#LAOTIAN ACTOR BASED IN THAILAND

Text

BL- BOYS' LOVE:

BBomb (PHOULUANG THONGPRASERT aka NOH) loving Jin (THANATHORN KHUANKAEW aka JOM) as if no one is watching.

And then there's him. Keam (played by SARUN BOONMONGKOL aka KONG) No matter how many times I watch this series I don't get him. He's freaking adorable. He has a girlfriend but first I thought he was crushing on Jin..but then I guess like everyone they were working with Aim to unite BBomb with Jin. Buy then there was his OBSESSION with that cutie Ball. IJDK.

#NITIMAN: THE SERIES (2021)#THAILAND#A LOOK BACK#My GIFS#BBOMB & JIN#KEAM#ENGINEER + LAWYER#BBOMB CARING FOR JIN#KEAM LOOKING ON#OVERNIGHT WITH BROS#GIFS by ME#THAI ACTOR/MODEL#LAOTIAN ACTOR BASED IN THAILAND

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

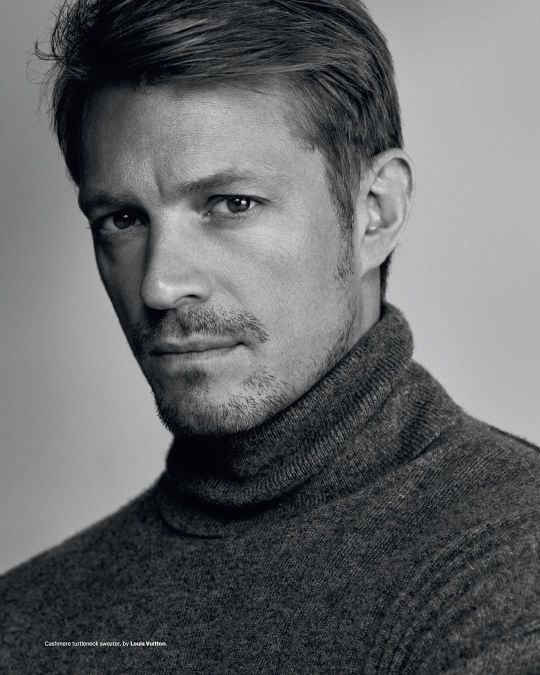

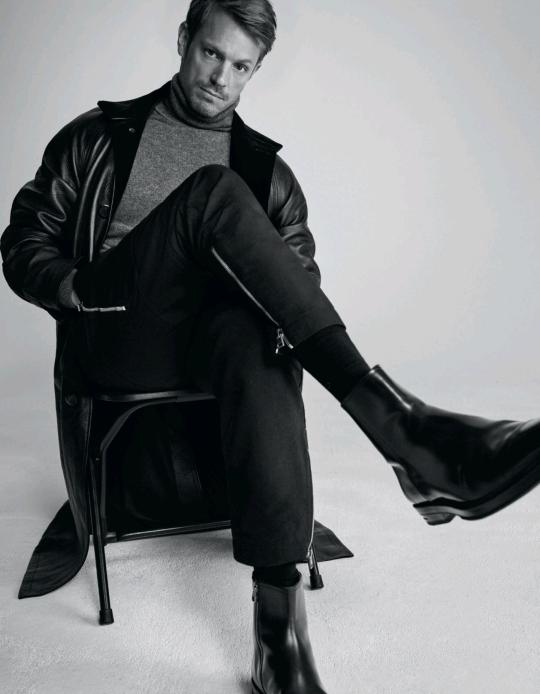

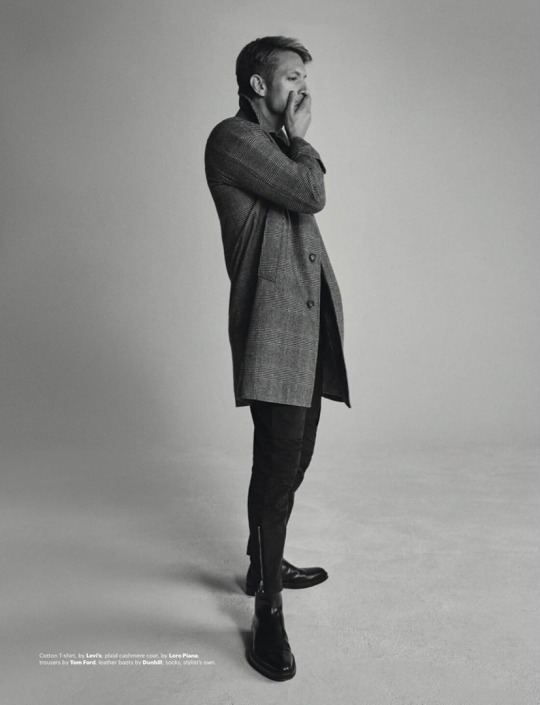

Esquire Singapore Dec 2019 - Joel Kinnaman Interview

OBSERVERVABLE ACTS

Editor-in-Chief: Norman Tan

Photography: Michael Schwartz

Stylist: Chloe Hartstein

Groomer: Kristan Serafino

Story: Wayne Cheong

Instead of a rooftop shoot that we had planned, we’re indoors at Dune Studios on Water Street. Outside, the weather is every writer’s dream: “It is an ash-streaked sky that portents a downpour.” “Like a warning, steel wool hangs overhead.” “A dishevelled blanket of grey that drifts languidly like detritus in a muddied pond.” A wet weather doth not a good shoot make.

When Joel Kinnaman arrives, the first thing you notice is how large he is. Bigger than life, broad-chested, he sometimes stands astride, like he’s about to break the spirit of a wild stallion. Then, there’s that presence; a sort of aura that’s quiet but still strong-arms you for your attention.

Just as the fashion shoot is about to start, Kinnaman asks if he could put on his own playlist for the shoot. He brings up his Spotify playlist, titled ‘For some of mankind’. ‘What Becomes of the Brokenhearted’ by Jimmy Ruffin plays.

“The playlists are just for fun,” Kinnaman tells me. “I’ve made a playlist for every project that I’ve been in.”

The project that this particular playlist was made for is For All Mankind, now playing on Apple TV+. It’s a show that puts forth the idea: what if America lost the space race to Russia?

Created and written by Ronald D Moore, the visionary behind the reimagined Battlestar Galactica and Outlander, For All Mankind stars Kinnaman as Edward Baldwin, a NASA astronaut who works alongside Buzz Aldrin (Chris Agos) and Neil Armstrong (Jeff Branson). Kinnaman’s character isn’t based on a particular historical figure, instead he is a composite or a representative of the ‘all-American’ astronauts of that era.

“I’m half-American and half-Swedish,” Kinnaman says. “I’ve lived in Sweden and America so, in a way, I’ve a split identity. My favourite part of the American spirit is not giving up. If they get knocked down, it is a national honour in getting back up and continuing the fight. In reality, when the US got to the moon, it concluded the space race. We didn’t get the continuation in space exploration that everyone was promised.”

Kinnaman is drawn to the science-fiction genre, fantasising of what could have been (though it can be said that the broad field of fiction can also put forward, ‘ what if’). Growing up, he watched the Star Wars movies, he loved the cyberpunk feel when he shot Altered Carbon. He is a fan of Blade Runner due to its dystopian future.

Do you think that sci-fi’s dystopian trope is becoming a reality? Kinnaman muses on that. “We’ve a president who is a national and international embarrassment. He’s immoral, a compulsive liar, a narcissist who doesn’t respect or appreciate democracy. I pray and hope that this nightmare would soon come to an end.

“But I believe we have the potential to overcome this. If we change paths and realign our focus in coming together as a human family, we can solve whatever problems that come our way together.”

This sentiment is echoed in For All Mankind, although the loss wasn’t the be-all and end-all for America. According to Moore, in losing the space race, America ends up the winner in the long run because of the continual effort into space exploration.

“Art can be a little lazy in pointing out the negatives. In many instances, the role that art and the artist play is showing us what’s wrong: that’s important but showcasing the positives is equally important. For All Mankind shows us how we should be operating if we are guided by our better angels.”

Physicist and theoretical biologist, Erwin Schrödinger, came up with a thought experiment. Imagine, if you will, a cat that’s sealed in a box. And inside that box is a device that might or might not kill the cat. Quantum theory states that quantum particles can exist in a superposition of states at the same time. Some even theorise that the quantum particles will collapse to a single state when it’s observed. When applied to Schrödinger’s cat, the feline is both dead and alive until you open the box.

Schrödinger came up with this thought experiment to explain that “misinterpreted simplification of quantum theory can lead to absurd results which don’t match real world quantum physics”. In the real world, it’s absurd that the cat is both dead and alive at the same time.

But one can also see this as an example of how the scientific theory works. Nobody really knows if a theory is right or wrong until it can be tested and proved. It’s like asking someone out on a date, you don’t know if that cute girl or guy will go out with you until you ask; the possibilities of rejection and acceptance remain in co-existence.

That is before you open the box.

Observe: Joel Kinnaman wouldn’t have existed if his father, Steve, had not defected from the US Army. An Indianapolis native, the elder Kinnaman was drafted and stationed in Bangkok, Thailand during the Vietnam War. While he was there, he started spending time with European backpackers, who have a different perspective of the war. A seed was planted. It finally blossomed when he attended a friend’s wedding in Laos. “It turned out that the woman’s family was half Laotian and half Vietnamese,” Kinnaman says. “It was an emotional moment for my dad. He asked himself if these were the people that he was going to kill.”

Still reeling from the love he had witnessed, the elder Kinnaman returned to his base. It was then that he was given the news that he was being reassigned to the battlefront in Vietnam.

In the history of war, the common punishment for desertion is death. According to the US Uniform Code of Military Justice, Article 85, it is meted out “by death of other such punishment as a court-martial may direct”. (Since the Civil War, only one American serviceman was executed for desertion: Private Eddie Slovik in 1945.)

Knowing the penalties for desertion, the elder Kinnaman made the decision that night to leave camp. He hitchhiked his way up into northern Thailand and into Laos. He burned his passport, changed his name and passed off as Canadian. For the next four years, he lived life among the Laotians doing odd jobs. Then, he found out that Sweden grants asylum to Vietnam deserters. Since moving to Sweden, President Jimmy Carter eventually issued an amnesty in 1977. The elder Kinnaman continues to reside in Sweden. After his first marriage ended, he was involved with Bitte, a therapist. This relationship yielded Joel.

“I’ve been working on the script about his life,” Kinnaman says. “The idea would be that I’d play my dad but I’m getting a little old.” It’s a story to be told, one about the dangers of blind patriotism; a tool that’s often exploited by governments. “We need to be critical individuals who should make up our own minds.”

Observe: Kinnaman had his first taste of acting when he was 10. He played Felix Lundström on Storstad, a soap opera that looks at the lives of the residents living in the fictional town of Malmtorget. Back then, Sweden had only two TV channels so even if it’s a secondary or even tertiary role on an ensemble piece, people will recognise you. “I didn’t understand it,” Kinnaman says. “There was something thrilling about being famous but there was something I didn’t like about it either.” His whole experience as a child actor was underwhelming.

In fact, taking a page from ‘history repeating itself ’, observe as Kinnaman could have been a soldier in the Swedish army.

“It was mandatory for the men to be conscripted for a year in the army and it was during my time when the rules for enlistment started to relax,” Kinnaman says. “If you didn’t want to enlist, all you have to do is purposely fail the proficiency tests.”

Alas, Kinnaman was so caught up in the competition that he aced it. His results showed potential to be a company leader. He was enlisted and assigned to an 18-month tour in the Arctic Circle but Kinnaman plum forgot about it. When he moved to Oslo, Norway, to be a bartender, he received a call from his mother, informing him that there was a government notice stating that he was supposed to enlist in three days.

He called the army to tell them that he was no longer in the country. “They said, this is a serious offence and I could get prison time for this. But if I were to write a letter to explain the situation, I could get out of this.” And then he forgot to write the letter. Kinnaman continued working odd jobs but he was always haunted by the thought that if he were ever to be arrested by the police for anything, they might discover his draft dodge from his records and he would be sent to prison.

“I ended up at this fight outside a night club and got taken in by the police.” Kinnaman says. Observe: Kinnaman could have ended up serving his sentence for draft dodging but nothing came of it.

Acting was calling out to him once more. His friend, Gustaf Skarsgård (famously known for his role as Floki in History Channel’s Vikings), was on track to becoming an actor and advised Kinnaman to apply for theatre school. After several applications, Kinnaman finally got into what he describes as “Sweden’s second-best acting school” and would go on to film two movies during his enrolment.

After graduation, he continued acting in Sweden before moving to America. He kept himself busy. He made an appearance in The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo; starred as Governor Will Conway in House of Cards; made people notice with his portrayal as the homicide detective, Stephen Holder; scored the lead role in the Robocop remake; was cast as Rick Flag in Suicide Squad.

The one genre that Kinnaman can’t seem to appear in is comedy. Yes, he has a stern demeanour but the man is also funny. “Sometimes, Hollywood sees you in a certain way and it’s much easier to get cast for it. And the next is similar to that and so on. I haven’t made an effort to dissuade people’s opinion. The lighter side is probably more me.”

The closest he has gotten to doing comedy is the shooting of the Suicide Squad sequel. Helmed by James Gunn, Kinnaman said in another interview that it feels like he’s “shooting his first comedy”.

“I’ve been around tough people with issues before,” Kinnaman continues. “I’ve had some bad times so those kind of environments were natural to be in. It’s a survival mechanism too. A way for me to cope as I grew up. At the time, you’re figuring out about your identity. I felt insecure, powerless and didn’t know what to do in life.

“It was a period of my life that was pretty negative. But one of the beauties of acting is that those dark periods become a mother lode that you can mine from. Maybe I’ve drawn a little bit too much from it by playing too many tough guys.”

In May 2016, Kinnaman was one of the delegates and personalities from Denmark, Norway, Iceland, Finland and Sweden who was invited to one of President Obama’s final state dinners. Kinnaman, dressed in a sharp tuxedo, attended the dinner with his then-wife, Cleo Wattenström.

He overheard that the Obamas were fans of House of Cards and was looking forward to being introduced to them. At the reception, he and the other representatives stood in a row as President Obama made his way down the line, shaking hands and posing for a photo op. By Kinnaman’s admission, his mind wandered as he imagined what he’d say when President Obama came up to him. “Maybe I’d say, ‘Mr President’, and then he’ll say ‘Governor Conway’, and then we’ll laugh. And we’ll end it with a cool handshake.”

And all of a sudden, the president stood before him and Kinnaman muttered, “Mr President…” There was an awkward pause. Kinnaman would recount that it’s very possible that either the Obamas hadn’t watched the episode that he was in or if they did, his presence made zero impact. Before the silence could prolong, Kinnaman ended with, “thanks… for everything”. President Obama said something along the lines of, “Surely but surely, we cannot lose hope” and Kinnaman was ushered off.

He would retell this story when he introduced President Obama at Brilliant Minds, a conference of creative individuals who embody the forward-thinking spirit of Sweden, in June 2019. After the introduction, he returned backstage, where President Obama was waiting for his cue to go up. “He had this huge smile on his face and he said to me, ‘bring it in for a cool handshake.’ We hugged, we talked for about five minutes. He was super friendly. I’ll always remember that moment.”

Kinnaman isn’t shy about his politics. He voiced support for the #metoo movement; he had championed the environmental cause by one of his fellow Swedes, Greta Thunberg; he does not hide his disdain for the Trump administration.

“I think the last UN report stated that we have about eight years to turn back our carbon expenditure into the atmosphere,” Kinnaman says about where we’re heading as a species. “You don’t have to be a prophet to see that the world is heading towards the wrong direction. The oceans are heating up, the glaciers are melting. These natural disasters will be more frequent and that’s gonna lead to more tensions among countries.

“Politically, we’re moving towards a more nativist direction; people are pulling away from international cooperation. There’s the rise in disinformation campaigns, which will threaten democracy.”

But Kinnaman, ever the optimist, still believes in the human spirit, that we can innovate our way out of this quagmire.

Observe: Kinnaman, who was born with pectus excavatum, chose to correct the disorder instead of living with it.

Pectus excavatum is a chest-wall deformity that affects roughly one in 400. Instead of the breastbone being flush against the chest, it sinks in. Measured on a scale called the Haller index, anything above an index of 3.2 is considered severe. Kinnaman’s index was a seven or an eight.

“It’s something that’s survivable,” Kinnaman explains. “But it’s a condition that grows worse over time: your posture becomes worse; your stamina worsens as your heart is not given room to pump. By correcting it you can add years to your life.”

For a condition this severe, doctors had to insert two curved metal bars across his chest. Then the bars are turned to force the chest out and then the bars are wired to his ribs. The operation changed his life for the better. He doesn’t feel self-conscious whenever he removes his top. Six weeks after his surgery, he had to do reshoots for Suicide Squad. It was a fight sequence but Kinnaman sucked it up. “Would you like to feel it?” He asked.

He raised his arm like an invitation. I reached out and felt the spot, where the metal bars are, beneath the fabric and skin.

That’s an interesting party trick, I say. Kinnaman could only chuckle in response.

“It’s funny, if you ask me to say a line from a movie that I’ve been in before, I can’t. Not one line from any movie that I’ve done but I once did a monologue that was one hour and 30 minutes and I knew it by heart after 10 days.”

Kinnaman used to opine that as a Swedish American, growing up with dual cultures gives him a better perspective of the world but that also left him feeling like he doesn’t belong. He jumps from place to place, leading a nomadic existence.

“But I think,” he says as though he had stumbled upon some great truth a long time back, “I don’t wanna travel so much any more. Home. That’s where I’d like to be. I have two bases: one in Venice, LA and the other, an hour outside Stockholm.

“Growing up, my family didn’t have any money. We lived in this tiny little cottage that was in the middle of the woods. Now, I have this piece of land, where my family lives. This past midsummer was the first midsummer that we all spent together.

“That’s my new happy place.”

Joel Kinnaman looks like a man who has placed the final piece in that mystery of his life. He has stopped worrying about how he’s perceived by the public. He has exorcised people who have “struggled with jealousy, who don’t have a natural inclination towards generosity”. He has zero tolerance against bullshit. He likes how his career is shaping up—aside from Suicide Squad 2, For All Mankind is now filming a second season, and Kinnaman has three films coming out: The Informer; The Sound of Philadelphia and The Secrets We Keep; the last two, he avers, are his best work. “People who have watched me for a long time, it will remind them of my early career and for people who recently followed me, they will see a new side of me.

“I have goals that I’d like to achieve. Actor awards are such bullshit… until you get one. But yeah, that would be great. In future, I’d definitely want to be in a producing role and at some point, I’d like to also direct.

“I’ve said that I’d direct in five years time for about 10 years now.” That might change. His life is still a long and open road ahead.

Schrodinger’s cat posits two states that the creature can be in—dead or alive. But what if there’s a third option. That within the confines of the box, the cat is not there. It’s escaped. Unburdened from the stipulations of a thought experiment, free to do what it wants.

#photoshoot#magazine#joel kinnaman#esquire singapore#interview#we feed on scraps of new info#ive linked his Spotify playlist for people who missed it in march

184 notes

·

View notes

Link

In the early 1960s, as the conflict in Vietnam between communist and US-backed anti-communist forces gained traction, US intelligence operatives focused their attention on Laos, Vietnam’s sleepy neighbour that, at the time, was populated by 2.2 million people. The “secret war” that was to come – an anti-communist paramilitary operation waged by the CIA with support from the Hmong ethnic minority – would see the US carry out the heaviest bombardment in history.

In A Great Place to Have a War: America in Laos and the Birth of a Military CIA, a forthcoming book to be released 24 January by Simon & Schuster, author Joshua Kurlantzick uses recently declassified records and extensive interviews with former CIA operatives to shine new light into this war and the mission behind it, known as Operation Momentum.

In A Great Place to Have a War, Kurlantzick, a senior fellow for Southeast Asia at the Council on Foreign Relations, profiles four major players in the war: the CIA operative who engineered the operation, the gregarious general who led the Hmong army in the field, the US State Department staffer who took charge of the war as it grew, and the unpredictable paramilitary specialist who trained the Hmong army – and is believed to be the inspiration for Marlon Brando’s character in Apocalypse Now.

Ahead of the book’s launch on Tuesday, Kurlantzick spoke to Southeast Asia Globe about what inspired his research, the stunning scope of the war, and how it sparked the growth of an autonomous CIA in the 21st century, one that continues to wage shadow wars around the world.

****

What prompted you to write this book and investigate the origins of the CIA? What were the most interesting things you found out?

I was based in Bangkok in the late 1990s and early 2000s as a reporter, and I travelled to Laos a lot at that time – and have since. I became fascinated by how this war had really had an enormous impact on Laos, and yet had been largely forgotten in the US, and so had been kind of part of a pattern of US foreign policy in which countries can become central to policy-making – even tiny countries like Laos – and then there is a 180-degree shift, and those countries are all but ignored. Also, I had done a fair bit of research on the early days of the CIA for one of my previous books, a biography of Jim Thompson, the famous American expatriate in Thailand and former intelligence officer. That research drew me into the early days of the CIA, and then I became fascinated with how the CIA shifted – how it shifted from a small, analytic/spying organisation into one that was much more responsible for paramilitary activities, and one that became, increasingly, one of the most important actors in US foreign policy-making.

Can you tell us a little bit about some of the major characters in this book, their significance, and how you came across them?

All four of the major characters in the book have now passed away. One of them, the former US ambassador to Laos, William Sullivan, I never met. I did, however, speak to many of his former aides and received his personal memoirs; he also wrote several published books about his diplomatic career. Sullivan played a unique role: he was the US ambassador but essentially co-managed a war along with the CIA. I met Vang Pao, the leader of the Hmong forces, about a decade ago, while researching a magazine article… and spoke with him at length about Laos and the Hmong-American community. I spoke with the other two main characters, Bill Lair and Tony Poe, at various times by phone and in person before they passed away; Bill Lair was the CIA operative who conceived of the war effort, and later was disillusioned by it as it morphed from a small-scale effort to assist the Hmong to a massive war that did not really, in his mind, put the priorities and interests of the Hmong and other Laotian anti-Communists first. Lair wound up leaving the operation as it grew in size and he became more disillusioned, and he saw it as too Washington-centred and Washington-dominated. I think he always regretted what had happened in how the war was run.

Can you explain the scope of this war – how big it was and its role within the Vietnam War?

It eventually developed into a war that consumed hundreds of thousands of anti-communist and communist Laotian troops, and lasted for nearly two decades in Laos. Given the size of Laos – it’s tiny – this was a huge war for the country. And at least early in the conflict, in the early 1960s, Laos was a high national security priority for US administrations – it was one of the main foreign policy topics of discussion in the transition period between the Kennedy and Eisenhower administrations. This might seem amazing today, since Laos has totally dropped off the US foreign policy radar, but it was true in the early 1960s. Kennedy devoted his first foreign policy-related press conference to Laos, actually. It was certainly subsumed within the Vietnam War; and, as the war went on, one of the problems was that Washington wanted to use Laos as a theatre to chew up North Vietnamese troops, but in doing so, it often chewed up Laotian anti-communist forces at a rate they could not sustain.

How did the CIA’s war in Laos pave the way for its current ‘shadow wars’ around the world?

The Laos war was really the first conflict in which the CIA (along with the US ambassador in Laos) was given such a control of a conflict – arming local forces, advising them, coordinating bombing efforts, even doing some actual fighting by CIA operatives. The conflict made the CIA a more central actor in the US foreign policy apparatus, and entrenched paramilitary work within the CIA in a way it hadn’t been before. This entrenchment never fully went away, and in the current war on terror, the CIA, along with Special Forces, plays a central role assisting foreign forces, overseeing drone strikes, conducting strikes on the ground in places from Pakistan to Somalia. And all of this is done with relatively little oversight, as happened in Laos; there is far less oversight of the CIA and Special Forces than there is of the conventional US military. This might be good, politically, for an American administration, but it’s highly problematic as a way of conducting low-level wars all over the globe.

How is Laos still dealing with the remnants of this war?

Laos is still really shattered by the remnants of the war, and will be for decades. There remains a vast amount of unexploded bombs in the country, and a significant portion of the country was disabled by the war, and the infrastructure (which was already minimal) was destroyed. The civil war split the country in many ways, and since 1975, the Laotian regime has remained a repressive, one-party state. It isn’t really a communist state, but it’s certainly one of the most repressive states in the world, even though when you visit the country, it does not seem as menacing, outwardly, as a place like North Korea or Eritrea or even Cambodia. But it is. And the war drove a high percentage of the population into exile, becoming refugees; this robbed the country of educated people, and Laos still struggles from that exodus.

#Southeast Asia#Laos#Foreign Intervention#A Great Place to Have a War: America in Laos and the Birth of a Military CIA#History#Resources

42 notes

·

View notes