#Lyudmila Feyginova

Photo

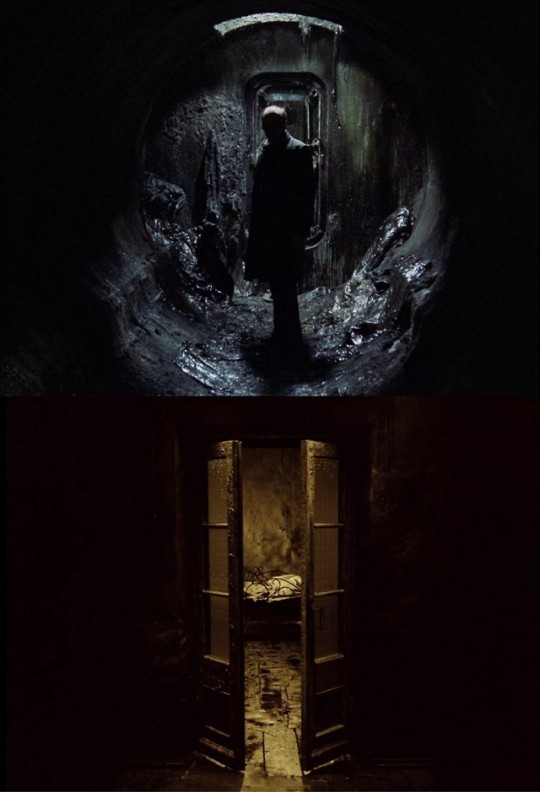

Mirror (Andrei Tarkovsky, 1975)

Cast: Margarita Terekhova, Oleg Yankovskiy, Filipp Yankovskiy, Ignat Daniltsev, Nikolay Grinko, Alla Demidova, Yuriy Nazarov, Anatoliy Solonitsyn, Larisa Tarkovskaya, Innokentiy Smoktunovskiy (voice). Screenplay: Aleksandr Misharin, Andrei Tarkovsky, Arseni Tarkovskiy (poems). Cinematography: Georgi Rerberg. Production design: Nikolay Dvigubskiy. Film editing: Lyudmila Feyginova. Music: Eduard Artemyev.

What are the limits of narrative cinema? If, indeed, Mirror is narrative – that question needs to be developed in more ways than I can go into here. I concede that it is “poetic,” including the fact that Arseniy Tarkovskiy, the director’s father, reads his own poems in the film, and there are scenes of extraordinary beauty, the work of cinematographer Georgi Rerberg. But is that all we should ask of a film? It’s easy to say that Andrei Tarkovsky’s film is non-linear, jumping back and forth in time with no clues about when and where we are in any given moment. Even the switches from black-and-white to color turn out to be red herrings if you’re trying to sort out chronology. There is a fine line between frustration and stimulation, and Tarkovsky dances along it as we the viewers follow him. The film has to be understood as a memory piece in which Alexei, a man on his deathbed, recalls his childhood in Russia before, during, and after World War II. His memories include his mother, Maria, and his wife, Natalia, both played beautifully by Margarita Terekhova. Similarly, Ignat Daniltsev plays both the young Alexei and his son, Ignat. In addition to the actor Innokentiy Smoktunovskiy’s voiceover as the dying Alexei, there is newsreel footage from the wartime and postwar periods, along with bits of fantasy and surrealism. I would like to say that Mirror is hypnotic, because it begins with a scene in which a therapist uses hypnotism to try to cure a young man of a speech impediment, but that oversimplifies the effect of the film. In the end, I have to concede to the consensus on the greatness of Mirror: It took 31st place in the 2022 Sight and Sound critics poll of the greatest films of all time, and an astonishing 8th place in the directors’ poll.

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Mirror (Andrei Tarkovsky, 1975).

#mirror (1975)#zerkalo (1975)#andrei tarkovsky#georgi rerberg#lyudmila feyginova#nikolay dvigubskiy#nelli fomina#a. merkulov#yuri potapov#margarita terekhova#oleg yankovskiy#filipp yankovskiy

625 notes

·

View notes

Photo

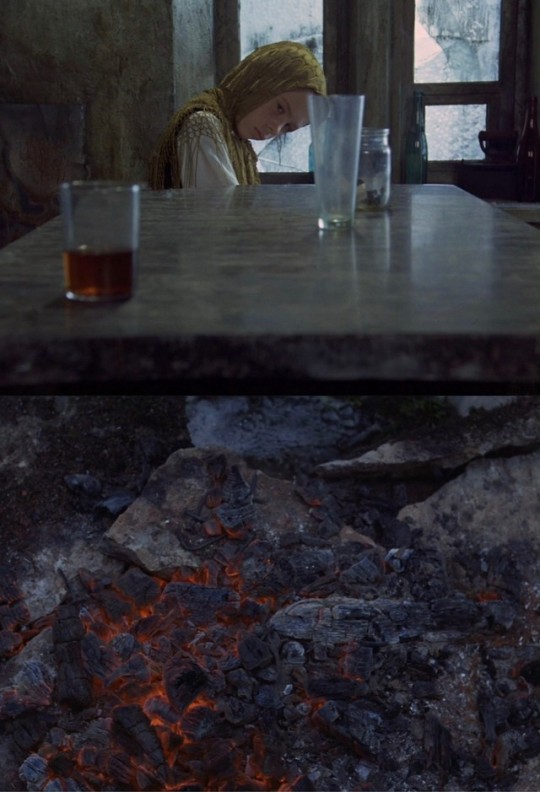

If a well is really deep, you can see a star down there even in the middle of a sunny day.

Ivan's Childhood (Ivanovo detstvo), Andrei Tarkovsky (1962)

#Andrei Tarkovsky#Mikhail Papava#Nikolay Burlyaev#Valentin Zubkov#Evgeniy Zharikov#Stepan Krylov#Nikolay Grinko#Dmitri Milyutenko#Valentina Malyavina#Irina Tarkovskaya#Vadim Yusov#Vyacheslav Ovchinnikov#Lyudmila Feyginova#1962

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Solaris, directed by Andrei Tarkovsky, screenplay by Andrei Tarkovsky and Fridrikh Gorenshteyn, cinematography by Vadim Yusov, music by Eduard Artemev, and edit by Lyudmila Feyginova and Nina Marcus.

The key to great filmmaking is how you utilize your cinematic style to absorb the audience into a unique experience that can only be created through the art of cinema. Harmonizing specificity of vision and economy of meaning results in great filmmaking, meaning that your artistic voice plus finely-tuned decision-making in details equals a mindful use of your cinematic style. All great films encapsulate the filmmaker’s struggle to express him or herself within the confines of production and his or her feelings of what is and what is not meaningful to the film and the path to implementing what is in the most mindful way to the storytelling of the film.

In Sculpting in Time, Andrei Tarkovsky shares a striking thought on cinema relevant to this philosophy on great filmmaking: “I love cinema. There is still a lot that I don't know: what I am going to work on, what I shall do later, how everything will turn out, whether my work will actually correspond to the principles to which I now adhere, to the system of working hypotheses I put forward. There are too many temptations on every side: stereotypes, preconceptions, commonplaces, artistic ideas other than one's own. And really it's so easy to shoot a scene beautifully, for effect, for acclaim...But you only have to take one step in that direction and you are lost. Cinema should be a means of exploring the most complex problems of our time, as vital as those which for centuries have been the subject of literature, music and painting. It is only a question of searching, each time searching out afresh the path, the channel, to be followed by cinema. I am convinced that for any one of us our filmmaking will turn out to be a fruitless and hopeless affair if we fail to grasp precisely and unequivocally the specific character of cinema, and if we fail to find in ourselves our own key to it.”

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Mirror (Zerkalo)

BBBB (out of 5) This one is Andrei Tarkovsky for advanced students. A non-linear narrative structure, little explanation of context for many scenes and only the barest suggestion of concrete reality versus dream logic means that those being initiated into the director’s wondrous commitment to ephemeral artistry will be baffled and bored. It is, at its essence, the ruminations of an aging, dying…

View On WordPress

#Aleksandr Misharin#Alla Demidova#Anatoliy Solonitsyn#Andrei Tarkovsky#Arseniy Tarkovskiy#Ángel Gutiérrez#Diego García#E. Del Bosque#Eduard Artemev#Erik Waisberg#Filipp Yankovskiy#Georgi Rerberg#Ignat Daniltsev#Innokentiy Smoktunovskiy#L. Correcer#Larisa Tarkovskaya#Lyudmila Feyginova#Margarita Terekhova#Mosfilm#Nelli Fomina#Nikolay Dvigubskiy#Nikolay Grinko#Oleg Yankovskiy#Tamara Ogorodnikova#Tamara Reshetnikova#Tatiana Del Bosque#Teresa Del Bosque#Teresa Rames#USSR#Yuri Sventisov

0 notes

Video

vimeo

Editing as Punctuation in Film from Max Tohline on Vimeo.

In January 2014 Kathryn Schulz published an article in Vulture called "The Five Best Punctuation Marks in Literature."

Link: vulture.com/2014/01/best-punctuation-marks-literature-nabokov-eliot-dickens-levi.html

It got me thinking about what the five best "punctuation marks" in film might look like. I wanted to assemble a video essay with a rapidfire list of nominees of great moments of editing-as-punctuation in film. But as I started putting it together, the project grew into a twofold piece: an analysis of and response to Schulz's article as well as an attempt to spur new insights about editing by examining it through the metaphor of punctuation.

So, here it is: 20 minutes long, clips from 100 films (101 if you count that Woody Allen quotes Duck Soup in Hannah and her Sisters), and, I hope, an inspiration to anyone else who loves film on a formal level and believes, as Bazin did, that the language of cinema isn't done being invented yet.

Thanks to Kathryn Schulz for sending me down this wonderful rabbit hole of thought, and to the editors (in order of their cuts): Sally Menke, Buster Keaton, Abel Gance, Yelizaveta Svilova & Dziga Vertov, Michael Snow, Jonathan Amos & Paul Machliss, Harry Gerstad, William Reynolds & Peter Zinner, David E. Blewitt & Robert K. Lambert & David Newhouse, Sergei Eisenstein, Daniel Rezende, Valeriya Belova, Richard Pearson & Christopher Rouse, Lou Lombardo, Marguerite Beaugé & Carl Theodor Dreyer, George Tomasini, D.W. Griffith & James Smith & Rose Smith, Lev Kuleshov, Charles Chaplin & Willard Nico, Ron Fricke & Alton Walpole, Sam O'Steen, Edgar Adams & Edward L. Cahn, Ray Lovejoy, Siro Asteni, Anne V. Coates, Robert Wise, Susan E. Morse, LeRoy Stone, Ken Eluto, Spike Lee, Jerome Thoms, Lyudmila Feyginova, Peter Przygodda, Ferris Webster, Andrew Weisblum, Léonide Azar feat. Anton Walbrook, Alan Heim, Claudia Castello & Michael P. Shawver, Michal Leszczylowski & Andrei Tarkovsky, Ralph Rosenblum, William Hornbeck, Barbara McLean, William Chang & Kit-Wai Kai & Chi-Leung Kwong, Véronique Parnet, Kim Hyeon, Andreas Prochaska, Mary Sweeney, John Smith, Jolanda Benvenuti, Harold F. Kress & Argyle Nelson Jr. & J. Frank O'Neill, Florence Eymon, Nicholas T. Proferes, Marie-Josèphe Yoyotte, Mohsen Makhmalbaf, Yoshiyasu Hamamura, Cécile Decugis, Joe Bini, Robert Leighton, Milton Carruth, Jay Rabinowitz, Owen Marks, Ted Cheesman, George Tomasini (again), Blanche Sewell, Georges Méliès, Reginald Mills, Siv Lundgren, Thelma Schoonmaker (finally!), Kôichi Iwashita, Alex O'Flinn, Kirk Baxter, Peter Kubelka, Paul Sharits, Chris Marker, Jean Ravel, Roderick Jaynes (Ethan and Joel Coen), Sharon Rutter, Miroslav Hájek, Fernand Léger & Dudley Murphy, Melvin Van Peebles, Martin Arnold, Bruce Conner, Walter Murch & Richard Chew, and Yelizaveta Svilova & Dziga Vertov again. Plus unseen contributions from Jacqueline Sadoul, Jim Miller & Paul Rubell, Monique Bonnot, Ralph Foster & Stephen Perkins & Andrew Weisblum, Verna Fields, Jack Murray, Daniel Mandell, Françoise Collin, Solange Leprince, Patricia Canino, Nelly Quettier, Matt Chesse, George McGuire, John Seabourne Sr., Takis Davlopoulos & Giorgos Triandafyllou, and a few VFX teams, too.

For the full list of films featured, click here: 10oclockdot.tumblr.com/post/129417606958

NEW: Pablo Ferreira (vimeo.com/pabloferreira) has just graciously created Portuguese subtitles for this video!

Plus: Héctor Aguilar Rivas's (vimeo.com/user24306664) Spanish subtitles are still here and still great.

Also: Turkish speakers, please enjoy this TURKISH DUB of Editing as Punctuation in Film, lovingly prepared by Münif Çankaya: vimeo.com/146388456

And I'm still grateful that Editing as Punctuation in Film was named THRICE as one of the best video essays of 2015 by leading critic/curators in Fandor's poll. Thank you!

fandor.com/keyframe/poll-the-best-video-essays-of-2015

0 notes

Text

Anatoliy Solonitsyn in Andrei Rublev (Andrei Tarkovsky, 1966)

Cast: Anatoliy Solonitsyn, Nikolay Grinko, Nikolay Sergeyev, Nikolay Burlyaev, Ivan Lapikov, Irma Raush, Yuriy Nazarov, Yuriy Nikilin, Rolan Bykov, Mikhail Kononov. Screenplay: Andrey Konchalovskiy, Andrei Tarkovsky. Cinematography: Vadim Yusov. Production design: Evgeniy Chernyaev. Film editing: Tatyana Egorycheva, Lyudmila Feyginova, Olga Shevkunenko. Music: Vyacheslav Ovchinnikov.

Has any filmmaker ever made more eloquent use of the widescreen format than Andrei Tarkovsky does in Andrei Rublev? It was a process developed by Hollywood to help win its war with television -- bigger naturally assumed to be better. In Hollywood, it usually went hand-in-hand with color, and although the various widescreen processes -- Cinerama, Cinemascope, VistaVision, etc. -- were used in black-and-white films, they often feel out of place today. A case in point: The Diary of Anne Frank (George Stevens, 1959), which won an Oscar for the cinematography of William C. Mellor, but which seems to cry out for a format less expansive than CinemaScope, in which the Frank family's attic loses its cramped and confined essence. Andrei Rublev was filmed in a process called Sovscope, which like CinemaScope used anamorphic lenses to produce a 2.35:1 aspect ratio. Tarkovsky and cinematographer Vadim Yusov artfully work with the expanse of the screen, not shying away from closeups but also doing extraordinary movement with the camera. One of the earliest scenes takes place in the barn in which Rublev and his fellow artist-monks take shelter from the rain. We are given an astonishing 360-degree pan inside the barn, circling from the monks to the other denizens of the shelter and back to the monks, a study in faces that establishes one of the film's major subjects: the nature of Russian humanity, which also becomes an abiding concern of Rublev's. (I think there's a witty acknowledgment of the nature of widescreen in that the peep-hole cut into the wall of the bar seems to have the same aspect ratio as the film.) And in the concluding sequence, there is a magnificent pan from the gates of the walled city of Vladimir below and the emerging procession up to the structure that holds the newly cast bell, where Boriska (Nikolay Burlyaev) waits anxiously. Andrei Rublev is one of those films I can't help rewatching; even though (or perhaps because) it's slow and challenging, it more than repays frequent viewings. Tarkovsky is not a director to be taken lightly, and the moment you begin to be lulled by the magnificence of Yusov's cinematography or Vyacheslav Ovchinnikov's score, the director is likely to shock you with images of cruelty and brutality but also of beauty that make you sit upright. A "trigger warning" might be especially needed for lovers of animals, given the harshness with which they are occasionally treated: There is a scene with a cow on fire that will likely haunt me for a long time.* But all the unpleasantness in the film is in service of a story about the persistence of the Russian people and the transcendence of art. Anatoliy Solonitsyn, who plays Rublev, looks a bit like Viggo Mortensen, and recalls for me the tormented masculinity you find in some of Mortensen's performances. Another standout performance is given by Tarkovsky's wife, billed as Irma Raush, as the "holy fool" Durochka, whom Rublev saves from a massacre by the Tatars by killing the assailant -- leading Rublev to atone by giving up his painting and taking a vow of silence. The last section of the film is given over to young Boriska, played by Nikolay Burlyaev, the astonishing Ivan in Tarkovsky's Ivan's Childhood (1962), who takes on the task of casting a church bell despite the suggestion that he will be murdered by the tyrannical Grand Duke (Yuriy Nazarov) if he fails. Although the film is in black-and-white, it concludes with a breathtaking color sequence in which Rublev's paintings are shown in close-up. To my mind, this final ecstatic survey of Rublev's work is the only section in which Tarkovsky is thwarted by the widescreen process: Rublev's paintings had an aspiring verticality that is at odds with the dimensions of the screen.

*The scene, I learned, on a recent re-viewing of the film, doesn't exist in all versions. In addition to versions made by Soviet censors, Tarkovsky himself made two: His original version ran 205 minutes, but he also made a "final cut" that runs 183 minutes.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Aleksandr Kaidanovsky in Stalker (Andrei Tarkovsky, 1979)

Cast: Aleksandr Kaidanovsky, Anatoliy Solonitsyn, Nikolay Grinko, Alisa Freindlich, Natasha Abramova, Fame Jurno, E. Kostin, Raymo Rendi. Screenplay: Arkadiy Strugatskiy, Boris Strugatskiy, based on their novel. Cinematography: Aleksandr Knyazhinskiy, Georgi Rerberg. Production design: Aleksandr Boym, Andrei Tarkovsky. Film editing: Lyudmila Feyginova. Music: Eduard Artemev.

Andrei Tarkovsky's dystopian fantasy has something of the flavor of a Russian folk tale. The archetypes are there: the perilous quest, the trio of seekers, the anagnorisis, the catharsis, the disillusioned return. The title character, splendidly played by Aleksandr Kaidanovsky, is not a "stalker" in the current sexual sense but rather a man who guides others into the Zone, a mysterious area cordoned off from the rest of the world by the military. In the Zone, the Stalker says, is a Room that fulfills each person's secret desires. The men he guides in the film are a cynical Writer (Anatoliy Solonitsyn) and an ambitious Professor (Nikolay Grinko) -- archetypes of art and science, who throughout their journey make the cases for their respective world-views. The film begins in monochrome -- sometimes stark black-and-white, sometimes a bilious orange -- in the Stalker's bedroom, where he shares a bed with his wife (Alisa Freindlich) and his young daughter, whom they call Monkey (Natasha Abramova). Before he leaves to meet the Writer and Professor, the wife chides him for taking on another dangerous mission. To get to the Zone, they have to pass through a heavily guarded section, and when they reach it, the film turns to color. But the Zone is no Oz, despite the obvious allusion. It is distinguished from the bleak industrial outside world by an abundance of vegetation that covers not only ruins of a former industrial society but also the tanks, weaponry, and corpses of the military that tried to invade and conquer it. The Zone is also magical, continually frustrating attempts to move through it and reach the Room, but the Stalker has learned how to anticipate and avoid its tricks. He says that as a Stalker he is forbidden to enter the Room, but the truth is that he knows the fate of an earlier Stalker, called Porcupine, who did enter it. Tarkovsky's usual long takes demand actors of considerable skill, and all of the company possess it. Although Freindlich's role as the wife is a smaller one, since she doesn't accompany them on the journey, she has a compelling scene at the film's end that's a master class in how to deliver a monologue. The shoot was a legendarily troubled one, since the locations were actual badly polluted industrial ruins, and many of the crew grew ill from the toxins in the abandoned chemical plant -- there are those who claim that the deaths from lung cancer of Tarkovsky, his wife, Larisa, who was a second-unit director, and Solonitsyn were a result of exposure to chemicals during the filming of Stalker. In fact, much of the film was shot at least twice, after cinematographer Georgi Rerberg was fired and replaced with Aleksandr Knyazhinsky, doubling the exposure of many of the cast and crew. Backstory aside, Stalker is a fascinating glimpse into Tarkovsky's mind and milieu.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Ivan's Childhood (Andrei Tarkovsky, 1962)

Cast: Nikolay Burlyaev, Valentin Zubkov, Evgeniy Zharikov, Stepan Krylov, Nikolay Grinko, Dmitri Milyutenko, Valentina Malyavina, Irina Tarkovskaya, Andrey Konchalovskiy. Screenplay: Vladimir Bogomolov, Mikhail Papava, based on a story by Vladimir Bogomolov. Vadim Yusov. Production design: Evgeniy Chernyaev. Film editing: Lyudmila Feyginova. Music: Vyacheslav Ovchinnikov.

There are scenes in Ivan's Childhood that would work in the hands of only Andrei Tarkovsky. The famous scene in the birch forest, in which Kholin (Valentin Zubkov) straddles a trench and kisses Masha (Valentina Malyavina) while dangling her over it is completely extraneous to Ivan's story, as are almost all the scenes in which Masha, the physician's assistant, appears. And Tarkovsky never falls into the trap of sentimentality in the dream sequences, including the film's ending. In fact, I think it's a mistake to call them "dream sequences" -- they mostly avoid the conventions of movie dreams like odd angles or camera tricks or surreal elements. They're really memory pieces, explorations of the other side of Ivan's childhood, the innocent years of peace, poetically interpolated into the harshness of war. In fact, the "real" sequences are often more dreamlike than the memories: the dizzying ghostlike trunks of the birch trees, the flares falling silently like meteorites, the spiky war ruins that threaten to impale. It's a heartbreaking film because Tarkovsky refuses to pull out all the melodramatic stops but lets his images speak for themselves and because Nikolay Burlyaev performs with such conviction as Ivan, in one of the greatest performances by a child ever captured on film. It's probably the most poetic war film ever made because the war recedes into the background as a thing remembered.

0 notes

Photo

Don't turn a scientific problem into a common love story.

Solaris (Solyaris), Andrei Tarkovsky (1972)

#Andrei Tarkovsky#Fridrikh Gorenshteyn#Natalya Bondarchuk#Donatas Banionis#Jüri Järvet#Vladislav Dvorzhetskiy#Nikolay Grinko#Anatoliy Solonitsyn#Olga Barnet#Vitalik Kerdimun#Olga Kizilova#Tatyana Malykh#Vadim Yusov#Eduard Artemev#Lyudmila Feyginova#Nina Marcus#1972

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Let them believe in themselves. Let them be helpless like children, because weakness is a great thing, and strength is nothing. When a man is just born, he is weak and flexible. When he dies, he is hard and insensitive. When a tree is growing, it's tender and pliant. But when it's dry and hard, it dies. Hardness and strength are death's companions. Pliancy and weakness are expressions of the freshness of being. Because what has hardened will never win.

Stalker, Andrei Tarkovsky (1979)

#Andrei Tarkovsky#Arkadiy Strugatskiy#Boris Strugatskiy#Aleksandr Kaydanovskiy#Anatoliy Solonitsyn#Nikolay Grinko#Alisa Freyndlikh#Natalya Abramova#Faime Jurno#E. Kostin#Raymo Rendi#Aleksandr Knyazhinskiy#Eduard Artemev#Lyudmila Feyginova#1979

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

You just spoke of Jesus. Perhaps he was born and crucified to reconcile God and man. Jesus came from God, so he is all-powerful. And if He died on the cross it was predetermined and His crucifixion and death were God's will. That would have aroused hatred not in those that crucified him but in those that loved him if they had been near him at that moment, because they loved him as a man only. But if He, of His own will, left them, He displayed injustice, or even cruelty. Maybe those who crucified him loved him because they helped in this divine plan.

Andrey Rublev, Andrei Tarkovsky (1966)

#Andrei Tarkovsky#Andrey Konchalovskiy#Anatoliy Solonitsyn#Ivan Lapikov#Nikolay Grinko#Nikolay Sergeev#Nikolay Burlyaev#Irina Tarkovskaya#Yuriy Nazarov#Yuriy Nikulin#Rolan Bykov#Nikolay Grabbe#Mikhail Kononov#Vadim Yusov#Vyacheslav Ovchinnikov#Tatyana Egorycheva#Lyudmila Feyginova#Olga Shevkunenko#1966

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Andrei Rublev, directed by Andrei Tarkovsky, screenplay by Andrey Konchalovskiy and Andrei Tarkovsky, cinematography by Vadim Yusov, music by Vyacheslav Ovchinnikov, and edit by Tatyana Egorycheva, Lyudmila Feyginova, and Olga Shevkunenko.

Follow @a.bittersweet.life for your daily dose of cinematic inspiration.

79 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Mirror, directed by Andrei Tarkovsky, screenplay by Andrei Tarkovsky and Aleksandr Misharin, cinematography by Georgi Rerberg, music by Eduard Artemev, and edit by Lyudmila Feyginova.

“Before defining art—or any concept—we must answer a far broader question: what’s the meaning of man’s life on Earth? Maybe we are here to enhance ourselves spiritually. If our life tends to this spiritual enrichment, then art is a means to get there. This, of course, in accordance with my definition of life. Art should help man in this process.” Art should help mankind in this process that Tarkovsky describes as spiritual enrichment. One of the gifts of art is its ability to present meaning to our experience of life. That is to say, art should help mankind rise toward the actualization of our best selves. As Tarkovsky writes in Sculpting in Time, “Art is a meta-language, with the help of which people try to communicate with one another; to impart information about themselves and assimilate the experience of others. Again, this has not to do with practical advantage but with realizing the idea of love, the meaning of which is in sacrifice: the very antithesis of pragmatism.”

28 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Stalker, directed by Andrei Tarkovsky, screenplay by Andrei Tarkovsky, Arkadiy Strugatskiy, and Boris Strugatskiy, cinematography by Aleksandr Knyazhinskiy, Georgi Rerberg, and Leonid Kalashnikov, and edit by Lyudmila Feyginova.

261 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Ivan’s Childhood, directed by Andrei Tarkovsky, screenplay by Vladimir Bogomolov, Mikhail Papava, Andrei Tarkovsky, and Andrey Konchalovskiy, cinematography by Vadim Yusov, and edit by Lyudmila Feyginova.

183 notes

·

View notes