Text

On my Greatest Accomplishments

Over the course of my rule, I was able to accomplish many things. Here is a top 5 list of my greatest accomplishments for the Russian Empire (according to me).

1. Longest ruling female Empress

My reign lasted for a period of 34 years. The period of my rule has been referred to as the Catherinian Era and is often considered the Golden Age of the Russian Empire. To this day, I am still one of Russia’s most renown rulers.

2. Border expansion and war with the Turks

During my reign, Russia’s border was extended by some 200,000 square miles, absorbing New Russia, Crimea, Northern Caucasus, Right-bank Ukraine, Belarus, Lithuania, and Courland at the expense, mainly, of two powers—the Ottoman Empire and the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth.

3. The Hermitage

If you haven’t already, read my blog post on it.

4. Educational reforms

On 5 August 1786, the Russian Statute of National Education was put into effect. This established a two-tier network of high schools and primary schools which were free of charge, co-educational and open to all of the free classes (not serfs). It also regulated, in detail, the subjects to be taught at every age and the method of teaching. In addition to this, teachers were provided with the “Guide to Teachers” which dealt with teaching methods, the subjects taught, etc. Although the educational program was not entirely successful in reforming education, still around 62,000 pupils were being educated in some 549 state institutions near the end of my reign.

5. Age of Enlightenment

I enthusiastically supported the ideals of the Age of Enlightenment, a movement which dominated intellectual and philosophical thought in Europe during the 18th century. I corresponded with several leading philosophers of the time including Voltaire; and wrote comedies, fiction and memoirs. I sponsored many cultural projects; and played a key role in fostering the arts, sciences and education in Russia.

0 notes

Text

On Serfdom

Many in the past have accused me of not thinking about the serfs in Russia. This simply isn’t true. Serfdom is something that greatly troubles me as a ruler. The Europeans were granting their serfs freedom and land and property, and I was not sure Russia was ready for it.

From 1754 to 1762, I owned 500,000 serfs. A further 2.8 million belonged to the Russian state. At the time of my reign, the landowning noble class owned the serfs, who were bound to the land they tilled. Children of serfs were born into serfdom and worked the same land their parents had. The serfs had very limited rights, but they were not exactly slaves. While the state did not technically allow them to own possessions, some serfs were able to accumulate enough wealth to pay for their freedom.

I did initiate some changes to serfdom, although there was likely more I could have done. If a noble did not live up to his side of the deal, then the serfs could file complaints against him by following the proper channels of law. They were given this new right, but in exchange they could no longer appeal directly to myself or the next ruler. I largely did this because I did not want to be bothered by the peasantry, but also did not want to give them reason to revolt, either. In this act, though, I gave the serfs a legitimate bureaucratic status they had lacked before. Some serfs were able to use their new status to their advantage. For example, serfs could apply to be freed if they were under illegal ownership, and non-nobles were not allowed to own serfs. Some serfs did apply for freedom and were, surprisingly, successful. In addition, some governors listened to the complaints of serfs and punished nobles, but this was by no means all-inclusive.

A landowner could punish his serfs at his discretion, and my rule gained the ability to sentence his serfs to hard labour in Siberia, a punishment normally reserved for convicted criminals. The only thing a noble could not do to his serfs was to kill them.

Although I did not want to communicate directly with the serfs, I also created some measures to improve their conditions as a class and reduce the size of the institution of serfdom. For example, I limited the number of new serfs and eliminated many ways for people to become serfs, culminating in the manifesto of 17 March 1775, which prohibited a serf who had once been freed from becoming a serf again.

As horrible as it may seem, I believed that too much time would elapse before the serfs can escape their poverty. I believed that giving them the right to own property would upset the peasants as it would raise serfs to their own status and no one would be happy. In hindsight, there were probably better ways to handle the question of serfdom.

0 notes

Text

On my Personal Relationships

I realize many of you will be disappointed that I did not discuss my personal relationships here. I understand, but please also understand that so much has been documented that I fear no one would believe me if I told the truth either way. Plus, a lady doesn’t kiss and tell.

Rumours, however, have it that I have had upwards of 12 lovers. I often elevated them to high positions for as long as they held her interest, and then pensioned them off with gifts of serfs and large estates. Some have speculated that I even have children with some (namely Potemkin and Orlov).

Grigorii Orlov will likely be the first one people have heard of. By 1759, he and I had become lovers, it’s true. Peter was cold and abrasive, but no one told him about the affair. I saw Orlov as very useful, and he became instrumental in the 28 June 1762 coup d’état against her husband, but I preferred to remain the Dowager Empress of Russia, rather than marrying anyone. I rewarded Grigorii Orlov and his other three brothers with titles, money, swords, and other gifts, but I did not marry Grigory, who proved inept at politics and useless when asked for advice. He received a palace in Saint Petersburg when I became Empress. He died in 1783.

The next notable lover of mine is of course Potemkin. It seems I have a thing for the Grigorii’s of the world. Grigorii Potemkin was involved in the coup d'état of 1762. In 1772, my close friends informed me of Orlov's affairs with other women, and he was promptly dismissed. By the winter of 1773, the Pugachev revolt had started to threaten my rule. My own son Paul had also started gaining support and so both of these trends threatened my hold on the throne. I called Potemkin for help—mostly military—and he became devoted to me. In 1772, I wrote to Potemkin. I had found out about an uprising in the Volga region and had appointed General Aleksandr Bibikov to put down the uprising, but I needed Potemkin's advice on military strategy. Potemkin quickly gained positions and awards. Russian poets wrote about his virtues, the court praised him, foreign ambassadors fought for his favour, and his family moved into the palace. He later became the de facto absolute ruler of New Russia, governing its colonisation. In 1780, the son of Holy Roman Empress Maria Theresa, Emperor Joseph II, was toying with the idea of determining whether or not to enter an alliance with Russia, and asked to meet me. Potemkin had the task of briefing him and travelling with him to Saint Petersburg. Potemkin also convinced me to expand the universities in Russia to increase the number of scientists. Potemkin fell very ill in August 1783 and I worried he would not finish his work developing the south as he had planned. He was instrumental in securing the Crimean region for Russia. Potemkin died at the age of 52 in 1791.

Overall, it seems my personal life has been of much interest for lots of people, so there you go.

0 notes

Text

On Montesquieu, Voltaire, and the Enlightenment

In eighteenth-century Europe absolutism was ubiquitous. But alongside these absolutist monarchs, there were also those who, in their rule, were practitioners of an ‘enlightened despotism’. These monarchs, though ruling with singular authority, embraced the ideals of the Enlightenment. This often meant being proponents of rationality, religious tolerance, private property rights and freedom of speech. Some of the most famous examples of these despots include Napoleon Bonaparte (1769-1821), Frederick II of Prussia (1712-1786), and Maria Theresa of Austria (1717-1780).

From early on in life, I have embraced Renaissance, and later Enlightenment writings. Our shared love for reading Bayle, Montaigne, Montesquieu and Voltaire cemented the relationship I had with my closest friend Catherine Vorontsova. In my mid-twenties, upon reading Montesquieu’s The Spirit of Laws, I was exposed to an analysis of the strengths and weaknesses of despotic rule. I traveled all over Europe as a young woman, and had devoured French Literature and philosophy in various passionate spurts and critical distances.

Another philosophe that proved influential in my formative years was Voltaire. As a contemporary of mine, Voltaire played a part in my life that Montesquieu, who died during my teenage years, could not. I read Voltaire’s Essay on the Manners and Spirit of Nations during my youth and was greatly enamoured by the wit and humour he brought to his writing. Voltaire argued that reason, not religion, should govern the world and that certain human beings must act as representatives of reason on earth. Thus, he concluded that a despotic government may actually be the best sort of government if it remained reasonable. Voltaire argued that in order for a despotic government to be reasonable it had to be enlightened; and if it were enlightened, then it could be both efficient and benevolent.

My relationship with Voltaire was only through handwritten letters. I never met him in person and he never embarked on a visit to Russia. Many have accused me of not writing the letters myself, but I assure you, they were all mine. He called me La Femme Politique. We exchanged hundreds of letters throughout his lifetime, discussing all sorts of topics. He often expressed interest in my conquests, particularly when discussing the Turks. He seemed eager for details of my victories, his lust for war and for the defeat of the Turk, with his expressed hatred of war and of oppression of the weak by the strong.

Our relationship was one of mutual benefit; he complimented me, I complimented him; he had a ruling empress put his philosophy into practice and I could claim to be in cahoots with one of the great thinkers of the age. However, I was never comfortable enough to allow her country to be personally exposed to Voltaire and his ‘analytical eye’.

I set out my political philosophy in the Nakaz (Instruction). The Russian legal code at the time was over a century old. Despite Peter the Great’s westernizing influence on Russia a half-century before, he had not set down a new legal code within his lifetime. I wanted to rewrite Russian law to raise the levels of government administration, of justice, and of tolerance within her empire. I spent two to three hours a day over the course of two years compiling her Nakaz, and my personal Enlightenment influences were in full evidence: 294 out of the 526 articles in the Nakaz were directly copied from Montesquieu and applied to Russia. For the benefit of my Empire I pillaged President Montesquieu, without naming him in the text. I hope that if he had seen me at work, he would have forgiven this literary theft if only for the good of 20 million people which it may bring about. He loved the humanity too much to be offended; his book was my breviary.

The Instruction is composed of a total of 22 chapters, 655 clauses, an introduction and a conclusion. The first three chapters discuss the current state of the Russian Empire. Chapters 4-10 discuss the existing code of laws as well as Catherine’s opinion of them. The rest of the chapters excluding the last two discuss the people of Russia as a whole. Chapters 21 and 22, the supplementary chapters, come after the conclusion and analyze the organization of the police and the state’s management of money, respectively.

Russia is a European power, and that the nation owes this to the reforms of Peter the Great. I argue that an absolute monarchy is necessary to rule over such a vast realm. It it is better to obey the Laws under the direction of one Master, than to be subject to the Wills of many. My final argument for autocracy is that an absolute government does not deprive people of liberty, but directs them so that they can contribute to the overall society to make it better.

0 notes

Text

On Educational Reforms

I have always held western European philosophies and culture close to her heart, and I have always wanted to surround myself with like-minded people within Russia. I believe a new kind of person could be created by inculcating Russian children with European education.

I believe education can change the hearts and minds of the Russian people and turn them away from backwardness. This means developing individuals both intellectually and morally, providing them knowledge and skills, and fostering a sense of civic responsibility.

I have appointed Ivan Betskoy as my advisor on educational matters. Through him, I have collected information from Russia and other countries about educational institutions. I have also established a commission composed of T.N. Teplov, T. von Klingstedt, F.G. Dilthey, and the historian G. Muller. I have been consulting British education pioneers, particularly the Rev. Daniel Dumaresq and Dr John Brown.

In 1764, I even sent for Dumaresq to come to Russia and then appointed him to the educational commission. The commission studied the reform projects previously installed by I.I. Shuvalov under Elizabeth and under Peter III. They submitted recommendations for the establishment of a general system of education for all Russian orthodox subjects from the age of 5 to 18, excluding serfs. However, no action was taken on any recommendations put forth by the commission due to the calling of the Legislative Commission.

In July 1765, Dumaresq wrote to Dr. John Brown about the commission's problems and received a long reply containing very general and sweeping suggestions for education and social reforms in Russia. Dr. Brown argued, in a democratic country, education ought to be under the state's control and based on an education code. He also placed great emphasis on the proper and effectual education of the female sex.

Two years prior, I had commissioned Ivan Betskoy to draw up the General Programme for the Education of Young People of Both Sexes. This work emphasized the fostering of the creation of a 'new kind of people' raised in isolation from the damaging influence of a backward Russian environment. The Establishment of the Moscow Foundling Home, or the Moscow Orphanage was the first attempt at achieving that goal. It was charged with admitting destitute and extramarital children to educate them in any way the state deemed fit. Since the Moscow Foundling Home was not established as a state-funded institution, it represented an opportunity to experiment with new educational theories. However, the Moscow Foundling Home was unsuccessful, mainly due to extremely high mortality rates, which prevented many of the children from living long enough to develop into the enlightened subjects the state desired.

Not long after the founding, I wrote a manual for the education of young children, drawing from the ideas of John Locke, and founded the famous Smolny Institute in 1764, first of its kind in Russia. At first, the Institute only admitted young girls of the noble elite, but eventually it began to admit girls of the petit-bourgeoisie, as well.

The girls who attended the Smolny Institute, Smolyanki, were often accused of being ignorant of anything that went on in the world outside the walls of the Smolny buildings. Within the walls of the Institute, they were taught impeccable French, musicianship, dancing, and complete awe of the Monarch. At the Institute, enforcement of strict discipline was central to its philosophy. Running and games were forbidden, and the building was kept particularly cold because too much warmth was believed to be harmful to the developing body, as was excess play. Nonetheless, the establishment of the institute was a significant step in making education available for females in Russia.

I continued to investigate educational theory and practice of other countries and continued to make many educational reforms despite the lack of a national school system. The remodelling of the Cadet Corps 1766 initiated many educational reforms. It then began to take children from a very young age and educate them until the age of 21. The curriculum was broadened from the professional military curriculum to include the sciences, philosophy, ethics, history, and international law. This policy in the Cadet Corps influenced the teaching in the Naval Cadet Corps and in the Engineering and Artillery Schools. Unfortunately, no national education system was set up.

0 notes

Text

On War and Expansion

Foreign affairs began to demand my attention once I felt more secure in my reign. During my reign, Russia greatly expanded its borders. We made substantial gains in Poland. Russia's main dispute with Poland was over the treatment of many Orthodox Russians who lived in the eastern part of the country. In a 1772 treaty, I gave parts of Poland to Prussia and Austria, while taking the eastern region myself

Russia's actions in Poland triggered a military conflict with Turkey. Enjoying numerous victories in 1769 and 1770, I showed the world that Russia was a mighty power. I reached a peace treaty with the Ottoman Empire in 1774, bringing new lands into the empire and giving Russia a foothold in the Black Sea.

Even before the peace talks ended, I also had to concern myself with a revolt led by the Cossack Yemelyan Pugachev. The rebel leader claimed that reports of Peter III's death were false and that he was in fact Peter III. Soon tens of thousands were following him, and the uprising was within threatening range of Moscow. Pugachev's defeat required several major expeditions by the imperial forces. A feeling of security returned to the government only after his capture late in 1774.

One of the war's heroes, Gregory Potemkin, became a trusted adviser and lover of mine. Ruling over newly gained territories in southern Russia in my name, he started new towns and cities, and built up the country's navy there. Potemkin also encouraged me to take over the Crimea peninsula in 1783, shoring up Russia's position in the Black Sea.

A few years later, we once again clashed with the Ottoman Empire. This time the fighting would last until 1792.

In the Treaty of Georgievsk, signed in 1783, Russia agreed to protect Georgia against any new invasion and further political aspirations of their Persian suzerains. I was forced to wage a new war against Persia in 1796 after they, under the new king Agha Mohammad Khan, had again invaded Georgia and established rule in 1795 and had expelled the newly established Russian garrisons in the Caucasus.

The ultimate goal, however, was to topple the anti-Russian shah (king), and to replace him with a half-brother, Morteza Qoli Khan, who had defected to Russia and was therefore pro-Russian. Many expected that a 13,000-strong Russian corps would be led by the seasoned general, Ivan Gudovich, but the I followed the advice of Prince Zubov and entrusted the command to his brother Count Valerian Zubov.

The Russian troops set out from Kizlyar in April 1796 and stormed the key fortress of Derbent on 10 May. By mid-June, Zubov's troops overran without any resistance most of the territory of modern-day Azerbaijan, including three principal cities—Baku, Shemakha, and Ganja. By November, they were stationed at the confluence of the Araks and Kura Rivers, poised to attack mainland Iran.

1 note

·

View note

Text

On the Hermitage

Oh where do I begin? This is my pride and join and it warms my heart so that it is still standing intact.

There are many origin stories for the Hermitage. One in particular begins with a myth. One day during the early months of my reign, I accidentally noticed a large Rubens painting depicting the disposition of Christ from the cross. I stood in front of the canvas for a long time admiring it, when it suddenly occurred to me that I should have an art gallery of my own. Soon enough I ordered all the best paintings in the country be gathered from private collections and delivered to the Winter Palace. I also dispatched envoys abroad for the same purpose.

I can tell you, my readers, while this story has some truth to it, it largely paints my motivations for the paintings from an aesthetic reason. In all honestly, I have no real understanding of art.

My first purchase was 225 paintings from the collection of Berlin merchant Johann Gotzkowski. Frederick II has just passed up this collection due to insufficient funds (Seven Years’ War will do that to a man). Following this purchase, I swooped in on numerous other collections, building up my personal collection. I acquired all these collections in their entirety, sparing no canvas. My gain meant a loss for another European power.

Aside from annoying my competitors, it seemed to draw attention from the international community. I had an unquenchable thirst for culture and in some ways, this art collection helped quench that.

I gathered a total of 4000 paintings that came to rival the older and more prestigious museums of Western Europe. My museum in its early days consisted of 38,000 volumes, four rooms filled with books and engravings, 10,000 cut gemstones, nearly 10,000 drawings, and a natural history collection that occupied two large halls. It was quite an achievement.

Time and time again, art has served as a visible sign of cultural enlightenment. European princes patronized art for political reasons - to glorify themselves and their state. I wanted to play with the big boys. The Hermitage was first if all an institution of triumphant display.

Behind the scenes, I delegated the power of aesthetic judgement to several key advisors, Grimm, Prince Dmitry Golitsyn, Ivan Shuvalov, and Senator Aleksandr Stroganov.

While the collection was incredible, so too was the building housing it. Originally Empress Elizabeth Petrovna commissioned the design back in 1754, but had it done in a Baroque style. I must confess that it was not to my liking and I hired Yury Felten to build an extension on the east of the Winter Palace which he completed in 1766. Later it became the Southern Pavilion of the Small Hermitage. In 1767–1769, French architect Jean-Baptiste Vallin de la Mothe built the Northern Pavilion on the Neva embankment. Between 1767 and 1775, the extensions were connected by galleries, where I placed my collections. During my time, the Hermitage was not a public museum and few people were allowed to view its holdings. Mostly it was only open to the court or to visiting foreigners.

The Hermitage buildings served as a home and workplace for nearly a thousand people, including the Imperial family. In addition to this, they also served as an extravagant showplace for all kinds of Russian relics and displays of wealth prior to the art collections. Many events were held in these buildings including masquerades for the nobility, grand receptions and ceremonies for state and government officials. The "Hermitage complex" was a creation of mine that allowed all kinds of festivities to take place in the palace, the theatre and even the museum of the Hermitage. This helped solidify the Hermitage as not only a dwelling place for the Imperial family, but also as an important symbol and memorial to the imperial Russian state.

Today, the palace and the museum are one and the same. In my day, the Winter Palace served as a central part of what was called the Palace Square. The Palace Square served as St. Petersburg's nerve center by linking it to all the city's most important buildings. The presence of the Palace Square was extremely significant to the urban development of St. Petersburg, and while it became less of a nerve center later into the 20th century, its symbolic value was still very much preserved.

Through the art collection, I gained European acknowledgment and acceptance, and portrayed Russia as an enlightened society, something of utmost importance to me. I invested much of her identity in being a patron for the arts. I was particularly fond of the popular deity, Minerva, whose characteristics according to classical tradition are symbolic of military prowess, wisdom, and patronage of the arts.

0 notes

Text

Early Reign 1762–1764

Most of my early days as Empress were spent securing the throne. I was quite insecure as I had a son growing up who would be crowned when he became of age, but he was also quite sickly. Then, there were the rumours that surrounded my ascension to the throne: many speculated I ordered the murder of my husband (which I did not), some speculated on the amount of partners I had, some even questions my loyalty to Russia. On top of this, I was surrounded by those to whom I owed my position on the throne. They risked their lives for me and were deserving of reward. It was a difficult time in my reign.

I had ambitious plans regarding both domestic and foreign affairs. I knew that a number of influential persons considered me a usurper, or someone who seized another's power illegally. They viewed my son, Paul, as the rightful ruler. I took every opportunity to win favour among the nobility and the military.

As for general policy, Russia needed an extended period of peace in order for me to concentrate on domestic (homeland) affairs. I understood that this peace could only be gained through cautious foreign policy. I appointed Count Nikita Panin in charge of foreign affairs. He had once taught my son and I thought him both competent and loyal.

0 notes

Text

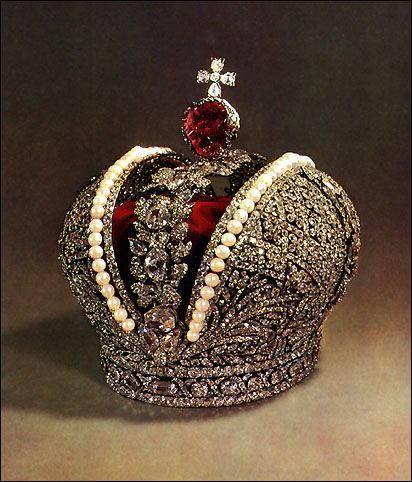

Imperial Crown of Russia

I was crowned at the Assumption Cathedral in Moscow on September 22, 1762. The Imperial Crown of Russia was actually designed to my specifications by Swiss-French court diamond jeweller Jérémie Pauzié. Inspired by the Byzantine Empire design, the crown was constructed of two gold and silver half spheres, representing the eastern and western Roman empires, divided by a foliate garland and fastened with a low hoop. The crown contains 75 pearls and 4,936 Indian diamonds forming laurel and oak leaves, the symbols of power and strength, and is surmounted by a 398.62-carat ruby spinel that previously belonged to the Empress Elizabeth, and a diamond cross. The crown was produced in a record two months and weighed 2.3 kg. It was definitely a heavy crown to carry on my head...

1 note

·

View note

Photo

On the balcony of the Winter Palace welcoming the Guards and the People on the day of the coup

- July 9, 1762

0 notes

Text

On Rising to Power, Part 2

Last we talked, I just got married to Peter III. Now, let’s figure out how I got to be sole Empress of Russia.

When Empress Elizabeth died on December 25, 1761, Peter was proclaimed Emperor Peter III, and I was empress. We moved to the Winter Palace in Saint Petersburg. Within a few short months of being on the throne, Peter had managed to alienate many members within the government, the military and the church. His eccentricities and his support for Frederick II shattered all the alliances I had so carefully built.

The truth is very few liked Peter as an emperor. He was abrasive, eccentric and ill-mannered. He was determined to make sure I was removed. Just weeks before the coup, he publicly humiliated me, by calling me a fool at the dinner table! He threatened me with death, both political and physical. I was told by my advisors that he planned on arresting me and throwing me in a convent for the rest of my life, disinheriting my son Paul, and marrying his fat, ugly mistress. Prince Georg talked him out of acting upon this, but the threat was already there: he would remove me by prison or by poison.

The future of the Russian empire was at stake. I was a much better fit for the crown anyway. And so I took my destiny into my own hands. I already had widespread support from people like Ekaterina Dashkova, Grigorii Orlov, my lover at the time, and his four brothers, and Nikita Panin who supervised my son’s education. All that was left was to find the right time to strike.

Luckily, Peter made the mistake of taking a holiday with his Holstein-born courtiers and relatives to Oranienbaum, leaving me in Saint Petersburg.

On June 28, 1762 I was up at dawn. I was awakened in my tiny palace of Mon Plaisir, built for Peter the Great in his favourite summer residence of Peterhof, some twenty nine kilometres from the new capital. Aleksei Orlov came to me informing me that Captain Passek had been arrested and we needed to move quickly if I wanted to ever ascend to the throne. I followed Orlov to his coach waiting outside and sat tensely and the vehicle hurled away to Saint Petersburg.

We stopped five kilometres outside of Saint Petersburg. Grigorii Orlov had met us and I was ushered into a smaller coach. We travelled to the suburban quarters of the Izmailovskii Guards who repudiated Peter III and swore their allegiances to me. Hurrahs punctured the quiet morning air and many lined up to kiss my hand or the hem of my dress. Several were assisting Father Aleksei, the regiment’s priest, as he held up the cross and administered the new oath of allegiance.

This was meant to be a peaceful, bloodless revolution. Swift and safe. The first half had gone off without a hitch

Toward eight o’clock an excited crowd formed around us, as the carriage moved through the town towards the Semenovskii Guards. The news preceded us, however, and large crowds of Semenovtsy rushed out to greet us. The multiplying crowd diverted us onto Nevskii Prospect, the capital’s central avenue. We were then joined by some of Preobrazhensty, guards from Peter III’s favourite Guards regiment.

Slowly, we moved towards the Church of Our Lady of Kazan. Joined by the Orlov brothers, Count Razumovskii, Prince Volkonskii, Count Bruce, Count Stroganov, and numerous guard officers, I entered the church. The priests greeted us with icons and prayers for my long life. The church bells rang as we continued our march to the Winter Palace.

On the squares before and beside the palace, regiments of regular troops stood guard and quickly swore oats of allegiance read by Veniamin, the archbishop of Saint Petersburg. The same oat was administered to everyone inside the palace, including many high court, military and ecclesiastical officials. My son was also rushed to the Winter Palace by Nikita Panin. That morning my manifesto announced my assumption of the throne. It was justified by claims that Orthodoxy had been endangered, Russia’s military glory sullied and enslaved by the alliance with Prussia, and the Empire’s institutions “completely undermined”.

The rest of the day was spent consolidating our coup. Troops had been assigned to guard every approach to the capital, Prince Georg was arrested and later confined to his house, which the soldiers ruthlessly looted. I left the palace in favour of the old wooden one where Elizabeth died. The question remained, however, what should I do about Peter and his supporters?

Naturally, Peter would attempt to garner support, and of particular worry was Kronstadt, as it was an island-fortress that lay within sight of Oranienbaum. There were naval units, infantry and munition there which he could use to mount an assault on Saint Petersburg. We were unsure if word had reached Kronstadt. In order to ensure my reign was secure, we sent Admiral Talyzin empowering him to do whatever he thought appropriate. On the other hand. we also ordered Rear-Admiral Miloslavskii to administer the oath of allegiance to the naval units in the Gulf of Finland and guard against any seaborne assault. And so it was decided that Peter would be taken to the fortress prison of Schlüsselburg, forty kilometres upstream from the capital.

It seemed though, that Peter had not yet decided on any countermeasures. This reassured me that the capital was in safe hands. Hence, with my reign assured, I accompanied the military on an offensive in Peterhof. I suppose this would have been quite unique for the time. Peter was surely surprised to see me at the helm, a colonel, saver on hand on my white steed. Princess Dashkova also accompanied me in battle in a Guards uniform. It was quite a sight to see.

Our army reached Peterhof by ten a.m. on June 29. In the meantime, the Orlovs had easily occupied both Peterhof and Oranienbaum with bloodshed or much resistance. Peter sent me a letter begging for forgiveness, renouncing the throne and requesting permission to leave for Holstein. General Izmailov hand-delivered the message and even offered to deliver Peter himself once he signed a formal abdication. The document was drafted, Peter signed it immediately and got in the carriage to Peterhof. Peter stepped out of the carriage, surrendered his sword and his ribbon of St. Andrew. He was also forced to surrender his uniform. Peter’s abdication completed the formal processes of the coup.

Unfortunately, on July 6 Peter died at Ropsha. I received the news that very evening that he died of hemorrhoidal colic. His body was placed at the Alexander Nevski Monastery where people could pay their respects.Truth be told, I’m still not sure if that was truly what he died from or if he had tried to escape and was killed in the effort. Some say that the Orlov brothers had a hand in his death. I believe I will never know the truth, but likely it was not of natural causes.

0 notes

Text

On Rising to Power, Part 1

If you read the last blog, you already know the story of my early childhood. It was unimpressive to say the least. But, now, you get to find out how I started my journey to Empress of Russia. This journey a far more interesting one.

When I was fifteen, I went to Russia at the invitation of Empress Elizabeth to meet the heir to the throne, the Grand Duke Peter (1728–1762). I already met Peter III at the age of 10 and he was first in line to become tsar Peter of Holstein-Gottorp.

The decision to marry me off to my second cousin (yes, this was normal at the time, although would likely be frowned upon in the modern day), resulted from some amount of diplomatic management in which Count Lestocq, Peter's aunt (and ruling Russian Empress) Elizabeth and Frederick II of Prussia took part. Lestocq and Frederick wanted to strengthen the friendship between Prussia and Russia to weaken Austria's influence and ruin the Russian chancellor Bestuzhev, on whom Empress Elizabeth relied, and who acted as a known partisan of Russo-Austrian co-operation.

The first time I met Peter, I knew this would not be a desirable marriage for me. I disliked his pale complexion and his fondness for alcohol at such a young age. Peter was still a child and played with toy soldiers. While living together, I stayed at one end of the castle, and Peter at the other.

The diplomatic intrigue surrounding my marriage failed, largely due to the efforts of my own mother. You see, she loved to gossip and court intrigue. The Empress Elizabeth knew our family all too well: she had intended to marry Princess Johanna's brother Charles Augustus (Karl August von Holstein), who unfortunately died of smallpox in 1727 before the wedding could take place. Although Empress Elizabeth despised my mother, she strangely took a strong liking to me. With that said, I spared no effort to immerse myself in the Russian culture and customs. Upon my arrival in 1744, I put a lot of energy into learning the Russian language. I remember rising at night and walking about the bedroom barefoot, repeating my lessons. I was committed to learning the language as soon as possible, but even though I learned the language, my accent was still strong and discernible.

Unfortunately, doing this led to a severe attack of pneumonia in March of the same year. Perhaps it was due to my mother’s influence, perhaps it was my own ambition, but I made up my mind when I came to Russia to do whatever was necessary, and to profess to believe whatever was required of me, to become qualified to wear the crown.

Upon my arrival to Russia, funny enough, I fell ill with a pleuritis that almost killed me. I credited my survival to frequent bloodletting; in a single day, I had four phlebotomies (the surgical opening or puncture of a vein in order to withdraw blood or introduce a fluid, or as part of the procedure of letting blood). My mother was severely opposed to this practice. As the situation got worse and I was on my deathbed, my mother wanted me confessed by a Lutheran priest. Awaking from my delirium, however, I remember saying: "I don't want any Lutheran; I want my orthodox father clergyman."

My conversion to Orthodoxy greatly upset my family. My father, a devout German Lutheran was particularly upset. But despite his objections on 28 June 1744 I was received by the Russian Orthodox Church as a member with my new name Catherine. I was given the patronymic, albeit artificial, Алексеевна, or Alekseyevna, daughter of Aleksey. On the following day, our formal betrothal took place. The long-planned dynastic marriage finally occurred on 21 August 1745 in Saint Petersburg. I had just turned 16; my father was still upset over my conversion and hence, did not travel to Russia for the wedding. The bridegroom, known then as Peter von Holstein-Gottorp, had become Duke of Holstein-Gottorp (located in the north-west of present-day Germany near the border with Denmark) in 1739. We settled in the palace of Oranienbaum, which remained the residence of the "young court" for many years to come.

Then began the rumours. Many speculated that Peter took on a mistress, one Elizabeth Vorontsova. Many accused me of having affairs of my own. I will not comment here on what is true and what is not. I actually became friends with the sister of Elizabeth Vorontsova, Princess Ekaterina Vorontsova-Dashkova. She introduced me to several powerful political groups that opposed my husband. Peter’s temperament became quite unbearable for those who resided in the palace. He would announce trying drills in the morning to male servants, who later joined me in my room to sing and dance until late hours.

I became pregnant with my second child, Anna, in 1759. Sadly, she only survived for four months. Due to various rumours of my promiscuity, Peter believed he was not the child's biological father. I dismissed the accusations, but Peter only said, "Go to the devil!". I spent much time alone in my private boudoir to hide away from Peter's abrasive personality.

I used to say to myself that happiness and misery depend on ourselves. If you feel unhappy, raise yourself above unhappiness, and so act that your happiness may be independent of all eventualities. And that I did.

0 notes

Text

My Childhood

Many of you have asked about what it was like to be me growing up. I must say that it was hardly interesting or out of the ordinary for the royalty of the time. I was born Sophia Augusta Fredericka in the German city of Stettin, Prussia, now Szczecin, Poland. Formally my title was Princess Sophie Friederike Auguste von Anhalt-Zerbst-Dornburg. I am the daughter of Prince Christian August of Anhalt-Zerbst and Princess Johanna Elizabeth of Holstein-Gottorp. My father, Christian August, Prince of Anhalt-Zerbst, belonged to the ruling German family of Anhalt, but held the rank of a Prussian general in his capacity as governor of the city of Stettin.

My parents had been hoping for a son but instead they had me. Little did they know I would go on to be Empress of Russia. Nonetheless, they did not show a great deal of affection towards me. As a child, I was closer to my governess Babette than my own parents or siblings. She was the kind of governess every child should have. Naturally, I was educated in all the traditional subjects one would expect from someone of my social standing: religion, Lutheranism in this case, history, French, German, and music. These were subjects that always interested me and continued to interest me all my life. I embraced the Renaissance, and later Enlightenment writings. I was and am to this day a huge fan of Peter the Great. I believe he laid down the foundations that were needed for Russia to become the empire it is today. His reforms led Russia down a path of modernization and allowed our empire to come closer to Europe than ever before.

Although my title was “Princess”, our family had very little money. My rise to power was largely supported by my mother's wealthy relatives who were both wealthy nobles and had royal relations. Some have said my mother was cold and abusive, but I do not believe that was so. I believe she was the way she was largely because she wanted me to have the crown. My mother also managed to infuriate the Empress Elizabeth, who eventually banned her from the country for spying for King Frederick of Prussia.

Overall, as you can see, my childhood was rather simple. Life only became more and more complicated as I got older.

0 notes

Text

The only cats we keep in the palace 😻

0 notes

Text

You philosophers are lucky men. You write on paper and paper is patient. Unfortunate Empress that I am, I write on the susceptible skins of living beings.

Catherine the Great

0 notes