#The Medieval City

Text

It's fascinating to me that for our modern (at least on European-influenced societies) thinking, the classical Roman way of life is so familiar. When you read about it, the rethoric of the speeches feels modern, a society based on contracts and laws and litigation, with public works, a state bureucracy and standing army and trade economy and even spectator sports, a concept of philosophy separated from religious dogma and tradition, with even a limited understanding of a government by 'the people' and 'citizenship', even the names all sound familiar even if in completely different contexts, and no wonder since they inspired our current politics.

This all in contrast to medieval feudalism, which is completely alien to me. A society created upon family connections and oaths of fealty and serfdom with no such thing as an overarching state, not even kingdoms were any more real than a title one person holds, and all held together completely, utterly, to an extent I cannot emphasize enough, by the institution of the Church and the Christian faith. In a way we just aren't used today in our secular world. I simply cannot overstate how everything, every single thing, was permeated by faith in the Medieval worldview and the Church which took its power from it, we have an understanding of it but I think people just don't realize it.

#cosas mias#this is a very silly example so bear with me#the other day I was watching some Manor Lords playthroughs#and a guy was complaining his medieval village wasn't growing#it was because no matter all the economic resources it had it didn't have a church#of course that for those people a place without a church is a non-place to start with never mind anything else#(and even the game oversimplifies that)#what I mean by these stupid tags is that we see religion as something private... for them it meant literally EVERYTHING#in a way we don't understand sure we can imagine a city without imagining churches... for someone on the middle ages#a Place was a Place where a Church was

822 notes

·

View notes

Photo

doeeme

#estonia#city#cityscape#urban architecture#medieval city#travel#travelblr#travel photography#travelcore#roamtheplanet#beautifuldestinations#cozy corner#instagram#yuploads

3K notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Medieval City

We turn to imagine some city of the Middle Ages. Here also would be as in an ancient city, a long circuit of walls, with gates and towers, a military and highly organised society, a complex religious system, intense civic pride and patriotism. And yet the differences are vast. The grand difference of all is that the city is no longer the State, except in some parts of Italy, and even there not in the early Middle Ages. In the early Middle Ages, the city is not the State or the nation: it is only a stronghold, or fortified magazine in the barony, duchy, kingdom, or empire.

It is only a big and very complicated castle, with its defensive system exactly like any other castle, governed by a mayor, bailiff, or prior, and the burgher council, and not necessarily by a feudal lord. Except in Italy and a few free towns along the Mediterranean at particular periods, no city counted itself as wholly outside the jurisdiction of some overlord, king, or emperor.

Apart from its political and legal privileges, a mediaeval city was something like Windsor Castle or the Tower of London, on a large scale and with many subdivisions, governed by an elected corporation and not by a baron or viceroy. The ancient city, however much it had to fear war and opposition from its rival cities or states, could feel safe within its own territories from any attack on the part of its rural neighbours, subjects, or fellow-citizens. There it was mistress, or rather the city included the territory around it. No Athenian ever dreamed of being invaded by the inhabitants of Attica, or even of Boeotia. No Roman troubled himself about Latians or Etruscans other than the citizens of Latian or Tuscan cities. City life in the Middle Ages was a very different thing. Until a mediaeval city became very strong and had secured round itself an ample territory, it was always in difficulties with the lords of neighbouring fiefs and castles city tours istanbul.

Even in Italy, before the great cities had crushed the feudal-lords and had forced them to become citizens, the mediaeval cities had constantly to fight for their existence against chiefs whose castles lay within sight. The ancient city was a State — the collective centre of an organised territory, supreme within it, and owing no fealty to any other sovereign, temporal or spiritual, outside its own territory. The mediaeval city was only a privileged town within a fief or kingdom, having charters, rights, and fortifications of its own; but, both in religious and in political rank, bound in absolute duty to far distant and much more exalted superiors.

Defensive system vastly more elaborate

Partly as a consequence of its being in constant danger from its neighbours, it had a defensive system vastly more elaborate than that of ancient cities. Its outer walls were of enormous height, thickness, and complexity. They were flanked with gigantic towers, gates, posterns, and watch-towers; it had a broad moat round ‘it and a complicated series of drawbridges, stockades, barbicans, and outworks. We may see something of it in the old city of Carcassonne in the south of France, destroyed by St. Louis in 1262, in the walls of Rome round the Vatican, and in the old walls of Constantinople on the western side near the Gate of St. Romanus. From without the Mediaeval City looked like a vast castle. And the military discipline and precautions were entirely those of a castle.

In peace or war, it was a fortress first, and a dwelling- place afterwards. This vast apparatus of defence cramped the space and shut out light, air, and prospect. Few ancient cities would have looked from without like a fortress; for the walls were much lower and simpler, in the absence of any elaborate system of artillery. But the Mediaeval City with its far loftier walls, towers, gates, and successive defences looked more like a prison than a town, and indeed to a great extent it was a prison.

There could seldom have been much prospect from within it, except of its own walls and towers; there were few open spaces, usually there was one small market-place, no public gardens or walks; the city was encumbered with castles, monasteries, and castellated enclosures; and the bridges and quays were crowded with a confused pile of lofty wooden houses; and, as the walls necessarily ran along any sea or river frontage that the city had, it was impossible to get any general view of the town, or to look up or down the river for the closely-packed buildings on the bridges.

0 notes

Photo

The Medieval City

We turn to imagine some city of the Middle Ages. Here also would be as in an ancient city, a long circuit of walls, with gates and towers, a military and highly organised society, a complex religious system, intense civic pride and patriotism. And yet the differences are vast. The grand difference of all is that the city is no longer the State, except in some parts of Italy, and even there not in the early Middle Ages. In the early Middle Ages, the city is not the State or the nation: it is only a stronghold, or fortified magazine in the barony, duchy, kingdom, or empire.

It is only a big and very complicated castle, with its defensive system exactly like any other castle, governed by a mayor, bailiff, or prior, and the burgher council, and not necessarily by a feudal lord. Except in Italy and a few free towns along the Mediterranean at particular periods, no city counted itself as wholly outside the jurisdiction of some overlord, king, or emperor.

Apart from its political and legal privileges, a mediaeval city was something like Windsor Castle or the Tower of London, on a large scale and with many subdivisions, governed by an elected corporation and not by a baron or viceroy. The ancient city, however much it had to fear war and opposition from its rival cities or states, could feel safe within its own territories from any attack on the part of its rural neighbours, subjects, or fellow-citizens. There it was mistress, or rather the city included the territory around it. No Athenian ever dreamed of being invaded by the inhabitants of Attica, or even of Boeotia. No Roman troubled himself about Latians or Etruscans other than the citizens of Latian or Tuscan cities. City life in the Middle Ages was a very different thing. Until a mediaeval city became very strong and had secured round itself an ample territory, it was always in difficulties with the lords of neighbouring fiefs and castles city tours istanbul.

Even in Italy, before the great cities had crushed the feudal-lords and had forced them to become citizens, the mediaeval cities had constantly to fight for their existence against chiefs whose castles lay within sight. The ancient city was a State — the collective centre of an organised territory, supreme within it, and owing no fealty to any other sovereign, temporal or spiritual, outside its own territory. The mediaeval city was only a privileged town within a fief or kingdom, having charters, rights, and fortifications of its own; but, both in religious and in political rank, bound in absolute duty to far distant and much more exalted superiors.

Defensive system vastly more elaborate

Partly as a consequence of its being in constant danger from its neighbours, it had a defensive system vastly more elaborate than that of ancient cities. Its outer walls were of enormous height, thickness, and complexity. They were flanked with gigantic towers, gates, posterns, and watch-towers; it had a broad moat round ‘it and a complicated series of drawbridges, stockades, barbicans, and outworks. We may see something of it in the old city of Carcassonne in the south of France, destroyed by St. Louis in 1262, in the walls of Rome round the Vatican, and in the old walls of Constantinople on the western side near the Gate of St. Romanus. From without the Mediaeval City looked like a vast castle. And the military discipline and precautions were entirely those of a castle.

In peace or war, it was a fortress first, and a dwelling- place afterwards. This vast apparatus of defence cramped the space and shut out light, air, and prospect. Few ancient cities would have looked from without like a fortress; for the walls were much lower and simpler, in the absence of any elaborate system of artillery. But the Mediaeval City with its far loftier walls, towers, gates, and successive defences looked more like a prison than a town, and indeed to a great extent it was a prison.

There could seldom have been much prospect from within it, except of its own walls and towers; there were few open spaces, usually there was one small market-place, no public gardens or walks; the city was encumbered with castles, monasteries, and castellated enclosures; and the bridges and quays were crowded with a confused pile of lofty wooden houses; and, as the walls necessarily ran along any sea or river frontage that the city had, it was impossible to get any general view of the town, or to look up or down the river for the closely-packed buildings on the bridges.

0 notes

Photo

The Medieval City

We turn to imagine some city of the Middle Ages. Here also would be as in an ancient city, a long circuit of walls, with gates and towers, a military and highly organised society, a complex religious system, intense civic pride and patriotism. And yet the differences are vast. The grand difference of all is that the city is no longer the State, except in some parts of Italy, and even there not in the early Middle Ages. In the early Middle Ages, the city is not the State or the nation: it is only a stronghold, or fortified magazine in the barony, duchy, kingdom, or empire.

It is only a big and very complicated castle, with its defensive system exactly like any other castle, governed by a mayor, bailiff, or prior, and the burgher council, and not necessarily by a feudal lord. Except in Italy and a few free towns along the Mediterranean at particular periods, no city counted itself as wholly outside the jurisdiction of some overlord, king, or emperor.

Apart from its political and legal privileges, a mediaeval city was something like Windsor Castle or the Tower of London, on a large scale and with many subdivisions, governed by an elected corporation and not by a baron or viceroy. The ancient city, however much it had to fear war and opposition from its rival cities or states, could feel safe within its own territories from any attack on the part of its rural neighbours, subjects, or fellow-citizens. There it was mistress, or rather the city included the territory around it. No Athenian ever dreamed of being invaded by the inhabitants of Attica, or even of Boeotia. No Roman troubled himself about Latians or Etruscans other than the citizens of Latian or Tuscan cities. City life in the Middle Ages was a very different thing. Until a mediaeval city became very strong and had secured round itself an ample territory, it was always in difficulties with the lords of neighbouring fiefs and castles city tours istanbul.

Even in Italy, before the great cities had crushed the feudal-lords and had forced them to become citizens, the mediaeval cities had constantly to fight for their existence against chiefs whose castles lay within sight. The ancient city was a State — the collective centre of an organised territory, supreme within it, and owing no fealty to any other sovereign, temporal or spiritual, outside its own territory. The mediaeval city was only a privileged town within a fief or kingdom, having charters, rights, and fortifications of its own; but, both in religious and in political rank, bound in absolute duty to far distant and much more exalted superiors.

Defensive system vastly more elaborate

Partly as a consequence of its being in constant danger from its neighbours, it had a defensive system vastly more elaborate than that of ancient cities. Its outer walls were of enormous height, thickness, and complexity. They were flanked with gigantic towers, gates, posterns, and watch-towers; it had a broad moat round ‘it and a complicated series of drawbridges, stockades, barbicans, and outworks. We may see something of it in the old city of Carcassonne in the south of France, destroyed by St. Louis in 1262, in the walls of Rome round the Vatican, and in the old walls of Constantinople on the western side near the Gate of St. Romanus. From without the Mediaeval City looked like a vast castle. And the military discipline and precautions were entirely those of a castle.

In peace or war, it was a fortress first, and a dwelling- place afterwards. This vast apparatus of defence cramped the space and shut out light, air, and prospect. Few ancient cities would have looked from without like a fortress; for the walls were much lower and simpler, in the absence of any elaborate system of artillery. But the Mediaeval City with its far loftier walls, towers, gates, and successive defences looked more like a prison than a town, and indeed to a great extent it was a prison.

There could seldom have been much prospect from within it, except of its own walls and towers; there were few open spaces, usually there was one small market-place, no public gardens or walks; the city was encumbered with castles, monasteries, and castellated enclosures; and the bridges and quays were crowded with a confused pile of lofty wooden houses; and, as the walls necessarily ran along any sea or river frontage that the city had, it was impossible to get any general view of the town, or to look up or down the river for the closely-packed buildings on the bridges.

0 notes

Photo

The Medieval City

We turn to imagine some city of the Middle Ages. Here also would be as in an ancient city, a long circuit of walls, with gates and towers, a military and highly organised society, a complex religious system, intense civic pride and patriotism. And yet the differences are vast. The grand difference of all is that the city is no longer the State, except in some parts of Italy, and even there not in the early Middle Ages. In the early Middle Ages, the city is not the State or the nation: it is only a stronghold, or fortified magazine in the barony, duchy, kingdom, or empire.

It is only a big and very complicated castle, with its defensive system exactly like any other castle, governed by a mayor, bailiff, or prior, and the burgher council, and not necessarily by a feudal lord. Except in Italy and a few free towns along the Mediterranean at particular periods, no city counted itself as wholly outside the jurisdiction of some overlord, king, or emperor.

Apart from its political and legal privileges, a mediaeval city was something like Windsor Castle or the Tower of London, on a large scale and with many subdivisions, governed by an elected corporation and not by a baron or viceroy. The ancient city, however much it had to fear war and opposition from its rival cities or states, could feel safe within its own territories from any attack on the part of its rural neighbours, subjects, or fellow-citizens. There it was mistress, or rather the city included the territory around it. No Athenian ever dreamed of being invaded by the inhabitants of Attica, or even of Boeotia. No Roman troubled himself about Latians or Etruscans other than the citizens of Latian or Tuscan cities. City life in the Middle Ages was a very different thing. Until a mediaeval city became very strong and had secured round itself an ample territory, it was always in difficulties with the lords of neighbouring fiefs and castles city tours istanbul.

Even in Italy, before the great cities had crushed the feudal-lords and had forced them to become citizens, the mediaeval cities had constantly to fight for their existence against chiefs whose castles lay within sight. The ancient city was a State — the collective centre of an organised territory, supreme within it, and owing no fealty to any other sovereign, temporal or spiritual, outside its own territory. The mediaeval city was only a privileged town within a fief or kingdom, having charters, rights, and fortifications of its own; but, both in religious and in political rank, bound in absolute duty to far distant and much more exalted superiors.

Defensive system vastly more elaborate

Partly as a consequence of its being in constant danger from its neighbours, it had a defensive system vastly more elaborate than that of ancient cities. Its outer walls were of enormous height, thickness, and complexity. They were flanked with gigantic towers, gates, posterns, and watch-towers; it had a broad moat round ‘it and a complicated series of drawbridges, stockades, barbicans, and outworks. We may see something of it in the old city of Carcassonne in the south of France, destroyed by St. Louis in 1262, in the walls of Rome round the Vatican, and in the old walls of Constantinople on the western side near the Gate of St. Romanus. From without the Mediaeval City looked like a vast castle. And the military discipline and precautions were entirely those of a castle.

In peace or war, it was a fortress first, and a dwelling- place afterwards. This vast apparatus of defence cramped the space and shut out light, air, and prospect. Few ancient cities would have looked from without like a fortress; for the walls were much lower and simpler, in the absence of any elaborate system of artillery. But the Mediaeval City with its far loftier walls, towers, gates, and successive defences looked more like a prison than a town, and indeed to a great extent it was a prison.

There could seldom have been much prospect from within it, except of its own walls and towers; there were few open spaces, usually there was one small market-place, no public gardens or walks; the city was encumbered with castles, monasteries, and castellated enclosures; and the bridges and quays were crowded with a confused pile of lofty wooden houses; and, as the walls necessarily ran along any sea or river frontage that the city had, it was impossible to get any general view of the town, or to look up or down the river for the closely-packed buildings on the bridges.

0 notes

Photo

The Medieval City

We turn to imagine some city of the Middle Ages. Here also would be as in an ancient city, a long circuit of walls, with gates and towers, a military and highly organised society, a complex religious system, intense civic pride and patriotism. And yet the differences are vast. The grand difference of all is that the city is no longer the State, except in some parts of Italy, and even there not in the early Middle Ages. In the early Middle Ages, the city is not the State or the nation: it is only a stronghold, or fortified magazine in the barony, duchy, kingdom, or empire.

It is only a big and very complicated castle, with its defensive system exactly like any other castle, governed by a mayor, bailiff, or prior, and the burgher council, and not necessarily by a feudal lord. Except in Italy and a few free towns along the Mediterranean at particular periods, no city counted itself as wholly outside the jurisdiction of some overlord, king, or emperor.

Apart from its political and legal privileges, a mediaeval city was something like Windsor Castle or the Tower of London, on a large scale and with many subdivisions, governed by an elected corporation and not by a baron or viceroy. The ancient city, however much it had to fear war and opposition from its rival cities or states, could feel safe within its own territories from any attack on the part of its rural neighbours, subjects, or fellow-citizens. There it was mistress, or rather the city included the territory around it. No Athenian ever dreamed of being invaded by the inhabitants of Attica, or even of Boeotia. No Roman troubled himself about Latians or Etruscans other than the citizens of Latian or Tuscan cities. City life in the Middle Ages was a very different thing. Until a mediaeval city became very strong and had secured round itself an ample territory, it was always in difficulties with the lords of neighbouring fiefs and castles city tours istanbul.

Even in Italy, before the great cities had crushed the feudal-lords and had forced them to become citizens, the mediaeval cities had constantly to fight for their existence against chiefs whose castles lay within sight. The ancient city was a State — the collective centre of an organised territory, supreme within it, and owing no fealty to any other sovereign, temporal or spiritual, outside its own territory. The mediaeval city was only a privileged town within a fief or kingdom, having charters, rights, and fortifications of its own; but, both in religious and in political rank, bound in absolute duty to far distant and much more exalted superiors.

Defensive system vastly more elaborate

Partly as a consequence of its being in constant danger from its neighbours, it had a defensive system vastly more elaborate than that of ancient cities. Its outer walls were of enormous height, thickness, and complexity. They were flanked with gigantic towers, gates, posterns, and watch-towers; it had a broad moat round ‘it and a complicated series of drawbridges, stockades, barbicans, and outworks. We may see something of it in the old city of Carcassonne in the south of France, destroyed by St. Louis in 1262, in the walls of Rome round the Vatican, and in the old walls of Constantinople on the western side near the Gate of St. Romanus. From without the Mediaeval City looked like a vast castle. And the military discipline and precautions were entirely those of a castle.

In peace or war, it was a fortress first, and a dwelling- place afterwards. This vast apparatus of defence cramped the space and shut out light, air, and prospect. Few ancient cities would have looked from without like a fortress; for the walls were much lower and simpler, in the absence of any elaborate system of artillery. But the Mediaeval City with its far loftier walls, towers, gates, and successive defences looked more like a prison than a town, and indeed to a great extent it was a prison.

There could seldom have been much prospect from within it, except of its own walls and towers; there were few open spaces, usually there was one small market-place, no public gardens or walks; the city was encumbered with castles, monasteries, and castellated enclosures; and the bridges and quays were crowded with a confused pile of lofty wooden houses; and, as the walls necessarily ran along any sea or river frontage that the city had, it was impossible to get any general view of the town, or to look up or down the river for the closely-packed buildings on the bridges.

0 notes

Photo

The Medieval City

We turn to imagine some city of the Middle Ages. Here also would be as in an ancient city, a long circuit of walls, with gates and towers, a military and highly organised society, a complex religious system, intense civic pride and patriotism. And yet the differences are vast. The grand difference of all is that the city is no longer the State, except in some parts of Italy, and even there not in the early Middle Ages. In the early Middle Ages, the city is not the State or the nation: it is only a stronghold, or fortified magazine in the barony, duchy, kingdom, or empire.

It is only a big and very complicated castle, with its defensive system exactly like any other castle, governed by a mayor, bailiff, or prior, and the burgher council, and not necessarily by a feudal lord. Except in Italy and a few free towns along the Mediterranean at particular periods, no city counted itself as wholly outside the jurisdiction of some overlord, king, or emperor.

Apart from its political and legal privileges, a mediaeval city was something like Windsor Castle or the Tower of London, on a large scale and with many subdivisions, governed by an elected corporation and not by a baron or viceroy. The ancient city, however much it had to fear war and opposition from its rival cities or states, could feel safe within its own territories from any attack on the part of its rural neighbours, subjects, or fellow-citizens. There it was mistress, or rather the city included the territory around it. No Athenian ever dreamed of being invaded by the inhabitants of Attica, or even of Boeotia. No Roman troubled himself about Latians or Etruscans other than the citizens of Latian or Tuscan cities. City life in the Middle Ages was a very different thing. Until a mediaeval city became very strong and had secured round itself an ample territory, it was always in difficulties with the lords of neighbouring fiefs and castles city tours istanbul.

Even in Italy, before the great cities had crushed the feudal-lords and had forced them to become citizens, the mediaeval cities had constantly to fight for their existence against chiefs whose castles lay within sight. The ancient city was a State — the collective centre of an organised territory, supreme within it, and owing no fealty to any other sovereign, temporal or spiritual, outside its own territory. The mediaeval city was only a privileged town within a fief or kingdom, having charters, rights, and fortifications of its own; but, both in religious and in political rank, bound in absolute duty to far distant and much more exalted superiors.

Defensive system vastly more elaborate

Partly as a consequence of its being in constant danger from its neighbours, it had a defensive system vastly more elaborate than that of ancient cities. Its outer walls were of enormous height, thickness, and complexity. They were flanked with gigantic towers, gates, posterns, and watch-towers; it had a broad moat round ‘it and a complicated series of drawbridges, stockades, barbicans, and outworks. We may see something of it in the old city of Carcassonne in the south of France, destroyed by St. Louis in 1262, in the walls of Rome round the Vatican, and in the old walls of Constantinople on the western side near the Gate of St. Romanus. From without the Mediaeval City looked like a vast castle. And the military discipline and precautions were entirely those of a castle.

In peace or war, it was a fortress first, and a dwelling- place afterwards. This vast apparatus of defence cramped the space and shut out light, air, and prospect. Few ancient cities would have looked from without like a fortress; for the walls were much lower and simpler, in the absence of any elaborate system of artillery. But the Mediaeval City with its far loftier walls, towers, gates, and successive defences looked more like a prison than a town, and indeed to a great extent it was a prison.

There could seldom have been much prospect from within it, except of its own walls and towers; there were few open spaces, usually there was one small market-place, no public gardens or walks; the city was encumbered with castles, monasteries, and castellated enclosures; and the bridges and quays were crowded with a confused pile of lofty wooden houses; and, as the walls necessarily ran along any sea or river frontage that the city had, it was impossible to get any general view of the town, or to look up or down the river for the closely-packed buildings on the bridges.

0 notes

Photo

The Medieval City

We turn to imagine some city of the Middle Ages. Here also would be as in an ancient city, a long circuit of walls, with gates and towers, a military and highly organised society, a complex religious system, intense civic pride and patriotism. And yet the differences are vast. The grand difference of all is that the city is no longer the State, except in some parts of Italy, and even there not in the early Middle Ages. In the early Middle Ages, the city is not the State or the nation: it is only a stronghold, or fortified magazine in the barony, duchy, kingdom, or empire.

It is only a big and very complicated castle, with its defensive system exactly like any other castle, governed by a mayor, bailiff, or prior, and the burgher council, and not necessarily by a feudal lord. Except in Italy and a few free towns along the Mediterranean at particular periods, no city counted itself as wholly outside the jurisdiction of some overlord, king, or emperor.

Apart from its political and legal privileges, a mediaeval city was something like Windsor Castle or the Tower of London, on a large scale and with many subdivisions, governed by an elected corporation and not by a baron or viceroy. The ancient city, however much it had to fear war and opposition from its rival cities or states, could feel safe within its own territories from any attack on the part of its rural neighbours, subjects, or fellow-citizens. There it was mistress, or rather the city included the territory around it. No Athenian ever dreamed of being invaded by the inhabitants of Attica, or even of Boeotia. No Roman troubled himself about Latians or Etruscans other than the citizens of Latian or Tuscan cities. City life in the Middle Ages was a very different thing. Until a mediaeval city became very strong and had secured round itself an ample territory, it was always in difficulties with the lords of neighbouring fiefs and castles city tours istanbul.

Even in Italy, before the great cities had crushed the feudal-lords and had forced them to become citizens, the mediaeval cities had constantly to fight for their existence against chiefs whose castles lay within sight. The ancient city was a State — the collective centre of an organised territory, supreme within it, and owing no fealty to any other sovereign, temporal or spiritual, outside its own territory. The mediaeval city was only a privileged town within a fief or kingdom, having charters, rights, and fortifications of its own; but, both in religious and in political rank, bound in absolute duty to far distant and much more exalted superiors.

Defensive system vastly more elaborate

Partly as a consequence of its being in constant danger from its neighbours, it had a defensive system vastly more elaborate than that of ancient cities. Its outer walls were of enormous height, thickness, and complexity. They were flanked with gigantic towers, gates, posterns, and watch-towers; it had a broad moat round ‘it and a complicated series of drawbridges, stockades, barbicans, and outworks. We may see something of it in the old city of Carcassonne in the south of France, destroyed by St. Louis in 1262, in the walls of Rome round the Vatican, and in the old walls of Constantinople on the western side near the Gate of St. Romanus. From without the Mediaeval City looked like a vast castle. And the military discipline and precautions were entirely those of a castle.

In peace or war, it was a fortress first, and a dwelling- place afterwards. This vast apparatus of defence cramped the space and shut out light, air, and prospect. Few ancient cities would have looked from without like a fortress; for the walls were much lower and simpler, in the absence of any elaborate system of artillery. But the Mediaeval City with its far loftier walls, towers, gates, and successive defences looked more like a prison than a town, and indeed to a great extent it was a prison.

There could seldom have been much prospect from within it, except of its own walls and towers; there were few open spaces, usually there was one small market-place, no public gardens or walks; the city was encumbered with castles, monasteries, and castellated enclosures; and the bridges and quays were crowded with a confused pile of lofty wooden houses; and, as the walls necessarily ran along any sea or river frontage that the city had, it was impossible to get any general view of the town, or to look up or down the river for the closely-packed buildings on the bridges.

0 notes

Photo

The Medieval City

We turn to imagine some city of the Middle Ages. Here also would be as in an ancient city, a long circuit of walls, with gates and towers, a military and highly organised society, a complex religious system, intense civic pride and patriotism. And yet the differences are vast. The grand difference of all is that the city is no longer the State, except in some parts of Italy, and even there not in the early Middle Ages. In the early Middle Ages, the city is not the State or the nation: it is only a stronghold, or fortified magazine in the barony, duchy, kingdom, or empire.

It is only a big and very complicated castle, with its defensive system exactly like any other castle, governed by a mayor, bailiff, or prior, and the burgher council, and not necessarily by a feudal lord. Except in Italy and a few free towns along the Mediterranean at particular periods, no city counted itself as wholly outside the jurisdiction of some overlord, king, or emperor.

Apart from its political and legal privileges, a mediaeval city was something like Windsor Castle or the Tower of London, on a large scale and with many subdivisions, governed by an elected corporation and not by a baron or viceroy. The ancient city, however much it had to fear war and opposition from its rival cities or states, could feel safe within its own territories from any attack on the part of its rural neighbours, subjects, or fellow-citizens. There it was mistress, or rather the city included the territory around it. No Athenian ever dreamed of being invaded by the inhabitants of Attica, or even of Boeotia. No Roman troubled himself about Latians or Etruscans other than the citizens of Latian or Tuscan cities. City life in the Middle Ages was a very different thing. Until a mediaeval city became very strong and had secured round itself an ample territory, it was always in difficulties with the lords of neighbouring fiefs and castles city tours istanbul.

Even in Italy, before the great cities had crushed the feudal-lords and had forced them to become citizens, the mediaeval cities had constantly to fight for their existence against chiefs whose castles lay within sight. The ancient city was a State — the collective centre of an organised territory, supreme within it, and owing no fealty to any other sovereign, temporal or spiritual, outside its own territory. The mediaeval city was only a privileged town within a fief or kingdom, having charters, rights, and fortifications of its own; but, both in religious and in political rank, bound in absolute duty to far distant and much more exalted superiors.

Defensive system vastly more elaborate

Partly as a consequence of its being in constant danger from its neighbours, it had a defensive system vastly more elaborate than that of ancient cities. Its outer walls were of enormous height, thickness, and complexity. They were flanked with gigantic towers, gates, posterns, and watch-towers; it had a broad moat round ‘it and a complicated series of drawbridges, stockades, barbicans, and outworks. We may see something of it in the old city of Carcassonne in the south of France, destroyed by St. Louis in 1262, in the walls of Rome round the Vatican, and in the old walls of Constantinople on the western side near the Gate of St. Romanus. From without the Mediaeval City looked like a vast castle. And the military discipline and precautions were entirely those of a castle.

In peace or war, it was a fortress first, and a dwelling- place afterwards. This vast apparatus of defence cramped the space and shut out light, air, and prospect. Few ancient cities would have looked from without like a fortress; for the walls were much lower and simpler, in the absence of any elaborate system of artillery. But the Mediaeval City with its far loftier walls, towers, gates, and successive defences looked more like a prison than a town, and indeed to a great extent it was a prison.

There could seldom have been much prospect from within it, except of its own walls and towers; there were few open spaces, usually there was one small market-place, no public gardens or walks; the city was encumbered with castles, monasteries, and castellated enclosures; and the bridges and quays were crowded with a confused pile of lofty wooden houses; and, as the walls necessarily ran along any sea or river frontage that the city had, it was impossible to get any general view of the town, or to look up or down the river for the closely-packed buildings on the bridges.

0 notes

Photo

The Medieval City

We turn to imagine some city of the Middle Ages. Here also would be as in an ancient city, a long circuit of walls, with gates and towers, a military and highly organised society, a complex religious system, intense civic pride and patriotism. And yet the differences are vast. The grand difference of all is that the city is no longer the State, except in some parts of Italy, and even there not in the early Middle Ages. In the early Middle Ages, the city is not the State or the nation: it is only a stronghold, or fortified magazine in the barony, duchy, kingdom, or empire.

It is only a big and very complicated castle, with its defensive system exactly like any other castle, governed by a mayor, bailiff, or prior, and the burgher council, and not necessarily by a feudal lord. Except in Italy and a few free towns along the Mediterranean at particular periods, no city counted itself as wholly outside the jurisdiction of some overlord, king, or emperor.

Apart from its political and legal privileges, a mediaeval city was something like Windsor Castle or the Tower of London, on a large scale and with many subdivisions, governed by an elected corporation and not by a baron or viceroy. The ancient city, however much it had to fear war and opposition from its rival cities or states, could feel safe within its own territories from any attack on the part of its rural neighbours, subjects, or fellow-citizens. There it was mistress, or rather the city included the territory around it. No Athenian ever dreamed of being invaded by the inhabitants of Attica, or even of Boeotia. No Roman troubled himself about Latians or Etruscans other than the citizens of Latian or Tuscan cities. City life in the Middle Ages was a very different thing. Until a mediaeval city became very strong and had secured round itself an ample territory, it was always in difficulties with the lords of neighbouring fiefs and castles city tours istanbul.

Even in Italy, before the great cities had crushed the feudal-lords and had forced them to become citizens, the mediaeval cities had constantly to fight for their existence against chiefs whose castles lay within sight. The ancient city was a State — the collective centre of an organised territory, supreme within it, and owing no fealty to any other sovereign, temporal or spiritual, outside its own territory. The mediaeval city was only a privileged town within a fief or kingdom, having charters, rights, and fortifications of its own; but, both in religious and in political rank, bound in absolute duty to far distant and much more exalted superiors.

Defensive system vastly more elaborate

Partly as a consequence of its being in constant danger from its neighbours, it had a defensive system vastly more elaborate than that of ancient cities. Its outer walls were of enormous height, thickness, and complexity. They were flanked with gigantic towers, gates, posterns, and watch-towers; it had a broad moat round ‘it and a complicated series of drawbridges, stockades, barbicans, and outworks. We may see something of it in the old city of Carcassonne in the south of France, destroyed by St. Louis in 1262, in the walls of Rome round the Vatican, and in the old walls of Constantinople on the western side near the Gate of St. Romanus. From without the Mediaeval City looked like a vast castle. And the military discipline and precautions were entirely those of a castle.

In peace or war, it was a fortress first, and a dwelling- place afterwards. This vast apparatus of defence cramped the space and shut out light, air, and prospect. Few ancient cities would have looked from without like a fortress; for the walls were much lower and simpler, in the absence of any elaborate system of artillery. But the Mediaeval City with its far loftier walls, towers, gates, and successive defences looked more like a prison than a town, and indeed to a great extent it was a prison.

There could seldom have been much prospect from within it, except of its own walls and towers; there were few open spaces, usually there was one small market-place, no public gardens or walks; the city was encumbered with castles, monasteries, and castellated enclosures; and the bridges and quays were crowded with a confused pile of lofty wooden houses; and, as the walls necessarily ran along any sea or river frontage that the city had, it was impossible to get any general view of the town, or to look up or down the river for the closely-packed buildings on the bridges.

0 notes

Photo

The Medieval City

We turn to imagine some city of the Middle Ages. Here also would be as in an ancient city, a long circuit of walls, with gates and towers, a military and highly organised society, a complex religious system, intense civic pride and patriotism. And yet the differences are vast. The grand difference of all is that the city is no longer the State, except in some parts of Italy, and even there not in the early Middle Ages. In the early Middle Ages, the city is not the State or the nation: it is only a stronghold, or fortified magazine in the barony, duchy, kingdom, or empire.

It is only a big and very complicated castle, with its defensive system exactly like any other castle, governed by a mayor, bailiff, or prior, and the burgher council, and not necessarily by a feudal lord. Except in Italy and a few free towns along the Mediterranean at particular periods, no city counted itself as wholly outside the jurisdiction of some overlord, king, or emperor.

Apart from its political and legal privileges, a mediaeval city was something like Windsor Castle or the Tower of London, on a large scale and with many subdivisions, governed by an elected corporation and not by a baron or viceroy. The ancient city, however much it had to fear war and opposition from its rival cities or states, could feel safe within its own territories from any attack on the part of its rural neighbours, subjects, or fellow-citizens. There it was mistress, or rather the city included the territory around it. No Athenian ever dreamed of being invaded by the inhabitants of Attica, or even of Boeotia. No Roman troubled himself about Latians or Etruscans other than the citizens of Latian or Tuscan cities. City life in the Middle Ages was a very different thing. Until a mediaeval city became very strong and had secured round itself an ample territory, it was always in difficulties with the lords of neighbouring fiefs and castles city tours istanbul.

Even in Italy, before the great cities had crushed the feudal-lords and had forced them to become citizens, the mediaeval cities had constantly to fight for their existence against chiefs whose castles lay within sight. The ancient city was a State — the collective centre of an organised territory, supreme within it, and owing no fealty to any other sovereign, temporal or spiritual, outside its own territory. The mediaeval city was only a privileged town within a fief or kingdom, having charters, rights, and fortifications of its own; but, both in religious and in political rank, bound in absolute duty to far distant and much more exalted superiors.

Defensive system vastly more elaborate

Partly as a consequence of its being in constant danger from its neighbours, it had a defensive system vastly more elaborate than that of ancient cities. Its outer walls were of enormous height, thickness, and complexity. They were flanked with gigantic towers, gates, posterns, and watch-towers; it had a broad moat round ‘it and a complicated series of drawbridges, stockades, barbicans, and outworks. We may see something of it in the old city of Carcassonne in the south of France, destroyed by St. Louis in 1262, in the walls of Rome round the Vatican, and in the old walls of Constantinople on the western side near the Gate of St. Romanus. From without the Mediaeval City looked like a vast castle. And the military discipline and precautions were entirely those of a castle.

In peace or war, it was a fortress first, and a dwelling- place afterwards. This vast apparatus of defence cramped the space and shut out light, air, and prospect. Few ancient cities would have looked from without like a fortress; for the walls were much lower and simpler, in the absence of any elaborate system of artillery. But the Mediaeval City with its far loftier walls, towers, gates, and successive defences looked more like a prison than a town, and indeed to a great extent it was a prison.

There could seldom have been much prospect from within it, except of its own walls and towers; there were few open spaces, usually there was one small market-place, no public gardens or walks; the city was encumbered with castles, monasteries, and castellated enclosures; and the bridges and quays were crowded with a confused pile of lofty wooden houses; and, as the walls necessarily ran along any sea or river frontage that the city had, it was impossible to get any general view of the town, or to look up or down the river for the closely-packed buildings on the bridges.

0 notes

Text

The Charles Bridge at dawn, Prague, Czech Republic

#prague#charles bridge#dawn#statues#bridge#lanterns#bohemia#czech republic#photograph#photography#europe#european#vltava river#gothic#architecture#baroque#city#atmosperic#sculptures#medieval#central europe

4K notes

·

View notes

Text

Clay Figure of Warrior from Xochicalco, Mexico dated between 650 - 900 on display at the National Museum of Anthropology in Mexico City, Mexico

Photographs taken by myself 2023

#military history#art#archaeology#fashion#armour#mexico#mexican#medieval#national museum of anthropology#mexico city

172 notes

·

View notes

Text

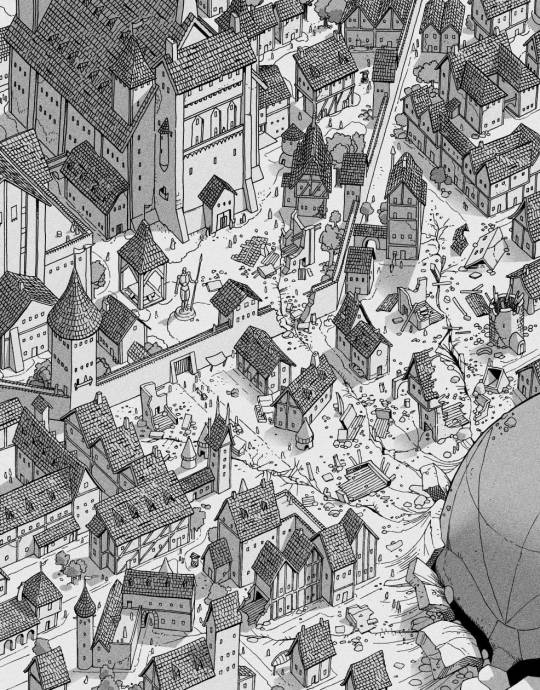

The city of Graben

Another page for the fantasy journal book. Sketch wip pics here!

Kickstarter link

#art#ink#drawing#illustration#fantasy#rpg#ttrpg#dnd#map#city#medieval#Yes this took absolutely forever to draw!#isometric

506 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tallinn, Estonia

Taken May 2024

#ueswv#estonia#baltics#churches#statues#medieval architecture#street art#harbors#cities#my photos#my places

105 notes

·

View notes