Topaz referenced the novel climate as they described their own condition, lamenting that such infertile, arid soil would be unable to foster any transplanted life."--Mary Champagne

See work by Mary Champagne and 24 other artists online in Tradition - Memory - Transformation, the Asia North 2020 exhibition.

https://www.towson.edu/.../asia-north/exhibition-2020/

Image: Excavation by Mary Champagne. Handwoven cotton on TC2 Digital Jacquard loom from image, 20x44 inches.

0 notes

Photo

Topaz, Utah. James Wakasa funeral scene. 4/19/1943

Series: Central Photographic File of the War Relocation Authority, 1942 - 1945. Record Group 210: Records of the War Relocation Authority, 1941 - 1989

An internee of the Topaz War Relocation Center, James Wakasa was shot and killed by a military sentry on April 11, 1943 while walking near the camp fence.

Browse nearly 4,000 photos of Japanese American relocation and internment in the Central Photographic File of the War Relocation Authority in the @usnatarchives online catalog.

More Resources Commemorating the 75th Anniversary of Japanese American Internment at the National Archives

#Japanese American Internment#World War II#funeral#James Wakasa#internment#relocation#Topaz Relocation Center#Topaz#Utah#ww2#WWII75#japanese american relocation#archivesgov#April 19#1943#1940s#Asian American history

66 notes

·

View notes

Text

Utah museum acquires works by Japanese American artist Chiura Obata made in internment camp

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Today is Day of Remembrance. On this day, February 19, in 1942, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed into law Executive Order 9066, which paved the way for the mass incarceration of people of Japanese ancestry in World War II. This morning, I’d like to share some of my memories of learning more about the incarceration with you:

1. Tule Lake Segregation Center (2019): This was the third incarceration site I ever visited, on the California/Oregon border. Although much of the site has been lost to modern development, some of the original buildings, barbed wire fencing, and the jail (under the awning in the photo), built in 1945, remain.

2. Tulelake-Butte Valley Fairgrounds (2019): Near the former incarceration site at Tule Lake is a museum at the Tulelake-Butte Valley Fairgrounds. The museum is fairly small, but most striking to me was seeing one of the original guard towers in the yard. My step-grandparents were imprisoned at Tule Lake—I can’t help wondering if this was one of the guard towers they passed every day, on their way to the mess hall or to school.

3. Central Utah Relocation Center, also known as Topaz (2007): My mom and aunt took me on my first pilgrimage to Topaz back in 2007. This is me standing in the site of my grandpa’s old barracks. This was where he lived. For three years, with these strange horizons, behind barbed wire, this was where he lived. Photo by Kats Kitagawa.

4. Central Utah Relocation Center, also known as Topaz (c. 1942-1945): This is my grandpa and his family at the very same barracks during the incarceration. Because most cameras were confiscated after the attack on Pearl Harbor, we don’t have a lot of photographs from inside the camps, but there are a few, and they are precious—glimpses of these hard years, these injustices. I haven’t forgotten, family. I hope we never forget.

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

San Francisco, Calif., April 1942 - Children of the Weill public school, from the so-called international settlement, shown in a flag pledge ceremony. Some of them are evacuees of Japanese ancestry who will be housed in War relocation authority centers for the duration

ummary: Photograph shows multi-ethnic group of schoolgirls at the Raphael Weill Public School with their hands on their hearts saying the Pledge of Allegiance. Included in the photograph are Helene Mihara née Hideno Nakamoto (front row, Japanese American girl in plaid coat on the left) and Mary Ann Yahiro née Yoko Itashiki (front row, Japanese American girl in plaid coat on the right). In February 1942, Hideno's father, Jitsuzo Nakamoto, a San Francisco businessman, was arrested and incarcerated at Fort Lincoln, a Department of Justice camp for "enemy aliens" in Bismarck, North Dakota. He was later transferred to Lordsburg Internment Camp, Lordsburg, New Mexico, before being reunited with his family 15 months later at Tule Lake Relocation Center in Newell, California. Soon after the photograph was taken, Hideno, her mother, Fusaye, and her sister, Takako, were forcibly removed to Tanforan Assembly Center before being transferred to Tule Lake Relocation Center and later Central Utah Relocation Center, Topaz, Utah. Yoko's mother, Fuku Ogura Itasaki, a Japanese language teacher, was also arrested as an "enemy alien" and incarcerated at Camp Sharp Park, Sharp Park, California. She died there before being reunited with her family. Yoko's father, Torozimen Itashiki, and the rest of the family were forcibly removed to Tanforan Assembly Center before being transferred to Topaz. (Sources: interview with Helene Mihara, Nov. 29, 2021; Kitagaki, Paul, Jr. Behind barbed wire, 2019, page 29)

Reproduction Number: LC-USZ62-17124 (b&w film copy neg.)

Rights Advisory: No known restrictions on publication.

Call Number: LOT 1801 [item] [P&P]

Other Number: J 6738

Repository: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540 USA https://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/pp.print

Notes:

0 notes

Photo

San Francisco, Calif., Apr. 1942 - residents of Japanese ancestry registering for evacuation and housing, later, in War Relocation Authority centers for duration of the war (LOC) by The Library of Congress Lange, Dorothea,, photographer. San Francisco, Calif., Apr. 1942 - residents of Japanese ancestry registering for evacuation and housing, later, in War Relocation Authority centers for duration of the war [25 April 1942] 1 photograph : gelatin silver print. Notes: Photograph shows Shizuko Ina standing behind unidentified Japanese Americans at Kinmon Hall, San Francisco, on April 25, 1942, waiting for an appointment to be assigned "family number" 14911 before being removed from her home and incarcerated with her husband, Itaru Ina (1914-1977), in a detention facility at Tanforan Racetrack on April 30, 1942. She was later moved with her husband to a concentration camp in Topaz, Utah, and then to Tule Lake Segregation Center, near Newell in Northern California. The family was separated in July 1945 when Itaru was transferred to Fort Lincoln, a Department of Justice camp for "enemy aliens" in Bismarck, North Dakota, and reunited in April 1946 at Crystal City Internment Camp in Texas. (Source: Satsuki Ina, daughter of Shizuko Ina, February 2020) Title and other information transcribed from caption card and photo mount. Photographer and date from negative in the National Archives. Photograph from U.S. War Relocation Authority. No. A-572. Farm Security Administration and Office of War Information Collection (Library of Congress). Subjects: Ina, Shizuko--1917-2000. United States.--Wartime Civil Control Administration--1940-1950. Japanese Americans--Forced removal and internment, 1942-1945. World War, 1939-1945--Japanese Americans--California--San Francisco. Japanese Americans--Women--1940-1950. Political prisoners--California--San Francisco--1940-1950. Recording & registration--1940-1950. Waiting--1940-1950. Format: Photographic prints--1940-1950. Rights Info: No known restrictions on publication. Repository: Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, D.C. 20540 USA, hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/pp.print Part Of: Farm Security Administration - Office of War Information Photograph Collection (Library of Congress) (DLC) 2002708960 Higher resolution image is available (Persistent URL): hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/ppmsca.72649 Call Number: LOT 1801 [item] https://flic.kr/p/2mKNnDY

0 notes

Photo

Miné Okubo was an American artist and writer. She is best known for her book Citizen 13660, a collection of 189 drawings and accompanying text chronicling her experiences in Japanese American internment camps during World War II.Following the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, Okubo and her brother were interned to Tanforan Assembly Center and then the Topaz War Relocation Centerfrom 1942 to 1944. There she made over 2000 drawings and sketches of daily life in the camps, many of which were included in her book. Following six months of confinement at Tanforan, Okubo and her brother were transferred to the Topaz Relocation Center, Utah. Almost never without her sketchpad, Okubo recorded her images of drama, humiliation, and everyday struggle. While interned, Okubo taught art to children and later entered a magazine contest with her drawing of a camp guard. When Fortune magazine learned of her talent, the firm hired her as an illustrator, an arrangement that allowed her to leave the camp after a two-year confinement and relocate to New York City. Prior to her relocation to New York, Okubo had shipped a crate of her belongings to Fortune magazine’s offices. Okubo collaborated on the April 1944 special issue of Fortune magazine's article on Japan, a work that included a small number of her drawings — the first time any of her work had been published. She remained in New York, continuing her career as an artist, for the next half century. She worked as a freelance illustrator and later resumed painting full-time. Okubo testified in New York before the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians following its establishment in 1981. Citizen 13660 — by then widely reviewed and recognized as an important reference book on the internment — was presented to the commission by Okubo. Following her death in 2001, Okubo’s various artworks and papers were transferred to Riverside Community College District, a primary beneficiary of the estate, for preservation of the collection. #theunsungheroines (at Riverside Community College)

15 notes

·

View notes

Photo

This image depicts the housing conditions of Japanese American detainees experienced in a labor camp, 1942. During WWII, the Farm Security Administration and the War Relocation Authority operated the farm labor camps that employed Japanese American laborers to harvest crops like sugar beets, which were used to make sugar, rubber, ethanol and ammunition. Laborers were recruited first from temporary assembly centers in Portland, Oregon, Puyallup, Washington, Sacramento, Calififornia, and Stockton, California. Japanese American laborers later came from behind the barbwire fences of Heart Mountain, Manzanar, Minidoka, Topaz and Tule Lake.

Photo credit: Russell Lee / Library of Congress — in Rupert, Idaho.

#russell lee#farm labor camp#wwii#ww2#world war ii#world war 2#war#indefinite detention#crime#law#rupert#idaho

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

The art of endurance

The art of endurance

Dust Storm, Topaz, March 13 (1943, Watercolor on paper)

I recently finished listening to an audiobook called Enemy Child: The Story of Norman Mineta, written by Andrea Warren. Norman Mineta was born and grew up in San Jose, California; in 1942 he was an 11-year-old Cub Scout when he and his family were sent to Heart Mountain War Relocation Centerin Wyoming. After the war his family were very…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Topaz 1942 - 1946

Topaz 1942 – 1946

Topaz 1942 – 1946

Central Utah WRA Relocation Center

Fifteen miles west at Abraham is the location of the bleak desert site of a concentration camp, one of ten in Western America, in which 110,000 persons of Japanese ancestry were interned against their will during World War II. They were the victims of wartime hysteria, racial animosity, and economic opportunism on the West Coast.

Confi…

View On WordPress

#Concentration Camps#Delta#Historic Markers#Millard County#National Historic Landmarks#NRHP#utah#World War II

0 notes

Photo

If you ever find yourself in Sacramento, stop by @crockerart. It’s a wonderful museum & I’m glad I made the time. - Of particular note was the current exhibition of artist Chiura Obata, a Japanese immigrant who arrived in America in 1903 and whose career in the arts included being an educator at Berkeley. The survey covered his entire career, but of particular interest to me was his ink drawings during his time in the Topaz internment camp in Utah. - Obata joined 120,000 other Japanese Americans in internment camps after the bombing of a Pearl Harbor throughout World War II. He captured scenes from this dark period of our nation’s history directly in his artwork. He even founded two art schools in internment camps during this time. - One piece in particular caught my eye: the internment camp captured in watercolor in moonlight. It reminded me of another modern piece for artist Roger Shimomura: “Night Watch # 7”, an American-born artist who depicts his family’s internment at Minidoka, Idaho (swipe👆➡️). - Both take a view from the distance. Obata’s seems like a tiny village caught in a fog — a deceptive view. Shimomura frames the similar housing with soldiers looking down and barbed wire in the background. The fog is lifted and we see an unflattering view of the past. - I’d never seen artworks around the subject of the Japanese-American internment before. I wish more people could view them and they were better known — and I’m glad the Crocker features them, especially now as our nation debates over the use immigration detention centers and family separation. It’s depressing to think that after seven decades we refuse to learn from the errors of our past. - I left pondering what my grandpa would think: about the art and about our nation right now. He was a child who also was in an internment camp and learning from him about it makes me sensitive to the subject today. When the U.S. government apologized in 1988, it admitted the forced relocation and imprisonment came directly from “race prejudice, war hysteria, and a failure of political leadership”. Not much seems to have changed. https://ift.tt/2Nu6M3d

0 notes

Photo

“Topaz, Utah. Bennie Nobori, former animator in a Hollywood film studio, is now a cartoonist on the Topaz Times. Bennie has a regular cartoon strip which appears in the paper at the center…” 3/11/1943

Stewart, Francis, War Relocation Authority photographer, Series: Central Photographic File of the War Relocation Authority, 1942 - 1945. Record Group 210: Records of the War Relocation Authority, 1941 - 1989

Professional photographers were commissioned by the War Relocation Authority to document the daily life and treatment of Japanese-Americans who were interned during World War II.

Browse nearly 4,000 photos of Japanese American relocation and internment in the Central Photographic File of the War Relocation Authority in the @usnatarchives online catalog.

More Resources Commemorating the 75th Anniversary of Japanese American Internment at the National Archives

#Japanese American Internment#World War II#Cartoonist#cartoon#art#artist#Asian American History#ww2#WWII75#Topaz Relocation Center#Utah#Francis Stewart#March 11#1943#1940s

94 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Our collections contain many forms of identification. The Kay Sekimachi and Bob Stocksdale papers presented an unfortunate remnant of President Franklin Roosevelt's Executive Order 9066 which forcibly interned over 100,000 Japanese and Japanese-American citizens living on the West Coast during World War II. This ID card gave Kay Sekimachi permission to leave the Topaz War Relocation Center in Utah.

70 notes

·

View notes