Text

Why are we so focused on what pronouns lesbians can use?

Why are we concerned about which LGBTQ person can use which slur in reclamation?

Why do we decide the passability of transgender individuals and whether or not they are “valid”?

Why tip-toe around politics of respect, when queerness in itself questions respectability?

Why have queer individuals begun to police the definition of queerness for each other?

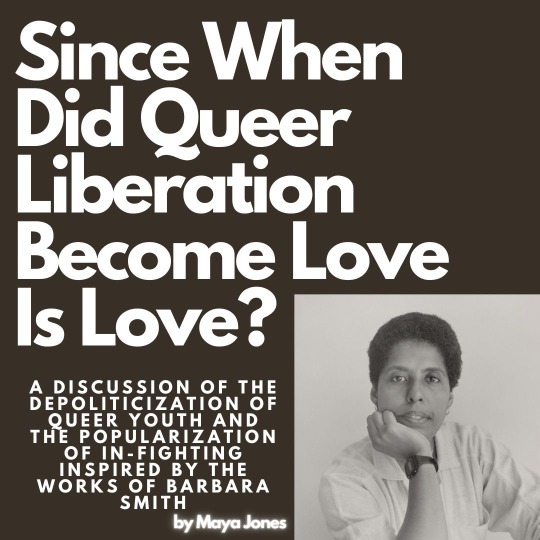

Since when did “queer liberation” become “love is love”?

Discourse is defined by Cambridge Dictionary as “discussion or debate” or a “formal or political argument”; this is the basis of the concept of queer discourse (Discourse, n.d.). When the LGBTQ community is pitted against each other in the debate regarding queer issues, division is created that imposes cisheteronormative and patriarchal beliefs in our community. This polarizing debate that causes division amongst queer youth tends to focus on widely debated topics such as neopronouns, gender roles in relationships, dysphoria, detransitioners, and countless others. These debates — referred to as queer discourse — commonly warp queer perspectives into being focused on inter-community disagreements instead of social change that can be made to better the livelihoods of LGBTQ youth and adults, such as transgender-affirming healthcare, protections against hate-based violence, LGBTQ-inclusive school policy, etc. Onenten is a nonprofit organization that shares the idea that the popularization of queer discourse is reductive and a step backward for the community. “This warped version of discourse aims to further divide an already fractured community. When large groups of LGBTQ+ publicly dismiss the validity of sub-categories that exist within our community, our focus is shifted from gaining total acceptance and liberation to infighting and identity-policing. This leaves vulnerable youth susceptible to indoctrination into exclusionary ideologies that pit them against members of their own community” (Swaffar, 2021). In light of the obsession that queer youth have developed towards discourse and identity politics, I think it is important to address the ongoing sense of apathy within spaces of young LGBTQ people toward revolutionary politics.

As Generation Z has lived through the legalization of gay marriage throughout the United States, many of this generation’s queer folks no longer see the inherent political stance that being queer takes. Furthermore, I think community values – such as solidarity between community members, unconditional support of transgender joy, and motivation to improve the world for the next generation of queer people to come, etc – have been lost. I believe this is a uniquely troublesome issue amongst Generation Z because many of us see the legalization of same-sex marriage to be the end goal of queer liberation, which is a false understanding of what it means to liberate a marginalized community. Brittanica defines the Gay Rights Movement as the movement advocating for equal rights of LGBTQ persons; eliminating sodomy laws and ending discriminatory practices in employment, credit, housing, public accommodations, and other areas are described as goals of the movement. The manifestation of this goal – the goal to create social, economic, and political equality for LGBTQ people – can be understood as queer liberation.

I believe controversy and discourse amongst young queer people have become reductive in a way that promotes patriarchal and cisheteronormative ideas instead of promoting queer liberation. In my research, I wish to explore this acquired sense of apathy that young generations of LGBTQ individuals have upheld since the 2010s and to dismantle this idea of respectability and apathy towards revolution that is so deeply ingrained in young queer people's politics.

I attribute much of the apathy within Generation Z’s queer community regarding radical politics to the popularization of respectability politics within the queer community. Respectability politics is a concept – described by Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham in her work Righteous Discontent – when marginalized individuals conform to societal expectations to garner better treatment from oppressive institutions (Higginbotham, 2003.) Imploring respectability politics in a queer context is to humanize LGBTQ people by creating an adjacency from cisheterosexuality to queerness. A prime example of the rise in respectability politics within the LGBTQ community is the popularization of the phrase “love is love”, as opposed to the sentiment of queer liberation. The strategy of employing the phrase “love is love” was to ask cisheterosexual people to see queer people's humanity because, underneath our queerness, we are all the same. I see this to be a falsehood. Equating the life and experiences of cisheterosexual individuals to that of queer individuals, due to our shared trait of being human, is to ignore the differences in our lives due to systemic oppression. We may share humanity, but we do not share experiences of oppression in the same way. To ignore our differences is to manipulate the cultural consciousness into believing that queer folks are simply the same as cisheterosexuals when we truly are both different in our lifestyles, values, culture, and inherent identities. These differences do not dictate that we should be treated differently, or with less respect; these differences are important and should be acknowledged instead of ignored. Ignoring our differences is to say “I don’t see color” and while that statement does not provide an exemption from negative racial implications, neither does “love is love” avoid any implications of homophobia and sexual orientation-based discrimination that may be expressed. The sentiment of love simply being love has been adopted by many since gay marriage has been legalized, and I believe this to be an acceptance of an unfair compromise given to us by the United States government to appease our desire for liberation. This acceptance only furthers the adoption of cisheteronormative ideals into the queer community, which explains why Generation Z has been weaponizing tradition against each other so often.

To give some historical background, a large obstacle for proponents of same-sex marriage legalization was the Defense Of Marriage Act (DOMA) in 1996, which federally defines marriage as being between one man and one woman. The purpose of the DOMA was to serve as a political and social statement that affirmed the traditional understanding of marriage as being between cisheterosexuals, reflected opposition towards the same-sex marriage movement, and sought to preserve the “sanctity of marriage” for heterosexual couples alone. The first state to legalize civil unions for same-sex couples was Vermont in the year 2000. Thirteen years later, the Supreme Court struck down a key provision of the DOMA in the United States V. Windsor, which granted federal recognition to same-sex marriages performed in the states in which it is legal. Two years later, in Obergefell V. Hodges, the Supreme Court ruled that same-sex marriage was a constitutional right and legalized it amongst all states nationwide.

Many queer scholars see the legalization of same-sex marriage as a compromise between the freedoms needed by queer individuals, and the freedoms that the American government was willing to give us. This compromise has been deemed reductive given the depoliticization that took place after the legalization of gay marriage has only furthered complacency from LGBTQ allies and apathy within the LGBTQ community towards our own liberation. This is not to diminish the importance of same-sex marriage legalization as a step towards legal rights for LGBTQ individuals but to stress the political implications of this decision. Conflating queer liberation and marriage equality is a false equivalency that devalues movements of social justice that seek to transform the oppressive institutions within society. Same-sex marriage was one step towards queer liberation, but to say as queer activists that we have met our goal is to misunderstand the systems of oppression that queer people live within. Many more issues exist beyond same-sex marriage for queer individuals. Access to healthcare for trans people, protections against discriminatory practices, legal protections against identity-based violence, and acknowledgment of queer history within the school curriculum: these are ongoing struggles faced by members of the LGBTQ community. To ignore the importance of these persistent issues is to settle for same-sex marriage. As a marginalized community with so much organizational power, and motive to advocate for universal freedoms, we should never settle for less than our freedom.

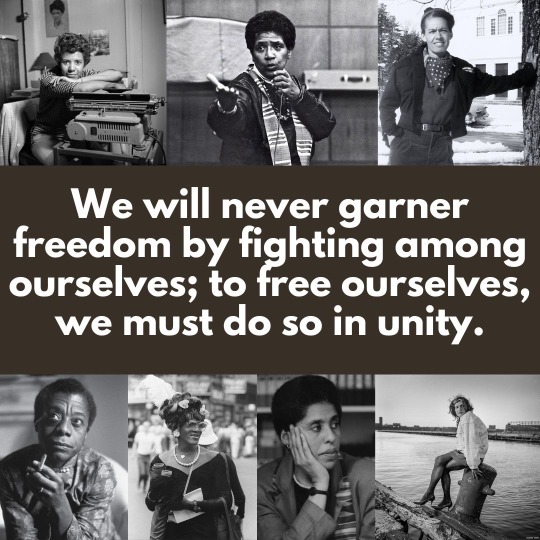

As many of Generation Z have been raised to think that same-sex marriage was the end-all-be-all of queer liberation, many folks within the community have lost their political consciousness and motivation for revolution. Instead, we focus on policing each other’s tone and identity, by discussing trivial and redundant points which have been repeated throughout the 2010s in online spaces. These conversations of slur discourse, respectability, and validity only create further division between LGBTQ young people, when we could be having conversations about how to better understand each other and fight for each other’s rights. Accepting the idea that we have achieved our goal for LGBTQ liberation gives queer young people the reductive idea that in-fighting is important when it only deters the movement. I believe this deterrence is strategically implemented by cisheteronormative society. As Barbara Smith, prolific queer scholar, states: “Given how well organized the Christian right is, and that one of its favorite tactics is pitting various oppressed groups against one another, it is past time for straight and gay activists to link issues and work together with respect.” (Smith, 1998.) To devalue our differences is only to devalue the importance of our unity, both within the LGBTQ community, and our cisheterosexual counterparts.

While this might seem like a new issue, there has always been in-fighting within the LGBTQ community from the beginning of the movement. As transgender women of color who experience marginalization beyond that of their white, cisgender counterparts, Marsha P. Johnson and Sylvia Rivera were changemakers and innovative activists at the forefront of the movement for gay and lesbian rights, they were not treated with the utmost respect within the community by people who did not identify as transgender themselves. Needless to say, the LGBTQ community is not united between all of the identities within the acronym, as these identities are unique to each individual. To assume all LGBTQ individuals understand and relate to the lived experiences of their fellow queer person is to assume a monolithic experience of queerness. Transgender individuals endure different systems of oppression than their cisgender, queer colleagues. Additionally, Black queer individuals experience intersecting systems of oppression that are different from the oppression white queer folks face. These differences in experience and marginalization, create diverse outlooks on queer discourse that often conflict. Cisheteronormative society often assumes queer individuals are all united in their values, which is a mistake that often leads to further separate us. Those of us within the community who don’t understand these differences ostracize folks who are further marginalized, this includes Black queer individuals, individuals of color in general, transgender individuals, and especially transgender women of color. This is reflected in the work, #HashtagActivism, which states that: “In fact, Sylvia Rivera, founding member of some of the first gay and trans liberation organizations in America, was once similarly booed and chastised for speaking to the concerns of trans women of color at a pride rally in 1973, only a few short years after her pivotal role in starting the LGBTQ movement.” (Jackson et al., 2020). This shows that the assumed solidarity between queer individuals is often not employed in the way that we need it. How can we achieve liberation if we don’t have each other’s backs? When heteronormative society places queer individuals in opposition to normalcy, we must seek solace among ourselves. As I see it, young queer people are not being taught to uphold this value of solidarity within the community, which only leads to further loneliness and isolation. We will never achieve liberation by refusing to look at our past. At the current moment, efforts are being made throughout the United States to censor school curriculums and protect children from learning about race, gender identity, and sexuality. Just since January 2021, forty-four states have taken steps to restrict the teaching of critical race theory or limit how teachers can discuss racism and sexism within their classrooms. Eighteen states have imposed these educational bans and restrictions either through legislation or other ways (Schwartz, 2021). In February 2021, a Florida committee advanced a bill that would restrict discussions of sexual orientation and gender identity in classrooms. More states since have followed in Florida’s footsteps in implementing restrictions on queer topics being discussed in school, which causes growing concern for the freedom of speech for queer youth within these schools (Thoreson, 2022). In light of this censorship, we must encourage our youth to be educated about social systems of oppression. We must look to our queer elders and queer scholars of the past to achieve the future which they desperately wanted for us. If we want the next generation of queer individuals to liberate themselves from this apathetic attitude towards revolution, we need to emphasize the importance of activism within the community instead of inter-community fights and puritanical ideas of conformity that queer discourse promotes.

As stated by Barbara Smith, “Gay rights are not enough for me, and I doubt that they’re enough for most of us. Frankly, I want the same thing now that I did thirty years ago when I joined the civil rights movement and twenty years ago when I joined the women’s movement, came out and felt more alive than I ever dreamed possible: freedom” (Smith, 1998). How will we achieve true freedom without acknowledging the differences in our love, lives, and oppression? Community values should always be of importance, but at the moment, they are hard to find. Discourse, online arguments, divisive propaganda, inter-community conflict, respectability politics, and tone policing are hindrances to LGBTQ liberation. We will never garner freedom by fighting among ourselves; to free ourselves, we must do so in unity.

#queer theory#queer discourse#generation z#respectability politics#queer liberation#love is love#solidarity#black lesbian

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

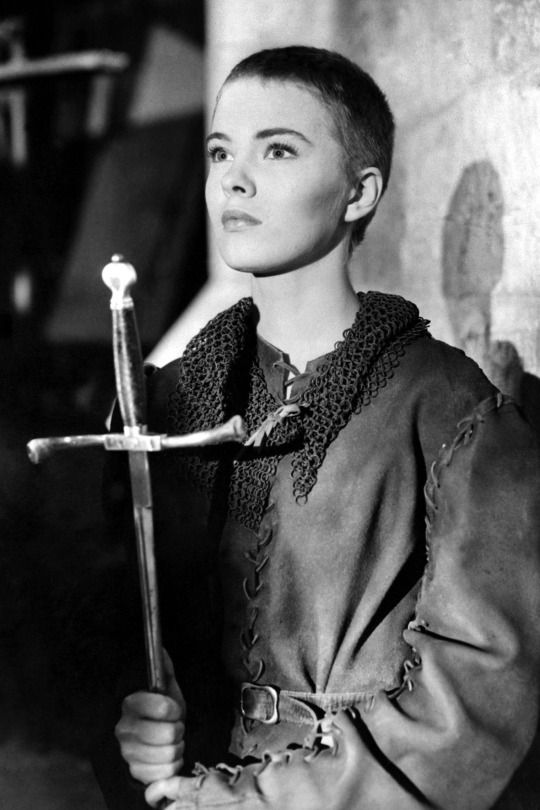

stage and film portrayals of joan of arc

condola rashad (saint joan, 2018) / renée jeanne falconetti (the passion of joan of arc, 1928) / jean seberg (saint joan, 1957) / ingrid bergman (joan of arc, 1948) / milla jovovich (the story of joan of arc, 1999) / diana sands (saint joan, 1967)

21K notes

·

View notes

Text

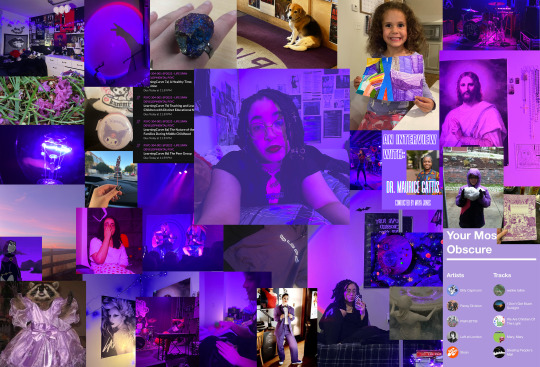

The Color Purple As A Motif For Black Femme Resiliance

I'm respoting my writing about the color purple here since I recently updated it for substack... feel free to subscribe :)

Historically, purple has been used to signify beauty, royalty, faith, prosperity, and healing, and the color symbolically has a strong connection to Black culture. Black Girlhood is the focus of this ethnography. As a young Black girl, my favorite color was purple, despite not knowing the historical and metaphorical connection my race has with the pigment. I later grew to love the film and novel The Color Purple by Alice Walker.

The Color Purple taught me that dignity, in being a Black woman, does not come from suppressing or hiding your authentic self. Being a victim of oppression is nothing to be ashamed of, if anything it shows resilience in survival. By relentlessly focusing on Black female stubbornness and resilience despite their vulnerability, The Color Purple disassembles the concept of the ‘strong/brave/loud/angry Black woman’. The story is a tale of the strife and resilience of a Black woman named Celie, who overcomes abuse and adversity and finds herself at the end of the novel with her children and a partnership with a woman whom she loves. This novel is a quintessential piece of Black lesbian media and I wanted to highlight it in my time capsule because the inherent resilience and strength of the Black lesbian woman deserves to shine in its bright purple light.

This collage is comprised of purple photos from my entire camera roll. The photos span from a photo of me as a child wearing purple, to selfies in purple lighting, to purple flowers I saw outside, to purple memes I found online, to a purple hi-lighted passage of a book. All of these photos have at least a splash of purple in them, and I recognize the symbolism of having so much purple surrounding me. Seeing the purple around me, I am reminded of my own resistance to white ideals and my resilience against white society’s oppression of Black women and gender-non-conforming people such as myself. I used these photos to emphasize the connection between purple as a motif for resilience and the livelihood of Black women/gender-nonconforming individuals.

As a Black lesbian gender-non-conforming woman, I have had to be resilient for a lot of my life under unfair and oppressive circumstances. As I see it, everyone who grew up as a young Black girl can testify to the psychological damage that is caused by living in the intersections of racial, sexual, and gender oppression. Going to a predominantly white school in North Carolina that was founded in “white flight” caused me to develop racial insecurities about being a young Black girl. Being raised with homophobic church doctrine caused me to develop religious guilt over my sexual and gender identity. Despite these hardships, all of this has taught me something throughout my life: While conformity — in some aspects — can be used as an important tool to survive, authenticity is imperative for me to thrive. A lot of my philosophy has to do with retribution for and reconnecting with my identity as a Black lesbian gender-non-conforming woman as well as being able to face God as my authentic self. In this authentic lifestyle, I see purple as a physical representation or lifelong motif that represents the power of resilience in the authentic life I live as an out, loud, and proud Black lesbian gender-non-conforming woman.

#black lesbian#the color purple#black queer#alice walker#black women#lesbian#lorraine hansberry#black qwoc#black resilience#gender nonconforming#gender noncomformity#writing#substack#self promo

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lorraine Hansberry’s likes and dislikes

April 1, 1960:

I LIKE:

Mahalia Jackson’s music

My husband — most of the time

dressed up

being admired for my looks

Dorothy Secules eyes

Dorothy Secules

Shakespeare

Having an appetite

Slacks

My homosexuality

Being alone

Eartha Kitt’s looks

Eartha Kitt

That first drink of Scotch

To feel like working

The little boy in “400 Blows”

The way I look

Certain flowers

The way Dorothy Talks

Older Women

Miranda D’Corona’s accent

Charming women

And/or intelligent women

I HATE

Being asked to speak

Speaking getting

Too much mail

My loneliness

My homosexuality

Stupidity

Most television programs

What has happened to Sidney Poitier

Racism

People who defend it

Seeing my picture

Reading my interviews

Jean Genet’s plays

Jean Paul Sartre’s writing

Not being able to work

Death

Pain Cramps

Being hung over

Silly women

As silly men

David Suskind’s pretensions

Sneaky love affairs.

I AM BORED TO DEATH WITH:

A RAISIN IN THE SUN!

alonzo Levister

drinking without happiness

Eartha Kitt

Being a Les

“Lesbians” the capital L variety

other peoples problems

The Race Problem

Silly white people

Rumors of War

the Great American money obsession

my own Loneliness

SEX

myself

Being a “Celebrity”

I want:

to work

to be in love!

Dorothy Secules (at the moment)

https://publish.illinois.edu/ihlc-blog/2018/06/04/lorraine-hansberry-letters-to-the-ladder

#queer theory#black lesbian#black queer#black women#lesbian#lorraine hansberry#literature#black literature#black authors#black playwright#black resilliance#black qwoc#young gifted and black

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

violent resistance to violent oppression wouldnt exist if there was no violent oppression in the first place. casualties of violent resistance to violent oppression are ultimately the sole blame of the violent oppressor

38K notes

·

View notes

Text

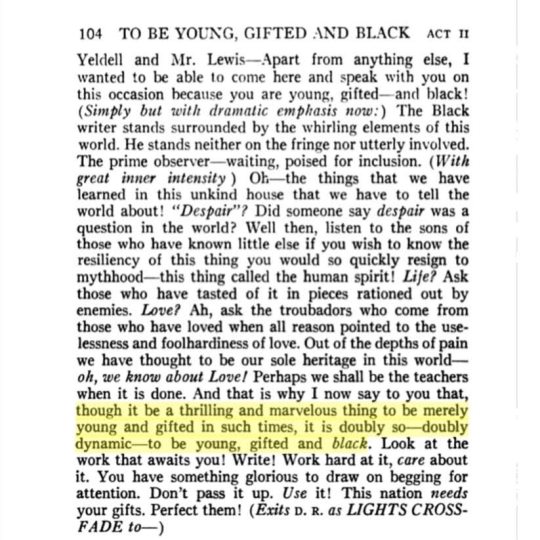

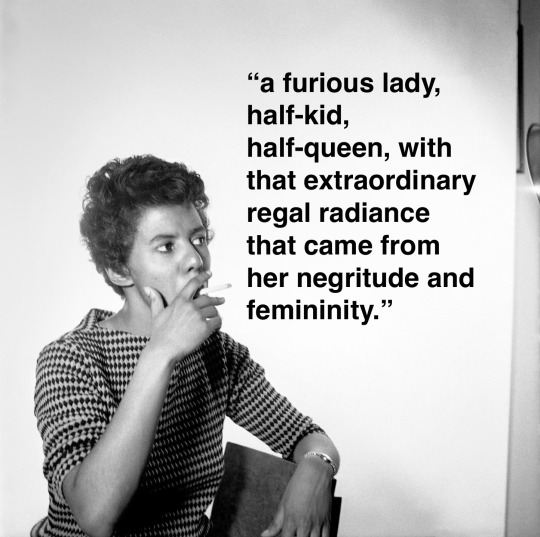

Lorraine Hansberry's lesbianism is one of my favorite pieces of Black literary history.

To be Young, Gifted, and Black

#lorraine hansberry#a raisin in the sun#lesbian#black lesbian#black women#black queer#young gifted and black

119 notes

·

View notes

Text

On Black Queer Resilience

sharing my playlist on black queer resilience here... being a black lesbian is my favorite part of my life.

#playlist#spotify#purple#the color purple#alice walker#whoopi goldberg#black lesbian#black resilliance#black women#black queer#black lgbt#black qwoc#Spotify

7 notes

·

View notes

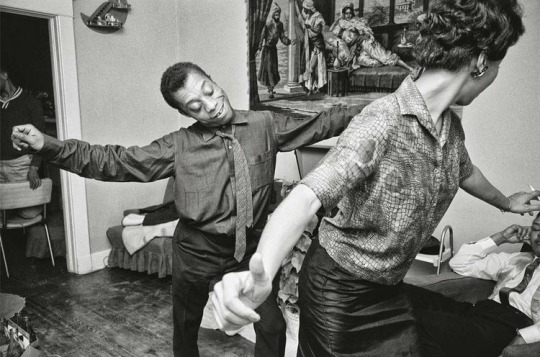

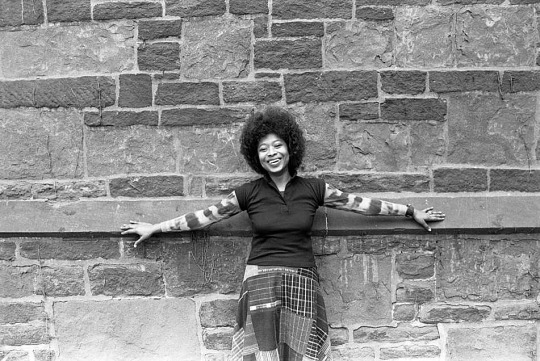

Photo

Author/Poet Alice Walker in New Haven, Connecticut (1977), photo by William R. Ferris

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

“All my life I had to fight. I had to fight my daddy. I had to fight my brothers. I had to fight my cousins and my uncles. A girl child ain’t safe in a family of men. But I never thought I’d have to fight in my own house. She let out her breath. I loves Harpo, she say. God knows I do. But I’ll kill him dead before I let him beat me.”

— Alice Walker, The Color Purple

181 notes

·

View notes

Text

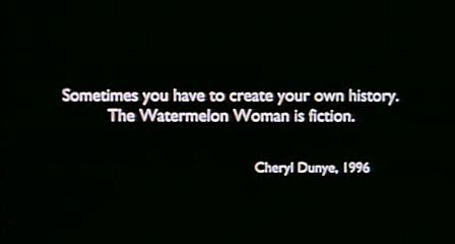

Webweaving -- Black Resilience -- To Be Young, Gifted and Black

The Watermelon Woman (1996) // Q.U.E.E.N Janelle Monae // To Be Young Gifted and Black Robert B. Nemiroff // Self Noname // Denise Huxtable // i Kendrick Lamar // A Different World Denise Huxtable // The Color Purple // Q.U.E.E.N Janelle Monae // The Color Purple // Stop Calling The Police On Me Dreamer Isioma // Toni Morrison // Lorraine Hansberry // boomboom Noname // Lorraine Hansberry

#webweaving#web weave#lorraine hansberry#denise huxtable#the color purple#alice walker#toni morrison#the watermelon woman#noname#janelle monae#dreamer isioma#kendrick lamar#against me!#black resilliance#black women#black beauty#generational trauma#generational healing

100 notes

·

View notes

Text

@sweatermuppet

1 note

·

View note