Text

Harvesting Wild Yeast

Generally it’s nice to brew with predictable ingredients in controlled conditions. You purchase your ingredients, follow your process, pitch your yeast, and leave your beer in a temperature stable environment. After some time the yeast consumes all the sugars and leaves behind its own flavor characters and some alcohol.

I decided that I’d carry out a little experiment to mix the process up a little. I wanted to catch some wild yeast. Yeast grows on a number of plants and also drifts through the air. In the old days people fermented things without even knowing what was causing it. Later brewer’s yeast was isolated and then carefully selected and bred to the different strains we use today. There is however no reason we cannot make use of wild yeast in our beers and see what we end up with at the end. Wild yeast tends to have a particular character and doesn’t ferment as clean as some commercial yeasts. Some beers rely on this unique character to create their particular flavor profile. In this post I describe a yeast capture I did recently. I will not describe isolating the yeast as this does require more specialized equipment, but what we’ll end up with will allow us to brew beer.

Equipment needed

You won’t need much to capture some yeast. There are two ways you can capture yeast: from the air, or from some fruit, flowers, or other piece of plant. I will cover the first one here, but generally it’ll be the same process for the latter.

So before we get started here’s what you’ll need:

One or two small jars with lids

Some muslin cloth

Dry malt extract

Small amount of hops (optional)

Rubber bands

A larger jar with an airlock in the lid

Process

First off we’re going to need to get our small jars clean and sanitized. For this I boiled them in some water for about 15 minutes with their lids and the muslin cloth.

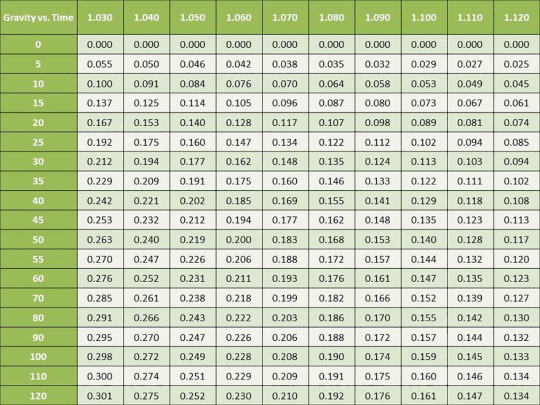

At the same time I prepared some wort with the DME aiming for a gravity of around 1.030. I used enough water to fill the two jars which was around 250ml, requiring about 20g of DME.

In this case I decided to add a small amount of hops (10 IBUs) which for this batch size is around 0.75g of 8%AA hop pellets. The hops add a little bittering and also help prevent the growth of some unwanted bacteria. I figured there would be no harm in adding that much, and if it prevents bacteria growing, all the better.

Once the jars were boiled I took them out (carefully) and left them to dry. Once dry I added some of the wort to each jar, placed the muslin on top and secured it with a rubber band and placed the lids back on until they completely cooled.

I decided to carry out my capture overnight in the winter, so I wasn’t too worried about the jars being a little warm, they cooled down pretty quick outside. I took the jars into my garden and placed them in two different places and removed the lids.

In the morning I replaced the lids and brought them inside. I poured both jars into a larger jar fitted with an airlock and left it at room temperature.

Now it’s a matter of waiting to see if you caught something and if it’s any good. It’s highly advisable to leave the jar for at least two weeks. The reason for this is that bacteria growth will start shortly after inoculation and peak soon after. Then yeast will start to grow and displace the nasties. After a few days you should start seeing the tell tale signs of fermentation in your jar. Bubbles, some foam, but don’t expect anything like high krausen.

Once it’s fermented out (2-3) weeks it will be safe to taste. DO NOT test or taste it before this time however. The presence of mold doesn’t mean your wild yeast starter is ruined, it’s just a common part of the process. If you have a pH meter handy, you can check the pH and see if it’s dropped significantly. That would also indicate the yeast has been working as the lactic acid concentration will increase after around weeks 4-5.

When testing, use smell first. If it smells OK you should use a sanitized pipette to pull a sample from below the surface and give it a taste. If it tastes good then you’ve got yourself your own awesome pet yeast. Otherwise bin it and try again.

Alternative method

As mentioned earlier it is possible to harvest yeast from flowers, fruit, and other pieces of plants. For this follow the above process but instead of leaving the jars outside simply place some fruit, leaves, bark, or whatever takes your fancy, into the wort. After a few days you should see some fermentation signs and a sediment will start to settle. No need to crush the fruit for this. If you notice the fruit going off remove it with a sterilized implement. Ideally leave the fruit 2-4 days and remove. Then leave the wort for a further 30 days.

I’ve not tried this method yet, but it is a similar method to capture yeast as above. You will find that different fruit, vegetables, and such will offer you different yeast types, so it’s a little more controlled than capturing yeast from the air.

Results!

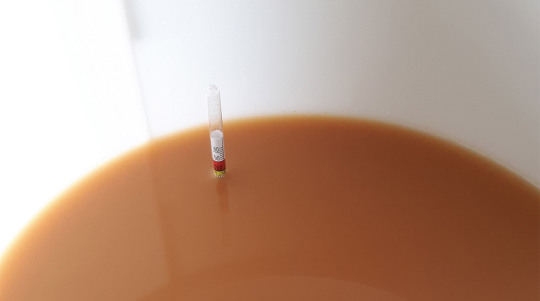

You should end up with a layer of yeast at the bottom of your jar that won’t look too dissimilar to what you’d see at the bottom of a starter. Here’s what mine looked like after 3 weeks, with a good yeasty layer at the bottom of the jar.

It had a very distinct flavor. A little sour and a bit earthy, but not bad, and I didn’t suffer any ill effects from sampling it. Unfortunately I ended up ditching this batch because I left it too long to brew with. But I plan on doing another capture now when spring arrives and more plants are in bloom.

Cultivating and isolating

If you are happy with the taste of your small beer then you can proceed to propagate the yeast. You can do this with step up starters, increasing the volume of the wort by a factor of 10 each time. So start with a 200ml starter with a gravity of 1.030-1.040 and leave that to grow ideally on a stir plate. Then pitch that into a 1.5l starter wort of the same gravity. At this stage you should have enough cells for a brew with an OG < 1.060.

Unfortunately this involves some guess work as unless you have the required tools to count how many cells your capture has, we’re just estimating the cell count. But hey, it’s free yeast, so just try again.

You can isolate the yeast cells in your capture, but that is outside of the scope of the article. For this process you will require a few more items like petri dishes, wire loops, alcohol burners, agar etc. There are a few resources online about wrangling yeast like this though if you wish to take this route.

Summary

Using wild yeast can lead to some interesting and very different flavors in your beers. If you end up capturing a good strain, you can always keep a small starter batch in the fridge and propagate from this for brews in the future. The strain will evolve over time, as it adapts to your brewing conditions and intermingles with other strains in the air, but that goes for pretty much all yeast strains.

So go hunting and have fun. Hope you catch something great.

by Sven Steinbauer

I live in the English countryside with my wife, two kids, and dachshund, having moved here from Germany many years ago. I work as a software engineer and enjoy figuring out how things work and learning how to do new things. I savor learning about and exploring the processes, different techniques, and ingredients that go into creating beer. With so many variables, adjustments, and ingredients, there’s a virtually endless combination of things to try out and learn about, plus you get to drink beer at the end of it. Although I enjoy a large variety of different beer styles, I still favor German beers most of the time.

Harvesting Wild Yeast was originally published on HomeBrewTalk.com

1 note

·

View note

Text

How to Brew beer in an hour (or less)

Let’s face it, most of us have jobs and other obligations that can sometimes make it hard to find the time to brew. So, brewing usually happens on the weekends. But what happens when life gets in the way, weekends fill up, but you still want to brew beer?

Here’s a method to simplify the brewing process to allow the homebrewer to brew a batch of beer in one hour.

This method was inspired by brewing Kombucha, which is a fermented tea. Props also need to go James Spencer of Basic Brewing Radio, who helped popularize the idea of the 15-minute boil.

In order to successfully brew a batch of beer in one hour, a few traditional homebrewing “rules” have to be broken. It should go without saying that the process uses extract with steeped grains. Secondly, the process uses 2-gallon batches – this lessens the time it takes to heat and cool the liquid. Third, it uses a 15-minute boil, and with such a short boil, you have to throw out the rules on hop additions. Once you accept these departures from traditional brewing techniques, you’ll find that it’s incredibly easy to brew beer in an hour.

Here’s the Cliff Notes version: Add specialty grains to one gallon of water and heat to 170 F. Remove grains and bring to a boil. Add DME and bring to a boil. Set timer for 15 minutes and add Bittering hops. Add Flavor hops at 5 minutes and Aroma hops at flameout. Add another gallon of refrigerated water and cool in an ice bath. Pitch yeast, ferment and bottle.

The One-Hour Brew Day Process

Start by heating one gallon of water and adding any specialty grains. When the water reaches 170 degrees F. remove the grain bag and bring to a boil add the DME and your first hop addition. The total boil time is 15 minutes, which is long enough to sterilize the wort. Add the next hops at 5 minutes and the last at Flameout.

The next step requires a bit of preparation. Grab a gallon of water from the store and place it in the fridge the night before you brew.

To cool your wort, make an ice bath and add the refrigerated water to the hot Wort and place the kettle into the ice bath. Every few minutes, give the Wort a swirl with a sanitized spoon. With this approach, you should be able to get the temperature to pitching temp very quickly.

Once at pitching temp, the process is the same as any other batch.

When you formulate a recipe using this method, you’ll need to experiment with the amount of hops. Hop isomerization, which is what provides the bitterness in beer, occurs when the hops are boiled. Alpha acids are isomerized (one molecule is transformed into another molecule that has exactly the same atoms, but the atoms are rearranged, according to Wikipedia) to form iso-alpha acids, which produce the bitterness. Since a 15-minute boil is shorter than a 60-minute boil, the result is less isomerization of alpha acids and therefore less bitterness. With a 15-minute boil, it’s common practice to double the Bittering hops, which will result in bitterness close to the 60-minute boil. If you’re adapting a 5-gallon recipe, keep the Bittering hops at the same amount, but reduce the flavor and aroma hops.

Aroma and Flavoring hops added after the 15-minute mark are close enough to the standard hop schedule to provide similar aroma and bitterness as in a 60-minute boil. If you have a complicated Hop Schedule, you can divide the time by 4, so a normal 15-minute addition becomes a 4-minute addition.

Here are two recipes using this method, a saison and a cream ale.

Saison

Grain Bill:

4 oz Crystal 40

2 lbs Light Dried Malt Extract

.5 lb Brown Sugar

Hop Schedule:

1 oz US Goldings @ 15 minutes

.5 oz US Goldings @ 5 minutes

.5 oz US Goldings @ Flame Out

Yeast:

WLP566 – Saison II 0r

Danstar Belle Saison

The Process:

Heat 1 gallon of water and add the Crystal 40 in a grain bag. Remove the grain bag when the temperature reaches 170° F. When the water starts to boil, add the brown sugar and Dried Malt Extract and 1 oz. US Goldings Hops. Boil for 15 minutes. 10 minutes into the boil, add .5 oz US Goldings Hops. When 15 minutes is up, add another .5 oz US Goldings Hops and remove from heat.

Move the stock pot to a sink or other container filled with ice and water and then add one gallon of cold water. When the temperature falls below 80° F, transfer the Wort to the fermenter and add the yeast.

When you think it’s done fermenting, take a gravity reading, then wait a day and take another reading. If the reading is the same, it’s time to bottle. If the reading changed, wait till the reading stays the same, then bottle.

Cream Ale

Despite its name, Cream Ale, doesn’t have any dairy products in it. The style originated in mid-1800s America as a response to the light German lagers. Traditionally corn has been added to the mash to help lighten the beer. In this case, we’re using corn sugar for that purpose. Cream Ale isn’t hoppy, or malty, but it is perfect for hot summer days.

Grain Bill:

2 lbs Light Dried Malt Extract

5 ounces Corn Sugar

1 teaspoon Irish Moss

Hop Schedule:

1 oz Cascade @ 15 minutes

Yeast:

Safale US 05

The Process:

Heat 1 gallon of water to boiling. When the water starts to boil, add the Irish Moss, Dried Malt Extract, Corn Sugar and 1 oz. Cascade Hops. Set your timer for 15 minutes.

When 15 minutes is up, move the stock pot to a sink or other container filled with ice and water and then add one gallon of cold water. When the temperature falls below 80° F, transfer the Wort to the fermenter and add the yeast.

Bottle after fermentation has stopped.

The Numbers:

1.048 OG

1.011 FG

4.9% ABV

Justinian has been home brewing since he got a home brew kit for Christmas a month before his 21st birthday. He brews up websites almost as often as beer and his currently playing around with www.onehourbrewday.com. He lives in Colorado with his wife, daughter and two dogs.

How to Brew beer in an hour (or less) was originally published on HomeBrewTalk.com

0 notes

Text

Malt Experiment for a Black IPA — Blackprinz vs Midnight Wheat

Being a fan of hoppy beers, I’ve tasted a lot of different expressions of IPA, IIPA, Session IPA, and in it sboom, the specialty IPA’s like White IPA, Red IPA, Rye IPA and, one of my favorites of that list, Black IPA

or Cascadian Dark Ale.

This style, according to the BJCP Guidelines, was popularized in the early-mid 2000s. It was a style that boomed (like now the NEIPA) and every brewery was creating some batches of those and selling them like hot bread. Suddenly, the style started to go down in the national numbers, until it was just turned into a seasonal beer with a very well planned volume, so it wouldn’t go to waste.

In Mexico City, you cannot find a very good example of the style, because the style never was popularized like in the USA. If you could find a bottle coming from there, it wasn’t fresh because of all importation logistics and the hops were a little subdued. Being a style that wasn’t available, I tried to brew one just for me with a lot of hoppiness in there, resulting in a very enjoyable brew. I’m not such a fan of stouts, porters or very roasty beers. Nevertheless, Black IPA was delicious because the toastiness was restrained and it was just a faint touch of it, with a smooth, not astringent, nor bitter finish (this is part of the BJCP Guidelines).

I recently found that a supplier brought some Briess Specialty Malts and in hiding in between different bags, there were some Blackprinz (a hulless black malt) and Midnight Wheat (black wheat). I was wondering about the main difference between them, aside from one being wheat and other barley, and ended visiting the Briess website and made some research. Both malts have a quite similar description of lending a smooth, not dry, not bitter, not astringent flavor; and both are recommended for Black IPA. It was after reading the specifications that I decided it was time to test both malts in this nice and rarely

found beer style.

Grains Hop Schedule Yeast 83% – Pilsen Malt 50 IBUs Chinook @ 60min Nottingham Ale Yeast 6.7% – Crystal 40 Malt 17 IBUs First Gold @ 5 min 6.7% – BlackPrinz / Midnight Wheat 1oz First Gold @ 0 min 3.6% – Victory Malt 2oz / 2.5 Gallon First Gold – 3 Days

Notes: OG: 1.062 | 6.2% ABV

IBUs: 67

Mash Temp 149F – 90 Min.

Water Profile: Ca: 66 | Mg: 12 | Na:23 | SO4: 119 | Cl: 52

Black IPA Malt Comparison Process

On brew day, I decided to brew 2 little batches of 5 liters, just for sake of experimentation (and depending on the result, brew a bigger one for the kegerator sake!), with 30 minutes apart between batches for a stress-free day. I milled the grains, each batch with the respectively dark malt. Then, did a BIAB (Brewing in a Bag) with a classic approach:

Mashing for 90 minutes at 149 °F for a nice starch conversion and a lot of simple sugars. I added some Gypsum, Calcium Chloride, Epsom Salts and Phosphoric acid to achieve a nice 5.5 pH.

Boiling for 60 minutes with the respective hop additions.

Chilling with a copper immersion chiller.

With the 2 different worts, I took density measurements and reached the same gravity. Transferred them to 2 little PET carboys, rehydrated the yeast, pitched and put on some airlocks. Fermentation kicked up 8 hours, first in the Midnight wheat and just a little later in the Blackprinz sample, both with a lot of activity and a delicious aroma. After primary fermentation was over and gravity was steady, I added the hops in some mesh bags and waited for 3 days.

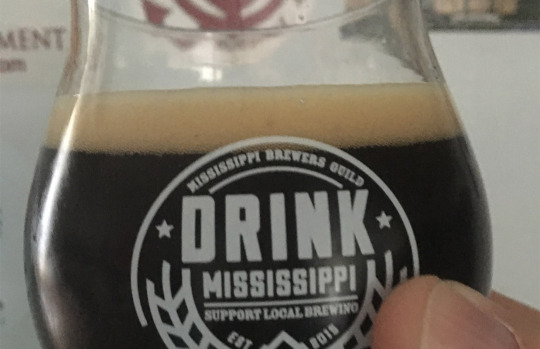

After dry hopping, it was time to bottle them, with some priming (sucrose) and waited for 10 days for the beer to be fully carbed. Finally, it was time to taste them and compare them! The approach was like the pro’s so an Appearance, Aroma and Flavor test was held with each beer:

Blackprinz :

Aroma: A lot of hops with a fruity profile, citrus with a slight hint of roasty character just behind the hops.

Appearance: jet black, opaque, with a head that slowly disappeared.

Flavor: hop forward, high bitterness, citrusy with a note of dark chocolate. Like eating a chocolate of 90% cacao.

Midnight Wheat:

Aroma: A lot of hops with a fruity profile, citrus with a lesser hint of roasty character than Blackprinz malt, just behind the hops.

Appearance: jet black, opaque, with a head that slowly disappeared.

Flavor: hop forward, high bitterness, citrusy with a note of dark chocolate but less apparent than with Blackprinz malt. Not sweet, dry, a little harsher than Blackprinz malt.

Conclusions and Discussion

When tasting them blindly, I couldn’t find a strong difference. Just after knowing each one and really paying attention to every detail in the aftertaste I could find a little more flavor in the Blackprinz pint.

It was definitely an IPA with an accentuated bitterness, but with an interesting back note of what I could say is roasted cacao. It really gives extra depth and complexity to the beer without being overpowering and cloying. I think Blackprinz and Midnight wheat can be substituted but IMHO, to accomplish a similar flavor profile (like that note of dark chocolate), Midnight wheat should be added in more quantities.

Midnight wheat is definitely a great choice to add color without almost any flavor, in that case, someone searching for just a black coloring while keeping the same flavor as a pale IPA can find a good ally in that malt. In the other hand, Blackprinz is also a good option to fix color but expect just a little more flavor.

by Hideki Arao

Hi everyone! I started brewing in 2013 as a hombrewer and then, after winning a medal at one of the greatest beer contests in Mexico, I started learning and studying more and more about beer. Right now I am the owner and brewer of a micro-brewery in the heart of Mexico City, pursuing the dream of being one of the best and innovative breweries of the region (you can check out our site http://beerproject.mx). Brewing, drinking, sharing and dreaming about beer,that’s the summary of my life!

Want to Read More About Experimenting? Check Out This Article »

Kits are a staple of the homebrewing scene. Put together by your local homebrew shop or the big online retailers, they are all-in-one boxes that give you everything you need to create beers that are time-tested and brewer-approved. Sometimes they are clones of popular craft brews, other times they are retailer exclusives that recreate classic styles, but either way they take the guesswork out of making a great beer. For both newbie homebrewers and veterans alike, that can be a very welcome thing indeed. But sometimes you want to throw a little twist into an old favorite. Sometimes you want to get creative but don’t know where to start. Sometimes you have a beer idea in mind, but don’t want to spend ages tinkering with a base recipe before you start introducing more unusual elements. That’s when you start kitbashing…

Malt Experiment for a Black IPA — Blackprinz vs Midnight Wheat was originally published on HomeBrewTalk.com

0 notes

Text

How to Brew A Crowd Pleaser

We have all been there. There is an event coming up that you want, or have been asked, to brew a beer for, and you want to brew up something that sets itself apart from the light lagers that so many are fond of while remaining accessible to those same light lager drinkers. It is a delicate balance, but with some forethought, you can brew an ale that delights the palate of everyone at that next big event, regardless of what they normally drink.

What Makes an Ale a Crowd Pleaser?

Now, when we say a crowd pleaser, we know what we really mean; a beer that our macro-lager drinking friends and family will enjoy, while packing in character that craft beer drinkers will appreciate, striking a nice balance between the two. Aside from style, which we will get to in the next section, there are four main characteristics that make for a beer that will be loved by all.

Light – This is perhaps the most critical factor because one of the chief complaints about craft beer that I hear from BMC drinkers is that its mouthfeel is too heavy. You do not need your beer to be bone dry, but you should aim for your beer to be medium-bodied or lighter.

Refreshing – Imagine a beer that you would want to drink after mowing the lawn on a hot summer day, and that is how refreshing your beer should be. And nothing makes a beer more refreshing than being effervescent from higher than average levels of carbonation. 2.7 – 3.2 volumes of CO2 should be sufficient without over-carbonating your beer.

Low Hops – Your beer does not need to be devoid of hops, but to make the beer as accessible as possible to as many drinkers as possible, you should use a light hand when administering your hops. A light bittering charge followed by an equally light flavor charge. The way I think about hopping a beer like this is that the casual drinker should be able to taste the hops without being able to identify the flavor as coming from hops.

Low Alcohol – This is not a strict requirement, but if we are being honest, part of the draw of BMC is its session-able nature, and you can use that to your advantage in designing a crowd pleaser of an ale. Between that and the fact that session beers are becoming more and more popular among craft beer drinkers, it is hard to go wrong in keeping your beer in the neighborhood of 5% ABV or less.

Crowd Pleasing Beer Styles

We all know there are a multitude of styles to choose from, and many of them — too many to write about in this article — could theoretically be made into a crowd pleasing ale. However, there a few styles that lend themselves particularly well to pleasing crowds, and that is because of their inherent conformance to the above-mentioned characteristics. Here are some styles that work well as crowd pleasing ales:

Blonde – Just about anyone who likes beer will drink a blonde ale. A great style to choose when you want to maximize your chances of success, while having a bit of latitude to add some character.

Kölsch – This choice is a bit bolder, but still very doable. I brewed a Kölsch for my brother’s wedding, and it was a resounding success despite the extra punch of flavor Kölsch yeast imparts to the beer.

Cream Ale – Another solid choice that is hard to go wrong with. This style is about the closest you are going to get to BMC without dipping down into lager territory. While you are, of course, not bound by the style guidelines in home brewing, if you are going to stay true to style, this one has the least amount of wiggle room in terms of adding character.

American Wheat – I like doing this style as a crowd pleaser because you get a beer that is akin to a German hefeweizen, just without all the banana and clove yeast character that is likely to scare off non-craft beer drinkers.

As I said, this list is far from exhaustive, but for your first foray into brewing for the widest audience possible, these are the styles that I feel you are most likely to have success with.

Technical Considerations

Now, for the fun part! How do we actually design our recipes to achieve the characteristics listed above? There are several technical considerations that go into designing a recipe for a crowd pleasing ale, and while they are all fairly straightforward taken individually, getting them to play well together in a way that will tickle anyone’s taste buds is the true art of brewing a crowd pleasing ale.

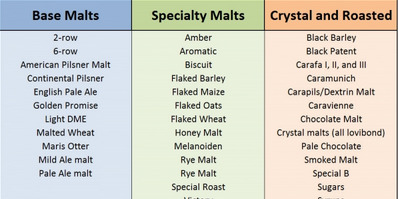

Grain Selection – Depending on the crowd you are trying to please, bold flavors may be appropriate, but for the purposes of this article, we are trying to brew for the widest audience possible, so that means light grains are the theme of the day. Feel free to experiment, of course, but in my own brewing, I have found that the lighter in color the beer, the more likely the non-craft drinking public are to enjoy your beer. That is why I generally stick to the lightest grains, and add character by adjusting other parts of the recipe. Here are some staple grains that I use when brewing a beer that anyone can drink:

Pilsner

Pale Ale

American 2-row

Marris Otter

Golden Promise

Amount of Grain – In keeping with the goal of staying under 5% ABV in your beer, you are not going to be using a whole lot of grain. It is going to vary, of course, based on the efficiency of your system, and the exact grains you use, but generally you will not be using any more than 10 pounds of grain for a five gallon batch at 75% brew house efficiency, which is how my system performs.

Mash Temperature – To achieve the light to medium body that we are looking for, we need to keep our mash temperature low, but not so low that it results in a bone dry beer. Without getting into the science behind mash temperature (to which I could devote an entire article), the basic principle is that lower mash temperatures result in a wort with more fermentable sugar than the same mash at a higher temperature. Thus, a higher mash temperature will result in a beer with more body, which we are not looking for here. The ideal mash temperature range to achieve the body we are after, in my experience, is 149 – 153 F (65 – 67.2 C).

Hopping Schedule – We are keeping our hop character low for these beers. Remember, to the casual drinker, the hops should be detectable, but not identifiable as hops. You are going to want a small bittering charge to balance the low malt sweetness, and then a small flavor charge to add a bit of hop character without being overpowering. You generally want to choose hops on the lower end of the alpha acid scale so that if you accidentally use too much, it won’t affect the beer as much as a higher alpha acid hop variety. Which hop varieties you use is up to you, but in in general, the safer option is to avoid the fruitier hops. However, given the sheer number of hop varieties, and their associated characteristics, experimentation will often lead to some amazing beers that still please a wide variety of palates.

Yeast – This part of the recipe is easy, but worth mentioning for completeness’s sake. Any clean fermenting, medium to high attenuating yeast strain will do very well, such as California Ale, American Ale, US-05, or Kölsch (if you decide to brew a Kölsch). Again, feel free to experiment because you can turn a run-of-the-mill beer into a great, yet still crowd pleasing, beer just by changing the yeast to one that throws some esters and adds a little extra depth.

Example Recipes Sure to Be a Crowd Pleaser

Here are two recipes of my own that saw great success and high praise from even the most staunchly anti-craft beer drinkers I know. The first one is a blonde ale recipe that I designed for the brewery that I am co-founding, which got rave reviews at our first tasting event open to the general public. The second one is the Kölsch that I brewed for my brother’s wedding some years ago that even my Bud Light-for-life aunt enjoyed. I would love to hear from anyone who brews these, or any other recipe based off of the information in this article, and whether they were successful in pleasing your particular crowd. Cheers!

Scuttlebutt Blonde Ale (5-gallon, 75% Efficiency)

Mash Temperature – 152 F (66.7 C)

Grains Hop Schedule Yeast 10 Lbs – American 2 Row 0.75oz Cascade @ 60min Safale S-05 1oz Cascade @ 10 min

Notes:Ferment at 68F, carbonate to 2.7 volumes.

Goldilocks Kölsch (5-gallon, 75% efficiency)

Mash Temperature – 152 F (66.7 C)

Grains Hop Schedule Yeast 9 Lbs – German Pale Ale Malt 1oz Czech Saaz @ 60min WYeast 2565 – Kolsch Yeast 1oz Czech Saaz @ 20 min

Notes:Ferment at 65F, carbonate to 3 volumes.

by Aaron Lott

Aaron started brewing while he was in the U.S. Navy, and has been home brewing for more than nine years. He is currently in the process of turning his passion for brewing into a career by starting his own brewery near Houston, TX. He lives in Houston where he goes to law school at Thurgood Marshall School of Law.

Want to Read More About Recipe Formulation? Check Out This Article »

After most of us have a few brew days behind us, and possibly a few beers in our belly, we get the bright idea that we can make a stellar recipe…on our first try. As I like to say, “Even a blind squirrel finds a nut once in awhile.” However, chances are that squirrel is not you!I remember my first recipe – a southern English brown ale. I looked at the BJCP guidelines for 11B and saw there was a large emphasis on the “sweetness” in this style. I proceed to throw over 2-lbs of crystal 60L malt in that five gallon recipe and used very little hops which contributed to a low bitterness. A few weeks later my taste buds received a thorough lesson on the definition of a cloyingly sweet beer…

How to Brew A Crowd Pleaser was originally published on HomeBrewTalk.com

0 notes

Text

Finally! New Brewing System That Can Brew A Single Pint of Homebrew

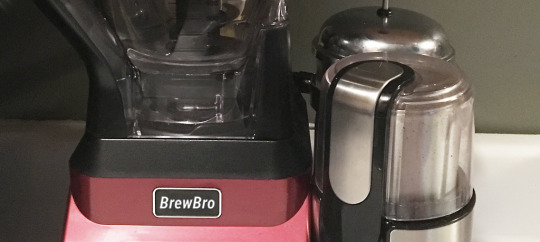

The world of automated brewing systems has exploded since the launch of the Pico Brew in 2013, automated brewing systems have been popping up like fruit flies in a house made out of bananas. Some big name examples like the BeerDroid / BeerFlo, the MiniBrew, IGulu, the Brewie and all the variations of the Pico line. However, there was one system that really caught my attention for a few reasons. It’s called the BrewBro and it brews a single pint of beer at a time.

What makes this brewing system unique, unlike the others previously listed, is that it brews a single pint of beer at a time. Founder, Ted Bronson, gave us a first-hand look at the BrewBro.

Ted Bronson on the BrewBro Brewing System

The BrewBro is a revolutionary brewing system that we’re launching in April of 2018. What makes this system so groundbreaking is 3 factors. First, it has three phase fermentation. This means that you have your standard fermentation, a secondary fermentation, and an optional third phase; cold lagering. Second, a revolutionary process we call active oxygenation. We know how important it is that your beer gets lots of oxygen throughout the entire brewing process. Our system infuses oxygen into the fermenting beer all the way from the yeast pitch to bottling. Lastly, it brews a single pint of beer.

Sometimes, you don’t want 1, or 3 or 5 gallons. Sometimes you just want a single beer, you know? So that’s why we made this system. So I can hone my craft to brewing the perfect pint… literally.

How the BrewBro Works

The main vessel is where the brewing magic happens. Add uncrushed grain to the top of the tower. The system handles the rest. First it crushes the grain with it’s NinjaBladeTM tech. It ensures that each kernel is split perfectly down the middle. This guarantees between 25-30% efficiency. The center of the tower is the heating element which boils the grains and wort to make sure you get the maximum flavor in your pint of beer. Next, the beer gets transferred through the oxygenator, and then into the fermenter cup. As fermentation begins, CO2 is forced out of a valve. The negative pressure sucks air through a hepa filter, creating the ongoing oxygenation of your beer.

How Can I Get a BrewBro Brewing System of My Own?

BrewBro is launching on April 1st, 2018 for the early-bird price if $3895.00. Pretty reasonable as the final price will be just shy of $5000. If you’re interested in spending just as much time brewing 1/50th of the beer in a standard batch, the BrewBro is for you.

” Sometimes you just want a single beer, you know? So that’s why we made this system. So I can hone my craft to brewing the perfect pint… literally.”

It may sound like a major investment, but when you see how the finished beer comes out, Myself and Ted agree that you’ll be brewing your own single pints of beer in no time! You can order your BrewBro brewing system at www.homebrewtalk.com/AprilFools.html

by David “Marshmallow Blue” Doucette

David is a full blown fermentation enthusiast who has dedicated much of his free time to learning and sharing the art of homebrewing. He’s spent several years documenting and writing homebrewing information on his blog Hive Mind Mead. He’s written over 60 articles between Homebrew Talk and Homebrew Supply. He also writes for his own homebrewing blog, Hivemind Mead

Trick Your Friends With These Other Great April Fools HBT Articles:

New Bill Could Allow Homebrewers ot Sell Homebrew on Cottage Licenses

Study Shows Isomerized Alpha Acids can Increase Your IQ

Brew Your Own Glow in the Dark Beer!

Finally! New Brewing System That Can Brew A Single Pint of Homebrew was originally published on HomeBrewTalk.com

0 notes

Text

Brewing Big Batches: Implications & Troubleshooting

When I started the hobby and made some research about recipes, equipment and raw materials, I found that almost everything was in some kind of codified volume : 5 gallons. The recipes I found were for 5 gallons of beer with their respective amount of grains, hop additions and yeast. The equipment was mysteriously listed for 5 gallons, like the carboys, the coolers for the mashing and the fermenters. I thought it was a holy number and always followed the instructions: everything for 5 gallons.

Then the time came where I could start buying new equipment and found a boil kettle that was 9 gallons. I thought it was weird, because everything I had was 5 gallons and those 4 extra gals were for more free space and to avoid boil overs (the addition of hops when the wort is boiling and you don’t have some space in the kettle is a headache). After that, I started tweaking around the recipe, the efficiency of the system and realized that I could tweak another variable: the final volume. I worked the recipe as a mathematical equation: if you have X of 2 row malt, then 1.84x (scaling from 5 to 9 gallons for 8 gals of beer) must do the trick. I made the same with the water, hops and yeast. Hell, I was wrong…

On brew day, everything went wrong: the tun was so full of water and grains that I had to drain some water liquid, there was a stuck mash, and the Original Gravity (OG) of the wort was too low, and the bitterness higher than expected. That was the time I realized that brewing larger batches wasn’t just as straightforward as I thought. When brewing more than 5 gallons, there are some variables, which are correlated, that must be taken in account:

1. Capacity of the equipment (Mash Tun, Boiling Kettle and fermenter).

2. Efficiency that can be achieved with the system.

3. Expected OG.

Understanding these variables will guide the brewer to know how many malt and hops must use be used to achieve X Original Gravity with a Y efficiency. Let’s go deeper into each one of the points:

Capacity of the Equipment for Big Batches

It’s important to know how much volume the tuns can hold. It’s easy to lose track of the fact that water and grains can impact the total volume of the mashing. If the mash tun capacity is of 7 gals, the brewer can’t expect to be capable of mash 7 gals of water mixed with grains. The grains will occupy space and, if not taken in account, there will be a flood at the moment of the dough in. There are mathematics ways to calculate these volume of water + grains, but, thanks to the technology, we have brewing software , which can help you the brewer out to know how much capacity the brewer tuns must have in order to brew X volume of beer.

The Boiling Kettle capacity is important too. If it fits the exact volume of wort, there will be some spilled liquid by the vigorous boil and a 100% guarantee that there will be a boil over when adding the hops or boiling off the hot break (there is a reaction when adding hop pellets that a lot of foam is created and everything starts to flood. This can be countered by a water sprayer to “destroy” the foam, but it is a headache the that most brewers want to avoid.)

Finally, the fermenter. If the fermenter is the exact volume of the wort coming in, there will be a 100% assurance that there will be a mess when the fermentation starts. Yeast will start to devour the sugar and a Krausen will form (a foam of proteins, hops and yeast). If the brewer is not armed with a blow off tube, the airlock can be clogged by the Krausen resulting in pressure building up. If it’s not handled, the fermenter can just launch the airlock out. Beer and yeast will be in all over the place. Changing the airlock is a headache because it has to be done several times until fermentation is less vigorous and the contamination hazard is very high when doing this. The correct way to counter attack this is to build a blow off tube that let the Krausen flow from the fermenter to a bucket/bottle with some sanitizing solution; or have a fermenter with more capacity (20% is recommended).

Big Batches & Efficiency

When brewing a high volume of beer, the brewer must take in account that the efficiency that he/she is used to while brewing 5 gals of beer is going to change. This is often related to a more compact mash (less water to grain ratio) that gives less space for the malts to interact with the water and covert the whole starch (enzymatic activity), or even related to the difficulties to mix the mash with all the extra grains (easier to mix 10 pounds of grain than 30 pounds). This variable is not as easy to predict as the other ones, like having some extra space in the mash tun or boiling kettle just in case. The only way to discover the new efficiency is by brewing. This uncertainty is awful at the beginning, but it’s the only way to understand it. Here’s an example:

The brewer is used to have a 70% efficiency when brewing 5 gals, and expect a wort of 1.05 points of gravity. The brewer uses the same malts and just scales the recipe x3 (moving from 5 gals to 15 gals). At the end of the brew of 15 gals, the brewer achieves a wort of 1.045. This means that there is a drop of 7% in efficiency. An adjustment must be done in order to counter this by:

1.- Adding more malt or extract (Dried/Liquid Malt Extract).

2.- Incorporating extra steps in the brew, like a fly sparge or mixing the mash more often. Or…

3.- Choosing a different method of mashing, like changing from BIAB (brewing in a bag) to a false bottom mash tun to be able to do a sparging/lautering.

There’s another option but it is not recommended. This is milling the grains with less space between the rollers, giving a finer grist. This actually elevates the efficiency, but at the cost of a latent danger of a stuck mash because of all the flour created. This can be avoided if you’re using the brew in a bag method.

Another thing to consider is the heat retention of your mash and strike water. The larger the volume of your mash, the slower it will lose temperature. This also means that 170F strike water in a 5 gallon mash may be too hot for a 10 gallon mash, resulting in a correction being needed or a high mash temperature.

With Big Batches, and Standard Size Batches, Everything is Connected

In brewing everything is connected and we can have a “butterfly effect”. A lower gravity from the lower efficiency in the mash, can cause the wort after the boiling to be more bitter (utilization of hops is higher with less sugars dissolved), ending in the worst case in a beer quite different than expected. Even stuff like the gas/electricity that is going to be used to bring the wort to boil and the time extension to chill it has an impact that is important to take in account while scaling.

Knowing the efficiency and implications of the new system can be challenging and time consuming but it will give the brewer the freedom to brew larger batches of beer with certainty in the numbers, which can be translated into certainty of the resulting beer.

by Hideki Arao

Hi everyone! I started brewing in 2013 as a hombrewer and then, after winning a medal at one of the greatest beer contests in Mexico, I started learning and studying more and more about beer. Right now I am the owner and brewer of a micro-brewery in the heart of Mexico City, pursuing the dream of being one of the best and innovative breweries of the region (you can check out our site http://beerproject.mx). Brewing, drinking, sharing and dreaming about beer,that’s the summary of my life!

Want to Read More About Big Batches? Check Out This Article »

A brew size of around 200 liters therefore seemed about right to start with and could be fitted into a small-purpose built (3.5m x 4.0m) brewhouse in my garden. Getting the structure built was relatively easy using our regular Portuguese builder who is talented at making new features, additions, and extensions in a way that captures our traditional property architecture. For the kit, I wanted to replicate large-scale breweries as much as possible, rather than settle on home brew adapted buckets and pots. This meant going for purpose-built, stainless-steel vessels throughout. BrewBuilder in the UK supplied me with a 200-litre hot liquor tank (HLT), mash tun, and boiler, together with two 100-litre …

Brewing Big Batches: Implications & Troubleshooting was originally published on HomeBrewTalk.com

0 notes

Text

Three Areas of Consideration When Expanding Your Home Brewery.

Are you totally obsessed with brewing? Are you ready to expand your homebrew operation past the beginner stages? In that case, you’ll want to seriously consider three areas of your procedure: milling, fermenting and bottling.

Expanding Your Home Brewery: Milling

A grain mill is one piece of equipment that could last us the rest of our brewing careers, so it’s useful to purchase the best possible product to suit our needs. Let’s start by discussing the fact that we cannot mill grain perfectly without the proper piece of machinery. We can attempt to crush the kernels by blending, smacking them with a wine bottle, crushing with a rolling pin or pounding them in a mortar and pestle, but the result will be disappointing. If the kernels are too thoroughly smashed, there could be a large amount of powder in our grain bed, which can lead to a stuck sparge. If the kernels aren’t crushed enough, our efficiency will fall dramatically.

There are two main decisions when selecting a grain mill. You can purchase a mill that crushes the grain with rollers, or a mill that crushes the grain with grinding pads. The roller method is the most precise method for milling barley as it squeezes the kernel in between two rods before dropping the kernel into a container below. One important thing to look for in a grain mill with rollers is the adjustability of the crushing gap. The more adjustable the rollers, the more useful the grain mill will be in the long run. Remember that you’re buying a product to last you as many years as possible, so consider the fact that you might want to brew with specialty grains in the future that require a different grind to barley so that the adjustability will come in handy.

Roller grain mills will come with two or three rollers. The two roller models are perfectly fine, but the third roller ensures you get a more thorough crush the first time through. Most three-roller models will press the grain initially and then push the kernel to a second station for a more comprehensive crush. This means that you could achieve a similar outcome by crushing grain twice in a two-roller model, but it takes twice as long. The decision is yours.

Grain mills that grind grains between two pads are less reliable and not necessarily as precise, but they have one huge benefit; they’re cheap. The motion of moving the grains between two rough pads is naturally more haphazard than pressing the kernels between rollers, but both methods work. Do yourself a favour and read through some online discussions on grain mills. You’ll find that most people are very happy with the model they have, simply because it is particularly effective or because it gets a rough job done for a low cost.

Of course, you’ll want to make sure you read a thousand reviews of the specific model you’re planning on purchasing to make sure that the product is reliable. Also, consider speaking to the people at your local homebrew store to get some trustworthy advice.

Fermentation

When considering fermenting vessels you have three main options: A plastic bucket with an airlock, a plastic fermenter or a glass carboy. A plastic bucket with an airlock is basically a less expensive plastic fermenter. Both of these fermenters are almost always opaque, so you can’t see the progress of your brew, and both are easy to clean since the lid is very wide. Make sure any plastic you buy is food grade and remember that the surface may be easily scratched. Scratches will allow microorganisms to hide in the vessel after an improper clean, so be gentle. Since the plastic buckets require you to be particularly vigilant with sanitation, it’s probably a bad idea to put beer into a used container. The tub in which you mix your pool chlorine or take fishing is probably unsuitable for brewing, even if you’ve never caught a bream.

The plastic fermenter can be more useful if it has a spigot on the bottom, which can be fitted with a bottle filler (bottling rod) to make the final stages of fermentation easier. The purpose built plastic fermenter will also be easier to transport if it has handles since the people who designed it are expecting the vessel to carry over 5 gallons.

Finally, the glass carboy is the best for storing beer long term. If you’re lagering or souring a brew, or trying to infuse some additional flavor with a secondary fermentation stage, then the glass carboy is the most appropriate piece of equipment.

Be aware though, the top of a glass carboy will be very narrow, so sanitation will only be possible by flushing the vessel out and soaking or rinsing with sanitize. Glass is also less malleable, so you won’t be able to install a tap at the bottom; you’ll need a siphon to transfer the liquid properly. Oh, and DON’T DROP IT!

With all of these benefits and complications to individual products, the answer is simple; get them all. Purchase one of each of these fermenters and you’ll be able to keep multiple beers in separate stages of the brewing process. As you’re expanding your home brewing operation, an opportunity to triple the amount of beer you can brew is a prospect that shouldn’t be ignored.

Another factor of improvement in fermentation is to make sure you have some form of temperature control. This can be a converted fridge, or something like the BrewJacket Immersion. Controlling your fermentation temperature is huge as many yeast strains don’t really like being at 68F and prefer the lower to mid 60s. Temp control also opens up the ability to brew lagers, which allows you to brew dozens of new styles.

Bottling

Now we’re on to bottling. Guess what: just like milling and fermenting equipment, you’ll get what you pay for with bottling gear. You could buy a hand capper for a few bucks and expect to simply refill the empty bottles your mates left at your house last weekend, but when those three fermenters we just spoke about are ready for bottling and you need to get 15 gallons into two hundred little glass vessels, you’ll wish you were more prepared.

We won’t discus kegging in this article because it’s probably a little too much for us at this stage. If we’re considering milling gear and fermenters, lets focus on that for now and deal with ball lock systems and aluminium cylinders and in a few months.

We can select glass bottles or plastic bottles. Glass bottles need to be capped, plastic bottles use screw on lids. Glass is better for aging beer, plastic is better if you plan on drinking as much of this brew as you can fit in your belly as soon as possible and there’s a moderate chance that you could drop a beer at some point in the evening. Of course, glass can be salvaged for free from your recycling bin.

Again we’re at a stage where each option comes with its benefits. Can you guess where we’re headed now? That’s right, lets plan to use glass and plastic. Since you need to purchase plastic PET bottles (if you don’t already have some), but they’re simple and practical to clean, prepare and re-use, consider keeping thirty or forty on hand. This way, you can quickly transfer a standard beer into bottles to be drunk soon, then cleaned and re-filled for the next time you want a quick brew. But, glass is much better for aging beers, so store your big beers and the darker stuff you’d like to leave in the bottle for a couple of months in glass.

Another consideration for the social home brewer is that glass makes for a better gift. If you bottle a six pack for a friend, you can give them glass without having to mention, “Can I please get those bottles back when you’re done, mate?” Now you’ll need a capper and, just like the grain mill, you get what you pay for. Luckily, even the best cappers aren’t particularly expensive, so you can purchase something that will attach to a workbench and last you for a long, long time for a very reasonable price.

Having enough bottles handy when you need them might also require a little planning, so consider hoarding all the bottles from a celebration. Maybe Christmas is just around the corner, or there’s a particularly rowdy barbeque coming up soon; either way, put a bin or a plastic bucket off to the side and tell everyone to throw the empties into it. You can soak the whole haul in sanitiser and figure out which bottles have the most forgiving packaging. You’ll find that some labels simply fall off and some need to be scraped away. With this in mind, avoid bottles with foil stickers. These things flake off and the metal shavings can get inside your other bottles.

So now you have a mill, three fermenters and a couple of bottling options for your separate needs, what’s next? What a stupid question, we all know what’s next; it’s time to make some beer.

by Daniel Norrish

Daniel is an Australian homebrewer, living on the west coast of the country. When he’s not boiling wort or waiting for brews to lager, he writes novels and watches rugby. Dan prefers strong, dark beers, but he’ll drink anything and he enjoys adding strange and peculiar flavors to beer.

Learn more about controlling »

Up until now you’ve been fermenting your beer in the basement, or in that hall closet that stays nice and cool. What if you want to brew a saison that calls for higher fermentation temperature, want to try your hand at lagering, or even dial in your standard ale fermentations more precisely? You need a way to control the fermentation temperature. Temperature control isn’t just for beers that ferment higher or lower than average. All of your batches can benefit from being at the right temperature at the right time…

Three Areas of Consideration When Expanding Your Home Brewery. was originally published on HomeBrewTalk.com

0 notes

Text

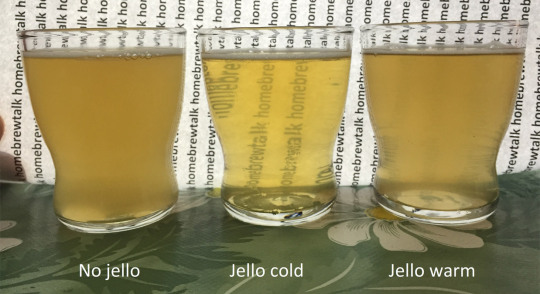

Gelatin Fining - Cold Versus Warm

In my last article about gelatin, I explained how it works (physically and chemically) and proved that a short boil does no harm to it, busting a common brewing myth. After multiple positive responses, I decided to do an experiment to bring more light into another commonly discussed, gelatin related topic: “Do you have to cold crash before gelatin fining?” While with the last topic, opinions were quite polarized, some people saying boiling gelatin is a disaster, others being on my side, with this one, most people agree cold crashing is recommended. Let’s look how much of a difference it really makes!

What Exactly is a Chill Haze?

Every homebrewer knows that sometimes, after putting a warm bottle of apparently clear beer into a refrigerator, the beer becomes hazy as it cools. Generally, some proteins are insoluble in beer, while others are soluble up to a certain concentration if certain conditions are met. The insoluble ones are not a problem, as most of them settle during whirlpool or during fermentation, however, temperature is the limiting condition for the soluble ones. Years ago, at school, we did an experiment, comparing salt solubility in cold vs hot water. I learned, that in hot water, the solubility of table salt is slightly higher than in cold water, but also that when I cool the hot sample, the extra salt “jumps” out of solution, which is called precipitation. The same happens to proteins in beer, forming the well-known chill haze. That is why lagers don’t get hazy. They are cleared (usually by filtering) at near freezing temperatures, so by cooling a bottle of lager to a serving temperature, you are still not reaching the chill haze point.

Hypotheses

Before making an experiment, I formulated a few hypotheses based on my limited knowledge of the problem.

The gelatin “waits” diluted in the warm beer and during chilling, the chill haze forms, gelatin “grabs” on it and clears the beer in the next 48 hours as usual.

The gelatin settles to the bottom of the warm bottle (taking the haze that is already present) and then, after chilling, the chill haze forms, but does not settle.

The gelatin somehow clears all the proteins even at the warm temperature, so no chill haze forms during chilling.

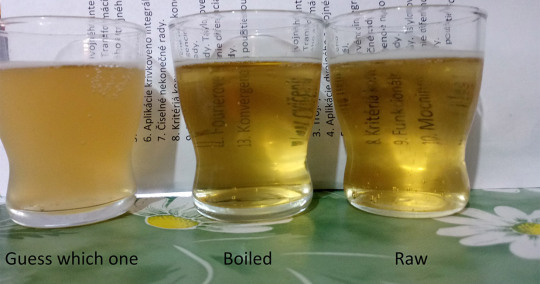

The Gelatin Experiment First Day:

The three samples of the same beer have been stored upright for 12 hours, one of them in the fridge, the other two warm. I took a photo to show you the chill haze, the warm ones were almost clear, despite being witbiers. I then injected one cold and one warm sample with the same amount of (boiled) gelatin, capped them and shook all three samples well. I returned the cold sample into my kegerator and the warm ones into my closet.

80 hours later: I took all three samples out for documentation. The difference was quite dramatic. The chilled sample, which was the haziest before, was almost clear, only showing a slight haze in the lower part of the bottle (the photo is not accurate here, probably due to artificial light). The untouched warm sample was now the haziest one. The warm sample with gelatin was interesting, because while it appears to be clear in the photos, with my bare eye I could see tiny but visible solid particles floating inside, equally distributed top to bottom, maybe 2mm apart. I have no hypothesis for this. It was, nevertheless, the clearest of the three with the best readability. After this documentation, all three samples were put into the kegerator.

20 hours later: Another quick check, just to see how the warm samples react to chilling. The untouched one was no surprise, but the (previously) warm one with gelatin was the same, impossible to even recognize anything behind the bottle.

48 hours later, The Judgement Day:

So here it is, the final results. You may argue that the cooled sample had more time to settle in the cold, and I agree the schedule I have chosen was probably not ideal, but it was hard to decide which one to choose. However, I adjusted to this by only making 0,75ml samples, so only the upper ¼ of the bottle ends up in the glass. From my experience with gelatin I know that beer drops crystal clear in 3-5 days in a half meter tall keg, sucking from the very bottom. Anyway, the results are obvious, the cold fined sample was crystal clear, the untouched one opaque and the warm fined one only slightly clearer, although I cannot comment on the floating particles as the beer was too hazy to see them. Taste-wise, the clear one was a bit crisper and somewhat juicier, while both of the hazy ones were a tad more velvety with fuller body, which I preferred with this particular beer style.

Conclusion

Unfortunately, it appears there is no way around it. Adding gelatin to warm beer might help with clarity very slightly, but I would not recommend it if you are planning to keg-fine anyway. If you are bottling directly after a warm primary or secondary, you might get a slight advantage at a cost of one extra fermentor opening (possibility of oxidation, infection). Decision is up to you.

by Robert Solarik

My name is Robert (but I like to call myself Robko). I was born, and I also live in Slovakia, a small country south of Poland. Ever since I was born, I have been curious how things work, which led to basically all my toys being disassembled at some point of their short lifespan. During high school times, however, I discovered the charm of homebrewing and after graduating, I was not really decided what university to proceed to. I don’t like doing things if I am not sure they make sense, so I got a job as a head-brewer in a small brewery, because that was my biggest passion at the time. After two successful years I finally decided for studies of mechatronics at a technical university in my hometown, and I am enjoying every bit of it. I am still brewing actively at home. It has been five years since I started.

Want to Read More About Cereal Adjuncts? Check Out This Article »

Many all-grain brewers seem to be put off when anything beyond a single infusion comes up in a recipe. Terms like “triple decoction” conjure up images of steampunk laboratories, mad scientists, and hump-backed henchman. Cereal mashing seems to get the same response, which is understandable as just about every article on the subject is filled with diastatic calculations, gelatinization temps, etc. which no one having a beer on brew day wants to remotely contend with…

Gelatin Fining – Cold Versus Warm was originally published on HomeBrewTalk.com

0 notes

Text

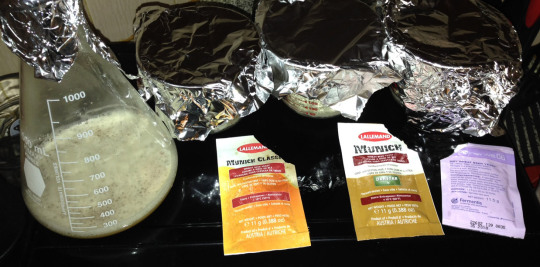

Hefeweizen Yeast Selection Experiment

One of the beers that made me enter the hobby of brewing was a nice and fluffy Paulaner hefe-eeissbier. It was the first hefeweizen I tasted and I fell in love instantly with the style: phenolic, estery, wheaty, refreshing, bubbly… simply delicious.

Since then I tried to brew some examples of the style, using the materials I had at hand; good wheat and barley malts, good German hops and some dried yeast (WB-06). It didn’t go well. The beer was crystal clear (an accidental kristallweizen?) and the classic banana and clove were very, very subtle. Not my favorite brew. Then I tried another yeast, Lallemand’s Munich. Same results. I live in Mexico City so liquid strains were hard to find. I was really frustrated because I was brewing nice blondes, American wheats, IPA, stouts and so on, but couldn’t brew my favorite style… Until I found a guy that could bring me a good vial of White Labs bavarian weisse Yeast (WLP 380).

I was so excited that the next day after I had in my hands the vial, I brew 5 gals of weissebier. Pitched the yeast (made an overbuild to save yeast for later, just in case it was a good yeast) and waited anxiously. On bottling day, I tasted it and I was in heaven, but it is quite different to a fully carbed beer. After 8 days, I open the first bottle and I had some tears in my eyes. Nice and delicious phenols and esters in the air, with a nice haze and persistent head… I finally brewed a decent hefe!

Then I found that my supplier was selling a new yeast from Lallemand: Munich Classic. I was like “hey wait… why is there a Munich and also a Munich Classic?”. I did some research on the Lallemand’s website and found that the description was changed for Munich Yeast, and Munich Classic had what seems to be a real hefeweizen description. So, I decided it was time to do an experiment with 4 different yeasts that are meant for the style and really compare them:

Hefeweizen Yeast Experiment Recipe

Grains Hop Schedule Yeast

2.8 lbs Pilsen Malt

6 lbs Wheat malt

1 lb Melanoiden malt

.5oz Perle @60

WB-06 Fermentis Yeast

Munich Lallemand Yeast

Munich Classic Lallemand Yeast

WLP 380 WhiteLabs Yeast

Notes: Ferment at 72F.

Process

2 days before, I prepared a starter for the WLP 380 yeast (3rd generation), so it was healthy and awake for the pitch. Then on brew day, I did a BIAB (Brewing in a Bag) with very classic methods. I Mashed for 75 minutes at 153 Fahrenheit. Boiled for 60 minutes and Chilled with my copper coil immersion chiller.

I separated the wort in 4 little carboys. I pitched the yeast but taking into account that for a “good hefe” one must stress the yeast.

No oxygen (for the dried yeast is not that critical).

10% less yeast than recommended for the pitch rate.

I did it for all the samples by weighing the dried yeast (and rehydrating them) and by checking the volume of the slurry for the liquid one. I also like to create something like an “open fermentor” so I just put a foil over the mouth of each sample, no airlocks this time. All where fermenting 12 hours after the pitch, except the one with the Classic Munich; but it caught up the other ones 4 hours later.

I waited 2 weeks for them to be fully attenuated and checked that the fermentation was over. They stayed in a room where the temperature doesn’t come below 72 °F. The odors, during fermentation, were different:

WB-06: just a little spicy.

Munich: quite neutral, like using an American strain.

Munich Classic: sweet banana.

WLP 380: mostly clove and then a lot of sulfur.

Does the aroma indicate that in each of the samples I will find the banana, clove or sulfur respectively?

After fermentation was over and it was time to bottle them (3.0 vols of CO2)

WB-06 / Munich / Munich Classic /WLP 380 respectively

After 2 weeks in the bottle, it was time to do a nice comparison like the pros: Aroma, Appearance, and Flavor. These are the results:

WB-06 / Munich / Munich Classic /WLP 380 respectively

WB-06 Fermentis Yeast

Aroma: A little fruitiness but not resembling banana nor bubblegum. Almost no clove, with a lot of yeasty, bready aroma.

Appearance: Quite hazy with a nice pale orange color, a head that was big at the beginning but disappeared after a minute.

Flavor: tart, a little fruity but not feeling the banana nor the clove, which are critical for the style. Not bitter just enough to balance the malts. Bready and grainy flavor with a silky mouthfeel, effervescent and dry finish, not sweet.

Munich Lallemand Yeast

Aroma: Quite neutral, like using an American strain. Bready, and yeasty aroma.

Appearance: Quite hazy with a nice pale orange color, a head that was big at the beginning but disappeared after a minute. Very similar to the Fermentis sample.

Flavor: A little tart, but overall very neutral with a very bold yeast and bready flavor. Banana and clove are nonexistent. Dry finish, not sweet.

Munich Classic

Aroma: Somehow sweet, banana and a little clove. These aromas disguise more the bready touch of the beer.

Appearance: Same than the other samples, hazy and pale orange with more retention.

Flavor: A little tart, not bitter, with some banana and some clove in there (more banana than clove). Esters and phenols are present and melt nicely with the grain bill, but somehow muted. Dry finish, not sweet at all.

WLP 380

Aroma: A lot of cloves, some apricot and a little sulfury note that disappeared after some minutes. Phenols cover the majority of the maltiness.

Appearance: Same than Munich Classic, good head retention, hazy and pale orange.

Flavor: Not tart at all, not bitter, not sweet, a lot of cloves, banana is minimal. Apricot is another note that lingers. Dry finish, silky mouthfeel and effervescent.

Results and Discussion

This is quite shocking because the wort was exactly the same, treated the same way, and the beers were totally different. You can find the following text in the respective websites of the brands:

Fermentis WB-06: A specialty yeast selected for wheat beer fermentations. The yeast produces subtle estery and phenol flavor notes typical of wheat beers. The choice of wheat or weizenbier fans.

Lallemand Munich: Munich Wheat Beer yeast originated in Bavaria, German and is a neutral strain which can be used to produce a wide variety of wheat-based beer styles. With only slight esters and phenol production, Munich’s allows brewers to showcase other spice additions. Traditional styles brewed with this yeast include but are not limited to American wheat, Belgian white, berliner weiss, gose, hefeweizen, dunkelweis, and weizenbock.

Lallemand Munich Classic: Munich Classic is a Bavarian wheat beer strain that can easily express the spicy and estery aroma profile typical to German wheat beer styles. This strain is simple to use over a wide range of recipe variations and fermentation conditions, making it a great choice for a number of traditional styles of wheat beer. In classic open fermentation vessels, the yeast can be skimmed off the top in the traditional manner. Styles brewed with Munich Classic include but are not limited to weizen/weissbier, dunkelweizen, and weizenbock.

White Lab’s WLP 380: High phenolic clove aroma and flavor, with minimal banana. Also produces refreshing citrus and apricot notes for a crisp, drinkable hefeweizen. Less flocculant than WLP300 and sulfur production is higher.

After tasting the samples and reading the description, I can say they are true, but not so much for the styles they are saying are suitable for. A hefeweizen is a yeast forward style with a solid malt backbone. I think that the Fermentis and Lallemand’s yeast does not have enough character for this style and create a quaffable wheat beer, but not a hefeweizen. In contrast, White Labs yeast create a nice mélange of phenols and malt components that approach very well the hefeweizen characteristics. My favorite of the 4 is, without a doubt, the WLP 380. There are a lot of forums and chats talking about some very specific temperature control, ones ramping each day to achieve an estery and phenolic profile from the Fermentis and Lallemand’s yeast. It can be true that with a more temperature focused process one can suck off the banana and clove of that yeast, but for this practical case where the fermentor is just sitting at 72 °F all the time, the yeast creating a very nice Hefe is White Labs.

by Hideki Arao

Hi everyone! I started brewing in 2013 as a hombrewer and then, after winning a medal at one of the greatest beer contests in Mexico, I started learning and studying more and more about beer. Right now I am the owner and brewer of a micro-brewery in the heart of Mexico City, pursuing the dream of being one of the best and innovative breweries of the region (you can check out our site http://beerproject.mx). Brewing, drinking, sharing and dreaming about beer,that’s the summary of my life!

Want to Read More About Experiments? Check Out This Article »

One of the very common rumors is that you mustn’t boil your gelatin solution (that many of us use as a clearing agent), because you DENATURE the proteins present and it no longer does its job. However, as everybody knows, it is a good idea to sanitize everything that touches the beer in its cold stage, so being able to boil the gelatin would really be convenient. This is the reason for me publishing this article, to bring (what seems to be) true to the masses.

Hefeweizen Yeast Selection Experiment was originally published on HomeBrewTalk.com

0 notes

Text

Making Carrot Wine

We’re in the depths of winter and folks might erroneously assume that fresh wine making produce was incontrovertibly thin on the ground. You’re invited to think again.

So, with the wine cellar in likely need of substantive input, where does that leave us with several idle months ahead before the dandelions even begin to display their splendid heads?

How about a canned pineapple wine? Fair enough. Maybe a couple of gallons of skeeter pee takes your fancy. Bottled lemon juice happens to be in the shops at this time of year. Then again, maybe not!

The winter vegetables are a somewhat prosaic candidate for experimentation, yet these uninspired items can nonetheless produce a wholesome wine. For no good reason they appear to somehow consistently languish at the bottom of the lower division and often fall below the radar when compared with homemade country wines derived from fruit. That is a shame because a well balanced and aged parsnip or marrow wine is definitely a tipple to savor if one has the patience to wait for the wine. Perhaps it’s the other way round: Will the wine have patience enough for those who seek to enjoy the fruits of their labors? Who knows?

Here’s a modern take on carrot wine that in the dark days of next year’s bleaker months could find a prospective home in a glass by a warming fire, preferably somewhere near you.

We’re looking to be able to fill eighteen bottles with star bright wine in six to eight months time, so allowing for wastage and the odd tasting the plan is to make 15lts.

You will need:

Sugars Spices Yeast & Other Ingredients

13 Pounds – fresh carrots

3 pints (48 fl oz) – orange juice

1 gallon – apple juice

1.3 pounds – sultanas

1 Pound – malted wheat

3 – lemons

1.25 cups – fruit syrup (rose hip is decidedly good) or grape juice concentrate

2.2 pounds – soft brown or Demerara sugar

1 – navel orange or pink grapefruit

1 – tbs malt extract

1 – liter active yeast starter

6 oz – root ginger;

4.25 cups – strong English breakfast tea (6-8 bags);

2 tbs – of coriander seeds;

1 tbs – each of broken cinnamon sticks, fennel and caraway seeds;

0.2 oz – ground turmeric (haldi);

1-2 g – pectic enzyme;

15 g – bentonite;

1 liter – active yeast starter

Brewing Your Carrot Wine

As basic wines go, the method is quite simple. Carrot wine is made in three stages just like any other. There are however, one or two unfamiliar quirks or exceptions to this idea. As you will see, there’s nothing neither complicated nor difficult to fathom. The required explanations are set out below, and we’ll cover the nitty-gritty of the finer details in the main body of the article. Until then; in a nutshell:

Prepare the must and pinch the yeast.

Ferment and rack off of the gross lees.

Ferment out the young wine. Rack again and age in bulk.

Pre-Fermentation

It’s a recommendation worth following to get the starter culture prepared twelve hours in advance of making the must. Use 1 tbs of sugar, 1 pint of orange juice and the malt extract topped up with boiling water. Cool to blood temperature; then add the yeast (slurry or dehydrated), to make what brewers call a small wort. Cover and set aside till needed. In the meantime, knock up a thin paste with the bentonite and set aside also.

Preparing all of the carrots sounds like a chore: It is. They should be scrubbed clean but don’t require peeling, if that’s any consolation. After being thinly sliced, poach the veggies with the remaining orange juice and just enough hot water to cover. Simmering the carrots until soft might take 30-40 minutes after coming to the boil. They mustn’t be over-cooked. In fact, there’s no need to do this as we have further plans for the al-dente carrots.

While the carrots gently simmer away par the zest from the lemons, grate the ginger, blitz in the magi-mixer or finely chop the sultanas, brew the tea in a liter of boiling apple juice and put all this into the sanitized primary fermentation vessel after adding the malted wheat. Add the syrup or fruit concentrate to the bucket and prepare to strain the carrots. Squeeze out the dregs from the teabags; rinse the bags in boiling water and pour into the fermenter.

Sooner or later, when ready, carefully strain the carrot water onto the other ingredients using a large colander. Best bet is to do this in batches. Transfer the cooked vegetables to a smaller bin and keep warm. Use a makeshift lid and towels to insulate the bucket.

Carrots contain little, if any, acid. This imbalance needs to be corrected. Juice the lemons and add to the must. Vigorously stir the must so as to fully aerate and combine everything together. The approximate ballpark figure for the initial specific gravity of the cooled must is 1060-1070º, or a potential alcohol content of 9.5% if fermented to dryness. When cool enough for the yeast, add the starter culture.

Carrot Wine Fermentation

Remember the pectic enzyme (pectinase) in the list of ingredients? This is where we part company with received wisdom because it doesn’t go into the must just yet.

On to a small point of clarification if readers will forgive the digressional pun. Pectinase destroys pectin: Any fruit that is known to contain sufficient levels of pectin so as to throw a stubborn haze in a finished wine needs the enzyme added in the early stages of fermentation. Be that the case, if incorporated, then a future problem has no future so to speak: nipped in the bud, as it were.

Whilst suspended solids are relatively easy to encouraged to drop (cold crashing at temperatures below 6ºC works well), a haze of colloidal pectin or starch in a near finished wine is a different order of difficulty to sort out when it comes to bottling time.

Pectinase is not a clearing agent in any sense of the term as most types of wine finings work in a fundamentally different way. Try adding the enzyme to a cloudy, pectin free wine. After a week or so the brew may have cleared somewhat, but that is simply due to the slowing down of active fermentation and settlement over time. You might incorrectly assume that the enzyme worked to clear the wine, but it had no affect what so ever.

Whether it’s purchase in a dropper bottle or as a dry powder, the enzyme works to degrade and destroy the hard glue-like inter-cellular substances found in fruit and vegetables that give rigidity and stiffness to the whole. The satisfyingly crisp firmness or ‘bite’ of an apple derives from the pectin.

Under the powerful liquefying action of the enzyme the sugary juices, fruit flavors and pleasing color compounds are released in a process called enzymic maceration.

Try the following technique rather than composting the cooked carrots.

Pour a liter or so of apple juice over the carrots and add the enzyme. Gently stir, cover the surface with cling film or similar to reduce oxidation and tidy the bucket away somewhere really warm (25-30ºC). After 24hrs strain the not insubstantial volume of juice off the solids using a grain bag. Squeeze gently to avoid an excess of pulp and from 6kg of carrots 4-5lts of juice can go into the primary fermenter alongside the rest of the now vigorously fermenting brew. Add the bentonite slurry. Stir well in. You should have 12lts or thereabouts of must by this point with a frothing fermentation on the go. Keep the fermentation on the cool side of 20ºC and stir the rising pulp back into the must twice a day for three to four days, at which point the gravity of the young wine requires adjustment.

In the presence of fermentable sugars and adequate nutrition, a thoroughly active yeast doesn’t mess about. Far from it. At an appropriate temperature, the yeast is perfectly happy to toil away while the going is good.

On day four, the must will show marked signs of separating into distinct layers as nutrition becomes depleted and fermentation stalls. The situation will begin to appear decidedly unfavorable for the yeast and it is now that an interventionist wine maker should step in and help the yeast to thrive in the face of deteriorating environmental conditions.

Now is the time to ‘sugar feed’ the young wine. Draw off 2lts of must into a large pan. Gently warm until the liquid can be heard, or as a foam rises. Add 500gm of the sugar and turn off the heat. Stir until the sugar is fully dissolved, add the turmeric, cover and allow to cool for thirty minutes. Rouse the whole brew and swirl in the feed. Each of these additions will raise the potential alcohol of 15 liters by 1.5%.

When the signs of a slow-down show themselves once again, repeat the procedure with the last of the sugar to leave a potential alcohol content of 14% or more.

If a sweeter finished wine is desirable then further sugar feeding will inevitably topple the yeast, depending on the environmental factors and the yeast strain being used, to leave a stable medium sweet wine of high alcohol content which conveniently suits the next stage of the recipe.

Stir in the final 2lts of apple juice. At this point lower the temperature to encourage sedimentation. When the wine is seen to deposit a heavy sediment and the SG. drops below 1010º it’s time to strain and press the solids into a secondary fermentation vessel or better still, an intermediate bucket for a twenty four hour rest period. After resting, rack off into three separate 5lt demijohns. From here-on in, proceedings should continue under an air lock.

Flavoring Your Carrot Wine