#L'Affaire Danton

Text

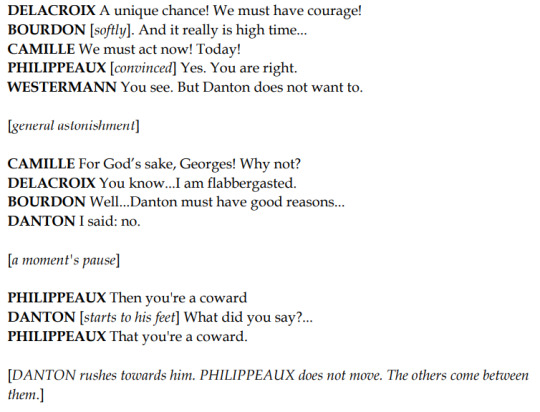

Philippeaux is the real chad here.

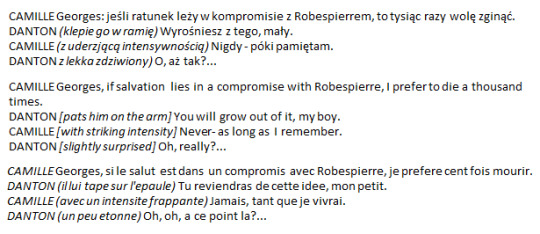

-from "The Danton Case" by Stanisława Przybyszewska

#the danton case#Stanisława Przybyszewska#Przybyszewska#frev#danton#philippeaux#desmoulins#l'affaire danton#french revolution

13 notes

·

View notes

Photo

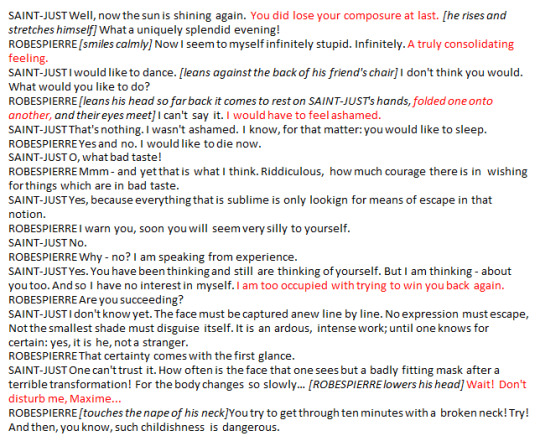

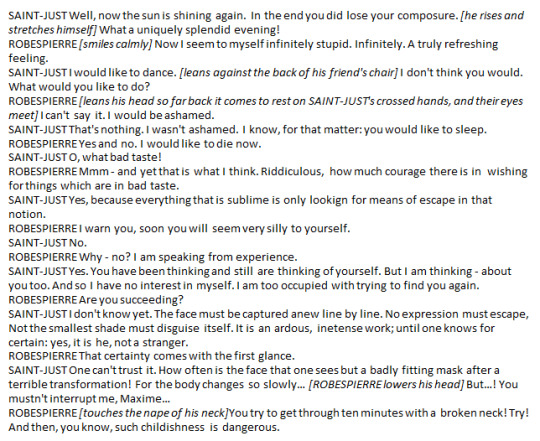

So the day has come and I will finally put my hands on one of the most beloved scenes from Thermidor.

I would like to dance scene first captures our attention by being a first clear instance of a respite after an over hour long, increasingly more intense monologuing by the Comsal. I would argue, that this is not the first one, but that one is hard to miss, as it’s soemthing which happens between the lines and more in the stage directions/actors’ expressions and is easy to miss or to not include in a staging altogether. This one is, however, refreshing and calming without any other drama going on between the phrases.

The first thing, which in my opinion makes it standout from other „nice” scenes from either The Danton Case or Thermidor is that it truly loses it grandiloquent tone. When in TDC Robespierre talks with Saint-Just or when he tries to reach out to Camille there is alway a lot at stake, and their is always some or other ulterior (not necessarily: bad) motive going on symultaneously. Here the issue had been resolved completely right before this scene – which makes it right, I think to call it a separate scene in its own right. Yes, Przybyszewska did nothing more than to divide the play in two Acts, but I think it’s mostly due to the play being unfinished; if she had sufficinet time to get back to it, I’m sure she’d put some other system in place (the room doesn’t change so perhpas she left it as a continous streams of „scenes” rather than divide it, as to not break the unity of place? Mayhaps, but I still think the division is visible and barely seamless).

First of all, I’d like to point out, that while all in all I do like Bolewsław Taborski’s translation of this scene (I have it memorized and it really flows from the tongue very well when spoken), there are few points in which I would have made small changes (marked red). This is becase sometimes the meaning of the whole phrase lies in either this or that word, and the difference is small in size, but absolutely crucial.

· You did lose your composure at last. vs In the end you did lose your composure.

Here it is more important that Robespierre’s tensions boiled in him, and that Saint-Just egged him on to the point of an outburst than the outburst had happened at the end of something. It shows us that these emotional turmoils do exists in Robespierre and torment him as much as they do any other man, but that he doesn’t let it show on his face, unless he’s being pressured by someone who knows what to say exactly and which buttons to press to achieve the goal. It also workes much better in conveying a supposedly smug expression on Saint-Just’s face, a tone which we can assume is triumphant, while Taborski’s phrase make it look more like a calm recounting. Here it begins to unfold in front of us that Saint-Just isn’t immovable, that he is in fact quite an easy going person when faced by no one else but the person who knows him most closely and intimately.

· A truly consolidating feeling. vs A truly refreshing feeling.

I admit that this one is mostly a personal choice, becasue in a dicctionary, pokrzepić is, in fact to refresh. But as a native speaker I just know that pokrzepić is less ethreal, it’s in a fact a very grounding, calm and solid word. It works as a contrast between the increasingly playful vocabulary Saint-Just presents and the still calm and more cautios about displaying emotions Robespierre. This is a tiny detail working as a characterisation.

· Hands folded one onto another vs crossed hands

This one, in turn, seems to me to be pivotal. Hands which are crossed send a message of denial, anger, refusal and so on. Hands folded onto one another are more about being calm and at ease, and about acceptance. This can still be resolved through proper stage movements, but I’ve yet to see it done properly (HERE I talk about why the hand folding and head leaning back is extremely important).

· I would have to feel ashamed. vs I would be ashamed.

The difference is small, but striking. You feel ashamed out of your own volition (even if it’s influenced by the environment), but if you have to feel ashamed, does it not mean that you don’t necessarily see the need for shame, but that your environment does and is forcing you into this emotion? That’s the way I see it and in my opinion it subtly kets us know that while Robespierre, for one, sees nothing wrong with the situation currently unflding between the two, he knows it would not be met with proper understanding from other people. I may be reading too much into it, but I would have to see the German original.

· I am too occupied with trying to win you back again. vs I am too occupied with trying to find you again.

So this allows us a glimpse into the untold life behind the curtain that Robespierre and Saint-Just have – and share. Zdobyć literally means to win, i’s something you could say about a prize. Finding (even finding agains) doesn’t have the same air of grandeur about it, finding may be accidental, winning, however – is something achieved through a sense of purpose. We now see in its entirety that Saint-Just isn’t taking any of this lightly, no matter his smile or his playful expressions. He has won Robespierre in the past, and then he’s lost him, and now he is adamant to win him back again. This is no small thing – this is his life purpose, his prize.

· Wait! Don’t disturb me, Maxime... vs But...! You mustn’t interrupt me, Maxime...

Here the difference is again pretty optional, but I like the personal feeling my version evokes, the familiarity/intimacy. By removing mustn’t we remove the tone of an order, something which is cold and distant. Yes, Saint-Just is disappointed in Robespierre’s reaction (even though, if you had read the post I had referenced, it is completely understandable), but that doesn’t mean it offends him in any way, therefore there is no need to assume a cold pose.

Now, with verbal details out of the way, I would like to focus on the tone of the scene as a whole.

When I talk about intimacy, I’m being very serious and straightforward. While I am the last person to make everything about sex and even rarely see things in a sexual context, here I had never any doubts that Maxime and Antoine spoke in code – if we can even say it was a code, for it was all so plain.

First of all, I’m not even talking about the „you would like to sleep” bit, because while it didn’t call for a separate bullet point on my list, the expression that was used in Polish was rather „to fall asleep”, without any sexual innuendos. This is the familiarity at work, not intimacy, it is a reference to Robespierre enormous tiredness, one of which Saint-Just was all too often a witness to. Antoine’s heart and mind ar at ease at the moment,s so he would like to extend this calmness to Maxime and offer him – even though he knows it will more than likely be refuted – some of this relaxation, too. What he doesn’t expect, I think, is that Maxime takes him up on that offer but with a twist, and turns a conversation which could have remained friendly into something from an another, flirty level.

I’m assuming that everyone and their mother already knows this, but la petite mort is an expression used in French to describe an orgasm/a feeling after an orgasm. I’m not saying that by saying that he would like to die now Maxime is making a direct request/offer, but he sure is making a clear enough reference – which is why I always imagined Saint-Just’s reply to be said with laughter rather than completely seriously. Not to mention, the rest of this exchange makes another dig at it: I will argue that „a sublime thing looking for means of escape” is another sex reference, or at the very least could be read that way. This is of course too much for Maxime, whose prudish nature in this regard was already explored at depth in The Last Nights of Ventose.

The last thing I would like to talk about is a small, internal reference which I think this scene is making:

When at the end Maxime complains about trying to get through the conversation with „a broken neck” I think it serves (even if inadverently) two purposes. One is, of course, to cut the conversation short and get to the bottom of the political intrigue, which is what is more pressing and interesting to him than any flirting could ever be. The second, however, brings to my memory the scene at the end of The Danton Case, where Saint-Just tells Robespierre that he has broken his spine.

ROBESPIERRE [His legs give way under him. He sits at the edge of his bed.] Oh, you have finished me, you know.

SAINT-JUST [leaves the table, walks aimlessly] And you have broken my back.

In the original he actually says: And you havebroken my spine. A spine is, of course, an extension of the neck in terms of anatomical built, and so I believe these two instances should be compared side by side. It is very telling (though I may not yet know what it is exactly they are saying) that Robespierre metaphorically breaks Saint-Just’s spine when they are fighting, but Antoine, in turn, (a bit less) metaphorically breaks his neck when they are makin up. Is this a foreshadowing, that no matter what they are doing and no matter the turn their conversation is taking, they are doomed?

#Christ has risen - indeed He has risen.#Happy Easter everybody!#frev#french revolution#the danton case#sprawa dantona#l'affaire danton#thermidor#Stanisława Przybyszewska#stanislawa przybyszewska#antoine saint just#maximilien robespierre#maksymilian robespierre#rewolucja francuska

36 notes

·

View notes

Note

C'est un exercice bizarre mais fascinant d'un fan polonais, je crois. Originalement la pièce de Przybyszewska, réimaginé par Jan Klata, c'est-à-dire version beaucoup plus 'queer' - et ensuite, l'addition de la musique pour youtube. (Je vous en prie de m'excuser mes erreurs de langue.)

Ah, je crois comprendre, merci. C'est assez bizarre, en effet.

#Stanislawa Przybyszewska#L'affaire Danton#Jan Klata#Robespierre#Maximilien Robespierre#Camille Desmoulins#Révolution française

1 note

·

View note

Text

Generally speaking, there is no (good?) classic piece of literature, where one cannot spot, or at the very least attempt to prove that it is possible to spot, a biblical reference. And it is no different with Przybyszewska.

First of all, I want to underline that with her it is not a mere coincidence, but a very much conscious decision. She was not religious, but obviously grew up in a culture permeated with christianity, and for a period of time even lived through the help of Ministry of Religious Affairs and Public Education; it doesn't mean that she was chosen for her great impact on religious affairs, but that for the people of the Second Republic the knot between enlightment and religion was closely tied. And Przybyszewska, while a visionary in her own field, was very much a person of her times.

I also want to preface the post with saying I will be using the King James translation of the English Bible and Biblia Tysiąclecia of the Polish one when necessary. It is also in no way my intention to draw any religious conclusions or to dwelve in any way onto religion – which by the way I hold sacred, so please treat this with respect.

The most prominent – if not the only one fo – groups of biblical references in the two plays is having Robespierre depicted in such a way it is impossible not to think of a Christ immediately. His deification is something even more than a part of the text, it's Przybyszewska's innermost feelings and thoughts influencing her works in the most visible way. That's way there's so much of it, and why it's so consisntent.

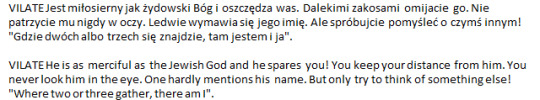

First of all, there is the thing – discussed at length mostly in Thermidor - that Robespierre is percieved by everybody coming into contact with him to be omnipresent and omnipotent. He is not a mere human, but some timeless being, all-knowing and all-powerful. This is tackled on two fronts: positive and negative, positive being done mostly by Saint-Just, who has the unwavering faiht in Maxime, and whom Maxime even calls an Apostle on one occasion (that is: the forefront followerr); Camille dabbles in having "faith" in Robespierre as well, though I'd say this is mostly depicted in The Last Nights of Ventose(more about that later, because oh boy), while Eleonore, strangely, perceives him mostly through the humane lenses? His political opponents, on the other hand, jump of fright every time someone mentions his name, or even every time a door opens when they are conspiring against him, and what they think about him is equally interesting, for they all agree, more or less emphatically, that he truly is irroproachable. They perceive him in a way one would percieve a suparnatural creature. Vilate sums it up quite nicely, albeit his personal opinion was slightly augmented in comparison with the rest of his colleagues (because of his past as a priest, perhaps? He even says at one point that he deified Robespierre and prayed to him):

And the talk about him at the beggining of Thermidor is not deprived of some vocabulary, slipped here and there, that is connected directly with christian rituals: rising altars and comparing an altar to a throne. Billaud (who understands Robespierre far batter than any other character of the play, with an excpetion perhaps being made to Saint-Just) makes a curios analogy – he says that Robespierre is a creator, but a sterile one, whose creations lack life. While the trademark of God is that He breathed life into humans, thus gifting them with living and all its implications.

Robespierre is thus called a faulty God, something more than a human, but not quite God; and even as a seraph he is not without imperfections. The explanation as to why is that is twofold: either because he is too human (as Fouché tries to paint him out to be, talking excessively about his weak health, his supposed tuberculosis and prideful timidity) or because what he reigns over is not quite Heaven and Earth – but Hell (as Billaud puts it without beating around the bush).

There is also quite a more frank and obvious allusion to Robespierre's adoptive divinity. Billaud in his famous rant says that Robespierre has ventured into the land of self-deification, and that he considers himself to be a holy monstrance – for those of you not familiar, a monstrace is a richly decorated, usually gold liturgic vessel, used to exhibit the holy Host. There could be no clearer way of saying that Robespierre considers himself to be a God and is acting accordingly. That Saint-Just is in one breath called a "hot-headed youth", who desires to conquer the world for the one whom he loves (the Polish translation is in this regard so much more beautiful than the English one, which is quite frankly a lackluster) is just a further proof, as God's existence secured the existence of martyrs and saints, spiritually conquering the world for His love. Another thing is how Robespierre affects those around him, then, and here Billaud uses a great word in Polish, which English "thunderstruck" does no justice: Lecz jesteśmy porażeni. But we are paralyzed, only "paralyzed" expressed in a highly biblical language, a word which means something more spiritual in origina than mere physical paralysis. For example Jacob became "porażony" when he was struck by God, but I could find various other expamles as well.

In The Danton Case there is – obviously – fewer references like that, but Lucile makes one very good when she talks with Maxime face to face.

What she says I see as a clear refernece to Jesus Christ. Miraculously sent by God to help, has undergone a change which strips him of one part of his identity(the all-powerful Robespierre – Christ – has replaced humane Maximilien – Jesus), leaving only the second one, as a lot of people thinks that when Jesus resurrected, He came back only as a God, forgetting He came back as a man too; it's a common mistake – not to mention Robespierre corrects her, therefore: he did retain both his identities, though one seems to be overshadowed by the other. Why, oh why the French translation decided to go into an entirely different direction here? (We of course know why, to ground it further into historical reality, by making the readers aware of the fact that Robespierre was physically short; Roland Barthes would have something to say on the topic and maybe i will, too, one day.) It completely erases the religious connection she drew, in my opinion. It's still there, to an extent, thanks to the "God Himself must have sent you...", but this is just an everyday biblical reference, so to speak.

There are numerous, numerous things tying Robespierre to Jesus, one of which is his betrayal by friends. Have you noticed he never, never referes to his colleagues by anything more impersonal than "a collaegue"? And most of the time he calls them "friends", which holds a certain dose of affection even if it's used in a sarcastic way. He never calls them his enemies. So his "friends" betray him, much like Judas was one of Jesus's chosen few, someone from his close circle.

Another thing is perhaps more subtle on the textual level, but very telling in subtext. In his anti-capitalist rant in Thermidor, Robespierre slips in more or less visibly a ton of terms and references to the Bible, which the English transaltion ommitted (that is to say, translated in sucha way they lost their religious heritage): that capital is the new god, and the Republic is its Betlehem, and there will be people from all walks of life (shpeherds and kings) devouting their lives to it. That it's not simply a false god, "bożek", but a "bożyszcze" – a deity, but in a negative and artificial way. That it is a Moloch, a foreign deity mentioned in the Book of Leviticus, which was famously offered child sacrifices. And that it will have its own martyrs. The whole of his speech, too, has an apocalyptic ring to it, a calling for repentance of turning from the evil way they're standing on of sorts. Robespierre is a prophet, if he's not a god. (It is worth mentioning that in one of her prose works Przybyszewska's first person narrator straiht up calls Robespierre "the saint Paul of the Revolution" – a saint and a zealot who didn't experience Christ personally, but was not less devouted because of it).

Not everybody has read The Last Nights of Ventose, but there is a small scene in there, where Robespierre, trying to win Camille over, tells him he may kiss him, if he likes, if all that he needs to come over his senses is to kiss Maxime senseless, he may as well do it and be done with it.

(The sculpture is Corpus by Bernini.)

So I have the feeling I might be exaggerating this, but this one phrase always brought forth in my mind the Passion imagery, Christ on a Cross (or at the very, very least, it should remind us of the spiritual ecstasy imagery – look up The Ecstasy of Saint Therese by the same artist), and it's not only about the image, it's about the mentality behind it as well. Robespierre doesn't do it, because he is secretly in love with Camille or anything like it, he is firmly opposed to the concept of physical love – but he's fine with sacrificing his celibacy if that's what it takes to save Camille. For me it's a mirroring of the greatest sacrifice for humankind.

When he's not being deified, Robespierre is being fashioned into a martyr, and there are several clues for that. At the end of The Danton Case, for example, in Act IV, Scene 4 it is revealed he was abstaining from food and drink; albeit unconsciously, it nonetheless leaves a trace of a holy fast in the readers. He is going through his greatest trial, and his body prepares accordingly. What he tells Eleonore lets us know that he also feels responsible – for everything and everybody. That is more still than being a martyr conceals, for me that is in the territory of being a god. And I'd like to reach over to Wajda's Danton and use the imagery he used, in a similar moment, when Maxime is at his lowest. He is depicted as something even less than a dying man, but a corpse already, completely enshrouded – a corpse coming back to life once Saint-Just (the Archangel of Terror) brings him the good news about the trial and execution. And I don't have to remind you, Whose most famous trait is the resurrection.

The last thing I'd like to talk about is the scene I had already devouted a lot of thought in this post, namely the quasi-confrontation scene between Danton and Robespierre (but I have to prafec it by saying I, sadly, wasn't the one who first made the connection I am about to make, but Kazimiera Ingdahl beat me to it). If we establish that Robespierre is a stand-in for God in these plays, we also can safely assume that his negative double, Danton, is a stand-in for the opposite being: Satan. And there is an uncanny parallel between the scene in Act II, Scene 3 and the Gospel according to Matthew, Chapter 4, versets 1-11.

This cannot be a one-to-one analogy, for obvious reasons, but there is this similarity between offering an everything, which isn't yours, to a being infinitely higher than yourself, whom you both fear and perceive as someone to be adored. In tempting Robespierre, Danton also (altough probably without realisng it) tries to persuade him into giving up on life, because for Maxime to betray the Republic equals death. Please notice as well how Danton seems to honestly adress Robespierre here as someone who is not fully human: you have no human feelings, you don't even know what human feelings are (taht;s what he says in Polish; in French, for some unfathomable reason, Daniel Beauvois watered it down to "ignoring" the feelings, that is: having them, but paying them no attention, thus humanizing Robespierre even in Danton's eyes).

This now concludes my analysis. I feel sorry that it was more of an enumaration of references I spotted than a deep dive into them, but upon looking closer at them I came to a conclusion they are all focused on the one element: Robespierre's deification. There isn't that much to be said about it, then, the topic is easy (Przybyszewska accepts no contradictions to her feelings, she wants us all to see Robespierre through her admiration tinted glasses). But I hope it encourages everybody to look for references such as these in their own favourite texts. And, as always, I would just love to hear others' thoughts about it!

#I honestly think I hyped this post too much because it turns out I wasn't able to present this#(undoubtedly very inetresting topic)#in a very inetersting way :/#also please: if you have anything to say about Bible or christianity make sure it's respectful. PLEASE.#stanislawa przybyszewska#stanisława przybyszewska#the danton case#sprawa dantona#maximilien robespierre#literary analysis#l'affaire danton#maksymilian robespierre#frev#jerzy danton#georges danton#Bible#christianity#biblical references

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

What I haven't done in a very long time is a good old scene analysis and nitpicking at translation choices, which is why, after an overdue rewatch, I'm gonna look into this short passage here.

"Na granicy" means "on the frontier" in its more literal sense, but also "barely" in its more metaphorical one. Which is why I don't buy into the choice Bolesław Taborski made and will forver be angry with him for it. He strippped Saint-Just from an important layer of defense and of his own, hurt feelings in writing what he wrote. What I'd much rather see is:

ROBESPIERRE Everything alright?

SAINT-JUST Barely so.

Of course, one won't retain the play on words, but it is lost to us either way - and it's a shame, 'cause playing on words gives us yet another glimpse into Saint-Just's soul. He's just been tried almost too cruelly by his enemies, his heart has barely survived the torture of thinking Maximilien had betrayed him. This is fine, he's strong, he's fearless, he's "the favourite of the gods" and will survive anything. But there is still a bitter taste n his mouth, for he understands and recognizes than while Robespierre had not, in fact, betrayed him just yet, he might as well do it soon, this is not such an impossibility as one could think.

Playing on words is sort of snapping. He is doing his best to remain polite and unmoved in the way he's greeting Robespierre, mostly because they are being observed by enemies, but he allows himself this small menace, like pricking a skin of someone who (though inadvertently) wronged him, because he cannot do anything worse than that. This is both being wary of the person whom he has just started suspecting and giving a cold shoulder to someone to whome he was riding day and night from the military camp (didn't even stop to change from the muddled clothes). Speaking only about the frontier could be read in a similar way - he's deflecting, he's purposefully talking about more technical matters - but it would be a stretch, in my opinion.

I just so, so wish it was translated in a better way! It fleshes Saint-Just's character out, gives him more depth than a mouthpiece he becomes in various adaptations. "My" version of this line is giving an information about the frontier, being mean, trying to remain in control of his own reactions and reassuring himself for the moment. Oh, and also signalling to Maxime just under the radar that something is colossaly notalright. All at once.

Thank you for humoring me on this fine evening, this line bugged me for a while. Next in line we will have "Women and female sexuality", and then onto a new series of posts which is yet forming in my brain, but whose colective title I can now reveal to be "Noli me tangere!".

#admittedly more COULD be said about SJ's feelings at this moment but i don't want to whip the foam too much#let us leave somethig for the upcoming series#stanisława przybyszewska#stanislawa przybyszewska#maximilien robespierre#literary analysis#frev#maksymilian robespierre#sprawa dantona#the danton case#l'affaire danton#thermidor#antoine saint just

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

I promise everybody this blog isn't dead, I simply have a lot of work to do.

But, having Easter break in mind, which of the following ideas would you be most interested in reading?

The first part of Noli me tangere!, which is about Robespierre's relationship with others. The "other" in question is still debatable, but I had Eleonore in mind.

An analysis of the ending of Robespierre's and Camille's fall out ("not one word too many").

An analysis of the "I would like to dance" scene.

A comparison between Saint-Just's and Robespierre's argument in The Danton Case and their making up again in Thermidor.

#if you speak out your mind on this it will sway me in the direction because i truly have so little time now but the ideas are still there#frev#stanisława przybyszewska#stanislawa przybyszewska#the danton case#sprawa dantona#l'affaire danton#antoine saint just#maksymilian robespierre#maximilien robespierre#probably deleting this once I post but for now i'm tentatively looking for a place to start

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

After @vperyod93's great analysis I couldn't resist making a separate post just to ponder extensively over Fabre's line and what it means when faced with the whole of the play.

We don't see much of Fabre, and cannot treat it as his own thought – he's just there as a part of the The Danton Case's choir, much like in the ancient greek theatre there was one, commenting on the actions of the main heroes. Such is the role of the two camps: the dantonists and the Committee, both offering additional information and commentary, weighing in on how we percieve their main figures.

Fabre in particular hits the nail on the head with his ironic summary of what has transpired. Some of what he says could be ascribed to bitterness – a last quip of an almost dead man – but it underlines the line of action Danton took. Because while we as the readers in our reality know fully well that Danton's actions must eventually take a wrong turn, we as a voiceless, fleshless beings observing the play's universum could potentially anticipate a better move on his part (I meant to say that we read it with a bias, like a historical knowledge, or simply because the title The Danton Case is very telling, but if we take the story completely at face value, it doesn't have to be final and tragic for Danton). He is after all portrayed as a good politician, and while it's not explored, it is also clearly more than a hollow assumption, since he was initially able to fool Robespierre into respecting his unique position. And yet time and time again he refuses to either help himself and his accomplices by many possible means presented to him, or at the very least acknowledge the hard truth that he's lost. He does it, to a degree, in his very last scene, but that's not enough, someone truly well versed in politics would understand much sooner that one will always lose when faced with an opponent who has the whole governemnt and all its tools at his disposal. Those two views we get of him as readers completely clash with one another and when one rules out Przybyszewska's incompetence as a playwright as a possible reason for it (as I will always do), the only acceptable explanation is that he did acknowledge his loss much sooner than we realized, but has decided to go on for the theatrics and for the beauty of it.

I hope that by now I have managed to convince everybody Danton – while impulsive – is hardly an emotional man, but more of a calculating type. And up to a certain point I think he truly did believe not even that a rescue is available and possible, but thet he needs no rescue. The certain point I'm talking about is, more specifically, Act III, Scene 2, and it's just few lines in a middle of it:

As you may see, the English translation didn't fully embody the state Danton is in. The original states clearly: he's scatteringeverywhere like grains of sand, he's meltingonto the floor, his hat is weighinghim down. That is: he is compeltely, fully finished.

If we were watching the play normally in a theatre, it is quite possible this could not go unnoticed, because it has a potential to be stretched out in time, underlined by lighting or music, made significant through other means possible in a realm of visual arts. As it is in a book, it's easy to almost skip past it, as it is bordered by two strong conversations: Danton's fallout with Delacroix and Danton's aggresive and manipulative treatment of Camille – which is another proof that thisis the moment Danton realises how bad his position is in its entirety.

If it weren't so, he wouldn't have pulled Camille alongside to their deaths. Whatever else they thought about him, both Robespierre and Danton agreed that Camille's writing is invaluable and Danton would not part lightly with such a weapon, not under any circumstances, unless he was sure of the tragic turn everything was going to take.

The whole conversation with Camille in Act III is a superb representation of Danton's abilities as a manipulator. I think this is – in his own mind – his last show (he's not thinking, or at least not thinking in any decisive terms, about his futura defense speech), his "going out with a bang". In one word: theatricality. He could go silently, but it's not as beautiful, not as grand, as taking with him everybody who loved him and believed in him. For: if you lose, what was the point? And as aesthetics continues to teach us, "the beauty of it" might be an answer not just in art, but in life as a whole.

Let's examine the conversation Danton and Camille engage in (I reccomend reading the scene beforehand, as quoting it whole here would be too space-consuming). First of all, Danton sets the tone of it in no uncertain terms, and I quite like both the French and English translation in this regard: Vas-y, fais ton numero. All right, you can perform now. Because it will be a performance, but not Camille's – Danton's. (In the original he used a phrase which has the same memaning, but only as one of many, instead of the main one, so it's really less telling on the textual level.) All in all, he also sets the tone by being unnecessarily crude to Camille, who is very visibly upset, and for a good reason. But to Danton, this is only a foundation for mockery. He mocks Camille's speech, his intellect, his character, his felings for Robespierre.

Then the tone shifts somewhat for a short moment. Because if Camille went to Robespierre by himself, it changes a lot; on the one hand, his sudden decisiveness could be an obstacle in ruining him, but on the other hand, Danton sees this as an honorable opening. If Camille took a step such as this one on his own, Danton could let him go. He could let him be free, if he knew Camille was taken care of. Everything in this short moment screams to the audience that Danton still has some small glimpse of humanity left in him, though he already is a man so broken he relies on instincts only out of habit, whose willpower has left him. The body language of the two also signifies a sudden shift in their demeanour, as for once Camille is the one leaning towards Danton, who responds by leaning back. This is the opposite of what is commonly associated with them. But then they return to their normal ways, Camille's naivety pulling Danton out of the daze. And that is another opening, but this time for ruining Camille way more than what was possible before.

As improbable as it sounds, Camille had no idea Robespierre loved him when they spoke (just minutes - ? – before this scene). It is clearly visible to the audience, but not to him, and he only learns of this sudden and all in all good news through Danton, who – apparently – was well aware of the fact for a long time, but who up until now didn't think it prudent to tell Camille, as it could sway him in the wrong direction. He tells him now, becuase it became a useful information, a way to pretend he cares for Camille's wellbeing, while symultaneously depriving him of any real chance of a rescue, and burning his bridges all in one sweep. Now can Danton truly showcase his talent at manipulating people: his voice changes hues almost in every sentece, the many ellipses in the text indicate he talks deliberately and slowly, he is carefully reading Camille to obtain the best results. He's coaxing him, he's telling him harsh truths, he's in full control of the conversation – whenever Camille tries to take action by himself, Danton is already there, with a handy comeback, which forces Camille to reconsider. He acts as the sole keeper of the truth, which is most visible when he responds to Camille's plan of asking for Robespierre's forgiveness with a sentece: He will never forgive you. Says who? Says Danton.

At the end of the conversation, Danton voicelessly laughs after Camille's departure. His eyes however, we are told, are sad. The conversation ended exactly how he wanted it to, but he's no happier for it. Throwing a jewel into the sea might be beautiful, but it will never be joyous. What he did just now what also more than mere waste – it was a bloody offering (as the polish word ofiara means a sacrifice, an offering and a vicitm, it seems to be entirely fitting into this theory).

Now we circle back to the begging. The thread linking the jewel, Danton and Robespierre in my opinion is Camille, or rather the way the other two see him and treat him. Becuase the symbolism there is quite easy to spot: Camille resmebles a jewel in being easy on the eyes, pleasant to be around and innocuos as well as invaluable in his own right. And just as a jewel becomes an ornament to the person wearing it, he became an ornament ot his more powerful friends. The difference between them is of course: Danton throws this jewel out willingly and with a vicious joy, simply to spite others (if he cannot have what he wants, no one else will either). He will justify his actions to some degree, but I don't think he fully believes in these justifications (does he really think he's doing Camille a favour by leading him to a guillotine? I don't think so. The only honesty there is, is that for once he voices the depth of disdain he hoards for Camille). Robespierre is a complete oppiste of it, and we even have a proof – because he has already los Camille once, to Danton. And yet he defended him, in Saint-Just's words: to the point of causing a scandal. Robespierre not only doesn't throw the jewel out, but tries to catch it mid-air and restore. That it doesn't work, is not fully (though it is partially) his fault.

The more general understanding of Fabre's line, namely that it simply describes the characters of Danton and Robespierre as a whole, not just in appliance to their treatment of Camille, at the end of the day comes back to the same thing – pride and a sense of possesing. Danton is too proud to lose, and therefore when it does come to his losing everything, he will make sure it truly is everything. In his own words, he bows to no one whom he considers a lesser-than. Meanwhile, Robespierre (who does consider Danton to be a fool and overall a bad fit in the government) is willing to fall at Danton's feet if it were necessary for the Republic. There isn't much beauty in doing so, which goes to show he doesn't care for it, only for the result. This is partially why he failed at saving Camille, who needed this beauty to accept the olive branch he was being offered, and who could not accept it as it were, bare and cold. Beauty will save the world, though it isn't necessarily what Dostoyevsky had in mind. Robespierre, however, is so thoroughly deprived of the sense of beauty it becomes his undoing, as it is – by proxy – Camille's.

#as always i encourage everybody to share their thoughts on the topic#i would love to read them#stanisława przybyszewska#stanislawa przybyszewska#sprawa dantona#maximilien robespierre#the danton case#literary analysis#camille desmoulins#frev#l'affaire danton#maksymilian robespierre#jerzy danton#kamil desmoulins

9 notes

·

View notes

Photo

For a very long time I could not understand the exact, and most important detail in this scene. Antoine is at the very moment of snapping, it's nearly a point of no return for him - if he cannot persuade Maxime to assume resposnsibility for the whole of nation, state, government etc. - which we see he is unable to do - there will be nothing left for him to do. For in "The Danton Case" we don't see him as a brilliant politician all in his own glory, no, we are only given glimpses of him (though so very poignant they are) as an extension to Maxime, his accomplice, acolyte, partner, what-have-you. He is sketched before our eyes very accurately (maybe not accurately when takling about his historical counterpart, but he is very well fleshed out as a a character in the play), but only as an addition to his more brilliant half. Therefore, if Maxime refuses to act, refuses to acknowledge the resposibility lying ahead of him, Antoine has little left to do - plus, his as of yet unwavering faith in Maxime has just been brutally trampled by his very idol.

He is - and this is probably very accurate even in the context of the original, historical unfolding of the events - angry with Maxime. Angry, yet powerless. And all he can do is snap at the person he presumably loves most in the world, and tells him nonchalantly, but clearly (that is: in the cruelest way possible, in such a way that leaves nothing to imagination, which cannot be ascribed to some misunderstanding of intentions) to kill himself. The exact phrase he uses in the original is almost vulgar, too, which makes for a very stark contrast between what he says and his usual behavior. He is using coarse language and colloquial words, so that we, the audience, know something is up.

It would be very easy to assume that at this point he doesn't want to be around Maxime - why should he? At least for the moment it seems they no longer have anything in common, and one is hurt by the other - even if it doesn't seem to affet Robespierre. And that is what's worrying Antoine.

One doesn't need to be a genius to figure out that he was either crying or on the verge of tears right after he told Maxime to shoot himself. His posture (turned away to the window), his face (hidden), his voice (hoarse, which it was not before - so the tears must have been the reason for it) all give it away rather easily. It is all very understanadable, too. I think he cried out of powerlessness, despair for the future of France, their respective futures with Maxime, his life with Maxime even, since they are driving away from each other so fundamentally. So he doesn't leave the room right away, because his emotions take the better of him, and he needs a moment to compose himself, crying almost in plain sight, and yet not in plain sight, since Maxime seems to be utterly unaware of his surroundings. Which is what makes for this sudden realisation once he speaks to Antoine his last words.

You see, in the original he doesn't say 'Goodbye', altough I do think 'Goodbye' conveys the same emotions, tone and intentions as the original (and correct me if I'm wrong, but 'Salut' in French is nowhere near as poignant and heavy in meaning). He says: Be well. What is so special about this?

It's more than mere valediction, it has some final note in it, which is why I think Antoine could only understand it one way: that Maxime was actually going to kill himself. Because in what way can he see it? Robespierre has just been through a huge turmoil, both personal and public, his health is frail, his mind is on the verge of despair so great it can easily be mistaken for madness, he has just witnessed the execution of his closest, most beloved friend/partner (and Antoine doesn't delude himself, losing Camille would always be the worst thing in the world for Robespierre, worse by a lot than losing Antoine ever would amount to - the why I will analyze some other time), whom he had to sentence to death himself, and just now he was told, by his yet another most beloved person to shoot himself and he doesn't refute this in any manner, he agrees. And then he bids Antoine farewell, choosing deliberately (remeber - Maxime is suddenly very calm and sensible) the exact words that can carry a double meaning. He is not saying a farewell just for the day, but for ever.

You see, I never understood, why Antoine turnes away sharply and with suspiscion. Sharpness is excusable, but obstinate ignoring of his friend would be more in character at this moment. Suspiscion, though - there has to be a reason for it, and I think this is it. Antoine suspects Maxime will… if not shoot himself, then at the very least slit his wrists once he's left alone.

Which is why he would not be left alone. Antoine doesn't leave, even when he's not crying, even when Robespierre has said his goodbyes and as much as ordered him to leave the room. What was there left to do for Antoine anyway? Before Barrere's unexpected visit, it seemed all he could do was to brood by himself, in another man's room, maybe watching his friend fall asleep, but being so angry with said friend he wished him dead a moment ago. It made no sense Antoine, who is otherwise characterised as an active person (moving around a lot, speaking in harsh tones and quick to pass his judgement) would not storm out of the room the very moment he saw his efforst were absolutely in vain.

Unless, of course, he loved the person who was in the room with him.

#sprawa dantona#the danton case#l'affaire danton#stanisława przybyszewska#stanislawa przybyszewska#antoine saint just#maximilien robespierre#robespierre#french revolution#frev#literary analysis

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

I would like to present (extremely briefly; it's more of an invitation to their thoughts rather than anything else) two approaches that touch on a creative technique used by Przybyszewska, which has been spotted by some of her scholars, albeit each in its own way. Ewa Graczyk maintains that Przybyszewska did not write a historical drama in any way, but rather described a completely different reality, an universum in which the same events happen, but which doesn't take place on Earth, with us in it. She describes, then, something which I call The French Revolution', taking after mathematics' nomenclature. Kazimiera Ingdahl, on the other hand, spots traces of gnostic and manichean ideologies in Przybyszewska's writing, which, as we all know, are based solidly on the contrast between Heaven and Hell, knowledge and numbness, soul and mind. I mention them here solely to point out there is a dualism in her works, it is important and easily recognizable.

I have nowhere near the amount of erudition these scholars do, so I will constrict myself to some more visible matters. In my previous post about Antoine, I've made a remark that stuck with me for far longer than I had expected, and so I decided to elaborate on it.

The passage I'm talking about is this: because it could potentially reveal Saint-Just as another Danton-like minded individual, looking for power for himself through sacrifices of others. I want to explore whether Przybyszewska really did construct both of them alike?

To me it appears very probable, as crazy as it sounds. First of all, ALL of the personages are created in some reference to Robespierre. He is the only singular, original mind amongst them all, not to mentoin an axis around which other revolve, and so all of them, whether we like it or not, are somewhat similar to each other. Second of all, she clearly went in the direction of mirroring certain scenes, ideas, expressions (which I personally love to track down and compare them later), and it's exactly the same when talking about certain individuals. The two pairs (Robespierre – Saint-Just and Danton – Desmoulins) come to mind right away. They are constructed as parallels at least in some aspects and at least to some extent.

Wouldn't that, however, put Saint-Just and Desmoulins on the same/similar level, aren't they the ones who creat a parallel pair? Well, yes and no. I think they are a unit when it comes to personal matters, for rather obvious reasons. But I also think they are both put in similar situations, and yet their thinking is polar opposite of each other. They are both allowed to Robespierre's most personal sphere, and yet their reactions are completely different, which is one among the reasons as to why one of them meets a sad end by all accounts, and the other can die somewhat happy (as I will always mantain: if Przybyszewska managed to finish Thermidor, I am one hundred percent sure she would depict Antoine as one dying boldly and proudly, if only beause he died for a great cause and alongside Robespierre). On the other hand, spiritually and mentally, Camille resembles Maxime way, way more than Danton. They are both... maybe not exactly soft, but emotional. The main difference between them is Maxime is able to rein his feelings in when necessary (again, not always, not completely; vide his late night visit at Desmoulins', vide his attempt and saving him from the Luxembourg Palace), but as far as differences go, this one is actually minor. They are put in different positions, but their reactions are similar.

I would also wager to say Saint-Just and Robespierre don't have that much in common with each other in the plays, leaving out their political stances and their relationship. They are very different in terms of character traits: Maxime is more forgiving, calmer, quieter in all aspects. Antoine is more of a quicksilver, and also is regarded more as a tool in Maxime's hands, which I mean in the best way possible. While he has his own opinions, sometimes quite different to that of Robespierre's, he only entertains them in Maxime's presence, so that no one can put a splinter between them and turn them against each other. When they are turned against each other (during their quarrels, yes, but also during Thermidor, which is a beautiful study of such a case), he defers to Maximilien humbly and holds no grudges against him. This is pretty much the only soft side he ever presents to the audience, for when facing any other characters, he is sarcastic if not downright hostile, the only exception I can think of being Eleonore. He's not gentle, not even with Robespierre whom he respects so much. (I cannot get over how badly Wajda interpreted this in his movie, where in his very first scene Antoine brings Maxime an apple-tree branch in full blossom; while a sweet gesture, it made little sense, for the director not only didn't establish their special bond in any way, cutting their very important scene in Act II and a lot of their exchange of words in Act V out, but completely ignored the fact that in the play they did talk about trees blossming, but it was Maxime who pointed this out to Antoine. Honestly, it would make much more sense if in the movie he was the one giving Antoine flowers; altough I don't trust it would be executed well, so perhaps the best scenario would be to drop it altogether.)

This leaves Antoine and Danton as the unlikely pair. Here I wouldn't necessarily say they are put in different positions (following my train of comparison), because – depending on if you believe the confrontation between Danton and Robespierre to be honest or not – there is enough evidence in the play to mantain both of them want to establish power over nation through Robespierre. Danton is the villain of the play, but he isn't blind, he too wants to use Maximilien as a face of the dictature, as a tool to obtain more "normal" power for himself (normal power here would equal to money, respect, high office; the "abnormal" power is what Robespierre sort-of-dreams-of, an influence over people to direct them into doing what is necessary for the good of the whole of the nation, or better yet, the world). And Antoine wants more or less the same thing, the exception being he doesn't care at all for personal gains. He doesn't necessarily believe in Robespierre's visions of the future, one could even argue he doesn't understand them (this is clearly shown in Thermidor, where he reacts with a headache once Robespierre unfolds his plan in front of him: Stop it, Maxime. I can't keep up with you anymore.); he does, however, see the neccesity of establishing the dictature or some other extraordinary mean to obtain the total power over the state. Both he and Danton are blessed with a far-fetching political vision, the only thing differentiating them from Robespierre is that he's a much more brilliant chess player than any of them, when they can see few moves forward, he's already seen all the possible outcomes of the match. And all of these outcomes are bad, for Maxime is characterised as a pessimist, while Antoine and Danton are, generally speaking, optimistically inclined. Youthful foolishness indeed, except Antoine is not foolish! He's just optimistic. In Danton, the optimism takes a form of boldness and bravado, in Saint-Just it manifests as an unwavering faith in the one he considers to be so much more superior to himself, and also a certain amount of contempt for the ones he considers to be inferior. This is another trait he shares with Danton, and we have to admit, Przybyszewska did a really good job at presenting the same trait in them both in such different ways, that we like one, hate the other.

There is also the matter of how they treat Camille and what they think of him. Here, both are jealous, I think. Jealous of the special place Camille has in Robespierre's heart, scornful of his abilities as a politician and a journalist, disinclined to him as a person. Danton cares for him as far as his utility in being a leverage on Robespierre goes, but I don't think he hoards any warm feelings for him personally, and I don't say it only because he was willing to sacrifice Camille purely out of spite. A much better example to show what I mean is that Danton seems to have a much better functioning, more honest and professional relationship with Delacroix than with Camille, whom he keeps in the dark about absolutely everything from start to finish. I don't know if it was meant to be a symbol or not, but in their very last scene in the jail cell, Camille has to beg Danton not to snuff out the candle, which Danton does, albeit very reluctantly. In turn, Saint-Just talks about Camille in language dripping with contempt and jealousy of purely personal kind, offending him left and right, right to Robespierre's face – not to hurt Maxime, but to "open his eyes", so to speak. In one particularly harsh sentence he compares Camille to a dog, a child and a prostitue all in one breath. He not only doesn't regard him as an opponent, but barely recognizes him as a human being worth respect, in which he is sadly very similar to Danton.

Weirdly enough, they both regard Maximilien as human, which I think is interesting to notice. It would be really easy to write them in such a style that leaves way for them to see Robespierre as something more, something almost extraterrestrial, somebody who posseses abilites greater than normal humans do. And yet:

The first image is from The Last Nights of Ventose, my own translation, and it's directly from Antoine's compassionate speech. I didn't include Robespierre's response, because he just deflected, but deflection does mean he doesn't fully agree, so it's yet another similarity.

One more thing that comes to mind in a comparison like this is that Danton threatens Robespierre with the ultimate power. He doesn't think that Maxime will be able to live with it, with himself, if he ever decides to go this one step futher and become a dictator. Is this is because he wouldn't be able to live with himself, or does he truly underestimate Maxime, or he simply wants to make sure Maxime would not go in this direction precisley because he knows he would then be ustoppable? How very telling then, that in Antoine's mouth the very same thing is not a threat, but a promise! This ultimate power is born out of necessity, and it's a grace for the whole nation, because no other person could bear the weight of this "crown", but Maxime.

The main difference between Saint-Just and Danton, I think, is something which we have to believe, it's not written clearly anywhere, and this is also the thing I briefly touched uppon in the aforementioned post: we have to believe that Antoine has pure intentions, because we sure know Danton does not. These were the embers fueling the suspiscion in Maxime when he couldn't understand why Antoine would possibly push for the dictature so much – is his heart pure? This sounds overly dramatic, perhaps, but I think this dramaticism aligns perfectly with Maxime's overall characterisation. I think all readers believe in his good intentions, and the parallels constructing the characters help immensely in this judgement, for if Danton is rotten to the core, Antoine is as steady and pure as a marble column. Robespierre even calls one a pig, while the other deserves to be named an Apostle of liberty.

There is, however, another similarity between them, too. Both Antoine and Danton are willing to be dishonest in order to achieve their goals. This is this one thing that's hard for Robespierre to swallow, for he – like Camille – values honesty really highly and if he could, he'd always act honestly. Saint-Just, not to mention Danton, has no such scrupules. He sees the greater necessity as something erasing all other circumstances, and for this greater picture he is willing to sacrifice some of his integrity as a human being. With Danton, the situation is even less complex, for I don't believe he would be sacrificing his integrity in any way – this dishonesty lays at his very core and comes natural to him.

The arguments Saint-Just presents, and which differs from Robespierre's point of view, are also different from that of Danton's. Danton's vision of the present is filled with contempt for the people, for the masses who are less brilliant than him and few others are. It is worth noting that Przybyszewska really did think like this, this is something she believed in and while reading Danton's speeches in Act II Scene 3, what we actually hear is her own train of thoughts. The only difference is that she didn't disdain the people they way he did. She thought that being a mass, an unnamed pulp of flesh is not a bad thing (it was perhaps unfortunate, and I am sure thinking she was a genius like Robespierre helped her in maintainign this view). Base material is a nourishment for those who will lead these masses. We – the lesser people – are absolutely necessary for them – the greater ones – so that they can lead us out of the night and into the new epoch of enlightement, and there is nothing humiliating in being this nourishment/tool/base. Danton understood it only partially, for he wasn't ready for the greatest sacrifice of all: to be a genius, one has to get rid of everything personal, all needs and desires must be kept aside, and never again spoken of. Robespierre understood it, and I think Antoine did too. I think the best evidence for it is that he said, that he doesn't consider himself to be Robespierre's equal. Recently I hoped to prove it was a silent declaration of love; now I want to point out it is one because it showed Robespierre that Antoine understood this great sacrifice one has to make in order to be a leader, and in his own way, he has already done this. He has brushed aside personal vain and glory, his amour-propre, he degraded himself in order to magnify Maxime's importance. Danton may say: It's you whom I adore, but it is Antoine who shows it through his actions as well as his words.

#do you think they are constructed as parallels or am i delirious?#sprawa dantona#the danton case#L'Affaire Danton#Stanisława Przybyszewska#stanislawa przybyszewska#Maximilien Robespierre#maksymilian robespierre#antoine saint just#Antoni saint just#georges danton#jerzy danton#frev#french revolution#literary analysis

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

I cannot claim to know about this play more than some others (Ewa Graczyk, Jagoda Hernik-Spalińska, Kazimiera Ingdahl and Maria Janion, in alphabetical order, are the official Horsewomen of the Apocalypse in this topic), with a lot to bring to the table, and so I will sometimes discuss parts of it which are - at the very least at the first glance - absolutely and doubtlessly simple; but by discussing them I hope to be able to bring into the discussion some new material, new evidence, perhaps - for the contrary of the popular belief.

I remember when I first read the scene between Danton and Robespierre, I was completely mystified, just as Maxime. To somebody who at that point knew nothing about the historical events, the exchange between them was very logical (and everyone knows how hard it is to obtain, especially in a piece of media where the author blatantly favours one of the characters over another). I am very glad then, to be able to say that while Przybyszewska did everything she could to humiliate and belittle Danton in the more visual aspects of the scene - his gestures, movements, actions, mimicry, even the sound of his voice etc. - she didn't bother making him out to be a complete clown. His arguments are populistic, but that's not necessarily a bad thing when you're n politician aspiring to be even more than that. Perhaps she thought that painting him out to be a weakling would somehow diminish Robespierre's awesomeness, which is a valid concern. For Robepsierre has little left to do in this scene - it is made out to ba a confrontation between them, of sorts, but is it one, really? I don't think so, not for the large part of it. Robespierre comes in, dishes out few sarcastic lines, looks at Danton with disgust and contempt and then crushes him in a yet another sarcastic line and then leaves. There isn't that much he can do not only to participate in the exchange, but to be visually and audially appealing to the audience as a character in a play. And even though we all know staging The Danton Case is a secondary affair, the main thing you can do with it is to read it and ponder over it, when you do stage it, a lot of responsibility rests on the actors recreating the part. Which is why choosing a good actor can, potentially, make all the difference, sometimes going as far as completely changing the way you view the very same scene you read earlier.

I have always assumed by "the same man" they meant Robespierre. It makes some sense in the light of the conversation, altough I have to admit it makes little sense in the light of Robespierre's reaction. The question thus presented to us is: do we go by what is written, do we percieve a play as a piece of fiction in a real world, OR do we immerse ourselves in the fictional world, suspend our disbelief and for a moment treat it as an alternate reality of sorts?

Polish director Jan Klata has managed to put on stage a compelling retelling of The Danton Case and I would like to present to you a scene from his version, which we're lucky enough to have on YT, with translation courtesy of @that-one-revolutionary. I've seen the play in its entirety: some metaphors were heavy-handed to say the least, some aspects I wish he'd done differently, but all in all, when choosing the main protagonist, the director casted in the role a truly splendid actor (please note that Marcin Czarnik was young. Young! It made all of the difference and it's worth watching if only for that), who brought home some of the points of character of Robespierre's which could have easily been brushed aside in order to highlight some other aspects of the conversation (the most famous example of this would be the very same scene from Wajda's movie, where the appealing and in all aspects imposing Gerard Depardieu dominantes the scene, thus presentign it in a very different ligt). While it can be read as a political statement, or a match of two great personalities, or a display of cunning on either part, Klata (or Czarnik; it's hard for me to say what the director tried to do with it, a lot of Robespierre's quirks, mimicry, gestures etc. seemed to come directly from the actor, which I can only say because I've seen him in other things and that's sort of his style of acting; all in all, I'll try to treat this not as a discussion over this particular staging, because for that I lack needed data, but it's unavoidable in the long run at least at some points, so please bear that in mind) treats the conversation itself as a minor thing in comparision to what is going on in Maxime's mind at the moment. Just look at this: there is no significance brought into their meeting, no change of the scenery, nothing indicates this meeting is special in any way. The logical conclusion is, then: it's not special. Both Danton and Robespierre seem to treat this as a step which cannot be avoided, but which bears no great weight either. The only reason they agreed to make this step altogether is - for "the same man". For Camille.

I do think Przybyszewska's intention was actually to disguise Maxime under this vague title. If this is a play about love - as I will always state it is - she wanted to underline the fact some people will be hatefully loved by those who are beneath them, who have nothing whatsoever in common with the object of their affection simply because the loved one is so great, so genius, so shining and bright it is impossible not to love them. I think this is the relationship between Danton and Robespierre (that is, on Danton's part) up until this point in the play. Danton idolizes Robespierre against his will (against both of their wills, really), because Robespierre is truly made out to be a demi-god at the very least. If you could team up with a hero like this, you should. So Danton goes through a humiliating process of trying to reconcile with Maxime, because humiliation, if everything paid off in the end, would be worth it. That Robespierre doesn't reciprocate the affection is simply a further proof that he is above Danton in every way.

Klata-Czarnik duo seems to have gone into another, subtler direction though. The man that both politicians make an exception for seems to be Camille, moreso because Robespierre loves him than because Danton has any special feelings for him. What is his relationship with Camille, anyway? They are cordial enough, but always a bit on the edge, and we know that Danton doesn't know everything that Camille thinks and feels in regards to Robespierre, mostly because he doesn't care that much, but also because he is characterised as a brute, and this simply goes above his head, it's too subtle, too delicate of a feeling for him to know it. It is also clear he knows Camille pretty well, but he doesn't know his soul, so to say. Therefore, he cannot actually love him, not to the point to make him the one and only excpetion from his otherwise coldly and precisley calculated plans.

Is there, however, a scenario in which Camille could be Danton's exception? Yes, when it becomes more about Robepierre than about Camille. When Camille is sort of offered as a mean to lure Robepierre in. Danton could make this exception only if it meant getting what he wanted (which is later mirrored by his blatant admission that the only reason he lets Camille take the fall with him is to deny Robespierre any joy in life after this point).

Robespierre, however, doesn't see it this way. He actually makes the exception for Camille and I think Danton's words – whatever he means by them, whichever interpretation we think is correct – put him on alert, for the fear of having his secret discovered. In the video linked above it is even more than that – once Robespierre hears Danton indirectly name "the same man", he gets aggressively defensive. For him to have someone like Danton talk almost openly about what he treats as his personal secret (a secret that Danton, being in great familiarity with Camille, could potentially know for certain) is equal with defiling it. I have violated your secret. Do you know what he says in the original? I have raped your secret. It really brings into the focus how much “the secret” needs to be protected, and how much it will hurt Maxime once it’s uncovered and destroyed.This is what he fears pretty much for the entirety of the conversation, his suspiscion somewhat confirmed when Danton says: No catchphrases, Robespierre. I know you.

As I mentioned earlier, the shift in my reading of the scene was prompted by the video. It is worth observing what exactly does Robespierre do when mentioing Camille by surname – he gets visibly more upset, he ponders for a split second for the best way to talk about him. His choice of words is interesting as well:

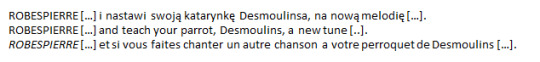

Both translations here are poor and I quite like what that-one-revolutionary did with it. "Katarynka" is a music-box, so "an instrument" fits much better (not to mention the obvious English connection to the phrase "play like a fiddle", which is adequate here). A parrots is after all a living being, something with a will of its own, if steered by more powerful handlers. But admitting that Camille, from his own free will decided to go against Maxime and everything that Maxime believes in is much harder for Robespierre than calling him an inanimate object, which can be unwittingly used by people with their own agenda. That leaves Camille almost blameless, perhaps careless and foolish, but not responsible fo anything that has transpired.Calling him names serves another purpose as well, which is to steer away the suspiscion that Robespierre protects Camille becuase he cares about him in a special way. He knows there are Danton's accomplices turning ears by the door, so he doesn't want to give himself away with his care and concern.

Ultimately, what do you believe, whom do you think they were referring to I think says a lot about what you think about Maxime's state of mind at the time. Danton's too, though, it can be used as a litmus test whater or not you believe he was honest in idolising Robespierre and offering him his adoration and obedience. In some stagings it will be presented as true, in some as a lie, and that's the beauty of adapting a piece of literature, there are so many options, all blooming from the same roots.

#sprawa dantona#the danton case#L'Affaire Danton#stanisława przybyszewska#stanislawa przybyszewska#maximilien robespierre#maksymilian robespierre#kamil desmoulins#camille desmoulins#georges danton#jerzy danton

14 notes

·

View notes

Photo

This is going to be less of a literary analysis and more of a comparison of different translations, which in their minutiae sometimes give way for a completely different understanding of the scene.

Because, as you should be made aware of, this one simple phrase from Robespierre's lips was hellishly difficult to translate properly.

"Nudzić" means both "to be a bore" and "to talk nonsense". Impossible to differentiate between them without context, but even within context, in this particular scene it is impossible to tell which one Przybyszewska had in mind (to be honest, I think she did not simply overlook it - she made far too many rewrites and reviews for that to be possible in any way), because while Robespierre's statement carries a double meaning, Camille's response is definitely in the realm of “to bore" etc. I am, however, partial to the second meaning being the correct one, which would mean that for once in their life the French translation is actually better and clearer than the English one (a rare occurence).

Because it never made any sense to me why should Robespierre find Camille boring, of all adjectives, in this particular instance? I can accept it being a low-level insult, something aimed at Camille in order to pour a bucket of cold water over his passion. And Camille's cheeky response falls well within this image. But French translation simply makes more sense. "Camille, don't talk nonsense. - I am not talking nonsense.". Simple as that, makes more sense, still reads both as a banter and as a weak attempt at disarming Camille and pulling him out of the moment.

It is also worth noting on the side that this is one of rare instances where the English version messes up with punctuation, and French does not. But it makes little difference this time.

#sprawa dantona#the danton case#l'affaire danton#stanisława przybyszewska#stanislawa przybyszewska#camille desmoulins#maximilien robespierre

4 notes

·

View notes