#Old Admiralty Building

Text

Simeon Saves Westminster

Dear Simeon,Enemy agency REEL (Really Evil Espionage League) are on the attack in London. Our intelligence sources have revealed a wicked plan to set off supersonic whistles using tiny electronic amplification devices planted in the secret tunnels under Horse Guards Parade. The devices play a version of the Baby Shark song, which is inaudible to human ears but has been found to drive horses in…

View On WordPress

#Ada Lovelace#Admiralty Arch#Alan Brooke#Baby Shark#Bali memorial#Captain James Cook#cenotaph#Chatham House#Clarence House#Earl Haig#green park#John Franklin#John Peake Knight#ko-fi#Monument to the women of world war ii#Old Admiralty Building#patreon#Pickering Place#Queen Anne&039;s Gate#Robert Falcon Scott#Simeon#spy trail#St James&039;s Park#St James&039;s Square#St James&039;s Theatre#the adventures of Simeon#The Mall#theadventuresofsimeon#Treasure Trails#westminster

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Admiralty

I often mention the Admiralty, as some sort of vague governing body, but i think have not explain what it is and what it does. Well the term is used to describe the goverment department which was once responsible for Britain's naval affairs. In fact, until the union of Scotland and England in 1707 it was the English Admiralty, and the Scots had their own version. The term is - or was- used by other countries, and of course it had its equivalents to the US Department of the Navy, which is now part of the Department of Defense. The French equivalent was the Ministère de la Marine, but it is now run as part of the centralized Department of Defence. Today, Britain's naval affairs are administered by the Ministry of Defence.

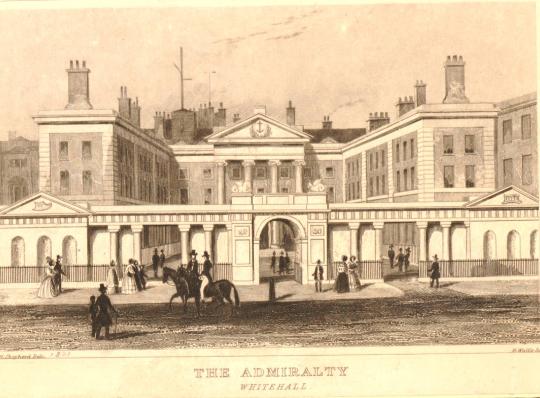

The Admiralty in Whitehall, London

The origins of the Admiralty date back to the late 13th century and the reign of King Edward I (reign 1272-1307). He appointed a Lord High Admiral as the head of his small navy, and gave him a suite of offices in London. These offices became known as the Lords Commissioners of the Admiralty, and when they met for their regular meetings they were known collectively as the Board of Admiralty. The Sea Lords were senior serving officers, who tended to handle operational matters, while the Lords of the Admiralty were civil servants or politicans who dealt more with administration and governance. This system continued in use for almost 7 centuries until the Admiralty was disbanded in 1964. From then on all three of Britain's Armed services were administered by the Ministry of Defence. The Admiralty building stands in London's Whitehall and in the time of the 18th and 19th century and aspecially in wartime its offices were a bustling hive of activity, with officers arrving in the hope for a ship, or to be court- martialled, or to receive their orders. Admirals, civil servants and politicians went about their business, holdings meetings, making judgements ans sending or receiving a welter of reports.

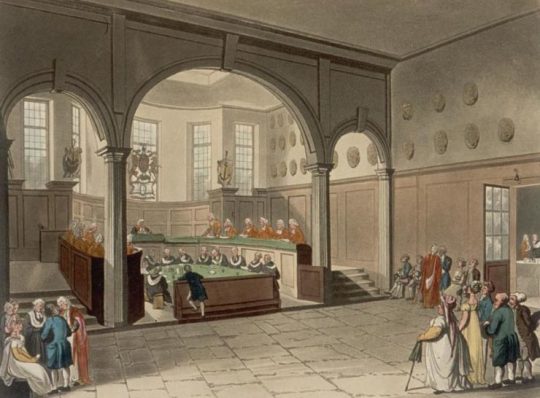

But the Admiralty was more then just a place where the Royal Navy was administered. There were also the Admiralty Courts, where piracy and other naval cases were heard, but the High Court of Admiralty was the highest and heard all British maritime cases and the Prizes (where it was determined whether a ship was a legal prize or not and how much prize money came out) until it was dissolved in 1875.

The High Court of Admiralty

The Navy Board (formerly known as the Council of the Marine or Council of the Marine Causes) was the commission responsible for the day-to-day civil administration of the Royal Navy between 1546 and 1832.

As the size of the fleet grew, the Admiralty sought to focus the activity of the Navy Board on two areas: ships and their maintenance, and naval expenditure. Therefore, from the mid- to late-17th century, a number of subsidiary Boards were established to oversee other aspects of the board's work. These included:The Victualling Board (1683–1832). Responsible for providing naval personnel with food, drink and supplies. The Sick and Hurt Board (established temporarily in times of war from 1653, placed on a permanent footing from 1715, amalgamated into the Transport Board from 1806). Responsible for providing medical support services to the navy and managing prisoners of war. The Transport Board (1690–1724, re-established 1794, amalgamated into the Victualling Board in 1817). Responsible for the provision of transport services and for the transportation of supplies and military equipment.

Each of these subsidiary Boards went on to gain a degree of independence (though they remained, nominally at least, overseen by the Navy Board.

So you see it was more than just a place where old admirals met for brandy, it was the heart of the navy and its administrative headquarters.

#naval history#the admiralty#administration#royal navy#13th -20th century#medieval seafaring#age of discovery#age of sail#age of steam

107 notes

·

View notes

Text

Pin Mill on the River Orwell in Suffolk

Pin Mill is a popular destination for sailors, walkers, artists, photographers and those visiting the centuries old Butt and Oyster public house.

The Butt and Oyster was first recorded as a public house in 1553 when licensing laws began. The Port of Ipswich’s bailiffs and burgesses held Admiralty Courts there between 1546 and 1552.

Pin Mill was in the past a landing point for cargo heading in and out of Suffolk.

Up to the Second World War huge sailing ships, which brought grain from around the world, would anchor at Butterman’s Bay, close to Pin Mill, to offload cargo onto barges so that the ships were lightened to enter the dock at Ipswich. Boat building and repairs still continue at Pin Mill today. There are now several house boats moored along the bank towards Shotley.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

The maverick heroics of MI6 agent James Bond may actually be based on the true story of one brave soldier, who took on the Germans and won again and again. In this archive piece, we look back on Patrick Dalzel-Job's stranger-than-fiction life

If the dashing hero of Ian Fleming's best-selling spy thrillers were among us, is it likely he could be found living alone on a far-away hill by the sea in Scotland?

A mildly spoken gentleman who lived to his eighties, then grey and a little stooped—could he have been secret agent 007? Come on.

Ah, but life is stranger than fiction.

Some of those who know best have always believed that Fleming based his superspy on a wartime comrade named Patrick Dalzel-Job—yes, our elderly gentleman who lived his final days in the Highlands.

There were other influences, of course. Bond's love of vodka martinis and handmade cigarettes came, in fact, from Ian Fleming himself; and whereas 007 tumbled into bed with a different beauty every few pages, Patrick Dalzel-Job (pronounced Deal-Jobe), loved only one woman all his life.

But there is something here. Consider:

Job, like Bond, was half Scots, a one-time naval officer, a master of languages who in real life performed precisely the kinds of derring-do Fleming later attributed to his flamboyant make-believe hero.

By the time Dalzel-Job walked into Commander Ian Fleming's Admiralty office one day in 1944 looking for a new assignment, he had already seen service as a seaman, commando, submariner and spy, and had just become probably the first naval officer to qualify for army parachute wings.

Fleming, an ex-journalist who had broadcast his intention of becoming a best-selling author some day, was then building up the clandestine army of naval intelligence officers and Royal Marine commandos which was to move out in front of the assault troops on D-Day and capture secret enemy documents and weapons.

He saw in Patrick's flinty blue eyes the look of a man whose mettle has been tested, and promptly signed him on.

Says veteran BBC broadcaster Charles Wheeler, who served with both: "Who could be surprised if a kind of James Bond seed were planted then and there?"

An unconventional childhood

Patrick Dalzel-Job, born in Twickenham, Middlesex, in 1913, was three years old when his father, an infantry officer, was killed in France. His mother, a small, spirited woman, brought him up alone.

They lived on the Sussex coast, then moved to Berkhamsted in Hertfordshire, where Patrick went to school. But he was a sickly boy, inept at team sports and home with mysterious bouts of fever more often than he was in class.

When he was 14, his mother took him to Switzerland, where the mountain air restored his health and he became an expert skier. He continued to read widely in French and English, but his formal education was over.

Drawn to Norway by stories he'd read as a boy, in 1937—the summer of his twenty-fourth birthday—he set sail from Scotland in a 37-foot schooner, Mary Fortune, whose deck work and interior he had built himself.

With his mother as crew, he spent the next two years exploring a wilderness of fiords and islands from Bergen in the south-west to Nordkapp, on the northernmost coast of Europe.

His mother knew nothing of seamanship, but an ingenious array of ropes, chains and pulleys enabled Patrick to man the rugged little schooner single-handed.

Soon he was speaking Norwegian like a native and making friends up and down the western coast. A deep-rooted love for Norway and its people became a cornerstone of his life.

Falling in love with Norway

Wherever he sailed through the complex of waterways, he drew detailed charts, convinced they would be of use to the Royal Navy if war came. But when he sent them to the Admiralty, they were accepted with indifference.

And three years later, when the Germans invaded Norway and coastal charts of any kind were desperately needed, his could not be found.

Meanwhile Patrick, preparing the Mary Fortune for a voyage north to the Arctic Ocean, decided he needed another hand on board and turned to friends in Tromso, the Bangsunds: might one of their children be interested?

The keenest was 13-year-old Bjørg, with her wide blue eyes and a laugh that was the most beautiful sound Patrick had ever heard.

All through that spring and summer, Bjørg was a valiant and valuable shipmate, cheerfully helping out in the galley and learning how to handle the tiller. Then, in early September, their radio brought news that the war had come.

Mary Fortune headed back to Tromso, where all the Bangsunds came to see off Patrick and his mother, their possessions reduced to what they could carry in two suitcases, on the coastal steamer.

As the ship ploughed through the night towards Britain, Patrick found a scrap of paper from Bjørg under his pillow. "I love you," it said.

The nazis and the Norwegians

In April 1940 Patrick, now an officer in the Royal Navy, was again bound for his beloved Norway.

The Nazis, in a brutal move to assure command of the northern sea lanes, had invaded their neutral neighbour, and an Allied expeditionary force was steaming north in an attempt to dislodge them.

Patrick was assigned the task of disembarking the troops at Harstad, 150 miles north of the Arctic Circle, and conveying them to combat staging areas.

This he did by organising fisherman friends, and their friends, into a flotilla of more than 100 of their boats. The objective was nearby Narvik, an ice-free port seized by the Germans as a base from which to protect their supply of vital iron ore from neutral Sweden.

The Norwegians did as Patrick said because they trusted him and he spoke their language; also because he never hesitated to fire a round from his father's old service revolver across their bows when they forgot this was war and not just another fishing trip.

Wearing an unmarked greatcoat over his sub-lieutenant's insignia and barking orders as if born to command, he even had senior officers calling him "Sir".

The Allies captured Narvik—but held it only briefly. They were too few and had come too late. By the end of May, all but a small force had been withdrawn. No one doubted that Luftwaffe bombers would soon be rumbling across the sky, aiming to drive off the rest.

A daring rescue

On May 29 Patrick, standing offshore of the town with his ragtag fishing fleet, learned to his horror that no provision had been made to evacuate the townspeople.

His urgent enquiries only prompted a stern message from force headquarters: he was to hold his boats in reserve and not—"repeat not"—concern himself with the civilian population.

At midnight, a crisis meeting of the city council was still agonising about how they could evacuate the people to the designated safe areas. The then mayor, Theodor Broch, tells what happened next:

"There was a commotion by the door. A young Englishman said he had to talk to me, that we had to evacuate the town. I barked at him that we had no boats."

"I have the boats," said Patrick. "Let's go."

His providential appearance in defiance of strict orders; that clipped self-assurance; rescuing the population of a doomed city—what could have been more James Bondian?

Within the hour, under Patrick's close supervision, women and children were being handed down into the boats.

"I have never forgotten him," says Gerd Carlsson, who was 21 and boarding with her sister and baby nephew. "There was shooting from land and sea, and lines of waiting people, and such a babble of shouting. But he shook each person's hand warmly and was so calm that although I didn't even know where I was going, I wasn't afraid."

During the next two days and nights, 4,500 people were ferried to safety in dozens of communities along the surrounding waterways.

Early on June 2, Patrick and Mayor Broch walked together through Narvik's empty streets, making sure no one was left behind. By then, even the last of the troops had slipped away.

But hours later, while Patrick was still there, the bombers came, turning the town's neat wooden buildings into an inferno, reducing most of them to splinters and ashes.

Patrick watched as Narvik burned, heartsick because he knew there was nothing in the town of military value, only people's homes.

Wartime intelligence

On June 8, Patrick went back to Britain, disillusioned by the Allied defeat, bitter that he hadn't managed to stay behind and organise a Norwegian resistance—and dreading a message from the Admiralty that he was to be court-martialled for gross disobedience of orders at Narvik.

Instead, the Admiralty signalled him with a message from King Haakon VII of Norway: His Majesty would be in London shortly and he would personally present Lieutenant Dalzel-Job with the Knight's Cross of St Olav, Norway's highest order, for saving the people of Narvik.

After that, nothing was heard about a court-martial. But Patrick was relegated to a series of converted merchantmen that zigzagged across the South Atlantic intercepting blockade-breakers or convoying Allied freighters safely to port.

"All this", he recalled in the book he later wrote (and published) about his adventures, "seemed terribly monotonous to me."

Just as he began thinking the war had passed him by, Lord Louis Mountbatten summoned him to London and put him in charge of motor torpedo boat (MTB) operations in Norway. It was particularly dangerous work, for the Germans were throwing all they had into defending Norway's coast.

But Patrick knew plenty of narrow entrance channels that the Germans didn't. His MTBs raised havoc with commando raids, sabotage and attacks on enemy ships.

It forced the Germans to step up defensive operations and induced trepidation quite out of proportion to the number of MTBs employed against them.

Still only a lieutenant, Patrick was next posted to a detachment of midget submarines. In September 1943, he briefed their four-man crews on the remote Arctic estuary where the German battleship Tirpitz was moored in apparent safety; three of the tiny craft crept into the fiord and crippled her in a raid that earned VCs for two of the participants.

Next, equipped with a radio transmitter, he was put ashore on a Norwegian island, on a one-man intelligence mission to track supply convoy patterns through the inland waters.

He knew that capture meant summary execution, on Hitler's own orders. Yet he remembers those three weeks, alone and utterly dependent on his own wit for survival, as among the most exhilarating of his life.

Taken off the island by pre-arrangement, he assuaged his reluctance to leave by directing the MTB that picked him up to a German merchantman whose anchorage he had noted. Two torpedoes finished her off.

James Bond rises through the ranks

On June 10, D-Day-plus-4, Patrick landed on Utah beach in Normandy as a member of Commander Ian Fleming's intelligence hit squad, the 30th Assault Unit (30 AU)—a name intended to mislead, since it was never meant to assault anything and probably took its number from an office door in the Admiralty.

Patrick, promoted to lieutenant-commander, was in command of Team 4, reporting by courier directly to Fleming.

All the way through Normandy, Belgium and into Germany, Team 4 operated ahead of the assault troops in enemy-held territory, getting their hands on German documents, weapons and installations before they could be destroyed by the Germans or by Allied artillery.

Patrick revelled in it; this kind of war, where he was free to set the level of risk, was the kind he wanted to fight. And he sent back a steady stream of data and captured equipment.

He found the control centre for the long-range bombing of Allied convoys in the Atlantic; he recovered intact a new and dangerously effective midget submarine; reaching Cologne 24 hours before any other Allied troops, Team 4 walked unhindered into the vast Schmidding metalworks and took it over.

Patrick's audacity was sometimes breathtaking. When some nuns showed him a heavy safe used by the Germans, he promptly blew it open, breaking every window in the convent. He gave the money in the safe to the nuns for repairs and sent the documents in it to London.

His reports from the field to the desk-bound Ian Fleming kept fleshing out a portrait of the kind of man the would-be writer was conjuring up for his fictional hero. But Patrick's most stunning exploit was still to come.

An impossible stunt

The target was the vast Deschimag shipyard in Bremen where, he had heard from prisoners, there could be as many as 20 of the newest high-speed German submarines—a prize of enormous intelligence value.

But winning it would be a race: the 52nd Lowland Division, following on close behind 30 AU, was planning on blasting the shipyard into oblivion.

In the afternoon of April 26, 1945, Team 4 entered Bremen's deserted central square. A fretful policeman appeared. Please, he said to Patrick in the lead Jeep, would the commander accompany him to the city hall where the mayor was waiting?

Patrick found the mayor, dressed in formal black, alone in the empty, echoing chamber.

"He wanted me to accept the surrender of the city of Bremen and all its services," Patrick recalled, "and he gave me assurances of vigorous police action against any who failed to co-operate fully."

Patrick went at once to radio Army Command that organised military resistance was ended and whatever the Allies wanted would be done. "I told them that, except for some sniping, the city was secure. They didn't have to shell the shipyard."

But the Army did not see it that way. They were going to open fire that very evening, they replied, as soon as they came within range.

Furious, Patrick climbed into his scout car and set out alone for the shipyard, staking his life that there really was no resistance there, and that his presence would keep the Army from shelling it.

Then, at the very gates of the shipyard, his scout car sputtered and died—it had run out of petrol. And when he tried to radio for help, all he got was static; contact had been cut by interference from surrounding buildings.

It's like a bad film, Patrick remembers thinking. But what would happen in the last reel?

He considered going ahead on foot, but needed the rest of his team with the radio truck. Without it, how could he tell the Army he was inside the shipyard? He would only get killed there.

Spotting some workers, he grabbed a bicycle from one of them. Frantically he pedalled back through the sunset to his unit—aware that there was still enough daylight for a sniper to put a bullet in his back.

When he rounded the last corner, his anxiously waiting men hauled him on board the lead vehicle, bicycle and all, and the column sped off for the shipyard at breakneck speed.

Inside, they found 16 brand new submarines and two destroyers, and forestalled their imminent demolition by the shipyard technicians and directors.

Patrick and his men took them all prisoner, and in a night-long search found technical papers detailing the most recent German naval research, as well as machine tools of highly advanced design.

They had not heard the last from the Army. Early next morning, when submarine experts had already begun a detailed study of the captured U-boats, all of the new high-speed Type 21, a British Army staff officer appeared and asked Patrick to sign a receipt for them—implying that the 52nd Division had captured them.

This was the last straw for Patrick. He slammed the gate and had a sign posted on it to the effect that the entire shipyard was the property of 30 AU: "Keep Out!"

Bond gets the girl

The war ended soon after. Patrick never saw Ian Fleming again, nor did the British government reward his wartime valour with even a single honour or citation.

Among those who still wonder why is Rear Admiral Jan Aylen, then a Commander in 30 AU, who calls Patrick "one of the most enterprising, plucky and resourceful people that the Second World War produced".

The reason is not complicated. Frequently Patrick committed the unforgivable offence of disagreeing with senior officers and, worse, being proved right.

Just like James Bond.

As soon as the fighting ended, Patrick responded to the great hunger in his heart and returned to Norway.

Six years had passed; Bjørg was 19 now, a different person. He was different. But as soon as they saw each other, they knew they had only been marking time. They married three weeks later.

The James Bond years, about to begin for Ian Fleming, were over for Patrick. He and Bjørg went to Canada, where Patrick served in the Canadian navy and their son lain grew up.

In 1960 they settled near Plockton in the West Highlands, prepared to continue living happily ever after. Patrick taught in the village school and Bjørg became a pillar of the community until her death, in 1986, of cancer.

Patrick, brave as ever, soldiered on alone. He finally passed away in 2003.

Daily inspiration. Discover more photos at Just for Books…?

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

The splendor, the beauty of it! The Old Capital, in all its glory! That ancient star, old and orange, the storied history of all its worlds! Three thousand million people live across the many crowned worlds, considering themselves a maintenance crew until the return of true empire to the shores of the Thronestar. It has been so very long, after all.

The Regency Council of the Galactic Dominate (fourth iteration, one hundred eleventh dynasty, twenty-fifth council) governs this system in its entirety, making it one of a few systems officially under the ultimate control of a single polity. As the Galactic Dominate shrunk calamitously towards its current extent, its military took up the charge of local leadership- and as the final representative of that vast empire, the Thronestar's worlds exhibit the most advanced form of that hierarchy, so differently-labeled than the nobility in other parts of the galaxy. The Thronestar's worlds, save of course the Old Capital itself, each serve as the seat of an ancient Admiralty-General: all nominally descendants of the Last Admiral and Last Imperatrix of the Galactic Dominate. In theory, they divide the whole territory of the Galactic Dominate between themselves... in practice, each only has a certain hold over their local continent.

The rest of the planet and its environs will often consider themselves part of their domain until a dictate that they disagree with is handed down, generally resulting in either a quick and clean coup or the granting of "autonomy" to each piece beneath the Admiralty-General. The chain of command travels equally down the fleet side and the surface side, with defensive fleets controlled by Commodores and continents controlled by Commodores-General, all the way down to the lowest landed rank- Ensigns. Ultimately, of course, very little of this rule is abided by or even recognized- much like the rest of the galaxy, nobles are rulers in name only. The Regency Council gets off easier than most Empresses....

The Thronestar itself glows a ruddy orange, late-K and just as ancient as one might expect it to be. Its nearest companion is a vast gas giant, itself glowing, with a retinue of co-orbital asteroids. Beyond it is a series of terrestrial worlds, varied in shape and size- a runaway greenhouse, a blasted metallic world, a world strewn with cold rivulets of water, an ice-covered ball, and the rocks of the outer belt and cloud... and between them all, the Old Capital. It is one of a few worlds that can be said to have been truly habitiformed- tuned to look idyllic to its inhabitants. Its shallow turquoise oceans are floored by a vast mat of jelly reef, providing an astoundingly diverse ecosystem for what is usually a seafloor desert. Savannah plains lay in the wide gulfs between forest-covered mountain ranges, the axial tilt precisely controlled to provide only the most aesthetic seasons... and on one of the island continents, the One True Palace of the Empresses of the Galactic Dominate still stands. It is a *ridiculous* structure, even compared to the other Palaces worthy of the capitalization across the galaxy. In total it covers the entirety of the island continent on which it sits, wildlife preserves and parks and fountain-regions and annex buildings and dormitories and the several vast buildings of the Palace core.

Until the Galactic Dominate selects a new Empress, no one is allowed inside- at least, in theory. Who knows what has become of the maintenance drones, after millennia alone....

#Ramblings?#i'm weirdly proud of this one so: here it goes!#long post#i like hilariously nonfunctional space governments#and i also like fractal bullshit

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

On June 21st 1791 Robert Napier, regarded as the "father of Clyde shipbuilding" was born in Dumbarton.

Napier worked as an apprentice to his father before moving to Edinburgh where he worked for engineer Robert Stevenson.

In 1815, he began his own engineering business in Glasgow. Acknowledging Henry Bell's work in the development of the steam-powered Comet, Napier began building marine steam engines. His first engine performed well in the steamer Leven and is preserved today at the Denny Ship Model Experiment Tank. He founded Parkhead Forge in Glasgow in 1837 to make iron for boiler plate. In 1841, he began building ships, which included some of the earliest iron-clad warships. Napier did much to establish the international reputation of the River Clyde as an centre for ship-building. With the Canadian shipping tycoon Samuel Cunard, he planned steam-powered vessels for transatlantic service and helped set up a company to run them. Napier also proved the economy and versatility of steam-powered vessels to the Admiralty.

In 1849 he built Leviathan, the world's first train ferry, which sailed from Granton to Burntisland. The Persia, launched in 1854, was the world's largest ship and the ironclad Black Prince, which was launched from the navy at Govan in 1861, was the largest Clyde-built ship of its time.

Napier won international respect; he became President of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers and was honoured by France and Denmark. He made his home at West Shandon, by the Gare Loch, which he filled with a remarkable collection of furniture, porcelain and paintings, including old masters and works by 19th C. artists such as Raeburn and McCulloch.

Napier's wife died in 1875 and, overtaken by grief, he took ill and died at West Shandon the following year. Thousands lined the route to Dumbarton Parish Church, where he was buried in the family vault.

There is loads more about Napier here, including a lists of the ships he was involved in building over a period stretching 53 years http://www.gracesguide.co.uk/Robert_Napier

10 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Oriel Windows, Stepped-Gables and Famous Old Harrovians:

Speaking of its Oriel windows, terraced gardens and iconic stepped-gables, Famous Old Harrovian, Sir Winston Churchill, described it as the most beautiful building he had ever seen.

Interestingly though, it wasn't Old Schools at Harrow he was describing, but Chartwell, the house near Westerham in Kent, which became his home for more than forty years and was the base from which he waged war against Chamberlain's policy of appeasement to Nazi Germany during the years leading up to the Second World War.

The origins of the estate reach back to the fourteenth century, when it was known as Well Street. It was bought in 1848, by John Campbell Colquhoun, whose grandson it was who sold it to Churchill. But it wasn't Churchill who had those Oriel windows and stepped-gables added - it was Colquhoun.

So which school did Colquhoun attend? Yes, you got it, it was Harrow, where Colquhoun and Churchill had been friends!

Incidentally, though Chartwell was Churchill's long-term and much-loved home, he had numerous official residences during his political career, including: Admiralty House; 10 Downing Street; Chequers; and the Admiralty Yacht, HMS Enchantress!

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sunday 12th February 2023

Happy 4th Birthday to Elsie

The weather in this part of the world is very odd and has been so for some while. The sun is beating down again and temperatures have soared. The meteorologists are keeping a very close eye on Cyclone Gabrielle which is sweeping down from the top end out to the east and should miss the mainland but could cause strong winds on the way. Poor old NZ appears to be in its path. Ovation, after we left it, was destined for New Caledonia, Mystery Island and associated other islands. I have read that out of about 5 ports of call due to bad weather and conditions, it has only managed one and huge compensation is on its way.

Shoal Bay is part of Port Stephens which in 1770 James Cook named after Sir Phillip Stephens, Secretary to the Admiralty. Of course this is in total deference to the actual previous owners, the Worimi Peoples. Port Stephens is a larger coastal inlet than Sydney Harbour and is largely used for fishing and recreational purposes. Not a great deal is noted until 1934 when Bob Elliott, Alex Kufner and Tony Raper decided Shoal would be a great place to build a club house. During WWII coastal defences were positioned here as well as amphibious training centres for US and Australian forces. Today it is a lovely holiday location and a great place to live. I suspect it is mainly a holiday resort for Australians. To get here yesterday, we drove around Newcastle, strangely also well known for its coal mining just like its namesake. We passed huge open cast mining operations which enable the port of Newcastle to claim the title of the world's largest coal export port shifting some 160 million tonnes of coal per anum, mainly to Asian markets.

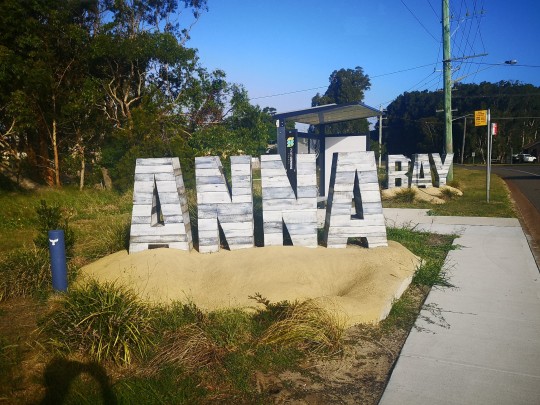

Being a very pleasant, if rather hot day today, it started with an early morning run followed by a trip to the stunning beach. Despite being Sunday, it was nowhere near busy. Home for lunch then out to some of the neighbouring bays. Firstly Fingal Bay. A very comely sort of place where we found a compelling walk across the headland to Fingal Point; a high vantage point where two bays may be viewed at once. There we saw our first goanna lizard. Next bay had to be Anna's Bay with its very large sandy beach, great for windsurfing. The final bay for today was Boatman's Bay where there was no boat but was quite old by Australian standards. A settlement was here in the mid to late 1800s as the strange little cemetery bore testament to. Well, what with all that baying, we struggled back to Shoal for a bottle of SB, and fish & Chips. Barramundi for me and Hake for Martine. Perhaps tomorrow a little more relaxing in this lovely area. An absolute must see if touring in this part of NSW.

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The destination for history

Churchill’s feline dynasties

30 November is Winston Churchill’s birthday. This most celebrated of Prime Ministers would be 142 years old today and, if he was still with us, it is not unreasonable to speculate that wherever he was, there would probably be at least one cat nearby.

Churchill, along with his wife Clementine were animal lovers and usually had a veritable menagerie of cats and dogs about wherever they went – whether that be at their country home Chartwell, Kent, or in No. 10 Downing Street.

‘He loved cats … He always had a cat, if not two,’ one of Churchill’s secretaries recalled. Perhaps the most famous feline legacy that Churchill bequeathed to the nation was that of the Jocks Of Chartwell, a dynasty of six marmalade cats with white bibs and paws who have had run of the historic home since it was given to National Trust after Churchill’s death in 1965.

The first Jock was given to Churchill by his trusted private secretary Sir John ‘Jock’ Colville as an 88th birthday present. Churchill held the original Jock in great affection, so much so that it was rumoured the cat sat on his bed as he died a few years later. After Churchill’s death his family gave Chartwell to the nation, on the condition that a ‘Jock’ would always have the run of the house.

The National Trust has been as good as its word. Chartwell is currently home to Jock VI, who arrived aged seven months from a rescue home in March 2014. According to Chartwell’s website, Jock VI is a ‘mischievous character’ who likes ‘afternoon naps, eating tuna, Persian rugs and cuddles’, but does not favour heights, lightning or opera.

Jock VI at Chartwell

But while the dynasties of Jocks at Chartwell are perhaps the best known of Churchill’s cats, they are perhaps not the most streetwise cats to have been owned by Churchill.

This title probably goes to Churchill’s cat Nelson, whose bold nature so impressed Churchill that he was quickly elevated from the gutter to the very heart of government, No. 10 Downing Street.

Churchill first met Nelson outside the Admiralty buildings in London, where he witnessed the fearless feline chasing a dog down the road. Impressed, he adopted the moggy and named him after Britain’s most famous sailor, Horatio Nelson.

In 1940, Churchill became Prime Minister, taking control of government during the dark days of the Second World War. Nelson came with him to No. 10, and this pugnacious pussy ensured that it not only mainland Europe where conflict raged.

Nelson’s fighting spirit was not diminished by his elevation in society; indeed he quickly took issue with by the Downing Street cat left by departing Prime Minster Neville Chamberlain. Nelson didn’t appreciate sharing the office of Downing Street’s ‘top cat’ with Chamberlain’s mouser (who Churchill unkindly nicknamed ‘The Munich Mouser’ after his master’s derided ‘peace in our time’ speech) and chased the other cat out in short order.

Churchill would no doubt be buoyed that today Whitehall’s cat population is once again on the rise with the high profile mousers of the Cabinet Office, Foreign Office and Treasury – Larry, Palmerston and Gladstone – the darlings of the media; and, in Larry and Palmerston’s case, as equally pugnacious as their 1940s predecessor Nelson.

By Christopher Day

@ 2023 The History Press

Another ‘Jock 'Churchill’s legacy for a marmalade cat to akways live at Chartwell

Thank you❤️

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

I was always doubtful about 'people who get so caught up in fanon that they forget about canon', but hey - that's apparently me.

It just hit me - literally this morning - that in actual canon Felix and Agent A probably NEVER SAW EACH OTHER AGAIN after the interrogation! I'm still having trouble actually conceptualising that.

But also, I'm going to be extremely basic and say:

It’s bad luck always to return, / I shall not see you anymore. / Two silly phrases rise to sway / On height of madness from earth’s floor / I’ll not forget you when I’m gone, / I shall not see you anymore.

Because yeah, for them it was bad luck to return - their return was what landed him in prison - or - depending on the sentence - something I never wanted to think about, but I am thinking about now - maybe facing the wall. And I bet neither of them will forget each other even if they don't ever see each other again.

(the song is from a rock-opera so here's the in-opera version and a separate one and here's also a video from the opera)

Full lyrics - a slightly shortened poem by Voznesensky - translated by William Jay Smith and Vera Dunham:

You will awaken me at dawn

And barefoot lead me to the door;

you’ll not forget me when I’m gone,

you will not see me anymore.

Lord, I think, in shielding you

From the cold wind of the open door:

Ill’ not forget you when I’m gone,

I shall not see you anymore.

The admiralty, the Stock Exchange

I’ll not forget when I am gone,

I’ll not see Leningrad* again,

Its water shivering at dawn.

From withered cherries as they turn,

Brown in the wind, let cold tears pour:

It’s bad luck always to return,

I shall not see you anymore.

Two silly phrases rise to sway

On height of madness from earth’s floor

I’ll not forget you when I’m gone,

I shall not see you anymore.

* for the record - the original poem doesn't say "Leningrad" directly - it's just mentions the Admiralty and the Old Saint Petersburg Stock Exchange - two historical buildings from the city, but for our purposes it works even better, since probably neither of them saw Leningrad again...

#jimち asmr#jim asmr#the canon is thirty three times angstier than what's canon in my head#even the canon compliant parts#Spotify

1 note

·

View note

Text

LOTD: Saddleback Ledge

(from: http://www.ibiblio.org/lighthouse/me.htm)

Saddleback Ledge

1839 (Alexander Parris). Active; focal plane 52 ft (16 m); white flash every 6 s. 42 ft (13 m) ft old-style round granite tower with lantern and gallery, incorporating very cramped keeper's quarters; 300 mm lens. Tower unpainted; lantern painted black. Fog horn (blast every 10 s). All other light station buildings demolished in the 1960s. Anderson has a good page for the lighthouse, Lighthouse Digest has D'Entremont's article on its history, Trabas has Boucher's closeup photo, Marinas.com has aerial photos, Huelse has a historic postcard view showing the additional keeper's quarters that were formerly attached, and Google has a satellite view. This historic tower is the oldest surviving waveswept lighthouse in the U.S. It was designed by Alexander Parris (1780-1852), one the country's best known architects at the time. In 2009 the lighthouse became available for transfer under NHLPA but it appears that it was later withdrawn. Located on a tiny, isolated island in the mouth of Isle au Haut Bay, between Isle au Haut and Vinalhaven. Accessible only by helicopter; it can be seen by boat, but it is almost impossible to land on the rocky island. Site and tower closed. Owner/site manager: U.S. Coast Guard. ARLHS USA-716; Admiralty J0064; USCG 1-3325.

(photo found here; ©Boucher)

0 notes

Text

A light on a reef

Until the end of the 17th century one of the threats facing shipping heading to Plymouth on the southern coast of England was the isolated and treacherous Eddystone reef, 23km directly offshore. Much of the hazard is underwater, creating complex currents, and extraordinarily high seas are often kicked up when conditions are very windy. In 1620 Captain Christopher Jones, master of Mayflower described the reef: "Twenty-three rust red [...] ragged stones around which the sea constantly eddies, a great danger [...] for if any vessel makes too far to the south [...] she will be swept to her doom on these evil rocks." As trade with America increased during the 1600s a growing number of ships approaching the English Channel from the west were wrecked on the Eddystone reef.

King William III and Queen Mary were petitioned that something be done about marking the infamous hazard. Plan to erect a warning light by funding the project with a penny a ton charge on all vessels passing initially foundered. Then an enterprising character called Henry Winstanley stepped forward and took on the most adventurous marine construction job the world had ever seen. Work commenced on the mainly wooden structure in July 1696. England was again at war, and such was the importance of the project that the Admiralty provided a man-o-war for protection.

The Winstanley Lighthouse, by English School, 17th century (x)

On one day, however, HMS Terrible did not arrive and a passing French privateer seized Winstanley and carried him off to France. When Louis XIV heard of the incident he ordered his release. " France is at war with England, not humanity," said the King. Winstanley's was the first lighthouse to be built in the open sea. It was a true feat of human endeavour. Work could only be undertaken in summer and for the first two years nothing could be left on the rock or it would be swept away. There was some assistance from Terrible in transporting the building materials, but much had to be rowed out in an open four-oared boat in a journey that could take nine hours each way. Winstanley's lighthouse was swept away after less that five years, during the great storm of 1703.

John Rudyerd's wooden lighthouse of 1708, by Issac Sailmaker, c. 1708 (x)

Winstanley was in it at the time supervising some repairs- he had said that he wished to be there during " the greatest storm that ever was." The next lighthouse was built by John Rudyerd and lit in 1709. Also made largely of timber and with granite ballast, it gave good service for nearly half a century until destroyed by fire in 1755. During the blaze the lead cupola began to melt, and as the duty keeper, 94- old Henry Hall, was throwing water upwards from a bucket he accidentally swallowed 200g of the molten metal. No one believed his incredible tale, but when he died 12 days later doctors found a lump of lead in his stomach.

Smeaton's Eddystone Lighthouse, by John Lynn (active 1826-1869) (x)

John Smeaton, Britian's first great civil engineer, was the next to rise to the challenge of Eddystone. He took the English oak as his design inspiration - a broad base narrowing in a gentle curve. The 22m high lighthouse was built using solid discs of stone dovetailed together. Work began in 1756, and from start to finish the work took three years, nine weeks and three days. Small boats transported nearly 1000 tons of granite and Portland stone along with all the equipment and men.

Sir James N. Douglass's Eddystone Lighthouse, Plymouth, England, photochrome print, c. 1890–1900. The remnants of John Smeaton's lighthouse are at left. (x)

The Smeaton lighthouse stood for over 100 years. In the end it was not the lighthouse that failed; rather that the sea was found to have eaten away the rock beneath the structure. In 1882 it was dismantled and brought back to Plymouth, where it was re-erected stone on the Hoe as a memorial, and where it still stands.

The Eddystone lighthouse today (x)

It had already been replaced by a new lighthouse, twice as tall and four and a half times as large, designed by James Douglas, which now gives mariners a beacon of light visible for 22 nautical miles (40,78km).

80 notes

·

View notes

Text

Greenwich

Everyone knows that you can’t really see much in Greenwich United Kingdom, UK until you get past the town of Greenwich. However, if you know where to look and have a little patience, you will be rewarded with some truly magical spots. Greenwich is home to a number of beautiful historical buildings and interesting places, but there are also some hidden gems that most people don’t know about. Check this out

St Mary’s Church, Old Greenwich

St Mary’s Church is an ancient church in Old Greenwich, London, England. It is a Grade I listed building and a notable example of Tudor architecture. St Mary’s Church is the only remaining medieval church in Greenwich. The church is set on a hill overlooking the River Thames. It is about a mile west of the centre of London. The church was originally built during the reign of Henry the Seventh as a chapel of ease for the town’s new parish church of St Lawrence, Langdon. The church was consecrated in 1425. A few additions have been made over the centuries, but it is basically the same structure today. It is built of red brick with freestone dressings, and has two towers at the west end which are Saxon in date. Inside the church there are a number of old gravestones and monuments, including to Sir John Gresham, the founder of the Royal Exchange in London. There is a beautiful organ which is played regularly.

The Old Royal Naval College

The Old Royal Naval College is a former Royal Naval College at Greenwich, now used as offices by the Royal Navy. It is situated on the Greenwich Peninsula overlooking the River Thames. The College was founded in 16 HRM (1805) by King William IV, and was opened by Queen Victoria in 1841. Its buildings were originally designed by Sir William Tallett. The College’s buildings are now home to the Admiralty Office and other Government departments, but the Old Royal Naval College and its grounds are maintained and administered by the City of London Corporation as part of London’s UNESCO World Heritage Site, of which it is part. The college is referred to colloquially as just “Greenwich” by the Royal Navy and other Government departments, even though it is located some miles west of the town centre.

Greenwich Park

Greenwich Park is a 1.9 hectare public park located in the East End of London, England. It is the smaller of the two parks within the Greenwich Area of the London Borough of Greenwich. It is located between the River Thames and the North Orbital Road/A2/M2 motorway. It is managed by the London Borough of Greenwich. The park is situated on the southern side of the Greenwich peninsula. It is bordered by the River Thames to the south, and the North Orbital Road/A2/M2 motorway to the north. To the east is the A102 Western Avenue, to the west is the A2 and to the south are the railway tracks of the London and Greenwich Railway and the Millennium Dome site. The park contains playing fields, a riverside walk, a café and a boat house. The park is popular with walkers, joggers, dog walkers and cyclists.

Thomas Wright House

Thomas Wright House is a Georgian house in the Royal Borough of Greenwich, London. It is located on Thomas Wright Place in the Old Royal Naval College. It is Grade II listed and is now used as offices by the Royal Navy. The house was built in 1727 for Thomas Wright, Clerk of the Navy, and was one of the earliest buildings on the Greenwich Peninsula. It was designed by William Tallett. The house is built of red brick with freestone dressings, including a pillared and panelled portico, and a fanlight in the Saloon.

The View from the Cutty Sark

The View from the Cutty Sark is a viewpoint located on an embankment adjacent to the Cutty Sark, Greenwich. The Cutty Sark, a British passenger ship that was the last of her kind, was built in the 19th century and served as a convoy escort during World War II. The Cutty Sark is now a museum, although it is still open to the public. The embankment adjacent to the Cutty Sark is now a popular viewpoint and a popular spot for wedding photographs. The embankment is also a popular spot for photographers on public holidays, especially during the summer months. The viewpoint is located in Greenwich Park, which is located in the Royal Borough of Greenwich and is the largest park in London.

Conclusion

Greenwich is a beautiful place with plenty of history and a few hidden spots that are well worth exploring. We have highlighted the best spots in Greenwich United Kingdom, UK to help you get a better sense of the town. Depending on your interests, you will be able to see some of the historical buildings or enjoy some of the natural beauty of the area. You will also be able to experience the culture of Greenwich United Kingdom, UK by visiting one of the many restaurants or pubs. Browse next article

Originally published here: https://forestray.dentist/london/greenwich/

0 notes

Text

6 Signs your Chimney Liner Needs to be Replaced

Some consider chimney liners to be the unsung hero of the chimney system. Tucked within the brick masonry, hidden from plain sight, your chimney liner silently improves the safety of your fireplace with no pomp and circumstance. A true behind-the-scenes component of your chimney system, how would know when this vital structure needs to be replaced? Here are six tell-tale signs from the CCP-certified pros at Admiralty Chimney.

What does my chimney liner do?

A chimney liner keeps toxic gas, smoke and creosote from entering your home and prevents the chimney structure from being damaged by heat. These liners are so important that building codes require them in fireplaces. If a liner is missing or damaged, it can lead to serious consequences. There are certain situations that suggest a liner needs replacing, such as:

There is an excessive amount of efflorescence on your bricks.

Efflorescence, a white, powdery substance on the surface of your bricks, is a sign that your flue liner is cracked or has lost its seal. This is a serious condition that will cause rapid brick and mortar deterioration.

There are broken shards or flakes on your fireplace floor.

Older clay chimney liners will start to crack over time, leaving pieces of clay in your hearth. Without having an expert take care of a cracked liner, it increases the risk of chimney fires.

The fire is producing room-filling smoke.

A chimney liner is responsible for moving smoke outside the home. If your home is smoky, it could be a sign that your liner needs to be replaced. This issue can lead to a number of health problems including carbon monoxide poisoning, asthma attacks and other respiratory issues.

Your chimney hasn’t been inspected.

If you can’t remember the last time you had professional technicians inspect your chimney, then it has been too long. Arrange for a safety inspection to examine and assess the condition of your chimney and liner.

Your chimney liner is old.

Certain types of chimney liners could last around 20 years, while budget liners could only last five years. Additionally, if your family uses the fireplace often, then the frequent wear and tear can cause the flue liner to deteriorate quicker.

You’ve purchased a new energy-efficient heating system.

When you replace your heating system for a high-efficiency model, or to a type of heater that you haven’t used before, it is a good idea to get a new liner installed. An older chimney liner may not provide proper ventilation for a new system.

What do I do if I’m unsure about needing a liner replacement?

Scheduling a professional chimney inspection is the best way to let you know when you need a new liner. A CCP-certified chimney technician can alleviate or confirm your concerns by taking a thorough look at the condition of your liner and chimney system. If you suspect that it’s time for a chimney liner replacement, contact Admiralty Chimney for an inspection.

Chimney Liner Installation, Service, Repair in NH and MA

If you’re looking for certified chimney inspections to determine the age and condition of your chimney liner, reach out to the CCP-certified pros at Admiralty Chimney. We are a full-service fireplace and chimney company. Contact us today to learn more.

Powered by Sprout

0 notes

Photo

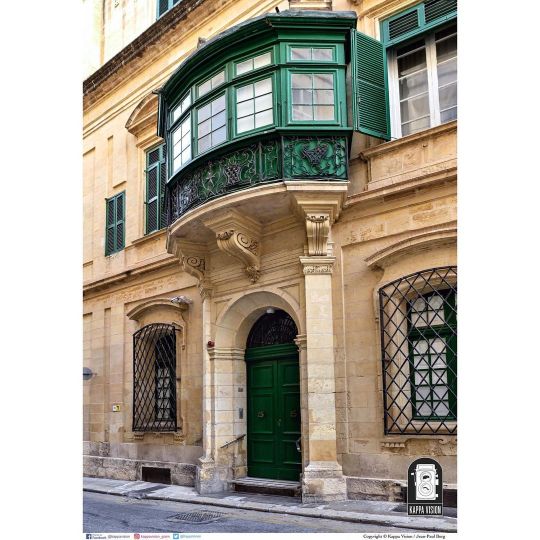

Maison Demandols was built in the early 18th century probably on the design of a follower of the famous Baroque architect Romano Carapecchia. A noteworthy feature is the original convex open wrought iron balcony incorporating a closed wooden balcony, which was installed at a later period. MAISON DEMANDOLS Maisons Demandols is located in South Street, opposite the Admiralty House (presently the office of the Attorney General) and opposite to where the Auberge de France, no longer in existence, once stood. One of the three Maison Demandols houses had the misfortune of being destroyed by a German bomb during the Second World War and on its site a building was erected which is completely out of harmony with the two remaining houses. The Baroque Maison Demandols building originally consisted of three houses having façades in the same architectural treatment. In 1652 these three houses were acquired by Balthazar de Demandols, who was the Provencal Bailiff and Captain-General of the Galleys of the Order of St. John, twice in 1650 and 1657. The houses are named after him. In 1800 the property was acquired by the Monte di Pietà. The building has two entrances at South Street (Triq Nofsinhar) and another round the corner at Old Mint Street (Triq Żekka). The houses are mainly on three storeys. A CARAPECCHIA BUILDING? Carapecchia came to Malta from Italy in 1707. The architect was involved in other famous projects of the era: the church of St. Catherine of the Langue of Italy, the church of St. Barbara, the church of St. James, and most famously the Manoel Theatre, all in Valletta. Leonard Mahoney attributes the design of Maison Demandols to a follower of Romano Carapecchia. PRESENT DAY The building was damaged by aerial bombardment during the World War II and was reconstructed by the Public Works Department although, as mentioned, one of the three houses was lost. The building is currently the Ministry of Finance. Mepa scheduled Maisons Demandols as a Grade 1 national monument as per Government Notice No. 276/08 in the Government Gazette dated March 28. (at Valletta, Malta) https://www.instagram.com/p/CgWxFAPo1KF/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

0 notes

Photo

On July 3rd 1728 Robert Adam, the Scottish architect, furniture and interior designer, was born.

Robert Adam was the son of the established architect William Adam, and followed him into the family practice. In 1754 he embarked on a ‘Grand Tour’, spending five years in France and Italy visiting classical sites and studying architecture. On his return Adam established his own practice in London with his brother James. Although classical architecture was already becoming popular, Adam developed his own style, known as the Adam style or Adamesque. This style was influenced by classical design but did not follow Roman architectural rules as strictly as Palladianism did.

As Adam was more often than not asked to renovate existing buildings much of his work was concerned with interiors. He was obsessive over every detail and designed everything himself down to plasterwork and fireplaces. He moved beyond Roman Style and was influenced by Greek, Byzantine and Italian Baroque design.

Probably his best known work for us Scots is Register House at the East end of Princes Street, my favourite though is Gosford House in East Lothian, back in Edinburgh he designed the Old Quad of the University on South Bridge and of course you do have to admire Admiralty Arch at The Mall in London, which is in the process of being converted into a hotel.

The pics include a wine cooler designed by Adan, and a cabinet, it shows he was more than an architect.

13 notes

·

View notes