#Hupehsuchus nanchangensis

Text

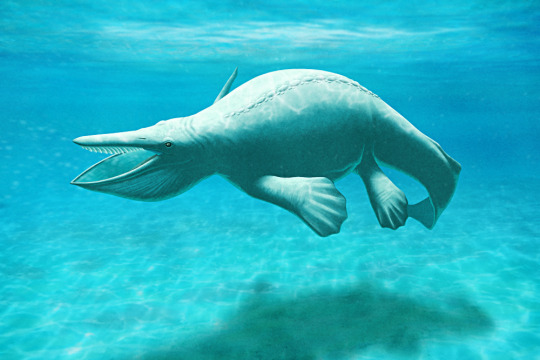

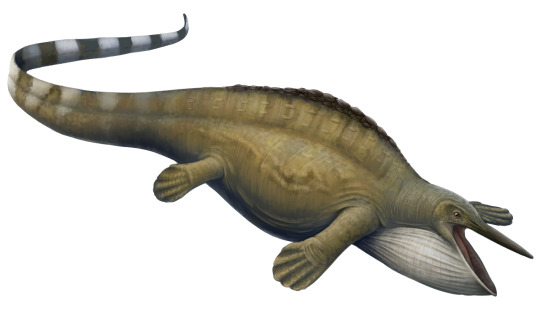

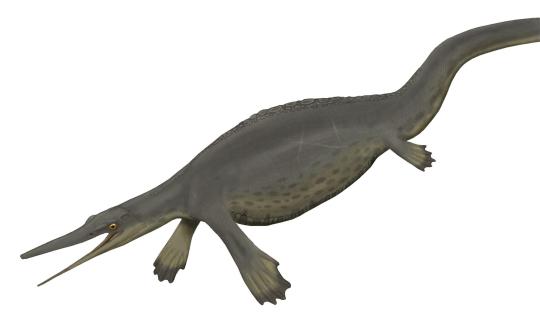

Hupehsuchians were small marine reptiles closely related to ichthyosaurs, known only from the Early Triassic of southwestern China about 249-247 million years ago. They had toothless snouts, streamlined bodies, paddle-like limbs, and long flattened tails, along with a unique pattern of armor along their backs made up of overlapping layers of bony osteoderms.

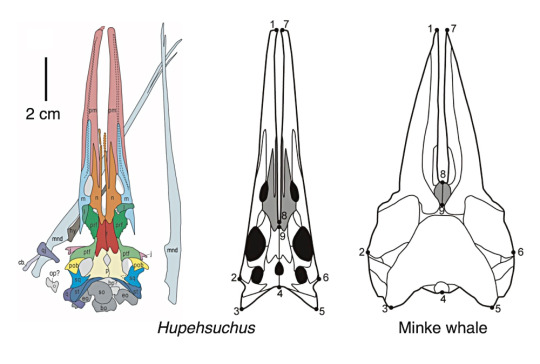

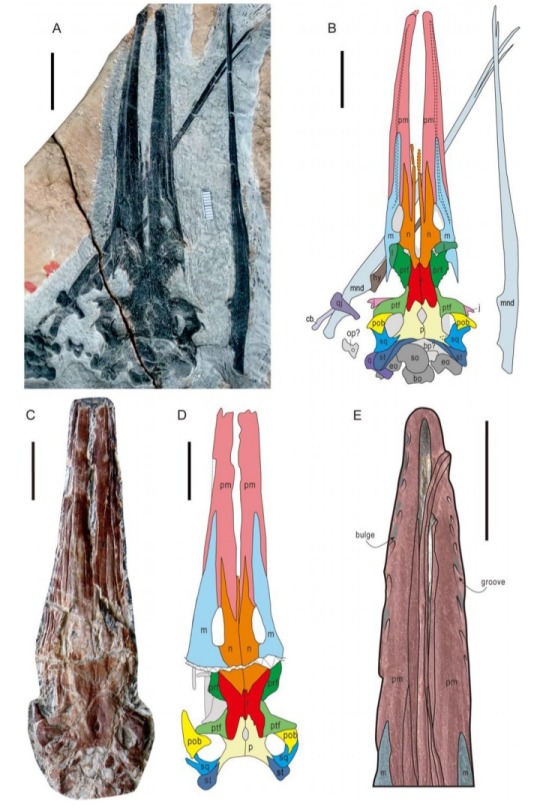

Hupehsuchus nanchangensis was a mid-sized member of the group, about 1m long (3'3"). Newly-discovered fossils of its skull show that its long flattened snout had a distinctive gap between the bones (similar to the platypus-like snout seen in its relative Eretmorhipis) with an overall shape surprisingly convergent with that of modern baleen whales – suggesting that this hupehsuchian may have been a similar sort of filter-feeder.

Hupehsuchus skull compared to a modern minke whale

[From fig 2 & fig 3 of Fang et al (2023). First filter feeding in the Early Triassic: cranial morphological convergence between Hupehsuchus and baleen whales. BMC Ecol Evo 23, 36. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12862-023-02143-9]

Grooves in the bones along the outer edges of its upper jaws may be evidence of filtering structures similar to baleen, although with no soft-tissue preservation we don't know exactly what this would have looked like. Its slender flexible lower jaws probably also supported a large expandable throat pouch, allowing it to filter plankton out of larger volumes of water.

———

NixIllustration.com | Tumblr | Patreon

#science illustration#paleontology#paleoart#palaeoblr#hupehsuchus#hupehsuchia#ichthyosauromorpha#reptile#marine reptile#art#triassic weirdos

596 notes

·

View notes

Text

First filter feeding in the Early Triassic: cranial morphological convergence between Hupehsuchus and baleen whales

Published 8th July 2023

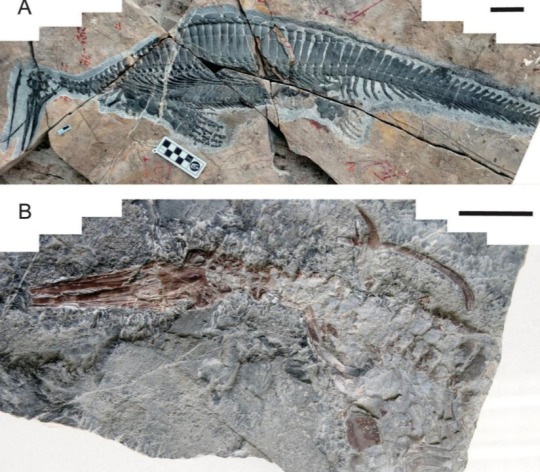

Two new specimens of the basal ichthyosauromorph Hupehsuchus nanchangensis are studied, revealing the first instance of filter feeding in ichthysauromorphs.

New specimens of Hupehsuchus nanchangensis

Morphological details of the Hupehsuchus nanchangensis skull

Source:

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Long before whales, pioneering marine reptile was a filter-feeder

Artist’s reconstruction shows the Triassic Period marine reptile Hupehsuchus nanchangensis, based on fossils unearthed in China’s Hubei Province. Hupehsuchus is believed to have been a filter-feeder, akin to some of today’s baleen whales.

| Photo Credit: Reuters

The blue whale and other baleen whales, the gentle giants of the sea, sift huge quantities of tiny prey from ocean water using a…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

An unusual ancient marine reptile may have gulped down tons of shrimplike prey using a feeding technique similar to one used by some modern whales. The reptile, named Hupehsuchus nanchangensis, lived in Earth's oceans between 247 million and 249 million years ago, during the early Triassic Period: https://rb.gy/npc0b

0 notes

Link

[ad_1] An unusual ancient marine reptile may have gulped down tons of shrimplike prey using a feeding technique similar to one used by some modern whales. The reptile, named Hupehsuchus nanchangensis, lived in Earth’s oceans between 247 million and 249 million years ago, during the early Triassic Period. Fossils of the reptile were first found in China in 1972. But researchers have struggled to understand the animal’s feeding behavior and lifestyle because none of the skulls were well preserved. Two newly discovered fossils unearthed from China’s Jialingjiang Formation in Hubei province include the nearly complete skeleton of one reptile and a large portion — from head to collarbone — of another. The discoveries enabled researchers to take a closer look at Hupehsuchus nanchangensis and determine that the reptile had a toothless snout and a small, narrow skull. Its lower jaw was loosely connected to the rest of the skull, which means the creature could expand its mouth — similar to how modern whales eat by filter feeding. A study detailing the findings was published Tuesday in the journal BMC Ecology and Evolution. “These were more complete than earlier finds and showed that the long snout was composed of unfused, straplike bones, with a long space between them running the length of the snout,” said study coauthor Long Cheng, professor at the Wuhan Center of China Geological Survey, in a statement. “This construction is only seen otherwise in modern baleen whales where the loose structure of the snout and lower jaws allows them to support a huge throat region that balloons out enormously as they swim forward, engulfing small prey.” Fossil evidence of filter feeding Researchers compared the Hupehsuchus skull with 130 modern skulls from a range of aquatic animals, which included 23 seal species, 14 crocodilians, 52 toothed whales, 25 birds, the platypus and 15 species of baleen whale. The study team discovered the creature had the most in common with the baleen whales. Modern bowhead and right whales are species that use filter-feeding techniques to eat, sifting material through plates of baleen as they swim with their mouths open near the ocean’s surface to take in large quantities of plankton or small crustaceans called krill. “Baleen is made from keratin, forming a soft and tough fibrous curtain dangling from the upper jaw in baleen whales,” according to the study. During filter feeding, the sturdy baleen plates entrap prey as water is forced out. But there hasn’t been much evidence in the fossil record for ancient reptiles using filter feeding, until now. While no actual evidence of baleen was found in the Hupehsuchus skull, the researchers noticed a series of grooves around the roof of the mouth where soft tissue may have helped with filter feeding. These structures are similar to what’s seen in baleen whales, which have strips of keratin instead of teeth. “Modern baleen whales have no teeth, unlike the toothed whales such as dolphins and orcas,” said study coauthor Li Tian, assistant researcher at the China University of Geosciences Wuhan, in a statement. “Baleen whales have grooves along the jaws to support curtains of baleen, long thin strips of keratin, the protein that makes hair, feathers and fingernails. Hupehsuchus had just the same grooves and notches along the edges of its jaws, and we suggest it had independently evolved into some form of baleen.” Hupehsuchus and evolutionary revelations Hupehsuchus had a rigid body that caused it to be a slow simmer, so the reptile likely expanded its throat while swimming to take in big gulps of water, straining out shrimplike prey from the early Triassic oceans. It’s possible that the marine reptile didn’t start out with this ability. Instead, the creature may have evolved over time, developing the adaptive physical traits that enabled filter feeding if the competition level for food was high, according to the study. The discovery is an example of what scientists call convergent evolution, where similar features evolve independently in different species. “We were amazed to discover these adaptations in such an early marine reptile,” said lead study author Zichen Fang at the Wuhan Center of China Geological Survey, in a statement. “The hupehsuchians were a unique group in China, close relatives of the ichthyosaurs, and known for 50 years, but their mode of life was not fully understood.” Whales evolved about 15 million years after dinosaurs went extinct at the end of the Cretaceous Period 66 million years ago. And it took about 17 million years for whales to evolve their filter-feeding adaptations, according to the study. But this same technique was quickly adapted, within about 5 million years, by marine reptiles that lived much earlier than whales. “The hupesuchians lived in the Early Triassic, about 248 million years ago, in China and they were part of a huge and rapid re-population of the oceans,” said study coauthor Michael Benton, professor of vertebrate palaeontology in the University of Bristol’s School of Earth Sciences, in a statement. “This was a time of turmoil, only three million years after the huge end-Permian mass extinction which had wiped out most of life. It’s been amazing to discover how fast these large marine reptiles came on the scene and entirely changed marine ecosystems of the time.” [ad_2]

0 notes

Text

Hupehsuchus nanchangensis

By Scott Reid

Etymology: Hubei crocodile

First Described By: Young & Dong, 1972

Classification: Biota, Archaea, Proteoarchaeota, Asgardarchaeota, Eukaryota, Neokaryota, Scotokaryota Opimoda, Podiata, Amorphea, Obazoa, Opisthokonta, Holozoa, Filozoa, Choanozoa, Animalia, Eumetazoa, Parahoxozoa, Bilateria, Nephrozoa, Deuterostomia, Chordata, Olfactores, Vertebrata, Craniata, Gnathostomata, Eugnathostomata, Osteichthyes, Sarcopterygii, Rhipidistia, Tetrapodomorpha, Eotetrapodiformes, Elpistostegalia, Stegocephalia, Tetrapoda, Reptiliomorpha, Amniota, Sauropsida, Eureptilia, Romeriida, Disapsida, Neodiapsida, Ichthyosauromorpha, Hupehsuchia, Hupehsuchidae

Referred Species: H. nanchangensis

Status: Extinct

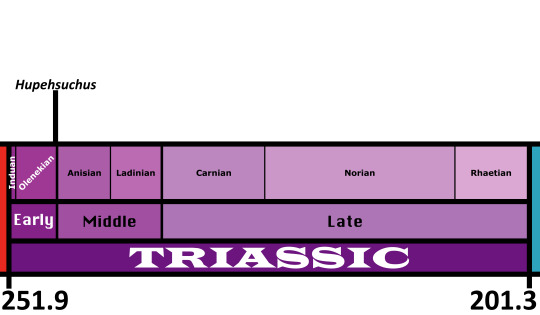

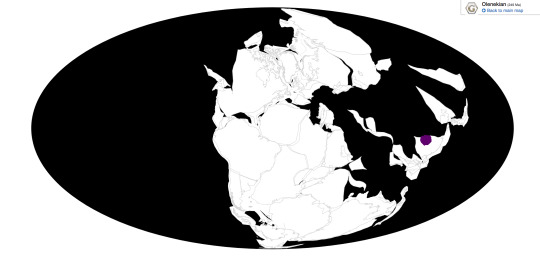

Time and Place: Between 248 to 247 million years ago, in the Olenekian of the Early Triassic

Hupehsuchus is known only from the Jialingjiang Formation in the Hubei Province of China.

Physical Description: At first glance, Hupehsuchus looks a lot like what you’d expect a primitive ichthyosaur to look like, and indeed they are related. Only around 1-2 metres (3-6 feet) long, its body is long and streamlined, with a long, pointed snout lacking teeth, limbs evolved into large rounded paddles, and a long flattened tail without a fluke. However, on closer inspection Hupehsuchus turns out to be much more bizarre.

Like other hupehsuchians, Hupehsuchus is heavily armoured with vertically layered rows of osteoderms running down its back over the vertebrae (you read that right, they’re on top of each other). These osteoderms interlock with each other, which may have stiffened the body and/or provided ballast. The vertebrae themselves have tall neural spines, giving Hupehsuchus an almost humpbacked appearance, and the neural spines appear to be made up of two separate pieces, one attached to the vertebra, the other seemingly attached to the osteoderms. Only hupehsuchians have vertebrae like that. Its body was probably compressed from side to side, taller than it was wide, and was only flexible around the hips and tail. The armour on its back is complemented by a robust, thick ribs that almost create a shield around its sides, and it even has heavily built, interlocking gastralia on its underside complete with another row of smaller osteoderms on the underside.

The skull of Hupehsuchus is also very unusual. The jaws are long, pointed, and the skull was seemingly quite broad and flat from above, resembling a duck’s bill. The lower jaws were incredibly thin and loosely attached to each other, and were probably capable of bending and bowing outwards like a pelican or baleen whale. The lower jaw may even have supported a large gular pouch, and large hyoid bones imply it had a powerful tongue. Furthermore, several parallel grooves in the upper jaw suggest the presence of a baleen-like structure in its mouth, making it even more uncannily similar to baleen whales. The neck, though, is relatively long and slender compared to a whale.

Diet: The bizarre adaptations of Hupehsuchus suggest it may have been a filter-feeder, sifting small particles and animals out of the water column or near the sea bed.

Behavior: Hupehsuchus was likely a lunge-feeder, in spite of its relatively long neck. The laterally compressed body and flexible hips and tail indicate that it swam by undulating through the water, likely lunging forwards suddenly through swarms of plankton and other small organisms to feed. The flexible jaws of Hupehsuchus imply that it engulfed large amounts of water as it fed, like whales, and would have strained it out through its filtering structures using its tongue.

Hupehsuchus almost certainly gave birth to live young, like ichthyosaurs. Partly because its anatomy was totally unsuited for crawling onto land to lay eggs, but also because one of the oldest ichthyosaurs, Chaohusaurus, is known to have given birth to its babies head-first, the opposite of the tail-first birth in other ichthyosaurs. Babies born head-first in water are at risk of drowning during birth, so this implies that live birth evolved in the ancestors of ichthyosaurs while they were still on land, which would mean that Hupehsuchus likely would have inherited this trait too.

Ecosystem: Hupehsuchus, and indeed all other hupehsuchians for that matter, are known only from a single locality in China. Here Hupehsuchus coexisted with its fellow hupehsuchians Nanchangosaurus, little short-necked Eohupehsuchus, the tubular Parahupehsuchus (I’m sensing a pattern here) and the truly bizarre platypus-faced Eretmorhipis (along with an undescribed polydactylous species!).

The diversity of hupehsuchians in this one habitat likely lead to diverse niche partitioning between them. Hupehsuchus was one of the largest, and seemingly occupied a more active lifestyle, lunge-feeding on organisms in the water. Nanchangosaurus had a similar skull to Hupehsuchus, and so may have had a similar diet, but it was smaller and had a body shape more suited for swimming along the sea bed. Parahupehsuchus was so heavily encased in armour that its body was practically a bony tube, and rather than round paddles it had pointed flippers, suggesting a different swimming style (for what, we don’t know). The bizarrest of them all, Eretmorhipis, may have specialised in grubbing blindly through the seabed, sensing prey with its bill like a platypus, possibly even at night.

The habitat is believed to have been a shallow lagoonal environment, perhaps sheltered from larger predators that could have preyed upon them, like giant nothosaurs. However, they nonetheless coexisted with the primitive ichthyosaur Chaohusaurus and two species of pachypleurosaur (sauropterygians related to nothosaurids), Keichousaurus and Hanosaurus, as well as an undescribed large sauropterygian 3-4 metres (10-13 feet) long. Strangely, no fish have been discovered in this formation, so it’s quite possible that the smaller hupehsuchians were the main food source for some of these larger marine reptiles (as evidenced by a bite taken out of one Eohupehsuchus paddle!). These conditions may have also prompted the strange dietary adaptations of the hupehsuchians, with no smaller fishes to eat, they specialised in eating tiny marine invertebrates and other plankton.

Other: Hupehsuchians are very mysterious marine reptiles, they are known from only one location in the whole world and from a very narrow range of time in the earliest Triassic. Hupehsuchus was once suggested to be a missing link between the ichthyosaurs and their as-yet-unknown terrestrial ancestors, although as more early ichthyosauromorphs have been discovered it is clear that is not the case, and that hupehsuchians are a bizarre offshoot of their own.

Hupehsuchus is part of a surprisingly diverse range of early-derived ichthyosauromorphs that lived in China during the Early Triassic, just a few million years after the Permian Mass Extinction, including the first proper ichthyopterygians and the peculiar (possibly amphibious) nasorostrans like Cartorhynchus. These marine reptiles were very quick to diversify in the wake after the extinction, as the strange filter-feeding lifestyle of Hupehsuchus testifies, quite the opposite of the predicted slow recovery for marine ecosystems. However, it remains a mystery why only the ichthyosaurs prevailed, and all the other strange and diverse ichthyosauromorphs like Hupehsuchus never even made it into the Middle Triassic. Perhaps they were just too strange and specialised even for the Triassic.

~ By Scott Reid

Sources under the Cut

Carrol, Robert L.; Dong, Z.-M. (1991). "Hupehsuchus, an enigmatic aquatic reptile from the Triassic of China, and the problem of establishing relationships". Philosophical Transactions: Biological Sciences. 331 (1260): 131–153.

Chen, X. H.; Motani, R.; Cheng, L.; Jiang, D. Y.; Rieppel, O. (2014). "A Carapace-Like Bony 'Body Tube' in an Early Triassic Marine Reptile and the Onset of Marine Tetrapod Predation". PLoS ONE. 9 (4): e94396.

Chen X. H., Motani, R., Cheng, L., Jiang, D. Y., Rieppel, O. (2014) “The Enigmatic Marine Reptile Nanchangosaurus from the Lower Triassic of Hubei, China and the Phylogenetic Affinities of Hupehsuchia”. PLoS ONE 9(7): e102361.

Chen, Xiao-hong; Motani, Ryosuke; Cheng, Long; Jiang, Da-yong; Rieppel, Olivier (May 27, 2015). "A New Specimen of Carroll's Mystery Hupehsuchian from the Lower Triassic of China". PLoS ONE. 10 (5): e0126024.

Cheng, L., Motani, R., Jiang, D.Y., Yan, C.B., Tintori, A. and Rieppel, O., (2019). “Early Triassic marine reptile representing the oldest record of unusually small eyes in reptiles indicating non-visual prey detection”. Scientific reports, 9(1), p.152.

Motani, R., Chen, X. H., Jiang, D. Y., Cheng, L., Tintori, A., Rieppel, O. (2015). “Lunge feeding in early marine reptiles and fast evolution of marine tetrapod feeding guilds”. Scientific reports. 5: 8900.

Wu, X.-C.; Li, Z.; Zhou, B.-C.; Dong, Z.-M. (2003). "A polydactylous amniote from the Triassic period". Nature. 426 (6966): 516.

Xiao-hong Chen; Ryosuke Motani; Long Cheng; Da-yong Jiang & Olivier Rieppel (2014). "A Small Short-Necked Hupehsuchian from the Lower Triassic of Hubei Province, China". PLoS ONE. 9 (12): e115244.

Xiao-hong Chen; Ryosuke Motani; Long Cheng; Da-yong Jiang; Olivier Rieppel (May 27, 2015). "A New Specimen of Carroll's Mystery Hupehsuchian from the Lower Triassic of China". PLoS ONE. 10 (5): e0126024.

#Hupehsuchus nanchangensis#Hupehsuchus#Triassic#Ichthyosaur#Reptile#Marine Reptile#Prehistoric Life#Palaeoblr#Paleontology#Prehistory#Triassic Madness#Triassic March Madness

551 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hupehsuchus nanchangensis

Art by: Smokeybjb, CC BY-SA 3.0

Name: Hupehsuchus nanchangensis

Name Meaning: Hubei crocodile (Hubei Province in China)

First Described: 1972

Described By: Young and Dong

Classification: Chordata, Tetrapoda, Reptilia, Hupehsuchia, Hupehsuchidae

Remember my post on Eretmorhipis, the weird and strange guy from the Early Triassic who was a part of a clade of marine reptiles that were closely related to ichthyosaurs? Well, we have another member of that clade for today’s entry! Hupehsuchus was also from the Early Triassic and was discovered in China and they too were pretty strange in their own right. They had a long toothless snout, long tail, and their limbs were like paddles, but not fully formed flippers as seen in later ichthyosaurs. Oh and let’s not forget, Hupehsuchus had armor on its back as well. There’s still a debate within the paleontological community on whether Hupehsuchus was even closely related to the ichthyosaurs or not. Some hypothesize that because this guy had extra bones within its hands instead of within its individual fingers, that the difference itself may possibly rule Hupehsuchus out in close relation to ichthyosaurs.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hupehsuchia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hupehsuchus

#Hupehsuchus#palaeoblr#paleontology#palaeontology#prehistoric#Mesozoic#ancient marine reptiles#Not a dinosaur#ichthyopterygia

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

My favorite part

Ichthyosauromorpha (Motani et al., 2015a) is an expansive group that includes the two clades Hupehsuchia (Young & Dong, 1972b) and Ichthyosauriformes. Hupehsuchia is a distinctive clade of Early Triassic marine reptiles so far known only from five southern Chinese species, namely Nanchangosaurus suni (Wang, 1959), Hupehsuchus nanchangensis (Carroll & Dong, 1991), Parahupehsuchus longus (Chen et al., 2014b), Eohupehsuchus brevicollis (Chen et al., 2014c) and Eretmorhipis carrolldongi (Chen et al., 2015).

0 notes

Link

[ad_1] An unusual ancient marine reptile may have gulped down tons of shrimplike prey using a feeding technique similar to one used by some modern whales. The reptile, named Hupehsuchus nanchangensis, lived in Earth’s oceans between 247 million and 249 million years ago, during the early Triassic Period. Fossils of the reptile were first found in China in 1972. But researchers have struggled to understand the animal’s feeding behavior and lifestyle because none of the skulls were well preserved. Two newly discovered fossils unearthed from China’s Jialingjiang Formation in Hubei province include the nearly complete skeleton of one reptile and a large portion — from head to collarbone — of another. The discoveries enabled researchers to take a closer look at Hupehsuchus nanchangensis and determine that the reptile had a toothless snout and a small, narrow skull. Its lower jaw was loosely connected to the rest of the skull, which means the creature could expand its mouth — similar to how modern whales eat by filter feeding. A study detailing the findings was published Tuesday in the journal BMC Ecology and Evolution. “These were more complete than earlier finds and showed that the long snout was composed of unfused, straplike bones, with a long space between them running the length of the snout,” said study coauthor Long Cheng, professor at the Wuhan Center of China Geological Survey, in a statement. “This construction is only seen otherwise in modern baleen whales where the loose structure of the snout and lower jaws allows them to support a huge throat region that balloons out enormously as they swim forward, engulfing small prey.” Fossil evidence of filter feeding Researchers compared the Hupehsuchus skull with 130 modern skulls from a range of aquatic animals, which included 23 seal species, 14 crocodilians, 52 toothed whales, 25 birds, the platypus and 15 species of baleen whale. The study team discovered the creature had the most in common with the baleen whales. Modern bowhead and right whales are species that use filter-feeding techniques to eat, sifting material through plates of baleen as they swim with their mouths open near the ocean’s surface to take in large quantities of plankton or small crustaceans called krill. “Baleen is made from keratin, forming a soft and tough fibrous curtain dangling from the upper jaw in baleen whales,” according to the study. During filter feeding, the sturdy baleen plates entrap prey as water is forced out. But there hasn’t been much evidence in the fossil record for ancient reptiles using filter feeding, until now. While no actual evidence of baleen was found in the Hupehsuchus skull, the researchers noticed a series of grooves around the roof of the mouth where soft tissue may have helped with filter feeding. These structures are similar to what’s seen in baleen whales, which have strips of keratin instead of teeth. “Modern baleen whales have no teeth, unlike the toothed whales such as dolphins and orcas,” said study coauthor Li Tian, assistant researcher at the China University of Geosciences Wuhan, in a statement. “Baleen whales have grooves along the jaws to support curtains of baleen, long thin strips of keratin, the protein that makes hair, feathers and fingernails. Hupehsuchus had just the same grooves and notches along the edges of its jaws, and we suggest it had independently evolved into some form of baleen.” Hupehsuchus and evolutionary revelations Hupehsuchus had a rigid body that caused it to be a slow simmer, so the reptile likely expanded its throat while swimming to take in big gulps of water, straining out shrimplike prey from the early Triassic oceans. It’s possible that the marine reptile didn’t start out with this ability. Instead, the creature may have evolved over time, developing the adaptive physical traits that enabled filter feeding if the competition level for food was high, according to the study. The discovery is an example of what scientists call convergent evolution, where similar features evolve independently in different species. “We were amazed to discover these adaptations in such an early marine reptile,” said lead study author Zichen Fang at the Wuhan Center of China Geological Survey, in a statement. “The hupehsuchians were a unique group in China, close relatives of the ichthyosaurs, and known for 50 years, but their mode of life was not fully understood.” Whales evolved about 15 million years after dinosaurs went extinct at the end of the Cretaceous Period 66 million years ago. And it took about 17 million years for whales to evolve their filter-feeding adaptations, according to the study. But this same technique was quickly adapted, within about 5 million years, by marine reptiles that lived much earlier than whales. “The hupesuchians lived in the Early Triassic, about 248 million years ago, in China and they were part of a huge and rapid re-population of the oceans,” said study coauthor Michael Benton, professor of vertebrate palaeontology in the University of Bristol’s School of Earth Sciences, in a statement. “This was a time of turmoil, only three million years after the huge end-Permian mass extinction which had wiped out most of life. It’s been amazing to discover how fast these large marine reptiles came on the scene and entirely changed marine ecosystems of the time.” [ad_2]

0 notes