#Ermo Colle

Text

domenica 11 settembre, a bazzano (parma): la poesia di milli graffi e giulia niccolai

domenica 11 settembre, a bazzano (parma): la poesia di milli graffi e giulia niccolai

in via Borgo, 2 – Bazzano 43024 Neviano degli Arduini, Emilia-Romagna

View On WordPress

#Adriano Engelbrecht#Barbara Anceschi#Bazzano#Daniela Rossi#Ermo Colle#Franca Rovigatti#Giulia Niccolai#La repubblica dei poeti#Laura Cingolani#lettura#letture#Milli Graffi#Museo Uomo Ambiente#poesia#reading#ricerca letteraria

0 notes

Text

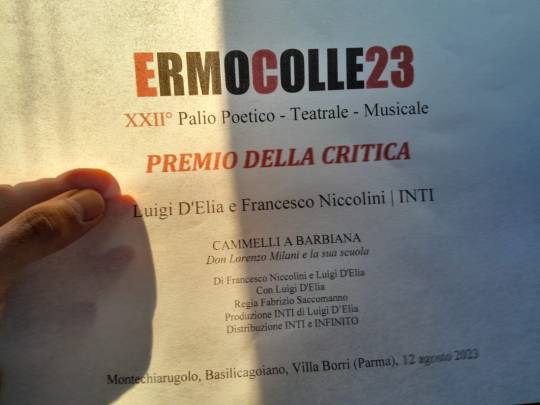

CAMMELLI A BARBIANA, Don Lorenzo Milani e la sua scuola

ha vinto il Premio della critica alla XXII edizione del Palio Ermo Colle, Parma (ex-equo con Acquasantissima di Fabrizio Pugliese).

Il premio è stato consegnato lo scorso 12 agosto a Villa Borri, Montechiarugolo.

La giuria era composta da Elisa Cuppini, Roberta Gatti, Silvio Malacarne, Valeria Ottolenghi, Sandra Soncini.

Le motivazioni della giuria > https://www.ermocolle.eu/

#luigidelia#teatro#cammelliabarbiana#donmilani#barbiana#narrazione#scuola#francesconiccolini#palioermocolle#ermocolle

2 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

ITALIAN POEMS- LEARN ITALIAN with poetry - L'INFINITO di Giacomo Leopardi 🖋

ITALIAN POEMS- LEARN ITALIAN with poetry - L'INFINITO di Giacomo Leopardi 🖋

https://youtu.be/jXoSfOh6NT0

Leopardi definisce idilli sei delle sue poesie in endecasillabi sciolti,tutte composte tra il 1819 e il 1821, tra cui L’infinito. L’idillio leopardiano non è però la descrizione di un paesaggionaturale, come era invece nella poesia di epoca classica, ma la evocazione di particolari stati d’animo e sensazioni del poeta.In questo idillio, composto nel 1819, Leopardi prende spunto dalpaesaggio di Recanati, contemplato da un colle solitario, per raccontareun’avventura dell’anima: un viaggio fantastico nell’immensità, in cui ilpoeta si perde dolcemente.Sulla cima di una collinetta vicino a Recanati, il poeta sta seduto di fronte a una siepe, che impedisce al suo sguardo di vedere l’orizzonte. Ma proprio questo ostacolo alla vista fa scattare in lui l’immaginazione, che lo trasporta in spazi sconfinati e immensi. Il fruscio del vento tra gli alberi loriporta alla realtà, ma al tempo stesso gli ricorda il passare del tempo e gli suggerisce il pensiero dell’eternità. Ormai distaccato dalla dimensione della vita quotidiana, non senza timore il poeta si abbandona all’abbraccio dell’infinito. Il raggiungimento dell’infinito, a cui l’anima di ogni uomo aspira, porta con sé un’intensa gioia, ma anche un senso di indefinito sgomento.

L'INFINITO

Sempre caro mi fu quest’ermo colle1,

e questa siepe, che da tanta partedell’ultimo orizzonte il guardo esclude2.

Ma sedendo e mirando3,

interminatispazi di là da quella, e sovrumani

silenzi, e profondissima quiete

io nel pensier mi fingo4;

ove per pocoil cor non si spaura5.

E come6 il vento odo stormir7 tra queste piante, io quello10

infinito silenzio a questa voce vo comparando8:

e mi sovvien l’eterno,e le morte stagioni, e la presente e viva, e il suon di lei9. Così tra questaimmensità s’annega il pensier mio10:15

e il naufragar m’è dolce in questo mare11.

1 ermo colle: colle solitario [è il Monte Tabor, aRecanati].2 da tanta parte… esclude: che sottrae allo sguardo una gran parte dell’estremo orizzonte.3 mirando: guardando.4 interminati… mi fingo: oltre quella [siepe] immagino (mi fingo) nella mia mente (nel pensier) spazi infiniti (interminati), silenzi inconcepibili per l’uomo, e una pace profondissima.5 ove… si spaura: dove il mio cuore quasi si spaventa.6 come: quando.7 stormir: produrre un rumore leggero, un fruscio [di fronde e foglie agitate dal vento].8 a questa… comparando: la metto a confronto con questo suono [del vento].9 mi sovvien… di lei: mi viene in mente l’eternità, il tempo passato (le morte stagioni), e il tempo presentecon i suoi (di lei) rumori (suon).10 tra questa… il pensier mio: nell’immensità dello spazio e del tempo il mio pensiero si immerge.11 e... questo mare: e perdermi (naufragar) in questo mare [dell’infinito] è per me dolcissimo.

LE TRADUZIONI DELL'INFINITOInfinity

Fond I was ever of this lonely hill,And of this edge, that from my view concealsThe farthest limit of the firmament.But, sitting here and gazing, I can feign,Far and beyond it, still unbounded space,And an unearthly silence, and the deepestQuietude where my very heart is nearlyFrightened. And as this moment I perceiveThe wind around me rustling through these trees,To that unending silence soon I likenThe passing of its voice: eternityI so recall, and all the seasons dead,And with this lively stir the present one.Founders in such immensity my mind,And drowning in this sea is sweet to me.

VERSIONE POETICA DI JOSEPH TUSIANI

0 notes

Link

0 notes

Text

La mia ex vota Salvini(si, lamia ex. N. Donna, lesbica e giovane adulta appena alla sua seconda votazione). Il marito di mia zia, uomo calabrese sposato con una siciliana con una cognata (mia madre) colombiana e una nipote (la moglie di mio cugino) marocchina, è candidato come consigliere comunale con la Lega. Due settimane fa nella predica, il mio pastore(sono protestante), uomo brasiliano e alla guida di una chiesa battista (che per i veri e fieri cattolici ignoranti è lo stesso che i testimoni di geova) ha praticamente consigliato di votare Lega, la Meloni o chiunque fosse al congresso della famiglia naturale con i fetini portachiavi comunque. Mia madre (ricordo donna nera sud America) ha espresso simpatie per Salvini!!!!! E se alla luce di questo, qualcuno, ha ancora il coraggio di chiedermi perché disprezzo tanto l'umanità, lo prendo a sberle con la costituzione.

#diariodibordo#diaridibordo#lega#salvini#merda#la tristezza#datemi un ermo colle da cui vomitare l'infinito

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Discussion and Translation of Leopardi’s “L’infinito.”

Here is Leopardi’s “L’infinito.” After a discussion of the poem’s structure and drama follows my translation. If you don’t know Italian, you may still enjoy the discussion; if you do know Italian, and care to comment, I’d like particularly to know if you think my observations justify my having translated sovvien as “to my rescue come.”

Sempre caro mi fu quest’ermo colle,

e questa siepe, che da tanta parte

dell’ultimo orizzonte il guardo esclude.

Ma sedendo e mirando, interminati

spazi di là da quella, e sovrumani

silenzi, e profondissima quiete

io nel pensier mi fingo; ove per poco

il cor non si spaura. E come il vento

odo stormir tra queste piante, io quello

infinito silenzio a questa voce

vo comparando: e mi sovvien l’eterno,

e le morte stagioni, e la presente

e viva, e il suon di lei. Così tra questa

immensità s’annega il pensier mio:

e il naufragar m’è dolce in questo mare.

Always dear to me was this hermit hill, and this hedgerow, which from so many sides closes the view off from the last horizon. But sitting and gazing, interminable spaces from here to there, and superhuman silences, and profoundest quiet I imagine in my mind, to the point where my heart almost jumps in fear. And as I listen to the wind storming among these growths, that infinite silence to this voice I go comparing; and come to mind the eternal, the dead seasons, and the present one and living, and its sound. So amid this immensity drowns my thought: and shipwreck is sweet to me in this sea.

The poem’s four sentences make for its four parts: (i) Sempre…esclude; (ii) Ma sedendo…si spaura; (iii) E come…suon di lei; (iv) Così…mare. The first and fourth parts are contraries indicated by the contrast of caro to dolce; they bracket the contraries of the second and third parts indicated by il pensier… il pensier; the il cor…at the close of part two contrasts with an il cor implicit in the first line’s caro and another in the last line’s dolce; you could say that in that cor-cor-cor a three-part structure overlays the four-part one, the character arc at work in the four-act plot; and the play in movement unfolding in questo (masculine form of “this”) in line one, questa in two, quella (feminine form of “that”) in five, queste (feminine plural) and quello in nine, questa in ten, questa in thirteen, and questo in fifteen is a passage from an initial station through a restless back and forth to a final settling; they bind the arc to the plot.

Three oddities require recognition of these structures so that one can grasp the spiritual drama.

The first is the fact that in sempre caro mi fu, sempre, “always,” does not have the sense of everlastingly, but continuously or continually thus far; thus fu does not mean has been, but was. So, for instance, when a person who has played an important part in our life dies, we do not say, “He has always been good to me,” for that leaves open the possibility that his kindness might in future cease, but rather, “He was always good to me.” We may say that the moment he dies, or the moment we hear that he is dead. This means that, when Giacomo—let’s call the speaker in the poem—begins to speak, he shows himself to be aware that an epoch in his life has ended and with its death nothing in its past existence is at his disposal for any future.

The second is that the questo and questa of the first two lines indicate that Giacomo is, at this very moment, on that hilltop and at this very moment is looking at that hedgerow, just as the questa of line thirteen and the questo of line fifteen indicate that at this very moment it is in this immensity and at this very moment in this sea that he finds himself; since the ermo—from the Greek erêmos, “desolate, lonely,” from which comes our word “hermit”—indicates that he is alone, in the poem he is not recollecting an experience, but narrating his own experience to himself. Of course, that is not quite right: obviously if Leopardi had chosen to write in the third person the poem would lack all force; and just as obviously in the moment in which we pass from perplexity to epiphany our experience of the passage and of the climax is wordless, so there is no way for Leopardi to represent Giacomo’s experience except in the odd self-narration; the thing is, all that happens is happening now.

I insist on pointing this out because only so can I make clear that the opening sentence, the first part, does indicate the close of one epoch in Giacomo’s life with himself in relation to the hilltop, and that, with the second part’s opening ma, literally “but,” he indicates his displacement into the first moment of the new epoch whose relation to his heart is indeterminate.

It seems to me that the oddity of the narration as it unfolds in the four-part dramatic structure with the three-part character arc shows that in reading we follow an unfolding drama in which Giacomo finds himself perplexed at the death of a source of contentment, gets himself in trouble, makes an effort to get himself out of trouble, gets help, sees his adversary vanquished, and feels a new contentment from a new source.

Third, since Giacomo tells us that, for the most part, the hedgerow blocks his view of the horizon, and since in the second part he tells us that he is sitting and gazing, but that he is also imagining spaces, he cannot actually be looking at what portion of the horizon the gaps in the hedgerow do allow one to see—if he were, there would be no point in mentioning the hedgerows; and if it is beyond because starting from the hedgerows that he is imagining spaces, then he cannot be sitting in front of the hedgerows looking, for then, in order to imagine spaces beyond, he would have to start from the visible portion of horizon.

(I have found two types of photographs: one looking up at the hedgerows atop a wall that stands on some deck on Mount Tabor from which the photograph is taken, so that we are shown the rising walls and the capping hedgerow:

and a view from some spot on Mount Tabor, presumably, but that does not include the hedges, from which one can see Recanati, the town in which Leopardi was born and grew up, sprawling to a perfectly visible horizon:

There may be photographs taken from within the hedgerow so that you can see how much it blocks the horizon from view, but I have yet to find them.)

It would seem, then, that Giacomo is sitting on something in the space on the hilltop that the hedgerow encloses with his back to the hedgerows, and just staring into space, absorbed in the vision he conjures for himself of space and silence in his thought.

The second part ends with the experience of fright, reminiscent of Pascal’s le silence éternel de ces espaces infinis m’effraie—but only reminiscent: where Pascal calls his spaces merely infinite, Giacomo says that they are interminati—that they don’t come to an end. That implies that in his mind he is travelling along those spaces and at some point realizes that they are never going to come to an end; that’s why he says, not that they frighten him, but that in imagining these things in his thought he does so to the point where his heart almost suffers a spavento, no simple fright, but a jolt or spasm.

The third part begins with a return to the earthly present—he hears the storming wind, and begins to compare the endless silence to the noise; compare why? My surmise is that he needs help against the lingering dismay from that silence and endlessness—note well that it is THAT silence, that the silence is distant from him, but it is still close because, of all the thats that he can contrast to the this of THIS noise, the reality that is closest to him (sight will not help him) and perhaps standing between him and that silence, he chooses the that of that silence. Compare how? With respect to what is endless in THIS noise; why say that that is the respect? Well, what happens as he starts comparing?

The eternal and the precession of dead seasons—stagioni is not a synecdoche for eras or epochs, since eras and epochs don’t have a sound—and the living present and the sound of the present come to him; they themselves, not the thought of them, come to him; but again, what makes me think that?

You’ve had that experience when, after so many years, you return to your childhood home or haunts, and in their presence you feel the intervening years slough away—you feel this in your body.

There’s another experience you’ve had; you look at a photograph of a size and shape and cut that indicates it is from a long dead epoch of photography: it is a photograph of unknown people dressed in fashions that indicate they belong to a long dead epoch; but neither set of epochal signs suffices to indicate any determinate temporal route from them to you; but you are not disoriented—you feel a quiet awe at the strangeness of time. It’s a feeling that comes over you and you feel this in your appetite—you cannot get enough of looking at the image—and you cannot get over the uncanniness of which you are in awe—the feeling takes hold of you; you feel it in and with your simple existence as a temporal being. (In Germany: Year Zero, Godard has someone say that, according to the Talmud, the first men who realized they were in time smiled.)

Yet another: usually we are immersed in the present and so do not think about it as present, but sometimes, when all claims are lifted from us, we feel the presentness of the present—that’s why we call a vacation a vacation, that is, a time that is vacated of claims on us to make use of something past in the present for the sake of some future. That’s why we like that moment in The Shawshank Redemption when after their labors the men sit on the rooftop drinking beer. You feel this in the suspension of all passions of concern and care, in the lifting of their weight.

As to the sound of the present, the first thing to be said is this: Only two of our senses have horizons, sight and hearing. Sight has a horizon only in front of us and only across the field of our vision, but in our hearing we relate to ourselves as the center of several horizons that circumvault us above and below and every which way roundabout variously according to the distance from which the sound can travel to us; it is because sounds do have distances and directions and never fill the air entirely that we can hear silences and quiet, meaning we can tell where they are, how far they reach, and can distinguish them with respect to the things not making noise, so that we relate to silences and quiet as having a manifold of circumvaulting horizons, too.

And each season sounds as no other season sounds, and each season can present itself as a whole in one moment of characteristic sounds: the whole of summer is presented in one moment of a buzzing past of something near your head, somewhat far off behind you the sound of children screaming in play, further off still but in front of you the sound of a tractor’s sputtering roar, from below the splash of a stone your little brother has tossed into the lake that spreads from the foot of the hill on which you sit, and high above an airplane passing and its drone rippling down through the heavens just to you.

So the third part ends with a sloughing of years, a boundless appetite for what is incalculably near and far in time that holds you fast, all weight lifted from the present, and the presentation of the presentness of the present in the several horizons in its sound; what happens next?

Giacomo finds himself in a new vastness now—the vastness that is the eternity in which season upon season presents itself then passes into eternity, and in this new vastness his thought drowns—poor thing! Requiescat in pace! Now what he feels in his heart is the sweetness of the event in and by which his thought drowns, a shipwreck. What shipwreck of what ship broken against what?

Pascal says that you cannot not bet—you are already embarked. I always point out to my students that the term embarked implies that in existing we are not on a journey, but on a voyage; I ask them to explain to me the difference between a journey and a voyage—they seldom can, so I point out that, on a journey, before arriving at your destination you can always stop; not possible at sea. But though death is necessarily the final port of our voyage in existence, and Pascal depends upon that necessity to convince us that we cannot not bet, death is not a misadventure, as is a shipwreck, and anyway, Giacomo says nothing to indicate that he experiences any sort of death—only his thought drowns; so again, what shipwreck of what ship broken against what?

My translation:

Always sweet to me was this sequestered

Hilltop, and this hedgerow which, turn what side

I will, shuts the last horizon from my view.

Sitting now and gazing, in my thought I

Conjure, spilt from that hedgerow, spaces

Never-ending, and silences dealt past all

Things human, and hush abyssal, so my heart

Leaps nigh beside itself in fright. But as I hear

The wind thrashing through these growths, I try

Comparing that boundless silence with this

Din: and to my rescue come the eternal,

And the dead seasons, and the present one

All living, and the sound of it. Thus

Into this vastness drowns my thought:

And easeful to me’s shipwreck on this sea.

Italians consider this poem of Leopardi’s to be the most beautiful in the language; here’s roughly why.

The poem consists of four sentences unfolding in fifteen lines with ten enjambements—a line ending that does not coincide with the syntactical end of a clause, so that in reading one does not pause between the end of that line and the beginning of the next, because the words form one unbreakable syntactical unit; the syntax includes several displacements of the semantic head of the sentence to its syntactical end, inversions of the usual order of adjectives and the nouns they qualify; a complex and gorgeously understated play of assonance and alliteration; and its matter involves things vested with an uncanny, muted splendor; think of Turner.

When I first thought of translating Leopardi’s poem a few weeks ago, I looked for recitations on YouTube. What I found surprised me.

Time after time the actors seemed to think that, because of the poem’s beauty, their voice had to flow in honied languid undulations from Sempre to questo mare; the absolute worst was a reciter who pronounced each word with an orgasmic gurgle and each stressed word in a clause with a giddy roller-coaster flip in which down springs and up plunges. The poem is beautiful, yes; but Giacomo’s experience is not an experience of beauty—not like, say, Byron’s “She walks in beauty” is a beautiful poem about the experience of beauty.

But the relative worst was Germano Bonaveri. Bonaveri is quite handsome: he’s swarthy, wears a ring in his right ear, has thick black eyebrows over dark hooded eyes, has a close-cropped feathery white beard and a thick black moustache—the look, I think, that casting directors want actors to have when they are to exhibit the sort of lush gypsy or pirate virility that makes women fall easily backward in thought onto a cloud of willingness, thighs spread in ready waiting high humidity. I mention this because Bonaveri’s face fills the screen but is shown only from just below his brow at his eyebrows, just a little past his right ear lobe, and not quite down to his chin; in reading, Bonaveri keeps his lips puckered right at the round knob head of the microphone, and you can’t help but note every dip of his head and every time he lifts his brows or holds his eyelids closed in that interlude of voluptuously ineffectual pulling of the hood of the upper lid against the tarrying why-can’t-this-last hermetic clamping of the upper lid’s lip to the lip of the lower that signifies o-what-sweetness a-waft in the mind; in his recitation he caresses each word and phrase in bursts of urgency according to the sense, so that when he stops for each caesura you hear the silence as you see a lace curtain billowing down nearly to the sill only then to billow up backwards into the room: it’s like he’s performing cunnilingus.

I thought it was the relative worst because Bonaveri does use a certain restraint and understatement proper to the poem, but since “L’infinito” isn’t a love poem, the restraint and understatement should not be erotic; he hasn’t taken on the persona of Giacomo to give it life.

I think the poem should be read with restraint and understatement because of what seems to me that movement from perplexity at the sudden loss of a long-standing enjoyment to fear to rescue to a new satisfaction or contentment. Leopardi isn’t speaking to us as beings who like to climb mountains and glory in the earth’s beauty, but in the persona of Giacomo represents us to ourselves as beings who can find ourselves, in some innocent contemplation, suddenly caught in the toils of something that threatens to undo us, and even if we escape, find we need something to undo our ever having been caught.

The one reader who recites with the necessary restraint is Giuseppe Cederna; characteristically, it seems that most of those who have commented on it hate it.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

1 note

·

View note

Text

La città di Mondavio e l'itinerario della bellezza nella provincia di Pesaro Urbino

La città di Mondavio e l’itinerario della bellezza nella provincia di Pesaro Urbino

Ci sono paesaggi che ad ammirarli dall’alto di un ermo colle rimandano a una sensazione di pace e di serenità, stati d’animo che fanno bene al cuore e all’animo.

Continue reading

View On WordPress

0 notes

Link

0 notes

Link

0 notes

Link

0 notes

Text

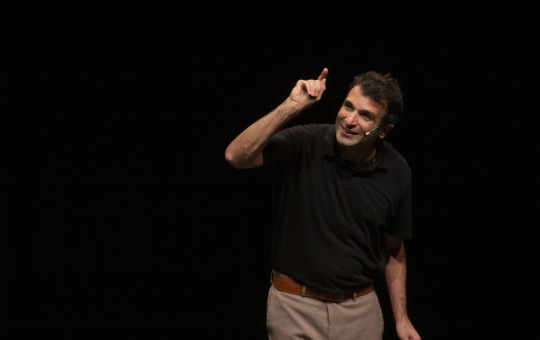

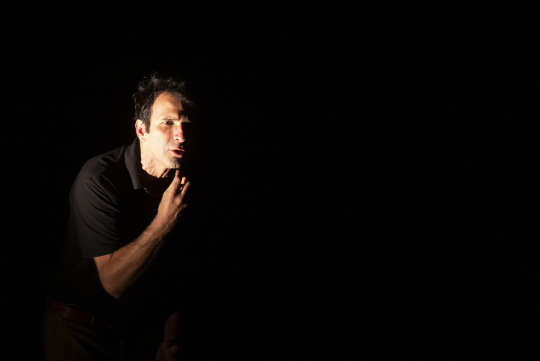

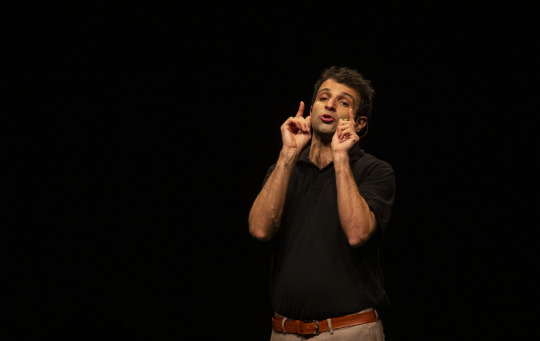

Da Parma, dal premio Ermo Colle, arriva ancora una recensione per Cammelli a Barbiana. La firma è quella prestigiosa di Valeria Ottolenghi. (visto a Felino lo scorso 31 luglio)

"D'Elia è attore straordinario: con Cammelli a Barbiana crea una sorta d'incanto, un intenso coinvolgimento mentre si ascoltano i frammenti delle lettere (…) Un'intrepretazione complessa, con continui passaggi dalla narrazione all'immedesimazione: bravissimo!"

Articolo completo tra le foto.

2 notes

·

View notes

Link

0 notes

Link

0 notes

Photo

Sempre caro mi fu #leopardi #giacomoleopardi #infinito #colledellinfinito #recanati #marche #huaweip30lite #nofilter #agosto #estate (presso Sull Ermo Colle) https://www.instagram.com/p/CD-7LcgKu1w/?igshid=1rah6pg41mei

#leopardi#giacomoleopardi#infinito#colledellinfinito#recanati#marche#huaweip30lite#nofilter#agosto#estate

0 notes

Photo

Sempre caro mi fu quest ermo colle (presso Recanati Città dell'Infinito) https://www.instagram.com/p/CD1rWBVoYvO/?igshid=1vpd86mw044dq

0 notes