Text

A Country Called Song

by Najwan Darwish

tr. Kareem James Abu-Zeid

I lived in a country called Song:

Countless singing women made me

a citizen,

and musicians from the four corners

composed cities for me with mornings and nights,

and I roamed through my country

like a man roams through the world.

My country is a song,

and as soon as it ends, I go back

to being a refugee.

130 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ozymandias

by Percy Shelley

I met a traveller from an antique land,

Who said — “Two vast and trunkless legs of stone

Stand in the desert… . Near them, on the sand,

Half sunk a shattered visage lies, whose frown,

And wrinkled lip, and sneer of cold command,

Tell that its sculptor well those passions read

Which yet survive, stamped on these lifeless things,

The hand that mocked them, and the heart that fed;

And on the pedestal, these words appear:

My name is Ozymandias, King of Kings;

Look on my Works, ye Mighty, and despair!

Nothing beside remains. Round the decay

Of that colossal Wreck, boundless and bare

The lone and level sands stretch far away.”

553 notes

·

View notes

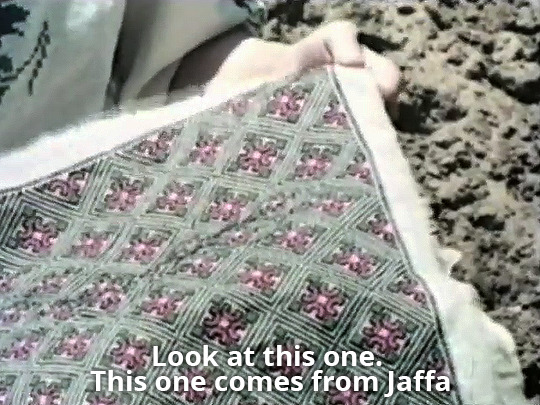

Text

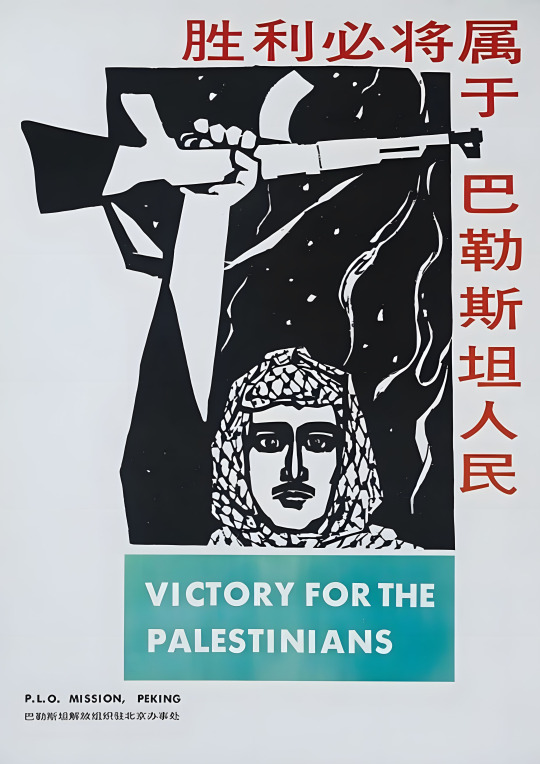

"Victory will surely belong to the Palestinian people"

People's Republic of China

c. 1970s

780 notes

·

View notes

Text

Egon Schiele

Selbstseher II (Tod und Mann), 1911

Oil on canvas.

113 notes

·

View notes

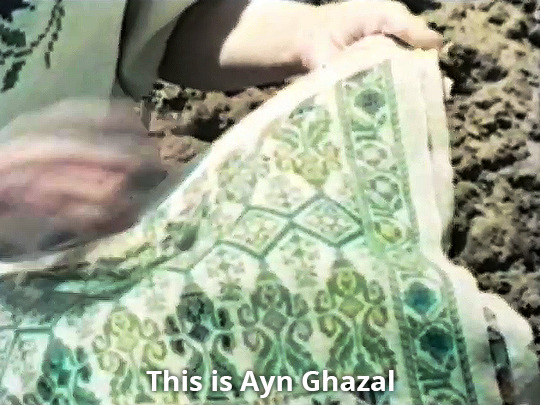

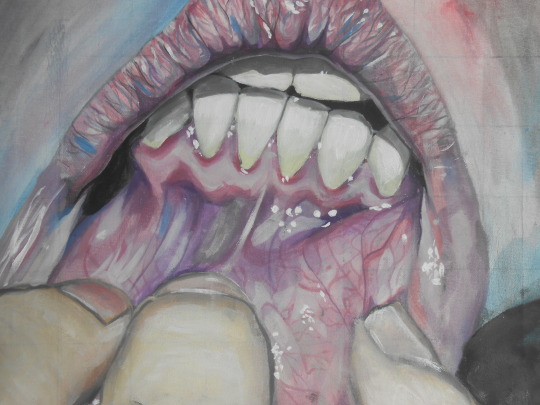

Photo

Probably should’ve spent more time on this but I like it as it is

37K notes

·

View notes

Text

Details from Jacques-Louis David, The Farewell of Telemachus and Eucharis, 1818.

0 notes

Text

Félicien Rops, Death at the Ball, ca. 1865–1875.

0 notes

Text

Readings, 2023

I didn’t read as much or as widely in 2023 as I had hoped, but what I did read mostly followed a through-line of free-spiritedness, pessimism, and absurdism as part of researching for a theory on the critique of everyday life I’ve been working on. This has involved reading more fiction than in the last few years, which I’ve definitely enjoyed, and finally getting around to several authors I’d been meaning to read for years. A fun reading year I’ve already begun furthering in 2024.

1. Camus, Albert. “Exile and the Kingdom.” Translated by Justin O’Brien. The Plague, The Fall, Exile and the Kingdom, and Selected Essays, by Albert Camus, Everyman’s Library, 2004 [1957], pp. 357–488

A strong collection of short stories, each full of a sense of unease, ennui, melancholy, estrangement/alienation, and even madness. I enjoyed them, though they never fully clicked with me. Above all, they felt substantial, considered, and carefully constructed; perhaps too carefully, as they all had a sense of detachment that seemed a little at odds with their subjects.

2. Machiavelli, Niccolò. The Prince. Edited by Peter Bondanella, translated by Peter Bondanella, OUP, 2008 [ca. 1513] (re-read)

Re-reading The Prince for a second time in less than six months (this time for a seminar rather than myself) was very enjoyable, which is a testament to Machiavelli’s literary skills. Some of the things which stood out to me on this reading more than on previous ones: Machiavelli’s artistic talent, the work being full of tight little sentences both beautiful and cutting; the metaphor of applied sciences (arts), above all medicine; the sheer ubiquity of his implicit republicanism; the degree to which he offers ethical maxims—in the tradition of Nietzsche or La Rochefoucauld—for life that can be more or less applied by anyone. My conviction of the centrality of this little book for all political reasoning, science, and practice only grows. An endlessly fertile work. Bondanella’s translation is tight, evocative, stylish, and still by far the best I’ve come across.

3. Anderson, Perry. Considerations on Western Marxism. Verso, 1979

An accessible and easy introductory essay for the tradition, striking a balance—mostly but not entirely successfully—between productive criticism and productive encouragement. However, Anderson fails and never properly even attempts, despite claiming he would, to establish the coherency and meaningfulness of the concept of Western Marxism itself, without which the work is a little disjointed.

4. La Rochefoucauld, François de. “Moral Reflections or Sententiae and Maxims: fifth edition, 1678”, “Maxims Finally Withdrawn by La Rochefoucauld”, “Maxims Never Published by La Rochefoucauld”. Collected Maxims and Other Reflections, by François de La Rochefoucauld, OUP, 2008 [1664–78], pp. 1–191

Technically sharp, tight, incisive; a wonderful representative of the aphoristic ethical tradition and a refreshing kind of urbane cynicism concerned with living well, i.e., with happiness. Very much begs for re-reading, especially because so much of it will inevitably go over your head on first reading, an inevitable risk of short (or even longer) aphorisms.

5. Cioran, E. M. A Short History of Decay. Translated by Richard Howard, Penguin, 2018 [1949]

Cioran is meant to be lyrically very talented, and certainly there are many aphorisms in this short work that are indeed artistically excellent, but there are also a lot (I’d say slightly more) which I found clumsy. I got the impression he was trying too hard and that where he succeeded it was as much from brute strength as learnt skill. Linked to this, philosophically speaking there were plenty of interesting ideas and themes, but they were insufficiently built upon; the aphoristic form was, I feel, misused here, and worked to undermine rather than reinforce the philosophy. The book felt underwhelming compared to his high reputation. Overall, a good book, definitely worth reading and both a notable product of its time and place and a work for the present, a more than worthwhile study of life’s groundlessness and aporias, but not the masterpiece I’d been hoping for.

6. Cioran, E. M. All Gall Is Divided. Translated by Richard Howard, Arcade, 2019 [1952]

A much stronger work than A Short History of Decay: artistically far superior, masterful in its hyper-short aphoristic form. Even through the prism of a translation, it’s clear that Cioran became much more comfortable writing in French in the three years between the two: the sentences run better, are more careful, more economical, more impactful. In terms of the philosophical content, having finished the book I feel unsure about what it was actually saying, as if it wasn’t saying much at all. I think this is a limitation of such short aphorisms when they're taken in isolation and not used as part of (perhaps prompts for) discussion, philosophy being an inherently dialogic art; I prefer the longer form used by the likes of Nietzsche and Adorno and, indeed, the Cioran of A Short History. Nevertheless, All Gall Is Divided picks up where A Short History of Decay left off, continuing the call for a moderate and moderating scepticism and rejecting fanaticism and faith. As ever, the pessimists are the more respectful and kind thinkers...

7. Althusser, Louis. Machiavelli and Us. Edited by Francois Matheron, translated by Gregory Elliott, Verso, 2011 [1962–86]

A fantastic study of Machiavelli and his materialism; an immensely strong justification of his absolute centrality for materialist analysis and politics. The reading of Machiavelli as the first theorist of political practice as such is especially strong and important, as is the closely related interpretation of his approach and practice as being one of locating specific, concrete conjunctural situations—exactly as a Leninist does—and, sub specie historiae, identifying programmatic tasks immanent in that conjuncture and establishing (and judging) means and aims only with reference to that task, not with reference to whichever subjectively-determined goals the political agent might have as he’s often thought to do (a “vulgar pragmatism”, Althusser calls it). A brilliant, short, essayistic book, strong both as an analysis of Machiavelli per se and (mostly implicitly) as a guide to how he can and must be used by communists.

8. Tartt, Donna. The Little Friend. Bloomsbury, 2002

I read this at random to try and get back into long novels after years of avoiding them, and hopefully it's succeeded because The Little Friend is a great book. Its central characters—especially the protagonist, Harriet, the best child character I’ve read in a very long time—are rich and convincing, its atmosphere and sense of place are perfect, and the sadness and misery which pervades it are excellently handled. The ending is delightfully brutal, a gorgeous flurry of violence. The social criticism that is present throughout just beneath the surface is also well used to set the mood and context, though I would say is a little underdeveloped and maybe somewhat crude, though the perspective of a child is responsible for a lot of that crudeness and so isn’t necessarily a weakness.

9. West, M. L., editor. Greek Lyric Poetry: The Poems and Fragments of the Greek Iambic, Elegiac, and Melic Poets (excluding Pindar and Bacchylides) Down to 450 BC. Translated by M. L. West, OUP, 2008

West's translation is often fairly loose in order to make the poems more comprehensible to a modern audience, and while that's usually something I don't like I have to say he's done a good job here. Arranging the poets chronologically (as much as is possible, anyway) really lets you see the cultural change that occurred over the centuries covered, as old, barbaric, Dionysian Greece gave way to a younger, more sterile, more civilised, more Apollonian regime. Throughout, however, the poets have a profound sense of intimacy and place, a true glimpse at a different way of life and the ephemeral pleasures of a long-gone world. The universal embracing of all the poets—from the oldest to the most recent—of sexual desire in general, without qualification of the sex of the target of that desire, is very stark, and a wonderful demonstration that our modern conception of sexuality is historically relative and must one day fall— we can only hope to be replaced by something much closer to the profound wisdom of the ancient erotic principle. Despite the translation's best attempts and the palpable skill of the poets, a lot of the work here does come across as quite dry, sadly, bereft as it is of its native metre and the accompanying music it was meant for, to say nothing of the social context it was written to be enjoyed in or the extremely fragmentary status of so much of it. But even so, there are throughout stunning fragments of beautiful verse, from little clusters of word combinations that seem to come out of nowhere to whole sustained works that, by some miracle, have come down to us through the millennia. I read this above all to get a better feeling for ancient Greek culture, and in this Greek Lyric Poetry succeeds: it is the collected beauty of a different way of life that can decisively inform our struggle for a new one.

10. Lucretius Carus, Titus. On the Nature of the Universe. Translated by Ronald Melville, OUP, 2008 [ca. 50BC]

Lucretius’ achievement in writing De rerum natura is difficult to comprehend. Simultaneously a powerful cosmology that is barely out of date and a guide to living which remains nearly peerless, it combines, as all good philosophy should, wonderful content with wonderful form, but the degree of his artistic skill is so total that it easily puts him at the summit of philosophical writing, alongside such giants as Nietzsche and Plato. This edition is very strong, with an excellent translation, a very competent introduction, and a large number of explanatory notes that are formatted in a way that doesn’t impact reading the main text at all. Why Melville has translated the title as On the Nature of the Universe, rather than the ubiquitous On the Nature of Things, I don’t know; it’s a strange choice. Maybe he wanted to emphasise the scope of the work, and the universe comes across as more magisterial than “things”? But his translation is excellent, very readable, beautiful.

The subtle, stunningly intelligent atomic physics that Lucretius communicates in such beautiful and evocative ways is amazingly prescient and perceptive. The degree to which it presaged central discoveries of modern science is exhilarating and leaves me a little speechless. To name only a few standout points from the first book: entropy (1.215); the conservation of matter/energy (1.215–25); relativism about time (1.458); molecules (1.483); subatomic particles (1.610). These are things which Lucretius hypothesises on the basis of a masterful combination of observation, experimentation, and reasoning, i.e., upon genuinely scientific grounds. The maturity and sophistication of the entire enterprise is staggering. Among the many, many things that Lucretius is, he is irrefutable evidence that the people who lived even in the distant past were not stupid, and knew how to discover fundamental truths about their world. In so doing he’s also a fantastic standard-bearer for philosophy: this is what our subject can do! See what we can achieve! See what we can know! See our triumph!

His more overtly “philosophical” principles are even more impressive, his atomism, no matter how stunning, being now (after millennia!) outdated. Among such vital and still cutting-edge principles as the causal closure of the physical (1.304) and determination in the last instance (1.546), Lucretius puts forward the genius of Epicureanism in full force: the harmlessness of death, the ubiquitous misery of fearing death, the ease and goodness of viewing death with ambivalence and contempt and carelessness; hedonism; opposition to romance as a social regime (something even Marxists haven’t fully recognised!); opposition to religion (the criticisms of religion in De rerum natura are extremely powerful and gorgeous, heartfelt and motivated by an intoxicating humanism and love and so disgust at the wound that religion is for men), and on and on.

I simply cannot lavish enough praise on De rerum natura. It comes within a hair’s breadth of perfection, being pulled down only by a brief lapse into misogyny and lazy, patriarchal thinking and the affirmation of marriage, something even more disgraceful as, paradoxically and contradictingly, it follows directly on from an unparalleled rejection of romance and the slavery it subjects us to. But even this is confined to a single page. De rerum natura is an entire philosophy for life contained in a relatively short book of poetry: it is a shining jewel of world literature and a defiant, proud demonstration of antiquity’s brilliance and bequeathment to mankind. It remains a live work, begging to be taken up and used in the critical study and critique of the world— communists could learn a great deal from it; Marx’s debt to Lucretius was a good starting point, but it has been criminally underdeveloped. Just beyond brilliant. “Masterpiece” doesn’t even begin to do it justice. Ovid gave some indication, made some attempt, when he wrote that ‘The verses of sublime Lucretius will perish only when a single day brings about destruction of the world’ (Amores 1.15).

11. Cioran, E. M. The Temptation to Exist. Translated by Richard Howard, Arcade Publishing, 2013 [1956]

A strong work of philosophical essay writing, a worthy addition to the French tradition in which Cioran is here attempting to place himself. Lots of interesting ideas skillfully expressed in easy and engaging prose. Cioran’s writing is tight, terse, and considered, and this book has confirmed my judgement from the previous two books of his I read this year that he’s a master of phrases—of little combinations or words—and that this is where his style really excels. In terms of content, The Temptation to Exist definitely has stronger and weaker parts, but rarely falls very far from “good”.

12. Amable, Bruno, and Stefano Palombarini. The Last Neoliberal: Macron and the Origins of France’s Political Crisis. Translated by David Broder and David Fernbach, Verso, 2021 [2018]

Read this in a couple of sittings over a single day, so a relatively easy read. Amable and Palombarini argue that the defining characteristic of the contemporary French social formation is the absence of a dominant social bloc (i.e. voting bloc, support for a party or coalition of parties), and that Macron and LREM are the first to have been able to capitalise on what they call the “bourgeois bloc” of the upper and middle classes who are united by “culturally left/liberal” views and support for European integration.

13. Thacker, Eugene. Infinite Resignation. Repeater, 2018

Infinite Resignation is very easy to read. I read over a hundred pages in a day multiple times, and that’s very unusual for me. I would describe Thacker’s writing style as distinctly “American”: plain, simple, best when it is saying something bluntly, and unsightly when it tries to be artistic and ape the European writers that dominate the book; he’s just not good enough an artist to sound profound when he’s writing a hyper-short aphorism full of pseudo-profound words. But for all this the book is not trivial, and Thacker’s encyclopaedic and constant reference to the long tradition of pessimism adds a huge amount to it. Overall a perhaps surprisingly effective work, one which I’m already in the process of mining for ideas and even some quotations for my main ongoing draft.

14. Lahiri, Jhumpa, editor. The Penguin Book of Italian Short Stories. Penguin, 2020

This is a wonderful anthology, full of magic, the fantastical, the strange, the sombre, the melancholy, the poor and the intelligentsia, the city and the countryside, the new and the old, the male and the female, the human and the nonhuman. The selected stories are all excellent, and together convey a really strong sense of Italy and her regionalism, and of it changing over time, with selections from across her modern history as a unified state. There are stories here which are works of unpolished social realism; there are also a large number which come across as something like a fable. All of them make you want to be in love with such an ancient, rich, cultured, and conflicted country, even and especially when you are being shown her ugly underbelly.

15. Kafka, Franz. “The Trial.” The Complete Novels, by Franz Kafka, translated by Edwin Muir and Willa Muir, Vintage Books, 1999 [1915], pp. 11–128

What can one say of Kafka, other than that he is gorgeous? The Trial is a powerful critique of liberalism and capitalist modernity, with the entire system and its well-meaning participants (we might say its bearers— Träger) undercut and subjected to a scathing demystification through the mystifying story. Some interesting things that stood out to me: Joseph K. is unusual for a protagonist in being a very unlikeable person, nothing remarkable but distinctly distasteful and offputting, as well as being the quintessential modern bourgeois; throughout the novel, its recurrent subjects/themes cover, like bullet-points, the central foci of capitalist modernity, most prominently the judiciary and legalism, general bureaucracy, landlordism, the marriage form and monogamy, misogyny/patriarchy, and the interplay between poverty and wealth and their common subjection before the social order itself. The way that Kafka combines form and content is masterful, as the two are always fully in agreement and mutually reinforcing. Even when the gruelling monotony and byzantinism of most of the novel give way without warning to the stochastic, fragmentary, disjointed ending, a product of the book’s incompleteness, it seems almost designed and deliberate, and has a strong emphatic effect.

16. Shawn, Wallace. The Fever. Revised ed., Faber & Faber, 2009 [1990] (re-read; new edition)

The Fever is a brutal work, an emotional powerhouse. It has an amazing power to make you viscerally bleed for the poor and the oppressed, for the downtrodden, for the forgotten and the exploited, and to want to give everything you are to the people and the struggle for freedom. It’s especially cutting for a middle-class reader like the protagonist, for the well-off, for those who think of themselves as good people, because it rips the edifice of money and morality and the liberal order out from under their eyes and shows how the whole regime of wealth and comfort rests upon the backbreaking humiliation and misery of the poor. It’s a cold-hearted, ideologically suffocated person who could read The Fever and not be deeply moved by it and made, even if only for a brief period, to see the world a little differently. Short, sweet like vomit, oppressive like the monsoon heat, it’s a brilliant little play.

I don’t like or agree with several of the revisions made in this edition compared to the original (which I read many years ago); maybe that’s because some of the lines of the original which have been burned into my mind have been erased or altered, but some of the central moments of the play—most of all the little church in the poor country, and the guerilla in the café—seem to me less powerful and direct.

17. Nietzsche, Friedrich. Human, All Too Human: A Book for Free Spirits. Translated by R. J. Hollingdale, CUP, 1996 [1878–80]

A fantastic work that is a brilliant life companion for the titular free spirits. It’s wonderful to see Nietzsche as a critical but sincere advocate and follower of the natural sciences and the Enlightenment. This is a somewhat short review compared to some of the others on this list, but don’t mistake that for a lacklustre attitude towards the work on my part: it’s more than anything because there is so much—and so much that is good—in these “travel books” as Nietzsche called them that I struggle to think of where to begin with describing them. They are immensely valuable, as is everything by Nietzsche, but spending half a year slowly chewing through these couple of thousand aphorisms has given me a lot, and a huge pool of ideas and references for my writing. They do exhibit marks of underdevelopment, both in content and style, compared to his later, “mature” works, but nonetheless they amount to a very valuable salvo against the world we oppose and of considerable worth irrespective of their place within Nietzsche’s oeuvre.

18. Camus, Albert. “The Myth of Sisyphus.” Translated by Justin O’Brien. The Plague, The Fall, Exile and the Kingdom, and Selected Essays, by Albert Camus, Everyman’s Library, 2004 [1942], pp. 489–605

For a work as famous as this is, I wasn’t very impressed by The Myth of Sisyphus. It seemed to me more like an extremely bloated plan for an essay rather than a finished one, complete with critical, central failures, including a failure to ever properly define or characterise vital concepts (including the absurd!) and to even attempt to justify enormous leaps of “argument” (without justification they’re not arguments, only stipulations at best) that are essential to the essay as a whole, most notably the rejection of suicide which is made with a handwaving nonentity of a segway into the rest of the work. The huge amount of space given over to the analysis of works of literature also seemed wildly misplaced and detracted from the essay; the substance of what Camus is arguing with them could be stated in two pages. I agree with a huge amount of what Camus is saying here, just not with really any of the ways in which he is stitching those things together. Reading this has sadly reinforced my preconception that Camus was a good philosophical novelist but a poor philosopher (a distinction he actually conveys well in this essay, ironically enough, including the weakness of the former group’s attempts to fulfil those of the latter— I can’t tell if he thought he was subject to those weaknesses or not, but he was). Nevertheless, the philosophy being put forward here is a strong one, a distinctly Mediterranean foil to the Germanic Nietzsche. The discussion of absurd archetypes, namely the seducer, the actor, and the conquerer, was a particular stand-out that I think offers good strategies for different free spirits. I have been utilising The Myth of Sisyphus a lot in scraps of writing towards my main ongoing piece, I want to emphasise the significance and maturity of its ideas, but as a piece of writing it’s surprisingly poor and lets down its actual position considerably.

19. Camus, Albert. “The Plague.” Translated by Justin O’Brien. The Plague, The Fall, Exile and the Kingdom, and Selected Essays, by Albert Camus, Everyman’s Library, 2004 [1947], pp. 1–272

The first chapter of this book has one of the best atmospheres I’ve ever read, a near-perfect building of tension and dread that masterfully begins a masterful story. The teaching of philosophy—and of a philosophy—through fiction is difficult, and in my experience fails more often than it succeeds, but Camus has succeeded to such a degree in The Plague that I’m left feeling like a novel was the best way to present the ideas, stronger than a nonfiction work, stronger than The Myth of Sisyphus. Beautiful and brilliant, the sort of work someone can easily pick up, be awe-struck by, and decide to adopt as their guiding document in life— and be well-chosen in doing so. Everything is as it should be, and the cumulative effect is something like perfect. A sublime book to end the year with.

1 note

·

View note

Text

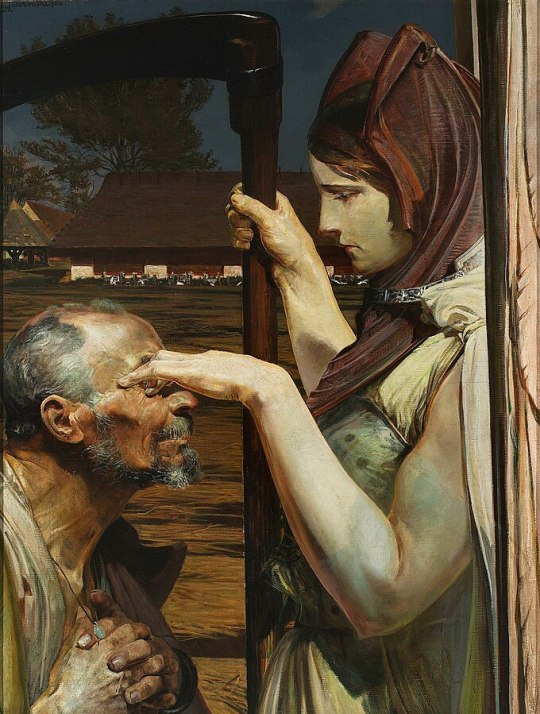

Jacek Malczewski (1854-1929)

"Death" (1902)

Oil on canvas

Symbolism

Located in the National Museum, Warsaw, Poland

422 notes

·

View notes

Text

A rare early 19th-century photo of the Great Sphinx from a hot air balloon. This is before it was excavated and restored

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Pictures of the Old World, Dušan Hanák, 1972, Czechoslovakia

97 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Sun postcards compiled by Dick Seeger (1980) PNGs.

(source)

14K notes

·

View notes