#The Illustrated Library of the Natural Sciences (1958)

Text

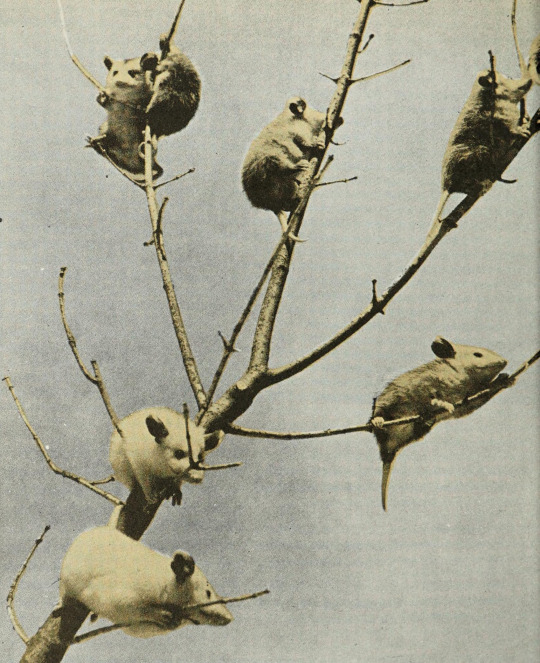

A tree full of baby opossums

By: Charles Philip Fox

From: The Illustrated Library of the Natural Sciences

1958

#virginia opossum#opossum#marsupial#mammal#1958#1950s#Charles Philip Fox#The Illustrated Library of the Natural Sciences

3K notes

·

View notes

Photo

Verill’s two-spot octopus

By: Woody Williams

From: The Illustrated Library of the Natural Sciences

1958

#scientific illustration#octopus#cephalopod#sea creatures#woody williams#Illustration#animal kingdom

99 notes

·

View notes

Text

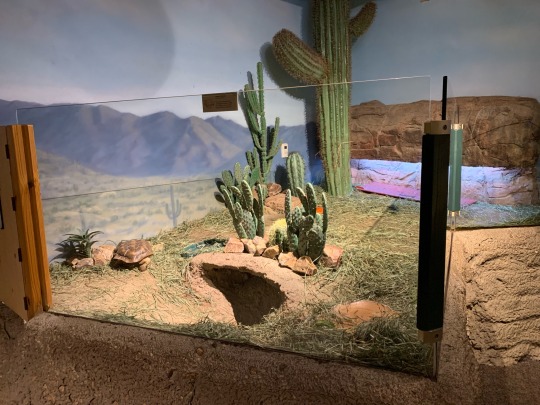

Overlooked Collections 6: Boonshoft Museum of Discovery

The next museum I’m focusing on in this series is the Boonshoft Museum of Discovery, which I visited last month on a trip to Ohio with @kaijutegu . The Boonshoft is notable for being the only zoo, aquarium, planetarium, or science center in the city of Dayton. I consider it to be an overlooked collection since Dayton is an overlooked city as a whole despite being Ohio’s fourth largest metropolitan area.

Location: Dayton, OH, USA

Admission: $14.50 for adults, $12.50 for seniors 60+, $11.50 for children 3-17. Members and children under 3 are admitted for free. Discounts are available for AAA members, State Farm insurance members, Culture Works cardholders, and active military. They also have a robust reciprocal admission program, I was able to get free admission with my Field Museum membership.

Covid-19 Operations: At the time of my visit masks were strongly recommended but not required for all visitors, currently masks are required for all visitors and staff. All exhibit spaces have reopened and high touch areas are regularly sanitized.

Date of Opening: 1893 as a part of the Dayton Public Library and Museum. Renamed the Dayton Museum of Natural History in 1952, moved to the current building in 1958, renamed the Boonshoft Museum of Discovery in January 1999.

Date of Visit: September 14th, 2021.

Overview: The Boonshoft Museum of Discovery is a children’s museum, science center, and zoo located in Dayton, Ohio. Originally opened as a natural history museum it merged with a proposed children’s museum in 1996. The museum has a broad scope that includes earth sciences, paleontology, biology, physics, anthropology, and astronomy. The museum also features a “play zoo” and is one of six facilities in Ohio currently accredited by the Association of Zoos and Aquariums (AZA). The SunWatch Indian Village/Archaeological Park is affiliated with the Boonshoft and is governed by the same organization, the Dayton Society of Natural History.

Permanent exhibits: Splash! Exploring Water in the Miami Valley Region, Science on a Sphere, Hall of the Universe, Oscar Boonshoft Science Central, Discovery Zoo, MeadWestvaco Treehouse, Explorers Crossing, Sonoran Desert, Strictly Briks at the Boonshoft Museum, Bieser Discovery Center, Kids Place

Special exhibits: Collections A to Z: Explore the World in Dayton. No opening or closing dates are given.

Strengths: Many of the exhibits have interactive elements which makes them appealing to children. Signage wasn’t too wordy and featured illustrations, photographs, and other graphics. The live animal exhibits were all spacious and appropriate for the species living in them. The display for the museum’s mummy was very thoughtful and contained accurate information and reconstructions.

Weaknesses: The museum definitely skews heavily towards children so there aren’t as many exhibits that adults might find interesting. The other anthropology displays could have used more up to date information and attribution/collection information. Some interactive displays were having technical issues during my visit.

Notable pieces/displays: The otter, kinkajou, and meerkat exhibits in the Discovery Zoo. The Treehouse as an exhibit concept.

Pictures (image descriptions needed):

#overlooked collections#Boonshoft Museum of Discovery#museums#children’s museum#zoo animals#anthropology#paleontology#geology

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Paul Rudolph Architect: Modern US Architecture

Paul Rudolph, Architect, American Building, US Design Studio, Yale, Asian Projects, Office

Paul Rudolph Architect : Architecture

20th Century Architect Practice, USA – Building Design Information

Nov 11, 2020

Visualization of Paul Rudolph’s Gatot Subroto (Jakarta 1990, unbuilt):

The Gatot Subroto was an 87500 square meter office condominium complex of eight towers designed for Jakarta, Indonesia by American Architect Paul Rudolph. The design includes many “green” sustainability features that were new to the world of architecture in 1990.

Each three story block was separated from the next by a void deck, an outdoor space intended to be planted as a sky garden; making the total added green space larger than the footprint of the building itself! The visualization process is iterative, and this is an interim view of the building, with some details yet to be addressed.

Oct 29 + 25 + 22, 2020

Paul Rudolph’s undiscovered buildings

Collaborating with premier Architectural Visualization Studio Design Distill, Paul Rudolph’s unknown late designs to be brought to life

Latest visualization of Gatot Subroto in Jakarta, Indonesia:

image courtesy of: Architectural Visualization Studio Design Distill

New visualization of Gatot Subroto in Jakarta, Indonesia:

image courtesy of: Architectural Visualization Studio Design Distill

Over the past several years Eric Wolff has been researching Paul Rudolph’s archives to understand his late-career works in Asia. Scholars have described Rudolph’s late works as “seven buildings including a couple of villas”.

image courtesy of: Library of Congress, photographer unknown

Eric’s research has uncovered a very different narrative about Rudolph. In Asia, Rudolph designed more than 20 buildings and participated in more than 50 projects during his late career (1978 – 1997). These “unknown” designs are amongst his finest, most refined, and most ambitious. Based on the research of 1000s of items from Rudolph’s archives digital models were created of Rudolph’s “unbuilt” late designs.

Sketch by Paul Rudolph of his Gatot Subroto, Jakarta, Indonesia:

image courtesy of: Library of Congress, digital pictures courtesy of Eric Wolff

To illustrate the design of Paul Rudolph’s Gatot Subroto (unbuilt, Jakarta 1990) an exciting collaboration with Design Distill was born. “Design Distill is a multidisciplinary group that has the passion, talents and capabilities to translate my research of Paul Rudolph’s late works into visualizations, bringing the buildings to life so they can be evaluated and celebrated.” Eric Wolff, Researcher and Author.

Model of Paul Rudolph’s Gatot Subroto, Jakarta, Indonesia:

images courtesy of: Library of Congress, digital pictures courtesy of Eric Wolff

Design Distill a visualization studio that narrates design projects. They are about the creative communication of architecture, urban design, landscape architecture, real estate development and digital media. “I was intrigued and surprised by the sheer volume of designs Paul Rudolph had completed in his late career in Asia. It was a natural fit for Design Distill to be the collaboration partner in this project; we are enthusiastic with the challenge to capture and illustrate the sculptural complexity of Rudolph’s Gatot Subroto” Andrew Hartness, Principal Design Distill.

image courtesy of: Library of Congress, digital picture courtesy of Eric Wolff

The Gatot Subroto an 87,500 m2 office condominium complex was a client request for eight office towers of varying foot prints to be an office condominium complex, where the Dharmala group would occupy the main tower and the seven towers rented to prime tenants. Rudolph’s final design was a masterpiece; not only because he met the customer brief, but he also created a sustainable building far before it was fashionable.

Visualization of Gatot Subroto, Jakarta, Indonesia:

image courtesy of: Architectural Visualization Studio Design Distill

Kickstarter to fund the visualization project: Illustrating Paul Rudolph’s undiscovered buildings

For information on Paul Rudolph and his works: https://www.paulrudolphheritagefoundation.org

Paul Rudolph – Key Projects

Jan 31, 2020

Walker Guest House, Palm Spings, California, USA

Design: Paul Rudolph Architect

photo : Anton Grassl, Esto, courtesy Sarasota Architectural Foundation

Walker Guest House by Paul Rudolph

Featured Buildings by Paul Rudolph, alphabetical:

Burroughs Wellcome headquarters, North Carolina, USA

Dates built: 1969; 1980

The Burroughs Wellcome Fund (BWF) is a private, independent biomedical research foundation based in Research Triangle Park.

In 1969 pharmaceuticals giant Burroughs-Wellcome commissioned Paul Rudolph to design its headquarters in Research Triangle Park, NC, an area between Raleigh and Durham dominated by high-tech corporate research facilities.

The building was expanded by Rudolph in the 1980s and a covenant prevented unauthorized changes during his lifetime. After a series of mergers, Burroughs became GlaxoSmithKline, which sold the 700,000 square foot facility.

The new owners, United Therapeutics, describe themselves as admirers of this Modern architect and plan to retain what they consider ‘historically important’ parts of the complex and demolish others, presumably the 1980s expansion.

BWF was founded in 1955 as the corporate foundation of the Burroughs Wellcome Co., the U.S. branch of the Wellcome pharmaceutical enterprise, based in the United Kingdom. In 1993, a $400 million gift from the Wellcome Trust enabled BWF to become fully independent from the company, which was acquired by Glaxo in 1995 and is now known as GlaxoSmithKline.

BWF is one of the most significant funders of biomedical research. Its overall goal is to help scientists early in their careers develop as independent investigators, and to advance fields in the basic medical sciences that are undervalued or in need of particular encouragement.

source: https://ift.tt/37C6S0O

Riverview High School, Sarasota, Florida, USA

Dates built: 1957-58

was under threat for demolition in (early) 2007

Riverview High School – redevelopment, Sarasota, Florida

Date built: 2007-

Architecture Competition: Shortlist of 5 incl. RMJM Hillier and John McAslan & Partners

Riverview High School is a four-year comprehensive public high school in Sarasota, Florida, United States. Riverview educates students from ninth grade to twelfth grade. The school has 2,654 students and 161 teachers. The school’s mascot is the ram. As of the 2012-2013 school year, it is the largest school in the county.

Notable programs at the school include the International Baccalaureate Program, a rigorous regimen that prepares its candidates on an international rubric and prepares them for further education; a Chamber Choir that has performed in Europe and New York’s Carnegie Hall; and the Riverview High School Kiltie Band, a group of about 220 musicians that has marched three times in the Macy’s Thanksgiving Day parade and has traveled to perform in Ireland, California, and many other places.

The Rudolph building, 1958-2009

Riverview’s old main building opened in 1958, and included a planetarium. The main building was designed by noted International Style architect Paul Rudolph, dean of the Yale School of Architecture. While Rudolph was later associated with the architectural style Brutalism, Riverview was in the International Style. It was one of the best-known structures associated with the Sarasota School of Architecture, sometimes referred to as Sarasota Modern.

source: https://ift.tt/2IK9jUL

Yale Arts Complex – Paul Rudolph Hall at Yale University, USA

Date built: 1963

photo : Peter Aaron

Paul Rudolph Hall

The 114,000 square foot building, constructed of cast-in-place concrete in the Brutalist style, was formerly known as the Art and Architecture Building.

It was designed by then chair of the Department of Architecture, Paul Rudolph and completed in 1963.

More Paul Rudolph buildings online soon

Location: Elkton, Kentucky, USA

Paul Rudolph Practice Information

Architect studio was based in USA

American Architects

Paul Rudolph Foundation

This preservation and 501(c)3 nonprofit organization, is based in New York City. Founded in 2002, its mission is to facilitate the preservation and maintenance of the remaining structures designed by Paul Rudolph through education, advocacy, preservation easements and technical services.

The Collections & Library

The Foundation owns, maintains, and is developing a collection of information on Paul Rudolph including press clippings, books, and various tangible and digital materials about or relating to Mr. Rudolph’s own work, influences and the contemporary cultural context in which he lived and worked. The Foundation has begun to digitally preserve a selection of photographs and articles related to Mr. Rudolph. The Foundation, pending further financial support, will professionally document, categorize, and present this and additional material in a cohesive manner for study by students, scholars, and the general public.

Phone:

212.223.7479

Address:

c/o George Balle

150 East 57th Street, #26-B

New York, NY 10022

United States

source: https://ift.tt/2gfc9Tm

20th Century Architecture

Modern Architects

Modern Architecture

Modern Architecture Photos

Contemporary Architects

US Architecture

Contemporary Architecture in USA

American Architecture

New York Architecture

Architectural Tours

Modern Houses

Modern Housing

Architecture Studios

Buildings / photos for the Paul Rudolph page welcome

Website: Building

The post Paul Rudolph Architect: Modern US Architecture appeared first on e-architect.

1 note

·

View note

Text

An Illustrated Field Guide to the Art, Science, and Joy of Tea

An Illustrated Field Guide to the Art, Science, and Joy of Tea

https://ift.tt/2pYFGCp

From leaf to cup, by way of the history of human civilization.

“The first sip is joy, the second is gladness, the third is serenity, the fourth is madness, the fifth is ecstasy,” Jack Kerouac wrote of tea in his 1958 novel The Dharma Bums. Late one night that year, he walked five miles with an enormous tape recorder strapped to his back to keep the woman he loved from taking her own life.

Lois Beckwith didn’t die that night. She and Jack soon parted ways as lovers, but remained friends. Eventually, he introduced her to the man who would become her husband. Their son would go on to devote his life to tea.

In Pursuit of Tea founder Sebastian Beckwith fell in love with tea while working as a trekking guide in Bhutan and northern India in the 1980s, and has spent the years since procuring and advocating for the planet’s finest, most sustainably grown and ethically harvested teas. Traveling to and working with small farms in Asia’s most historic tea-growing regions, he sources teas that grace the menus of some of New York City’s finest restaurants and have powered much of my own writing over the years. In his workshops, seminars, and lectures, he has brought the art-science of tea to the American Museum of Natural History, the French Culinary Institute, and Columbia University.

Now, Beckwith harvests the wisdom of his life’s work in A Little Tea Book: All the Essentials from Leaf to Cup (public library) — part practical field guide to choosing, preparing, and enjoying tea, part love letter, co-written with his childhood friend, former firefighter, and Gutsy Girl author Caroline Paul, and splendidly illustrated by Caroline’s wife and my dear friend Wendy MacNaughton.

Radiating from the pages are deep knowledge, good-natured humor, and a largehearted love of tea — the plant, the experience, the ecosystem of botany and labor and ritual, which George Orwell considered “one of the main stays of civilization.” What emerges is an encyclopedia of fact and joy, delving into the cultural and political histories of tea alongside its practical science and daily delights, bridging the sensorial and the spiritual dimensions of this ancient tradition turned modern staple.

Punctuating the book are various curiosities from the history of tea, emanating broader insight into human culture, the nature of creativity, and the serendipitous, often haphazard ways in which new ideas take root. Take, for instance, the story of the tea bag:

Tea bags were invented in the late 1800s but became wildly popular only after a New York tea purveyor named Thomas Sullivan sent samples of tea in silk bags. These were intended to be opened, the tea emptied out and then brewed, but customers instead dropped the bags straight into the water — and then complained that the material did not allow for the tea to steep. Sullivan turned to a more porous cloth and the tea bag was quickly embraced in America (though most of Britain turned up its nose, using loose tea until the mid-1970s.)

There are also invaluable antidotes to various oft-repeated myths, misconceptions, and half-truths — from the elemental fact that the six basic types of tea (white, green, yellow, oolong, black, and dark) all come from a single plant, Camellia sinensis, to the complex matter of caffeine. Beckwith and Paul offer a scientific corrective:

Many of us drink tea to wake up at the beginning of our day. You may even have heard that Camellia sinensis contains more caffeine than coffee beans. This is true, but misleading. We use much less tea than coffee by weight for a serving, so your cup of tea actually has at most one half the amount of caffeine as a cup of coffee. The relative level varies depending on the leaf used (the buds have higher concentrations), the cultivar, the leaf shape (a larger leaf results in a slower infusion because there is less surface area than, say, a fanning tea grade in your cup), and the brew time and technique (since caffeine is water-soluble, the longer tea steeps, the more caffeine is extracted; powdered tea like matcha has more caffeine because the leaves are consumed, not infused). It is important to note that caffeine does not correspond with tea type, so one cannot categorically say that black tea has more than green, or yellow tea has more than white.

Tea also contains the unique calming and relaxing — but not sedative — amino acid theanine, which has been found only in Camellia sinensis and one mushroom, Boletus badius. Theanine has been shown to improve mood and increase focus when combined with caffeine. This may be why tea drinkers often avoid the anxiety and jitters of those who imbibe coffee (known to some of us tea lovers as “devil juice.”)

Complement the lovely Little Tea Book with Orwell’s eleven golden rules for making the perfect cup of tea and the MacNaughton-illustrated field guide to wine, then revisit the touching, improbable story of how Kerouac saved Beckwith’s mother’s life.

donating = loving

Bringing you (ad-free) Brain Pickings takes me hundreds of hours each month. If you find any joy and stimulation here, please consider becoming a Supporting Member with a recurring monthly donation of your choosing, between a cup of tea and a good dinner.

newsletter

Brain Pickings has a free weekly newsletter. It comes out on Sundays and offers the week’s most unmissable reads. Here’s what to expect. Like? Sign up.

via Brain Pickings https://ift.tt/1LkXywO

October 16, 2018 at 03:47PM

0 notes

Text

Are rightsholders ready for public domain day?

Dave Davis Contributor

Dave Davis joined Copyright Clearance Center in 1994 and currently serves as a research analyst. He previously held directorships in both public libraries and corporate libraries and earned joint master’s degrees in Library and Information Sciences and Medieval European History from Catholic University of America.

More posts by this contributor

A long and winding road to new copyright legislation

How AI and copyright would work

On January 1, 2019, the New Year will ring in untold numbers of additions to the public domain in the U.S., including hundreds and maybe thousands of works with at least a small public reputation. This, of course, is due to the expiration of the terms of their copyrights, some of which have been extended multiple times since the 1960s.

This is a good thing from many perspectives, including that of authors, publishers, museum curators, teachers, old-book readers and music and film buffs. It possibly may be a slightly bad thing for a few people — primarily certain estates representing long-dead authors and other creators.

What’s a “term” in the context of copyright?

The duration, or term, of U.S. copyright is set by Congress, and has gradually crept up over time from the original 14 years (plus 14 more if the author was still alive and renewed the copyright) — in Thomas Jefferson’s time — to a whopping “life of the author plus 70 years,” as set by the 1998 “Copyright Term Extension Act” (CTEA, which extended it from life plus 50).

For works first published between 1909 and 1978, the maximum term was finally set by Congress at 95 years (assuming the author complied with a whole lot of rules, alluded to below). And for post-1978 works, in instances where the author/creator is not a human being (such as a business commissioning a “work made for hire” under rules developed in the case-law) or the work was published under a pseudonym for an unknown person, the term can be as long as 120 years! The copyright in a work, duly registered at the time that registration was required (pre-1978), may never have been renewed, and so its protection may have quietly lapsed some time ago; for many more obscure works, it’s hard to know.

Fun fact: This Copyright Term Extension Act is also known as the Sonny Bono Copyright Term Extension Act. Congress named it in memory of the composer of “I’ve Got You, Babe,” who, as a member of Congress from Southern California, was among the authors of the bill; he unfortunately happened to die while it was being worked on in committee. Prior to 1978, the term of U.S. copyrights was determined by fixed terms of years, subject to publication, registration and notice requirements. Here are more details on that.

How do works pass into the public domain?

Currently, works pass into the public domain according to a complex schedule, combining (sometimes awkwardly) the rules of various laws implemented over the past century.

Bear in mind, however, that many works have passed (or “fallen” or “lapsed,” as the older phrases had it) into the public domain in the U.S. for reasons other than term expiry, even during the 20 years of the CTEA extension. According to the law in effect prior to 1978, if the work was published but never registered in the U.S. Copyright Office, it did not receive protection under copyright law; a work might also not be protected by U.S. copyright law if it lacked proper notice — the © symbol and the proper wording — or if the work’s registration was not renewed after its first 28-year term expired. Or if, as a work of the federal government, it never enjoyed copyright protection in the first place.

Qui Bono? (get it?)

As it turns out, it is not just re-publishers of “classic” texts, such as Dover Thrift Editions, which benefit when new works become available. Textbook and educational publishers frequently re-use old short stories and essays in larger collections, and a work of marginal utility might become more attractive as a potential addition to these collections once the cost of clearing the rights is reduced.

For example, a few years ago a 1922 story by F. Scott Fitzgerald, “The Curious Case of Benjamin Button,” (whose U.S. copyright had lapsed) was adapted into a feature film. To me, the lesson to be gleaned is that many works of the early 20th century still appear to bear some cultural cachet (or at least continuing value to society) — such that more no-cost access to these works (by their passing from copyright protection to the public domain) should have the overall effect of helping them find new audiences.

Note: Bear in mind, all of these examples are simply illustrative — without a full and careful copyright search, it is difficult to be certain of the copyright status of almost any work. On that, more below.

New works coming into the U.S. public domain also will have the effect of giving researchers new texts to run Text and Data Mining (TDM) algorithms across. It also may add to the richness of film and cultural studies.

Mark Twain proves this isn’t so easy

Unfortunately, determining when a work has in fact “fallen” into the public domain due to the term of its copyright having expired is not always as simple as one might hope.

For example, one might think that everything ever laid down by the pen of Mark Twain (S.L. Clemens, d. 1910) would be in the public domain by now. But, since he left a treasure trove of unpublished works, their copyright protection has extended for many years after his death, because, under pre-1978 law, those works’ copyright protection would not start until the works were published. The distinction between published and unpublished works has been discarded under post-1978 law, but won’t be fully effective for another 30 years. So, some items in the microfilm edition of Twain’s letters and manuscripts (their first publication) are still considered to be under copyright. He’s also enjoyed considerable success recently with the full and final publication of his autobiography.

Twain, a student of intellectual property, steadfastly argued for a perpetual copyright, but he came to realize that this was not permitted under the copyright clause of the U.S. Constitution, which refers to “securing [protection] for limited times.” But, in an age when copyright only protected works for which registrations had been obtained, he did point out that most books wouldn’t be affected by a longer term at all — for the vast bulk of them had no commercial life remaining to them a very few years after their initial publication:

One author per year produces a book which can outlive the forty-two-year limit; that’s all. This nation can’t produce two authors a year that can do it; the thing is demonstrably impossible. All that the limited copyright can do is to take the bread out of the mouths of the children of that one author per year.

I made an estimate some years ago, when I appeared before a committee of the House of Lords, that we had published in this country since the Declaration of Independence 220,000 books. They have all gone. They had all perished before they were ten years old. It is only one book in 1000 that can outlive the forty-two-year limit. Therefore, why put a limit at all? You might as well limit the family to twenty-two children.

– S.L. Clemens, in testimony to Congress, concerning proposed copyright legislation (1906)

“Forever minus a day,” another idea which has been occasionally bruited about (particularly by Congressman Bono and his widow, who was later elected seven times in her own right to Congress), would not constitute much of an effective limit, and so would, I believe, violate the Constitutional limitation; 95 years (an estimated average of the “Life plus 70” term) seems closer to a natural lifespan for a copyright — to me at least. If you and your heirs somehow can’t get the commercial value out of your work before nearly a century is out, I think there’s a takeaway lesson there.

On the other hand…

… some works do have cultural lifespans exceeding the term of copyright. The estates of certain literary, film and musical creators may stand to lose when the copyright in some of the works in their respective repertories lose copyright protection due to the lapse of their terms. For some examples of works entering the public domain on January 1, 2019, that may still have financial value to the author/creator’s heirs: Hemingway’s “Three Stories and 10 Poems” was first published in 1923; it was also the year of release for “Safety Last!” a silent film from Hal Roach Studios, starring Harold Lloyd, which many people remember. The same year saw the first publication (of the sheet music) for “Who’s Sorry Now?” which was a hit recording for Connie Francis in 1958.

But, on balance, “Nothing gold can stay,” as Robert Frost observed in a poem slated — I’m pretty sure — to enter the public domain on January 1st.* The reading, listening, and viewing public should expect to be the main beneficiary of these works entering the public domain. Indeed, 95 years is a good run for the commercial exploitation of a work. Now it’s everybody else’s turn to benefit.

*If it hasn’t already. Copyright searches, on the detail level, can be quite difficult and time-consuming. See: https://www.copyright.gov/rrc/. For any proposed commercial republication, it is certainly the course of wisdom to consult with an attorney and have a full copyright search done.

Are rightsholders ready for public domain day? published first on https://timloewe.tumblr.com/

0 notes

Text

Sword and Sorcery Artists: Wayne Barlowe

Wayne Barlowe (b. 1958) has had a very successful career in science fiction illustration. He has also done some fantasy work.

From his website:

“Born in Glen Cove, New York to well-known natural history artists Sy and Dorothea Barlowe, Wayne Douglas Barlowe attended the Art Students League and The Cooper Union in New York City. While in college he apprenticed in the Exhibition Department of The American Museum of Natural History. During this period Barlowe collaborated with his parents on his first professional book assignment, the Instant Nature Guide to Insects (Grossett & Dunlop). Wayne’s sister, Amy, is an acclaimed performer and composer of contemporary classical music.

In 1979 his first self-generated book, Barlowe’s Guide to Extraterrestrials, was published by Workman Publishing. The Guide, which Barlowe conceived, illustrated and co-authored, was nominated for The American Book Award and the science fiction community’s prestigious Hugo. It was chosen Best Illustrated Book of 1979 by the Locus Poll, and a Best Book For Young People by the American Library Association. The Guide, considered by many to be a contemporary classic SF work, sold nearly 400,000 copies worldwide in multiple languages.

Barlowe spent eight years creating over 300 book and magazine covers and illustrations for every major publisher as well as editorial paintings for Life, Time and Newsweek. His artwork has been seen on television on Walter Cronkhite’s Universe and Connie Chung’s Saturday Night as well as on the Discovery Channel. An interview with Barlowe appeared on the Sci-Fi Channel’s Inside Space program. Portfolios and interviews in print have appeared in TV Guide, Starlog, Realms of Fantasy, Science Fiction Age, Starburst, TV ZONE (UK), Filmfax, ImagineFX and The Idler.”

His first published work appears to be for Gregg Press hardback editions of Fritz Leiber’s “Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser” series in late 1977. A version was used for Night’s Black Agents (Berkley Medallion, 1978). This was the first Fritz Leiber book I ever owned. I thought the cover to be very accurate and moody. It captures sword and sorcery fiction perfectly.

More fantasy followed with a paperback edition of Poul Anderson’s Three Hearts and Three Lions in 1978. Berkley was full into the late 1970s sword and sorcery boom. Ken Kelly was doing the Robert E. Howard paperbacks, Barlowe appears to have gotten the other books. Berkley collected the second trilogy of Corum by Michael Moorcock in 1978.

Berkley had second editions of Norvell Page’s two novels about Prester John going back to the pulp era: Flame Winds (1978) and Sons of the Bear God (1979).

Berkley did a little bit of new fiction following on their reprints. Barlowe did the covers for Gerald Earl Bailey’s “Saga of Thorgrim:” Sword of the Nurlingas (1979) and Sword of Poyana (1979).

And that was it for sword and sorcery. Barlowe’s Guides to Extraterrestrials came out in 1979 and he was a hot artist for science fiction covers.

He did follow up in 1996 with Barlowe’s Guide to Fantasy, which I bought off the shelf when it came out. Barlowe illustrated both fantasy characters and creatures including Bran Mak Morn, Corum, etc.

Some of Barlowe’s work like the cover for The Chronicles of Corum is somewhat pedestrian. On the other hand his cover for Night’s Black Agents is a classic. Guess it is all what the editor or art director want.

Sword and Sorcery Artists: Wayne Barlowe published first on http://ift.tt/2zdiasi

0 notes

Video

youtube

Rachel Carson, Chapter 1

Rachel Louise Carson (May 27, 1907 – April 14, 1964) was an American marine biologist, author, and conservationist whose book Silent Spring and other writings are credited with advancing the global environmental movement.

Carson began her career as an aquatic biologist in the U.S. Bureau of Fisheries, and became a full-time nature writer in the 1950s. Her widely praised 1951 bestseller The Sea Around Us won her a U.S. National Book Award,[2] recognition as a gifted writer, and financial security. Her next book, The Edge of the Sea, and the reissued version of her first book, Under the Sea Wind, were also bestsellers. This sea trilogy explores the whole of ocean life from the shores to the depths.

Late in the 1950s, Carson turned her attention to conservation, especially some problems that she believed were caused by synthetic pesticides. The result was the book Silent Spring (1962), which brought environmental concerns to an unprecedented share of the American people. Although Silent Spring was met with fierce opposition by chemical companies, it spurred a reversal in national pesticide policy, which led to a nationwide ban on DDT and other pesticides. It also inspired a grassroots environmental movement that led to the creation of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.[3] Carson was posthumously awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by Jimmy Carter.

Silent Spring, Carson's most well-known book, was published by Houghton Mifflin on 27 September 1962.[29] The book described the harmful effects of pesticides on the environment, and is widely credited with helping launch the environmental movement.[30] Carson was not the first, or the only person to raise concerns about DDT,[31] but her combination of "scientific knowledge and poetic writing" reached a broad audience and helped to focus opposition to DDT use.[32] In 1994, an edition of Silent Spring was published with an introduction written by Vice President Al Gore.[33][34] In 2012 Silent Spring was designated a National Historic Chemical Landmark by the American Chemical Society for its role in the development of the modern environmental movement.[35]

Research and writing

Starting in the mid-1940s, Carson had become concerned about the use of synthetic pesticides, many of which had been developed through the military funding of science since World War II. It was the US federal government's 1957 gypsy moth eradication program, however, that prompted Carson to devote her research, and her next book, to pesticides and environmental poisons. The gypsy moth program involved aerial spraying of DDT and other pesticides (mixed with fuel oil), including the spraying of private land. Landowners on Long Island filed a suit to have the spraying stopped, and many in affected regions followed the case closely.[3] Though the suit was lost, the Supreme Court granted petitioners the right to gain injunctions against potential environmental damage in the future; this laid the basis for later successful environmental actions.[3][36][37]

The Audubon Naturalist Society also actively opposed such spraying programs, and recruited Carson to help make public the government's exact spraying practices and the related research.[38] Carson began the four-year project of what would become Silent Spring by gathering examples of environmental damage attributed to DDT. She also attempted to enlist others to join the cause: essayist E. B. White, and a number of journalists and scientists. By 1958, Carson had arranged a book deal, with plans to co-write with Newsweek science journalist Edwin Diamond. However, when The New Yorker commissioned a long and well-paid article on the topic from Carson, she began considering writing more than simply the introduction and conclusion as planned; soon it was a solo project. (Diamond would later write one of the harshest critiques of Silent Spring).[39]

As her research progressed, Carson found a sizable community of scientists who were documenting the physiological and environmental effects of pesticides.[3] She also took advantage of her personal connections with many government scientists, who supplied her with confidential information. From reading the scientific literature and interviewing scientists, Carson found two scientific camps when it came to pesticides: those who dismissed the possible danger of pesticide spraying barring conclusive proof, and those who were open to the possibility of harm and willing to consider alternative methods such as biological pest control.[40]

By 1959, the USDA's Agricultural Research Service responded to the criticism by Carson and others with a public service film, Fire Ants on Trial; Carson characterized it as "flagrant propaganda" that ignored the dangers that spraying pesticides (especially dieldrin and heptachlor) posed to humans and wildlife. That spring, Carson wrote a letter, published in The Washington Post, that attributed the recent decline in bird populations—in her words, the "silencing of birds"—to pesticide overuse.[41] That was also the year of the "Great Cranberry Scandal": the 1957, 1958, and 1959 crops of U.S. cranberries were found to contain high levels of the herbicide aminotriazole (which caused cancer in laboratory rats) and the sale of all cranberry products was halted. Carson attended the ensuing FDA hearings on revising pesticide regulations; she came away discouraged by the aggressive tactics of the chemical industry representatives, which included expert testimony that was firmly contradicted by the bulk of the scientific literature she had been studying. She also wondered about the possible "financial inducements behind certain pesticide programs."[42]

Research at the Library of Medicine of the National Institutes of Health brought Carson into contact with medical researchers investigating the gamut of cancer-causing chemicals. Of particular significance was the work of National Cancer Institute researcher and environmental cancer section founding director Wilhelm Hueper, who classified many pesticides as carcinogens. Carson and her research assistant Jeanne Davis, with the help of NIH librarian Dorothy Algire, found evidence to support the pesticide-cancer connection; to Carson the evidence for the toxicity of a wide array of synthetic pesticides was clear-cut, though such conclusions were very controversial beyond the small community of scientists studying pesticide carcinogenesis.[43]

By 1960, Carson had more than enough research material, and the writing was progressing rapidly. In addition to the thorough literature search, she had investigated hundreds of individual incidents of pesticide exposure and the human sickness and ecological damage that resulted. However, in January, a duodenal ulcer followed by several infections kept her bedridden for weeks, greatly delaying the completion of Silent Spring. As she was nearing full recovery in March (just as she was completing drafts of the two cancer chapters of her book), she discovered cysts in her left breast, one of which necessitated a mastectomy. Though her doctor described the procedure as precautionary and recommended no further treatment, by December Carson discovered that the tumor was in fact malignant and the cancer had metastasized.[44] Her research was also delayed by revision work for a new edition of The Sea Around Us, and by a collaborative photo essay with Erich Hartmann.[45] Most of the research and writing was done by the fall of 1960, except for the discussion of recent research on biological controls and investigations of a handful of new pesticides. However, further health troubles slowed the final revisions in 1961 and early 1962.[46]

It was difficult finding a title for the book; "Silent Spring" was initially suggested as a title for the chapter on birds. By August 1961, Carson finally agreed to the suggestion of her literary agent Marie Rodell: Silent Spring would be a metaphorical title for the entire book—suggesting a bleak future for the whole natural world—rather than a literal chapter title about the absence of birdsong.[47] With Carson's approval, editor Paul Brooks at Houghton Mifflin arranged for illustrations by Louis and Lois Darling, who also designed the cover. The final writing was the first chapter, A Fable for Tomorrow, which Carson intended as a gentle introduction to what might otherwise be a forbiddingly serious topic. By mid-1962, Brooks and Carson had largely finished the editing, and were laying the groundwork for promoting the book by sending the manuscript out to select individuals for final suggestions.

0 notes

Text

The Search for a New Humility: Václav Havel on Reclaiming Our Human Interconnectedness in a Globalized Yet Divided World

“Our respect for other people… can only grow from a humble respect for the cosmic order and from an awareness that we are a part of it… and that nothing of what we do is lost, but rather becomes part of the eternal memory of being.”

In his clever 1958 allegory I, Pencil, the libertarian writer Leonard Read used the complex chain of resources and competences involved in the production of a single pencil to illustrate the vital web of interdependencies — economic as well as ethical — undergirding humanity’s needs and knowledge. “We are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality,” Dr. King wrote from Birmingham City Jail five years later, as the material aspects of our interconnectedness became painfully inseparable from the moral. “Whatever affects one directly, affects all indirectly.”

How to inhabit our individual role in that mutuality with responsible integrity is what the great Czech dissident Václav Havel (October 5, 1936–December 18, 2011) addressed in his 1995 Harvard commencement address, later published under the title “Radical Renewal of Human Responsibility” in his collected speeches and writings, The Art of the Impossible: Politics as Morality in Practice (public library).

Václav Havel

Havel — a man of immense erudition and literary genius, who embodied Walt Whitman’s insistence that literature is essential for democracy, who went from playwright to president, who endured multiple imprisonments to uphold his ideals of justice, humanism, anti-consumerism, and environmental responsibility — begins by recounting an incident that sobered him to the irreversible forces of globalization: Sitting at a waterfront restaurant one evening, watching young people drink the same drinks as those served in his homeland to the sound of the same music that fills Prague’s cafés, surrounded by the same advertisements, he is reminded of the fact that he is in Singapore only by the different facial features of his fellow diners.

A decade before the social web subverted geography to common interests, values, and sensibilities as the centripetal force of community formation, Havel writes:

The world is now enmeshed in webs of telecommunication networks consisting of millions of tiny threads, or capillaries, that not only transmit information of all kinds at lightning speed, but also convey integrated models of social, political and economic behavior. They are conduits for legal norms, as well as for billions and billions of dollars crisscrossing the world while remaining invisible even to those who deal directly with them…. The capillaries that have so radically integrated this civilization also convey information about certain modes of human co-existence that have proven their worth, like democracy, respect for human rights, the rule of law, the laws of the marketplace. Such information flows around the world and, in varying degrees, takes root in different places.

And yet, with prescience painfully evident two decades later, Havel cautions that there is a dark side to this undamming of information and ideas:

Many of the great problems we face today, as far as I understand them, have their origin in the fact that this global civilization, though in evidence everywhere, is no more than a thin veneer over the sum total of human awareness… This civilization is immensely fresh, young, new, and fragile, and the human spirit has accepted it with dizzying alacrity, without itself changing in any essential way. Humanity has gradually, and in very diverse ways, shaped our habits of mind, our relationship to the world, our models of behavior and the values we accept and recognize. In essence, this new, single epidermis of world civilization merely covers or conceals the immense variety of cultures, of peoples, of religious worlds, of historical traditions and historically formed attitudes, all of which in a sense lie “beneath” it. At the same time, even as the veneer of world civilization expands, this “underside” of humanity, this hidden dimension of it, demands more and more clearly to be heard and to be granted a right to life.

And thus, while the world as a whole increasingly accepts the new habits of global civilization, another contradictory process is taking place: ancient traditions are reviving, different religions and cultures are awakening to new ways of being, seeking new room to exist, and struggling with growing fervor to realize what is unique to them and what makes them different from others. Ultimately they seek to give their individuality a political expression.

With an eye to the dangerously disproportionate dominance of Euro-American values in this global marketplace of values and ideas, Havel writes:

It is a challenge to this civilization to start understanding itself as a multicultural and a multipolar civilization, whose meaning lies not in undermining the individuality of different spheres of culture and civilization but in allowing them to be more completely themselves. This will only be possible, even conceivable, if we all accept a basic code of mutual coexistence, a kind of common minimum we can all share, one that will enable us to go on living side by side. Yet such a code won’t stand a chance if it is merely the product of a few who then proceed to force it on the rest. It must be an expression of the authentic will of everyone, growing out of the genuine spiritual roots hidden beneath the skin of our common, global civilization. If it is merely disseminated through the capillaries of the skin, the way Coca-Cola ads are – as a commodity offered by some to others – such a code can hardly be expected to take hold in any profound or universal way.

Illustration from Alice and Martin Provensen’s vintage adaptation of Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey

Acknowledging that such a line of thought might be dismissed by cynics as unrealistically utopian, Havel insists on not losing hope — lucid hope. “This is an extraordinary time full of vital, transformative movements that could not be foreseen,” Rebecca Solnit would write a generation later in her electrifying manifesto for civilizational resilience. “It’s also a nightmarish time. Full engagement requires the ability to perceive both.”

A decade before philosopher Jonathan Lear made his case for “radical hope,” Havel writes:

I have not lost hope because I am persuaded again and again that, lying dormant in the deepest roots of most, if not all, cultures there is an essential similarity, something that could be made if the will to do so existed – a genuinely unifying starting point for that new code of human co existence that would be firmly anchored in the great diversity of human traditions.

He points out that at the heart of every spiritual tradition, no matter its geographic or temporal origin, is a set of common moral principles upholding values like kindness, benevolence, and respect for human dignity. And yet, in an era of such irreversible triumphs of science as the splitting of the atom and the discovery of DNA — triumphs which Einstein believed united humanity through “the common language of science” — any real movement toward healing the ruptures of our natural interconnectedness lies not in reverting to ancient religions but in integrating the achievements of reason with the core values of the human spirit. Half a century after pioneering biologist and writer Rachel Carson invited us to step out of the human perspective, Havel writes:

Only a dreamer can believe that the solution lies in curtailing the progress of civilization in some way or other. The main task in the coming era is something else: a radical renewal of our sense of responsibility. Our conscience must catch up to our reason, otherwise we are lost.

It is my profound belief that there is only one way to achieve this: we must divest ourselves of our egotistical anthropocentrism, our habit of seeing ourselves as masters of the universe who can do whatever occurs to us. We must discover a new respect for what transcends us: for the universe, for the earth, for nature, for life, and for reality. Our respect for other people, for other nations and for other cultures, can only grow from a humble respect for the cosmic order and from an awareness that we are a part of it, that we share in it and that nothing of what we do is lost, but rather becomes part of the eternal memory of being, where it is judged.

Illustration by Soyeon Kim from Wild Ideas

Havel calls for “the search for a new humility” — a search that politicians have an especial responsibility to enact:

Even in the most democratic of conditions, politicians have immense influence, perhaps more than they themselves realize. This influence does not lie in their actual mandates, which in any case are considerably limited. It lies in something else: in the spontaneous impact their charisma has on the public.

In a passage of bittersweet poignancy against the contrast of our present political reality, Havel adds:

The main task of the present generation of politicians is not, I think, to ingratiate themselves with the public through the decisions they take or their smiles on television. It is not to go on winning elections and ensuring themselves a place in the sun till the end of their days. Their role is something quite different: to assume their share of responsibility for the long-range prospects of our world and thus to set an example for the public in whose sight they work. Their responsibility is to think ahead boldly, not to fear the disfavor of the crowd, to imbue their actions with a spiritual dimension (which of course is not the same thing as ostentatious attendance at religious services), to explain again and again both to the public and to their colleagues – that politics must do far more than reflect the interests of particular groups or lobbies. After all, politics is a matter of servicing the community, which means that it is morality in practice, and how better to serve the community and practice morality than by seeking in the midst of the global (and globally threatened) civilization their own global political responsibility: that is, their responsibility for the very survival of the human race?

Standing before “perhaps the most famous university in the most powerful country in the world,” Havel issues a particularly urgent exhortation to American politicians:

There is simply no escaping the responsibility you have as the most powerful country in the world.

There is far more at stake here than simply standing up to those who would like once again to divide the world into spheres of interest, or subjugate others who are different from them, and weaker. What is now at stake is saving the human race. In other words, it’s a question of what I’ve already talked about: of understanding modern civilization as a multicultural and multipolar civilization, of turning our attention to the original spiritual sources of human culture and above all, of our own culture, of drawing from these sources the strength for a courageous and magnanimous creation of a new order for the world.

With a cautionary eye to “the banal pride of the powerful” — corruption of character which Hannah Arendt followed to its gruesome extreme in her timeless treatise on the banality of evil — Havel adds:

Pride is precisely what will lead the world to hell. I am suggesting an alternative: humbly accepting our responsibility for the world.

Looking back at his own life with the astonishment of one who grew up under the locked-in nationalism of a communist authoritarian regime, then went on to travel to places like Singapore and address the graduating class at Harvard, Havel ends on a note of radical, responsible hope:

I have been given to understand how small this world is and how it torments itself with countless things it need not torment itself with if people could find within themselves a little more courage, a little more hope, a little more responsibility, a little more mutual understanding and love.

Complement this fragment of Havel’s wholly ennobling Art of the Impossible with other exceptional commencement addresses — including 21-year-old Hillary Rodham on making the impossible possible and Joseph Brodsky on our mightiest antidote to evil — then revisit Eleanor Roosevelt on the power of personal responsibility in social change.

donating = loving

Bringing you (ad-free) Brain Pickings takes me hundreds of hours each month. If you find any joy and stimulation here, please consider becoming a Supporting Member with a recurring monthly donation of your choosing, between a cup of tea and a good dinner.

newsletter

Brain Pickings has a free weekly newsletter. It comes out on Sundays and offers the week’s most unmissable reads. Here’s what to expect. Like? Sign up.

0 notes

Text

Hyperallergic: A History of Science Fiction’s Future Visions

Installation view of Into the Unknown at the Barbican in London (photo by the author for Hyperallergic)

LONDON — The 1982 film Blade Runner imagined 2019 Los Angeles as a dystopia of noirish neon and replicants, robots sent to do hard labor on off-world colonies. It’s a future in which engineered beings are so close to humans as to make the characters question the very nature of life. We’re now just a couple of years from this movie’s timeline, and although our robots are still far from mirroring humanity, our science fiction continues to envision giant leaps in technology that are often rooted in contemporary concerns of where our innovations are taking us.

Patrick Gyger, curator of Into the Unknown: A Journey through Science Fiction at the Barbican Centre, told Hyperallergic that, for him, science fiction “allows creators to look beyond the horizon of knowledge and play with concepts and situations.” The exhibition is a sprawling examination of the genre of science fiction going back to the 19th century, with over 800 works. These include film memorabilia, vintage books, original art, and even a kinetic sculpture in a lower-level space by Conrad Shawcross. “In Light of The Machine” has a huge, robotic arm twisting within a henge-like circle of perforated walls, so visitors can only glimpse its strange dance at first, before moving to the center and seeing that it holds one bright light at the end of its body.

Film still from 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) (courtesy the Roger Grant Archive)

Most of Into the Unknown is concentrated in the Barbican’s Curve space, a winding gallery with a high ceiling that permits objects to be stacked to the ceiling. They range from spacesuits worn in Star Trek and Moon (2009), to the robot TARS from Interstellar (2014) and Ava from Ex Machina (2015), to drawings by H. R. Giger for the Alien series and paintings by James Gurney for his Dinotopia books. The post-war architecture of the Barbican is a fitting setting for Into the Unknown, with its concrete angles and utopian spirit. In conjunction with the show, Penguin Classics released a series of limited-edition science fiction books with Barbican architecture on their covers. The brutalist conservatory graces H. G. Well’s The Island of Doctor Moreau, and two of the triangular towers appear on George Orwell’s 1984.

Throughout the exhibition, niche and popular culture are juxtaposed, chronicling how science fiction emerged as a cultural force in the 20th century. Manuscripts by Jules Vernes hold incredible insights into how much research the author put into works such as Around the World in Eighty Days (1872), and an adjacent display of dinosaur models sculpted by Ray Harryhausen for 1960s stop-motion shows how, by the mid-20th century, films were using recent scientific knowledge for entertainment. Artwork like Dino De Laurentiis’s storyboard drawings for the Sandworm battle in the 1984 Dune (and some nearby concept art by Giger for Alejandro Jodorowsky’s unrealized version), testify to artists’ presence in shaping science fiction. An array of aerospace industry advertisements from the 1950s and ’60s feature fantastic space crafts similar to those in Soviet postcards illustrated by Andrey Sokolov and Aleksey Leonov (a cosmonaut who created the first artwork in space).

youtube

Gyger noted that the fact that the genre “has been so impactful” cannot be separated from the link to “its context of production and to the mass market that makes it flourish.” Over the years, this has involved pulp magazines, trading cards, comics, and paperbacks, often aimed at young audiences, or presented as a cheap thrills.

Certainly science fiction is incredibly popular at the moment — see the success of Westworld, The Handmaid’s Tale, and Black Mirror (which is featured in the exhibition through a six-foot video installation based on the unnerving virtual world in the episode “Fifteen Million Merits“). While these series explore serious issues in our reality, there’s still a tendency to overlook them as serious art (unless you count The Lord of the Rings, no science fiction film has won the “Best Picture” Oscar, for instance). Into the Unknown might not sway anyone without a curiosity for science fiction, being that you’re immediately immersed in a constellation of spaceships, dinosaurs, alien monsters, and robots. But for those with an interest, it demonstrates how these themes developed from “low to “high” art.

Postcard of “On the first Lunar cosmodrome” (1968), by Andrey Sokolov and Aleksey Leonov (courtesy Moscow Design Museum)

Andrey Sokolov and Aleksey Leonov, postcard series from the set “A man in space” (1965), offset printing on paper, full-color (photo by the author for Hyperallergic)

The exhibition shows, but does not dwell on, who has been left out of a history mostly shaped by white men (there are rare exceptions on view, like the “Astro Black” video installation by Soda_Jerk that muses on Sun Ra’s theories of Afrofuturism). It would be worthwhile to spend more time on figures who broke through these barriers, such as author Octavia Butler. As discussed on a recent podcast from Imaginary Worlds, her black characters were sometimes portrayed as white on her book covers to make them more appealing to science fiction readers. The exhibition could also have a deeper context for why certain veins of science fiction are prominent in particular eras, and perhaps question why we don’t have a lot of science fiction narratives on current crises like climate change. For instance, the much smaller 2016 exhibition Fantastic Worlds: Science and Fiction 1780–1910 from the Smithsonian Libraries compared milestones like Mary Shelley’s 1818 Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus with physician Luigi Galvani’s “animal electricity” experiments on animating dead frog legs, and highlighted how Jules Verne channeled the doomed Franklin expedition in his 1864 book The Adventures of Captain Hatteras.

Nevertheless, having an exhibition like Into the Unknown at a mainstream space like the Barbican is significant, showing the art world appreciates science fiction beyond kitsch. And science fiction continues to be one of our important portals for thinking about the ramifications of our technological choices, and where they might take us. There’s a reason that 1984 is now having a popular Broadway production in a year of “alternative facts,” and why Black Mirror episodes such as “Nosedive,” where a person’s worth is judged by their social media “likes,” resonate so deeply.

“It is the genre of ‘what if,’ shedding light on our hopes and fears for a future closely linked to our present and our environment,” Gyger said. “In doing so it inspires and warns us, while entertaining us, creating a plethora of iconography, and leaving a deep mark on culture.”

Dinosaurs designed for films in the 1950s and ’60s by Ray Harryhausen (photo by the author for Hyperallergic)

Installation view of Into the Unknown at the Barbican in London (photo by the author for Hyperallergic)

Glass plates for magic lantern depicting scenes from Jules Verne’s Around the World in Eighty Days (Paris,

1885), lithographic transfer on glass (photo by the author for Hyperallergic)

Albert Badoureau, “Le Titan Moderne: Notes et observations remises à Jules Verne pour la rédaction de son roman sans dessus dessous” (“The Modern Titan: Notes and observations presented to Jules Verne for the writing of his novel The Purchase of the North Pole or Topsy-Turvy,” 1888), manuscript page (photo by the author for Hyperallergic)

“L’an 2000” (“The year 2000,” 1901), print on cardboard; a collection of uncut sheets for confectionery cards showing life imagined in the future (photo by the author for Hyperallergic)

Amazing Stories #1 (July 1933), Agence Martienne (courtesy Maison d’Ailleurs/Agence Martienne)

8mm film reel boxes (1949–67) (photo by the author for Hyperallergic)

George Pal Productions, Luna spaceship miniature from the film Destination Moon (1950), mixed media (photo by the author for Hyperallergic)

Installation view of Into the Unknown at the Barbican in London (photo by the author for Hyperallergic)

Martian models by Ray Harryhausen for War of the Worlds (1949) and First Men in the Moon (1964) (photo by the author for Hyperallergic)

Anubis and Horus helmets by Patrick Tatopoulos for Stargate (1994), fiberglass with metallic surface (photo by the author for Hyperallergic)

Art by H. R. Giger for Alien III (1992) (photo by the author for Hyperallergic)

The Original Science Fiction Stories #1 (November 1958), Agence Martienne (courtesy Maison d’Ailleurs/Agence Martienne)

Dino De Laurentiis, series of three Sandworm battle storyboards for the film Dune (1984), pencil on vellum adhered to board (photo by the author for Hyperallergic)

Magazine cover, Amazing Stories #1 (April 1926), Agence Martienne (courtesy Maison d’Ailleurs/Agence Martienne)

Theta space station miniature from the TV series Buck Rogers in the 25th Century(1979–81); Kane (John Hurt) space suit from the film Alien (1979) (photo by the author for Hyperallergic)

Trevor Paglen, “Orbital Reflector (Diamond Variation)” (2017), freestanding model for inflatable spacecraft; aluminum, stainless steel, acrylic (photo by the author for Hyperallergic)

Conrad Shawcross,” In Light of The Machine,” kinetic installation (photo by the author for Hyperallergic)

Into the Unknown: A Journey through Science Fiction continues through September 1 at the Barbican Centre (Silk Street, London, UK).

The post A History of Science Fiction’s Future Visions appeared first on Hyperallergic.

from Hyperallergic http://ift.tt/2we9DQ6

via IFTTT

0 notes

Text

A boy covered in young opossums

By: Charles Philip Fox

From: The Illustrated Library of the Natural Sciences

1958

#captivity#virginia opossum#opossum#marsupial#mammal#1958#1950s#Charles Philip Fox#The Illustrated Library of the Natural Sciences

5K notes

·

View notes

Text

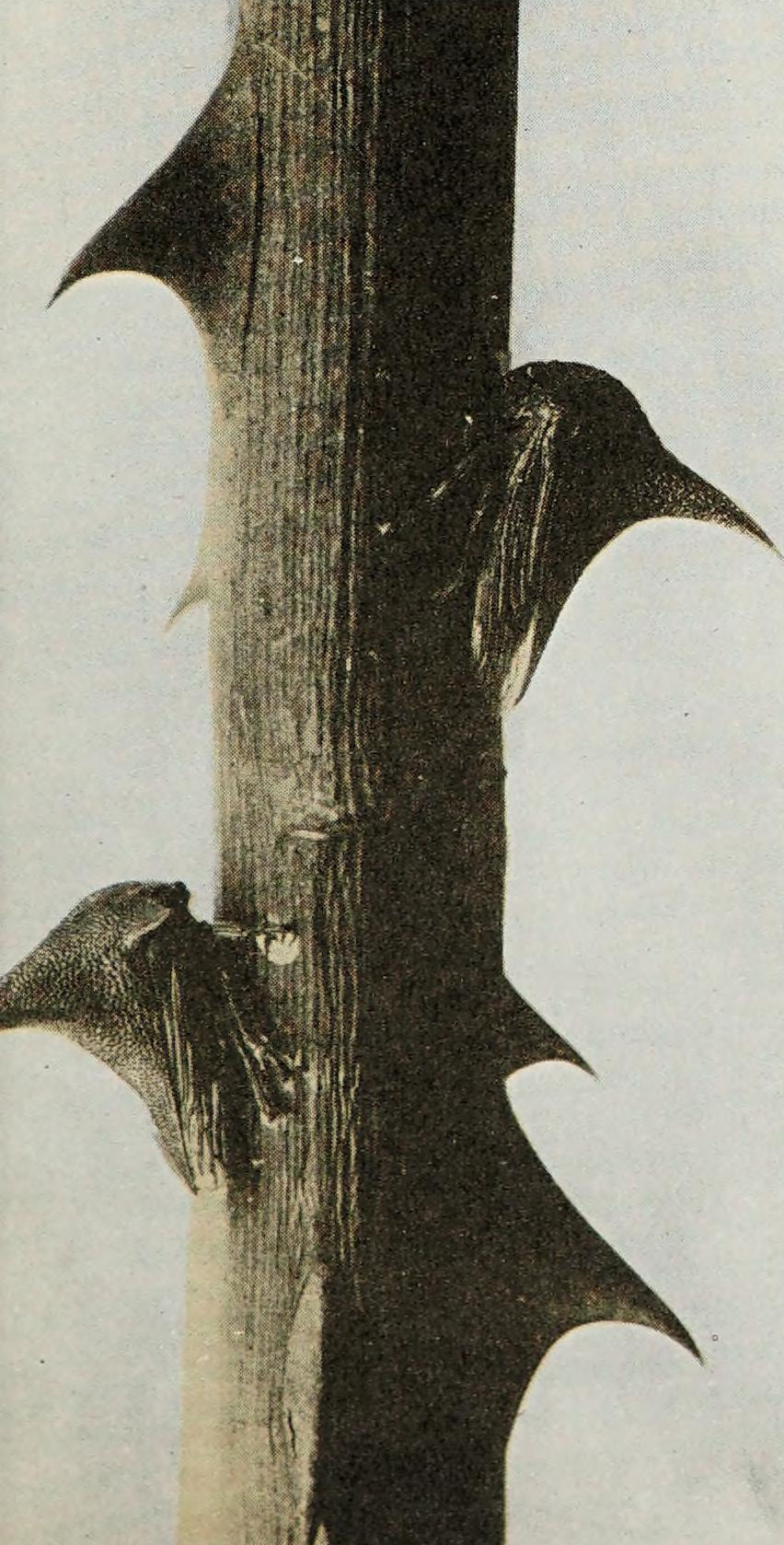

Thorn bugs hiding on a thorny stem

By: Leonhardt / Black Star

From: The Illustrated Library of the Natural Sciences

1958

#thorn bug#true bug#insect#arthropod#invertebrate#1958#1950s#Leonhardt#The Illustrated Library of the Natural Sciences

869 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hornet posed on a bullet

By: AMNH

From: The Illustrated Library of the Natural Sciences

1958

#wasp#hymenopteran#insect#arthropod#invertebrate#1958#1950s#AMNH#The Illustrated Library of the Natural Sciences (1958)

278 notes

·

View notes

Text

A man holding a North American river otter, which is gently biting his nose

By: E. P. Walker

From: The Illustrated Library of the Natural Sciences

1958

#captivity#north american river otter#otter#mustelid#carnivore#mammal#1958#1950s#E. P. Walker#The Illustrated Library of the Natural Sciences (1958)

239 notes

·

View notes

Text

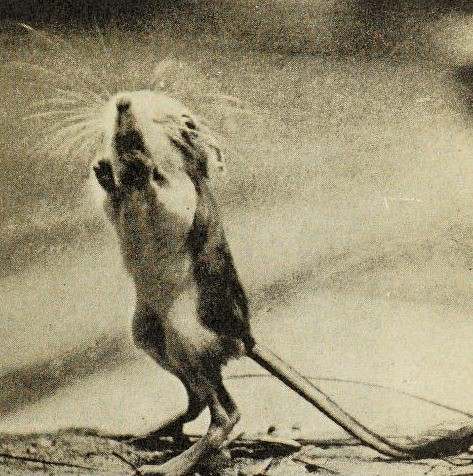

Kangaroo rat

By: Vernon Bailey

From: The Illustrated Library of the Natural Sciences

1958

#kangaroo rat#castorimorph#rodent#mammal#1958#1950s#Vernon Bailey#The Illustrated Library of the Natural Sciences (1958)

287 notes

·

View notes

Text

Virginia opossum

By: Charles Philip Fox

From: The Illustrated Library of the Natural Sciences

1958

#captivity#virginia opossum#opossum#marsupial#mammal#1958#1950s#Charles Philip Fox#The Illustrated Library of the Natural Sciences

182 notes

·

View notes