#ARCADI LITERATURE

Text

Books I Read in April

Reviews under the cut

Tom Jones by Henry Fielding (7/10)

This one was for class, and it was insane. First of all, it's over 900 words, so it goes on for a while. Second of all, this is a soap opera in the form of an 18th century novel. It's got children out of wedlock, a romance between people of different classes, a secret birthright, and lots of sex. Yes, sex, in an book from the 1700s. This book is notably a satire, and it pokes a lot of fun at the sanitized public image of the time. Also, it's getting a miniseries adaptation at the end of the month that looks really good.

Spell Bound by F. T. Lukens (8/10)

Overall, I just found this book good. It was a quick, light, easy read, and it's definitely a welcome reprieve from the intense fantasy I normally read. The magic is pretty fun, and I really liked the romance. The plot was a little too much for so quick a book, and some of the side characters aren't as fleshed out as I'd like, but this is definitely a great book to just relax and blow off some steam while reading. It isn't a masterpiece, but I'd still recommend it, especially if you're just looking for a little fun.

Alanna: The First Adventure by Tamora Pierce (9/10)

Part of my Tamora Pierce marathon, I very much enjoyed my reread of this book. I like the way Pierce skips through a lot of time; it brings a sense of realism to the whole thing as Alanna is training for years. I love Alanna's character development, and we have the start of it in this book. I will note that the plot feels a little disjointed.

In the Hand of the Goddess by Tamora Pierce (10/10)

In my opinion, this is the best book in Song of the Lioness. The character work with both Alanna and her love interests is great, the plot is cohesive, and you're on the edge of your seat. I'm a huge supporter of George, but why does their age difference have to be seven years??? It's a good thing Pierce can write some amazing romance.

Silver in the Bone by Alexandra Bracken (8/10)

Initially, I was having some trouble getting through this book. I think part of it was just how busy I've been, but I do think the beginning just doesn't do it for me. However, it was necessary for the most part, and I really liked the rest of the book. Tamsin grew on me, I was invested in the romance, and the side characters are quite good. The actual plot is full of all kinds of twists and reveals, and it ended on such a good cliffhanger—it definitely makes me want to read the next book! I'd say that even though this book isn't perfect, it's a great read, especially if you're an Arthurian nerd like me.

The Woman Who Rides Like a Man by Tamora Pierce (7/10)

Quickly following the best book of the series is, in my opinion, the worst. The actual character work and writing is just as good as Pierce's other books, but the subject matter is...touchy. For a book published in the 80s, it's already great that the Middle Eastern-esque culture is not just immediately villainized, but through a modern lens, the plot feels very white savior. Alanna has a great amount of respect for the Bazhir, and some of her preconceptions are disproven throughout the book, but her repeated aversion to the veils and Jon becoming the Voice just doesn't sit right with me.

The Castle of Otranto by Horace Walpole (5/10)

What an insane book. Another one for school, and this is the beginning of the genre of gothic literature. As such, this sort of story is finding its feet, and this one is all over the place. Due to some influence from medieval romance, the characters are all rather flat, but at least it's entertaining.

Dragonfall by L. R. Lam (9/10)

I'm really glad I got an ARC of this book because I really enjoyed it! I particularly liked Arcady, Everen, and their relationship, but the plot is solid and interesting, and the writing does something new. The only downside to this is that it's going to be at least a year before the next book comes out. While there's some intense cliffhangers at the end of this book, I don't really know how the next one is going to go, and I am very curious. In the meantime, I do recommend this book, especially for anyone looking for a slow burn fantasy romance with a bit more substance to it. And dragons, which is a good enough reason alone to read any book.

#books#wrap up#tom jones#spell bound#alanna the first adventure#tamora pierce#silver in the bone#in the hand of the goddess#the woman who rides like a man#the castle of otranto#dragonfall

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

In literature, what are some classic examples of The Arcady being portrayed as a refuge for characters seeking solace?

The term "Arcady" conjures images of an idyllic and utopian landscape, a realm of timeless beauty and tranquility. The Arcady Showflat word, rooted in ancient Greek mythology, has transcended its origins to become a symbol of an earthly paradise, a place where nature and humanity coexist harmoniously. In literature, art, and the collective imagination, Arcady has served as a source of inspiration for centuries, offering a vision of a simpler, more pastoral existence that contrasts with the complexities and challenges of modern life.

The concept of Arcady finds its origins in Greek mythology, where it was associated with the god Pan and the nymphs known as the "Arcadian nymphs." Arcadia was a mountainous region in the heart of the Peloponnese, known for its rustic charm and natural beauty. In the myths, it was described as a place where shepherds lived in harmony with their flocks, where the gentle sounds of flutes and lyres filled the air, and where the pastoral lifestyle was idealized. It was, in essence, a vision of an earthly paradise, untouched by the cares and conflicts of the wider world.

Throughout history, the idea of Arcady has resonated with poets, writers, and artists, serving as a potent symbol of an unspoiled and uncorrupted natural world. In the Renaissance, the notion of Arcady experienced a resurgence, as artists and thinkers sought to recapture the simplicity and purity of classical antiquity. Painters like Nicolas Poussin and Claude Lorrain depicted idealized landscapes reminiscent of the Arcadian myth, where shepherds and nymphs roamed in peaceful harmony with nature.

In literature, Arcady has been a recurring theme in pastoral poetry, where it represents a yearning for a simpler, more authentic way of life. The English poet Philip Sidney's "Arcadia" and the pastoral poetry of John Milton and Edmund Spenser all drew upon the idea of Arcady as a symbol of an unspoiled natural world. These works often portrayed shepherds and shepherdesses as emblematic figures of virtue and simplicity, living in a timeless landscape of meadows and groves.

In the 18th century, the Enlightenment brought with it a fascination with Arcady as a contrast to the artificiality and excesses of society. Jean-Jacques Rousseau's writings, particularly his work "Emile, or On Education," emphasized the importance of returning to a more natural and unspoiled way of life, much like the pastoral existence associated with Arcady. Rousseau's philosophy had a profound impact on the Romantic movement, which celebrated nature and the untamed spirit of the individual.

In the visual arts, the Romantic era gave rise to a renewed interest in landscapes that evoked the spirit of Arcady. Painters like Caspar David Friedrich and John Constable captured the sublime beauty of the natural world, often portraying it as a sanctuary of peace and reflection. These artists sought to transport viewers to a realm of pure and unspoiled nature, a place where one could escape the hustle and bustle of industrialized society.

As the world transitioned into the 19th and 20th centuries, the allure of Arcady persisted, albeit in different forms. In literature, authors like F. Scott Fitzgerald explored the idea of an idealized past in works such as "The Great Gatsby," where the past is imagined as a kind of Arcadian paradise. Meanwhile, in the realm of urban planning and architecture, movements like the Garden City and the City Beautiful sought to bring elements of Arcady into the heart of cities, creating green spaces and park-like settings amidst the concrete and steel.

In the 21st century, the concept of Arcady continues to hold a special place in our collective imagination. In an era marked by environmental concerns and a longing for connection to the natural world, the idea of an earthly paradise remains relevant. Whether through literature, art, or our own personal aspirations, Arcady reminds us of the enduring human desire for simplicity, beauty, and harmony with the natural world. It is a timeless vision that continues to inspire and captivate us, offering a glimpse of an idyllic realm where the human spirit can find solace and renewal.

1 note

·

View note

Quote

Je l'aimais. Elle était bête, égoïste et méchante, mais si on n'aimait que les gens qui le méritent, la vie serait une distribution de prix très ennuyeuse.

Emmanuelle Bayamack-Tam, Arcadie.

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Thou still unravish'd bride of quietness/Though foster-child ot silence and slow time/Slyvan historian, who canst thus express/A flowery tale more sweetly than our rhyme:/What leaf-fring'd legend haunts about thy shape/ Of deities or mortals, or of both/ In Tempe or the dales of Arcady?/ What men or gods are these? What maidens loth?/ What mad pursuit? What struggle to escape?/ What pipes and timbrels? What wild ecstasy?" are such raw lines, you'd think they were the first stanza of "Ode to a Grecian Urn" by John Keats written in 1819, compiled as part of the Norton Anthology of English Literature, fifth edition, page 822, but actually I just made them up for a tumblr shitpost!

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Arcadia

Enceladus was one of the Gigantes, the Giants, in Greek mythology, son of Gaea and Uranus. All the Giants were born when Cronus, son of Uranus, castrated his father and the blood fell onto the earth (Gaea).

During the Gigantomachy, the great battle between the Giants and the Olympian gods, Enceladus was the primary adversary of goddess Athena, who threw the island of Sicily against the fleeing Giant and buried him under it. Another source, however, mentions that it was Zeus that hurled a thunderbolt against Enceladus and killed him. Many sources claim that Enceladus was buried under Mount Etna, although others thought it was the monster Typhon or Briareus, one of the Hekatonheires, that was buried there. In any case, Enceladus was considered to be the main cause of earthquakes and volcanic eruptions, and when Mount Etna erupted, it was considered to be Enceladus' breath.

#arcadi#greekmonsters#greekgoddess#greekgod#greekhistory#greekmythology#history#literature#art#picturesque#beauty#dream#beautiful#colorful#colour#picoftheday

0 notes

Video

Partituira - Ligeti - {Excerpts} from Abstract Birds on Vimeo.

Partitura-Ligeti is a collaboration between Abstract Birds + Quayola in the form of a live audiovisual

concert and installation based on Ligeti’s sonata for viola solo, performed by Odile Auboin of

Ensemble intercontemporain, Paris.

Inspired by the studies of artists such as Kandinsky, Paul Klee, Oskar Fischinger and Norman McLaren,

Partitura-Ligeti is inherently connected to music, generating and defining its own coherent visual language .

Through the use of bespoke software, the sound of the viola is analysed and transformed into dynamic graphic scores.

The six Ligeti pieces materialise into linear structures, translating the music and its complexities into abstract

geometries and forms.

Ligeti had a far reaching influential palate from Renaissance to African music, literature, painting, architecture,

science and mathematics, especially the fractal geometry of Benoît Mandelbrot and the writings of Douglas Hofstadter.

The Sonata for Viola Solo, has been described as “perhaps the greatest paean yet written to a single string,

in this case, the viola’s lowest string, “C” its most sensual asset.

Commissioned by Arcadi for Nemo Festival, in collaboration with Ensemble Intercontemporain.

-----

Abstract Birds / Quayola - Artists

Odile Auboin - Musician

Keri Elmsly - Producer

Adam Stark - Sound Analysis

Commissioned by Arcadi and Nemo Festival

In collaboration with Ensemble Intercontemporain

Music by György Ligeti

Developed in VVVV

with additional dx11 support from Julien Vuillet and Matt Swoboda

0 notes

Text

Revista ”Lumina literară și artistică” a împlinit recent patru ani de la prima sa apariție (aprilie 2014). Inițiată și coordonată de Daniela Șontică, publicația apare ca supliment lunar al ”Ziarului Lumina” și se difuzează împreună cu ”Lumina de Duminică”, editate de Centrul de Presă Basilica al Patriarhiei Române. Structura sa a fost definită cu claritate încă de la primul număr, revista devenind în scurt timp cunoscută și apreciată pentru tematica sa, nivelul literar al textelor publicate și acuratețea actului jurnalistic. ”Lumina literară și artistică” cuprinde un interviu cu un scriitor sau artist plastic, un grupaj de poezie, cronici de carte, de teatru, de film, de artă plastică; eseuri pe teme culturale; fragmente de proză. Între personalitățile intervievate până acum: Ana Blandiana, Alex Ștefănescu, Liliana Ursu, Paul Aretzu, Ștefan Mitroi, Octavian Soviany, Monica Pillat, Cassian Maria Spiridon, Theodor Damian, Dumitru Ichim, George Arion, Arcadie Suceveanu, Sever Negrescu, Adrian Lesenciuc, Adrian Munteanu, Florin Caragiu, Robert Șerban, Radmila Popovici, Vasile Baghiu, Tudor Nedelcea, Nicolae Băciuț, Adrian Alui Gheorghe, Daniel Corbu, Emanuela Ilie ș.a.

Poezia aduce în prim-plan mai ales creația de inspirație religioasă.

Să răsfoim paginile câtorva dintre numerele apărute în acești patru ani.

”Postmodernitatea e un corp parazit crescut pe trunchiul modernității, care se alimentează din modernitatea muribundă. Depășirea modernității înseamnă situarea în afara ei, în orizontul unei alte paradigme. Postmodernitatea simplifică, fragmentează, lăsând iluzia creației infinite. Dacă vreți, postmodernitatea e timpul în care cunoașterea nu se mai bazează pe Dumnezeu și pe știință, ci doar pe omul suspendat, reflectat în oglinzi paralele. Literatura postmodernității nu e profundă, ci fragmentată. Evident, e necesară o bună cunoaștere a literaturii modernității pentru a identifica fragmentele izolate, dizolvate sau nu, în masa păstoasă a postmodernității.

Marea literatură nu se împarte pe sine în vârste sau generații, ci împarte timpul, îl coagulează în jurul unor nuclee dense ale propriei expuneri de sine. De aceea, nu tot ceea ce se produce azi e literatură postmodernă. În vremuri postmoderne, marii scriitori produc literatură care excede modernitatea, fără a exista cumva posibilitatea asocierii cu postmodernitatea parazită (a se vedea cazul lui Evgheni Vodolazkin, de pildă).

E simplu să ții pasul, în linii mari, cu literatura actuală. Această literatură, fragmentată, cotidianistă și biografistă, a devenit, întrucâtva, un model în cursurile de Creative writing, o manieră. Adică mai devreme sau mai târziu, ea va sucomba ca proiect.” – Adrian Lesenciuc, ”În afara crezului suntem frunze bătute de vânt”, interviu realizat de Daniela Șontică, septembrie 2017.

” În absenţa transcendentului poţi fi doar un bun meşteşugar sau, într-un caz fericit, poţi să te laşi plămădit de transcendent fără să ştii. Totul e să ai, chiar fără a conştientiza, sensibilitatea de a te lăsa lucrat de transcendent. Să te laşi lucrat de pictură. Pictura e ceva viu care te face pictor.” – Mihai Sârbulescu, ”În absenţa transcendentului poţi fi doar un bun meşteşugar”, interviu realizat de Marina Roman, aprilie 2017.

”Eu cred că interesul pentru poezia religioasă rămâne mereu în altarul unei culturi, al unei literaturi. Poezia religioasă nu-şi trăieşte viaţa pe maidanele culturii, respiră mereu aerul pur al albastrului nedesluşit. Trebuie să-l invoc pe Ioan Alexandru, fiindcă el a definit cel mai bine locul, rolul, viitorul poeziei: «Singurii poeţi care au rămas sunt poeţii creştini, pentru că au obiect! Poezia modernă nu mai are obiect. Nemaivestind Învierea lui Hristos, ce să mai vesteşti, ce să mai spui?» Nu e o sentinţă, e o convingere care vine din credinţă nestrămutată. Poezia religioasă are şi adepţi înfocaţi şi detractori înverşunaţi, demolatori nu doar de credinţă, ci şi de cuvânt. E adevărat, poezia religioasă îşi are şi ea păcatele ei, iar şansa ei e ca balansul dintre religia poeziei şi poezia religiei. Poezia religioasă rămâne dacă e şi poezie, şi credinţă în ea, adică dacă reuşeşte să nu cadă în capcana simplei versificări pe teme religioase. Câtă credinţă atâta literatură, câtă literatură atâta credinţă, am murmurat adeseori.” – Nicolae Băciuț, ”Fără Dumnezeu nu e poezie, cuvântul e bolboroseală”, interviu realizat de Maria-Daniela Pănăzan, martie 2017.

”Viitorul literaturii va însemna întoarcerea ei spre câteva noțiuni aflate astăzi în surprinzătoare scădere de apetit și considerație. Printre ele se află termenii emoție, armonie, trăire, vibrație, talent. Despre ultimul, unul dintre criticii noștri cu reputație spunea că a devenit anacronic, poezia fiind, în esență, apetitul spiritelor cerebrale, ale celor cu înclinație spre descifrarea meandrelor sociale contemporane, iar pentru aceasta nu-ți trebuie dăruiri speciale, ci «calitatea» de a prezenta, «cu sinceritate», relația dintre om și mediul care-l construiește. Pentru mine, ca observator al relației autor-cititor, este clar că această poezie plată, de notație a derizoriului, nu interesează decât pe cineva care are aceleași considerații marginale despre rosturile poeziei, de suficiență față de frumos în sine. Poetul trebuie să redevină cel care scrie pentru ceilalți și nu pentru sine, iar când va face acest lucru, când se va gândi ce îi este necesar celuilalt, ce-l poate mișca și influența, ce îi produce catharsisul, revoluția spiritului, atunci va începe să aibă alte energii creatoare, altă manieră de a modela lucrurile, de a le așeza în echilibru interior.” – Adrian Munteanu, „Legătura cu cerul este cea mai puternică și îți modelează ființa”, interviu realizat de Daniela Șontică, ianuarie 2017.

Fotografii din ”Lumina literară și artistică”

De-a lungul anilor, revista a publicat articole demne de interes dedicate lui Rabindranath Tagore (”90 de ani de la vizita lui Rabindranath Tagore în România”de Francisc-Mihai Lorinczi, noiembrie 2016), Vasile Voiculescu (”Ultimele luni din viața lui Vasile Voiculescu”, restituire documentară datorată istoricului literar Alex. Oproescu, aprilie 2016), Marin Sorescu (”Marin Sorescu sau vocația identității românești” de Tudor Nedelcea, martie 2016), Vasile Andru (”Vasile Andru, fuga în atemporal” de Geo Vasile, noiembrie 2016), Ana Blandiana (”Un roman al realităţii româneşti”, cronică de Paul Aretzu la ”Fals tratat de manipulare”, august 2017), Radu Cârneci, Gheorghe Istrate, Edgar Papu, traduceri de Octavian Soviany din Paul Verlaine (din volumul ”Înțelepciune”, ianuarie 2017) și multe altele.

O parte dintre scriitorii publicați în supliment au fost invitați la cele trei ediții ale Colocviului de literatură creștină organizat de ”Ziarul Lumina”, excelentă inițiativă culturală. Temele abordate au fost: Literatura religioasă de ieri și de azi (2015); Actualitatea lui George Coșbuc, la 150 de ani de la nașterea poetului (2016) și Poezia închisorilor (2017).

Nr. 6 (51), iunie 2018, al revistei va apărea duminică, 24 iunie 2018. Din sumar: interviu cu Paula Romanescu realizat de Daniela Șontică, poeme de Florin Caragiu, articole de Tudor Călin-Zarojanu (”Cum aniversăm centenarul?”), Laurențiu-Ciprian Tudor (”Țara mea de dor”), Paul Aretzu (”Mântuire prin cuvânt”).

Vezi: arhiva ”Lumina literară și artistică”

Arhiva rubricii Revista revistelor culturale

”«Lumina literară și artistică» după 50 de numere” de Costin Tuchilă Revista ”Lumina literară și artistică” a împlinit recent patru ani de la prima sa apariție (aprilie 2014).

0 notes

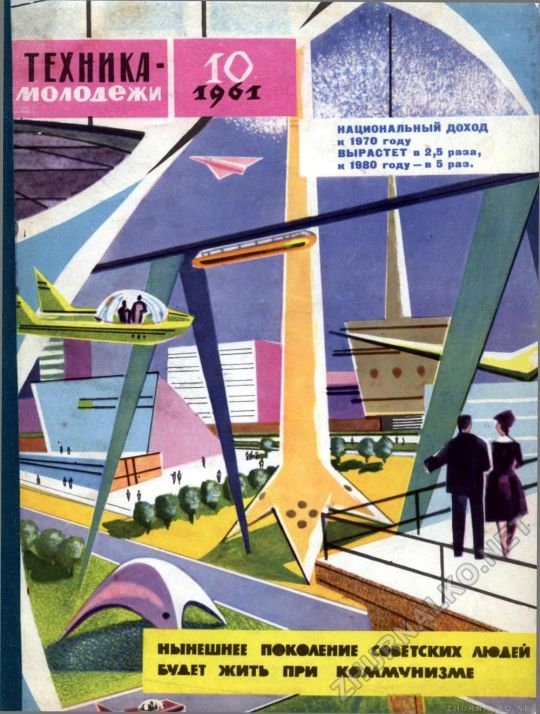

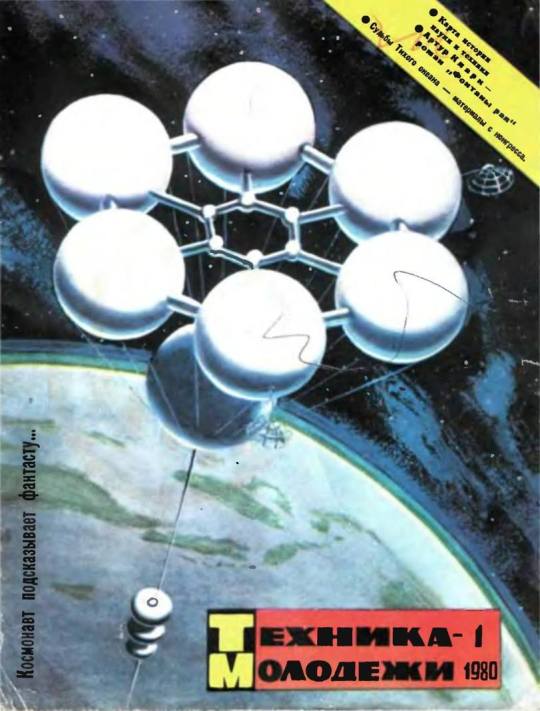

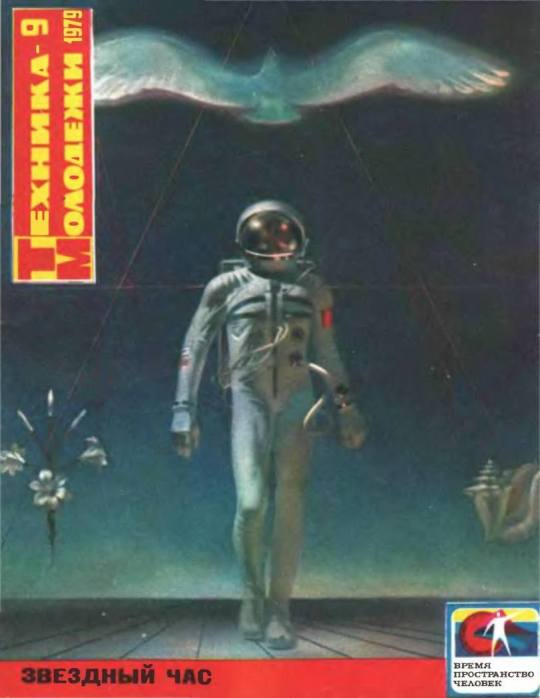

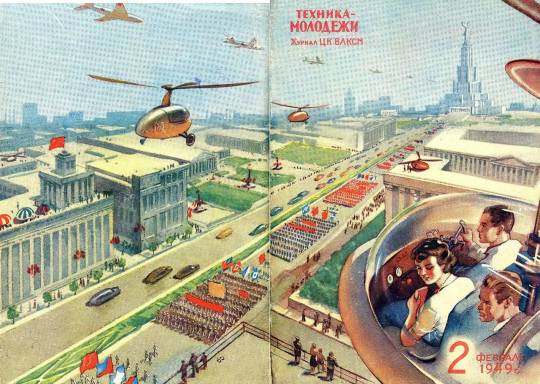

Photo

Tekhnika Molodezhi (1933-2012) magazine

TEKHNIKA MOLODEZHI ("Technology for the Youth") is a Russian journal of science and popular literature, published monthly since 1933, whose central theme is the history, present and future of the technological civilization of humanity. The founding of the journal was linked to the urgent need for the formation of high quality engineering personnel, with the need to awaken the interest of young people in the world of science and technology.

A feature of "Tekhnika Molodezhi" was the popularization of fantastic painting, which contributed greatly to the development of this art in the former Soviet Union. Around the magazine there was a society of unusual illustrators, whose details were reflected in the world of technology, images of fiction and scientific ideas about the future. Illustrations by Artseulov Konstantinovich, Alexander Pobedinsky, Robert Avotin, Georgy Pokrovsky, Andrey Sokolov, Yury Makarov and others, became the magazine's brilliant business cards, recognized as a classic of the genre.

The incredible success of the magazine was attributed not only to the Soviet people's love for engineering and sci-fi stories, but also thanks to the efforts of its editor-in-chief, Vasily Zakharchenko. "Tekhnika Molodezhi" in 1957 was the first to publish Ivan Efremov's "Andromeda Nebula" (the novel was translated into dozens of languages and greatly influenced the worldwide development of science fiction). The magazine's pages were also the launching pad for the novels of the Arcady and Boris Strugatsky brothers, Vladimir Savchenko, Paul Amnuél, Genrikh Altov, Sergey Zhemaitis, Igor Rosokhovatsky, Sever Gansovsky and other Soviet scifi authors. Since 1950, the journal has opened the possibility for readers to get to know the works of foreign authors such as Stanislaw Lem, Edmond Hamilton, Ray Bradbury , Arthur C. Clarke , Isaac Asimov, Robert Sheckley, Paul Anderson and Ursula K. Le Guin.

0 notes

Quote

A quoi bon rêver, je vous le demande, si les rêves doivent être le décalque d'une vie sans intérêt ?

Emmanuelle Bayamack-Tam, Arcadie.

#emmanuelle bayamack-tam#arcadie#literature#french quote#dreams#life#life quote#from books with love

13 notes

·

View notes

Quote

L'amour est faible, facilement terrassé, aussi prompt à s'éteindre qu'à naître. La haine, en revanche, prospère d'un rien et ne meurt jamais. Elle est comme les blattes ou les méduses : coupez-lui la lumière, elle s'en fout ; privez-la d'oxygène, elle siphonnera celui des autres ; tronçonnez-la, et cent autres haines naîtront d'un seul de ses morceaux.

Emmanuelle Bayamack-Tam, Arcadie.

#emmanuelle bayamack-tam#arcadie#literature#french quote#love#love quote#hate#hatred#from books with love

12 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Je suis ce que tu ne t'autoriseras jamais à être : une fille aux muscles d'acier, un garçon qui n'a pas peur de sa fragilité, une chimère dotée d'ovaires et de testicules d'opérette, une entité inassignable, un esprit libre, un être humain intact.

Emmanuelle Bayamack-Tam, Arcadie.

#emmanuelle bayamack-tam#arcadie#literature#french quote#lgbt#intersex#people#girl#boys#from books with love

19 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Meat is murder, mais soixante-dix Syriens peuvent bien s'entasser dans un camion frigorifique et y trouver la mort, je ne sais pas quel crime et quelle carcasse les scandaliseront le plus.

Emmanuelle Bayamack-Tam, Arcadie.

#emmanuelle bayamack-tam#arcadie#literature#french quote#white priveledge#immigrants#vegan#from books with love

7 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Ma lettre au monde tient en quelques mots, que mes frères humains n'auront aucun mal à traduire, quoi qu'il soit advenu de la langue dans l'intervalle qui nous sépare de son exhumation : l'amour existe.

Emmanuelle Bayamack-Tam, Arcadie.

#emmanuelle bayamack-tam#arcadie#literature#french quote#love#love quote#what makes us human#from books with love

5 notes

·

View notes