Text

what’s wrong with this picture

Part I: A Walk in the (Upside-Down) Park

I’ve always wanted people to like me. As far back as I can remember, though, I was never convinced they did.

Don’t worry, I’ll spare you the self-tortured speculation bit where I delve into the possible origins of my persistent insecurity. All I want to say now is that, however strong or self-assured or even arrogant I may have appeared to you over the years, what I most wanted, always, was for you to understand me, to accept me, to tell me that the person that I am is alright by you.

Then one day you did. It was three years ago. On October 30, 2014, actually, the eve of what could have been the scariest Halloween of my life. This invigorating shot in the arm came just hours before Chris and I would sit down with a team of medical experts who claimed to have discovered a relatively successful protocol for dealing with the zombie apocalypse. Little did any of us know at the time that you, my friends, had slipped me a powerful antidote the day before, one whose real effects would manifest and multiply over the months and years to come.

On that Halloween eve, in my shock at having been abruptly relegated to the ranks of the undead, I turned to Facebook. As one does. And there you were, my imagined community, ready to inoculate me against the looming horror. A motley group of friends that reflected better than anything else the complex composition of my character—character and friends I would need now more than ever. Looking to you, I realized, was the best way of looking at me. The converse, I understood, was equally true.

Mirror, mirror, I began. A weird approach to fighting cancer, admittedly. An indication I’d spent too long in fairytale land as a kid. As wild-eyed Joyce Byers of Stranger Things has repeatedly insisted, “I know what this looks like!” By that, of course, she means BATSHIT CRAZY. Unless you happen to be the one who has found a way to talk with your missing son via Christmas lights. Or who feels you’ve discovered a “cure” for your disease in regularly confiding your deepest fears and greatest foibles in the world’s most public forum.

Self-reflection, I quickly discovered, can look an awful lot like an exercise in vanity, its mirror-image and near enemy.

Just as poison can serve as medicine.

Patriotism can resemble treason.

Standing up can involve taking a knee.

Abuse can masquerade as tough love.

And, if you should find yourself suddenly separated from everything you hold dear by the thin wall concealing an eerie dimension you never suspected could exist, then your frantic effort to break down that space-time barrier with an axe or whatever goddamn tool you happen to have on hand will likely appear to many concerned onlookers as the textbook sign of a nervous breakdown.

(Note my weapons of choice: a pen, a child’s fork, a pair of scissors, needle-nose pliers, lip gloss, and a few fake bullets.)

If any of my soul-searching exploits of the past three years ever struck you as exhibitionist—just the sort of self-absorbed, navel-gazing, attention-seeking, ego-driven kind of behavior that gives social media its bad name (well, that and the whole selling-out-to-the-Russians thing)—you are not alone. On many occasions, I myself came to question the methods I’d adopted and to ask what hidden motivations my sneaky subconscious might be cleverly concealing.

My closest friends and family shared these concerns, but whenever they voiced them I justified my Facebooking and blogging and memoir writing as so many means to achieving a noble and necessary end: healing.

Of course, even as I emphatically defended myself against charges of look-at-me narcissism, I was fully and uncomfortably aware of the fact that how we arrive at our destination is bound to change the very nature and outcome of the journey itself.

Social media can have a terrifically corrosive power. We know this. Evidence that these platforms can fracture and divide our community more than they unite us is everywhere apparent. Many social scientists have taken to the soapbox of late, screaming that our devices have made zombies of us all, preaching that the end of the world is nigh, and offering statistics to back their claims.

Showing up regularly in such a fraught virtual environment was a risky proposition, I knew, being all too aware of our susceptibility as humans to the lure of likes, the intoxicating effects of flattery, and the tendency to get greedy and hoard the sort of social capital such attention bestows. Hip to all this, I was a bit like Will Byers, understanding that, even if my initial intention was to use my insight to spy on the Shadow Monster in the hope of defeating it, I could easily end up a double agent in the employ of pure evil.

But whatever. It didn’t seem to matter how often I flipped the perspective switch during those internal debates about the advisability of “performative self-examination,” as I’d come to think of it. I always found myself coming back here, to this massive virtual theater, and awkwardly uttering “Ahem” to get your attention.

Driving my actions was something far more powerful than what the visible world was willing to reveal. Like Joyce, I felt what I felt. I knew what I knew. This was a salvage operation; at stake was not only the rebuilding of my body but the redemption of my soul. To hell with what it looked like. Just sell me the fucking Christmas lights, Donald. And yes, I mean on credit.

There’s something seriously wrong with me, I began by admitting to us all three years ago. And to the public confession that I was harboring a horrifying thing at my core, you responded with 162 likes, 146 comments, and 24 shares, which combined told me what I’d always secretly hoped to hear: that you liked me anyway, that some of you even loved me, and that you cared whether I lived or died.

It was a glorious and strange occasion, like attending my own funeral. Announcing my diagnosis helped us all dump our inhibitions in a screw it, let’s hug sort of way. Within the space of an instant I received this rare and beautiful gift: learning how you felt about me without having to die first.

Everyone should be so lucky. Seriously.

You and I wanted to have a moment, right then and there, while it was still possible. We felt compelled and instinctively driven to enact a basic human transaction at the brink, for our mutual benefit. What we had to figure out were the terms of our trade.

Conventional wisdom says cancer patients need casseroles. While my kids thank those of you who cooked to show you cared over the six-month period when I found even the taste of water overpowering and insufferable, what I most wanted for myself was something very different, and really hard to ask for: an audience.

Hard because, if asking for pretty much anything is awkward, it can be downright mortifying to walk up to the mic and announce, “May I have your attention, please? I have something very worthwhile and important to say.”

Especially for a 5’2” female who indulges in self-doubt the way that others devour a pint of ice cream (ok, I do that, too). Inviting you to read along as I muddled through some early responses to The Big Questions, I was always excruciatingly aware of the bigness of my ask. Time is precious, after all, and far greater voices than mine constantly compete for your attention. But there was so much I wanted to tell you. So much, in fact, that I was dying to tell you.

However lovely the intentions behind donated comfort food, forcing myself to enjoy it in the context of my cancer felt a lot like roasting marshmallows while my house was burning, to be perfectly honest. Every one of my instincts was fully engaged in the all-consuming survival effort, and there was a clear consensus among those deep and shrill interior voices that, if my existence was to mean anything at all to this world, I needed to express myself 1.) immediately and continuously, 2.) to the exclusion of many other worthy pursuits, 3.) within hearing range of an audience, 4.) without any hope of reward beyond simply being heard.

Here’s something you may have figured out about me by now: I am no good at playing the part of Helpless Cancer Victim. No more than I can pull off the role of Classroom Party Mom. “Don’t count on me for cupcakes,” I recently explained to my daughter’s first-grade teacher. “But hey, if you’re open to some curriculum enhancement, I’ll bake you up a big batch.”

Please understand: this is not me acting all smarty-pants, holier-than-thou, self-righteous, proud-to-a-fault, or ungrateful for your concrete aid when I was at my lowest. This is not me judging all of those compromised folks who legitimately need casseroles, or even those who are getting on just fine but would like to enjoy a steaming bowl of consolation without a side dish of complicated, thank you very much. Nor is this me looking down my nose at the phenomenal cupcake bakers of this world who brighten our kids’ days (I love you ladies for all you do—and yes, it’s almost exclusively ladies who do this very important work). It is simply a matter of me knowing me. Of me understanding that the best of what I have to offer is something far less comforting than casseroles or cupcakes, but just as important.

For the better part of my life, most folks haven’t known what to make of me. Like Carla Bruni, “je suis excessive” by nature. I was always too much for people. Too intense. Too far out there. Too eclectic. Too intimidating. Too earnest. Too touche-à-tout (all-over-the-place). Too outspoken. The proof? I just compared myself to Carla Bruni, France’s perfectly bilingual supermodel, actress, singer songwriter, and former First Lady. Who does that?

I’ll tell you who: the sort of person who has been looked at askance, questioned, criticized, and reined in all her life for expressing this brand of intolerable excess.

Someone should really take you down a peg or two, I’ve heard more than once.

You think you’re so great.

On whose authority do you make such claims?

Goody-goody!

Who do you think you are?

Can’t you just focus on one thing at a time?

Stop pointing your finger at me!

What makes you think you have something worthwhile to share?

How about you just shut up already and give someone else a chance to talk?

None of which felt good. If those voices had it right, I’d be forced to conclude there was something seriously wrong with me. The prospect of approaching life in a fundamentally different way would necessarily mean fighting the wild nature even my name told me I was meant to embody.

But still the voices persisted. Which is likely what led to my most valiant effort at shutting myself up: a 13-year relationship in which I was actively discouraged from expressing myself in almost every way imaginable.

Then the most amazing thing happened: I got cancer!

Again, an admittedly excessive thing to do. Not something I’d exactly gone and signed up for. But I’ll be damned if this illness wasn’t the perfect antidote to my lifelong alienation problem.

Suddenly, nobody begrudged me my excesses. No one wanted to be in my shoes. Nobody envied my lot in life. People pretty much stopped telling me to be more this and less that. My body was not a source of jealousy or desire. My manic antics didn’t grate on people’s nerves, or at least not the way they used to. That old, persistent claim that the deck had been stacked in my favor was abruptly dropped. And just like that, after a lifetime of curbing my natural élan so as not to make people uncomfortable, after decades carrying guilt over what I’d been given and wearing shame because my very being could often seem an unwelcome excess, I was finally free to just be me.

The jig was up. My cancer had outed me, revealed what I’d long been concealing. And the only way to spare folks discomfort was to hide the fact that I was sick… which of course could only make me sicker. Repressing, stifling, conforming to expectations—this cautious approach had clearly been unhealthy. Besides which, following all the rules had failed to keep me safe from mortal danger.

Call me crazy, what others saw as a tragedy I experienced as a liberation.

In the Upside-Down, I felt quite suddenly well-liked. Welcome. Just right. The sensation Alice must have felt when she finally stopped growing either too big or too small. Or the comfort Goldilocks found in tasting Baby Bear’s porridge, sitting in his chair, and sleeping in his bed.

The natural bravado and intensity I’d carried into many of my earlier endeavors and that had often struck observers as problematic were instantaneously recast in a heroic light. Whereas in the past I’d been accused of overreach and gaudy showmanship, now the very same gestures were perceived as acts of “incredible bravery” and “kick-ass determination.”

Thanks… I guess? I stammered, totally baffled, knowing that this “amazing courage” people spoke of was nothing more than me being me, only the context had shifted dramatically. The extreme nature of my circumstances finally seemed a good fit for my own radical character. My fearlessness finally had a proper outlet. This is going to sound weird, I know. Offensive, even. But I immediately knew that cancer was going to be easy compared to feeling unliked. That had been excruciating. This would be a walk in the park.

I’ve got this, I assured everyone.

But what I was really thinking was: Holy crap, I was made for this shit.

Ever hear the story about how Br’er Fox wanted to kill Br’er Rabbit in the worst possible way? “Hang me from the highest tree!” pleaded Br’er Rabbit. “Drown me in the deepest lake!” he implored. But please, PLEASE, p-l-e-a-s-e don’t throw me in that there briar patch!” Which is precisely what Br’er Fox proceeded to do, letting predatory spite blind him to the fact that his prey had royally played him.

Like the tricky rabbit, I was born and bred in this here briar patch, my friends. Born and bred.

(to be continued)

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

it’s back

Today, my friends, is World Cancer Day. How exactly does one celebrate such an occasion, you wonder? That’s actually what I’m writing to find out. For starters it seems like a fitting moment to break my nearly year-long silence and tell you It’s back.

Not the cancer—I’m still “free,” as far as anyone can tell. No, what’s back with a vengeance is the sensation of living with an ugly and insidious thing growing inside me. The Get-It-The-Fuck-Out-Of-Me urgency that two and a half years ago made me drop everything, fall into a blue vinyl chair, and start blogging straight through my chemo infusions.

I still can’t explain by what internal mechanism this revelation about my compromised physical state triggered a visceral awareness that I’d been living with a different sort of malignancy for decades—a tangled knot of repressed emotion growing more potent and far-reaching as I happily went about the manic business of being a working mom. Or how I understood that my ability to heal bodily was predicated on my willingness to undergo a mental purge. Or how I knew with absolute certainty what I needed to do, even in those foggy predawn moments before the diagnosis had fully resolved into a clear picture of what awaited me in the days and months ahead.

Whether it was some atavistic survival instinct that kicked in or what they (dismissively) chalk up to “women’s intuition,” whether it was divine inspiration or something closer to unhinged delusion, at the very moment I received The Bad News I found myself in A State of Grace, like in a primal garden scintillating with dew where knowledge hangs low on the branch, hungry for the right mouth.

Glutton that I am, I bit. And instantly I came to understand that my body was a book I’d been writing for years without ever stopping to read it. At the center of my story was this malignant enigma, a living organism pregnant with meaning whose tendrils reached greedily through the space-time of my inner landscape, looking to occupy all my vital sites.

Stopping its spread and reversing the cancer’s insidious creep was the obvious goal of our immediate coordinated response. But as my three doctors each took up their weapons—poison, blade, and fire—I lay low like a meadow-turned-battlefield, bracing myself for the onslaught and devising an alternate plan, knowing that the only way to truly best this beastly part of me that fed on darkness was to draw it out, into the light.

So I painted my face. Obviously. Spent a week wearing only dresses. Naturally. Loitered seductively at the mouth of what I guessed might be my deepest emotional cavern. Patiently. Until one day, in the small round mirror of my compact case, I glimpsed a dark shade emerging against a background of shadow. Taking a sultry step forward in my red two-inch heels, I watched discretely as it advanced with predatory appetite, hypnotized by the allure of an easy meal. And at the very moment it crouched to pounce, I turned to face my Beast-Me.

Go ahead, I told my cancerous self, feeling beautiful for once and more powerful than ever. Show me how ugly I am inside. You will not be the first.

My plan wasn’t particularly well-formed. I was totally winging it, to be honest. With hindsight though it’s possible to list the major steps of my cancer-fighting campaign as:

1. Perform strength to psych myself up for the encounter.

2. Position myself as bait.

3. Coax the unknown threat out of hiding.

4. Subject it to intense examination.

5. Force it to reveal its origins.

6. Love the thing to death.

All on my terms, in a place where I felt safe and strong and well supported.

In other words, I would write the cancer out of me.

Out, like, in the open. Words confided to a private journal were not going cut it. An invasive species so entrenched would have to be pulled up by the roots into the glaring light of day and subjected to full exposure. This pathogen and its attending pathos should be left to shrivel and wilt under public scrutiny, I understood, until having lost all potency conferred by me, their host, they would reveal their true, pathetic nature and leave me whole.

If you’re not an exhibitionist by nature, writing publicly about your intimate past and present is highly ill-advised. Maybe you’re someone who cares about what people think of you. Or maybe you have a family to protect, a job you’d like to keep, or competing interests and hobbies. In my case, all of these inhibiting factors were compounded by the muzzling effect of four hundred years of injustice perpetrated by the West, which we have systematically justified by painting the Other as radically different—a threat to be mastered, a contagion to be contained.

How could I possibly talk about my challenging 13-year relationship with my African ex-husband, who was also a Muslim, without perpetuating these longstanding stereotypes and adding fuel to the fire? How could I tell my story without doing more harm than good? Fully aware of the risk that my experience would be generalized and my words misinterpreted, I felt compelled to write all the same. Common sense and fear, I came to feel, were my greatest enemies. To build a bridge, you’ve got to reach dangerously across the gaping abyss.

All this to say that hitting “Post” was never a mindless gesture for me. It required a force of will that ran counter to reason, and caution, and instinct.

Announcing that I had cancer in a Facebook status update was admittedly a shameless bid for your attention, like dancing carelessly on a mountain ledge. But I wouldn’t have sought your attention if I didn’t think it was absolutely vital to my healing. You, dear friends, were the gentle sunlight that scorched my disease better than a daily dose of photon rays at +$3,000 a pop x 25 sizzling pops. It was because you agreed to bear witness to my self-designed form of treatment by reading me as I attempted to decipher the book of my body that I got better. You did that. Each one of you made a difference. And it didn’t cost us anything but time.

So now it’s back. That oh-shit-here-we-go-again feeling, like there’s some creature dragging its claws through my gut from the inside. Only this time I’m even more reluctant to write publicly. For one, I’ve been writing privately, trying to build a bigger bridge, in silence, and that jealous pursuit demands all the attention I can afford to give it.

But, UGH. The world changed two weeks ago just as it did two years back with the diagnosis, and ten years before that when my first marriage ended: abruptly, dramatically, alarmingly. A rug has just been pulled out from under our feet, and with my introvert laid out in utter shock, my extrovert showed up, a rival sibling looking to compete for the same scant resources of time and attention, demanding I Do Something Now.

Don’t! shouted my introvert, albeit weakly from the floor. Keep to yourself, it pleaded. Focus your angst inward. Don’t be so arrogant as to think you have something of value to say in the here and now. Lay low. Leave this one to the activists and experts.

Reasonable arguments, all. But here’s the thing: on the subject of hostile takeovers, I am something of an expert. I devoted my doctoral dissertation to groups who used writing as a means of liberating themselves from their longtime oppressors. I lived for six years in a country that had only achieved its independence a generation earlier. Even more instructive, I personally survived the experience of being colonized twice: first mentally, by my domineering ex, then physically, by the cancer, whose insidious advance reminded me so much of the guy’s subtle way of methodically getting me to give up my freedoms, one by one, until it seemed I had nothing left. Claiming that others would be better suited to speaking out against the authoritarian power grab by the big bully now occupying the White House, that someone else would do a better job describing the risks his tyrannical methods pose to our liberty and national character, it’s all just bullshit, a way of shirking my responsibility.

So it’s with a certain authority that I can assure you: the cancer plaguing us today may wear a name other than ER/PR HER2-Positive Invasive Ductile Carcinoma, but it is just as deadly. It’s not only an oppressive ex haunting my own little psyche, but our current President doing a serious number on our collective consciousness. This shit’s not just in me this time, but it’s in you, too. And it’s going to poison the world over if we don’t all stand up to stop it now.

One of my first thoughts on getting the diagnosis was, Did I bring this on myself? My ongoing attempt to answer that question without wallowing in self-loathing has brought me on the greatest journey of my life, towards healing. The same can be true for us as a country.

Yes, we brought this on ourselves. But we also have the means to fix it. We are all cause and cure both. Niit niit mooy garabam, the Wolof proverb goes. Other people are our own best medicine. We need to turn and face this ugliness together, give ourselves permission to speak out, and shout a resounding Fuck No as one. The disease may have found its way into US, but in no way is it a definitive reflection of who we are. Not if we refuse to play host to its toxic presence.

So how should we celebrate World Cancer Day? I’ve come up with a couple suggestions, based on personal experience:

1. Start by making yourself feel good and beautiful and strong.

2. Don’t be afraid to draw fire. Welcome discomfort. Actively displace yourself.

3. Coax this shared malignancy out into the open.

4. Take a good, hard look at it, understanding that it offers us the blessed gift of insight.

5. Figure out where it comes from, and how it managed to take root within us.

6. Spread beauty and love in abundance.

Writing was the tool that best fit my own hand, but everyone has a custom-made means of expression, an instrument perfectly suited to doing the patient work of parsing out what’s healthy in us from what is corrosive. My girls got a great kick out of the Turnip sign that recently sprang up just feet away from the spot on Main Street where an enormous Trump sign has for months been planted like a foreign flag, causing Brewster residents to wonder who we are as a community.

Me, I can’t wait to see what you all come up with.

#worldcancerday#trumpturnip#resist#blacklivesmatter#nowall#nobannowall#cancer#sanctuary#antigone#longwayhome

3 notes

·

View notes

Video

vimeo

Could we call this African dance? Guest curator Sumesh Sharma (India) organized a performance to mark the opening of his group show at the Musée de l'IFAN during the Dak'Art Biennale 2016 in which five artists engaged with one another under the theme "India's Quest for Power 1966-1982." If the utopic dreams of solidarity among non-aligned countries in the postcolonial era have largely proven bunk, Bollywood at least has made significant inroads across the continent and has been assimilated into the African collective consciousness...

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

racines

you’ll find more images here

sculpture et texte de Jems Koko Bi

Terre brulée, Têtes brulées.

Aucune vie apparente.

Origine et identité assombries.

Signe particulier: Noir.

Provenance noire,

existence noire,

histoire noire,

rêves noirs.

Noir ni d’ébène,

noir ni de fumée.

Noir tout court.

ils existent ainsi.

Désormais, aucune ligne fantastique

qui délimite, qui dénomme, qui divise.

Impossible de déteindre le noir pour l’identifier

impossible d’identifier le noir pour le déteindre

un arbre sur mille survivra, faute d’identité particulière.

Têtes brulées, Corps brulés,

les enfants, les mères, les pères errant les bras tendus, à la recherche des siens. Les cinq sens devenus noirs, impossible de les repartir par descendance.

Le paradis se découvre et se morfond.

l’enfer sort de l’imaginaire.

Relevé de ses cendres, il abrite la vie. On ne peut plus l’inventer.

on change de monde,

Noir et enfer deviennent homogènes.

Leur fusion dense se reflète dans un magnifique bleu sombre où le noir reste le seul nom à tous.

Cet enfer vital et unifié est indivisible car quiconque prétend obtenir deux particules différentes en divisant l’unité, se fourvoie.

On ne fuit pas cette planète Terre pour une autre.

On fuit, et par contrainte, par rejet des différences, en demeurant sur la Terre.

Nous sommes devenus nous-mêmes les racines de nos propres arbres.

Provenance noire, existence noire, histoire noire, rêves noirs.

Noir est notre lumière.

Racines noires.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Just don’t lean against the walls

I’m on a bus parked in front of the Musée Théodore Monod, Place Soweto, better known as the Muséé de l’Institut Français de l’Afrique Noire (IFAN). Thanks to a wireless connection I can blog from anywhere, which I would be doing more often if images didn’t take so long to load. I’m working on it. In the meantime, you’ll find my photos on my Facebook page.

The opening ceremony got under way a bit late this morning. Here, punctuality would be surprising. Disconcerting, even. Things move “sénégalaisement”—that is, at the pace of a long and thorough greeting. Buul yakamti. Ne te presse pas. No need to rush. The beauty of each event reveals itself in the interstice between here and there, between now and then, between mine and yours. I learned long ago that it’s only in suppressing my impulse to impose an order on my days here that I find myself in precisely the right place at the right time.

While loitering in the courtyard of the IFAN museum, for example, drinking in the green of the rare grass and the refined date trees in this quiet corner of the city, I had the chance to say hello to Joe Ouakam, the undisputed guru of Senegal’s art scene.

Joe, the founder of Agit-Art was born Issa Samb in December of 1945. It was the year that many tirailleurs sénégalais having fought to liberate France came home to the unbearable hypocrisy of a colonized Senegal, where asking for the recompense that had been promised them—a meager veterans’ pension—could get them massacred by their “mother” country. Earlier that same year, eleven months before Issa/Joe came into this world, my favorite filmmaker of all time, Djibril Diop Mambety, had arrived, and the two extraordinary friends would later work alongside other artists and writers to agitate the cultural scene as early as 1970 through provocative works and collective actions that radically broke with Léopold Sédar Senghor’s Negritude, the reigning cultural imperative of the time.

I think I’ve always been a bit in love with Joe, and have secretly always wanted to be loved back. Today when he put his arm around me to pose for a picture, I held him like a father and thanked him deeply in my heart for the warm embrace.

It was while the guest curators were introducing the concept behind each of their shows, addressing the spectators from the balcony of the annex gallery, that Joe arrived on the scene from behind the crowd and announced his presence with a loud call-and-response sort of greeting, signaling the true launch of the event with his authoritative disruption. I couldn’t hear a word of what the curators had been saying, but Joe’s words, carried by the strong Atlantic breeze, found their way straight to my gut. Voilà, I thought. Le grand est là. On entre du coup dans le vrai.

On the ground floor of the gallery, guest curator Sumesh Sharma (India) had asked his artists to tape and paste their works directly to the walls. No frames, no fuss. No little foamboard card indicating the artist’s name and the title of each piece, as we are accustomed to finding in any exhibition. As to who did what, your guess is pretty much as good as mine.

Follow this link to see the images.

The dividing walls that the carpenters had finished just hours before the official opening were painted in the sublime sky blue referenced in the Biennale’s theme: La Cité dans le jour bleu, a reference to Senghor’s 1940 poem “Au Guélowâr,” which he wrote while detained in a German prison camp during the war. Rounding a corner, I made the happy mistake of touching one of these walls and came away from the encounter with sticky blue fingertips.

C’est parfait, I thought. J’y ai laissé mes empreintes. I will have left a trace after all.

#dakart2016#senghor#djibril diop mambety#joeouakam#issasamb#ousmane sembene#simonnjami#sumeshsharma#tirailleurs#biennale

0 notes

Text

Opening Day at Dak’Art

Full disclosure: what I’m going to show you is my own personal take on the Biennale, an event that I’ve had the privilege to attend four times, in 1996, 1998, 2000, during my Dakar years, and again in 2002, after I’d already moved back to the States. While this festival is international in scope, my account will naturally have a Senegalese slant. This is, after all, my second home. And by some astounding alchemy of fate and goodwill, of hospitality and great fortune, these are also my people.

I have so much to say, three languages in which to say it (creating a messy but delicious soup u kanja in my head), and only enough time each day to see, absorb, and throw a few quick dispatches into cyberspace. Later there will be time to extract the essence from each encounter, to analyze the work in depth and understand the source of its particular hold on me. For now, my job is to move with the current, to let go and allow the city to guide me where it will. I discovered long ago that Dakar loves me best when I approach her in this way, with open arms, not submissive but humble. Show me, I tell her. And wow, does she ever.

I left you in suspense last night, wondering whether all of the pieces—sent from Nigeria, Sudan, Ghana, Algeria, Ethiopia… and of course from Europe, where so many of these “African” artists live and work—would be released from Customs in time to make it onto the walls, and whether the walls themselves would be there to greet them. You will have guessed it: Simon Njami and his team managed to pull it off in time, and in grand style.

Here’s a taste of what was on offer at the International Exhibition this morning, housed in one of Senegal’s most fascinating sites—a real lieu de mémoire which we can only hope will be preserved and asked to serve its country once again—Le Palais de Justice, or Supreme Court, located at the very tip of Dakar in an area known as Cap Manuel.

Ndoye Douts (Senegal)

Aimé Ntakiyica (Burundi), A Family Affair (2016)

Each jar is labeled with a name and represents a member of his family, dating back to the 18th century. The jars are filled with colored beads.

Detail of a work by Lavar Munroe (Bahamas).

0 notes

Text

Behind the Scenes at the Biennale Dak’Art 2016

Palais de Justice. Dakar, Senegal. Monday, May 2. 10:30 pm.

Tomorrow the Biennale of Contemporary African Art will get underway. It is in this majestic building, abandoned for the past 24 years, that the international exhibition featuring 66 artists of African origin will be held under the theme “Reenchantments.” How it will ever be ready in time is what everyone is wondering at the moment.

Work in progress, by François-Xavier Gbré (France/Côte d’Ivoire).

Carpenters working late into the night at the Musée Théodore Monod (IFAN).

1 note

·

View note

Text

How to Suppress Your Superpowers

Let It Go, Part II

For Olan, whose powers are far more potent than mine.

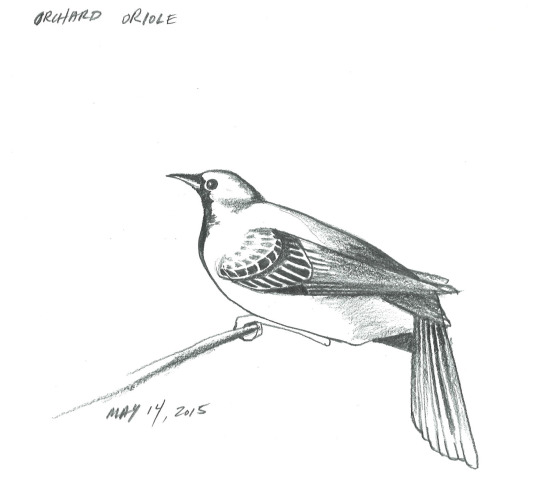

I’m sitting with Ava at the kitchen table, half of which is taken up by J. J. Audubon’s Birds of America. Today it opened onto a warbling vireo and I’ve accepted the challenge. As I shade the bird’s eye, leaving a spot blank to suggest the play of light on a shiny round surface, Ava gasps.

“How did you do that?” she asks, mystified, and I find myself in what Parenting Experts would call a teachable moment, presented with the opportunity to both quench my child’s thirst for knowledge and encourage further inquiry. Managing to suppress the self-critical impulse so common among women when offered a compliment, I briefly consider whether I should describe in detail each step involved in the process of rendering a three-dimensional object on a flat surface, or simply emphasize the importance of practice, patience, and persistence.

“Magic,” I state proudly, and immediately the Experts that occupy a small back lot in my conscience begin to protest, holding up signs that read “Parenting Fail!”

Ava’s not buying it either.

“Nuh uh,” retorts my natural-born skeptic.

“Yah huh,” I insist, thinking of the time I sketched the profiles of two eight-year-old boys as they played checkers along a crumbling cinderblock wall in a remote coffee-growing region of Sierra Leone, just months before civil war tore the country to shreds, then witnessed the pair’s utter amazement as they turned and saw for the very first time their likeness materialize before their eyes on my sketch pad.

I want my girls to believe in all kinds of magic. I hope they’ll expectantly await Santa’s visit for years to come, that they’ll continue to scout for fairies on the outer edges of our yard and, when swimming in the bay, will vie for a mermaid sighting well into young adulthood. These pretty possibilities enhance our experience, stretch the imagination, and reinforce the humbling notion that there’s always more at work in this world than what we mere mortals are allowed to see.

More importantly, though, I want Ava and Fiona to believe in their own power to radically transform reality at will. Among the critical life skills I hope they will develop is the ability to stare a stark situation in the face and still know that, when deployed at the proper moment, the right spell (which is really nothing more than a well-articulated goal stated out loud) can often instantaneously change seemingly intractable circumstances. Psychologists probably have a good term for this potential—something like manifesting, or self-actualization—but since even they can’t claim to fully explain the mechanisms at work in such cases, I’m sticking with “magic.” For starters, it’s really fun to say.

Around the house we talk casually about how Fiona’s awesome powers of cuteness could disarm a dragon, or how Ava’s clever charms could win her a battle of wits against a wizard, but the truth is, none of us yet knows the exact nature or full extent of these girls’ magic. My job as a parent, as I see it, is to cultivate in these wee people what Mambety called the “mad belief that anything is possible,” only tempering their confidence with enough realism to prevent them from actually stepping off a roof and attempting flight. Because, as we all know, anything really is possible.

If I should die before the girls are full grown, people will want to tell them who I was. If I’m lucky and have done a passable job at being human, a hundred hands will participate in sketching a composite portrait of me, shading it in stroke by stroke and giving dimension and a semblance of life to an otherwise flat image. Perhaps you, dear reader, will be one of them… and if so, please accept my thanks in advance. But for the love of all that is good, don’t read these poor girls my resume and leave them with the impression that I was a boring list of random and mostly esoteric accomplishments whose relevance is altogether questionable.

Tell them instead, in voice-over narration style if you want, or in grave tones with a British accent for effect, “Your mother was a very powerful sorceress…” Then explain that I was a good witch, sort of like Glinda, but whose fashion sense was definitely more in line with Maleficent’s. Tell them my magic was crazy strong and that, like Elsa, I spent many years suppressing it. But once I finally learned to control my powers and had the sense to know when to shelve them and when to use them, I was unstoppable. Tell them, if you would, the story I’m about to tell you.

When I came into this world one early morning in April of 1973, my first act was to piss off dozens of kids who’d saved up their hard-earned allowance money and biked to the Brewster General Store only to find a sign taped to the locked double doors announcing my birth. On that day, this 8lb 3oz baby girl was all that stood (or lay, I guess) between them and a bag full of Swedish fish and atomic fireballs. If some of them still hold it against me to this day, I don’t blame them.

My dad, who ran the Store, had been up most of the night helping my mother through a messy homebirth assisted by good old Dr. Whitelaw. At some point he had decided that placating my sister and brother with pancakes was a more pressing necessity than providing the town’s youth with its weekly share of sugar. But on the home front, too, I was already garnering resentment among my peers.

If you give your firstborn a common first name that begins with “J” and follow suit when your son is born a year later, naming the third child to come along in three years something outlandish that radically breaks the pattern is a sure way to create lasting sibling rivalries. Did my parents fail to realize that exceptions imply exclusion? In setting me up to feel special from birth, did they not know that I would carry guilt for all those who hadn’t benefited from such attentions, beginning with my own sister and brother? As the most obvious outward sign of a persistent and pervasive feeling that I was, if not destined to be different, at least desired to be so, the name that I unapologetically adore today left me feeling ambivalent through the better part of my childhood.

For as long as I can remember, whenever I’d get a bit cheeky or displease my mother in some awkward attempt at exercising my will, she’d first cycle through her repertoire of righteous maxims assimilated over two decades at Catholic school, then close with a clincher: When I First Looked Into Your Eyes.

“The moment I held you for the very first time,” she would begin, calling up for me the bloody bedroom scene pictured in those faded Polaroids, which always struck me as more horrifying than evocative, and less valuable as souvenirs than as proof to counter my siblings’ claim that I’d been adopted. “…Looking into the eyes of my newborn babe,” she’d continue melodramatically, “what I saw there was so powerful it frightened me. In that instant, I knew I was no match for you.”

In short, I scared the living shit out of my mother. As a baby.

When I First Looked Into Your Eyes was not meant to boost my confidence or imbue me with a sense of invincibility while growing up. The critique implicit in this story—my story, which was delivered more like a cautionary tale than a fairy tale—was never lost on me.

“You were born with the ability to get anything you wanted,” she’d say, like an indictment, invariably adding, “Within seconds you had your father wrapped around your little finger.” Which was how my sister explained the clear injustice in the fact that, at age ten and as the youngest child, I was the first to get skis for Christmas. If Dad didn’t have the money to buy three pairs at once, why hadn’t he started by equipping his eldest? She had a point, I conceded at the time, and agreed he should return them for a refund.

Repeatedly told I possessed powers that would wreak havoc if abused, I grew to distrust myself and often experienced guilt over things I hadn’t done but ostensibly could. With a name that never failed to get me noticed, I felt bad for attracting attention I’d never actually sought. And, though I was thrilled by every means of expression available to me, I eventually came to feel that I may have arrived on this earth with too many gifts, as if in statu nascendi I should have devised a way to share this bounty with other beings yet unborn.

“Why did you have to take art from me?” my brother asked me once from a payphone in Maryland, four years after he’d joined the Marines. It was our first heart-to-heart since our high school years had introduced a very long, awkward silence into the easy—if rough and tumble—relationship we’d had as kids. “You were good in school. You were good at sports. You were such a good girl, eager to please. All I had was art,” he confided. “Did you really have to get good at that too?”

The knowledge that I’d unwittingly committed such an egregious theft against my own brother broke my heart and might help to explain why, when my first husband drew a line in the Senegalese sand and insisted that art was his domain and writing mine, I agreed to limit myself to a single mode of expression. And perhaps it was the deep distrust, long cultivated by my mom, in my own ability to control these supposed superpowers that led me to marry a man who insisted he was immune to my charms.

“What do you love about him?” a former teacher of mine once asked, and was no doubt shocked when I responded, in all seriousness, “He keeps me in check.”

But would I, through my adolescence and well into young adulthood, have sought guidance from such gurus who claimed I needed domesticating or taken shelter from my own self within the strictures of religious and academic institutions if, along with my name, I had been given to understand that a meadow is, by definition, wild? That any grassy enclosure with a fence around it is not in fact a meadow, but rather a common field?

It took me decades to recognize meadows for what they are—self-regulating ecosystems that resist cultivation and manage quite naturally to curb their own excesses, thank you very much. They are the stuff of poems and pastoral scenes. They are where fairies gather under a full moon and where secret lovers meet at midnight.

Meadows, my friends, are magical. And I’m done trying to pretend otherwise.

0 notes

Text

Let It Go

Fiona wants to know if I like Frozen. She is sitting across from me at the kitchen table applying a small snowflake sticker to the side of her nose, because at four and a half piercing it is still out of the question. I sense an urgency to her question, like there’s a lot riding on my response.

This Thanksgiving will mark two years since Disney’s megablockbuster unleashed a frenzy that had even the shyest young girls from Alaska to Zimbabwe throwing their arms back in defiant abandon and belting out “Let It Go” as if they’d all been caged and muzzled since infancy.

In our household, though we did little to feed the Frozen flame, it was clear from the start that fighting it would be futile. All it took was one Christmas and a couple of birthdays to transform our girls into walking, talking advertisements for the franchise, thanks to well-meaning friends and family anxious to see their pretty little eyes sparkle with delight. At the height of Frozen Fever, Ava and Fiona would daily don their shimmering ice-blue dresses and take turns strumming their Frozen ukulele while sipping imaginary hot cocoa from plastic cups featuring their favorite characters. I kept a running daily tally of Olaf impersonations. “Watch out for my butt!” one would shout a propos of nothing, sending the other into a fresh round of giggles. When I wasn’t looking, they would surreptitiously paint their nails with sparkly blue polish and coat their lips with matching gloss from China, until I disappeared the stuff for fear of toxins.

Every chair in the house became a stage. Every picture my girls drew featured a princess with a long side braid standing near an ice palace. Every game of make believe ironically starred Fiona as Elsa—the older of the two sisters—simply because she’s blonde, with Ava dutifully assuming the role of the younger brunette, Anna. Over the course of two long, brutal winters, every comment Chris and I casually made about the impossible amount of snow we were forced to weather invariably caused one or the other or sometimes both of our daughters to assume a power pose, stare into the middle distance, and spontaneously break into song.

“The snow glows white on the mountain tonight…”

When my brain eventually seized as a result of “Let It Go” overload, I responded to the girls’ desperate pleas to play it again by stipulating a quid pro quo: I would continue to subject myself to the soundtrack full of catchy earworms on condition that it be the French version. And so La Reine des Neiges sang “Libérée, délivrée…” and I managed to endure it, imagining I’d scored a small but significant victoire.

In the thrall of Frozen Fever, it was hard to imagine that a day might come, as it did last Wednesday, when Fiona would nonchalantly offer her beloved Elsa doll to a friend as a parting gift at the end of a playdate. But a few months ago, to our great relief, her longstanding obsession with yellow duckies began to wrest her attention from the ice maiden’s iron grip, and today our refrigerator is once again covered with pictures of duckies driving ducky cars wearing ducky slippers and eating ducky candy. Which is why Fiona’s recent inquiry into my feelings for the movie threw me. I’d kind of figured we were over it.

“Yes,” I assured her. “I actually do like Frozen.”

Actually, because my daughters are well aware of my visceral aversion to Barbie, at the mere mention of whose name I routinely pretend to retch ever since their aunt sent them home from a visit brandishing a copy of the horrifying book “Barbie on Safari” as some kind of sick joke on their feminist mom with a Ph.D in Francophone African Studies.

Why does Barbie make Mommy want to throw up, you ask? Well, girls, since I generally make a great effort to avoid using certain words in your presence—hurtful words, such as “hate” and “stupid”—and since it’s not nice to call someone a “vapid bimbo,” let me put it this way: anyone silly enough to drive a hot pink jeep onto the African savanna and to express more interest in her wardrobe than in the wildlife around her deserves to be mauled by a pack of famished lions and torn limb from anorexic limb.

Does that answer your question?

Inserting the qualifier “actually” in my response to Fiona was also meant to foreground Frozen against the backdrop of our countless conversations about princesses, for whom my general indifference is similarly well documented. In principle, I have nothing against young ladies in frilly dresses. It’s just that I prefer my female heroines active, reserving my admiration for those who achieve their fame by accomplishing amazing feats, not by mere accident of birth or thanks to their ability to tolerate tight corsets and hoop skirts wrapped in countless yards of taffeta—not an easy task, no doubt, but one that smacks more of poor judgment than of talent.

Want to impress me, I ask my girls? Become an ultra-runner like Diane Van Deren, who routinely beats the pavement (or the desert sands, or the arctic tundra) for hundreds of miles without stopping to sleep, and this despite her debilitating epilepsy and the major brain surgery meant to cure it. Start a blog at age 11 advocating for equal access to education for girls in Pakistan, as Malala Yousafzai did, and after the repressive Taliban shoot you in the head, advocate even harder. Walk a 2 ½-inch-wide tightrope across Niagara Falls behind Maria Spelterini, then perform this death-defying act again days later with buckets on your feet and a paper bag over your head. Then do it shackled. Then while dancing.

Or try being born black like Bessie Coleman, the thirteenth child of sharecroppers in rural Texas at the turn of the 20th century, and against all odds proceed to become not only the first licensed African American airplane pilot, but the first American of any gender or race to hold an international pilot license. Trade in your petticoats for a practical pair of pants and become a pirate of the Caribbean like Anne Bonny and Mary Read, who successfully commanded a crew of drunken outlaw sailors. Earn a decent living from your writing as a woman in medieval France, following in the footsteps of Christine de Pizan, who miraculously managed to produce over forty well-read works when the man she was married off to at age 15 suddenly died, leaving her alone to support her ailing mother and children. Save hundreds of thousands of lives by inventing something like Kevlar, the superstrong material that protects our soldiers, as did chemist Stephanie Kwolek back in 1965. Or, if you want to see what it’s really like out on the African savanna, you could join South Africa’s mostly female Black Mamba Anti-Poaching Unit, made up of women willing to face ostracism from their communities to protect endangered black rhinoceroses and other wildlife from greedy bastards with automatic weapons. These ladies are smart enough to suit up in khakis and cammo, not hot pants and ball gowns, allowing them to effectively perform a difficult and dangerous job for which the world owes them a great debt of gratitude.

While the accomplishments of Frozen’s princesses fall somewhat short of those mentioned above, I can’t help but like these young ladies nonetheless. And it’s not because of any extraordinary quality or amazing feat that sets them apart. On the contrary, it’s because, for the first time in watching a Disney princess flic, I find myself relating in a deep and wrenching way to Anna and Elsa’s emotional highs and lows.

And here, at the risk of alienating you, dear reader, I must make a confession. Even after two years of overplay, every time I hear “Let It Go” I shamelessly sing along. And every time, without fail, I choke on some verse in the goddamn song and begin to cry. I’m willing to bet good money that I’m not the only one.

Secretly, and maybe only subconsciously for most, I think we ladies have all been dying to tear down the defensive walls we’ve been made to erect from the time we were small (“Don't let them in, don't let them see / Be the good girl you always have to be”), to cast off our inhibitions like a tight corset (“The wind is howling like this swirling storm inside / Couldn't keep it in, heaven knows I tried”), and for once find out what we’re capable of when we access our true powers and allow them to flow full force into the world (“It's time to see what I can do / To test the limits and break through / No right, no wrong, no rules for me… I'm free!”).

I did that once. And man, was I potent.

To be continued…

0 notes

Text

On Beauty and the Beastly

>> Part VIII,The Unwitting Operative of 2041 Mermoz <<

One of the disadvantages of making art from trash is that the result can end up looking pretty trashy. This fact only really registered as I watched Modou and François haul a life-sized sculpture of what looked like a mangled corpse encased in a makeshift casket into the courtyard of the U.S. Ambassador’s pristinely manicured residence. While they struggled awkwardly to prop it upright against the compound’s security wall on the far side of the swimming pool, I turned to Judy Smith, the ambassador’s wife, and smiled hard enough to tear her eyes away from the morbid piece. She had that same mildly horrified look on her face as when I’d handed her our group’s manifesto the week before, one that suggested I had repaid her generosity and trust with a bait-and-switch ruse.

“What a lovely home you have,” I said, stupidly, stepping into her line of sight when I saw Modou attempting to secure the corpse to a bougainvillea bush by winding a rope tightly around its neck. The compound, now littered with artwork waiting to be hung, was indeed lovely. With a rare tropical tranquility that only an armed Marine Corps guard could ensure in this needy and bustling city of two million, it was, however, no more a result of Mrs. Smith’s attentions than the White House could be considered a direct reflection on Hillary Clinton’s skills as a homemaker. Madame l’Ambassadrice might choose to replace the curtains and add a platter or two to the residency’s already large collection but, like the First Lady, she was decidedly not the type to indulge in many such exercises in futility. Higher ambitions motivated this five-foot-two powerhouse, who had no sooner arrived in country than she’d begun actively promoting efforts to increase girls’ attendance rates at schools across Senegal, among a handful of other pet projects. This excessive eagerness to make a difference is something she and I seemed to share, only the diplomat’s wife had far greater means at her disposal.

Maybe it was a kindred spirit she’d sensed in me when we were introduced, just a month or so earlier, at the office of an NGO run by a couple of former Peace Corps volunteers where I regularly traded translation work for the right to use their printer. Or maybe it was a pity case she’d seen when I, in my thrift store finery, had explained I was in Dakar working with a group of young artists practicing found-object art and striving to bring attention to the marginal and the outcast. Either way, when Mrs. Smith heard we were looking to display the products of our nine-day art workshop at various sites around town, she didn’t waste a moment in deciding we could use her help.

What Mrs. Smith had failed to consider when offering—entirely sight unseen—to host an exhibition and reception in our honor was that presenting these works at the U.S. residence amounted to conferring on them an official American stamp of approval. For all she knew, the reclaimed materials my friends incorporated into their artwork might be sheep’s blood, Soviet-era propaganda posters, and some of the Koran’s more bellicose verses. A bit of due diligence on her part would have been in order, frankly, given that legitimizing such provocative pieces would undoubtedly be a source of both diplomatic and marital strain. But Mrs. Smith’s Midwestern assumptions about the nature and purpose of art had apparently left her unprepared for the possibility that what we had to offer could be anything but harmless and aesthetically pleasing.

Fortunately for her, the young members of ART Horizon were just as intent on establishing themselves in the art world as they were on upsetting the status quo. While their particular form of provocation didn’t court the sort of controversy that Chris Ofili managed to attract by mounting his 1996 pornography-studded collage titled “The Holy Virgin Mary” on two piles of elephant dung, it aimed all the same to place the public face-to-face with the sometimes foul reality in which these artists operated, where the abundance of refuse in their urban environment could seem reflective of their status as global rejects.

Senegal, like most African countries, had long served as a dumping ground for what the West no longer wanted but couldn’t conscionably destroy outright: second-hand clothes, obsolete technologies, and vehicles unlikely to pass a rigorous inspection in their home country. It was a vast and ripe market for third-rate goods, for cheap knock-offs, for generic pills whose properties you just had to guess at. Because this society was neither structurally nor psychically equipped to handle the onslaught, the piles of waste in the streets of Dakar grew too tall to ignore, and while the same Westerners who were partly responsible for this mess chose to look away in distaste, there were my friends, Senegal’s newest crop of artists, picking through the trash and using it to fashion a meaningful response to the crisis of the everyday. The result wasn’t always pretty, as exemplified by the corpse sculpture, but did it have to be?

The obvious discomfort this morbid piece provoked in Mrs. Smith reminded me of a conversation I’d had with Bombay a couple years earlier. Setting out across the university campus on the first of three attempts at finding Dakar’s alleged art school back in 1996, he had asked if I believed beauty was universal. It wasn’t a pick-up line (he would deliver one of those a couple weeks later, when asking if I’d help him translate some important documents in the privacy of his mother’s bedroom while she, unfazed, sat just on the other side of the door chatting with a neighbor). We were new acquaintances still, talking as we walked alongside campus walls covered in political slogans with an easy familiarity that came of sharing a deep admiration for the same professor—Bachir, the director of my study abroad program and Bombay’s dissertation advisor, who had recruited him for this particular mission. At least ten years my senior but with only a couple inches on me, this slight doctoral student with a throaty Scooby-Doo laugh wore a variation on Bachir’s round-framed intellectual glasses and, like his mentor, struck me as genuinely kind and uncommonly willing to field my endless queries. I had wanted to know what exactly went on in a graduate-level philosophy seminar, and as he often did, Bombay responded with a question of his own.

Is beauty universal? The fact that an entire semester could be devoted to a single, seemingly simple question astounded me as much as my eventual discovery that Bombay was perfectly capable of translating those “important” documents himself. Until he put it to me, I realized I’d never really wondered whether the people and objects I considered beautiful had an intrinsic quality that others would equally recognize—regardless of their culture, race, class, gender, or age—or whether my personal take on these matters was actually a product of my place and time.

“So you guys sit around philosophizing about beauty and that sort of thing?” I asked, surprised when what struck me as a perfectly logical conclusion got him laughing.

“No, Meadow,” Bombay explained with patient amusement and a good dose of irony. “We don’t sit around talking about this sort of question. We sit around talking about how to talk about this sort of question.” I remember squinting in the bright sunlight, attempting to squeeze the essence of this distinction through the narrow channels of my brain. It felt a bit much, working at the same time to both take in the nature of philosophy and provide my new friend with a passable response to one of its age-old questions, but the challenge thrilled me. It was the same feeling I got with every eyeful of this place, which seemed like so many small pieces of an infinitely complex puzzle, and I sensed that putting it all together was quickly becoming an obsessive life project.

“What do you think?” Bombay asked, throwing me a line. “Would you and I, looking at the same three women, agree on which one is more beautiful?”

The Senegalese are a famously gorgeous people. Once you’ve lived in Dakar, you can stand on the streets of Harlem’s Little Senegal neighborhood and pick them out of a crowd of black faces with 95 percent accuracy. Typically tall with long, slender necks, the women have generous curves and the men are broad-shouldered and muscular. Their skin is a rich ebony and smooth, catching the sunlight at its best. Their eyes are almond-shaped and lined with dark lashes, as if with kohl. Years later, in grad school, I would come across an eighteenth-century travelogue by a French imperialist who, while he liberally applied the term “savages” to all Africans, couldn’t help but praise at great length the beauty of the those he encountered in present-day Senegal.

I scanned the faces of the female students gliding past us as we crossed the campus, so poised and proud. Each one struck me as more lovely than the last. If Bombay were to organize a lineup, randomly pulling aside three of these young women and asking them to stand next to me and two of my American housemates—whether African-American or white—I felt certain that the Senegalese girls would get all the votes from a diverse panel of judges.

But the answer wasn’t that simple. It didn’t explain, for example, why so many of our Senegalese counterparts used a toxic bleach cream to lighten their skin, or why they preferred to cover their own tight curls with wigs made of long, straight, synthetic hair. However prepared we Americans might be to concede no-contest in the face of both the sensual figures they’d been born with and the feminine graces they had perfected over years of practice, it seemed that Senegalese women (and presumably the men they were looking to please) had been conditioned to view certain white attributes as superior to their own.

Call it a disingenuous debate technique or the defense mechanism of someone who knows she’ll never be inducted into the Beautiful People’s Club, I answered Bombay’s question by slightly shifting the target.

“Why is beauty so important, anyway?” I asked. “Shouldn’t substance matter more than appearance?” Considering his question from a pragmatic standpoint felt more natural to me than bluffing my way through the rigorous contemplation of an abstract ideal. More than that, though, this response reflected my longstanding personal belief that content should be privileged over form, and explained why I’d always felt that the time I could have devoted to primping and preening was better spent doing something productive, like reading, or people watching, or even staring out the window.

“Yet here we are, searching for the art school,” Bombay retorted. “Isn’t this a quest for Beauty you’ve undertaken?”

I didn’t see it that way, actually. Art, in my view, didn’t have to be beautiful to properly perform its function in society. Beauty was more of a means to an end than an end in itself, I felt, and said as much to Bombay. The point of a powerful aesthetic experience was to move the viewer into a state of heightened emotional and ethical awareness, but there was more than one way to get a person there. By presenting an insoluble puzzle, for instance. Or by shocking the system. And to this end, ugly worked like a charm.

The monstrosity now prompting Mrs. Smith’s panic attack was not only supremely ugly, it was large and impossible to miss. As we stood there smiling politely, letting empty words fall out of our mouths into the void born of horror that had opened up between us, I sensed she was calculating how best to distract her guests’ attention away from the dreadful thing at the reception in our honor to be held the following day, or possibly worrying about what the USAID director’s annoyingly tasteful wife would think of her latest pet project, and maybe anticipating an unusually cool peck on the cheek from the ambassador at bedtime. I desperately wanted her to like me again.

“That sculpture was made by an artist named Cheikh Niass,” I offered out of the blue, pointing toward the mangled corpse and awkwardly interrupting Mrs. Smith’s description of the array of hors d’oeuvres her staff was busy prepping for the event. Then, like a brutal offering made to the god of good graces, I added, “He only has one arm.”

“My word!” Mrs. Smith exclaimed at this revelation, barely able to conceal her relief. Viewing the piece through the lens of the artist’s handicap seemed to fundamentally change her perspective on it. “However did he manage?”

It was Cheikh Niass’s right arm that was missing. I never found out how he lost it. None of my friends knew either, it turns out, since the capital Senegalese virtue of soutura, which we might call discretion or modesty, prevented them from asking. In a society that vilified left hands as dirty and base, having no recourse to the right must have at times weighed on Niass like insult added to injury. Here, the taboo on what the French call gauche and what the Italians call sinistre was so strong that people born lefty—Modou, for instance—quickly learned to suppress their natural tendency to favor that side of the body. Left hands, I had learned early on, were never to be used in any sort of transaction. Handing a person food or drink from the left was a sure way to disgust and alienate them. Similarly, money could only be offered from the right hand, otherwise an attempt to give alms would likely backfire and be perceived as an affront. If a person could potentially manage to get through a day in Dakar without entering into too many exchanges of this nature, in this community-oriented society there was no conceivable way to avoid the ubiquitous greeting, which invariably began with an “Assalaam alekoum” and a handshake. A poor or improper salutation followed by a request for directions would likely land you at the polar extreme of where you intended to go, I had been warned, just as one well-delivered could instantaneously endear even a toubab such as myself to a perfect stranger. I wondered if Niass always received the same treatment as a two-armed righty might after touching his only hand to his heart rather than respectfully extending it at this key moment of contact with the other.

According to the Senegalese art sphere’s internal calendar and sense of hierarchy, Niass didn’t belong to our “generation,” having graduated from the Beaux-Arts about five years before Modou’s cohort. A good number of his peers had agreed to show up for our closing ceremony at the art school, along with a half-dozen more established artists, but Niass and his buddy Jean-Marie Bruce were the only two who had accepted our invitation to participate in the workshop itself. Bruce, who lived in a house on the beach in the region known as La Petite Côte south of Dakar, occasionally wore the patchwork kaftan typical of the baayfalls, Senegal’s unique brand of Sufis who seek to achieve sublimation through humility and hard labor, though he struck me as more of a playboy than a mystic. Accompanying him at the workshop was a young white woman from Germany, also an artist, who wore a soccer jersey and who’d had her short hair braided into six or so childlike tufts around her head. Niass was more subdued in his style, but perhaps more heartfelt in his friendliness. Whereas Bruce had undoubtedly had more contact with toubabs—living on the coast where Europeans, in particular, seasonally flocked in search of sea, sex, and sun—Niass had the gentle eyes of someone who could see past my white skin with less effort than most.

What Mrs. Smith seemed to be asking was how, despite his handicap, the artist had managed to manipulate these materials into a life-sized sculpture. But having witnessed the entire process and gotten a sense of his personality, I was fairly sure it was precisely because of his handicap that Niass had gone for big and bold.

“He didn’t actually make the human figure himself,” I found myself explaining to Mrs. Smith, immediately recognizing my mistake as the diplomat’s newfound appreciation for the piece visibly dwindled. Now, in addition to ugly, the sculpture was unoriginal. Was I dead-set on disappointing her, or just genetically designed for self-sabotage?

“How unusual,” she replied flatly, and reached for the citronella candle on the patio table to center it ever so slightly. “Did he have some sort of helper then?”

“No, nothing like that,” I clarified. In the spirit of récuperation, Niass had agreed to work only with the discarded materials available either at the Beaux-Arts or in its immediate vicinity, using the limited supplies we’d purchased at the hardware store strictly as a means of fastening them together. The papier-mâché figure was something he had salvaged from a trash heap in the art school’s courtyard, probably a reject from someone’s class assignment. By incorporating the recycled artwork of a peer, Niass’s sculpture wasn’t exactly representative of the récuperation movement to which we were attempting to give form and voice, but rather like a metacommentary on our ideological mode of expression. Metarécup, I guess you could call it, though I don’t believe the artist would have put it in such pretentious terms. He had seen a body, complete with two arms and two legs, and he’d appropriated it, plain and simple. The frame he constructed around the figure could be interpreted as either a supportive structure or a set of constraints.

“He did all the heavy lifting and assemblage himself,” I stated somewhat lamely, sensing that my description of Niass’s method had left Mrs. Smith underwhelmed. She looked like she’d just been bit in the ass by a pet project gone rabid. Clearly, the ambassador’s wife had hoped to support something prettier, more authentic, less difficult to like. And to be fair, I could sympathize. If the corpse piece was at the extreme limit of what could reasonably be considered art, many of the paintings and sculptures produced during the workshop fell within a grey zone. Some were appealing, some compelling, some clever, but few of them were unequivocally pleasing to the eye, and not one would qualify as anything approaching a masterpiece. My own position as champion of and cheerleader for this movement would have been infinitely less uncomfortable at times had my artist friends been able to produce consistently stunning work. But this, I felt, was an unfair expectation to place on a group whose exposure to the sort of contemporary art they hoped to produce was limited, and whose access to the resources so vital in producing great art—namely time, materials, space, and freedom—was severely curbed.

You can adopt a cause, I wanted to tell Mrs. Smith, but you can’t domesticate it. Our job, I felt, if we were to be of any sort of use, was to hold space for these sometimes unsavory and awkward expressions, and to interrogate the discomfort they provoked in our comfortable first-world consciences.

1 note

·

View note

Text

my run

Yesterday, for the second time in two years, I ran down the middle of my hometown’s streets like I was living out some childhood fantasy of absolute freedom. Going into this year’s Brew Run, I had a few advantages over the person I was in August 2014, notably: shorter hair, a longer playlist, and a new set of really compelling reasons to run for my life.

I beat last year’s time of 44:28 by 18 seconds, but it wasn’t about breaking personal records or getting it over with fast. If these past months have taught me anything, it’s that the goal is not to stop but to keep going strong, for as long as I can. Pace it, I told myself. Push past what you think is possible, but don’t kill yourself trying to get healthy. Next week there’s Falmouth, I reasoned. In September you’ll climb Mount Washington.

I high-fived my aunties, Josie and Jeannie, as I passed Brewster Park, gave Andrew and Charlie Tobin a shout-out at the corner of Paine’s Creek and Stony Brook, signed a big thumbs-up to the Ring kids at Tubman’s first gooseneck then promptly scared the crap out of them as I screamed to get the attention of their neighbor—my big sis. The hill wasn’t as hard knowing that Ivy Tubman would be waiting just past the crest with a smile and some cool water, and when I made my shot, sinking the cup in the can from five feet away, the imaginary crowd went wild.

The real crowd was cheering—for brothers and mothers and daughters and cousins and grampas, of course, but for all of us, too—and I took the encouragement personally, passing it on mentally to Kristen Hilley, Forest Malatesta, Brendon Parker, Brendan O’Brien, Colleen Wherity Kelley, Brian White, Nena Manach Tobin, Sarah Macaulay Nitzch, Don Macaulay, Emily Ford Gallagher, Kristen and Kim Meagher... In these moments, surrounded by so many friends, I was able to take the full measure my community, which has grown even bigger and stronger over this past year, as my roots have grown deeper.

I kept the devil at my heels the entire way, thanks to The Devil Makes Three, and ran like hell for those who can’t, for those who left us too soon, for Mr. Stewart, and Mrs. Stewart, and Mrs. Talbot.

At mile four, I picked up the pace and must have passed about twenty runners before that old image came to mind, the haunting one of the sled dog named Searchlight who had so much heart she ran until it burst just ten feet from the finish line. When Mrs. Galligan read our sixth-grade class this tragic end to a sad story—describing how the death of his sweet Samoyed shattered Little Willy’s own heart, along with his dream of saving his grandfather’s farm—our teacher began sobbing uncontrollably, giving us our first insight into adult vulnerability. We giggled at the time, but we never forgot, did we? “Live with heart but keep it beating” has more or less, since that day, been my guiding principle.

Ah screw it, I thought, as I passed the five-mile marker and spotted Ava and Fiona, knee-high to their dad, waving and smiling wide. I’m gonna show my girls how their mamma can RUN.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Dana-Farber Day Camp (part II)

“It smells good in here,” Fiona says emphatically as we walk past Nuclear Medicine and enter the Radiation Oncology unit on Family Day at Dana-Farber Day Camp. I don’t want to tell her that the aroma she has mistaken for brownies baking in an imaginary oven behind the reception desk is actually flesh burning under the photon beam of a linear accelerator. It just doesn’t seem like the sort of thing a four-year-old needs to know.

“Want a snack?” I deflect, thinking of the basket filled with individually packaged Oreos, Fig Newtons, Goldfish, granola bars, and pretzels that sits tantalizingly beside the coffee machine in the break room. It is only 7 a.m. but, even at the expense of a nutritious breakfast, I am intent on proving to my girls that Mommy’s Hospital is not such a bad place.

“They’re free,” I add, realizing as I do that this perk is unlikely to impress my middle class children whose basic needs have always been met as if by magic. Weirdly, it’s grown-ups who get most excited about free snacks, accustomed as we are to being taxed at every turn. They are particularly appealing, I have found, when offered up to offset some unpleasant obligation, such as work. Mark Zuckerberg figured this out years ago, and the leadership at Dana-Farber has apparently concluded that, as with Facebook employees, so too for cancer patients: a spoonful of sugar helps the medicine go down.

I lower the basket of freebies to allow Ava and Fiona to choose. Naturally, they both go for the Oreos.

Neil is wearing a bow tie today, and it suits him, like he was born to man a booth at a county fair. During Orientation, my appointed guide delivered most of his spiel from memory, talking me like an auctioneer through each step of my new daily radiation routine and pausing to eye me meaningfully after each explanation. Did I have any questions? I didn’t, and he liked that. Having repeated these same words thousands of times, Neil is probably surprised that the sounds his mouth forms so mechanically still seem to make sense to other humans.

“You’re doing great,” he assured me.

“You too, man,” I thought.

I swipe my purple card under the grocery checkout scanner, informing the computer that I’m here, as usual, three minutes ahead of schedule. The computer, in turn, gives me a status update on each of the machines. Purple Machine is “On Time,” as is Green Machine. But Pink is “Down.” Neil had warned me this could happen. Zapping folks from 7 a.m. to 6 p.m. every weekday can put some wear and tear on an apparatus.

I imagine thirty or so Pink patients, rudely jolted from their daily routine, and predict that few of them, if any, will learn the news from the handy iPhone app that Dana-Farber’s tech team has created for this purpose, given that most of those whose paths I’ve crossed down here are over 65 and don’t strike me as particularly tech-savvy. Some will accept the reprieve with relief, no doubt, but others will likely be pained to see their completion date pushed back a day, as the technicians set about repairing the ray gun that has nothing pink about it and a make-up treatment gets tacked onto the end of their five- or six-week session.

A dedicated armoire at the end of the hall contains six shelves of johnnies stacked twelve to a pile, two piles to a shelf. In an adjoining dressing room, I remove everything from neck to waist and slip on the sky blue robe with 3D triangles, opening to the back. Over this, opening to the front, goes the cornflower blue robe with navy and red diamonds. The closest thing to this getup I’ve ever worn outside a hospital was a flowing brocade boubou, which looked stunning on my Senegalese sister-in-law but positively ridiculous on me.