Text

Myanmar Entry for ArtAsiaPacific Almanac 2020

[featured in ArtAsiaPacific]

By Min Pyae Sone - January, 2020

As Myanmar gears up for its general elections, slated for 2020, the nation faces numerous, bubbling conflicts. In 2019, the Tatmadaw army escalated its offensive against Rohingya and Arakan insurgents in Rakhine state. Myanmar also stood trial at the United Nations International Court of Justice in December for charges of genocide against the Rohingya people.

Despite political instabilities, the artistic expressions of Myanmar’s artists and curators are increasingly dynamic. The local arts infrastructure is supported by commercial galleries working with artists, with very little input from Myanmar’s Ministry of Religious Affairs and Culture. Organizations such as the Japan Foundation, Goethe-Institut, and the American Center offer funding for select exhibitions that suit their remits. However, shows are still commonly financed by artists themselves.

Among government-run platforms in Yangon, the National Museum of Myanmar’s sparse programming included the “Contemporary-17 Art Exhibition” (1/12–18) of all male artists.

With few private patrons to count on, arts practitioners continued to collaborate with foreign organizations in 2019. Curators Sai Htin Linn Htet and Ushmita Sahu worked with the United States nonprofit Emergent Art Space to present “Building Bridges Yangon: New Media Art Exhibition” (7/19–30) as part of the local initiative My Yangon My Home – Yangon Art and Heritage Festival. Spotlighting works by over 20 emerging artists from Myanmar and abroad, the show inaugurated the restored Old Tourist Burma Building. Later, exiled Shan artist Sawangwongse Yawnghwe declined to take part in the European Union-funded exhibition “Everyday Justice” (11/16–29) at the Old Tourist Burma Building, due to concerns over the EU’s stance toward Myanmar’s current affairs.

Pyinsa Rasa, a collective dedicated to arts development in Yangon, presented a project at another revamped colonial landmark, The Secretariat. The group exhibition “Sa Gar Ahla Ku Htone” (11/2–17) tackled internet culture with photography by Hkun Lat and works by performance artist Thadi Htar, among others. New Zero Art Space continued to support emerging artists through exhibitions.

A part of the Pyinsa Rasa group, Myanm/art gallery opened a new space in downtown Yangon, on 48th Street, and launched “God Complex” (5/18–6/12), spotlighting street-art-inspired canvases by Kyaw Moe Khine, also known as Bart Was Not Here. Kaung Su’s “Ashes of Time” (9/7–27) touched on historical genocides. Other commercial ventures in Yangon include the River Gallery, where Htein Lin’s solo show “Skirting the Issue” (5/11–19) included controversial displays—canvases made from women’s skirts, which traditionally are handled by women only. Lokanat Galleries held a memorial exhibition for the late experimentalist Phyoe Kyi, curated by artist-couple Tun Win Aung and Wah Nu (7/12–15). A new addition to the gallery scene was Kalasa Art Space, which kicked off its first year with big names, such as septuagenarian painter Aung Myint, who had the solo exhibition “17 A.M” (10/5–16). Nawaday Tharlar Gallery presented Kaung Kyaw Khine’s renderings of blank-faced civilians (7/13–19), evoking the frustration of locals who have been anticipating political changes.

In the contemporary photography realm, library, workspace, and gallery Myanmar Deitta had two noteworthy exhibitions: “Bridging the Naf” (6/25–8/18), by the all-female Thuma Collective and the Bangladeshi Kaali Collective, and “Disclosure” (9/28–10/20), featuring Thuma Collective. Both shows were preoccupied with issues of identity.

In June, Dawei Art Space opened its doors in the southeastern city of Dawei, surviving a harsh monsoon that hit the area. An ode to the region’s coastline, “Sea Lovers” (10/12–14) was organized by native Tavoyan artists.

Myanmar artists participated in several international exhibitions. Min Thein Sung’s dust-covered canvases were showcased at the 2019 Singapore Biennale (11/22–3/22/20). Installations by Moe Satt and Nge Lay tackling various aspects of Myanmar’s history were at Biennale Jogja XV (10/20–11/30). Moe Satt also performed at Asia Contemporary Art Week Field Meeting (1/25–26) in Dubai, and presented projects at the survey “Polyphony: Southeast Asia” (11/9–12/20) at Nanjing University of the Arts, alongside ceramist Soe Yu Nwe, who was in residence at North Seattle College.

Looking ahead to 2020, Myanm/art will present exhibitions featuring Richie Htet and Soe Yu Nwe.

0 notes

Text

Controversial Myanmar pastor who claimed Christians are immune from coronavirus tests positive

[featured in Myanmar Mix]

By Min Pyae Sone - April 14, 2020

Myanmar pastor David Lah told online viewers of his service that devout Christians would be immune to coronavirus before testing positive for the virus himself.

At least five Covid-19 cases have been traced to his religious service at a church in Insein township on April 6, among them rock band Iron Cross singer Myo Gyi, 44, who regularly sings hymns and Christian rock with the pastor.

An estimated 100 people are thought to have come into contact with those who attended the service, an official told news agency Anadolu Agency.

A health official confirmed to the agency that the pastor is among the new cases.

The gathering defied government instructions to avoid mass gatherings, an order echoed by the Myanmar Council of Churches in a Facebook post on April 2.

But Lah is no stranger to controversy. He has made anti-Muslim and anti-LGBTQ statements in his sermons as well as claims that Christianity somehow protects worshippers from the pathogen.

“I can guarantee, if you are walking the true path, and have the whole of Christ in your heart, you will not get the disease," Lah told his followers.

A churchgoer familiar with Lah who asked for anonymity confirmed his diagnosis to Myanmar Mix. On hearing of the spread of Covid-19 at Lah’s service, the worshipper text the pastor his best wishes and said he received the reply: “Yes, amen.”

Myanmar confirmed 21 Covid-19 cases yesterday—the highest daily jump, bringing the number of cases to 62 and four deaths. The government has urged people to stay at home over the typically riotous new year period as Myanmar has seen a gradual uptick in the number of locally transmitted cases.

Myo Gyi, his wife, elder sister, and two children, who live in Bahan township’s Pearl Condo, were quarantined in a government facility in Hlaing township on April 12, while authorities imposed a total lockdown on the building where the family lives, reported Myanmar Times.

Meanwhile, government spokesperson Zaw Htay told BBC Burmese that vice president Henry Van Thio, a Christian from Chin state, will be tested for the virus after photographs circulated on social media showing him with Lah.

Zaw Htay said the photos were taken on February 9—the same day Lah spoke at the Myanmar National Youth Conference in Naypyidaw—and the earliest confirmed infection in Myanmar was on March 23.

However, he said the politician and his family members could see the growing public concern over the news, and so Henry Van Thio along with more than 30 other people would be tested.

Lah’s Facebook page describes him as a Myanmar-born pastor residing in Toronto, Canada and currently “touring around the globe to preach the gospel.”

Since February he has preached in cities including Mandalay, Yangon, and Naypyidaw.

During one church service, he is filmed saying the number 768—which some people believe signifies praise to Allah—adds up to 21, meaning “the world must become a Muslim world in the 21st Century.”

He goes on to espouse trite but also sometimes bizarre anti-Muslim conspiracies, which are reminiscent of inflammatory rhetoric heard from ultra-nationalists in Myanmar.

“In cities like London, they are spreading their faith just with sheer population numbers,” said Lah. "When their kids finish the 12th grade, they force them to become lawyers. They are trying to influence the government and the law.”

Perhaps most strangely, he refers to the Panthay, a predominately Muslim Hui people of China who migrated to Burma in the 1800s.

"A Chinese man is frying noodles in peace, a Muslim leader will ask him 'do you want Allah or death,' so the Chinese man shouts 'Allah Allah Allah!' so he is now Panthay,” said Lah.

In another clip, Lah targets gay men, who are sometimes labelled the derogatory term "a chauk" in Myanmar, which is also the same word for "dry."

"There's a reason why we called homosexuals a chauk, because they are dry," said Lah. "For them to become wet again, they need Christ."

0 notes

Text

Where are the curators in Myanmar’s art scene?

[featured in Frontier Myanmar ]

By Min Pyae Sone , Photos by Thuya Zaw - February 9, 2020

The development of contemporary art in Myanmar has been hampered by a paucity of curators, with most galleries asking artists to arrange, fund and promote their own exhibitions.

Arts reporters in Yangon have plenty of artists and gallery owners to interview, but one art world actor seems to always be missing.

Myanmar has been short on curators since the arts scene began a revival of sorts about 20 years ago. The word “curator” lacks a direct Burmese translation, and the role itself is little understood in Myanmar. Though attitudes are changing, the government and much of the public tends to view contemporary art as a novelty, with little precedent in Myanmar culture, and as an amateur passion where professional curatorship isn’t required.

Those wishing to become curators – or to work with galleries exercising a degree of curatorship – have few options. The national universities of art and culture in Yangon and Mandalay offer a degree in “Painting” that asks students to memorise only a few select details of global art history while focusing on painting techniques.

Ko Aung Khant Kyaw, 23, who graduated from NUAC Yangon three years ago with a bachelor’s degree in Painting and teaches Visual Arts at SKT (formerly Horizon) International School, participated in a group discussion at a workshop on curating hosted by the Japan Foundation last November in Yangon, which I attended. “I’ve been in many group exhibitions, but I have yet to participate in something I’m proud of,” he said, attracting agreement from the assembled artists and gallery managers..

After the event, Aung Khant told me about the exhibitions held at NUAC for graduating students. “There were no curators there, just students, parents, and other relatives,” he said. “Exhibitions in Myanmar are just for socialising; people come to drink, talk and enjoy themselves. Nobody even looks at the art anymore.”

Government patronage of the arts, such that it exists, has done little to raise standards or increase public appreciation of contemporary art. In the 2018-2019 fiscal year, the government allocated more than K35 billion (US$24 million) to the Ministry of Religious Affairs and Culture.

Though most of this was spent on religious monuments and ceremonies throughout the country, the ministry is also responsible for funding the national universities of arts and culture and the National Museum in Yangon. However, the museum asks artists to donate works to its staid permanent display of contemporary art and curates just a handful of events each year, mostly about history and traditional culture.

With little help from the government, the contemporary arts milieu relies almost entirely on commercial galleries. Many of the owners of these galleries, who struggle to even pay the rent, see a curator as a luxury they cannot afford. Instead, they hand their spaces over to artists, or artist groups, to supply and display the artwork as they see fit, charging them rent and taking a cut of sales, and often leaving artists to do most of the promotion.

“We let the artists do what they want and do not interfere in any way; they are the ones who pay for our space,” said one downtown Yangon gallery owner, who asked me to leave when asked if I could interview him and record his name. “No hard feelings, but you really should be asking bigger galleries, not me,” he said as I reached the door.

However, a small number of talented curators in Myanmar have been behind a number of high-concept exhibitions in Yangon in recent years, which have taken place in large public venues like the Secretariat building rather than conventional art galleries. This rise in curatorial practice has been encouraged, directly and indirectly, by grants and funding from foreign cultural organisations in Myanmar.

Sai Htin Linn Htet, 28, is a Yangon-based curator, multimedia artist and human rights activist whose work addresses the themes of empathy, pollution, gender equality, identity and discrimination. He is also programme manager of the biennial My Yangon My Home: Yangon Art & Heritage Festival and co-curated the July 2019 edition, called “Building Bridges Yangon”, with Indian curator Ms Ushmita Sahu at the newly renovated, colonial era Tourist Burma Building opposite the Sule Pagoda.

Helped by a team of volunteers, Htin Linn Htet was responsible for curating many of the Myanmar artworks featured in the international exhibition. In an email interview, he described the challenge of developing an exhibition design “that is suitable to the venue” while also providing room for “the voice of the artists”.

Htin Linn Htet, who has now worked with several foreign curators, sees it as his role to advise them on the tastes, values and sensitivities of the Myanmar public, making space for stimulating foreign subjects and styles while making sure local culture is represented.

However, despite frequently conservative and dismissive attitudes from the public towards contemporary art, he insists that “things are rapidly changing here”.

“We are going no way but up,” he said. “I’ll continue to promote emerging artists, stepping between their artworks and the public, as a mediator, curator, and a friend, as long as there is a need for one to materialise their unrealised projects.”

Yet, Htin Linn Htet says the dividing line between professionalism and amateurism in Myanmar art remains thin. Artists, who have to depend largely on self-promotion, have little recourse to feedback or guidance from galleries and other institutions. However, River Gallery, which opened in downtown Yangon in 2006, bucks this norm.

“Rather than telling the artists what to do, we focus on helping the artists articulate the 'story' behind the artwork if they need assistance on that,” said River Gallery owner Ms Gill Pattison, a New Zealander who has been living in Yangon since 2002. “The language of art does not always readily translate into regular language, and sometimes we can help the artists find a way of conveying more of their thoughts and feelings about their works.”

Pattison and River Gallery work with some of the most internationally recognised Myanmar artists – most of whom have experience working with overseas curators and sometimes curate their own shows. Pattison said that when she was planning to open River Gallery in 2005 as a professionally curated gallery in the international mould, “I really didn't have much idea of whether it would be successful, whether anyone would visit, or whether anyone would buy.”

However, it helped that she knew many talented artists. In 2004, Pattison had organised the now defunct Myanmar Contemporary Art Awards in cooperation with Myanmar Times. “The artists entrusted me with their works at the outset, and then I think we repaid this trust through professional, transparent business practices and we did our best to promote their careers,” Pattison said.

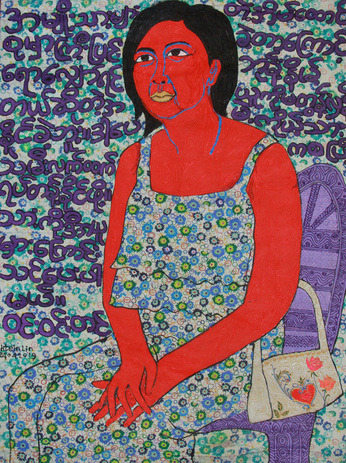

An artist often featured at River Gallery is U Htein Lin, 53, a star in Myanmar’s contemporary scene, who has a satirical and sometimes controversial approach to social and political issues. His “Skirting the Issue” exhibition at River Gallery last year tackled misogynist taboos by featuring canvases made from htamein (a women’s longyi), which are traditionally seen as polluting for men and are handled only by women.

When I interviewed Htein Lin at a Yangon teashop late one evening in early January, he began on the subject of curatorship by talking about his six-and-a-half years as a political prisoner.

“In prison, I painted and even organised a solo show there for the prisoners. I suppose you can call it my first time curating,” he said. It was a risky venture because organising such an event in prison was prohibited.

“Dealing with the guards and prisoners for space and logistics was very hard,” he said. “First of all, it isn’t an art gallery, it’s a prison. Second, there’s the problem with the timeframe and finding the opportunity. Third, how we would invite people to my show.”

Htein Lin hand-drew the invitations on used snack packets and distributed them around the prison, a task made easier by the fact that inmates in each block of 15 cells had to change cells every day. “We asked a single-cell inmate to let us use his cell when everyone was getting ready to switch cells. The cell was nine feet by nine feet,” he said.

Htein Lin and some fellow inmates had to negotiate with the guards and arrange times when occupants of the 15 cells could view the works, which were displayed on torn plastic bags attached to the walls with toothpaste. When the day finally came, inmates showered, dressed up and visited the cell to view Htein Lin’s works.

Soon after Htein Lin’s release in 2005, one of his close friends, fellow artist Daw Chaw Ei Thein, curated and displayed a selection of the hundreds of works he created in prison. The exhibition at her house in northern Yangon, near the airport, ran for only one day because it attracted the attention of plainclothes intelligence officers.

When he returned to Yangon in 2013 after living in Britain for seven years, he started to curate exhibitions using ideas and curatorial principles gleaned from galleries in London, Paris and elsewhere. “A proper exhibition should make you feel and think differently about the things you saw after you leave,” he said. “That’s the curator doing their job.”

0 notes

Text

Beyond gallery walls: Yangon’s graffiti artists

[featured in Frontier Myanmar ]

By Min Pyae Sone , Photos by Nyein Su Wai Kyaw Soe- October 26, 2019

Graffiti flourished in Yangon a decade ago, but the number of artists has since slumped by more than half, and some say the scene never developed its own style.

Graffiti is synonymous with delinquency in most countries, and Myanmar is no exception. Many Myanmar parents would regard a young person going out at night to deface walls and buildings as no more than a deviant. However, for the past decade, the graffiti scene in Yangon has allowed a small group of young people to defy conservative norms and stake a claim on the city’s streets.

With the international art world’s embrace of artists like Keith Haring, Taki 183 and Blek le Rat, graffiti has come to be recognised as something much more than a crime or gesture of defiance. That is, art that reaches beyond the walls of a gallery.

We easily disregard the lurid doodles and scarcely legible text sprayed in alleys and on fences around abandoned construction sites in Yangon, but those who care to delve into the scene will find a small but diverse group of professional and amateur artists, most of whom are still drawn to the raw, vandalistic approaches of the New York graffiti movement.

However, since the city’s graffiti scene began to blossom a decade ago, it has yet to develop a discernable style of its own. For most practitioners, graffiti has been a way to plug into a cool, foreign culture, and this has created a tendency towards imitation rather than innovation – similar to pop music, where cover songs rule, and a large portion of the films produced in Myanmar.

Like Yangon’s hip hop scene, many of Yangon’s graffiti artists are from fairly well-off families. Some picked up an appreciation for graffiti while studying abroad, and this has given it an added “elite” allure for aspirational young people. The graffiti scene’s connection to politics, and any genuinely dissident sub-culture, has been oblique at best, and few graffiti artists describe themselves as “political”.

But to dismiss Yangon graffiti for these reasons is to forget that it came of age at a time when embracing an item of foreign culture such as graffiti was to defy state policy.

Hip hop’s twin

In the late 2000s, many young people were intrigued by the sight of barely decipherable scrawls that popped out of stale walls or columns left mouldy by years of neglect. Graffiti culture emerged in Yangon at a time of isolation, when limited access to the internet and an official censorship regime concerned with protecting traditional Myanmar morals kept “deviant” Western cultural influences at bay.

Before that time, ACID, one of Myanmar’s first “underground” hip hop groups, who performed in small, unofficial venues and sold most of their recordings illegally, introduced elements of predominantly American hip hop culture to a young and impressionable fan base in the early 2000s. It was only natural that graffiti, together with baggy jean shorts and oversized T-shirts, appeared along with ACID’s raunchy music videos and live shows.

After ACID’s demise in 2008, when two of their members were arrested for assisting the pro-democracy movement – an unusual fate for Myanmar rappers – graffiti culture in Yangon mostly thrived underground, though it received some assistance from the French and German cultural institutes.

Ko Thu Myat, 33 who has been doing graffiti since 2008 and now works mainly on canvas, believes the scene’s development has suffered from not being moored in a broader and more radical sub-culture, which makes it feel a bit like a cultural transplant.

“There’s nothing special about Yangon graffiti, except the fact that it suddenly appeared. It’s almost like there’s a gap in our development,” he said. “Like technology; for example, we didn’t have any internet until recently. Now, we’re on our way to 5G. It’s the same with graffiti and street art in general.”

Thu Myat was among the fans captivated by late-90s American rap albums and decided to imitate the stylised lettering on album covers. He started with marker pens on A4 paper; it was a while before he was using spray cans. He learnt spray control and other techniques at an Alliance Française (now the Institut Français de Birmanie) workshop on graffiti in 2008. Thu Myat also tried his luck in the music industry, which he said “invoked his passion” for graffiti even more.

“Nobody really understood why they were tagging; it just all looked cool to us,” he added in an interview at his family home in Yangon. “It took us [the graffiti writers] a while to figure the fundamentals, the history of what we were doing. Then I was properly obsessed!”

Ko Toe Wai – better known as Satan – was a member of Western Crew, a small, rowdy gang whose members hailed from Sanchaung Township. (Nyein Su Wai Kyaw Soe | Frontier)

Drinking, fighting and spray-painting

The first official graffiti event in Yangon was held at the New Zero Art Space in Dagon Township in 2009. It enabled graffiti artists who were comfortable about revealing their identities to share their knowledge with curious young people. Many who attended that event are still doing graffiti today.

In 2012, weeks after graffiti artist Ko Arkar Kyaw made headlines for a mural welcoming the visit by United States President Barack Obama, the Yangon municipal government issued a warning against graffiti that threatened criminal penalties. Among those who ran foul of the law was a small, rowdy gang that called itself Western Crew because its members came from Sanchaung Township in western Yangon.

“It was originally a group for the members to meet up and get drunk, get into fights, you know… the usual,” said Western Crew’s Ko Toe Wai, 28, better known by his alias, Satan.

Initially, Toe Wai was strongly inspired by American bubble fonts. He began experimenting and worked odd jobs to support himself. His efforts have enabled him to become one of the most successful commissioned graffiti artists in Yangon.

In 2012, when the municipal government cracked down, Western Crew was busted. “It was kind of late,” Toe Wai recalled. “Me and a group of friends decided to go wild, you know, picking up boxes of ATM spray cans and going around tagging up alleyways.”

“After the deed was done, we noticed two men tailing us. We weren’t sure what to do and disregarded it. One by one, they picked us up at our houses. By the time they showed up at mine, a lot of people had already been caught. It was a pretty big thing; a lot of squad cars, motorcycles. It was chaos. When we finally got to the station, all the other [detainees] were cracking up because of us. They thought us being caught for drawing stuff on walls was hilarious!”

At this time, plainclothes intelligence officers on the lookout for political dissidents would tail graffiti artists. However, most police officers regarded graffiti as a petty offence that generally didn’t warrant charges. This didn’t preclude mistreatment, though. Officers would stake out locations preferred by graffiti artists and detain and beat them.

One favoured spot was on Lower Kyeemyindaing Road, provocatively close to Ahlone Township Police Station. With graffiti even appearing on the walls outside the police station, police action was never thorough, but officers would sometimes take graffiti artists into custody for short periods as a pre-emptive measure.

Into the gallery

Today, only a small group of artists are continuing the tradition. From the original community of 50, only about 20 remain, said Toe Wai, who believes a failure to innovate a distinctive style meant that the scene lacked staying power.

Toe Wai said improved internet access is a mixed blessing in this respect, because it allowed artists to more easily copy internationally renowned styles rather than develop their own. Although the Yangon municipal government tried to block a proposal for a public graffiti zone made in 2013, the idea went nowhere for other reasons, including differences among artists.

Some graffiti artists now exhibit in gallery spaces, and bring graffiti elements to canvasses and installations. They include Ko Kyaw Moe Khine, 23, aka Bart Was Not Here. Growing up in Yangon in the early 2000s, he regarded hip hop and graffiti as synonymous; but after getting a diploma from Singapore’s Lasalle College of the Arts in 2018, he developed a deeper appreciation for graffiti from the perspective of global art history.

“I thought if you like hip hop, you’d like graffiti,” Kyaw Moe Khine said, describing his initial attitude. “As I grew older, I started to see it as more of an art movement than just an element of hip hop. In my opinion, hip hop is more commercialised … there’s an industry for that. But when it comes to graffiti, you don’t make money off it.”

Many of Kyaw Moe Khine’s paintings include graffiti-style lettering but he tries to introduce not only graffiti’s motifs but also its spontaneity into his work. “I do the same thing I do on the walls, but on a canvas,” he said.

But he said a commitment to spontaneity shouldn’t preclude an appreciation of where graffiti came from and how it has influenced the rest of the art world. “Most graffiti writers don’t research art history,” he said, describing this as a mistake. “When you’re an artist, you need to acknowledge all the history behind the techniques we use today.”

0 notes

Text

How China taught me thanaka is not the next jade

[featured in Myanmar Mix]

By Min Pyae Sone - December 21, 2019

“Pay me 600 yuan and I’ll help you cross the border.”

I choose to stay in the long queue rather than accept this crook’s illicit offer.

Scammers abound at the White Elephant border gate between Muse in northern Shan state and Jiegao in southern China. They prey on rookie travellers who are deeply paranoid of all things China—I count myself among these. My only other experience with Chinese immigration was a bitter dispute with Guangzhou customs over some hand cream.

“You can’t bring luggage over there.”

I can. The reason why I am here is my luggage: seven large cardboard boxes of Myanmar’s favourite cosmetic, thanaka, a paste made from tree bark used as sun protection and makeup.

I want to share its wonders with the good people of Ruili in Yunnan. I want the Ruilians to buy it all, so I flash my seven-day border pass to customs, who, thankfully, spoke more Burmese than my limited “ni hao”” and “xie xie” Mandarin.

Myanmar nationals enjoy this 1,000-kyat (US$0.70) visa in the spirit of “pauk-phaw,” a fraternal bond between my compatriots and the Chinese that was clearly not recognised by the swindlers at the gate.

China has a big appetite for certain Myanmar exports—namely jade, an industry worth about $31 billion in 2014, nearly half of the country’s official GDP that year.

But the trade is mired in corruption, with untaxed profits reportedly flowing to armed groups and political elites, while the gemstone is mined under sometimes-deadly conditions in Kachin state.

Meanwhile, I can assure you reader, the Myanmar-China trade of thanaka is spotless and my luggage probably comprises most of it.

Within a few yards of passing through immigration, a wildly different way of life presents itself, a clean metropolis with shiny big buildings towering over crowded, dusty Muse across the river.

After passing a few road signs in Burmese—presumably placed for diplomatic courtesy—I reach my hotel (not the ‘love’ kind) and chat with the manager who also sells petrified wood, or as he described it, “tree fossil jade.”

“Myanmar,” he chirps, indicating the origin of an ancient slab of rich colours and patterns.

“Why is it in China?”

He shrugs sheepishly like a man living in a city with a flourishing black market.

Outside gem shops outnumber restaurants, and stylists dye the hair of middle-aged aunties in the biting cold. Ruili is weird; China is weird, time to sell some thanaka.

I arrive at a three-day exhibition held in a massive complex called Venus City of Stone and Culture, where young men and women brandish Xinxing cigarettes and scream prices into their phones as they fixate on live video of jade.

We set out our thanaka shack near a hanging skinned crocodile and begin explaining in broken-at-best Mandarin to a stream of Chinese customers who all sound like they’ve skipped breakfast.

Faced with three days of hard bargaining and thanaka not being jade, we managed to shift 20 mask and soap sets before returning to Myanmar with the same seven boxes.

After sampling Chinese beer and some local delicacies, I also brought home a cripplingly bad stomach. Jade will always be the apple in China’s eye, but at least I tried.

0 notes

Text

I stayed at a Bangkok love hotel with my parents for six nights

[featured in Myanmar Mix]

By Min Pyae Sone - November 21, 2019

Sunday, November 3. A day before my parents and I travelled from Yangon to Bangkok to sell Myanmar’s favourite cosmetic, thanaka, at a business exhibition. Our Agoda Homes booking was a beautiful, spacious booking that, once booked, was inexplicably declined by the owner.

In all its ‘trust me on this one’ wisdom, Agoda repeatedly recommended a self-identifying resort with “Madame” in its name. It should be known that I am not a bona fide traveller of Southeast Asia nor do I own a pair of elephant trousers. I am but a student blindly groping for wholesome lodgings, so there was absolutely no chance I would know where couples (or more) go for that kind of thing in Bangkok.

Boldly, and without any hesitation, I ignored the red flag screaming from the garish photographs and proceeded to book my mother, my father and myself in two rooms for what ultimately became six nights of snail massacres, mosquito bites and stiff bedding.

For our three-day stint of meandering around the exhibition hall, we had lugged all the cargo ourselves—50 kilogrammes of posters, vinyls, cosmetics, lights and string bags—wearing down your poor author’s prematurely painful lower back.

A whole day of standing surely deserves an evening spent relaxing at a luxurious hotel, right? Wrong! Not long after we arrived at Madame’s, we searched for the receptionist, only to see a small podium with A4 paper stuck on it that said, “Check-In.” As we knocked on various huts to find a receptionist, my uber-hygienic mother glanced at the coating of dust on the laminated sheet. The build-up of loathing had begun.

Following a name and sign here no-questions-asked check-in, we went on to explore our rooms, which, decorated with tacky wallpaper and chequered cushion walls, would be similar to sleeping in a KTV room. From the bathroom door, a poster of a woman’s rear winked back at me. It was as I anticipated, a love hotel.

What noises pierced the night? Sadistic Thai threats and whip cracks, you say? Well, dusk was actually dominated by an old grandmother who may well have been shouting at a wall.

The toilet was built on some flimsy drywall and shuddered at every flush. Disorientated, I would step out onto a battalion of snails and hear the crunch of shells and guts underneath my feet.

Other than the swarm of mosquitos, which I prayed had not taken an extensive tour of the premises before sucking my blood, and the night-out in Greenland air-con, it was a decent sleep for US$25 per night. Yes, the pillows stank of bleach, the beds were Thai-prison hard, and a fly floated helplessly in the electric kettle, but it could have been worse.

The following night our all-male housekeeping team forgot to clean my parents’ room. Near midnight, my father knocked on their hut, to find three sleepy men rubbing their eyes. They may well have been in this situation before—a late-night call from a randy guest—except my father’s fetish was for orderliness. He expressed that fetish in what I could only imagine was the most awkward prolonged reprimand of broken English.

Almost satiated on two complimentary spongy love cakes, I went to sleep that night with pangs of guilt for making my parents stay there. I would go see them, explain to them, but alas a cockroach scuttled from their room; I hate cockroaches and was forced to abandon the attempt.

The consensus, after all, was to take this family business trip for “new experiences,” before we learned we would stay at a pleasure-inn.

Yet I left a better man, a man of bolstered fortitude. I was worldlier than before, and I took a mental note that if, over the years, love remained elusive, I could always book myself in at Madame’s (without my parents).

0 notes

Text

How a ‘00s rapper became one of Myanmar’s favourite memes

[featured in Myanmar Mix]

By Min Pyae Sone - July 29, 2019

Mainstream Myanmar music in the early 2000s was soppy pop about young love and all that scheisse. Cometh the hour, cometh the man: Sai Sai Kham Leng, an inoffensive boy-next-door type who rapped his way into the hearts of teenagers across the country.

Something about his off-beat singing and slightly insipid music hit the right note and he soared to commercial success. His songs filled the hackneyed wasteland of the music industry back then; he has since become a household name, and for a few thousand kyats you can join his “Sai Stardom” fan club, whose motto, he has said, reflects the connection between him and his followers: “Sentimental Relationship.”

But more recently, 40-year-old Sai Sai, or Ba (Uncle) Sai, has become known for something else. An image of him with tears flowing down his perennially youthful cheeks has taken Myanmar’s Internet (Facebook) by storm.

The photo itself—a still from a film—is enough to elicit a giggle from me, although that has since evolved into a full-on chuckle fest.

To trace the memetic derivation of “Ba Sai,” we would have to go back to his role of a hopeless romantic in one of Myanmar’s very, uh, original, cinematic wonders, “Slaves of Cupid,” released in 2015.

In one pivotal scene, his character engages in a heated argument with his lover, played by award-winning actress Phway Phway, over the third side of their love triangle.

Ultimately, Ba Sai’s character ends up punching her while shouting “I fucking love you.” Cue dramatic guitar solo and a freeze frame of Ba Sai’s almost cartoonish figure staring through the doorway.

https://www.facebook.com/a93eefa5-8f25-4fdb-b04c-c69214af7290

Perhaps it’s the mixture of raw anger and regret painted on that handsome face, much like my own after getting whooped by my dear mother, but it is this moment that has captured the attention of the masses.

Since then, the sons and daughters of Yangon have photoshopped his thespian efforts with countless pictures; from kindergarteners to a young heavily-tattooed fellow handcuffed to a mug of what may well be herbal tea.

While the context of the meme does not matter much, the legend of “Ba Sai” was born and, just as his songs of yore had done, it found its way into the hearts of Yangonites—including mine.

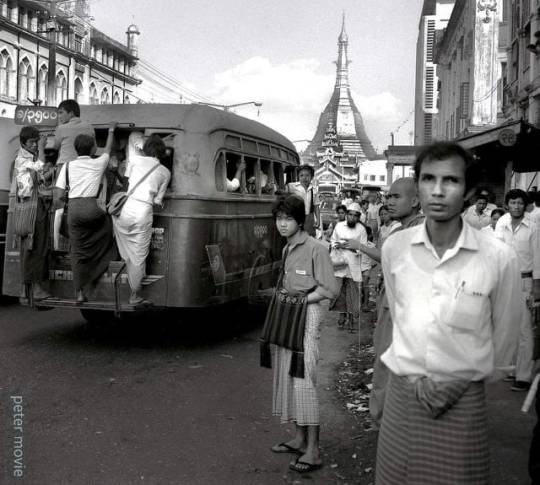

When you look at the image below, you might think it’s an oldish photo of downtown Yangon with Sule Pagoda in the background. Look again! Ba Sai is there, where you least expect him.

And now the singer is my generation’s “Where’s Waldo?”. A sorrowful face, crying amid the crowd, a noughties soft rap songwriter pleading to be found. But he is not our only meme star; stay tuned for more viral madness.

0 notes

Text

ဗလာအလွတ်(Ba Lah Ah Lut) – Fundamentals of Myanmar AbEx

[featured in Myanmore]

By Min Pyae Sone - September 1, 2019

An AbEx artist through and through, Soe Naing uses both oil and acrylic, to present ဗလာအလွတ် or “Nothing but Blank.” This exhibition is, as Soe Naing tells me, something he always wanted to do.

For Soe Naing, a painting isn’t complete until the viewer responds to it. As obvious as it is, a lot of people still asks him: “What does it mean?”

“ABSOLUTELY NOTHING!”

Soe Naing approaches the canvas with a blank mind – his ‘madness’ guides him through an unconditional way of painting bold stroke; most of which are so sombre, it dulls out the brightness of other brighter tones. A lattice-like layer that envelops and contains the bright burning hues underneath.

A work of his that deserves attention would be Nat Kadaw (a Nat’s wife). In it, an almost psychotic full-body portrait of Nat dancer – ambiguous in sex – strikes a pose. The body, true to the artist’s AbEx style, doesn’t have that much figure or anatomy. However, the face of the Nat Kadaw was full of emotion. Neither excited nor happy, it’s almost an even more melancholy alternative of some of Max Beckmann’s works – in subject matter, not style or technique. Colour-wise, Soe Naing has chosen to lay the background with countless layers of low viscosity dirty maroon that brings out the brighter Emerald green, which in turn helps the figure have some perspective and depth – even in a painting like this.

This is one of the very few semi-abstract pieces in today’s exhibition. When asked whether he prefers semi-abstract or just purely abstract, he simply said, “The semi-abstract pieces sell better.” In a country where the abstract or anything similar doesn’t attract buyers’ or just ‘simply don’t sell,’ Soe Naing finds it difficult to express the truest form of his art. Nevertheless, with the contemporary becoming more valued, things are bright for the future.

The exhibition lwas aunched today till the 7th of September at Lokanat Galleries. The artist is a very open and humble person, so a conversation is strongly recommended.

0 notes

Text

Speaking Through Layers: Guillaume D’Agaro

[One of my very first articles for Myanmore]

By Min Pyae Sone - September 1, 2019

Guillaume D’Agaro is a French mixed-medium visual artist, besides being an elementary school teacher at The French International School of Yangon.

“Energy and motion made visible – memories arrested in space,” a phrase from Pollock, describing his own work. We delve into an almost Freudian concept of our subconscious and how we can feel an attachment with a painting.

Guillaume is, in fact, very different compared to Pollock – both in style and aesthetic. Nevertheless, the phrase above compromises Guillaume’s motif and concept perfectly. He and Pollock have different backgrounds, like how the person writing this and the person reading this could have very little in common. How can we relate to one another, subconsciously, without prolonged conversations and tedious socializing? How can we have something we can share – aesthetically?

Born in Vannes and with an extensive background in academy art in Belgium and Slovakia, but never in France, he became fascinated by modern and contemporary art more than classical. The Belgium artistic educational system was perfect for him as it encouraged him to perform mixed media and installations.

“I was more sensitive to the aesthetic of things. We had one or two classes of Intro to Philosophy and it just really fits me,” he says with a cheerful smile.

Moving to Egypt and then to Myanmar was a transitional period for Guillaume’s snowball of artistic capability as it can be seen in most of his works, which are layered, something he tells me, “takes ages to dry.” A layer of both acrylic and oil paint a day for countless layers seems to be a very mentally tiring process. His works are layered because, in fact, his creation, his thoughts, and his experiences throughout his life are, in a sense, also layered.

Guillaume’s solo exhibition “Post-it” at Pansuriya will be exploring the concept of memories and have different types of people coming in and questioning themselves. “If I affected, at least one or two people with my art, I’ll be happy and feel as if I’ve done my duty.” The confusion between what we have in common and the differences, that is what Guillaume is trying to explain, embrace and portray.

In one of his paintings, “Reminiscence 1,” a cacophonous mixture of very bright pink, mellow bluish-green, and a tangy orange bloom is “suspended” upon a whitewashed canvas. To reminisce, looking back to a more nostalgic time; reminded by times of serenity and pleasure while being grounded by the harsh metallic matte black layered on top. Maybe this is a distorted scene of something you’ve seen before but never really gotten to remember?

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Birth and Death of Civilization: Kaung Su

[One of my very first articles for Myanmore]

By Min Pyae Sone - August 21, 2019

In about 3200 BC, the two earliest civilizations developed in the region where southwest Asia joins northeast Africa. From that point onwards, establishments have existed and many have fallen. This is only one of the many subjects that experimental artist Kaung Su explores with a sense of concealed radicalism. Min Pyae Sone meets him at his studio to talk about his motif and outlook for ‘the bigger picture’.

What Kaung Su calls the ‘Genesis’ of humanity began when human beings started to grow crops. The process of agriculture marks the start and the beginning of growth in civilization. From Mesopotamia to the Roman Empire, every one of these great civilizations began with a settlement in which fertile land and a body of water played a role; but a select few have withstood the test of time. Why? Kaung Su’s latest exhibition explains, questions, and portrays this topic.

“It’s more of a look into both the past and the future; a ‘warning,’ than a statement,” he says, going for the intricate cycle of over-ambitiousness that human beings have utilized over and over again in the past.

The Tower of Babel, may it be myth or reality, was the topic of the discussion. It can sometimes be ambiguous, but it represented the epitome of human over-ambition; in exchange, the people of Babel and their civilization were disbanded.

”My works are containers loaded with depictions of the celestial hierarchy, a history of mankind, and a devastated environment. At the same time, they are tied to distant cosmic history and have multiple meanings. The depth image of the impact crater refers to the fate of humankind and the randomness of evolution. I am trying to recreate a memory of cosmic catastrophe.”

In his mixed-medium (all sorts of materials or mediums) heavy canvases, most of which he implements less oil or acrylic paint, Kaung Su uses animal bones. The reason is understandable; the animal bones that are ground up and smear across huge canvases are to indicate “fossilization.” Everyone will eventually become fossils, and this is how Kaung Su expresses it.

Kaung Su is the first neon light artist in Myanmar and a conceptual artist by nature. His style is very expressive, free, and to be frank, ‘mature.’ In a world where the amount of time for an issue to go viral and become stale is very very short, it isn’t very wise to base your entire motif on it. According to Kaung Su, the maturity of an artist is a key factor in the overall quality of the artist and how they perform.

In his neon light set-up, “Earth’s Pay,” featured in his solo exhibition Infinity Rising, Kaung Su tells us these works are, and his own words: “[a] celebration of our outrageous fortune in existing at all.”

Kaung Su has participated and has been featured in many exhibitions. He has an upcoming exhibition, in September, on the topic discussed in this article. Follow the Myanm/art page on Facebook to stay up-to-date with his latest works.

0 notes

Text

A mother-son tale: Phyoe Kyi’s memorial

[One of my very first articles for Myanmore]

By Min Pyae Sone - July 14, 2019

Our relationship, connection, and conversations with our mothers can be rather extraordinary and is a rather unique topic to examine. This may or not be exactly the point the artist is trying to prove but it’s what I take in from the Memorial Exhibition at Lokanat Galleries down in Pansodan.

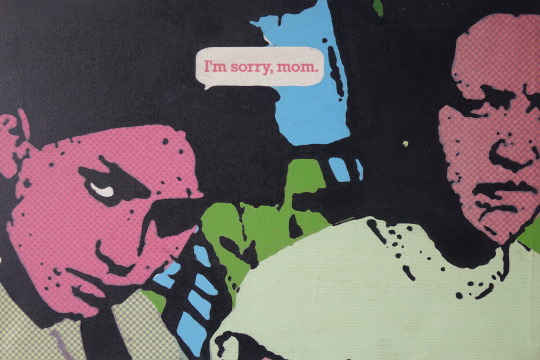

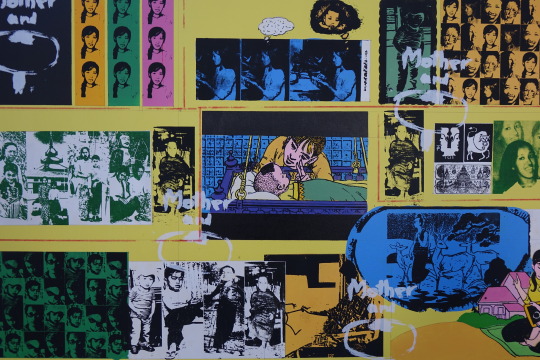

Phyoe Kyi (1977-2018) is a graphic designer, screen-printer, installation and performance artist based in Taunggyi. Before his untimely demise, he was involved in and led many exhibitions from 1996 to 2017 both locally and internationally. He experimented with different styles of painting from silkscreen printing to using acrylic paint on either Shan paper or canvas. A pop artist by style and technique but not by theme, Phyoe expressed his ‘bittersweet’ relationship with his mother—a rather intimate theme that isn’t normally categorized together with the ‘textbook’ norm of Pop Art that involves around the culture, society or even consumerism.

His triptychs and diptychs may revolve on mostly silkscreen prints of both new and old pictures of his family—which was just him and his mother—I couldn’t help but relate to the deeper meaning behind the concept of a maternal relationship. Being an artist may not be the ideal job for many Myanmar mothers, with many worrying about their child’s future and wellbeing—sometimes this can develop into something more stern. For Phyoe Kyi, however, this limbo of a mother worrying and a son revolting or even choosing a risky path became the focal point of many of his works.

A piece worthy of analysis would be Mother and Son #4, 2017. A triptych with a basic color scheme using both silkscreen printing and acrylic paint on canvas. It’s not the color scheme that grabs my attention but the story that is told.

A three-part story on the most important stages of his life, early childhood, late childhood, and later adulthood. There was almost no narrative in the first part, with different pictures of a happy family and a much younger picture of his mother.

The second, however, told a different story: a story of a mother who’ve accepted the fact her son is doing honest work with good intentions. In a letter from his mother, also printed on the canvas, it says: “Although we may not be rich, I want us to be pure and innocent in the long term.”

The third part is similar to the second, but with his mother fully content with the fact that her son is an artist.

To the regular visitor, Phyoe Kyi’s works may resemble a comic book and without his presence, it would seem hard to grasp his true intentions. It is saddening and nostalgic, maybe it might just be me, but Phyoe Kyi was a very talented person. This show is organized by his close friends and will go on till the 15th. Don’t miss it!

0 notes

Text

Kyar Pauk’s MICRO: Mainstream Punk Rock to Pretentious Art Flop

[One of my very first articles for Myanmore]

By Min Pyae Sone - July 6, 2019

In my opinion, art is made so that humans can openly express themselves or portray feelings of anguish, despair, joy, sadness, or even plain crazy through a story, poem, or a painting. It feels like punk singer Kyar Pauk (Han Htue Lwin), a member of Big Bag band, in his latest exhibition MICRO was nowhere close.

While most of his works are an adequate amount of expensive acrylic paint splattered on thick high-quality canvases, it certainly does not make up for his lack of originality. Grabbing a song from your favorite playlist and linking a QR code to it doesn’t add value. Especially if you’re setting the price at $1000 apiece.

This series is targeted toward the youth of Yangon, who are largely inexperienced in the topic of ‘art’ or even ‘expression.’ There was no general theme, just a collection of what he has painted over the past year or so. The title MICRO and its description describes very little of what the exhibition was really about. There was no logical explanation, nor were the paintings carefully explained. There was a slight “I don’t care what you think” vibe going on.

A good example to dissect would be Red, a painting that is clearly blue. The artist can name it however he likes, but it is a fact that this painting can be categorized in Rothko’s color field series inspired by European modernism and closely related to abstract expressionism while being a totally different genre of its own. This isn’t contemporary to me, this has all been done before. Blue swirls by a big paintbrush, with the occasional bristle being left inside the painting. Intended or not, it doesn’t look pleasing.

The artist already has a die-hard fan base for his art, synonymously for his music as well. It does, however, feel very experimental for him to try all of them—keeping in mind that he already has a book. This is his second exhibition, with his first exhibition being a semi-success.

It really is an open interpretation, anybody can see it as how they see it. For me, personally, these paintings make me feel bored and uninspired. The practice of uncoordinated or a lazy imagination does not make for good human expression. My worries are toward the young and inexperienced art lover who will look at this exhibition and grasp the wrong meaning of what ‘art’ really is. Art doesn’t need to be necessarily pretty, but it needs to make sense.

Disclaimer: These are my personal views, and your feedback—may it be good or bad—will be accepted wholeheartedly. I do not have anything against the artist nor will I ever. This review is done independently.

1 note

·

View note