Text

Eclipse pics from where I am (the smudges on my window made those little suns)

879 notes

·

View notes

Photo

This is the lucky clover cat. reblog this in 30 seconds & he will bring u good luck and fortune.

1M notes

·

View notes

Note

Have you ever cried or been significantly upset at the death of a celebrity?

Yes (which one?), because I cared about them or their work

Yes, for practical reasons (ex. it was a politician with good political views)

Yes, but not because I cared about them (ex. their cause of death was a trigger for you)

No, but I would if certain famous people were to die

No, and I wouldn't even if a celebrity I liked died

No, because there are no celebrities I like/care about

Other (put in tags)

8K notes

·

View notes

Text

$50,000 immediately dropped into my bank account wouldn't improve EVERYTHING but boy it sure would be a grand, sexy little start to a good, happy life path, don't you think

673K notes

·

View notes

Text

Every now and then I get asked about ships, and I usually avoid the question both because I think it's obvious what will win and because "ship wars" just aren't fun. But, fine. Just this once, in honor of Valentine's Day, ~let the ship wars rage~. Hopefully no one sails too far west and triggers the sinking of Númenor.

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

REBLOG if you have amazing, talented WRITER friends.

Because I certainly do, and I love every single one of them and their work.

192K notes

·

View notes

Text

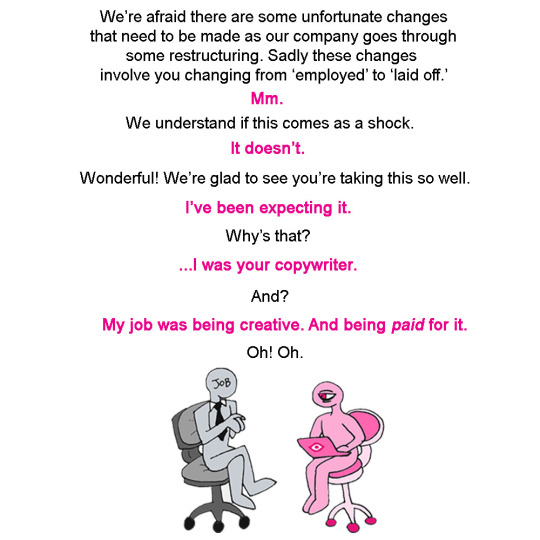

Guess who’s unemployed?

It was only a matter of time considering the job market for any sucker who has ‘writer’ or ‘artist’ or ‘Hey You Can Probably Hit a Button and Make a Bot Spit Up Something Instead of Paying Someone for This!’ in their title. So, you know. Saw it coming.

I have a little saved up to allow myself a brain-breather and take a sabbatical for this month before throwing myself into Job Hunt Hell. But in the meantime, I’ll go ahead and drop my Ko-Fi info here if you want to drop in a buck or a commission request.

Minor silver lining: No interruptions or waiting for the weekend to tackle the last of The Vampyres’ self-publishing pains. So it may be churned out sooner than expected. I’ll keep you updated.

618 notes

·

View notes

Text

If you see this you’re legally obligated to reblog and tag with the book you’re currently reading

232K notes

·

View notes

Text

Saw a post like this with negative outlook so I asked for it to be fixed

77K notes

·

View notes

Text

A reminder and a preface all about ravens

Master Humphrey’s Clock is ticking…

This is merely a reminder that Dickens Daily will be returning to your inboxes next month with our second novel, Barnaby Rudge. Originally serialised in 1841, instalments will be sent out from 13th February 2024 until the end of November. As with Great Expectations, chapters will be sent out either once or twice per week depending on what was included in the relevant 1841 instalment of Master Humphrey’s Clock for that week.

There is a slight complication this time, due to 2024 being a leap year when 1841 was not. This means that the weekdays for the emails will change after a couple of weeks to keep in line with the correct dates, but after that they will remain steady. Thus, Chapters 1-5 will be sent out on Tuesdays and Fridays, then from Chapter 6 (6th March) onwards they will be sent out on Wednesdays and Saturdays.

If you haven't signed up yet, you can do so at dickensdaily.substack.com!

Get excited!

To whet your appetite, we’ve included below the preface Dickens wrote for the 1849 cheap edition of Barnaby Rudge. This did not appear when originally serialised, so this is just a little extra! Get ready to learn all about ravens…

Dickens’ raven Grip, taxidermied

Preface to Barnaby Rudge by Charles Dickens

The late Mr Waterton having, some time ago, expressed his opinion that ravens are gradually becoming extinct in England, I offered the few following words about my experience of these birds.

The raven in this story is a compound of two great originals, of whom I was, at different times, the proud possessor. The first was in the bloom of his youth, when he was discovered in a modest retirement in London, by a friend of mine, and given to me. He had from the first, as Sir Hugh Evans says of Anne Page, ‘good gifts’, which he improved by study and attention in a most exemplary manner. He slept in a stable—generally on horseback—and so terrified a Newfoundland dog by his preternatural sagacity, that he has been known, by the mere superiority of his genius, to walk off unmolested with the dog’s dinner, from before his face. He was rapidly rising in acquirements and virtues, when, in an evil hour, his stable was newly painted. He observed the workmen closely, saw that they were careful of the paint, and immediately burned to possess it. On their going to dinner, he ate up all they had left behind, consisting of a pound or two of white lead; and this youthful indiscretion terminated in death.

While I was yet inconsolable for his loss, another friend of mine in Yorkshire discovered an older and more gifted raven at a village public-house, which he prevailed upon the landlord to part with for a consideration, and sent up to me. The first act of this Sage, was, to administer to the effects of his predecessor, by disinterring all the cheese and halfpence he had buried in the garden—a work of immense labour and research, to which he devoted all the energies of his mind. When he had achieved this task, he applied himself to the acquisition of stable language, in which he soon became such an adept, that he would perch outside my window and drive imaginary horses with great skill, all day. Perhaps even I never saw him at his best, for his former master sent his duty with him, ‘and if I wished the bird to come out very strong, would I be so good as to show him a drunken man’—which I never did, having (unfortunately) none but sober people at hand.

But I could hardly have respected him more, whatever the stimulating influences of this sight might have been. He had not the least respect, I am sorry to say, for me in return, or for anybody but the cook; to whom he was attached—but only, I fear, as a Policeman might have been. Once, I met him unexpectedly, about half-a-mile from my house, walking down the middle of a public street, attended by a pretty large crowd, and spontaneously exhibiting the whole of his accomplishments. His gravity under those trying circumstances, I can never forget, nor the extraordinary gallantry with which, refusing to be brought home, he defended himself behind a pump, until overpowered by numbers. It may have been that he was too bright a genius to live long, or it may have been that he took some pernicious substance into his bill, and thence into his maw—which is not improbable, seeing that he new-pointed the greater part of the garden-wall by digging out the mortar, broke countless squares of glass by scraping away the putty all round the frames, and tore up and swallowed, in splinters, the greater part of a wooden staircase of six steps and a landing—but after some three years he too was taken ill, and died before the kitchen fire. He kept his eye to the last upon the meat as it roasted, and suddenly turned over on his back with a sepulchral cry of ‘Cuckoo!’ Since then I have been ravenless.*

Of the story of BARNABY RUDGE itself, I do not think I can say anything here, more to the purpose than the following passages from the original Preface.

‘No account of the Gordon Riots having been to my knowledge introduced into any Work of Fiction, and the subject presenting very extraordinary and remarkable features, I was led to project this Tale.

‘It is unnecessary to say, that those shameful tumults, while they reflect indelible disgrace upon the time in which they occurred, and all who had act or part in them, teach a good lesson. That what we falsely call a religious cry is easily raised by men who have no religion, and who in their daily practice set at nought the commonest principles of right and wrong; that it is begotten of intolerance and persecution; that it is senseless, besotted, inveterate and unmerciful; all History teaches us. But perhaps we do not know it in our hearts too well, to profit by even so humble an example as the ‘No Popery’ riots of Seventeen Hundred and Eighty.

‘However imperfectly those disturbances are set forth in the following pages, they are impartially painted by one who has no sympathy with the Romish Church, though he acknowledges, as most men do, some esteemed friends among the followers of its creed.

‘It may be observed that, in the description of the principal outrages, reference has been had to the best authorities of that time, such as they are; the account given in this Tale, of all the main features of the Riots, is substantially correct.

‘It may be further remarked, that Mr Dennis’s allusions to the flourishing condition of his trade in those days, have their foundation in Truth, and not in the Author’s fancy. Any file of old Newspapers, or odd volume of the Annual Register, will prove this with terrible ease.

‘Even the case of Mary Jones, dwelt upon with so much pleasure by the same character, is no effort of invention. The facts were stated, exactly as they are stated here, in the House of Commons. Whether they afforded as much entertainment to the merry gentlemen assembled there, as some other most affecting circumstances of a similar nature mentioned by Sir Samuel Romilly, is not recorded.’

That the case of Mary Jones may speak the more emphatically for itself, I subjoin it, as related by SIR WILLIAM MEREDITH in a speech in Parliament, ‘on Frequent Executions’, made in 1777.

‘Under this act,’ the Shop-lifting Act, ‘one Mary Jones was executed, whose case I shall just mention; it was at the time when press warrants were issued, on the alarm about Falkland Islands. The woman’s husband was pressed, their goods seized for some debts of his, and she, with two small children, turned into the streets a-begging. It is a circumstance not to be forgotten, that she was very young (under nineteen), and most remarkably handsome. She went to a linen-draper’s shop, took some coarse linen off the counter, and slipped it under her cloak; the shopman saw her, and she laid it down: for this she was hanged. Her defence was (I have the trial in my pocket), “that she had lived in credit, and wanted for nothing, till a press-gang came and stole her husband from her; but since then, she had no bed to lie on; nothing to give her children to eat; and they were almost naked; and perhaps she might have done something wrong, for she hardly knew what she did.” The parish officers testified the truth of this story; but it seems, there had been a good deal of shop-lifting about Ludgate; an example was thought necessary; and this woman was hanged for the comfort and satisfaction of shopkeepers in Ludgate Street. When brought to receive sentence, she behaved in such a frantic manner, as proved her mind to be in a distracted and desponding state; and the child was sucking at her breast when she set out for Tyburn.’

LONDON, March 1849

* This was later updated to the below for the 1858 Library Edition:

After this mournful deprivation, I was, for a long time, ravenless. The kindness of another friend at length provided me with another raven; but he is not a genius. He leads the life of a hermit, in my little orchard, on the summit of SHAKESPEARE’S Gad’s Hill; he has no relish for society; he gives no evidence of ever cultivating his mind; and he has picked up nothing but meat since I have known him – except the faculty of barking like a dog.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

If you could instantly be granted fluency in 5 languages—not taking away your existing language proficiency in any way, solely a gain—what 5 would you choose?

213K notes

·

View notes

Text

For anyone who’s ever wondered who they’d be in a 19th century novel

The wait is over: 19th Century Character Trope Generator

I’m “Meddlesome Bachelor with 2,000 pounds a year” yes please sign me up

33K notes

·

View notes

Text

I know this is a dumb takeaway to have from a work of classic lit, but I find Twenty Thousand Leagues to be rather comforting because the protagonist/narrator is this 40 year old unmarried man with no kids and that never comes up. He doesn't have a wife back in France, he doesn't have a long-lost love from his past, he's just some guy working in the museum and living in his little apartment next to the botanical gardens. Ned is also 40 and while it's mentioned that he had a fiance at some point, the fact that he is also unmarried and without children never comes up. He's just whaling with his buds.

And Conseil is constantly referred to as "boy" or "lad" and is definitely treated like the youngster of the group--and he's 30.

Idk. I'm turning 28 this year and I'm not in a relationship (and with my studies idk how to even make that work), so it's comforting to see that these guys had an established and comfortable life (pre-Nautilus of course) well past 30 without needing that. I can be alone with my fish. That's fine.

2K notes

·

View notes