Text

the idea that restrooms, locker rooms, etc need to be single-sex spaces in order for women to be safe is patriarchy's way of signalling to men & boys that society doesn't expect them to behave themselves around women. it is directly antifeminist. it would be antifeminist even if trans people did not exist. a feminist society would demand that women should be safe in all spaces even when there are men there.

40K notes

·

View notes

Text

here’s a story about changelings

reposted from my old blog, which got deleted:

Mary was a beautiful baby, sweet and affectionate, but by the time she’s three she’s turned difficult and strange, with fey moods and a stubborn mouth that screams and bites but never says mama. But her mother’s well-used to hard work with little thanks, and when the village gossips wag their tongues she just shrugs, and pulls her difficult child away from their precious, perfect blossoms, before the bites draw blood. Mary’s mother doesn’t drown her in a bucket of saltwater, and she doesn’t take up the silver knife the wife of the village priest leaves out for her one Sunday brunch.

She gives her daughter yarn, instead, and instead of a rowan stake through her inhuman heart she gives her a child’s first loom, oak and ash. She lets her vicious, uncooperative fairy daughter entertain herself with games of her own devising, in as much peace and comfort as either of them can manage.

Mary grows up strangely, as a strange child would, learning everything in all the wrong order, and biting a great deal more than she should. But she also learns to weave, and takes to it with a grand passion. Soon enough she knows more than her mother–which isn’t all that much–and is striking out into unknown territory, turning out odd new knots and weaves, patterns as complex as spiderwebs and spellrings.

“Aren’t you clever,” her mother says, of her work, and leaves her to her wool and flax and whatnot. Mary’s not biting anymore, and she smiles more than she frowns, and that’s about as much, her mother figures, as anyone should hope for from their child.

Mary still cries sometimes, when the other girls reject her for her strange graces, her odd slow way of talking, her restless reaching fluttering hands that have learned to spin but never to settle. The other girls call her freak, witchblood, hobgoblin.

“I don’t remember girls being quite so stupid when I was that age,” her mother says, brushing Mary’s hair smooth and steady like they’ve both learned to enjoy, smooth as a skein of silk. “Time was, you knew not to insult anyone you might need to flatter later. ‘Specially when you don’t know if they’re going to grow wings or horns or whatnot. Serve ‘em all right if you ever figure out curses.”

“I want to go back,” Mary says. “I want to go home, to where I came from, where there’s people like me. If I’m a fairy’s child I should be in fairyland, and no one would call me a freak.”

“Aye, well, I’d miss you though,” her mother says. “And I expect there’s stupid folk everywhere, even in fairyland. Cruel folk, too. You just have to make the best of things where you are, being my child instead.”

Mary learns to read well enough, in between the weaving, especially when her mother tracks down the traveling booktraders and comes home with slim, precious manuals on dyes and stains and mordants, on pigments and patterns, diagrams too arcane for her own eyes but which make her daughter’s eyes shine.

“We need an herb garden,” her daughter says, hands busy, flipping from page to page, pulling on her hair, twisting in her skirt, itching for a project. “Yarrow, and madder, and woad and weld…”

“Well, start digging,” her mother says. “Won’t do you a harm to get out of the house now’n then.”

Mary doesn’t like dirt but she’s learned determination well enough from her mother. She digs and digs, and plants what she’s given, and the first year doesn’t turn out so well but the second’s better, and by the third a cauldron’s always simmering something over the fire, and Mary’s taking in orders from girls five years older or more, turning out vivid bolts and spools and skeins of red and gold and blue, restless fingers dancing like they’ve summoned down the rainbow. Her mother figures she probably has.

“Just as well you never got the hang of curses,” she says, admiring her bright new skirts. “I like this sort of trick a lot better.”

Mary smiles, rocking back and forth on her heels, fingers already fluttering to find the next project.

She finally grows up tall and fair, if a bit stooped and squinty, and time and age seem to calm her unhappy mouth about as well as it does for human children. Word gets around she never lies or breaks a bargain, and if the first seems odd for a fairy’s child then the second one seems fit enough. The undyed stacks of taken orders grow taller, the dyed lots of filled orders grow brighter, the loom in the corner for Mary’s own creations grows stranger and more complex. Mary’s hands callus just like her mother’s, become as strong and tough and smooth as the oak and ash of her needles and frames, though they never fall still.

“Do you ever wonder what your real daughter would be like?” the priest’s wife asks, once.

Mary’s mother snorts. “She wouldn’t be worth a damn at weaving,” she says. “Lord knows I never was. No, I’ll keep what I’ve been given and thank the givers kindly. It was a fair enough trade for me. Good day, ma’am.”

Mary brings her mother sweet chamomile tea, that night, and a warm shawl in all the colors of a garden, and a hairbrush. In the morning, the priest’s son comes round, with payment for his mother’s pretty new dress and a shy smile just for Mary. He thinks her hair is nice, and her hands are even nicer, vibrant in their strength and skill and endless motion.

They all live happily ever after.

*

Here’s another story:

Gregor grew fast, even for a boy, grew tall and big and healthy and began shoving his older siblings around early. He was blunt and strange and flew into rages over odd things, over the taste of his porridge or the scratch of his shirt, over the sound of rain hammering on the roof, over being touched when he didn’t expect it and sometimes even when he did. He never wore shoes if he could help it and he could tell you the number of nails in the floorboards without looking, and his favorite thing was to sit in the pantry and run his hands through the bags of dry barley and corn and oat. Considering as how he had fists like a young ox by the time he was five, his family left him to it.

“He’s a changeling,” his father said to his wife, expecting an argument, but men are often the last to know anything about their children, and his wife only shrugged and nodded, like the matter was already settled, and that was that.

They didn’t bind Gregor in iron and leave him in the woods for his own kind to take back. They didn’t dig him a grave and load him into it early. They worked out what made Gregor angry, in much the same way they figured out the personal constellations of emotion for each of their other sons, and when spring came, Gregor’s father taught him about sprouts, and when autumn came, Gregor’s father taught him about sheaves. Meanwhile his mother didn’t mind his quiet company around the house, the way he always knew where she’d left the kettle, or the mending, because she was forgetful and he never missed a detail.

“Pity you’re not a girl, you’d never drop a stitch of knitting,” she tells Gregor, in the winter, watching him shell peas. His brothers wrestle and yell before the hearth fire, but her fairy child just works quietly, turning peas by their threes and fours into the bowl.

“You know exactly how many you’ve got there, don’t you?” she says.

“Six hundred and thirteen,” he says, in his quiet, precise way.

His mother says “Very good,” and never says Pity you’re not human. He smiles just like one, if not for quite the same reasons.

The next autumn he’s seven, a lucky number that pleases him immensely, and his father takes him along to the mill with the grain.

“What you got there?” The miller asks them.

“Sixty measures of Prince barley, thirty two measures of Hare’s Ear corn, and eighteen of Abernathy Blue Slate oats,” Gregor says. “Total weight is three hundred fifty pounds, or near enough. Our horse is named Madam. The wagon doesn’t have a name. I’m Gregor.”

“My son,” his father says. “The changeling one.”

“Bit sharper’n your others, ain’t he?” the miller says, and his father laughs.

Gregor feels proud and excited and shy, and it dries up all his words, sticks them in his throat. The mill is overwhelming, but the miller is kind, and tells him the name of each and every part when he points at it, and the names of all the grain in all the bags waiting for him to get to them.

“Didn’t know the fair folk were much for machinery,” the miller says.

Gregor shrugs. “I like seeds,” he says, each word shelled out with careful concentration. “And names. And numbers.”

“Aye, well. Suppose that’d do it. Want t’help me load up the grist?”

They leave the grain with the miller, who tells Gregor’s father to bring him back ‘round when he comes to pick up the cornflour and cracked barley and rolled oats. Gregor falls asleep in the nameless wagon on the way back, and when he wakes up he goes right back to the pantry, where the rest of the seeds are left, and he runs his hands through the shifting, soothing textures and thinks about turning wheels, about windspeed and counterweights.

When he’s twelve–another lucky number–he goes to live in the mill with the miller, and he never leaves, and he lives happily ever after.

*

Here’s another:

James is a small boy who likes animals much more than people, which doesn’t bother his parents overmuch, as someone needs to watch the sheep and make the sheepdogs mind. James learns the whistles and calls along with the lambs and puppies, and by the time he’s six he’s out all day, tending to the flock. His dad gives him a knife and his mom gives him a knapsack, and the sheepdogs give him doggy kisses and the sheep don’t give him too much trouble, considering.

“It’s not right for a boy to have so few complaints,” his mother says, once, when he’s about eight.

“Probably ain’t right for his parents to have so few complaints about their boy, neither,” his dad says.

That’s about the end of it. James’ parents aren’t very talkative, either. They live the routines of a farm, up at dawn and down by dusk, clucking softly to the chickens and calling harshly to the goats, and James grows up slow but happy.

When James is eleven, he’s sent to school, because he’s going to be a man and a man should know his numbers. He gets in fights for the first time in his life, unused to peers with two legs and loud mouths and quick fists. He doesn’t like the feel of slate and chalk against his fingers, or the harsh bite of a wooden bench against his legs. He doesn’t like the rules: rules for math, rules for meals, rules for sitting down and speaking when you’re spoken to and wearing shoes all day and sitting under a low ceiling in a crowded room with no sheep or sheepdogs. Not even a puppy.

But his teacher is a good woman, patient and experienced, and James isn’t the first miserable, rocking, kicking, crying lost lamb ever handed into her care. She herds the other boys away from him, when she can, and lets him sit in the corner by the door, and have a soft rag to hold his slate and chalk with, so they don’t gnaw so dryly at his fingers. James learns his numbers well enough, eventually, but he also learns with the abruptness of any lamb taking their first few steps–tottering straight into a gallop–to read.

Familiar with the sort of things a strange boy needs to know, his teacher gives him myths and legends and fairytales, and steps back. James reads about Arthur and Morgana, about Hercules and Odysseus, about djinni and banshee and brownies and bargains and quests and how sometimes, something that looks human is left to try and stumble along in the humans’ world, step by uncertain step, as best they can.

James never comes to enjoy writing. He learns to talk, instead, full tilt, a leaping joyous gambol, and after a time no one wants to hit him anymore. The other boys sit next to him, instead, with their mouths closed, and their hands quiet on their knees.

“Let’s hear from James,” the men at the alehouse say, years later, when he’s become a man who still spends more time with sheep than anyone else, but who always comes back into town with something grand waiting for his friends on his tongue. “What’ve you got for us tonight, eh?”

James finishes his pint, and stands up, and says, “Here’s a story about changelings.”

32K notes

·

View notes

Text

Free Persuasion Typeset

So this is a typeset I did for Persuasion by Jane Austen, using the transcript from Project Gutenburg (definitely check them out if you're looking for free/public domain books!).

This typeset is for half letter and is free to use for bookbinding purposes (personal use only), I just ask that you please leave credit and consider liking/reblogging if possible!

The file can be found here:

https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/1S2wl_PuxCupofnDpqGuk7VjMHYFMWC6g?usp=sharing

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

we used to get prescribed a summer on the seaside. now we just get told to go touch grass. the economy is in shambles

11K notes

·

View notes

Text

having online friends is sooooo crazy because it starts by sending ridiculous memes and then one day it’s like omg. home is a person I’ve never physically met

26K notes

·

View notes

Text

"In Pieces but Still Holding It Together." By Bouke de Vries (2020).

See more of his stuff here.

20K notes

·

View notes

Text

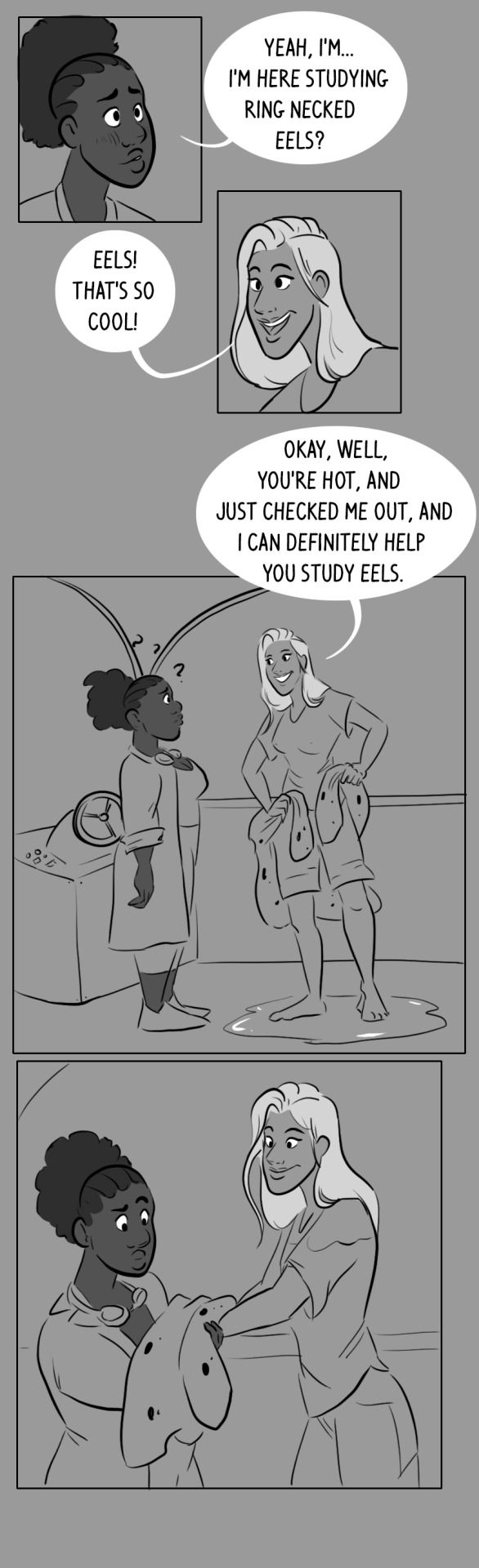

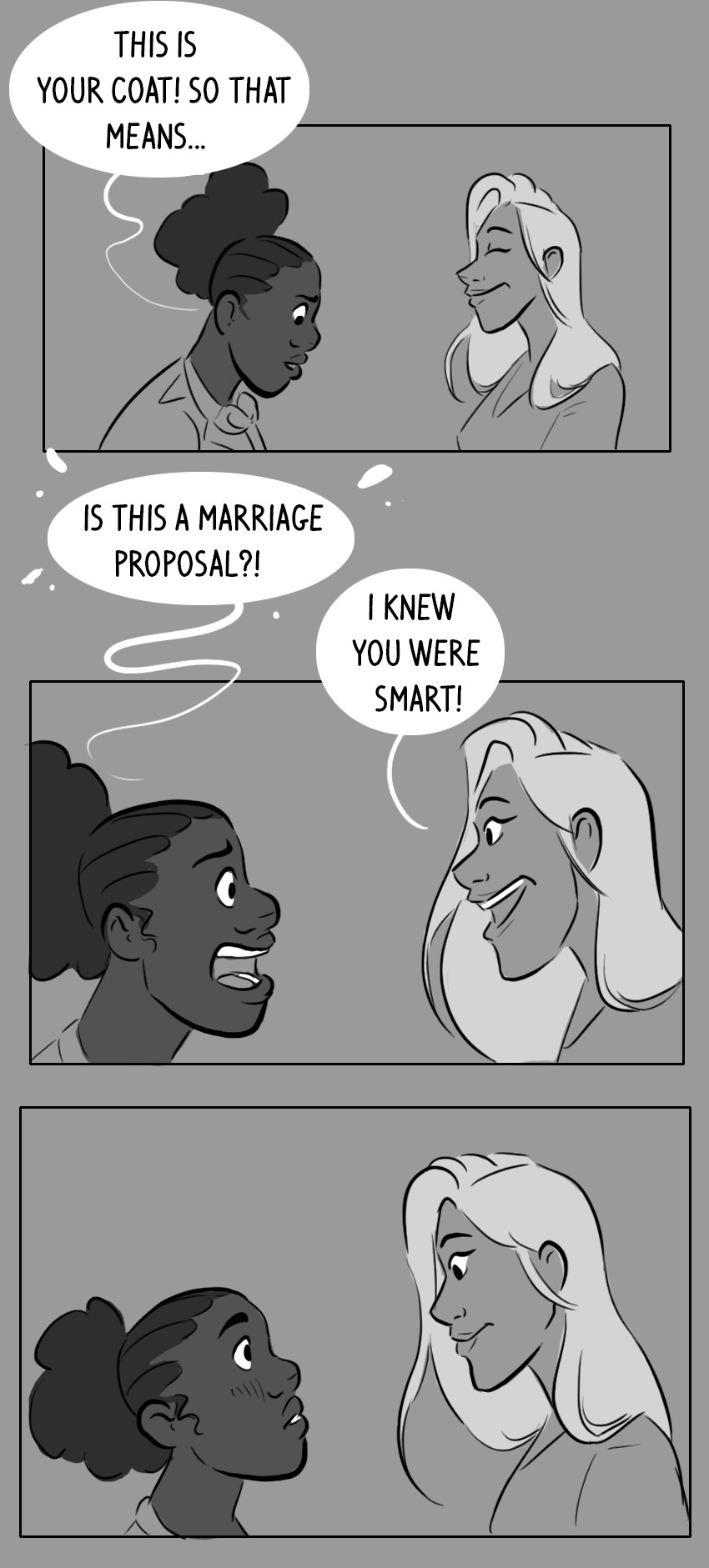

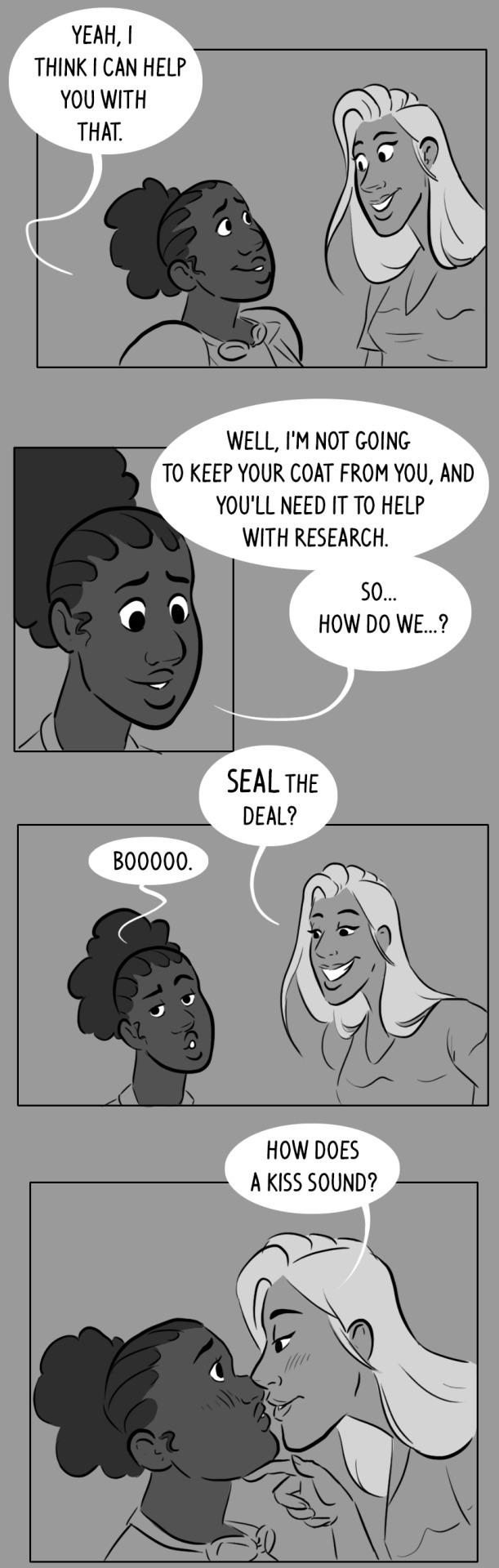

Seal the Deal

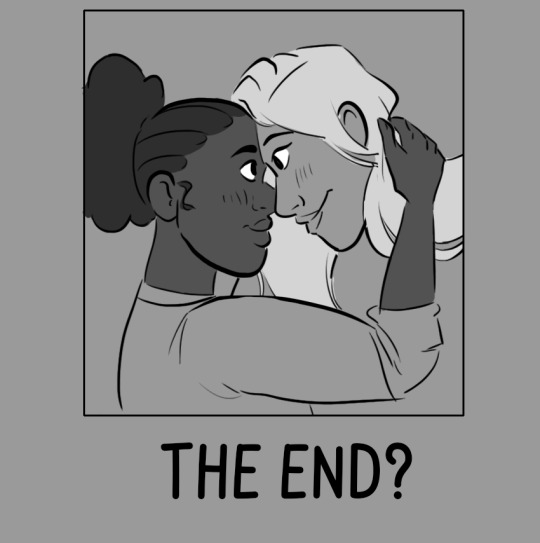

Here's my latest comic, Seal the Deal! Based on this post.

If Kleo and Aisling sparked joy I could be convinced to make more parts if they get enough love, I have a lot of little adventures as they navigate being suddenly married bopping around in my head.

Tips welcome on my Kofi!

Here's more comics!

11K notes

·

View notes

Note

Libraries in many places are funded based on the number of active patrons we have.

100% yes, borrow those ebooks and audiobooks.

But if you're able to access in-person library services, go use them too. Put in a hold so they have to ship you a book from another branch, use the printer and photocopier, go sit and read a book in one of their comfy chairs, get out of your house and have a change of pace by doing homework at the library.

When I was a teen I read way too many books. And I always (accidentally) requested too many library holds then wound up not being able to finish them all before their due dates. I felt bad about this before an encounter I had one day when checking out my usual three tote bags of books. A librarian I didn't know recognized my name (cause they'd been processing all my incoming holds), and thanked me.

Apparently I'd been borrowing so many books I'd increased the branch's budget. It didn't matter that I never read all those books. What mattered was that I requested them, took care of them and returned them in good condition, thereby increasing the circulation stats enough that they had numerical proof to argue that that little rural library branch deserved a budget increase.

I had the same thing happen in university, living in an area where there wasn't a library branch close. The library tried to patch this with a bookmobile stop and a set of lockers at the community centre where you could request holds. They also had a vending machine of new popular releases and a return slot. The bookmobile stop was at a bad time for me and so I used the lockers. And felt bad at making library employees haul all of the books I wanted to read, sometimes taking up multiple lockers with all my holds.

Then one day the lockers were temporarily out of order for repairs and I had to get all my holds rerouted to the bookmobile for a bit. When I stopped by to pick up my holds (dragging my boyfriend with me cause there were too many books for me alone to carry), I learned that I was famous among library staff. I was apparently the book lockers number one patron and was again responsible for a budget increase.

Sometimes libraries just do things to see if they can reach their patrons. And the participation numbers matter when they're going through the budget at the end of the fiscal year and seeing if they have enough interest to run it again. The book lockers was originally a trial project and it's still in operation almost a decade later.

Hey I know you're not a librarian, but you likely know more than I do and all my sources seem way too confusing to me. Does checking out digital books help support and fund public libraries?

I would assume so, I don't really have any sources for it but as far as I'm aware using any service that the library provides shows that there is a demand in the community for it, which would be a net positive for acquiring funding. At the end of the day they put those resources out there for a reason, so don't be shy about using them :D

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

"why do I feel so terrible?"

-person who forgot to take their not-feeling-terrible medication

32K notes

·

View notes

Text

Masterpost

Aragorn has sent his Captain north with two missions: to make a strategic survey of the ruins along Lake Evendim, and to relax and enjoy himself at Pippin’s wedding.

Boromir has more trouble obeying one than the other.

Chapter 1: Dahlia

Chapter 2: Bluebell

Chapter 3: Rose & Jasmine

Chapter 4: Strawberry

Chapter 5: Rockrose

Epilogue: Forget-Me-Not

Boromir/Original Female Character, Merry Brandybuck, Pippin Took, Samwise Gamgee, Diamond Took, Estella Bolger, Fatty Bolger, Elanor Gamgee, Aragorn, Faramir, Eowyn, Arwen, Elboron, character death fix, Boromir Lives, a Shire wedding, culture clashes

Rating: T+

Warnings: Adult humor/themes/language, alcohol and tobacco usage, mentions of PTSD and past traumatic events.

***DISCLAIMER: All depictions of OC Fern Whitfoot are of an adult hobbit. Any interactions suggesting otherwise will be blocked and/or reported if necessary.***

Status: Complete

Word Count: 35k

Notes:

Artwork: All artwork throughout this fic is mine, unless credit is otherwise given.

Fan art: On that note, if you draw art for this fic, I’ll reblog it and slot it into the story with credit, if you consent! Just tag me @eternal-vambraces, or message it to me directly.

Flora: The flower meanings in this story are pulled from Floriography by Jessica Roux, except where I took creative liberties or made things up (such as the meanings of bells of Ireland Tookbank, milkweed, and rockrose). Incidentally, this is a gorgeous book, perfect for any fans of the Victorian flower language.

Character depictions: There’s no rhyme or reason as to why some characters look more or less like their movie counterparts. I like to play with character designs, and these are the ones that settled in place for this fic. It’s nothing personal against any of the actors or their portrayals.

479 notes

·

View notes