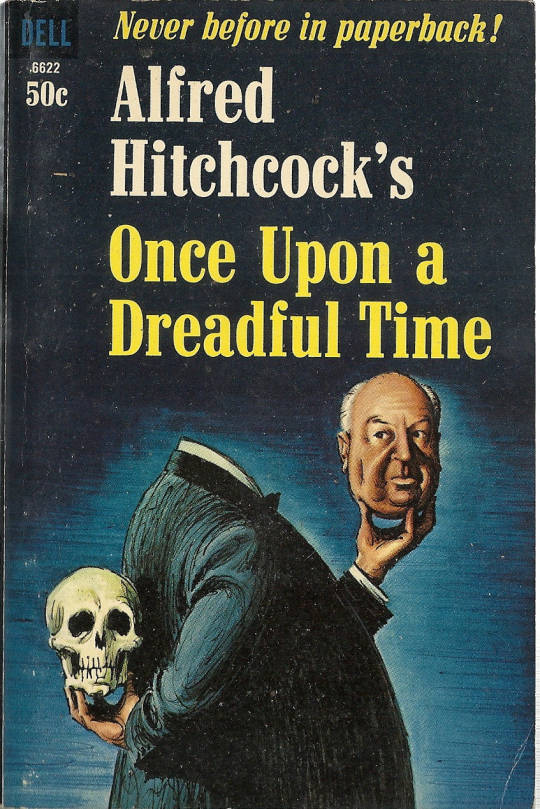

#Alfred Hitchcock's Once Upon A Dreadful Time

Text

Vintage Paperback - Alfred Hitchcock's Once Upon a Dreadful Time by Alfred Hitchcock

Dell (1964)

#Paperback Art#Paperback Cover#Alfred Hitchcock#Alfred Hitchcock Presents#Alfred Hitchcock's Once Upon A Dreadful Time#Mystery#Horror#Film#Television#TV#Dell Books#Dell#Skulls#1964#1960s#60s#Paperback#Paperbacks

160 notes

·

View notes

Text

January 21, 2021: The Wages of Fear (1953)

What exactly is a thriller, anyway?

Now, I’ve repeatedly considered having thrillers take up their own month, considering that they’re considered one of the core eleven film genres. However, they intersect so commonly with other genres, that I’ll be incorporating it into other months this year.

The definition of the thriller or suspense genre relies on surprise and intrigue. The audience is made unaware of certain information, giving a sense of mystery to the movie’s setting. The protagonist is often also unaware of these certain things, although that certainly isn’t a requirement.

Sometimes, they’re as innocent as the audience, if not moreso, and may be getting manipulated during the course of the story. Escapes, chase sequences, clear or hidden dangers, all of these meant to build suspense and unnerve the audience. It doesn’t have the overt scares of a horror film, and its action scenes build up to a feeling of building dread. They’re adrenaline-raising, heart-pounding, edge-of-your-seat films.

We’ve already covered one of the most prominent subgenres, the spy movie. We’ll cover more during Horror October, naturally, and a couple more this month. Comedy April’s even going to have a comedy thriller or two, while Romance February will pack an erotic thriller in there. Oh, and let’s not forget Crime July and Drama December. Like I said, they’ll be all over the place. Today, though, we cover one of the seminal French action thrillers, similar to our last two entries, but MUCH older. Enter Jean-Georges Clouzot.

Clouzot is one of the old-school French directors, even though he debuted quite late as compared to most, in 1942. A French Alfred Hitchcock, Clouzot’s first solo film was The Murderer Lives at Number 21. And surprisingly, it’s known as a comedy-thriller, and made a splash in theaters when it debuted in 1943. Which is interesting, given that whole World War II kerfuffle at the time. His most famous film, however, came in 1955, and was called Les Diaboliques. And THAT’S a psychological thriller that may end up on my list for October.

But two years before that, he made an action thriller. You know where this is going at this point, so let’s get on with it! SPOILERS AHEAD for The Wages of Fear!

Recap

Before we start, a tiny disclaimer: GIFs were...impossible to find for this one. HOWEVER, I miraculously found a recolored copy that I was able to convert into GIFs. I prefer the black-and-white version, which is how I watched it, but SACRIFICES MUST BE MADE

We start in Las Piedras, a small village in a Spanish-speaking country somewhere in Central America. A group of men speaking French, English, and Spanish are relaxing on a saloon porch, trying to beat the heat. These men include Mario (Yves Montand) and Bimba (Peter van Eyck). His girlfriend (?) Linda (Véra Clouzot, the director’s wife) works as a servant in the saloon.

Eventually, the men are told to leave, with Bimba being told to go to the airport to pick up mail. Arriving on the plane - other than a man with a whole-ass GOAT, which must have made for a fun flight for EVERYBODY involved - is a rich-looking man in a white suit and a fancy fly-swatter.

Our man, who’s French, runs into Mario, who is also French. This is Jo (Charles Vanel), who, despite looking rich, is out here looking for something monetary. Mario, after being weirdly cold to Linda, leaves for his home where he lives with Luigi (Folco Lulli), who speaks Italian. A real polyglot of a movie, this one.

Over the course of a montage of indeterminate time, we find out that there’s no work in this town for the various men, who are stuck in this town because of the desert surrounding it, expensive tickets, and no jobs or employment opportunities. We also find out that since there’s oil, there are Americans.

The Southern Oil Company, SOC, dominates the town due to nearby oil fields. They aren’t the best, though, and they tend to treat the townspeople pretty terribly. Jo inquires for a job there, to no avail, and reconvenes with Jo. After treating Linda and Luigi, to be frank, like ABSOLUTE shit, Mario...WAIT A GODDAMN SECOND

HOLY SHIT, MARIO AND LUIGI LIVE TOGETHER. REALLY?!? Holy shit.

Jo’s a dick, it turns out, which causes a rift between the two Frenchmen and the others. After literally getting the entire saloon angry with his antics, he threatens the nice Luigi with a gun, causing a tense atmosphere with everybody. After literally handing Luigi a gun to shoot him, the dejected man leaves the bar, dejected. Like I said...Jo’s an absolute DICK.

The next morning, something’s happened. The oil field has caught on fire, killing some of the residents who worked there. This causes some anti-foreigner rhetoric, which’ll probably spell trouble for our mostly foreigner cast. The foreman is Bill O’Brien (William Tubbs), who’s asked to handle the situation by his bosses. The only way to put out the fire is to generate an explosion triggered by nitroglycerin. Which seems...backwards, but I don’t know how oil works. They need to transport the nitroglycerin to the field, but the job is too dangerous for unionized workers. Therefore, the idea is formed to bring in some of the unemployed men, especially those that hang around the saloon. And, of course, that includes Mario, Jo, Bimba, and Luigi.

Speaking of Luigi, sad news. Looks like his construction job has resulted in cement powder depositing in his lungs, giving him 6 months to a year to live. Shame, he seems like a very nice guy. And so, considering that this job is dangerous, but follows a lot of money...he doesn’t have much to lose.

One of the people at the briefing immediately backs out upon learning about the job. He notes that this job infects men with fear that they can’t recover from. For that fear, the wages are $2500 per person. Only four people can do this job; two per truck, with one driver and one passenger. After some trials, Mario, Luigi, Bimba, and Smerloff, a German, are chosen. Jo isn’t good enough, much to his own dismay. However, as Bill and Jo are old friends of sorts, they make a deal; if one of the men doesn’t show up, Jo can take his place.

That night, the men (sans Jo) gather in the saloon. One young man, an Italian named Bernando who wasn’t chosen, gives Linda a note to mail to his mother. Sadly, there’s a reason for that that I won’t show here. But while they tell him that there’ll be a next time, he insists that their won’t be. I’ll let you fill in the tragic blanks.

The next morning, Smerloff doesn’t show up, having last been seen with, uh...with Jo. Wonder where Smerloff went. Well, predictably, Jo ends up replacing him. Jo and Mario go first, after winning a coin toss. They drive off hauling their truck loaded with nitroglycerin, and you can feel the fear begin to set in for Mario. As they drive through town, Linda tries to say goodbye, only for Mario to literally push her off the truck, MAN, I don’t like this guy.

As the truck drives, they encounter their first obstacle: Jo. As he’s driving, fear would appear to set in for him as well. He overcomes a couple of large puddles, but begins to shiver and sweat, saying that he’s sick. But no, he’s definitely just nervous, and they stop the truck in a forest of sugarcane so that Jo can take a break. However, they have to get going quickly, as the second truck is close behind them.

In the second truck, Bimba and Luigi talk a bit, with the affable Luigi doing most of that talking. But when Jo and Mario stop for a second time, they tell the pair off and drive past. Because of this, they hit the first real obstacle: a stretch of rough and bumpy road called the washboard. To get over it, one has to go 40 mph to get over the bumps. If not, then the truck will feel the bumps, and the nitroglycerine will explode. Luigi and Bimba get over with some difficulty, finding out that the gas in their truck contains water, and needs to be changed.

As for Jo and Mario, Jo’s nervousness costs them time and energy, as he refuses to speed up to the proper speed before getting on the washboard. They have to back up (inside their own tire tracks), and Mario officially takes over the wheel. And he starts going fast...too fast.

They almost collide with the other truck, but Luigi and Bimba speed up in time. Next obstacle: a road under construction. A K-turn is needed, and that turn requires a flimsy wooden construction to be driven on. It isn’t easy, the very competent Luigi and Bimba manage it all right. Jo and Mario get there, and Jo, predictably, FREAKS OUT.

Mario, on the other hand, is overly reckless. In order to get over the rotted out road, Mario has to drive to the very edge of the construction. Jo, who was guiding him from the back of the truck, ends up tumbling over the side. While Mario thinks he’s dead, Jo instead takes the opportunity to straight-up run away, although Mario does see him. This is a problem, as the truck begins to slide on the wood without Jo’s help. But Mario, ever-resourceful, figures it out. But...

OH SHIT! Mario gets off the construction just as it’s starting to collapse. He makes it forward, and passes the cowardly Jo, who tries to get back onto the truck.Mario, UNDERSTANDABLY PISSED, almost leaves him behind, but finally stops so that he can get rejoin. The two get into an argument, where Mario calls Jo out for once being brave, but now being a coward. Jo tells Mario that he has no imagination, and that Jo’s “died fifty times since last night.” I love that line, honestly.

Back to Luigi and Bimba. They talk about life after the money, even though we’re aware that Luigi doesn’t have much of that left. It’s then that the next obstacle appears: a talus slope, from which a giant rock has fallen, and blocks the road. Bimba has the...bright idea (?) of using the nitroglycerin to blow up the stone. Which I feel like is an...idea.

They make a hole in the rock, then siphon some nitro out of a container. The others catch up, and back the trucks away, leaving Bimba by himself to do the deed. And it is...ABSOLUTELY NERVE-WRACKING HOLY SHIT. After setting up a Rube-Goldberg device and pouring the nitroglycerin into a hole in the rock, Bimba lights a fuse and sets it to blow.

But because they fear they;ve parked too close, Luigi runs back to put out the fuse! Too late, though, as the nitro blows, and rocks fly, almost falling on the trucks in the process. As for Luigi...he survives! Knocked out by the shock from the explosion, but not injured. In the process, the rock is finally destroyed, and Mario and Luigi finally reconcile as friends.

Back on the drive with Luigi and Bimba! We find out that Bimba’s a German, whose parents died at the hands of the Nazis. He himself was in a work camp for 3 years, which is why he is as brave as he is. Behind them, Jo and Mario talk of France, and Jo rolls a cigarette.

...FUCK.

Luigi and Bimba are gone. Like that. This, of course, freaks out Jo, who runs away from the truck. Mario catches up, and beats Jo for his cowardice. They return to the truck, albeit very reluctantly on Jo’s part. They make it to the site of the explosion, where there’s...no sign. No sign of the truck, of the guys, nothing. Just a busted pipe spitting up oil, creating a massive puddle.

Jo goes into the shallow pool to guide Mario through it, but gets stuck in the pool in the process. Mario runs over his leg, and the truck itself gets stuck in the oil. Mario gets out of the truck and helps Jo, whose leg is FUUUUUUUUUCKED up. I mean it, it’s like a busted sausage link, like a sock made of MEAT. It’s not OK, is what I’m saying.

Mario, using a cable, an iron rod, and his wits, manages to pull the truck out of the oil pool. He gets Jo, and the drive continues. Jo, in pain and possibly bleeding out, is close to falling asleep. To keep him awake, the two talk about Paris. Day turns to night, and Mario continues to drive. They finally make it to the burning oil field...but too late for Jo.

Mario’s finally able to get out of the truck, and stumbles towards the fire and collapses. Not dead, just exhausted. He gets all of the money promised to the four, and leaves in the now empty truck to go back to Las Piedras. Free of nitroglycerine and free of fear, he gleefully drives back. In the saloon, the patrons celebrate Mario’s survival while listening to Blue Danube, and so does Mario! And Mario is driving...carefree. And recklessly.

...That’s The Wages of Fear. See you in the Epilogue.

#the wages of fear#le salaire de la peur#henri-george clouzot#yves montand#charles vanel#folco lulli#peter van eyck#action thriller#365 movie challenge#365 movies 365 days#365 Days 365 Movies#365 movies a year#user365#my gifs#mygifs#moviegifs#action january

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Once Upon a Time In Hollywood The Catharsis Of Release

Once Upon a Time In Hollywood was not my favorite film of 2019 but it's ending was definitively the one I found the most satisfying and in a year of great finales that's saying something. Tarantino's ode to Hollywood managed this by edging the audience for nearly the entirety off its 2 hour and 40 minute run time, which only made the pay off all the sweeter.

There's a famous quote by Alfred Hitchcock, where he talks about the difference between suspense and surprise in movies. He uses the example of a bomb beneath a table, stating that if you show your audience a bomb going off on screen the audience only gains 15 seconds of surprise. Now should you want to leave your audience in suspense he instead suggests that you let your audience know that there is a bomb and that it will explode in 15 minute's, that's 15 more minute's of suspense.

In Once Upon a Time In Hollywood, Sharon Tate is first shown roughly 3 minutes into the movie, a minute or so later we see out first time stamp, Saturday February 8th 1969. We as the audience know that Sharon Tate was murdered on the night of August 8th 1969, this is our bomb and we now know it has 6 months until it goes off, the only thing we don't know is how is Tarantino going to go about it?

Now Sharon Tate is not our main character, she is a essentially a side character who's entire purpose is to remind us of what is going to happen. Our main focus is on Rick Dalton and his stunt double Cliff Booth, they are who we really get to know and they're very enjoyable to watch. So enjoyable in fact that often times in the movie you might forget what's happening in the background, you might get a little too comfortable but every time you do something will pop back up again to keep you on your toes.

Enter the Manson clan. They don't turn up until 15 minutes in and when they do they appear eerily singing and they search garbage cans for food. In any other movie we might just believe they are regular bunch of hippies trash diving but this is Tarantino and this is no coincidence. These ones are all girls and one in particular is tall, slim and rather pretty and when we see her flash the peace sign at Cliff Booth I couldn't help but feel a sense of dread. They too are background noise but noise that steadily gets louder the more we try to block it out.

The movie follows the slightly washed up careers of both actor and stuntman, they are shown to be more friends than boss and employee and we grow to like and root for both a great deal. Meanwhile Tate in her brief moments is shown to be happy, full of life and in her prime, we don't want anything to happen to any of these characters (Most especially to Tate who was very much real). Tarantino has been shown to be unafraid to both kill off main characters and rewrite history, as the story progresses we have no idea how exactly he will change history if he will at all, all we have is our time stamps slowly counting down the days to August 8th.

Half way through the movie we see Cliff Booth pick up a hitch-hiking Pussycat, this being the hippie he has seen a few times throughout the movie. When he offers her a ride the uncomfortable feeling from before is back, this girl is trouble and she wants to be dropped off at Spahn Ranch, a known home for members of the Manson family. Of course Cliff Booth doesn't know that, but it's clear he thinks something shady is going on and as his old colleague George Spahn owns the ranch he can't help but feel the need to check in on him.

This leads to probably the most tension filled scene in the movie, we see him roll up with Pussycat, who is eager to show him off to the other members, they are far more wary of this stranger, even going so far as to have one of their members, “Tex” check him out. This first encounter could end badly should he screw up and we know it. Luckily Cliff is smart and he knows what to say to get the all clear, we previously heard Pussycat yell at some Cops, Cliff is quick to mention that he once spent some time in Texas busting up some Cop shows. Tex is appeased enough to leave him be and as soon he's gone Cliff shows his true purpose for being there, he knows George Spahn and he will not leave without seeing him.

The clan members suddenly aren't so friendly and make excuses but he will not be dissuaded, it takes some convincing but he eventually gets permission to enter George's home. He has one last glance back before he enters the property and we pan to some unhappy looking hippies and we feel worried for what might happen in that house because we know what these people were capable of and whether of not Cliff might find George dead. It's discovered that George is in fact alive and gave the members permission to be there and we breath a sign of relief, although can't help but feel George is being taken advantage of.

Mission accomplished all we care about now is Cliff getting out of there and he tries to leave walked past the yelling and jeering clan members and comes close to freedom but his getaway is damaged. One of the Mansonites “Clem” has burst one of Cliff's tires leaving him stranded, Cliff tells him to fix it and when he refuses he proceeds to beat him bloody until he agrees. This spurs one the others to send for Tex to return and help them, once again we are face with a time limit. The car has to be fixed before Tex gets back and we anxiously hope it is, seeing Cliff speeding away seconds before Tex returns is the final relief in a scene full of suspense, for now he has gotten away.

We then return the focus to our main duo for a while, building slowly to our climax. The final part of the movie is a culmination of what we have been waiting for. We are finally shown the date August 8th 1969. This night we follow both Cliff and Rick as well as Tate, Sebring and the others, out time stamps are now counting down the clock by minutes rather than dates and we can feel the tension building. Eventually our cast return home and we hit 12:03 with Cliff and his dog Brandy also being at Rick's house.

The events that follow are where we see history truly diverge when the Manson members who killed Sharon Tate and the others arrive they are confronted by a drunk and irritable Rick Dalton who yells at them for being there.

This is where the Mansonites decide to change course and go after the Dalton house instead, this is where our pivotal moment finally hits, this is where our bursting balloon of tension slowly starts to leak air. Rick has chosen to drink margaritas with his headphones in his pool, his wife sleeps in the bedroom and Cliff has smoked his acid cigarette whilst walking Brandy and is now tripping in the kitchen. Whilst Cliff attempts to feed Brandy she begins to growl at the door, Cliff slowly catches on and heavy dog food can still in hand he faces the door which is soon slammed open, Tex enters wielding a gun and we now await with baited breathe how Tarantino will play this out. They exchange a few words and a very at ease Cliff eventually recognizes them as the Hippies he met before, despite the odds being 3 to 1 everything we've seen so far has pointed to Cliff eventually coming out of top we start relax too. Moments later a frustrated member yells out “Shoot him Tex!” this is Cliff's cue, with a mouth click Brandy his well trained canine leaps into action grabbing the gun wielding arm in her jaw. Finally the balloon has burst, the bomb has gone off and what follows in some of the most gratifying movie violence I've seen in a long time.

It's brutal and bloody and completely cathartic, this whole insane tension filled ride is coming to a close and it truly goes out with a bang. In any other movie had this just been a home invasion such a scene would be over the top but Tarantino used reality to fuel our anger, we know exactly what monstrosities these people were going to commit and so we feel only relief at their harsh punishment.

This finale was truly glorious and I enjoyed it immensely, the movie ends quietly with a slightly injured but victorious Cliff going to hospital and an in shock Rick going up to meet his (still thankfully alive) neighbors. We can rejoice in this fairy tale ending and forget for a moment the sadness that reality did not go the same way. Once Upon a Time In Hollywood was an intense movie, that never let you forget what was coming and it's been a long time since I've felt such a release of tension in any movie so for that Tarantino I thank you.

#once upon a time in hollywood#2019#quentin tarantino#tarantino#movie essay#catharsis of release#movies 2019#movie analysis#movie tribute#movies#film#cinema

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Marathon #2: Horror

With the successful wrap of the Western Marathon, it is time to turn our attention to the Horror Marathon - and boy, am I nervous about it! I am not a huge Horror fan and tend to avoid these films whenever possible - but that time is over as I dive into Filmspotting’s next marathon, focusing on the Horror genre. I started off this journey through the safest possible route - reading “The Horror Film: An Introduction” by Rick Worland - an academic text of the genre’s history that also traces the societal context that was reflected in and also shaped by the genre. In this introduction, I will touch on the basics of the genre, summarize the history, explore my own experiences with Horror films, and lay out the list of films we will be watching. Here I go - holding my breath in suspense, closing my eyes in terror, and tiptoeing towards the Horror!

To start at the beginning - what defines a Horror film? At the basic core, a Horror film is intended to provoke an emotional response from the viewer - to shock, disgust, scare, and (in the truest essence of the word) to horrify. This is accomplished through the mise-en-scene of the film - the settings, iconography, and also the themes. A vital component of this package is the villain of the piece - the Monster! Whether a grotesque figure featuring heavy makeup or a regular human maniac, the monster is a violation of regular society and true nature; they must be fearsome and repellent, attacking the normal life of the heroes and seeking to destroy their victims (and oftentimes the domesticity surrounding those protagonists). Early in Horror history, pulling from Gothic trappings, the settings were often sites where monsters would credibly dwell - a decaying haunted house where ghosts still reside, a scientist’s lab where experiments go wrong, or creepy cemeteries where the dead rise to pursue the living. Later on, the settings expanded into “normal society” locations - a small-time hotel, the suburban house, or other teenage hangout spots. The iconography that goes along with these settings are hallmarks of nightmares - the overwhelming shadows, an offscreen terror that is creeping closer, the victims intense scream or look of dread. The early era of Horror featured monsters that were external threats to society and the institutions (church, police, state) were all helpful to the protagonists, who were characters worthy of saving. Once the turbulent 1960s gripped the United States and Hollywood as a business and artistic center began to change, the Horror genre transformed as well - the monster could now come from society itself, plots referenced the decay and breakup of the American family, and an overall questioning of normality and tradition was commonplace. Finally, the genre began to direct its films toward a teenage audience, especially attempting to entice potential youthful ticketgoers with stories centered around sex and violence. In contemporary times, the latest development in the genre revolves around how special effects can escalate the production of gore and the enhancement of the grotesque to even higher levels of mayhem.

Horror films have their roots in Gothic literature and were first popularized in Germany in the 1920s, when the German Expressionism style gained momentum. Films such as The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920) and Nosferatu (1922) established much of the iconography and early themes for the genre. Many of the film directors and artists left Germany, lured by the opportunity to influence Hollywood and it’s take on the genre. Universal in particular specialized in Horror films - an early cycle during the 1920s with films like The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1923) and The Phantom of the Opera (1925), both featuring the first Horror star Lon Chaney. Universal’s second Horror cycle took place in the 1930s, utilizing the talents of Bela Lugosi and Boris Karloff; classic films like Dracula (1931) with Lugosi and Frankenstein (1931) and The Mummy (1932) with Karloff were significant milestones cementing the legitimacy of the genre in popular culture. The genre was less prominent during the WWII years and was overshadowed by Science Fiction during the 1950s (although Roger Corman and Vincent Price both got their start during this time making low-budget teen exploitation Horror films), but made a sharp comeback in the 1960s and into the chaotic Vietnam War era in America.

Many scholars point to the Alfred Hitchcock film Psycho (1960) as the titular movie in the Horror genre’s shifting viewpoints about the larger society. As noted above, pre-1960s Horror films ended with the destruction of the monster, which brings a sense of closure to the unnatural element it had inflicted upon the characters and society. Once Psycho had established that the villain could be a madman that emerges from society itself and, combined with the turbulent Vietnam and Cold War eras, the institutions once worth preserving were now suspect and even working against the protagonists of Horror films. These themes became even more exaggerated in the 1970s and the rise of the slasher/stalker films (which will be the focus of this Horror Marathon). Filmmakers that grew up as fans of the previous generation of Horror films (and the fan magazines that sprung up in popular culture as well) began making their own versions of the genre in the 1980s and 90s; Steven Spielberg, Brian De Palma, John Carpenter, George Romero, Francis Ford Coppola, Terry Gilliam, and M. Night Shyamalan working with major studios all took their turn at directing Horror films, partnering with makeup artists and special effects masters to heighten the terror. Independent studios also took on the low-budget Horror flick, aimed at the teenage audience, with films like Evil Dead (1981), Scream (1996), and I Know What You Did Last Summer (1997). As the Horror genre entered into the new millennium, the films took on a postmodernist trend - showing awareness of the genre’s history, tropes, and plot conventions - and sometimes even commenting on it for additional screams or for comedic laughs. While the genre has evolved, its core tenant of scaring the bejeezus out of the audience has never strayed from its mission.

Personally, I actively avoid Horror films, whether screening in the theater or watching at home. I have seen exactly zero of these films included in the Marathon and would never have actually pursued them without taking on this challenge. I spent some time reflecting on why I have an aversion to the genre and it comes down to not wanting to actively subject myself to the feeling of fear, which is literally the base intent of Horror. Images of gore (which I usually glimpse through the slits of my fingers covering my eyes) aren’t as terrible for me as the atmospheric suspense; the former I can tell myself is not real and just movie magic - but the monster stalking the woman in the dark or the slow creaking of a door opening or the anticipation of an attack in a rain-soaked alley - these all could be real events!

Over my life, I have watched a few Horror films that have stayed with me. My most vivid memory is watching The Ring (2002) in high school. I went with a group of friends and drove a few of them home. To get back to my house, there was a backroads way that went through wetlands with limited streetlights - so after an extremely suspenseful and scary movie, I drove home through a dark and winding road that was just PERFECT for something creepy to attack me. Thank goodness I made it home ok! Another Horror film that I watched during high school had the opposite of the intended effect - I went to a party where The Exorcist (1973) was screened; chatting with friends, half paying attention to the film, and not truly connecting to the material meant that when the famous head spinning scene happened - laughter rang out amongst all my friends. An entirely different atmosphere surrounded my screening of The Shining (1980) - I was living alone, watching it late at night, and had to pause the movie halfway through and call my Mom to distract me from the growing dread in the pit of my stomach. And my final notable Horror viewing experience was when I began this blog; I watched Nosferatu (1922), one of the original Horror movies filmed in the German Expressionism style. This film was less terrifying and more atmospheric - and I certainly appreciated the filmmaking techniques employed to create the vampires creepy style and tone, despite being so early in film’s history.

I thoroughly enjoyed reading “The Horror Film: An Introduction” because I could enter into the genre through a historical and societal lense, taking an academic approach to an otherwise scary venture. Out of the vast canon of films that have been produced in the genre, this Marathon is only taking a small slice from the 1970s and 80s - primarily looking at the slasher/stalker cycle. It also includes two sequels, so I will be including two additional films as homework to screen before those official entries, although they will not count towards the awards at the conclusion of the Marathon. Here are the films I will be cringing, flinching, and screaming at during Gibelwho Production’s Horror Marathon:

1[a]. Night of the Living Dead (1968), George Romero

1. Dawn of the Dead (1978), George Romero

2. The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1974), Tobe Hooper

3. Suspiria (1977), Dario Argento

4. Halloween (1978), John Carpenter

5. Re-Animator (1985), Stuart Gordon

6[a]. The Evil Dead (1981), Sam Raimi

6. Evil Dead 2 (1987), Sam Raimi

Watch your back and happy haunting!

#night of the living dead#dawn of the dead#the texas chainsaw massacre#suspiria#halloween#re-animator#the evil dead#evil dead 2

0 notes

Text

thoughts on the BIRDS!

whats new buttheads!

bout to do another post! currently x men: wolverine origins or sum shit is playing in the background. super loud. are these movies well regarded? also just watched the new riverdale but that’s a whole other can of worms.

i am in a really bad class on a really cool subject! it is called “film as a mass medium” but we only talk about adaptation but on like a really boring redundant surface level? so like we read the books then watch the movies or what have you. and then in class it’s just like what DEFINES a nested narrator, medium specificity, and all this lame fucking shit! however, we wrote midterm essays last week and i had fun writing this thing on daphne du maurier’s novelette The Birds (1952) and Alfred Hitchcock’s 1963 adaptation with Tippi Hedren.

I wrote it very very quickly and was late handing it in so my thoughts are kind of a little bit scattered but i think i wrote some cool things too. also the citations are like most definitely fucked up but.... whatevs. i think i was probably supposed to talk more a/b like what entailed the changes in the narrative in the adaptation with regards to like medium specificity or some shit like that but lol no thank u sir!

the essay q was about like causalities for the phenomenon of the birds and like whether there was 1 and did it matter in the first place

Bombings, Bombshells, and Postwar Disintegrations of Order

Allegories of Chaos in The Birds (1952, 1963)

World War II represented, in midcentury thought, a break in conventional standards of morality, stability, and order. While no single, cohesive Copernican shift can be perceived amidst the proliferation of postmodern discourse, responses to the rapidly changing world articulated confusion, dread, and excitement for a society in flux (Sim). In both Daphne du Maurier’s 1952 novelette, The Birds, and Alfred Hitchcock’s 1963 film adaptation of the same title, the phenomenon of the bird attacks is given no rational explanation in the narrative, but the ensuing descents into chaos in both works allegorically reflect popular anxieties of the two works’ respective contexts. Du Maurier’s novelette, written a mere seven years after the Allied victory in World War II, offers a figurative reimagining of the 1940 German Blitzkrieg attackson London, focusing on a disintegration of community and psychological stability in rural England. Hitchcock’s film adaptation, on the other hand, produced ten years after du Maurier’s, and operating in an American Hollywood context, is also intentionally ambiguous in terms of a credible diegetic cause for the attacks in Bodega Bay. However, the film’s collapse of small town life, and its attendant conservative values, can be attributed to the arrival of Melanie Daniels, whose character embodies an empowered, urban concept of femininity, a new fixture of the 1960s with the rise of second wave feminism. Du Maurier’s source material and Hitchcock’s film adaptation effectively unsettled viewers at their times of production due to their reflections of relevant anxieties, reaching backwards, forwards, and across oceans for inspiration.

The premise of du Maurier’s novelette, namely, the sudden plagues of violent birds suddenly descending upon England, proceeds in the narrative without being granted a credible cause, although various causes are speculated. At times, Nat declares that the birds must be foreign to the land, descended from “upcountry” (du Maurier 4), claims their violence was incited by “fright” (du Maurier 5), and repeatedly blames the circumstances on weather, while Jim posits that perhaps they were hungry (du Maurier 7), and the national news suggests a vague relationship to the “Arctic airstream,” (du Maurier 9). The townspeople at first doubt the legitimacy of Nat’s story after the first night, laughing at him and planning to shoot the birds away. Daphne du Maurier’s characters in the novelette are fraught with this persistent confusion and misinformation. Nat, in his grave stoicism and “solitary disposition” (du Maurier 1), is viewed by the townspeople he encounters as an alarmist and a drunk (du Maurier 6). As the narrative proceeds to legitimize the phenomenon for the general public, with national news broadcasts declaring emergencies and the deaths of secondary characters, Nat’s wary perspective is likewise given credence. His character becomes the voice of reason, as opposed to an imaginative farmhand. This moment of transition in his character arc, coincidentally occurring once all characters apart from his immediate family have receded from the narrative, marks a shift toward recognition of the birds as analogous to a previous event in recent history, the air raids carried out by the Germans in 1940.

The Blitz, a principal event in the Battle of Britain, wreaked havoc across the nation for a duration between four and thirteen months, depending on the historical source. Concentrated in London, targeting the Royal Air Force base, the violence extended across the nation. The Nazi forces (Luftwaffe) sought to destroy British infrastructure with a particular inclination toward buildings related to the war effort. Although the Luftwaffe was technically indoctrinated against targeting civilians, the large scale bombings made civilian casualties unavoidable. Britain would go on to win a decisive victory, rebuffing the onslaught of German bombings, but the widespread destruction of infrastructure and civilian casualties would leave behind a legacy of psychological trauma (Overy).

Du Maurier’s novelette proceeds quickly towards its premise, revealing little of its characters’ previous. However, a crucial fact is given concerning the protagonist, Nat, and his personal history. This insight serves to explicate Nat’s employment: “(he), because of a wartime disability, had a pension and did not work full time…” (du Maurier 1). Nat’s status as a military veteran is essential to the film’s wartime allegory. Written in 1952, it can be assumed that the story’s protagonist is a veteran of WWII, and, particularly due to his being injured in the conflict, would be a likely victim of lingering psychological effects of the extreme violence, perhaps even Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (Overy). While this psychological trauma is never directly addressed in the narrative, Nat’s psychological states are the subject of much narration throughout. His aforementioned preference for solitude, despite being a married man, is a general indicator of instability, as well as the townspeople’s initial hesitance to take his story about the bird attacks at face value, and the children’s laughing at his seemingly bizarre behavior at the bus stop (du Maurier 13).

As previously mentioned, although Nat’s status as an unsociable, disabled war veteran leads the townspeople to initially view his warlike stories about the birds with skepticism, after his tales are legitimized publically, and related metaphorically to the Blitz, his seasoned perspective is privileged as useful to himself and others. His instincts for danger, presumably gained in war, are addressed in description of Nat’s experience the night of the first attacks: “(Nat) leaned closer to the back of his sleeping wife, and stayed wakeful, watchful, aware of misgiving without cause,” (du Maurier 2). Although the reader is privileged much insight into Nat’s heightened sense of awareness for the impending crisis, it is not until the bird attacks are metaphorically linked to the Battle of Britain that Nat becomes the narrative’s lone safeguard against total destruction. He later ponders: “It was … like the air raids in the war. No one down this end of the country knew what the Plymouth folk had seen and suffered. You had to endure something before it touched you,” (du Maurier 7). As the bird attacks increase in severity and scale, Nat’s wealth of wartime knowledge proves progressively more valuable. His history with the Battle is emphasized throughout the narrative, and renders him more equipped to deal with the similar psychological effects caused by the birds’ torments. Akin to Plymouth, devastated repeatedly by the Blitz, the story’s location in Cornwall is a coastal archipelago. Likewise, the effects underwent by Nat, his family, and the other townspeople are comparable to the experiences of Plymouth civilians during the Blitz. The farmer relays that he heard a rumour implicating Russian culprits, “They’re saying in town the Russians have done it. The Russians have poisoned the birds,” (du Maurier 15). While this conjecture is given no credibility, it is reflective of the early Cold War anxieties rising to prominence in the 1950s. Nat understands that isolation from urban centres renders rural communities more vulnerable but also safer in their remoteness. He declares: “...whatever ‘they’ decided to do in London and the big cities would not help the people here, three hundred miles away,” (du Maurier 11). The uncertainty, lack of reliable vital information, disconnect from federal government, paranoia, and incessant posturing of false intelligence underwent by the citizens of Cornwall are all conspicuously reminiscent of the psychological effects of air raids on citizenry during WWII (Overy). Daphne du Maurier’s The Birds gives no narrative explanation for the violent phenomenon of the bird attacks. Instead, the novelette seeks to expose the futility of rationally explaining such senseless violence. The work’s allegorical connection to the Battle of Britain culminates in no triumphant, patriotic resolution for England. Rather, it uses the imaginative framework of the bird attacks to explore the necessity of remembering the past when confronting the future, particularly in the face of inexplicably collapsed order. Concern for the cause of the phenomenon is thus subordinated to the need for informed pragmatism in mediating consequences, gained by remembrance of history.

Akin to its literary antecedent, Alfred Hitchcock’s film narrative likewise eschews a scientific causal force behind the bird attacks. Rather than the conjectural answers with which the citizens of Cornwall seek to rationalize the arrival of the birds, however, some people of Bodega Bay initially engage in incredulous denial, whereas others simply seek to mitigate without questioning. The denial is exemplified in the confrontation, beginning at 1:16:32, between Melanie Daniels and ornithologist Mrs. Bundy, who refuses to believe that such harmless creatures as birds could be responsible for the apparent violence. She declares, with an air of cold, scientific superiority: “Birds are not aggressive creatures miss, they bring beauty into the world. It is mankind, rather, who insists upon making it difficult for life to exist upon this planet,” (Hitchcock). Aside from this scene, occurring mere minutes before the largest bird attack yet witnessed, the characters of Hitchcock’s adaptation are largely preoccupied with mitigation rather than rationalizing or verifying, and thus the subject is given little direct attention. Another such example, however, in which a character is overtly concerned with causality, gives insight into the film’s larger allegory. The sequence beginning at 1:28:39, with the hysterical mother’s confrontation of Melanie, opens the door to the film’s complex response to modern femininity. The mother rants through tears: “Who are you? What are you? Where did you come from? I think you’re the cause of all this, I think you’re evil,” (Hitchcock). There is a degree of credibility to her reading of the coinciding of the bird attacks and Melanie’s arrival in Bodega Bay, although it goes unacknowledged by any other characters.

The arrival of Melanie is tied to the phenomenon of the birds, if only by coincidence, which consequentially links her presence to the disintegration of small town insularity and stability. She repeatedly butts heads with the conservative townspeople of Bodega Bay, most notably in the aforementioned instances, with the elderly, vaguely aristocratic British ornithologist, and the overly concerned, borderline hysterical accusing mother. The conflict of Melanie versus Bodega Bay is heightened to the level of political allegory by the conflation of her character with an urban concept of postmodern, liberated femininity (Burkett) in opposition to the more conservative values of the small town. As she further penetrates into the community (first to drop off lovebirds, next to stay with Annie, then to attend the birthday party, etc.), and her relationship with Mitch develops, the attacks intensify. Although the viewer is given little background information on Melanie’s character, Mitch reveals in the opening scene that she has been in court for counts of vaguely mischievous activity, and later that her wayward behavior in Rome had been the subject of popular gossip. He accuses her, “The truth is you’re running around with a pretty wild crowd...” (Hitchcock). Melanie Daniel’s character is known to the townspeople, including Lydia, as an unruly, even immoral, product of urban living. She stands in for the controversial rise of second wave feminism in the 1960s. The feminist thought of Hitchcock’s time placed revelatory emphasis on women’s sexual liberty and equal treatment in the workplace (Burkett). These radical changes in postmodern concepts of femininity were not met without resistance from conservative voices, and the polarization helped to shape the urban/rural bipartisan divide. Melanie’s own embodiment of the new iteration of feminist thought takes the shape of her own activities in the workplace, and her allegedly nude misbehavior in Rome. The violence that the birds bring to Bodega Bay ensues from the sewing of Melanie, a modern, empowered woman, into a small town, conservative community.

Mitch’s role in this process, however, may not be understated. He trivializes her experience with empowered femininity, chastising her unruly behavior while laughing at her occupational status. From the first scene, he exercises domineering power over Melanie. He tricks her at the pet store, invites her to dinner, asks her to stay the first night and subsequently schemes to get her to attend his sister’s birthday party, despite her insistent protests to return to San Francisco. His sentiment in this evident containment of Melanie’s strong femininity is illuminated in a line from the first scene. After ensnaring an escaped canary in his fedora, an antiquated signifier of dominant masculinity, he mysteriously says: “Back in your gilded cage, Melanie Daniels,” (Hitchcock). In defiance of both the dangers posed by his hometown’s ornithological predators, as well as Melanie’s own wishes, Mitch chooses to not only remain in Bodega Bay himself but to also contain Melanie in the hostile context, and eventually he literally seals her, along with his mother and daughter, in his childhood home. Throughout the film, Mitch Brenner connives to contain Melanie, with her empowered femininity, within a context both physically and figuratively inhospitable to her. She is only allowed to escape once she has been nearly killed by the birds upstairs, in an essentially suicidal decision which reads as an attempted martyrdom for second wave feminists. Surviving the onslaught, the family and Melanie evacuate Bodega Bay, driving through droves of stationary birds towards a distant sun peering through the clouds, evocative of the precarious balance and peace between rural and urban moral divisions, perpetually on the brink of violence.

In collective social consciousness, the unprecedented violence of World War II heralded a new age of ontological uncertainty. Responses to this historical rupture ranged from a newfound hope in the dismantling of oppressive societal conventions, to a fear for the violent potential of mankind. Produced nine years apart, Daphne du Maurier’s novelette, The Birds and Alfred Hitchcock’s film adaptation seek to depict a senseless breakdown of natural order, signified by the bird attacks. Whereas du Maurier’s literary antecedent represents the psychological implications of aerial warfare seen previously in the Battle of Britain, Hitchcock’s adaptation posits the disintegration of order as being inextricably tied to the collision of rural conservatism and the urban feminism of the 1960s. In neither film nor novelette is the phenomenon of the attacking birds given credible causal explanation, as both works question the human impulse to rationalize senseless violence.

0 notes