Text

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

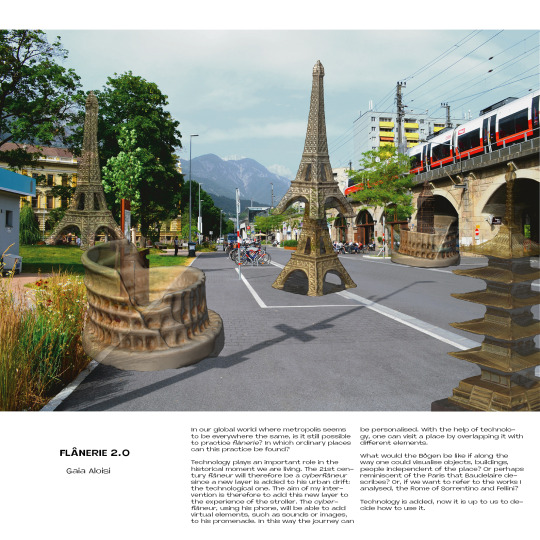

Technology plays an important role in the historical moment we are living. The 21st century flâneur will be a cyberflâneur, since a new layer is added to his urban drift: the technological one. The aim of

my intervention is therefore to add this new layer to the experience of the stroller. The cyberflâneur, using his phone, will be able to add virtual elements, such as sounds or images, to his promenade.

In this way the journey can be personalised. With the help of technology, one can visit a place by overlapping it with different elements.

What would the Bögen be like if along the way one could visualise objects, buildings, people independent of the place? Or perhaps reminiscent of the Paris that Baudelaire describes? Or, if we want to refer to the works I analysed, the Rome of Sorrentino and Fellini?

Technology is added, now it is up to us to decide how to use it.

1 note

·

View note

Text

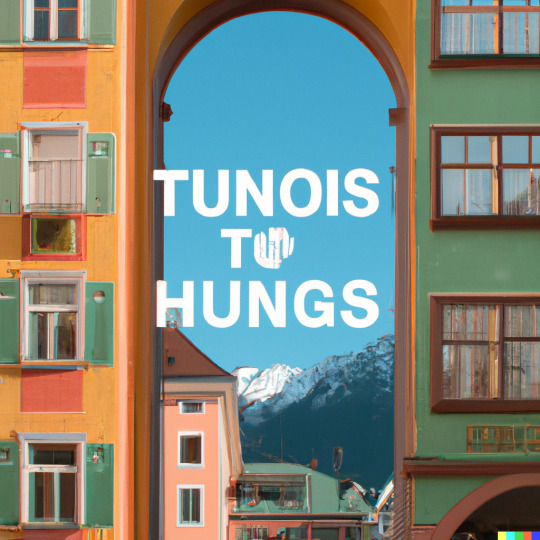

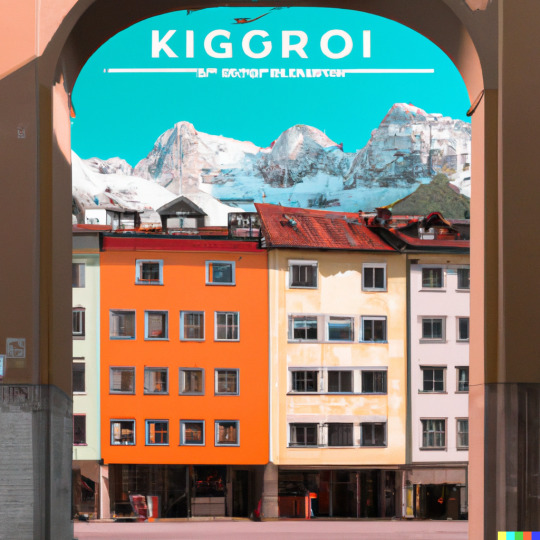

"the Bögen of Innsbruck as they were the location of a Wes Anderson movie"

images generated with DALL·E

0 notes

Text

In the Messager de l'Assemblée in 1851, Charles Baudelaire wrote On Wine and Hashish, illustrating the two themes in an extremely limpid manner. Modern, confidential reflections are dedicated to his readers, who lend their eyes, ears and palate to the author's provocative yet honest exposition of the grandiose aesthetic

experience that comes from taking alcohol and drugs and that leads, as in a fast track of life, to direct access for creativity. Baudelaire was an aesthete, a distracted stroller (flâneur), a revolutionary and a rebel. Lover of nightlife and its associated excesses.

Our urban intervention wants Innsbruck as a setting, so what would be the ideal habitat of the flâneur exploring that city? Which part of innsbruck could approach this lifestyle?

Bogenfest 2022

#architecture#city#memory#identity#everyday life#flaneur#strolling#urban intervention#innsbruck#bogen

0 notes

Text

Bogenfest 2023

0 notes

Text

a day in Florence

0 notes

Text

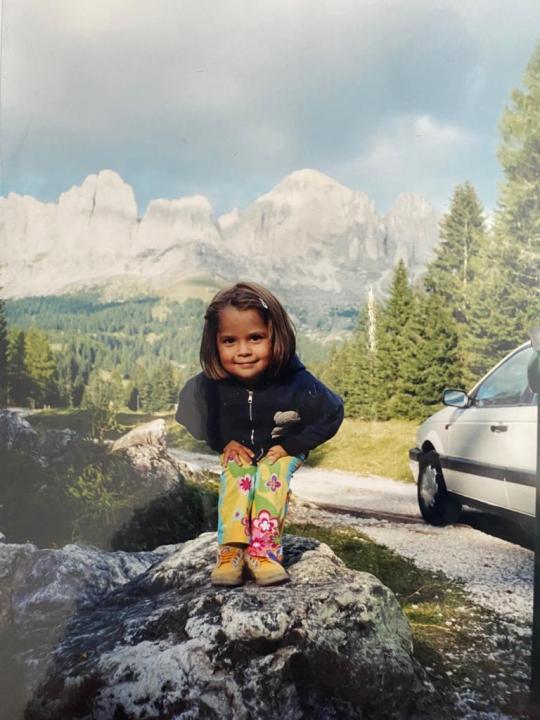

a day in the Dolomites

#architecture#city#identity#memory#everyday life#strolling#cinema#nature#landscape#dolomites#dolomiti

1 note

·

View note

Text

strolling through

Lago di Garda: Sirmione, Salò, Garda, Gardone

1 note

·

View note

Text

strolling through

Napoli and Costiera Amalfitana

0 notes

Text

strolling through

Roma

0 notes

Text

strolling through

Bolzano

0 notes

Text

strolling through

Innsbruck

1 note

·

View note

Text

Peter Greenaway

The Stairs

As cinema approached its one hundredth year, filmmaker Peter Greenaway (British, b. 1942) embarked on perhaps his most ambitious project to date: The Stairs. This massive installation project would take place in ten cities around the world over the course of a decade, with each installment focusing on one of ten themes related to the language of cinema (location, audience, projection, and so on). At the same time, each exhibition would be an attempt to push the medium’s language forward, displacing film from the darkened theater to the space of everyday life.

In 1994, Geneva, Switzerland, was the first city to host The Stairs. Greenaway and his team placed the custom-built white, wooden staircases at various locations around the city, from highly populated tourist sites to quiet residential streets. Though they varied in shape and size, the staircases were united by a common attribute: a circular “peephole” at the top, which offered a view that the artist conceived as a live, ongoing “movie” of the landscape. According to Greenaway, the staircases were “special viewing-platforms, modest positions of privilege from which to view the sites at all times of the day and night.” While the Geneva installation was followed in 1995 by one in Munich, Germany, the remaining eight were never realized.

Peter Greenaway—The Stairs: Geneva, the Location | George Eastman Museum

0 notes

Text

Travelling and standing still in themselves are concepts that clash with each other, almost a paradox, but somehow perhaps it is still possible. Photographs have an incredible power, for example those hanging beside the bed or those in the living room imprinted in beautiful photo albums that we rarely take a good look at; but sometimes you just have to look at them carefully and you are back on the road in no time at all.

That is why I think it is important to print and keep those pictures, not just the 'aesthetically pleasing' ones, but the ones that mean something to us, the ones that make us travel in our heads.

0 notes

Text

Elegantly attired, his gray hair swept back and curling at his neck, a handkerchief fountaining out of his jacket pocket, Jep is the very picture of the flâneur, the 19th-century urban stroller and spectator immortalized by Charles Baudelaire and in whom, Walter Benjamin wrote, “the joy of watching is triumphant.” What the flâneur watches is modern life, and other people.

Benjamin wondered why the flâneur, born in Paris, did not spring from the glorious archaeological sprawl that is Rome. “But perhaps in Rome even dreaming is forced to move along streets that are too well-paved.” He suggested that for a flâneur, Rome’s “great reminiscences, the historical frissons” are so much junk better left to the tourists. The tourist, that familiar figure of contempt, plays a crucial role in “The Great Beauty,” which opens with a prologue set in the Janiculum, a hill west of the Tiber. There, scattered amid busts of heroes of the Risorgimento, the 19th-century movement for Italian unification, a smattering of Italians mill about while a group of Japanese tourists take in the sights — a view, a city, a people, a history — that, Mr. Sorrentino suggests, the natives no longer necessarily see.

‘The Great Beauty,’ Starring Toni Servillo - The New York Times (nytimes.com)

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Great Beauty - La Grande Bellezza

Paolo Sorrentino

2013

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sorrentino’s film is suffused with nostalgia for origins: the Saint tells Jep that she eats only roots because ‘roots are important’; Dadina teaches Jep that real friendship means occasionally helping the other feel like a child again; Romano ultimately leaves Rome to return to his hometown, but not before writing a play that seeks to redeem nostalgia as the only thing left to those who have lost faith in the future; Jep’s ultimate redemption becomes possible only through a return to the home-bound memory of his first love.

This nostalgia for origins sits uncomfortably with Sorrentino’s repeated references, in various interviews, to the figure of the flâneur. He wanted, he says, to propose a re-valuation of the semantic potential of the usually maligned figure of the tourist, attributing to it some of the subversive potential formerly associated with the flâneur. But while the figure of the tourist is central to the film’s opening sequence, setting up the rest of the film as a reflection on the different gazes directed at the Eternal City – the flâneur’s versus the tourist’s – and while Jep, himself disillusioned with Rome, declares that ‘The best people in Rome are the tourists’, in various interviews Sorrentino seems to make no meaningful distinction between the flâneur and the tourist. When asked why he chose to make a film about Rome, he replies that as someone originally from the provinces, he ‘still look[s] at it with the eyes of a lover, a tourist…a Neapolitan in Rome’.

Narrating the ‘Eternal City’ in ‘La Dolce Vita’ (1960) and ‘La Grande Bellezza’ (2013) - NECSUS (necsus-ejms.org)

#la grande bellezza#the great beauty#sorrentino#roots#memory#nostalgia#flaneur#tourist#rome#city#architecture

0 notes