Link

Some Syrians who have fled as far as Morocco seeking refuge have joined the African migrants camped out on the Moroccan side of the fence setting apart the Spanish enclave of Melilla.

0 notes

Photo

Adorable picture of my friend JP's Moroccan host brother. I cannot wait to see what other beautiful images appear on this blog, mostly so I can relive my experiences in Morocco.

My brother Islam

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Photo credit on the SIT Morocco: Human Rights and Multiculturalism webpage — I took this picture of a worker who was squeezing argan oil from paste at the women’s cooperative Marjana. Check it out!

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

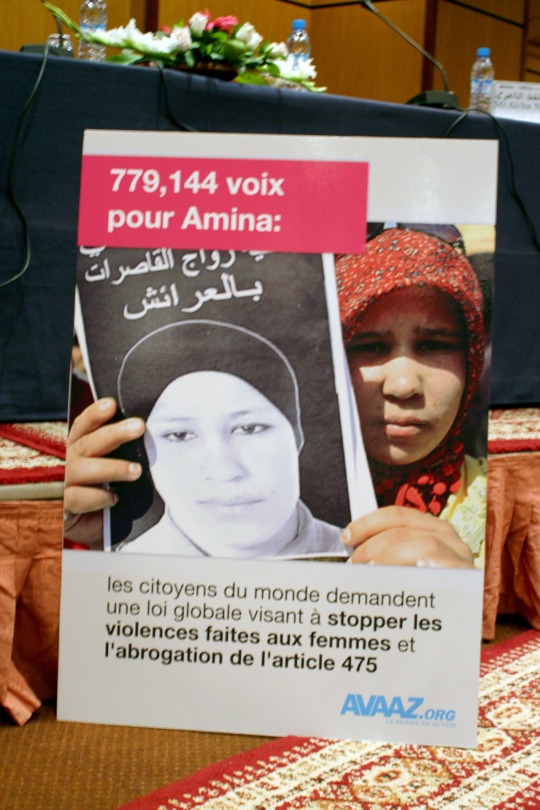

A stack of hot-off-the-press pages was steadily growing on the print shop’s counter. After three weeks of research on rape and underage marriage in Morocco, the 42-page document containing the findings of my Independent Study Project was finished — almost.

When you’re asked to conduct research in a country where you’ve only lived for four months, and in a short time frame of 21 days, the chances of the end product being quality and truly reflective of the question under investigation are slim.

The death of 16-year-old Amina Filali on March 10 sparked my interest in looking at the inefficiencies in Moroccan legislation as it pertains to protecting the rights of women and children who are victims of rape. But it wasn’t until the news of Amina’s death gained international media attention and caused political controversy that I truly considered the topic to be research-worthy.

While was eager to talk to conservative Islamists and progressive activists and feminists in order to examine the “two sides of the debate,” I learned that such an approach would not be entirely reflective of the larger issue — it would only restate what most of the news articles and television broadcasts were saying. So instead I set out to find out what they weren’t.

I began by seeking out sources quoted in most news articles — presidents of feminist NGOs, human rights lawyers, ministers of the Islamist Party of Justice and Development — and maybe even some victims of violence themselves. But I quickly hit a roadblock.

I learned two things from my research: 1) not many of the “big” people give priority to interviews with American student researchers, and 2) rape is still a cultural taboo in Morocco.

But after speaking with religious scholars, political scientists, feminists, activists and even some Moroccans I met during my research period, I learned more about the root issues of the debate and how Amina Filali’s case revealed a larger problem: The country’s symbolic “achievements” for women’s and children’s rights —the newly reformed constitution (2011) and Family Code (2004), and some international conventions — hardly reflect the reality of these individuals, specifically ones that are victims of rape.

Though my research provides context to this issue and I’ve come to some general conclusions about what could happen in the future, I wish I could continue conducting interviews and use other methods for another six months to see what sort of change the current government will (or won’t affect) in order to improve victims’ situation in Morocco.

In my opinion, research shouldn’t have a definitive timeframe — especially a mere three weeks. This, I fear, leaves room for criticism, seeming neo-imperialist in the analysis, misinterpreting data and jumping to conclusions (and often false ones).

For what it’s worth, my research project skims the surface of the culturally rooted problem of the marriage of minors to their rapists, which has infiltrated the Moroccan political sphere, and explains the reasons for its societal justification. Only time will tell whether the Amina Filali case will trigger a renewed urgency in society to break the silence around rape, challenge the status quo and push the government to uphold its (written) commitment to protecting human rights.

12 notes

·

View notes

Photo

So remember that time we ate shark?

Now that the research period for my Independent Study Project has begun, I have moved out of the old medina and said goodbye to my homestay family — except when I visit for Friday couscous.

Because my research examines the political discourse around the recent case of Amina Filali, and the demands of civil society to reform legislation contributing to the phenomenon of underage marriage and marriage of minors to their rapists, I chose to stay in politically dynamic Rabat.

However, I left the whitewashed walls and twisty impasses of the old medina and moved into a beachside apartment in the kasbah with a few friends from my program. Since we no longer have our homestay families to share meals with — or our Moroccans mothers to cook us incredible tagines or bake hersha and rif for teatime — the roommates and I have been whipping up whatever recipes we can with ingredients we buy from the vegetable souk and local marchie.

We have made everything from sautéed eggplant, cucumbers and onions medleys and stir-fried chickpea, tomatoes and pea dishes, to cinnamon-infused rice and La Vache cheese omelets. In lieu of a baking oven, we’ve used the stovetop to pan-sear cake batter — and prepare a surprisingly fluffy albeit toasty chocolate cake. We’ve also picked up mystery meat from vegetable street… only to realize after 45 minutes of it still sizzling in the skillet that we probably should have picked up sardines instead of a half kilo of shark.

While I’ve been enjoying every bite of my lemon-and-peppered green bean, cucumber and carrot salads and juicy orange-and-apple breakfasts, I’m a bit disappointed I didn’t have more time to spend in the kitchen with my host mother and learn Moroccan cuisine. At least I have a knack for preparing traditional tea: a palm-full of dried pellets, a couple twigs of mint leaves and a few spoonfuls of sugar.

The more time I spend in the kitchen, the more excited I get about going back to the souk where local, fresh foods abound. While the cost of living and shopping locally is far less expensive in Morocco than it would be in the U.S., I’m looking forward to visiting the Farmer’s Market and possibly looking into CSA shares upon my return to Ithaca in the fall.

Goodbye dining halls and Terrace dorm buildings! Hello apartment kitchen, fresh groceries and a gradually building recipe book with inspirations from Morocco.

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Head dangling and tears rolling down her face, I outstretch my arm to console hers — smeheelee. She looks me in the eyes and leans forward, her wet cheek presses against my right one, then the left one. Our eyes meet once more before she nods her head into a bow. Droplets weld in her eyes, and I can feel her pain — the pain of losing her daughter who committed suicide after an unwanted to marriage to her rapist.

Today was the 13th Annual Tribunal Hearing sponsored by l’Union de l’Action Feminine. This year’s focus was “Stop the Infanticide of Our Children.” The tribunal was a space for victims to voice their sufferings, a place to listen to their testimonies, and an opportunity to raise awareness and change the mentality of Moroccan society – the one that these feminists argue enhances crimes and injustices by not respecting the childhood of young girls.

Considering the waves of change that have spread across the Middle East since the Arab Spring, this tribunal was held in the context the new 2011 Moroccan constitution, which promises parity, justice and non-discrimination. These feminists, however, believe the application of these constitutional decrees is inadequate.

“This is not neutral tribunal. It’s a tribunal on the side of the victims; it’s on the side of legality, justice, equality, women’s rights and citizenship to women as human beings.”

These were the words of the UAF President and tribunal mediators who passionately opened the hearing — in Darija. I relied on my new friend Fatima Outaleb, director of the UAF, and some French-speaking audience members next to me, for translation.

From the rural village of Laracheto the urban capital of Rabat, the diverse range of testimonies illustrated how the rape of minors touches every corner of Morocco — and is tearing apart families and forever altering the futures of these young girls nationwide.

Article 475 of Morocco’s penal code allows for rapists to escape persecution by marrying their victims — on one condition. The family of the victim must agree. While this applies to women of all ages, it is common among minors like Aminia Filali, the 16-year-old who committed suicide last month after seeking an escape from a forced marriage to her rapist. Her parents testified on their daughter’s behalf.

While Amina’s father recounted the story of Amina’s kidnapping and rape, and their pursuit of finding her. Only after a formal testimony did her mother interject – wailing for justice and pleading that the man who “killed” her daughter go to jail.

The problem lies not only in the laws that legitimate the marriage of rape victims to their rapists, but also in the culture that doesn’t perceive childhood as something worth protecting. Rather, the advocates at this tribunal believe society presents young girls who are victims of rape as sacrifices to their perpetrators. They believe society banishes the raped girl by taking away her youth, by shorting her education and then by legitimating her marriage to her rapist.

The UAF and other feminist organizations, along with the men and women who came to the tribunal in solidarity, believe that this is a crime against humanity. They believe this tribunal should inspire victims to bring their cases to international courts, not just national ones.

A strong demonstration of this will was the testimony of Esma, a mother whose 13-year-old daughter was raped and nearly forced into an unwanted marriage. After she brought her daughter’s case to court, the judge gave the perpetrator one choice: marry the victim or go to jail. Esma considered marrying her daughter to the 21-year-old man. She thought it would be less shameful to say that her daughter was married and/or divorced, than to acknowledge her loss of virginity. But after her daughter tried killing herself, Esma intervened. Unfortunately, her daughter’s rapits still roams freely; he was never jailed.

“You are all parents. I’m a mother who is burning, suffering, speaking on behalf of my daughter who lost her future. He is not punished.”

Hands clapped. Feet stomped. And the room chanted a response to her cry: “The victims are here. Where is the justice?”

In a society where virginity is sacrilegious, discriminatory laws and articles like 475 of the penal code and Article 20 of the Moudawana (which permits a judge to overrule Article 19, which forbids marriage under 18, in certain “situations”) still exist. They do not recognize the rights of a woman as equal to those of a man, or the rights of a child.

But with the global attention given to Amina Filali’s death and a critical and building pressure on the new government to respond, feminist groups like the UAF, civil society actors and other NGOs are beginning to create more space for public debate and opportunities for raising awareness — and lifting spirits.

Ending the event on an optimistic note, 475 hands tightly clasped 475 balloons, which symbolized the lost lives of young victims of rape and forced marriage, and released them into the sky, promising to keep up the fight for their freedom by demanding the reform of Article 475.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Feen Beb Boujloud? …

… was the question we repeated every 5 minutes on our trek from the train station in the nouvelle ville to the famous entrance to the medina kadima of Fez.

The three-hour train ride from Rabat — along with the light spattering of raindrops — begged for a brisk walk to the riad where we would spend the night. After walking in sharp “L”s on sidewalks that roped around the tall and rectangular taupe walls enclosing the old city, we entered into the heart of Fez.

Cobbled stones met our rain-kissed toes underneath the royal blue archway leading into the medina. Cafés and hanoots welcomed us with roasting dijej (chicken) and freshly baked hubz (bread). Twists and turns through narrow zilnkas (pathways) guided us to Riad Al Akhawain. Upon entering our thirst was quenched with hot mint tea and our tummy grumbles were silenced with delicious peanut-butter filled and powered-sugar topped cookies.

Friday is a religious day in Morocco, so most businesses close up so shop owners can attend mosque services and rest at home with the family. Thus, our early evening outing in the medina consisted more of exploring pathways than any shopping or site seeing. Amid our wandering we tasted sweet nougats, saw a chicken wandering in and out of a café, and found a charming place for dinner. My 70dh ($9) meal of mint tea, harira (soup), chicken tagine, and fresh oranges and strawberries topped with brown sugar was worth every bite!

Our night in the riad was full of laughter and surprise as the nine of us gathered into one of our rooms, sharing snacks and drinking to memories made throughout our time here in Morocco.

The next morning we set out to explore the streets and shops of Fez. It wasn’t long before the contrast of pure whites and rich blues caught our eyes and lured us into a beautiful ceramic shop. Plates, bowls, tiles and decorations donning the traditional colors of Fez (blue and white) along with traditional Moroccan and Berber designs lined the shelves and walls.

After some “difficult business” — which we were, according to the shopkeeper, Mohammed — our attempts to bargain in Arabic and learn from our newly made friend won us a visit to the terrace. We climbed at least three flights of stairs to reach the terrace that overlooked the city of Fez. Below, we saw one of the famous tanneries and University of Al-Karaouine, which is the oldest university in the world.

Later on, a woman led us deeper into the medina to one of the tanneries. We climbed to the terrace to look down upon the workers dipping hide into wells with dyes of different hues of brown and red. While Fez is famous for its leather, we spared our wallets from the jacked-up tourist prices of these hand-made goods.

The rest of our afternoon was spent in and out of shops where we conversed with many owners who told us stories and inquired about our studies in Rabat. These interactions put my language abilities to the test; and I’m confident to say I passed. I was incredibly excited by my ability to speak Darija well enough to construct simply sentences to convey my feelings about Morocco and what I’m studying here.

After two months of learning Arabic (Darija) in the classroom and gaining daily exposure at my homestay, I have grown to value the benefits of immersion. Without living each day like some Moroccans do and engaging with the culture, I doubt I would have been able to pick up the local language as quickly as I have. While I may not be able to speak for hours on end, formulate grammatically correct sentences or comprehend word-for-word what people say, each day and every travel experience are only helping me improve.

0 notes

Photo

There is novelty in the quaintness of Moroccan rural village life: resting under olive trees to escape the afternoon heat, herding sheep in the fields, fetching water from the communal well. However, exposure to this “foreign” livelihood brings on many physical, mental and emotional challenges — especially as an American student.

Hours after my arrival to the village of Beni Kolla, an immediate challenge was trying to determine my role in our mini-immersion experience. Was I there to learn? To teach? To share? To engage? To compare and contrast? A mixture of them all?

After 4 days in the village, I brushed the surface of discovering an answer.

The communication barrier was definitely a social challenge that complicated my emotions and my ability to express myself. Unlike Rabat, this village speaks a different dialect of Darija. It has influence from Berber tribes tucked away in the northern Rif Mountains as well as the semi-metropolitan area of Ouezzane (about 20 minutes away). As a result, the older generations of villagers speak a dialect that their children (like my host brothers and sisters) often had to translate into standard Darija or Fus’ha for us to understand.

Since I’m only just beginning to learn Darija — and I couldn’t rely on French as backup to communicate — it was especially difficult living in a house with two other students who were more advanced in Arabic than me. Rather than being encouraged to practice Darija, I was given translations from another student who is a native Arab speaker. While this was incredibly helpful for my understanding, I wasn’t challenged (linguistically) as much as I had hoped. But I did use little expressions and simple phrases to demonstrate my willingness to learn and communicate. Still, the language barrier seemed to prevent my host Mom and two teenage sisters from connecting with me on a deeper level.

My next challenge was completely shedding my Western expectations and preferences. Staying in a house without plumbing and only necessary furnishings (1 bed, 1 couch, 1 bureau to store 6 people’s clothes, a few tables, a stove, and a fridge, etc.) helped me gain an appreciation for minimalist living. This family shared its resources with others living in the village. It made me feel somewhat frivolous for using my basic travel items like bottled water, soap, makeup and toilet paper.

Some physical challenges included harnessing the family donkey to fetch jugs of water for the day, and trekking for 30 minutes in the blazing sun along a dry and dusty road to reach the elementary school.

During our stay, we learned that education is only offered until the sixth grade. Many children, especially girls, do not continue their studies because of the cost of transportation and the lack of familial connections in larger cities. Also, girls like my two teenage host sisters — who help their mother work in the field, upkeep the house and take care of their younger brothers — cannot afford to leave. We also learned that rural teachers often come from nearby cities where no public transportation runs to and from the school, so class is not always predictable. Also, when teachers are assigned to work in a village, they perceive this as “punishment.” This makes it all the more challenging for some teachers to motivate themselves to provide a good, consistent education for the children.

This was only one of many cultural and societal elements I had to come to terms with. It was hard to accept how certain privileges and freedoms I take for granted are not provided in some villages like Beni Kolla. I had to recognize that, for now, I cannot change these circumstances: My purpose was not to go to the village and change the people’s way of life. Rather, my role was to understand a different way of living and leave a positive impact and impression there.

I ultimately learned that my place, as an American student visiting in a rural Moroccan village, is to ensure that I — an embodiment of Western “power” — don’t make the villagers’ lives seem meaningless. I am privileged to live a life free of what I perceive to be their hardships. But my Western construction of these “hard tasks” — milking cows, herding sheep, making yogurt and fetching well water — are merely part of routine, daily life in the village.

In order to facilitate a means for mutual and cross-cultural understanding, I still have to work harder on putting aside my personal preferences and Western norms. I truly hope that my effort to be engaged, positive and immersed in this culture left a positive impact, and that my questions and interactions helped facilitate a means to dispel myths about Americans and Moroccans, and some of the barriers still cast between them.

0 notes

Photo

What was different about the way some Moroccans celebrated the international day of women this year? Hundreds hit the streets of Rabat to march in Morocco’s first SlutWalk.

Unlike most American SlutWalks, which sprang up all over the country in solidarity with movements that want to end victim blaming in cases of rape and sexual violence, Morocco’s walk demanded an end to the violence of inequality between men and women.

Pre-march rallying and inspirational speeches calling for an end to violence and more gender equality engaged a crowd of both marchers and passersby: The powerful rhetoric of speeches begged women to question “Bishall? … Bishall?” (“How much? How much?) they are willing to take from men while the energized rhythms of songs captivated those clapping along and chanting for stronger government intervention.

Organized in partnership with Woman Choufouch, a movement against sexual harassment, this “l'Moussawat lyoum 9bal Ghedda” movement adapted the globalizing SlutWalk march to fit its own local context. Specifically, this movement targeted the contradictions within the latest reforms to Morocco’s Constitution (July 2011). Despite the promise for gender equality and promotion of human rights, the weak implementation of these clauses is allowing discrimination against women to persist.

At the rally, university students like Ilyas (pictured above) shared their insights about changes that still need to be made before Morocco can see true gender equality. Some challenges include conservative resistance to Western ideals, which purportedly threaten Islamic principles. This notion has impeded some of the more “liberal” demands for gender equality. Other challenges include political parties that are promoting the false notion of women not wanting to be active in politics. Perhaps this is one tactic used to justify having only one female minister in the nearly — for she is the exception — exclusively male parliament.

After speaking with more women of all ages and races participating in the march, I discovered the wide range of demands unifying this demonstration. One woman wants the freedom to strut naked in the street and even to become king. Others want a better education system to increase public consciousness and change the male-dominated mentality of Moroccan society, which they believe is at the root of unemployment and unchallenged gendered construction of the woman’s “domestic duties.”

These beliefs reflect the societal discouragement Moroccan women — like many of their international sisters — face from participating in politics and exercising their freedoms in both the public and private sphere. Without gender equality, recognition of human rights and the safeguard of personal dignity, it’s hard to envision how a society that purports to be democratizing can propel forward.

Hopefully, movements like “l'Moussawat lyoum 9bal Ghedda” will continue to encourage Moroccan men and women to work in solidarity and put pressure on the government to give more priority to protecting and promoting women’s rights and dignity.

0 notes

Text

Mr. & Mrs. U.S. Ambassador come for tea time

One benefit of studying abroad in Rabat, which is both the capital and the political center of the country, is having prominent access to ministers, members of parliament and even the U.S. Ambassador to Morocco.

Ambassador Sam Kaplan and his wife, Sylvia Kaplan, came to speak to about 40 of the American students studying at the Center for Cross Cultural Learning. Over some tea and cookies, the two eloquently led a casual dialogue covering their personal experiences in Morocco, U.S. diplomacy efforts, national economic crises and influences of the Arab Spring.

One of the most important takeaways from their talk was the point that, as Americans, our standard of reference here cannot be the same as it is in the United States. This is simply because we’re in an entirely different country that has its own government structure and rate of development.

How does a country like Morocco develop democratic traits around a traditional monarchy?

Ambassador Kaplan discussed how despite lacking a separation of powers, the king’s efforts to include a human rights discourse into the new 2011 constitutional reforms is truly compelling. And, in the wake of the Arab Spring, the concept of transparency is very high right now.

Women’s leadership in NGOs is emerging and learning English has become an escape route from poverty for many Moroccans. Nevertheless, domestic issues of sovereignty in the Western Sahara and economic underdevelopment persist.

And feeble international efforts don’t help improve the country’s situation either. The U.S. has a strong trade partnership that makes it Morocco’s 4th trading partner. Yet Morocco ranks 70th on U.S. foreign imports. Furthermore, the distribution of U.S. aid for economic development projects like the Millennium Development Plan is unregulated by American agencies. Rather, the funds are dispensed to Moroccan agencies that choose where to allocate them.

According to Ambassador Kaplan, the U.S. Embassy in Morocco is working to strengthen bi-lateral relations and economic ties. These efforts have the potential to greatly improve international diplomacy, promote cross-cultural understanding and build partnerships for building a better future for all countries.

0 notes

Photo

The moment we touched down in Marrakech, all academics and formal group sessions went out the window — we were here as tourists.

We tossed our suitcases in the hotel room, claimed our beds and quickly touched up before heading out to explore. Marrakech reminded me of any urban tourist city in Florida. Unlike the old medinas of other Moroccan cities, the streets were lined with brand-name shops, knock-off brands and palm trees donning oranges.

Our first stop was Djemaa el Fna, the largest traditional souk in Morocco. We entered the main square where henna artists, snake charmers and monkeys attracted crowds of tourists. Stands of dried fruits and nuts as well as freshly squeezed orange and pomegranate juice encircled the nonstop bustling. From morning to night this square is packed with people selling everything from leather bags and wooden crafts to scarves and musical instruments.

After a full day’s worth of shopping in the sun, we trekked back to the hotel. On the way, we stopped at the grocery store to spend our 50 dirhams (~ $6) for dinner. I successfully bought a loaf of bread, a jar of hummus and some yogurt — not the most appetizing meal I’ve had since my arrival, but filling none the less.

Given some time to digest, we hit the town to experience the nightlife (on an off-season Tuesday) in Morocco’s most touristic city. African Chic was our destination of choice. Sooner after arriving, we realized we probably could’ve done better: A reggae band was playing a mix of Bob Marley, oldies and new pop. The drinks were fancy looking, but over-priced. And the crowd was comprised of mostly old European men and scantily clad Moroccan women entertaining them.

Our failed outing led us to dip out before 1 a.m. — a no-no for most Moroccan standards — and instead to hit the hay to prepare for another full day of site seeing and attempt #2 at living up the night.

To kick-start the day, I took a brisk morning run — only my second since I’ve come to Morocco, no thanks to my perpetual sinus congestion and minor verbal harassment each time I walk the streets. After a filling breakfast, hot shower and fresh outfit — something I take for granted changing into every day back in the U.S. — it was back to souk.

We set out to find the Saadian tombs before sundown, but to our dismay — and misleading schedule listed in our guidebook — we were about 15 minutes short of the site’s closing. Instead, we found a tiny café, took over the rooftop and watched the sun go down and scatter hues of pinks and oranges across the blue sky.

Within a few hours, music was blasting, cameras were snapping and the ladies were getting ready for a real G.N.O. After warming up at Gossip, a very posh and modern bar, we called the cabs and sped to Theatro, Morocco’s best nightclub since 2004.

As the first gaggle of girls at the door, the bouncers waived our individual entry fees (200 dirhams) and sent us in — masheemooshkee (no problem). We claimed a table, watched the clock and felt the beat gradually increase with each subsequent song. No soon after we were shaking what our mamas gave us to Ke$ha, Chris Brown and some African hip-hop mixes.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

After waking before dawn to watch the sun rise over the desert dunes, we boarded the bus to begin our journey full of twists and turns into the High Atlas Mountains.

We took a particularly winding descent down the first lull of rocky, cavernous mountains in order to reach the sand-colored gorges of Tineghir — similar to those in Ithaca, but without the emblematic grey tones — for lunch in the oasis.

Sadly, I didn’t get to try the goat tagine or eat any of the lush salads or bountiful fruits — my stomach caught its first bought of food poisoning…

This also means I spent the remaining 4 hours on the bus cradled in my seat, holding my stomach and dozing off before reaching our destination for the night: Ouarzazate.

Here, we would spend the night at Dar Tallyba, which is one of three dorm-like residence buildings for female students. These college-aged girls (most averaging between 18 and 22 years old) come from rural villages or small cities on the outskirts of Ouarzazate where higher education facilities are either of poor quality or nonexistent.

After lots of Imodium, water and a naz schwia (nap), I motivated myself to socialize with the students of Dar Tallyba. I was fascinated to hear their firsthand accounts of what it’s like to leave their small villages or rural areas for an extended period of time to pursue education.

I was fascinated with this concept. I wanted to know more about how in a country where culture, including law and religion, is centered around family life — especially in or Berber areas rooted in communal traditions — some families are investing in their daughters’ futures. Not only does this mean one less domestic worker is in the private sphere of the household, but also that liberal tendencies — higher education for females — seem to be permeating even the remote, rural regions of Morocco.

With a mix of Darija, French, Spanish and English tossed around the dinner table, the American and Moroccan students at my table were all able to make introductions, talk about our travels, delve into our personal (and even love) lives and snap a few photos for keepsakes.

The next morning we said our bislemmas (goodbyes) and trekked back up the steep roads into the High Atlas region. Along the way, we kept our eyes “peeled” for date, walnut and almond trees native to the region. By mid-afternoon we would make our long-awaited arrival in Marrakech.

0 notes

Photo

Arabian Nights

I’ve never been off-roading — until this week.

To get to our desert palace — or at least that’s what I think of our hotel, Auberge du Sud, in Merzouga — we took Landrovers across some rocky rumble and over small sand dunes before reaching mounds of sand too finely grained for any four-wheeler.

The six-person rovers rolled across the land, racing one another to our final destination. Before meeting our camels, we stopped at the Hassilabied Association. This is one of three other associations that work to educate divorced, widowed and single women in order to help combat Morocco’s illiteracy problem. In turn, these women are able to count money while shopping in the souks, help their children with homework and live more independently.

After 30 minutes of rolling, anticipation built as the rovers sped toward the first visible site of civilization. The small village of Merzouga was built up with mud-and-hay lathered rectangular structures like in Medelt. However, the golden dunes protruding from behind were unlike anything else I have yet to see during my time in Morocco.

No sooner after we parked the trucks was I straddling my camel, Hamoo, and trotting over the sandy beds of the Sahara. Our camel leaders, Mohamed and Ali Badi, brought us deeper into the dunes just before sunset. After 20 minutes, we demounted our camels and climbed some peaks to watch the sun descend for the night. Despite the lifelessness of the desert, it has the most serene, tranquil and peaceful aura. In all its vastness is also the greatest silence I have ever heard.

After our camelback ride, we were given tea and nuts before a grand dinner — as all Moroccan meals have come to be — of soup, cold vegetable salads, chicken tagine and fruit. Later, we danced to the sounds of traditional Gnawa music. The metal clappers and goatskin drums made a fast-paced beat, perfect for hip swinging, hand clapping and quick feet jabs.

Sleepy-eyed and sore from rough riding our one-humped friends, we all laid atop the terrace and said goodnight to a star-filled sky — only to wake up a few hours later to watch the sunrise over the dunes.

0 notes

Photo

Monkeys and donkeys and camels, oh my!

Saturday morning, we departed for our first of two weeklong excursions across Morocco. By 8 a.m. we loaded the bus, pulled out of Rabat and made our way across the Mid-Atlas Mountains.

After a few stops and about 5 hours later, we made our first stop was in a wealthy city southeast of Rabat called Ifrane. The snow-capped mountains, forceful winds and beaming sunshine stood in sharp contrast to the sandy shores and palm trees lining the walls of the old Rabat medina.

We met with college students of Al Akhawayn University, which we learned was the first North American style university in the Middle East — it was just built in 1995.

I felt as though I were a high school junior again, going on another college tour as the student ambassadors took us around the small, 1000-person campus. Here, all the classes are taught in English, which was clearly reflected in the students’ fluency — and this is in addition to speaking Darija and French.

After saying our goodbyes and filling our tummies, we hopped back on the bus and drove through the snowy mountains. Through the windshield wipers dusting away the flakes of snow, we could see skis, snowboards and poles shoved into the snow that were bordering the roadway. People climbed up the small peaks and glided down them — no ski lifts here.

We also made a short 15-minute stop to see Barbary macaque (also known as Barbary apes), which are native to the forests of Arzou and most present in the wintertime. The town of Arzou itself is far more quaint — and lively — than the affluent Ifrane.

Within a few hours we had left the snow-capped mountains and ice-cold winds and were surrounded by the mud-and-hay architecture of Medelt, a border town between the Mid-Atlas Mountains and the Sahara desert.

Sadly, we only spent the night in this breathtaking place – the hotel included. For the first time since being in Morocco, I reveled in a hot, relaxing 25-minute shower — something I take for granted at home.

The next morning we hopped back on the bus and trekked toward Rissani, a small town of stone and sand where we stopped for lunch. After some bargaining for rings in the eclectic souk and picture-taking in the vegetable market, we grabbed our backpacks and met our drivers — it was time to take the Landrovers across the sandy dunes to meet the camels that would take us to our hotel for the night.

0 notes

Text

Scrub-a-dub-dub in the public tub

Checklist: large bucket, small bucket, luffa, savon noir, bar soap, shampoo & conditioner, flip-flops, towel.

As we walked down the medina streets with our bath gear, my little sisters and I paid our 10 dh to enter the nearby hammam – the public baths where Moroccans go (at least) once per week.

The only relatable yet still incomparable experience is going to the YMCA and showering, sweating in the sauna and de-stressing in the steam room after hours of swimming in buckets of chlorine-saturated pool water.

Still, the hammam is different. While I can’t speak for the male baths, the female ones were yet another cultural shock experience for me. Within seconds upon entering, my sisters had me completely stripped down to only my panties.

Covering my chest with my right arm and carrying my bathing goods in the other, we entered through a large metal door that opened into a steam room. Faucets spurt out piping hot water, buckets made small waterfalls that splashed across the tile and women were congregated in sections with sisters, mothers and friends — completely naked.

For the next two hours, we filled up buckets, lathered on muddy mask-like body soap, scrubbed off layers of dead skin and washed over and over again. While this was the longest bath I’ve ever had, it was also the most spa-like and communal. Women who I did not even know were willing to come over and scrub my back or refill my water buckets.

Bathing in Morocco is almost the complete opposite from the U.S., largely because of the drastic difference in the perception of personal space. Most Moroccans don’t bathe at home, many only visit the hammam. Thus, the only cleansing experience they have ever had or known is with their families and friends. Once again, I had to shed my personal conception of privacy and personal space to participate in a very normal experience for my Moroccan family and community.

9 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Le weekend à Salé

This past weekend, I ventured with my host family to Salé — a short five-minute cab ride across the schwia (little) river between the neighboring city and Rabat.

Here, we visited la grande maison, as Mama calls it, for the celebration of mawlidu n-nabiyyi (The Prophet's Birthday). The two-story house is home to grandma and two of the uncle’s families: one on top, one on the bottom floor. It even rests atop a café owned by one of the uncles and has a terrace that overlooks Salé and onto Rabat.

While traditional sallas (guest rooms) are decorated with beautiful Moroccan pillows, vases, porcelain and rugs, the beet naz (bedrooms) — at least six of them — look like any other Western teenager’s room: desktop computers, speakers, stacks of old books and sports paraphernalia among disheveled closets full of an array of stylish wardrobes — leather is in high-fashion for many Moroccans.

Spending time with my two little sisters in our petite maison in the medina has been great, but it was wonderful to explore the homes, streets and sights of Salé — not to mention hang out with Moroccans my own age.

Zayneb and Safae have three cousins in their early twenties, all college students, too. Since gender dynamics and norms are still a bit tricky to discern here — especially whether co-ed “friendships” truly exist and, if so, how they manifest in Morocco — I broke the ice with the guys through musika.

Once Backstreet Boys came blasting through the stereo speakers of the nearby computer, childhood memories flooded my thoughts and roused a bit of laughter within me. Immediately, I asked the boys about various pop artists and rock bands Moroccans listen and dance to. No sooner did the conversation veer in a direction typical of any group of college students: nightlife, dancing and parties — all en francais, of course.

In celebration of the Prophet’s birthday, Salé hosted a dorshumeh (parade). Here, Berber tribes and other religious figures from across the country came to march, playing ethnic music and displaying their traditional and tribal garments. The streets were packed with people, and little boys and girls gazed in awe from the road’s edge or from atop the adobe walls. It was incredible to hear the different sounds and see the many colors and peoples of this country express their culture through performance.

The following day, I went with two of the cousins to see the beach. Salé bodes a bit larger, though far dirtier, sandy coast than Rabat. The waves crash along the rock jetties and look onto the Atlantic from one side, while the other is calm and merges into the small, salty river leading back to Rabat.

Despite a short two days and nights in Salé, I discovered a new location for some good shopping, great running routes and breeding grounds for newfound local friendships.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Ma famille

After a long week of orientation, I finally moved in with my homestay family.

While students waited on one side of the CCCL with luggage in hand and the families on the other, our homestay coordinator began playing matchmaker wit her list of names. As my eyes danced around the room, I caught those a little one, Safae (who is 6 years old), who spotted me in the crowed. No sooner was a greeted with a hug and two darling pecks on the cheek.

Mama, Zayneb [Zee-neb] and Safae [Sa-fa] all embraced me with open arms and two pecks on the cheek — the Moroccan greeting. Instantly, my nerves washed away and I felt an immediate sense of belonging to this family.

Safae was so excited to see me and have a new “big sister” in the house. She only speaks Darija (the Moroccan Arabic dialect), so we communicate and connect in some of the most basic human ways. At first, facial expressions and body movements guided us. Zayneb, who is the most mature 14-year-old I have ever met, later assumed the role of translator: telling me what Safae says — in French, of course, because the family doesn’t speak English.

As a result, my French — which I eagerly put on the backburner after finishing the AP exam in high school — is improving with each sentence I (attempt to) formulate. As a communications major, it’s ironic how one of my biggest challenges this semester will be learning how to communicate in my daily life while living in Rabat.

When I arrived, Baba (father) greeted me at the door with a Salaam and showed me around the petite maison, as Mama calls it. Upon entering the house and ascending the stairs, a sink greets you at the top and the door to the bathroom is just ahead. Across the way is a little kitchen. In Morocco, this is considered the “woman’s place” because, normally, she alone does all the cooking for the family. Traditionally, it is also where women talk to their female neighbors or family members without having men listen in on their conversations. This is but one of the many gender dynamics and norms here.

The apartment-like home also has a living room equipped with couches lining the walls entirely, stopping only at the entrance. At meal times, the room transforms into the dining room; simply add a table and tablecloth. When it’s time for bed, the room yet again transforms into beds for Zayneb and me. Multi-purposing seems to be at the core of everything here — which is a highly sustainable and less wasteful, in my view.

Since the family lives in the old medina, I get to experience everything in the utmost traditional sense — almost. Aside from a Western toilet, our house has a gas tank just outside the bathroom, which is used to generate hot water for the faucet. This is especially useful when it comes time to shower: hot water, large bucket, small bucket — Ca y’est.

This is another Moroccan way of living; it’s not just those in the medina. Once a week, everyone goes to the hammam, which is a large public shower (one entrance for boys, one entrance for girls). The hour-long ritual consists of lots of intense scrubbing (like exfoliation), rinsing in incredibly hot and soothing water, then sitting in a steam room. The experience is like going to a spa-like YMCA — or so I’ve heard. I haven’t gone yet, but I’m looking forward to embracing this new experience. Once again, I will have to renegotiate my sense of “privacy” — which is almost an inconceivable concept to many Moroccans unfamiliar with Western norms —because everyone showers naked in this open public space, even in font of strangers…

Each second I spend with this family, I grow more comfortable with these foreign cultural concepts, customs and norms. The moment I entered the house I was treated like a family member, not a visitor — aside from meal times. The constant repetition of “Megan, kuli kuli” or “mangez mangez” (“eat, eat”) won’t let up until I take another bite — and then maybe one more. I have a feeling that my pants may not like me for this at the end of my 4-month stay here.

Despite our cross-cultural differences, there are far more intercultural similarities that span across the human race. The first evening consisted of picture-showing, home video watching and dancing — even to some Shakira. After a week of being here, I’ve discovered that if I look for these similarities — rather than the differences — I become more flexible, open-minded and comforted by the notion I’m surrounded by kind and loving people. They just happen to come from a different place.

0 notes