#I am the epitome of linguist meaning NO I CANNOT SPEAK THESE LANGUAGES BUT I CAN TELL YOU FUN FACTS ABOUT THEM THAT I THINK ARE NEAT

Text

I am trying to pick up Swedish again after taking four German classes in Uni…. At this rate I am creating some unholy matrimony of Germanic languages. Who next will be added to the soup

#mind you my German is also shit#put all the little conjunctions and prepositions are now sprinkled into Swedish#I’m trying to think and I just go: UND#what the fuck is UND the word I’m looking for is OCH#I am the epitome of linguist meaning NO I CANNOT SPEAK THESE LANGUAGES BUT I CAN TELL YOU FUN FACTS ABOUT THEM THAT I THINK ARE NEAT#for example I like Swedish noun paradigms#Swedish is what got me into linguistics in the first place so I am trying to reignite that live because I remember how it used to fill me#with so much love hope and purpose#maybe maybe maybe I’ll actually use all those grammar books I have#given that I can ACTUALLY read the IPA transcription#although actually I’d love to get some more textbooks that are… more linguistically inclined#I’ve been using this book: German Phonetics and Phonology; Theory and Practice by O’Brien and Fagan#for a phonetics project and … honestly I need something like that but for Swedish#it pains me how much I used to know about Swedish that I’ve just…… lost#but I’m coming back into it with more knowledge about language#and also more knowledge about Swedish typologically… so that’s useful#Irving rambles#language learning

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fake Hafez: How a supreme Persian poet of love was erased | Religion | Al Jazeera

This is the time of the year where every day I get a handful of requests to track down the original, authentic versions of some famed Muslim poet, usually Hafez or Rumi. The requests start off the same way: "I am getting married next month, and my fiance and I wanted to celebrate our Muslim background, and we have always loved this poem by Hafez. Could you send us the original?" Or, "My daughter is graduating this month, and I know she loves this quote from Hafez. Can you send me the original so I can recite it to her at the ceremony we are holding for her?"

It is heartbreaking to have to write back time after time and say the words that bring disappointment: The poems that they have come to love so much and that are ubiquitous on the internet are forgeries. Fake. Made up. No relationship to the original poetry of the beloved and popular Hafez of Shiraz.

How did this come to be? How can it be that about 99.9 percent of the quotes and poems attributed to one the most popular and influential of all the Persian poets and Muslim sages ever, one who is seen as a member of the pantheon of "universal" spirituality on the internet are ... fake? It turns out that it is a fascinating story of Western exotification and appropriation of Muslim spirituality.

Let us take a look at some of these quotes attributed to Hafez:

Even after all this time,

the sun never says to the earth,

'you owe me.'

Look what happens with a love like that!

It lights up the whole sky.

You like that one from Hafez? Too bad. Fake Hafez.

Your heart and my heart

Are very very old friends.

Like that one from Hafez too? Also Fake Hafez.

Fear is the cheapest room in the house.

I would like to see you living in better conditions.

Beautiful. Again, not Hafez.

And the next one you were going to ask about? Also fake. So where do all these fake Hafez quotes come from?

An American poet, named Daniel Ladinsky, has been publishing books under the name of the famed Persian poet Hafez for more than 20 years. These books have become bestsellers. You are likely to find them on the shelves of your local bookstore under the "Sufism" section, alongside books of Rumi, Khalil Gibran, Idries Shah, etc.

It hurts me to say this, because I know so many people love these "Hafez" translations. They are beautiful poetry in English, and do contain some profound wisdom. Yet if you love a tradition, you have to speak the truth: Ladinsky's translations have no earthly connection to what the historical Hafez of Shiraz, the 14th-century Persian sage, ever said.

He is making it up. Ladinsky himself admitted that they are not "translations", or "accurate", and in fact denied having any knowledge of Persian in his 1996 best-selling book, I Heard God Laughing. Ladinsky has another bestseller, The Subject Tonight Is Love.

Persians take poetry seriously. For many, it is their singular contribution to world civilisation: What the Greeks are to philosophy, Persians are to poetry. And in the great pantheon of Persian poetry where Hafez, Rumi, Saadi, 'Attar, Nezami, and Ferdowsi might be the immortals, there is perhaps none whose mastery of the Persian language is as refined as that of Hafez.

In the introduction to a recent book on Hafez, I said that Rumi (whose poetic output is in the tens of thousands) comes at you like you an ocean, pulling you in until you surrender to his mystical wave and are washed back to the ocean. Hafez, on the other hand, is like a luminous diamond, with each facet being a perfect cut. You cannot add or take away a word from his sonnets. So, pray tell, how is someone who admits that they do not know the language going to be translating the language?

Ladinsky is not translating from the Persian original of Hafez. And unlike some "versioners" (Coleman Barks is by far the most gifted here) who translate Rumi by taking the Victorian literal translations and rendering them into American free verse, Ladinsky's relationship with the text of Hafez's poetry is nonexistent. Ladinsky claims that Hafez appeared to him in a dream and handed him the English "translations" he is publishing:

"About six months into this work I had an astounding dream in which I saw Hafiz as an Infinite Fountaining Sun (I saw him as God), who sang hundreds of lines of his poetry to me in English, asking me to give that message to 'my artists and seekers'."

It is not my place to argue with people and their dreams, but I am fairly certain that this is not how translation works. A great scholar of Persian and Urdu literature, Christopher Shackle, describes Ladinsky's output as "not so much a paraphrase as a parody of the wondrously wrought style of the greatest master of Persian art-poetry." Another critic, Murat Nemet-Nejat, described Ladinsky's poems as what they are: original poems of Ladinsky masquerading as a "translation."

I want to give credit where credit is due: I do like Ladinsky's poetry. And they do contain mystical insights. Some of the statements that Ladinsky attributes to Hafez are, in fact, mystical truths that we hear from many different mystics. And he is indeed a gifted poet. See this line, for example:

I wish I could show you

when you are lonely or in darkness

the astonishing light of your own being.

That is good stuff. Powerful. And many mystics, including the 20th-century Sufi master Pir Vilayat, would cast his powerful glance at his students, stating that he would long for them to be able to see themselves and their own worth as he sees them. So yes, Ladinsky's poetry is mystical. And it is great poetry. So good that it is listed on Good Reads as the wisdom of "Hafez of Shiraz." The problem is, Hafez of Shiraz said nothing like that. Daniel Ladinsky of St Louis did.

The poems are indeed beautiful. They are just not ... Hafez. They are ... Hafez-ish? Hafez-esque? So many of us wish that Ladinsky had just published his work under his own name, rather than appropriating Hafez's.

Ladinsky's "translations" have been passed on by Oprah, the BBC, and others. Government officials have used them on occasions where they have wanted to include Persian speakers and Iranians. It is now part of the spiritual wisdom of the East shared in Western circles. Which is great for Ladinsky, but we are missing the chance to hear from the actual, real Hafez. And that is a shame.

So, who was the real Hafez (1315-1390)?

He was a Muslim, Persian-speaking sage whose collection of love poetry rivals only Mawlana Rumi in terms of its popularity and influence. Hafez's given name was Muhammad, and he was called Shams al-Din (The Sun of Religion). Hafez was his honorific because he had memorised the whole of the Quran. His poetry collection, the Divan, was referred to as Lesan al-Ghayb (the Tongue of the Unseen Realms).

A great scholar of Islam, the late Shahab Ahmed, referred to Hafez's Divan as: "the most widely-copied, widely-circulated, widely-read, widely-memorized, widely-recited, widely-invoked, and widely-proverbialized book of poetry in Islamic history." Even accounting for a slight debate, that gives some indication of his immense following. Hafez's poetry is considered the very epitome of Persian in the Ghazal tradition.

Hafez's worldview is inseparable from the world of Medieval Islam, the genre of Persian love poetry, and more. And yet he is deliciously impossible to pin down. He is a mystic, though he pokes fun at ostentatious mystics. His own name is "he who has committed the Quran to heart", yet he loathes religious hypocrisy. He shows his own piety while his poetry is filled with references to intoxication and wine that may be literal or may be symbolic.

The most sublime part of Hafez's poetry is its ambiguity. It is like a Rorschach psychological test in poetry. The mystics see it as a sign of their own yearning, and so do the wine-drinkers, and the anti-religious types. It is perhaps a futile exercise to impose one definitive meaning on Hafez. It would rob him of what makes him ... Hafez.

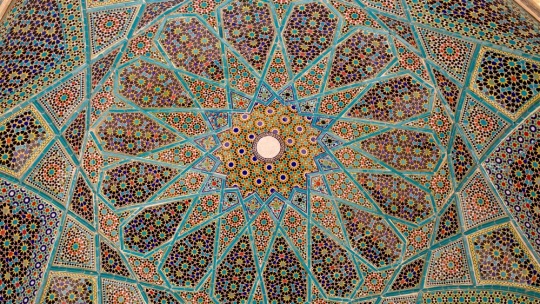

The tomb of Hafez in Shiraz, a magnificent city in Iran, is a popular pilgrimage site and the honeymoon destination of choice for many Iranian newlyweds. His poetry, alongside that of Rumi and Saadi, are main staples of vocalists in Iran to this day, including beautiful covers by leading maestros like Shahram Nazeri and Mohammadreza Shajarian.

Like many other Persian poets and mystics, the influence of Hafez extended far beyond contemporary Iran and can be felt wherever Persianate culture was a presence, including India and Pakistan, Central Asia, Afghanistan, and the Ottoman realms. Persian was the literary language par excellence from Bengal to Bosnia for almost a millennium, a reality that sadly has been buried under more recent nationalistic and linguistic barrages.

Part of what is going on here is what we also see, to a lesser extent, with Rumi: the voice and genius of the Persian speaking, Muslim, mystical, sensual sage of Shiraz are usurped and erased, and taken over by a white American with no connection to Hafez's Islam or Persian tradition. This is erasure and spiritual colonialism. Which is a shame, because Hafez's poetry deserves to be read worldwide alongside Shakespeare and Toni Morrison, Tagore and Whitman, Pablo Neruda and the real Rumi, Tao Te Ching and the Gita, Mahmoud Darwish, and the like.

In a 2013 interview, Ladinsky said of his poems published under the name of Hafez: "Is it Hafez or Danny? I don't know. Does it really matter?" I think it matters a great deal. There are larger issues of language, community, and power involved here.

It is not simply a matter of a translation dispute, nor of alternate models of translations. This is a matter of power, privilege and erasure. There is limited shelf space in any bookstore. Will we see the real Rumi, the real Hafez, or something appropriating their name? How did publishers publish books under the name of Hafez without having someone, anyone, with a modicum of familiarity check these purported translations against the original to see if there is a relationship? Was there anyone in the room when these decisions were made who was connected in a meaningful way to the communities who have lived through Hafez for centuries?

Hafez's poetry has not been sitting idly on a shelf gathering dust. It has been, and continues to be, the lifeline of the poetic and religious imagination of tens of millions of human beings. Hafez has something to say, and to sing, to the whole world, but bypassing these tens of millions who have kept Hafez in their heart as Hafez kept the Quran in his heart is tantamount to erasure and appropriation.

We live in an age where the president of the United States ran on an Islamophobic campaign of "Islam hates us" and establishing a cruel Muslim ban immediately upon taking office. As Edward Said and other theorists have reminded us, the world of culture is inseparable from the world of politics. So there is something sinister about keeping Muslims out of our borders while stealing their crown jewels and appropriating them not by translating them but simply as decor for poetry that bears no relationship to the original. Without equating the two, the dynamic here is reminiscent of white America's endless fascination with Black culture and music while continuing to perpetuate systems and institutions that leave Black folk unable to breathe.

There is one last element: It is indeed an act of violence to take the Islam out of Rumi and Hafez, as Ladinsky has done. It is another thing to take Rumi and Hafez out of Islam. That is a separate matter, and a mandate for Muslims to reimagine a faith that is steeped in the world of poetry, nuance, mercy, love, spirit, and beauty. Far from merely being content to criticise those who appropriate Muslim sages and erase Muslims' own presence in their legacy, it is also up to us to reimagine Islam where figures like Rumi and Hafez are central voices. This has been part of what many of feel called to, and are pursuing through initiatives like Illuminated Courses.

Oh, and one last thing: It is Haaaaafez, not Hafeeeeez. Please.

The views expressed in this article are the author's own and do not necessarily reflect Al Jazeera's editorial stance.

This content was originally published here.

241 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Polyglot Vampire: The Politics of Translation in Bram Stoker's Dracula

Katy Brundan, The Polyglot Vampire: The Politics of Translation in Bram Stoker's Dracula, Forum for Modern Language Studies, Volume 52, Issue 1, January 2016, Pages 1–21.

________________________________________________________________

I’ve been fascinated lately with Count Dracula’s ability to absorb through blood his victims’ language and personal traits as well as one might say their identity. So I googled this phenomenon and the closest I could find (yet) was this article.

I quote it extensively below.

By situating Dracula's origins in the linguistic ‘whirlpool’ of Transylvania, Stoker deliberately exploits the potential of a disputed territory occupied by multiple national-linguistic groups during its turbulent history. Dracula's inevitable mastery of languages over the centuries suggests that being undead gives one unique linguistic advantages. Indeed, Dracula provides a solution to the problem voiced by Benedict Anderson: ‘[W]hat limits one's access to other languages is not their imperviousness, but one's own mortality.’ Dracula's preternatural linguistic skills gained from defying mortality complement his embodiment of paradigms signified by the Latin prefix trans, meaning ‘across’, ‘beyond’ and ‘from one state to another’.

Dracula's fundamental purpose is one of translation: translating (transferring across) bodies from one state to another, taking them beyond the reaches of Christianity and beyond death itself.

Dracula even has himself ‘translated’ in earth-filled coffins from place to place, since one of the definitions of ‘to translate’ in English is, precisely, to move the dead body of a ‘hero or great man’ from one place to another (OED). The premise of Stoker's novel thus presents us with a polyglot vampire who exerts control over his victims through his unique abilities of bodily and linguistic translation, resisting the forces of monolingualism as he resists mortality. The afterlife of Stoker's undead Count finds its epitome in relationships mediated not simply through blood, but through polyglossia, linguistic mastery, and the translated text.

Dracula's battle for bodies is waged through language(s) and through his superior translation abilities.

Quite pointedly, Dracula makes his first appearance accompanied by a phrase in German, translated into English. One of the coach passengers whispers the famous line ‘“Denn die Todten reiten schnell.” – (“For the dead travel fast”)’ (p. 10) from Gottfried August Bürger's Gothic ballad ‘Lenore’ (1773). While Harker correctly recognizes this line, he fails to translate his own position into this quotation, in which a ghostly rider appears as a dead soldier anxious to take his lover to her marriage bed/grave. The translated phrase constructs Harker's relationship to Dracula in erotic terms, since Harker clearly occupies the position of the female victim about to be swept away by Dracula, the undead ‘lover’. Dracula has already written to tell Harker he is ‘anxiously expecting’ him (p. 4) and arrives early at the rendezvous to hasten the Englishman away in his carriage. Dracula's homoerotic inclination towards Harker in the first part of the novel simply follows the logic of Bürger's text. Indeed, ‘the Count must have carried’ Harker to bed after the Englishman faints on being approached by the female vampires (p. 40), as if taking him to the ballad's marriage bed and potential grave. Dracula's power over Harker thus begins with a translated text that implies an intimacy between the two men. Bürger's ballad was particularly popular in translation, and arguably ‘no German poem has been so repeatedly translated into English as Ellenore’ (it was translated by Sir Walter Scott and Dante Gabriel Rossetti, among others), implying that the text itself provoked English desire. Stoker's use of this poem suggests not only that Dracula brings with him a German Gothic aesthetic but also that he heralds the desire and intimacy inherent in translation. Meanwhile, the English Harker is desperately deficient in his ability to translate the implications of this German text constructing him as the passive beloved.

Dracula's position of power is solidified by his ‘excellent’ German, which makes an unsettling contrast with the difficulty others have speaking the lingua franca, such as the Bistritz coach driver whose German is ‘worse’ even than Harker's (pp. 11, 9). Once in the castle, Harker's submissive, feminized relationship to Dracula (‘I am so absolutely in his power;’ p. 40) is heightened by Dracula's remarkable linguistic versatility. The Count speaks German, orders the Szgany gypsies apparently in Romany (Harker cannot even understand their sign language ‘any more than I could their spoken language’), commands the Slovaks who move his boxes of earth (presumably in Slovak), and discourses rather pompously with Harker in English (p. 41). If Dracula is indeed ‘that Voivode Dracula who won his name against the Turk’ (p. 240) in the fifteenth century, as Van Helsing believes, then he has had centuries to hone his linguistic skills. Living as a boyar in Transylvania throughout this period would make Dracula a speaker of probably a dozen languages.The fact that we overlook Dracula's linguistic mastery reflects a projection of our own relatively monolingual environment back onto Stoker's novel.

Harker notes that Dracula speaks ‘excellent English, but with a strange intonation’ (p. 15), an uncanny effect caused by the vampire having taught himself by importing books and newspapers. Dracula's own avidity in studying English indicates the slippage of the language-learner into the linguist-spy:

I long to go through the crowded streets of your mighty London, to be in the midst of the whirl and rush of humanity, to share its life, its change, its death, and all that makes it what it is. But alas! as yet I only know your tongue through books. To you, my friend, I look that I know it to speak. […] Well I know that, did I move and speak in your London, none there are who would not know me for a stranger. That is not enough for me […]. I am content if I am like the rest, so that no man stops if he sees me, or pause in his speaking if he hear my words, to say, ‘Ha, ha! a stranger!’ […] I would that you tell me when I make error, even of the smallest, in my speaking. (p. 20)

Dracula does not wish to be marked by his accent as a ‘stranger’ (this word alone makes it clear he is a foreigner), since mastering the English language is key to seizing English bodies. This speech itself is ‘marked’ by inaccurate grammar, since the linguist-spy has much to learn from Harker, who is now forced into the treacherous position of language teacher by virtue of his inability to speak any other language.

Dracula the polyglot and spy may have found a model in Arminius Vambéry (1832–1913), celebrated linguist and professor of Oriental languages at Budapest University. Vambéry was described by The Spectator in 1884 as ‘one of the most remarkable polyglots of our time’, who was known for his flamboyant lectures. However, Vambéry puts a new twist on the Italian pun traduttore, traditore (translator, traitor) by combining the skills of translator and linguist with those of spy and double agent. Stoker met Vambéry on two occasions and used his first name in Dracula when Van Helsing explains that he has ‘asked my friend Arminius, of Buda-Pesth University, to make [Dracula's] record’ (p. 240). Stoker wrote of the real Vambéry: ‘He is a wonderful linguist, writes twelve languages, speaks freely sixteen, and knows over twenty.’ Vambéry taught himself languages without a teacher, and sometimes without even a dictionary, strangely resembling Dracula's method of language-learning from books alone. Stoker recalled Vambéry telling him: ‘[I]n Central Asia we travel not on the feet but on the tongue.’This might make us think of Dracula's position as a man who does not travel by ‘feet’ as much as by wings and his own linguistic versatility. Vambéry made a career by his tongue, famously travelling along the Silk Road to Afghanistan disguised as a lowly Muslim dervish. He then spent decades working as a British spy in Turkey, as recently released archival material confirms, his professorship in linguistics ‘merely a cover’ for his spying activities. Vambéry's vaunted nationalist goal of analysing Turkish dialects to prove an ancient and glorifying relationship with Hungarian ended in the service not of Hungary, but of Britain. However, the premise of the linguist-spy subordinating his preternatural skill with languages to aid the British imperial cause becomes reversed in Dracula. Instead, Stoker turns the model of the Orientalist linguist back against the West.

0 notes

Text

Expert: From the end of WWII until the present, the United States has been borrowing, inventing, or inverting terms to label other nations and their political systems. Eventually, the repertoire of politically motivated rhetorical gadgetries swelled to become a convenient ideological arsenal for US expansions into the sovereign domains of all nations. Noam Chomsky once noted, “Talking about American imperialism is rather like talking about triangular triangles.”1 Debating the rhetorical validity of Chomsky’s observation and if it effectively describes talking about the United States is not the subject of this article. However, the conclusion that US imperialism is highly adept at dispensing interminable triangular triangles is self-evident. Terms such as “American exceptionalism,” “leader of the free world,” “God bless America,” and “our great American democracy” to describe the United States, and terms such as “dictatorship,” “totalitarian,” “closed-nation,” “rogue state,” “state sponsor of terrorism,” “regime,” etc. to describe targeted states are littered throughout the American political lexicon. Could such terms shape policies and determine events? The manipulation of language can be baleful. In the documentary film Psywar, a compelling case is made that scourges, such as impoverishment and wars, arise from the abuse of language. Consider World War II. American Anti‑German propaganda used certain Third Reich terms (Lebensraum, Aryan race, Führer, Social Darwinism, etc.) as a rationale, among many others, to justify US entry into that war. In Vietnam, the catch phrase was to stop the “Communist domino” in South East Asia. In the invasion and occupation of Afghanistan and Iraq, the semantic ornamentation of US wars of aggression took the cynical names of “enduring freedom,” and “Iraqi freedom,” respectively. Emphatically, people need to be well aware of words and the meanings they impart. It is all too easy to latch onto and use terms that have been integrated into mainstream discourse from media ubiquity. Language has significance, and it helps to shape consciousness and actions. Knowing this, some people who crave wealth and power will manipulate language to satisfy their cravings. But when imperialist ambition for other nations’ assets or strategic locations becomes state policy, the results can be calamitous for nations targeted by imperialism. Hence, the idioms of US imperialism cannot simply be harmless cravings. What drives this imperialism is the quest for a global imperium, regardless of costs to others. Within this context, the terms Regime and Regime Change play a role in shaping the linguistic landscape for the US militarism and unchallenged world hegemony. Earlier in US history, President Thomas Jefferson epitomized that drive. Hypothesizing on the “inevitable” collapse of the Spanish Empire in Latin America, he stated that the United States could wait “until our population can be sufficiently advanced to gain it from them piece by piece.”2 Because of incessant state propaganda and the media’s absorption of ideologized terms, the rhetoric of regime and regime change have become so pervasive that even progressive outlets are not immune from it. To evaluate how these terms seep into and embed in the culture and conduct of political systems, we will discuss a typical case as represented by Aaron Maté, a host and producer for The Real News. On 25 April, The Real News carried an interview by Maté with former Bush administration official Lawrence Wilkerson. In the interview, Maté refers to the Syrian government as the “Assad regime.”When speaking of the US, however, he never uses the term “regime.”Maté refers to the “Trump administration” and the “Bush administration,” and Wilkerson speaks of the “Obama administration.” Because the term regime is ambiguous, highly politicized, exceedingly ideologized, often used out of context, and invariably employed by the West as an instrument of political defamation, why does this supposedly progressive, independent news outlet use a clear imperialist jargon to demonize foreign governments? Given that language conveys images through words, using figuratively pejorative wording such as regime implies that a government of such a country is illegitimate. Therefore, effecting “regime change” by military force becomes a purported corrective moral duty of the US. Has this been the case, for instance, with “regime change” in Iraq, Libya, and other Arab states? Let us dispense for one moment with linguistic gimmicks. Because Wilkerson and Maté spoke of “regime change” throughout the interview, why not opt for straightforward clarity and say the violent overthrow of a foreign government directly or through proxy! In the case of Syria, it should be emphasized that the overthrow is largely being driven by foreign actors. To dispel any misunderstanding on our part, and to clarify the intent of Maté, one of us, Kim, wrote to him. Here is the exchange: KP: In recent interviews, you use “Assad regime” but you never refer to a Bush/Trump regime. They are called administrations. Since “regime” is pejorative, why do you call the elected Syrian government a regime? AM: The Assads have been in power for more than four decades. And I don’t think Trump-Bush’s electoral victories and Assad’s are comparable — correct me if I’m wrong, but in the latter, there wasn’t voting outside of government areas and some foreign embassies. I can understand the argument against using regime if it can help legitimize regime change. What term would you use? KP: First, the business parties of the US have been in power several more decades — since the US was established on Indigenous territory. Second, the 2014 Syrian election was open to international observers; it had a 73.4% turnout that garnered 88.7% support for Assad (64% of eligible voters … which, I submit, obviates the criticism of “outside government controlled areas” … difficult to control when foreign mercenaries and terrorists are wreaking havoc in parts of the country). And you are certainly aware of criticisms of US “democracy” and voting there. I would refrain from using a pejorative term. I would refer to the “Syrian government” or the “Assad administration” … terms I use with the US or other western governments. I believe an unbiased (or a person hiding biases because most of us arguably have them) media person would not use (mis)leading language with readers/viewers. So I would not use the term “regime change.” I would say “coup” or “foreign-backed overthrow of an elected government.” Lastly, I submit the US has no business determining for Syrians how they will be led and who will lead them? AM: Exactly, the business parties have ruled in the US, not one intertwined family regime. I don’t see the 2014 elections, where opponents were state-approved and large parts of the country excluded, as you do. I think regime is exactly the right term for the Assad gang but I can see the argument for not using a pejorative term, even an accurate one. So I’ll consider it. I certainly agree re: your last point. Remarks It was rather unsettling when Maté stated, “I can understand the argument against using regime if it can help legitimize regime change. What term would you use?” [Emphasis added]. It seemed evident that Maté was aware that using the word regime would predispose for violent change. So Kim asked The Real News host for clarification. Maté replied, “I’m saying I wouldn’t want to use language that can can legitimate regime change. I think the Assad regime is a regime, a horrible one, but I don’t support regime change.” Maté calls the Assad government “the Assad gang.” This is problematic because Maté knows that George W. Bush launched the war that killed hundreds of thousands of people in Iraq and Afghanistan, yet did anyone hear Maté saying “the Bush gang”? We are also unaware of, to use the descriptor of Maté, the “Bush administration” (not a regime according to Maté) being described as “a horrible one” (although Maté might agree Bush was horrible; however, if one leaves unchallenged that the “Assad regime” is horrible,3 then the question arises whether the “Assad regime” is more horrible than the “Bush administration,” “Obama administration,” or “Trump administration”). We suspect that Maté decided to qualify the Assad government according to his ideological leaning and not according to neutral metrics of journalism or political judgement. Of interest, by saying, “I can see the argument for not using a pejorative term, even an accurate one,” Maté demonstrated an intention to persist in his prejudicial charge of “regime” despite his capability to see the “argument for not using a pejorative term.” Further, Maté questions the decades-long father-to-son Assad governance in Syria. We agree. However, such aspect must not be questioned parochially. First, the United States loves dynasties that serve its plans. One example is the Somoza dynasty in Nicaragua (1936-1974). The other was the planned transfer of power from Hosni Mubarak to his son Gamal that the US encouraged and blessed until the Egyptian people put an axe to that plan in 2011. Second, we should place the question of dynastic rule in the political context of independent states. That is, the status of who rules in an independent state is exclusively an internal affair of said state. Explanation: most modern nation-states—especially in Asia and Africa—that emerged after WWI and WWII are the result of myriad historical, domestic, and external (i.e., foreign power intervention) factors. (Israel, being a state created by the West as a homeland for Jewish Europeans is an exception. The western hemisphere, Australia, and Aotearoa/New Zealand are also another subject.) After the dust settled, many nation-states came to exist as political systems with boundaries arbitrarily demarcated by European powers. Consequently, we deem that criticizing, destabilizing, indicting, partitioning, or overthrowing the legitimate (according to prevailing international agreements) governments of these states is not only absurd but patently criminal. Legally and morally, no foreign states, institutions, groups, or individuals have any right to rearrange the political configuration and type of power of any other country. Of course, we have every right to question the power assets of a specific state if they negatively affect other nations. We also have the right to question the power structures of all other states be they the business duopoly of the United States, the medieval system of Saudi Arabia, or the moribund but obstinate colonialist system of Britain. Conclusion: Leaving aside the question of the moral cogency of the system of nation states, it is elementary to uphold the notion that the configuration of any national government is a matter for the citizenry to decide. However, no one need defer from taking a critical position in evaluating its policies and actions. Further, if one insists on indicting a country based on any premise, then the meterstick used to judge that country must be extended, first of all to one’s own country, and second, be extendable to all other countries without exception. Take the example of Jordan. Imperialists abstain from referring to Jordan as the Hashemite “regime,” which Britain fostered to allow for the installation of a Zionist state in Palestine. A similar imperialist impediment exists against calling the house of Windsor the monarchical regime, even though it descended from houses that conquered Scotland and Wales? Additionally, in terms of power as a family affair, familial lineages are now an entrenched trait in US politics: the influence of the Kennedys, the Bushes, and the Clintons in politics are recent examples. Where do we hear the protests against the power of such dynasties or their being dubbed as regimes transplanted in power roles through elections? If the explanation is that free elections led to that, then the validity of elections (as a process for attaining power for specific families) should be scrutinized and categorized. Moreover, because the validity of US “democracy” and US elections are questionable,4 is it not throwing rocks from a glasshouse when criticizing forms of government elsewhere? We understand that that not all governments are elected in a popular vote with multiple parties. But to assert that governments determined through US-style elections are more democratic is preposterous.5 This brings us to question of what has been learned from “regime change” wreaked by the United States and other western powers such as helping racists overthrow the socialist government in Libya, for example? The US Department of State in its “2016 Country Reports on Human Rights Practices” provides a rather damning example of what can result from “regime change”: The most serious human rights problems during the year resulted from the absence of effective governance, justice, and security institutions, and abuses and violations committed by armed groups affiliated with the government, its opponents, terrorists, and criminal groups. Consequences of the failure of the rule of law included arbitrary and unlawful killings and impunity for these crimes; civilian casualties in armed conflicts; killings of politicians and human rights defenders; torture and other cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment or punishment; and harsh and life-threatening conditions in detention and prison facilities. Other human rights abuses included arbitrary arrest and detention; lengthy pretrial detention; denial of fair public trial; an ineffective judicial system staffed by officials subject to intimidation; arbitrary interference with privacy and home; use of excessive force and other abuses in internal conflicts; limits on the freedoms of speech and press, including violence against and harassment of journalists; restrictions on freedom of religion; abuses of internally displaced persons, refugees, and migrants; corruption and lack of transparency in government; violence and social discrimination against women and ethnic and racial minorities, including foreign workers; trafficking in persons, including forced labor; legal and social discrimination based on sexual orientation; and violations of labor rights. Given the contemporary history in Libya, what would one predict for “regime change” in Syria? Discussion It is agreed that rhetoric can nonplus media consumers. Now, even though Maté uses the “regime” rhetoric, he nonetheless declares he is anti-“regime change.” This is a contradiction. For the record, we view Maté as an informed journalist worth listening to; but if we want to identify the conceptual dichotomies forced upon the use and misuse of such term, we need to dissect Maté’s ideological construct of regime and regime change If logical arguments matter, then it is one thing when the French once referred to the monarchic system prior to the French Revolution as the Ancien Régime—that when the term regime came into usage. However, it is something else when the West uses it as a means to express dubious political paradigms. The reason is simple: such expression comes with the implanted code/pretext for military intervention. In post-WWII imperialist practice, the moment a government of a given country gains the enmity of the United States (or Israel), it becomes a “regime.” For example, when Muammar Gaddafi was considered an enemy of the West, they called his government a regime. But when he gave up his advanced weapons programs and rudimentary equipment, the US and Britain refrained from using the word “regime” and started using the standard term: Libyan government. To show the change of heart of the West toward the Libyan leader, Tony Blair, a bona fide war criminal, went to dine with him in his tent. And when the Egyptian people were about to force the then incumbent ruler Hosni Mubarak to step down from power (in 2011), CNN anchor Anderson Cooper shouted from Cairo against the “dictator” Hosni Mubarak. Yes, Mubarak was a dictator. He was also an obedient stooge of the United States and Israel. But how did the United States and Israel call their stooge during the 32 years that preceded the Maidan al-Tahrir (Liberation Square) revolt? Former Israeli official Benjamin Ben-Eliezer called Egyptian president Hosni Mubarak “Israel’s greatest strategic treasure” and Haaretz’s editor-in-chief said Egypt under Mubarak was “Israel’s guard,” and the United States called Mubarak our “ally.” Another US oddity: the Al Saud family that is ruling Saudi Arabia, with its shuttered female population and head chopping meted out to malcontents, is a regime from top to bottom. When about 14,000 “royals” are placed in every crevice of power, then that power is the pure expression of a regime. And yet, we do not recall Western governments ever calling the Saudi family rule as regime. What is the mystery? There is no mystery. As stated, the term regime is all of the following: expedient, arbitrary, politicized, ideological, and to make sure, it is a tool of denigration for multiple objectives depending on who are the users. Thirty years ago, the Iraqi government of President Saddam Hussein called the Syrian government of President Hafez Assad a “regime.” Likewise, the Assad government (until the death of Hafez) has called the Iraqi government a “regime.” Interestingly, both Iraq and Syria called the Saudi ruling family a “regime.” Saudi Arabia (and the West) called the Iranian government the “mullah regime.” Today, US media have no qualms dubbing the Russian government as “the Putin Regime.” (It is easy to capitulate and wield the language in reverse. We, too, have called the G.W. Bush and the Obama administrations “regimes.”) Where do we go from here? What is a Régime? The notion that a government cannot be called regime because it is elected is a defective way to look at how things work. In the US, for example, the president is elected. Fine, but the entire administration is first appointed and then approved. Technically, therefore, the said administration is a specific regime convened within the framework of certain strictures. Consider this: no one elected Paul Wolfowitz, Richard Perle, and other Zionists to take decisions for war against Iraq. Yet, their influence in making decisions transcended the role of elected governance. Arguably, therefore, the US government is a particular regime that responds to special interests among its ruling elites. Consequently, when the United States calls any foreign government a “regime,” we immediately know that the appellation is dictated by the need of the imperialist system to appear as an expression of a “democratic government.” Meaning, while the US is a normal and democratic state, the other state is not. Recently, Paul Craig Roberts, an economist and former US Assistant Secretary of the Treasury under Ronald Reagan, joined the ideological skirmishes surrounding the use of the word regime. It is rare in US politics that elements belonging once to the Establishment acquire enough intellectual independence and honest lucid thinking to turn against it, and in the process, expose its making and who really rule it. Roberts is such a courageous element. However, in his article, “How Information Is Controlled by Washington, Israel, and Trolls, Leading to Our Destruction,” Roberts does not go all the way to investigate all aspects of a matter. He writes: I hold Israel and the Israel Lobby accountable, just as I held accountable the Reagan administration, the George H.W. Bush administration, the Clinton regime, the George W. Bush regime, the Obama regime, and the Trump regime. (I differentiate between administration and regime on the basis of whether the president actually had meaningful control over the government. If the president has some control, he has an administration.) [Emphasis added] Roberts tried to walk a very thin line between two concepts with different meanings and purposes: administration and regime. In short, his method to differentiate is critically flawed. He attributed the conceptual distinction to one factor: Control. The scheme does not work. Control, whether exercised in a “regime” setting or in an “administration” environment neither elucidates nor qualifies the structural quality of governance and its hierarchical order. For instance, it is known that Ronald Reagan, the governor and the president, was in the habit of delegating many if his responsibilities to others due to serious shortcomings (William E. Leuchtenburg, Professor Emeritus of History at the University of North Carolina, described Reagan with these words, “No one had ever entered the White House so grossly ill informed.”) This means, although Reagan might have had what it takes to appear as the one in charge, he lacked the expertise to run the complex system he was supposed to govern. However, both delegation of power and decision-making do not entail exercising control by those who give it because ultimately those who undertake such delegation are only theoretically responsible for it, while the delegator takes only nominal responsibility. Further, if the head of a given “regime” tightly controls the apparatuses of his government, would that be enough reason to qualify that regime as administration? On the other hand, even if Roberts meant to confine his distinction to the United States, his approach would not work either. Explanation: Roberts often uses the Deep State paradigm as the true pattern of power in the United States (we endorse this paradigm, too). But an altered reality, where patterns of power are preserved and repeated like clockwork, is the corollary of Deep State. Evidently, therefore, Roberts overlooked how the Deep State works. If this state is effectively in control of the US government, then that government is no longer an administration but a regime that carries the orders of that state. Considering that the American political system—since inception—responds positively to the financial and political interests and pressure by its capitalistic class, top oligarchs, and special interest groups, then all US administration are regimes—by concept and by fact—under the control of powerful circles. Curiously, is the Chinese government an administration or regime? When answering, we have to keep in mind the role of the Chinese Communist Party. Because this party appears to control the totality of the Chinese governmental policies and its economic plan, then do we have a regime? Would the Chinese government accept to be called a regime? Would any government accept to be labeled as a regime if such a term is heavily infused with derogatory attributes that could be used against them by aggressive states? Closing Remarks We resolutely consider a change of government imposed by foreign actors as an aggression and act of war. Definitively, it is illegal under the prevailing international law that imperialist states themselves co-wrote and endorsed. What constitutes a legitimate change of government? A change of government should be an expression of the will of a domestic population—be it through revolution, massive civil unrest, or peaceful transition of power. Consequently, we deem all states that are not installed by colonialist powers as having the inalienable right to be considered legitimate and viable for further development. Does voting confer legitimacy? Broadly, does western-style “democracy” imposed by the mass destruction of weaker nations give legitimacy to governments installed by aggressors? Why does the Vichy Regime installed by Hitler in France still evoke opprobrium but comparatively few criticize regimes installed by the United States in Afghanistan, Haiti, Iraq, and Libya? In the end, could such regimes ever evolve into a genuine democracy—assuming that we have settled on its acceptable definition and mechanisms? We submit that the answer is no. We view a government imposed by invaders as a means to satisfy the plans of the power that installed it, not the aspirations of the country’s people. Iraq is an example. The post-invasion Iraqi political system cannot be but a regime. When the US invaded Iraq in 2003, it dissolved its legitimate governing structures, the army, police force, ministries (except the oil ministry), banks, currency, and so on. Apart from geopolitical demarcation, the Iraqi state ceased to functionally exist including, of course, its political status. That is, we had no idea what it had become: anarchy-land, fiefdom, sect-land, republic, or just mere colony without face or name. And yet, the United States of George W. Bush went ahead and installed a “president” (Ghazi Ajil al-Yawar) for a shell republic. If the post-invasion political system was not a regime exemplar, then what is a regime? With all that, the United State never called the illegitimate and illegal order it imposed on Iraq (still in power today) with any label except the “Iraqi government” to convey the impression of normalcy. Since the dawn of history, no government has ever reached a theorized- or aspired-to perfection. Is such perfection possible? Societies and governance are an evolving process. In the example of Syria, the struggle of the Syrian people to liberate their land from French colonialism, to confront the installation of a militarized, expansionist Zionist state on its flanks and US plots to overthrow successive Syrian governments have all shaped political attitudes and considerations. Like most developing countries, the Syrian government has flaws. Shall we then accept the killing of over 350,000 Syrians and destruction of their cities in order to enlarge Israel, to allow Turkish intrusions against Syria’s territorial integrity and sovereignty, to provide passage for Qatari pipelines, to re-design the maps of the Arab world, and to turn Syria into an American and Israeli vassal? Consequent to these arguments, and when confronted with denominating the plethora of political systems existing today, our position is based on simple logic. First, we define any ruling entity of a country as government, and give the name administration to its political configuration. Second, we reserve the term regime to any entity—elected or not elected—that is ruled, directly or indirectly, by special interest groups, by clans, by families, by organizations, by personalities of dubious loyalty to the people, by lobbyists, by oligarchs, by ideologues, by militarists, and by servility to foreign governments. But in the first place, we reserve the term regime to any entity that declares itself above the laws of humanity, above the laws of nations, above criticism, and beyond moral accountability. To close, we believe clear-minded and critically thinking writers could take the lead in naming any government as “regime” if objective conditions—as explained (or further improved upon)—would support the designation. Again, a middle way exists: that we simply call the entity that rules a country as “government.” Ultimately, this could avoid the diatribe as to what a government is and how it differs from a regime. Having stated that, we do have serious problems when writers, using circulating clichés, uncritically follow the naming system promulgated by the US hyperpower. * Noam Chomsky, “Modern-Day American Imperialism: Middle East and Beyond.” * Walter LaFeber, Inevitable Revolutions: The United States in Central America, W. W. Norton & Company, 1993, p 19. * For a rebuttal see Robert Roth, What’s really happening in Syria (available for download here). * Noam Chomsky, who Maté admires (according to one bio), holds the US is not a genuine democracy. As for the validity of US elections, Greg Palast has been an outspoken critic of stolen elections. See his Billionaires & Ballot Bandits: How to Steal an Election in 9 Easy Steps. * See Arnold August, Cuba and Its Neighbours: Democracy in Motion (review). See also Wei Ling Chua, Democracy: What the West Can Learn from China (review). Both August and Chua provide compelling narratives on what approximates “democracy” and how favorably Cuba and China stack up compared to the United States. http://clubof.info/

0 notes