#Dakota Men Killed | Mankato

Text

Native Tribe To Get Back Land 160 Years After Largest Mass Hanging In US History

Upper Sioux Agency state park in Minnesota, where bodies of those killed after US-Dakota war are buried, to be transferred

— Associated Press | Sunday 3 September, 2023

The Upper Sioux Agency State Park near Granite Falls, Minnesota. Photograph: Trisha Ahmed/AP

Golden prairies and winding rivers of a Minnesota state park also hold the secret burial sites of Dakota people who died as the United States failed to fulfill treaties with Native Americans more than a century ago. Now their descendants are getting the land back.

The state is taking the rare step of transferring the park with a fraught history back to a Dakota tribe, trying to make amends for events that led to a war and the largest mass hanging in US history.

“It’s a place of holocaust. Our people starved to death there,” said Kevin Jensvold, chairman of the Upper Sioux Community, a small tribe with about 550 members just outside the park.

The Upper Sioux Agency state park in south-western Minnesota spans a little more than 2 sq miles (about 5 sq km) and includes the ruins of a federal complex where officers withheld supplies from Dakota people, leading to starvation and deaths.

Decades of tension exploded into the US-Dakota war of 1862 between settler-colonists and a faction of Dakota people, according to the Minnesota Historical Society. After the US won the war, the government hanged more people than in any other execution in the nation. A memorial honors the 38 Dakota men killed in Mankato, 110 miles (177km) from the park.

Jensvold said he has spent 18 years asking the state to return the park to his tribe. He began when a tribal elder told him it was unjust Dakota people at the time needed to pay a state fee for each visit to the graves of their ancestors there.

Native American tribe in Maine buys back Island taken 160 years ago! The Passamaquoddy’s purchase of Pine Island for $355,000 is the latest in a series of successful ‘land back’ campaigns for indigenous people in the US. Pine Island. Photograph: Courtesy the writer, Alice Hutton. Friday 4 June, 2021

Lawmakers finally authorized the transfer this year when Democrats took control of the house, senate and governor’s office for the first time in nearly a decade, said State Senator Mary Kunesh, a Democrat and descendant of the Standing Rock Nation.

Tribes speaking out about injustices have helped more people understand how lands were taken and treaties were often not upheld, Kunesh said, adding that people seem more interested now in “doing the right thing and getting lands back to tribes”.

But the transfer also would mean fewer tourists and less money for the nearby town of Granite Falls, said Mayor Dave Smiglewski. He and other opponents say recreational land and historic sites should be publicly owned, not given to a few people, though lawmakers set aside funding for the state to buy land to replace losses in the transfer.

The park is dotted with hiking trails, campsites, picnic tables, fishing access, snowmobiling and horseback riding routes and tall grasses with wildflowers that dance in hot summer winds.

“People that want to make things right with history’s injustices are compelled often to support action like this without thinking about other ramifications,” Smiglewski said. “A number, if not a majority, of state parks have similar sacred meaning to Indigenous tribes. So where would it stop?”

In recent years, some tribes in the US, Canada and Australia have gotten their rights to ancestral lands restored with the growth of the Land Back movement, which seeks to return lands to Indigenous people.

‘It’s a powerful feeling’: the Indigenous American tribe helping to bring back buffalo 🦬! Matt Krupnick in Wolakota Buffalo Range, South Dakota. Sunday 20 February, 2022. The Wolakota Buffalo Range in South Dakota has swelled to 750 bison with a goal of reaching 1,200. Photograph: Matt Krupnick

A National Park has never been transferred from the US government to a tribal nation, but a handful are Co-managed with Tribes, including Grand Portage National Nonument in northern Minnesota, Canyon de Chelly National Monument in Arizona and Glacier Bay National Park in Alaska, Jenny Anzelmo-Sarles of the National Park Service said.

This will be the first time Minnesota transfers a state park to a Native American community, said Ann Pierce, director of Minnesota State Parks and trails at the natural resources department.

Minnesota’s transfer, expected to take years to finish, is tucked into several large bills covering several issues. The bills allocate more than $6m to facilitate the transfer by 2033. The money can be used to buy land with recreational opportunities and pay for appraisals, road and bridge demolition and other engineering.

Chris Swedzinski and Gary Dahms, the Republican lawmakers representing the portion of the state encompassing the park, declined through their aides to comment about their stances on the transfer.

— The Guardian USA

#Minnesota#U.S. 🇺🇸 News#World 🌎 News#Native Tribes#Land Buy Back#The Upper Sioux Agency State Park#Burial Sites of Dakota People#United States 🇺🇸 | Failed Treaties#Native Americans#Kevin Jensvold | Upper Sioux Community#US-Dakota War of 1862#Dakota Men Killed | Mankato#Minnesota Historical Society#State Senator | Mary Kunesh | Democrat | Descendant | Standing Rock Nation#Granite Falls#Mayor Dave Smiglewski#US 🇺🇸 | Canada 🍁 🇨🇦 | Australia 🇦🇺#Ancestral Lands Restored#Land Back Movements#Grand Portage National Nonument#Canyon de Chelly National Monument#Glacier Bay National Park#Ann Pierce | Minnesota State Parks#Chris Swedzinski | Gary Dahms | Republican Lawmakers

259 notes

·

View notes

Quote

The state is taking the rare step of transferring the park with a fraught history back to a Dakota tribe, trying to make amends for events that led to a war and the largest mass hanging in US history.

“It’s a place of holocaust. Our people starved to death there,” said Kevin Jensvold, chairman of the Upper Sioux Community, a small tribe with about 550 members just outside the park.

The Upper Sioux Agency state park in south-western Minnesota spans a little more than 2 sq miles (about 5 sq km) and includes the ruins of a federal complex where officers withheld supplies from Dakota people, leading to starvation and deaths.

Decades of tension exploded into the US-Dakota war of 1862 between settler-colonists and a faction of Dakota people, according to the Minnesota Historical Society. After the US won the war, the government hanged more people than in any other execution in the nation. A memorial honors the 38 Dakota men killed in Mankato, 110 miles (177km) from the park.

Jensvold said he has spent 18 years asking the state to return the park to his tribe. He began when a tribal elder told him it was unjust Dakota people at the time needed to pay a state fee for each visit to the graves of their ancestors there.

Native tribe to get back land 160 years after largest mass hanging in US history | Minnesota | The Guardian

0 notes

Photo

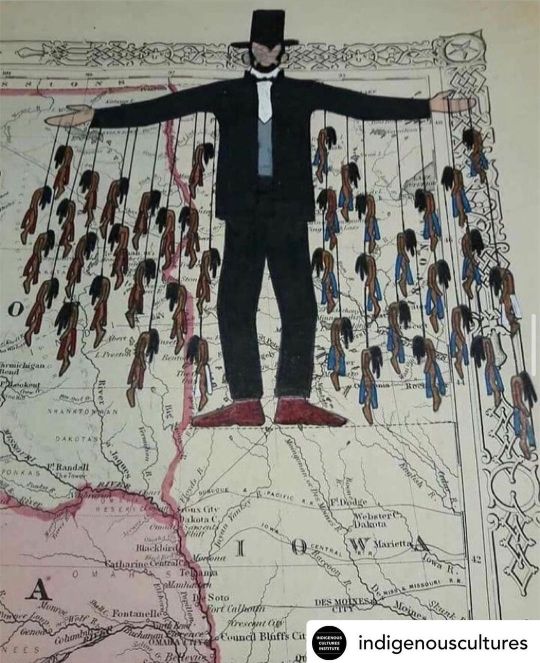

This part of history needs to be known and taught so it will NOT BE REPEATED!! ❤️ 😟 🌀 🌀 😟 ❤️ #waterlandyou #repost #reposting ((All credit to owners.) @indigenouscultures ▫️▪️▫️D A K O T A 3 8 ▫️▪️▫️ ——— December 26, 1862: Under the direction of President Abraham Lincoln, the largest mass execution in US history took place in nearby Mankato, Minnesota. Following colonial encroachment into the Minnesota River Valley [and also Lake Minnetonka], Indigenous people were forcibly relocated to a prison-like setting at Fort Snelling [just south of Minneapolis]. Understandably, this violent expulsion was met with retaliation. In a terror-inducing revenge, the US military rounded up 38 Dakota men — many of whom spiritual leaders, to be hung despite there being any evidence that these men were involved in any “crimes”. This heinous act is remembered by those who ride their horses to the site in honor of the 38 innocent people who were killed. Source: @atsihem #dakota38 #Mankato #Dakota #Minnesota https://www.instagram.com/p/CX90bKgMJkk/?utm_medium=tumblr

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Your Hero is Not Untouchable Pt 2

Your Hero is Not Untouchable

A Monuments Study: Dakota War of 1862 Memorials, Monuments and Markers

by Rye Purvis 7/3/2020

(T.C. Cannon, Kiowa, painting “Andrew Myrick - Let Em Eat Grass” 1970)

On December 26th, 1862 38 Dakota prisoners of war were executed in Mankato, Minnesota. This was to mark an ending (though not an end to the suffering of the Dakota peoples) to the Dakota War of 1862, a war that began just months earlier in the Fall of ’62. The 38 men were ordered to be executed under the order of Abraham Lincoln, after Lincoln’s examined 303 war trials conducted from September to November of ’62 in Minnesota:

“The trials of the Dakota prisoners were deficient in many ways, even by military standards; and the officers who oversaw them did not conduct them according to military law. The hundreds of trials commenced on 28 September 1862 and were completed on 3 November; some lasted less than 5 minutes. No one explained the proceedings to the defendants, nor were the Sioux represented by defense attorneys. "The Dakota were tried, not in a state or federal criminal court, but before a military commission. They were convicted, not for the crime of murder, but for killings committed in warfare. The official review was conducted, not by an appellate court, but by the President of the United States. Many wars took place between Americans and members of the Indian nations, but in no others did the United States apply criminal sanctions to punish those defeated in war." The trials were also conducted in an atmosphere of extreme racist hostility towards the defendants expressed by the citizenry, the elected officials of the state of Minnesota and by the men conducting the trials themselves. "By November 3, the last day of the trials, the Commission had tried 392 Dakota, with as many as 42 tried in a single day." Not surprisingly, given the socially explosive conditions under which the trials took place, by the 10th of November the verdicts were in, and it was announced to the nation and the world that 303 Sioux prisoners had been convicted of murder and rape by the military commission and sentenced to death.” 1

Lincoln reviewed all transcripts from the rushed trials and made his decision on the final execution in under a month. The public execution remains the largest mass execution in American history. Today a public park remains at the site of the execution, named “Reconciliation Park” and given the theme “Forgive Everyone Everything.” 2 Merriam-Webster’s lists its dictionary definition of reconciliation as “the act of causing two people or groups to become friendly again after an argument or disagreement.”

It Starts with Treaties

To provide context to the Dakota War of 1862 is to acknowledge a trail of once again broken treaties and a US hunger for land acquisition. Before colonial interactions, the Great Sioux Nation covered present-day northern Minnesota and Wisconsin. The ancestors of the Sioux “arrived in the Northwoods of central Minnesota and northwestern Wisconsin from the Central Mississippi River shortly before 800 AD.” 3 Under the Great Sioux Nation are three subdivision groups: The Lakota (Northern Lakota, Central Lakota and Southern Lakota), Western Dakota (Yankton, Yanktonai) and the Eastern Dakota (Santee, Sisseton). It wasn’t until the early 1800’s that the Dakota, of the Sioux Nation, signed a treaty with the US in order to establish US Military posts in Minnesota and open trading for the Dakota. Soon after, the 1825 Treaty of Prarie du Chien and the 1830 Fourth Treaty of Prarie du Chien were put into place to cede more land to the American government. Another 1858 Treaty established the Yankton Sioux Reservation for the Yankton Western Dakota peoples, a treaty that ultimately moved the band from “eleven and a half million acres” to a “475,000 acre reservation.”11 The US created the Territory of Minnesota in 1849, thus placing even more pressure on the Sioux to concede land. More treaties followed with the 1851 Treaty of Mendota and the Treaty of Traverse des Sioux. In both deals, 21 million acres were ceded to the US by the Sisseton and Wahpeton bands of the Dakota in exchange for $1,665,000. “However, the American government kept more than 80% of the funds with only the interest (5% for 50 years) being paid to the Dakota” 4

The US’s aim ultimately was to force the Sioux out of Minnesota. Minnesota, established as a state on May 11, 1858 had two temporary reservations set up along the Minnesota River, one for the Upper Sioux Agency and one for the Lower Sioux Agency. Relocation and displacement from land once used for hunting created even more tension with delayed treaty payments causing economic suffering and starvation. Treaties promised payments to the Sioux, payments that were used for foods but at that point but were often late due to the US’s focus on the Civil War. Trader store operators many times charged credit to the Upper and Lower Sioux Agency’s, collecting the annuity allotments directly from the government in return.

Let them eat grass

Having owned stores in both the Upper and Lower Sioux Agency at the time, trader Andrew J Myrick eventually refused to sell food on credit to the Dakota during the summer of 1862. That summer saw additional hardship with failed crops in the previous year on top of late federal payments. In response to his refusal to allot food, Myrick was quoted as “allegedly” saying “Let them eat grass” a quote that is oftentimes disputed. Around the same time as this disputed quote, on August 17, 1862 a few Santee men of the Whapeton band killed a white farmer and part of his family, thus starting the beginning of the Dakota War of 1862.

This is where we in the 21st century have to take a pause. Most of the written accounts of the start of the war or the “murderous violence” of the “Murdering Indians” 5 (a quote from Peter G Beidler’s “Murdering Indians”) were accounts from the side of the colonizers. When researching the Dakota War of 1862, perspectives from the Dakota are not common. At some point the basis for war warrants a question of American mythology. In researching about this white farmer debacle, the killing is in one instance described as coming from “an argument between two young Santee men over the courage to steal eggs from a white farmer became a dare to kill.”6 In another account, the story follows the same narrative about the farmer’s eggs: “Upon seeing some chicken eggs in a nest at the farm of a white settler, there was a disagreement whether or not to take the eggs. When one refused, his companion dared him to prove that he was not afraid of the white man's reaction.”7 I bring up the eggs incident not to stress on this sliver of historical mythology but to emphasize the instability of perspective in historical accounts. Anti-Indian perspectives and a notion of eradication of the “Indian” has been profound in the beginning in the colonization of the US. For a war to rest on the stolen eggs of a farmer, and the killing of 5 individuals doesn’t take into account the broken down persons that were driven to get to the point of having to steal eggs nor what exactly occurred between the farmer and the men.

After the incident, however it occurred, Mdewakanton Dakota leader Little Crow led a group against the American settlements waging war as a means to remove the white settlers. Little Crow as he is known in European mistranslations, name was actually Thaóyate Dúta meaning “His Red Nation”. He was instrumental in leading discussions in the treaties, providing a voice for his people, and leading Dakota in the Battle of Birch Coulee. In a letter to Henry Sibley, the first Governor of the US State of Minnesota, on September 7, 1862, Thaóyate described the context for the uprising:

“Dear Sir – For what reason we have commenced this war I will tell you. it is on account of Maj. Galbrait [sic] we made a treaty with the Government a big for what little we do get and then cant get it till our children was dieing with hunger – it is with the traders that commence Mr A[ndrew] J Myrick told the Indians that they would eat grass or their own dung. Then Mr [William] Forbes told the lower Sioux that [they] were not men [,] then [Louis] Robert he was working with his friends how to defraud us of our money, if the young braves have push the white men I have done this myself." 8

Famine, broken treaties, late payments from the government were but a few of the motivating factors for driving change. The killing of the five white settlers by the 5 Santee men prompted a motion of action led by then natural leader Thaóyate.

When the war neared an end, Thaóyate and other Dakota warriors escaped. It wasn’t until July 3 of 1863 that Thaóyate was shot by 2 settlers and mortally wounded. Upon his death, Thaóyate’s body was mutilated and his remains were withheld from both family and his tribe until 1971 when the Minnesota Historical Society returned his remains to Thaóyate’s grandson. A historical marker remains where Thaóyate’s life was taken:

“[The] marker, erected in 1929 at the spot where Chief Little Crow (who escaped the hanging) was shot, glorifies the chief’s killer: “Chief Little Crow, leader of the Sioux Indian outbreak in 1862, was shot and killed about 330 feet from this point by Nathan Lamson and his son Chauncey July 3, 1863.” The marker does not mention that Little Crow’s body was mutilated, that his scalp was donated to the Minnesota Historical Society and put on display at the State Capitol. He would not be buried until 1971.” 9

Marker of where Little Crow was shot (photo by Sheila Regan)

I just want to acknowledge, that there is a lot of information to unpack that occurred during the Dakota War of 1862, and I don’t want to pretend that this article can sum up every occurrence, battle or person involved. Author and non-Native Gary Clayton Anderson wrote “Through Dakota Eyes” in 1988, and though not perfect, it provides eyewitness accounts from various Dakota peoples perspectives that is worth noting. The Minnesota Historical Society, though known for its problematic history holding on to Thaóyate’s body, also provides more information on its website regarding oral traditions, resources, publications and more in regards to the Dakota War of 1862. I encourage those interested in diving deeper into information to seek out more while simultaneously questioning the source of the information.

Stolen Bodies

Before Thaóyate’s death, the 38 Dakota men were hung at Mankato under Lincoln’s orders. An additional 2 men by the name of Shakpe and Wakanozanzan who had been captured were also executed on November 11th, 1865 under the order of Andrew Johnson. But this mass execution was not the end of the US’s threat to eradicate the Sioux. After the mass execution, “277 male members of the Sioux tribe, 16 women and two children and one member of the Ho-Chunk tribe”1 were sent to a prison camp at Camp McClellan from April 25, 1863 to April 10, 1866. The prisoners who did not survive Camp McClellan were buried in unmarked graves, later dug up and their skulls used by scientists at the Putnam Museum in the late 1870’s. The 23 skulls were given to the Dakota tribe and not until 2005 was a proper memorial ceremony held for the Dakota prisoners.

In addition, 1600 Dakota women, children and old men were forced into internment camps at Pike Island. Wita Tanka, the Dakota name for Pike Island, is now part of Fort Snelling State Park.

“During this time, more than 1600 Dakota women, children and old men were held in an internment camp on Pike Island, near Fort Snelling, Minnesota. Living conditions and sanitation were poor, and infectious disease struck the camp, killing more than three hundred.[37] In April 1863, the U.S. Congress abolished the reservation, declared all previous treaties with the Dakota null and void, and undertook proceedings to expel the Dakota people entirely from Minnesota. To this end, a bounty of $25 per scalp was placed on any Dakota found free within the boundaries of the state.[38] The only exception to this legislation applied to 208 Mdewakanton, who had remained neutral or assisted white settlers in the conflict."1

Where does this leave us?

The year was 1990 and a 36-year old Cheyenne and Arapaho artist by the name of Hock E Aye VI Edgar Heap of Birds had just finished an installation along the Mississippi River in Downtown Minneapolis titled “Building Minnesota.” The installation featured 40 white metal signs containing the names of the 38 men executed under the order of Abraham Lincoln, and the 2 men executed under the order of Andrew Johnson. Heap of Birds explained, “‘Not everyone loved the piece. Heap of Birds says that he received criticism because of the negative portrayal of Abraham Lincoln. ‘They thought it was a betrayal,’”9 Beyond that, the installation came to be known as a space for healing, mourning, for acknowledgement of the lost men, and a place for community to gather.

(One of the 38+2 Signs by Edgar Heap of Birds, photo from Met Museum)

Two monuments were placed up in 1987 and in 2012 at Reconciliation Park in Monkato, MN. The ‘87 monument named “Winter Warrior” features a Dakota warrior figure made by a local artist and the 2012 monument features a large scroll with poems, prayers, and the list of all the men killed on that dark day of 1862.

Beyond that, Minnesota boasts a plethora of statues, monuments and memorials under the umbrella of the Dakota War of 1862. Fort Ridgely State Park located near Fairfax MN hosts a number of monuments, Wood Lake State Monument, Camp Release State Monument, Defenders State Monument are a few of the myriad of locations dedicated to the Americans who fought, lost their lives as well as civilian causality acknowledgement.

Located in Morton, MN, the Birch Coulee monument was erected in 1894. Close to this monument a granite obelisk was erected five years later titled the “Loyal Indian Monument,” to honor the 6 Dakota “who saved the lives of whites during the U.S. Dakota War.” This monument stood out to me, not so much for its bland appearance, but the unusual circumstance to highlight six “loyal” Native lives amongst the many lost who were seen as disloyal.

Seth Eastman, a descendant of Little Thunder (one of the 38 men executed in Mankato) shared how “one public school at the border of Minnesota, where a man dressed as Abraham Lincoln talked to the students and answered their questions [and one] of my nephews asked the question, ‘Why did you hang the 38?’ This man went on to tell him, ‘Oh, I only hung the bad Indians. The ones that killed and raped.’ Telling kids this, that we’re bad, it’s the same as how we’ve been portrayed in the media. That struck my core.””

He continued:

“Minnesota has its own memorials for the Dakota War, but some of the older ones especially are quite problematic. These markers paint the settlers who fought the Dakota as brave victims who defended themselves, without discussion of the broken treaties and ill treatment the Dakota endured which prompted the war; neither is there any mention of the mass execution, internment, and forced removal that followed.”9

Director and Founder of Smooth Feather productions Silas Hagerty released the documentary Dakota 38 in 2012. The documentary highlights a yearly journey where riders from across the world meet in Lower Brule, South Dakota to take a 330-mile journey to Mankato as part of a commemoration and ceremony of remembrance for the 38 lost in 1862. The film also delves into bits of history on the attempts the US took to remove the Dakota peoples from Minnesota. Jim Miller, a direct descendant of Little Horse (one of the 38 men) started the annual ride in 2005 as “a way to promote reconciliation between American Indians and non-Native people. Other goals of the Memorial Ride include: provide healing from historical trauma; remember and honor the 38 + 2 who were hanged; bring awareness of Dakota history and to promote youth rides and healing.”10

(Dakota Riders Ceremonial ride to Mankota, Photo by Sarah Penman)

The memorials and monuments are in abundance in regards to the Dakota War. But who’s perspective is acknowledged? Through work such as Edgar Heap of Birds in his 1990′s installation, to the 2012 larger public scroll monument in Mankato’s “Reconciliation Park” there have been steps taken by both Native and non-natives to explore what this reconciliation looks like.

Of the two Dakota men captured and ordered to be executed under then US president Andrew Johnson on November 11, 1865, Wakanozanzan of the Mdeqakanton Dakota Sioux Nation’s final words were:

“I am a common human being. Some day, the people will come from the heart and look at each other as common human beings. When they do that, come from the heart, this country will be a good place.”12

This article is dedicated to the 38+2.

-------

Images Sources

Andrew Myrick – Let Em Eat Grass 1970 TC Cannon, Google Arts & Culture

https://artsandculture.google.com/asset/andrew-myrick-let-em-eat-grass-t-c-cannon-kiowa-and-caddo-southern-plains-indian-museum/uwGyR0PTzacQkA

Met Museum photo of Edgar Heap of Birds artwork

https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/653721

Mankota riders

https://nativenewsonline.net/currents/dakota-382-wokiksuye-memorial-riders-commemorate-1862-hangings-ordered-lincoln/

Sources

1 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dakota_War_of_1862

2 https://www.mankatolife.com/attractions/reconciliation-park/

3 Gibbon, Guy The Sioux: The Dakota and the Lakota Nations

https://books.google.com/books/about/The_Sioux.html?id=s3gndFhmj9gC

4 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sioux

5 Beidler, Peter G. “Murdering Indians” October 17, 2013

https://books.google.com/books?id=4RRzAQAAQBAJ&dq=santee+men+murdered+white+farmer

6 History of the Santee Sioux Tribe in Nebraska

http://www.santeedakota.org/santee_history_ii.htm

7 https://www.usdakotawar.org/history/acton-incident

8 Little Crow’s Letter

https://www.usdakotawar.org/history/taoyateduta-little-crow

9 Regan, Sheila June 16, 2017 “In Minnesota, Listening to Native Perspective on Memorializing the Dakota War” Hyperallergic

https://hyperallergic.com/385682/in-minnesota-listening-to-native-perspectives-on-memorializing-the-dakota-war/

10 https://nativenewsonline.net/currents/dakota-382-wokiksuye-memorial-riders-commemorate-1862-hangings-ordered-lincoln/

11 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Yankton_Sioux_Tribe

12 https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/64427183/wakan_ozanzan-medicine_bottle

Monuments Depicting Victims of the Dakota Uprising

http://www.dakotavictims1862.com/monuments/index.html

Morton, MN Monuments

https://sites.google.com/site/mnvhlc/home/renville-county/morton-monuments

More information regarding Dakota War of 1862

Holocaust and Genocide Studies: Native American University of Minnesota

https://cla.umn.edu/chgs/holocaust-genocide-education/resource-guides/native-american

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

38, by Layli Long Soldier

Here, the sentence will be respected.

I will compose each sentence with care by minding what the rules of writing dictate.

For example, all sentences will begin with capital letters.

Likewise, the history of the sentence will be honored by ending each one with appropriate punctuation such as a period or question mark, thus bringing the idea to (momentary) completion.

You may like to know, I do not consider this a “creative piece.”

In other words, I do not regard this as a poem of great imagination or a work of fiction.

Also, historical events will not be dramatized for an interesting read.

Therefore, I feel most responsible to the orderly sentence; conveyor of thought.

That said, I will begin:

You may or may not have heard about the Dakota 38.

If this is the first time you’ve heard of it, you might wonder, “What is the Dakota 38?”

The Dakota 38 refers to thirty-eight Dakota men who were executed by hanging, under orders from President Abraham Lincoln.

To date, this is the largest “legal” mass execution in U.S. history.

The hanging took place on December 26th, 1862—the day after Christmas.

This was the same week that President Lincoln signed The Emancipation Proclamation.

In the preceding sentence, I italicize “same week” for emphasis.

There was a movie titled Lincoln about the presidency of Abraham Lincoln.

The signing of The Emancipation Proclamation was included in the film Lincoln; the hanging of the Dakota 38 was not.

In any case, you might be asking, “Why were thirty-eight Dakota men hung?”

As a side note, the past tense of hang is hung, but when referring to the capital punishment of hanging, the correct tense is hanged.

So it’s possible that you’re asking, “Why were thirty-eight Dakota men hanged?”

They were hanged for The Sioux Uprising.

I want to tell you about The Sioux Uprising, but I don’t know where to begin.

I may jump around and details will not unfold in chronological order.

Keep in mind, I am not a historian.

So I will recount facts as best as I can, given limited resources and understanding.

Before Minnesota was a state, the Minnesota region, generally speaking, was the traditional homeland for Dakota, Anishnaabeg and Ho-Chunk people.

During the 1800s, when the U.S. expanded territory, they “purchased” land from the Dakota people as well as the other tribes.

But another way to understand that sort of “purchase” is: Dakota leaders ceded land to the U.S. Government in exchange for money and goods, but most importantly, the safety of their people.

Some say that Dakota leaders did not understand the terms they were entering, or they never would have agreed.

Even others call the entire negotiation, “trickery.”

But to make whatever-it-was official and binding, the U. S. Government drew up an initial treaty.

This treaty was later replaced by another (more convenient) treaty, and then another.

I’ve had difficulty unraveling the terms of these treaties, given the legal speak and congressional language.

As treaties were abrogated (broken) and new treaties were drafted, one after another, the new treaties often referenced old defunct treaties and it is a muddy, switchback trail to follow.

Although I often feel lost on this trail, I know I am not alone.

However, as best as I can put the facts together, in 1851, Dakota territory was contained to a 12-mile by 150-mile long strip along the Minnesota river.

But just seven years later, in 1858, the northern portion was ceded (taken) and the southern portion was (conveniently) allotted, which reduced Dakota land to a stark 10-mile tract.

These amended and broken treaties are often referred to as The Minnesota Treaties.

The word Minnesota comes from mni which means water; sota which means turbid.

Synonyms for turbid include muddy, unclear, cloudy, confused and smoky.

Everything is in the language we use.

For example, a treaty is, essentially, a contract between two sovereign nations.

The U.S. treaties with the Dakota Nation were legal contracts that promised money.

It could be said, this money was payment for the land the Dakota ceded; for living within assigned boundaries (a reservation); and for relinquishing rights to their vast hunting territory which, in turn, made Dakota people dependent on other means to survive: money.

The previous sentence is circular, which is akin to so many aspects of history.

As you may have guessed by now, the money promised in the turbid treaties did not make it into the hands of Dakota people.

In addition, local government traders would not offer credit to “Indians” to purchase food or goods.

Without money, store credit or rights to hunt beyond their 10-mile tract of land, Dakota people began to starve.

The Dakota people were starving.

The Dakota people starved.

In the preceding sentence, the word “starved” does not need italics for emphasis.

One should read, “The Dakota people starved,” as a straightforward and plainly stated fact.

As a result—and without other options but to continue to starve—Dakota people retaliated.

Dakota warriors organized, struck out and killed settlers and traders.

This revolt is called The Sioux Uprising.

Eventually, the U.S. Cavalry came to Mnisota to confront the Uprising.

Over one thousand Dakota people were sent to prison.

As already mentioned, thirty-eight Dakota men were subsequently hanged.

After the hanging, those one thousand Dakota prisoners were released.

However, as further consequence, what remained of Dakota territory in Mnisota was dissolved (stolen).

The Dakota people had no land to return to.

This means they were exiled.

Homeless, the Dakota people of Mnisota were relocated (forced) onto reservations in South Dakota and Nebraska.

Now, every year, a group called the The Dakota 38 + 2 Riders conduct a memorial horse ride from Lower Brule, South Dakota to Mankato, Mnisota.

The Memorial Riders travel 325 miles on horseback for eighteen days, sometimes through sub-zero blizzards.

They conclude their journey on December 26th, the day of the hanging.

Memorials help focus our memory on particular people or events.

Often, memorials come in the forms of plaques, statues or gravestones.

The memorial for the Dakota 38 is not an object inscribed with words, but an act.

Yet, I started this piece (which I do not consider a poem or work of fiction) because I was interested in writing about grasses.

So, there is one other event to include, although it’s not in chronological order and we must backtrack a little.

When the Dakota people were starving, as you may remember, government traders would not extend store credit to “Indians.”

One trader named Andrew Myrick is famous for his refusal to provide credit to Dakotas by saying, “If they are hungry, let them eat grass.”

There are variations of Myrick’s words, but they are all something to that effect.

When settlers and traders were killed during the Sioux Uprising, one of the first to be executed by the Dakota was Andrew Myrick.

When Myrick’s body was found,

his mouth was stuffed with grass.

I am inclined to call this act by the Dakota warriors a poem.

There’s irony in their poem.

There was no text.

“Real” poems do not “really” require words.

I have italicized the previous sentence to indicate inner dialogue; a revealing moment.

But, on second thought, the particular words “Let them eat grass,” click the gears of the poem into place.

So, we could also say, language and word choice are crucial to the poem’s work.

Things are circling back again.

Sometimes, when in a circle, if I wish to exit, I must leap.

And let the body swing.

From the platform.

Out

to the grasses.

15 notes

·

View notes

Photo

38 Dakota Sioux Largest Mass Execution in US

Annuities and provisions promised to Indians through government treaties were slow in being delivered, leaving Dakota Sioux people, who were restricted to reservation lands on the Minnesota frontier, starving and desperate. After a raid of nearby white farms for food turned into a deadly encounter, Dakotas continued raiding, leading to the Little Crow War of 1862, in which 490 settlers, mostly women and children, were killed. President Lincoln sent soldiers, who defeated the Dakota; and after a series of mass trials, more than 300 Dakota men were sentenced to death.

While Lincoln commuted most of the sentences, on the day after Christmas at Mankato, military officials hung 38 Dakotas at once—the largest mass execution in American history. More than 4,000 people gathered in the streets to watch, many bringing picnic baskets. The 38 were buried in a shallow grave along the Minnesota River, but physicians dug up most of the bodies to use as medical cadavers

178 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Evidence of Friday, June 15, 2018

In the description of this blog, I state that I find that God defends me from this evil organization that has come to rule the land, the courts and officers that have abandoned the worthy traditions upon which our country was founded and now act with abandon to undermine our civil liberties, divide our country into factions, favor the religion of psychiatry, women over men, the rich over poor, those accused of crime over those accused of mental illness, and, in my case, the government has stolen twelve years of my service by the use of a trick: falsely promising me this reward: money sufficient to pursue a career as a singer or an actor.

And what have been the consequences upon me and my house that were engendered by their abandonment of the common sense guide that a man must be able to confront his accusers in court?

Here follows the tale of how I met my first, and most damaging, accuser.

When I was a young man just starting to make my way in the world, I chanced to meet a woman at a Halloween Dance in Minneapolis, Debbra Myers. She was about five years older than me and not of the type that I would normally desire as a sexual partner, but I was loathe to make the long drive home after the party and She invited me to stay the night with her following the celebration; we slept together.

The following day, I awoke in her bed to find that we were greeted by her three young sons. After breakfast with her sons and her female partner in renting the house, a co-worker from the restaurant where she worked, I jumped in my white Nissan automobile and drove back to my mother’s house in Mankato.

Being young and not established in a career or with sufficient money to afford to rent a room when I traveled or to buy a home of my own, I would stay with Debbra in Minneapolis when I had the occasion to travel there.

After a time, she took the occasion to visit me at my mother’s house in Mankato. In this way she learned that what I had been telling her about myself was true. I was the only son of a doctor and surgeon, had graduated from Harvard, and that my father had left my mother, moving out of his big, fine house, leaving it to her.

She was allowed to stay with me in my bed that night, only this time, her birth control failed and she became pregnant.

She was distraught. How could this have happened? How could she support another child by herself? Abortion seemed to be the right choice for her.

I, too, was distraught. Debbra was my first sexual partner in a long time and the first since I had been tricked by Wendy Gross, a male to female transsexual I had met in New York City. (I had expended my grandfather’s bequest to me to travel there and across the country, learning about the entertainment trade.

It was there, (and when I was on my last dime and most susceptible to an offer of employment,) that Stanley H. Holler III of the British American Petroleum Company made me an offer. I turned it down.

Wendy was his companion. She turned to me when Stanley threw her out of his room at the Hotel Chelsea, she said, and asked to stay with me for the night in room 100.

You can’t imagine the relief I felt when Debbra first took me as her lover.

(The coincidence of the pairing of issues of gender identity with work roles in ’81 revived in me the issues I had discussed with David Swanson on March 3, 1965, and gave rise to my firm belief that “Wendy” was the transsexual reinvention of David, who must have acted on my putative offer of marriage in ’65 and been brought in with Stanley to reinforce the pressure on me to accept his offer.)

Nor could I agree to have my first conceived child aborted.

As Debbra was now seriously interested in me as a husband, partner and support; and I was interested in her as the future mother of my child, partner and support; we moved in together.

It became summer and she left her job on the West Bank area of the city, (also known as Cedar-Riverside,) to take a summer job as a cook for Outward Bound school and camp in Ely, MN. I traveled with her there and we shared a cabin on their grounds for a while. It was in this cabin that the disagreement between us first became physical.

She had long been contemplating driving to Duluth for an abortion, but as she had no car, she needed my cooperation to do it. I wouldn’t lend my cooperation to the arrangement and denied her the use of my car. As she was leaving the cabin after discussing this with me, I saw her grab the keys from the table. I followed her through the door and tackled her, retrieving my keys. I was careful not to let her be injured, as she was carrying my baby, but she was incensed that I would lay hands on her.

She insisted that I get counseling. I maintained that I had acted properly and within my rights, refusing counseling. Nonetheless, management would not countenance a feuding couple on their grounds and we were asked to cohabitate elsewhere.

We moved into a tiny house in town. It was right across from the courthouse. Debbra commuted the short distance to the Outward Bound camp and looked to me to find some kind of work in town to supplement her income.

As for myself, I continued my series of messages to the President of the United States, looking to capitalize on the growing evidence that the Almighty supported me in my contention that the government had stolen twelve years of my service using means both forceful, (under the terms of Minnesota’s Compulsory School Attendance Act, and allowed by the federal government in violation of the 14th Amendment guaranteeing Due Process of Law before an individual’s rights are reduced,) and fraudulent, (under the terms of the instruction that I had received early in my education and presumed to continue throughout the school system, thereafter.)

Debbra had supported me in this endeavor when we lived together in Minneapolis: She had driven with me to Victoria, MN to mail one of my letters from there. I felt that a postage cancelation mark with the Victoria name would symbolically invoke the memory of the recent Victor/Victoria movie, a tale of gender identity woes reminiscent of the issues in my story and related in earlier letters in my series.

I used this tactic to help any one who may have been assigned to open and read my letters recall the foundation of the series without burdening myself or the reader with a re-telling of the entire tale.

It was at this juncture that I sereptitiously took a $20 from Debbra’s wallet to pay for the extra postage required for Registered Mail. I felt that this was justified for two reasons: 1. the information in my letter related to the security of the nation as well as that of the President, himself, justifying the use of the most secure method for sending a letter, and 2. when the Evidence became so great as to become irrefutable, the government would condescend to pay for the lengthy term of service I maintained it had solicited of me through the men and women it had placed over me, and Debbra, who’s interests were now intertwined with mine, would also benefit.

When she discovered the missing bill, however, she was dismissive of my rationale for taking it and very angry.

Not long after that blow-up, however, our entire family stopped at the DQ in Shakopee, for a treat. A light wind was blowing and in it, a twenty dollar bill.

Debbra saw it without anyone else seeing it first and grabbed it. She insisted that it was entirely her luck that had brought her the twenty. I felt that I had used her twenty for God’s business as well as hers and mine, and that He had returned it to her, satisfying the grievance.

She maintained that I still owed her money and required that I make good on the debt.

What a pity that we didn’t see eye to eye on this mystery. It was a difference between us that would shape the rest of our time together and lead to our eventual parting of ways.

As for the Evidence of Friday, June 15th, 2018?

The preferential prosecution of men over women in cases of domestic abuse, the ability of a reporter to lambast a victim without being held to account in probate court, the preference of the courts to award custody of younger children to the mother and also to the stronger provider, combined with the resistance of the government to award me my just due after dozens of years of service to the government, all these have combined to deprive me of the affections of my daughter, felt most acutely this Father’s Day.

On this past Friday, leading into Father’s Day weekend, I spent the day texting my daughter, Cassie. Inviting her to attend a concert at the Dakota Jazz Club that evening. Telling her about how the owner had offered to give the two of us complimentary admission to any performance there, when I told him of how much sorrow I endured because of Cassie’s rejection. Inviting her to call the club to ask the owner if he, indeed, had made that promise. Calling the club to remind the owner of his promise. Calling his sister to help me contact the owner when I couldn’t reach him at the club. Reviewing my available cash to offer the owner as a bribe to let us in if the date was sold out and he didn’t remember his promise. And generally pulling my last hair out in order to bring Cassie and myself together again, which I desire with all my heart.

This is the loss which the enemies of American liberty and justice endured on that day: As reported on page A6 on the Sunday, June 17th edition of the Star Tribune, “Inmate fatally shoots 2 deputies” (Kansas) and on page B3 of the same edition, “Blaine officer, wife killed in motorcycle crash.”

While you may argue that these losses are not extraordinary to the daily occurrence among law enforcement, please allow me to consider them the work of a Divine force of protection afflicting evil-doers.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Maiden Rock - A Novel of the Winona Myth

As it has been so long since I've kept an active blog of what I'm currently writing about, I decided to schedule some blog posts regarding my current projects, which include an undertaking that rests very close to home.

Since I began writing, I've always wanted to write about where I come from, but, unfortunately, for the most part, where I come from is pretty . . . well, boring. It's nothing like the famous, ancient cities where most of my novels take place, full of old wars and kingdoms long past.

Or at least, that's what I grew up thinking.

I grew up in southeastern Minnesota, where nothing too impressive ever seems to happen. There's lots of farmers and doctors (looking at you, Mayo Clinic), but not a whole lot of action or adventure. Not in the history that we talk about, anyway.

But I've begun to realize that it isn't because it isn't there. It's just because we don't like to talk about it. We don't like to broach subjects that might uncomfortable. So, instead, we all but erased the very real history of this land, which is rich and thrilling. At least, in my opinion as a writer of primarily fantasy based writing, it's much more interesting than the history of farming.

Southeastern Minnesota has a strong Dakota Sioux history, which can be seen in the very name the state was given. (Hint: It comes from Mnisota in the Dakota language, meaning "cloudy water" -- according to the internet that is; I'm no expert). In fact, it's almost impossible to go anywhere around here that doesn't have the Dakotas to thank for its name. And yet, I know almost nothing about this history that happened in my own back yard.

Even though I grew up speaking words from the Dakota language and going to places with great significance to their culture, I never knew very much about any of it. Of course, we all know why that is.

I see Minnesota as a place that can't quite decide what it wants to do about its heritage. On the one hand, we have a history of atrocities enacted against the Dakota people (I'm looking at you Mankato Massacre), while on the other hand several hundred places around the state have kept their Dakota names in place and places like Winona (best known as the Winona Ryder's namesake) and Wabasha erect statues honoring the very people they once drove out.

(Photos Courteousy of the Diversity Foundation and Winona Daily News)

Which is what lead me to my story idea.

See that woman up there in the bottom photo? That's Winona. Or "Princess Winona" as she's commonly known to the white folk in the area. See I grew up hearing a version of her story told by my grandpa, and my uncles, and my mother, and my father, and pretty much anyone else with pale skin and European blood. And their version of the story went something like this:

"Once upon a time, there was a little Indian princess named Nona who was forcibly married to a man she did not love. And, instead of going through with the marriage, she threw herself off of Sugarloaf bluff. And when her husband saw what she had done, he cried, 'Why, Nona?' And ever since that day, this place has been called Winona in her honor."

Yeah, it's pretty . . . awful in that form. For many reasons. So many reasons. Not least of which is that that version teaches you to say the town name incorrectly.

But it got me thinking. All stories come from somewhere, right? And I could guess that there really was some sort of Winona myth -- I mean, there really was a town called Winona and it really did have a statue of a Dakota woman whose name was supposedly Winona. So there had to be a story in there somewhere, right? Right.

And so began my research. I had the whole of the internet at my disposal. I was bound to find and endless stream of information on this subject, right?

Not so right.

See, while Winona's arts and culture society might be doing their darnedest to make right the wrongs of the past today, they can't undo generations of steamrolling overtop of the Dakota culture. There are certain things that we will just never get back, histories of this area that are lost forever. And so, what you're able to find on the internet of Dakota legends and histories, is . . . scattered at best.

What I did find out is this: The story of a Native American woman throwing herself off of a cliff to avoid an unwanted marriage is a common one, that shows up in almost every tribe's legends. And there really is a Dakota legend of that very kind that is said to take place near Winona, MN. Only, by near, I mean over 40 miles away and on the other side of the river in Pepin, WI. And her name wasn't Winona, because Winona wasn't a name. It was a title given to the first born daughter of any family.

From what I can tell, it seems that the title Winona being associated with this myth is a case of historians getting it wrong. See in the 1800's a man who came to the area wrote down a bunch of stories told to him by the people of Chief Wapasha's tribe. (You might remember him as the other statue pictured above.) And somehow, he ended up thinking that the woman in the story was a member of Wapasha's ancestral family -- the first born daughter of a previous Chief Wapasha that would have been commonly known as Winona.

That's what I've taken away from what I've been able to find anyway.

And there are many different versions of the story floating around out there. In most versions of the story, she is indeed the daughter of the chief and she is promised in marriage to a warrior in a nearby tribe. Distraught, the woman decides on the night of her wedding, that she can't bear to live the life that's being forced upon her, and so in a fit of desperation, she throws herself from the top of a bluff rather than continue. In another version, it isn't a man from a nearby tribe that she's being forced to marry but a French fur trader. And in yet others, she may not have been the chief's daughter at all.

Regardless of which of these versions could be considered the "correct" one, I felt like this "Winona" figure had really been short changed. I felt like there was more to tell with her story, that wasn't covered in the myth, and so I decided to explore it more myself.

Moreso, I'm sick of seeing cliche of "woman kills herself over a man" and so decided that the Winona I was writing, my Winona, wouldn't have taken her own life unless she had more of a reason to do so.

At the same time, I've always looked up at the bluffs surrounding Winona and thought that many of them looked like the craggy faces of old men, slumbering under layers of grass and trees, just waiting to be woken once again. (Think the guardians in Disney's Atlantis.)

These two stories combined, I came up with what has become my novel Maiden Rock, and the story of two young woman, separated by time and culture but connected through one overarching purpose.

#writing#novel#too many novels#writer problems#winona myth#dakota#sioux#minnesota based story#minnesota

1 note

·

View note

Photo

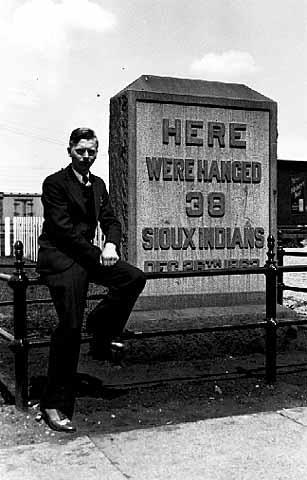

On the day after Christmas, 1912, several hundred people gathered at the corner of what was then Front and Main streets in downtown Mankato, Minnesota, to mark the 50th anniversary of the largest mass hanging in U.S. history. Thirty-eight Dakota men had been executed at that exact spot for crimes allegedly committed during the U.S.-Dakota War of 1862. The highlight of the 50th anniversary commemoration was the dedication of a granite monument inscribed with the words, “Here Were Hanged 38 Sioux Indians.”

In his dedication address, Judge Lorin Cray rejected any notion that the monument inappropriately glorified a mass killing. As the Mankato Free Press reported, he “wished to have it understood that the monument [had] not been erected to gloat over the deaths of the redmen,” but was instead meant “simply to record accurately an event in history.”

The following year, in 1863, more than 6000 Dakota people were forced to leave their home land and relocate to South Dakota and Nebraska.The name “Minnesota” itself, is a Dakota word that means, “Sky Tinted Water”.

The judge’s assessment held sway for more than four decades.

183 notes

·

View notes

Photo

On this week more than 150 years ago, dozens of Native American men were killed by the government in the largest mass execution in US history. In the Dakota War of 1862, also known as the Sioux Uprising, groups of Dakota (part of the Sioux group of Native American tribes) were angry with the US government over broken land treaties and late annuity payments. Times were tough, too, and Dakota families were starving. Dakota natives went to war against white settlers in Minnesota, which had just become a state four years prior. The fighting lasted six weeks, according to the Minnesota History Center. More than 500 white people and 60 natives died in the fighting, the Wisconsin Historical Society reports. The uprising ended on December 26, when 38 Dakota natives were hanged in Mankato, Minnesota, in a mass execution. The remaining natives were forced to leave Minnesota -- at first being held at a camp and then being sent out of the state. Originally, more than 300 men were sentenced to hanging by then Minnesota Gov. Alexander Ramsey. The number was reduced when President Abraham Lincoln wrote a letter to the governor, listing 39 names to be hanged instead. One was later granted a reprieve. CNN 20191229 (at Mankato, Minnesota) https://www.instagram.com/p/B6qZSVLHm18/?igshid=pysnzj3ovi8j

0 notes

Text

“38,” Layli Long Soldier

Here, the sentence will be respected.

I will compose each sentence with care, by minding what the rules of writing dictate.

For example, all sentences will begin with capital letters.

Likewise, the history of the sentence will be honored by ending each one with appropriate

punctuation such as a period or question mark, thus bringing the idea to (momentary) completion.

You may like to know, I do not consider this a “creative piece.”

I do not regard this as a poem of great imagination or a work of fiction.

Also, historical events will not be dramatized for an “interesting” read.

Therefore, I feel most responsible to the orderly sentence; conveyor of thought.

That said, I will begin.

You may or may not have heard about the Dakota 38.

If this is the first time you’ve heard of it, you might wonder, “What is the Dakota 38?”

The Dakota 38 refers to thirty-eight Dakota men who were executed by hanging, under

orders from President Abraham Lincoln.

To date, this is the largest “legal” mass execution in US history.

The hanging took place on December 26, 1862—the day after Christmas.

This was the same week that President Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation.

In the preceding sentence, I italicize “same week” for emphasis.

There was a movie titled Lincoln about the presidency of Abraham Lincoln.

The signing of the Emancipation Proclamation was included in the film Lincoln; the

hanging of the Dakota 38 was not.

In any case, you might be asking, “Why were thirty-eight Dakota men hung?”

As a side note, the past tense of hang is hung, but when referring to the capital punishment

of hanging, the correct past tense is hanged.

So it’s possible that you’re asking, “Why were thirty-eight Dakota men hanged?”

They were hanged for the Sioux Uprising.

I want to tell you about the Sioux Uprising, but I don’t know where to begin.

I may jump around and details will not unfold in chronological order.

Keep in mind, I am not a historian.

So I will recount facts as best as I can, given limited resources and understanding.

Before Minnesota was a state, the Minnesota region, generally speaking, was the

traditional homeland for Dakota, Anishinaabeg, and Ho-Chunk people.

During the 1800s, when the US expanded territory, they “purchased” land from the Dakota

people as well as the other tribes.

But another way to understand that sort of “purchase” is: Dakota leaders ceded land to the

US government in exchange for money or goods, but most importantly, the safety of their people.

Some say that Dakota leaders did not understand the terms they were entering, or they

never would have agreed.

Even others call the entire negotiation “trickery.”

But to make whatever-it-was official and binding, the US government drew up an initial treaty.

This treaty was later replaced by another (more convenient) treaty, and then another.

I’ve had difficulty unraveling the terms of these treaties, given the legal speak and

congressional language.

As treaties were abrogated (broken) and new treaties were drafted, one after another, the

new treaties often referenced old defunct treaties, and it is a muddy, switchback trail to follow.

Although I often feel lost on this trail, I know I am not alone.

However, as best as I can put the facts together, in 1851, Dakota territory was contained to a

twelve-mile by one-hundred-fifty-mile long strip along the Minnesota River.

But just seven years later, in 1858, the northern portion was ceded (taken) and the

southern portion was (conveniently) allotted, which reduced Dakota land to a stark ten-mile tract.

These amended and broken treaties are often referred to as the Minnesota Treaties.

The word Minnesota comes from mni, which means water; and sota, which means turbid.

Synonyms for turbid include muddy, unclear, cloudy, confused, and smoky.

Everything is in the language we use.

For example, a treaty is, essentially, a contract between two sovereign nations.

The US treaties with the Dakota Nation were legal contracts that promised money.

It could be said, this money was payment for the land the Dakota ceded; for living within

assigned boundaries (a reservation); and for relinquishing rights to their vast hunting

territory which, in turn, made Dakota people dependent on other means to survive: money.

The previous sentence is circular, akin to so many aspects of history.

As you may have guessed by now, the money promised in the turbid treaties did not make it

into the hands of Dakota people.

In addition, local government traders would not offer credit to “Indians” to purchase food

or goods.

Without money, store credit, or rights to hunt beyond their ten-mile tract of land, Dakota

people began to starve.

The Dakota people were starving.

The Dakota people starved.

In the preceding sentence, the word “starved” does not need italics for emphasis.

One should read “The Dakota people starved” as a straightforward and plainly stated fact.

As a result—and without other options but to continue to starve—Dakota people retaliated.

Dakota warriors organized, struck out, and killed settlers and traders.

This revolt is called the Sioux Uprising.

Eventually, the US Cavalry came to Mnisota to confront the Uprising.

More than one thousand Dakota people were sent to prison.

As already mentioned, thirty-eight Dakota men were subsequently hanged.

After the hanging, those one thousand Dakota prisoners were released.

However, as further consequence, what remained of Dakota territory in Mnisota was

dissolved (stolen).

The Dakota people had no land to return to.

This means they were exiled.

Homeless, the Dakota people of Mnisota were relocated (forced) onto reservations in

South Dakota and Nebraska.

Now, every year, a group called the Dakota 38 + 2 Riders conduct a memorial horse ride

from Lower Brule, South Dakota, to Mankato, Mnisota.

The Memorial Riders travel 325 miles on horseback for eighteen days, sometimes through

sub-zero blizzards.

They conclude their journey on December 26, the day of the hanging.

Memorials help focus our memory on particular people or events.

Often, memorials come in the forms of plaques, statues, or gravestones.

The memorial for the Dakota 38 is not an object inscribed with words, but an act.

Yet, I started this piece because I was interested in writing about grasses.

So, there is one other event to include, although it’s not in chronological order and we must

backtrack a little.

When the Dakota people were starving, as you may remember, government traders would

not extend store credit to “Indians.”

One trader named Andrew Myrick is famous for his refusal to provide credit to Dakota

people by saying, “If they are hungry, let them eat grass.”

There are variations of Myrick’s words, but they are all something to that effect.

When settlers and traders were killed during the Sioux Uprising, one of the first to be

executed by the Dakota was Andrew Myrick.

When Myrick’s body was found,

his mouth was stuffed with grass.

I am inclined to call this act by the Dakota warriors a poem.

There’s irony in their poem.

There was no text.

“Real” poems do not “really” require words.

I have italicized the previous sentence to indicate inner dialogue, a revealing moment.

But, on second thought, the words “Let them eat grass” click the gears of the poem into place.

So, we could also say, language and word choice are crucial to the poem’s work.

Things are circling back again.

Sometimes, when in a circle, if I wish to exit, I must leap.

And let the body swing.

From the platform.

Out

to the grasses.

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Largest Mass Execution in US History (1862)

The Dakota War of 1862, also known as the Sioux Uprising, (and the Dakota Uprising, the Sioux Outbreak of 1862, the Dakota Conflict, the U.S.–Dakota War of 1862 or Little Crow's War) was an armed conflict between the United States and several bands of the eastern Sioux (also known as eastern Dakota). It began on August 17, 1862, along the Minnesota River in southwest Minnesota. It ended with a mass execution of 38 Dakota men on December 26, 1862, in Mankato, Minnesota.

Throughout the late 1850s, treaty violations by the United States and late or unfair annuity payments by Indian agents caused increasing hunger and hardship among the Dakota. Traders with the Dakota previously had demanded that the government give the annuity payments directly to them (introducing the possibility of unfair dealing between the agents and the traders to the exclusion of the Dakota). In mid-1862 the Dakota demanded the annuities directly from their agent, Thomas J. Galbraith. The traders refused to provide any more supplies on credit under those conditions, and negotiations reached an impasse.[3]

On August 17, 1862, one young Dakota with a hunting party of three others killed five settlers while on a hunting expedition. That night a council of Dakota decided to attack settlements throughout the Minnesota River valley to try to drive whites out of the area. There has never been an official report on the number of settlers killed, although figures as high as 800 have been cited.

Over the next several months, continued battles pitting the Dakota against settlers and later, the United States Army, ended with the surrender of most of the Dakota bands.[4] By late December 1862, soldiers had taken captive more than a thousand Dakota, who were interned in jails in Minnesota. After trials and sentencing, 38 Dakota were hanged on December 26, 1862, in the largest one-day execution in American history. In April 1863, the rest of the Dakota were expelled from Minnesota to Nebraska and South Dakota. The United States Congress abolished their reservations.

Background

Previous treaties

The United States and Dakota leaders negotiated the Treaty of Traverse des Sioux[5] on July 23, 1851, and Treaty of Mendota on August 5, 1851, by which the Dakota were forced to cede large tracts of land in Minnesota Territory to the U.S. In exchange for money and goods, the Dakota were forced to agree to live on a 20-mile (32 km) wide Indian reservation centered on a 150 mile (240 km) stretch of the upper Minnesota River.

However, the United States Senate deleted Article 3 of each treaty, which set out reservations, during the ratification process. Much of the promised compensation never arrived, was lost, or was effectively stolen due to corruption in the Bureau of Indian Affairs. Also, annuity payments guaranteed to the Dakota often were provided directly to traders instead (to pay off debts which the Dakota incurred with the traders).

Encroachments on Dakota lands

Little Crow, Dakota chief

When Minnesota became a state on May 11, 1858, representatives of several Dakota bands led by Little Crow traveled to Washington, D.C., to negotiate about enforcing existing treaties. The northern half of the reservation along the Minnesota River was lost, and rights to the quarry at Pipestone, Minnesota, were also taken from the Dakota. This was a major blow to the standing of Little Crow in the Dakota community.

The land was divided into townships and plots for settlement. Logging and agriculture on these plots eliminated surrounding forests and prairies, which interrupted the Dakota's annual cycle of farming, hunting, fishing and gathering wild rice. Hunting by settlers dramatically reduced wild game, such as bison, elk, whitetail deer and bear. Not only did this decrease the meat available for the Dakota in southern and western Minnesota, but it directly reduced their ability to sell furs to traders for additional supplies.

Although payments were guaranteed, the US government was often behind or failed to pay because of Federal preoccupation with the American Civil War. Most land in the river valley was not arable, and hunting could no longer support the Dakota community. The Dakota became increasingly discontented over their losses: land, non-payment of annuities, past broken treaties, plus food shortages and famine following crop failure. Tensions increased through the summer of 1862.

Breakdown of negotiations

On August 4, 1862, representatives of the northern Sissetowan and Wahpeton Dakota bands met at the Upper Sioux Agency in the northwestern part of the reservation and successfully negotiated to obtain food. When two other bands of the Dakota, the southern Mdewakanton and the Wahpekute, turned to the Lower Sioux Agency for supplies on August 15, 1862, they were rejected. Indian Agent (and Minnesota State Senator) Thomas Galbraith managed the area and would not distribute food to these bands without payment.

At a meeting of the Dakota, the U.S. government and local traders, the Dakota representatives asked the representative of the government traders, Andrew Jackson Myrick, to sell them food on credit. His response was said to be, "So far as I am concerned, if they are hungry let them eat grass or their own dung." [6] But the importance of Myrick's comment at the time, early August 1862, is historically unclear. When Gregory Michno shared the top 10 myths on the Dakota Uprising in True West Magazine, he stated that this statement did not incite the uprising: "An interpreter’s daughter first mentioned it 57 years after the event. Since then, however, the claim that this incited the Dakotas to revolt has proliferated as truth in virtually every subsequent retelling. Like so much of our history, unfortunately, repetition is equated with accuracy." [7] Another telling is that Myrick's was referring the Native American women who were already combing the floor of the fort's stables for any unprocessed oats to then feed to their starving children along with a little grass. Myrick was later found dead with grass stuffed in his mouth.[8]

War

Early fighting

On August 16, 1862, the treaty payments to the Dakota arrived in St. Paul, Minnesota, and were brought to Fort Ridgely the next day. They arrived too late to prevent violence. On August 17, 1862, four young Dakota men were on a hunting trip in Acton Township, Minnesota, during which one stole eggs and then killed five white settlers.[9] Soon after, a Dakota war council was convened and their leader, Little Crow, agreed to continue attacks on the European-American settlements to try to drive out the whites.

On August 18, 1862, Little Crow led a group that attacked the Lower Sioux (or Redwood) Agency. Andrew Myrick was among the first who were killed.[citation needed] He was discovered trying to escape through a second-floor window of a building at the agency. Myrick's body later was found with grass stuffed into his mouth. The warriors burned the buildings at the Lower Sioux Agency, giving enough time for settlers to escape across the river at Redwood Ferry. Minnesota militia forces and B Company of the 5th Minnesota Volunteer Infantry Regiment sent to quell the uprising were defeated at the Battle of Redwood Ferry. Twenty-four soldiers, including the party's commander (Captain John Marsh), were killed in the battle.[citation needed] Throughout the day, Dakota war parties swept the Minnesota River Valley and near vicinity, killing many settlers. Numerous settlements including the Townships of Milford, Leavenworth and Sacred Heart, were surrounded and burned and their populations nearly exterminated.

Early Dakota offensives

1912 lithograph depicting the 1862 Battle of Birch Coulee, by Paul G. Biersach (1845-1927)

Confident with their initial success, the Dakota continued their offensive and attacked the settlement of New Ulm, Minnesota, on August 19, 1862, and again on August 23, 1862. Dakota warriors initially decided not to attack the heavily defended Fort Ridgely along the river. They turned toward the town, killing settlers along the way. By the time New Ulm was attacked, residents had organized defenses in the town center and were able to keep the Dakota at bay during the brief siege. Dakota warriors penetrated parts of the defenses enough to burn much of the town.[10] By that evening, a thunderstorm dampened the warfare, preventing further Dakota attacks.

Regular soldiers and militia from nearby towns (including two companies of the 5th Minnesota Volunteer Infantry then stationed at Fort Ridgely) reinforced New Ulm. Residents continued to build barricades around the town.

During this period, the Dakota attacked Fort Ridgely on August 20 and 22, 1862.[11][12] Although the Dakota were not able to take the fort, they ambushed a relief party from the fort to New Ulm on August 21. The defense at the Battle of Fort Ridgely further limited the ability of the American forces to aid outlying settlements. The Dakota raided farms and small settlements throughout south central Minnesota and what was then eastern Dakota Territory.

Minnesota militia counterattacks resulted in a major defeat of American forces at the Battle of Birch Coulee on September 2, 1862. The battle began when the Dakota attacked a detachment of 150 American soldiers at Birch Coulee, 16 miles (26 km) from Fort Ridgely. The detachment had been sent out to find survivors, bury American dead and report on the location of Dakota fighters. A three-hour firefight began with an early morning assault. Thirteen soldiers were killed and 47 were wounded, while only two Dakota were killed. A column of 240 soldiers from Fort Ridgely relieved the detachment at Birch Coulee the same afternoon.

Attacks in northern Minnesota

Settlers escaping the violence, 1862.

Farther north, the Dakota attacked several unfortified stagecoach stops and river crossings along the Red River Trails, a settled trade route between Fort Garry (now Winnipeg, Manitoba) and Saint Paul, Minnesota, in the Red River Valley in northwestern Minnesota and eastern Dakota Territory. Many settlers and employees of the Hudson's Bay Company and other local enterprises in this sparsely populated country took refuge in Fort Abercrombie, located in a bend of the Red River of the North about 25 miles (40 km) south of present-day Fargo, North Dakota. Between late August and late September, the Dakota launched several attacks on Fort Abercrombie; all were repelled by its defenders.

In the meantime steamboat and flatboat trade on the Red River came to a halt. Mail carriers, stage drivers and military couriers were killed while attempting to reach settlements such as Pembina, North Dakota, Fort Garry, St. Cloud, Minnesota, and Fort Snelling. Eventually the garrison at Fort Abercrombie was relieved by a U.S. Army company from Fort Snelling, and the civilian refugees were removed to St. Cloud.

Army reinforcements

Due to the demands of the American Civil War, the region's representatives had to repeatedly appeal for aid before Pres. Abraham Lincoln formed the Department of the Northwest on September 6, 1862, and appointed Gen. John Pope to command it with orders to quell the violence. He led troops from the 3rd Minnesota Volunteer Infantry Regiment and 4th Minnesota Volunteer Infantry Regiment. The 9th Minnesota Volunteer Infantry Regiment and 10th Minnesota Volunteer Infantry Regiment, which were still being constituted, had troops dispatched to the front as soon as Companies were formed.[13][14] Minnesota Gov. Alexander Ramsey also enlisted the help of Col. Henry Hastings Sibley (the previous governor) to aid in the effort.

After the arrival of a larger army force, the final large-scale fighting took place at the Battle of Wood Lake on September 23, 1862. According to the official report of Lt. Col. William R. Marshall of the 7th Minnesota Volunteer Infantry Regiment, elements of the 7th Minnesota and the 6th Minnesota Volunteer Infantry Regiment (and a six-pounder cannon) were deployed equally in dugouts and in a skirmish line. After brief fighting, the forces in the skirmish line charged against the Dakota (then in a ravine) and defeated them overwhelmingly.

Among the Citizen Soldier units in Sibley's expedition:

Captain Joseph F. Bean's Company "The Eureka Squad"

Captain David D. Lloyd's Company

Captain Calvin Potter's Company of Mounted Men

Captain Mark Hendrick's Battery of Light Artillery

1st Lt Christopher Hansen's Company "Cedar Valley Rangers" of the 5th Iowa State Militia, Mitchell Co, Iowa

elements of the 5th & 6th Iowa State Militia

Iowa Northern Border Brigade

In Iowa alarm over the Santee attacks led to the construction of a line of forts from Sioux City to Iowa Lake. The region had already been militarized because of the Spirit Lake Massacre in 1857. After the 1862 conflict began, the Iowa Legislature authorized “not less than 500 mounted men from the frontier counties at the earliest possible moment, and to be stationed where most needed”, although this number was soon reduced. Although no fighting took place in Iowa, the Dakota uprising led to the rapid expulsion of the few unassimilated Native Americans left there.[15][16]

Surrender of the Dakota

Most Dakota fighters surrendered shortly after the Battle of Wood Lake at Camp Release on September 26, 1862. The place was so named because it was the site where the Dakota released 269 European-American captives to the troops commanded by Col. Henry Sibley. The captives included 162 "mixed-bloods" (mixed-race, some likely descendants of Dakota women who were mistakenly counted as captives) and 107 whites, mostly women and children. Most of the warriors were imprisoned before Sibley arrived at Camp Release.[17]:249 The surrendered Dakota warriors were held until military trials took place in November 1862. Of the 498 trials, 300 were sentenced to death though the president commuted all but 38.[18]