Text

Born in Brisbane.

Bachelor of Arts (Fine Art and Visual Culture) - Curtin University

2018-2019 in Phnom Penh.

Now back in Brisbane.

0 notes

Photo

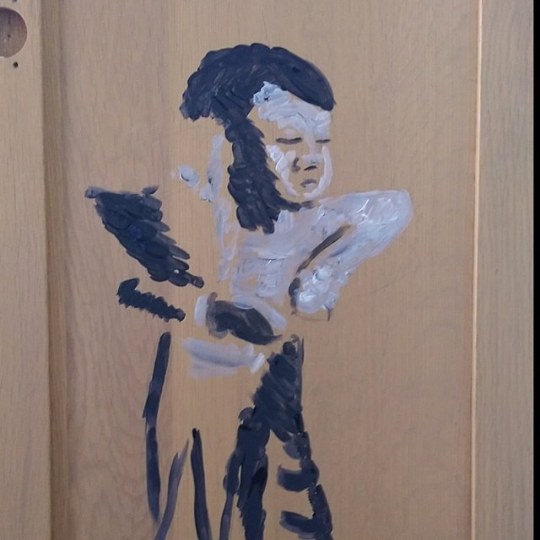

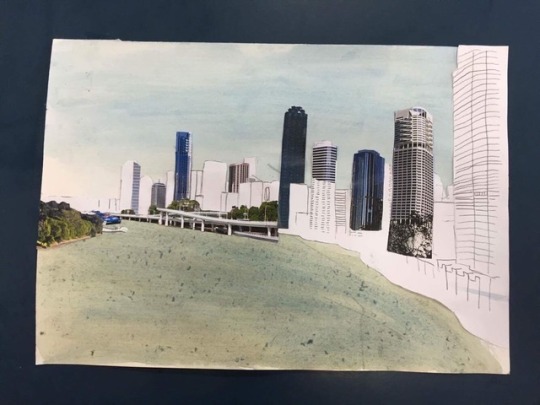

KTV, 2018, ink on paper.

1 note

·

View note

Text

World War I and Australian Art: Fighting for art in Australia

World War I had a significant impact on Australian society, being the first international war Australia would engage in on its’ own accord. The way in which this affected society’s function and Australia’s relationship with the world was profound. The art world, so inherently intertwined, held a mirror up to society during this time, reflecting this change. Socially, culturally, and economically, Australia had changed and many of these artists at the time were embracing this change, as well as the new influence of Modernism coming from across the world. However, some artists and art critics were hesitant to accept this change due to the nature of the works and the artists creating them. Within this essay, social, cultural, political, and economic influences within the interwar period will be examined to understand how Australian Modernism was shaped during this time.

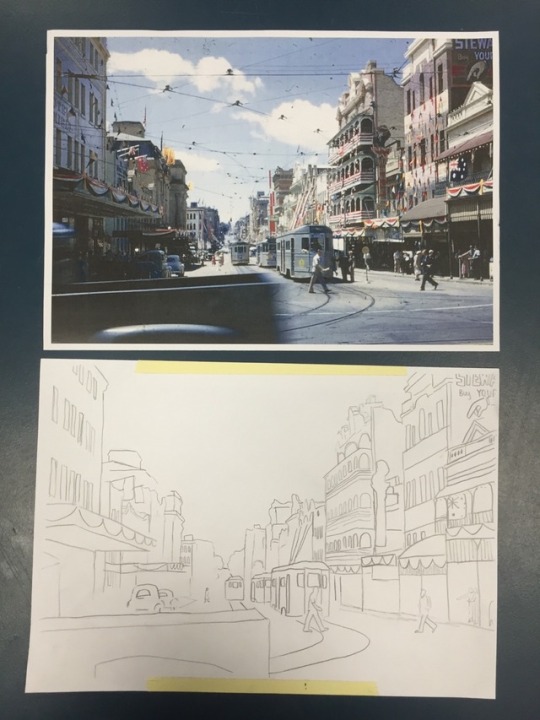

Post World War I, women had been brought into the forefront of society, entering the workforce and other roles in greater numbers than ever before. With many male artists fighting overseas, women also documented the war from home, painting the strange world that was Australia during WWI. During the period of early modernism in Australian art, women were largely pioneering the movement (Hoorn 1992). The movement was dismissed as frivolous and lacking in talent due to this fact and many male artists neglected to engage in modernist techniques until the mid 1930s. In the words of art historian, Bernard Smith, ‘women played a greater part in forming contemporary taste in Australia than they have before or since’ (Williams 1995). Grace Cossington’s works examine women’s existence within the domestic sphere from a female perspective (Hoorn 1992) Women were central to Australian Modernism and the lack of appreciation of women as artists and proponents of a central art movement somewhat allowed female Modernists to develop in a way male artists could not (Hoorn 1992). Grace Cossington honed her skills in Post-Impressionism during the early 1900s, painting images of Australian life at the time. She gave scenes life, movement, stillness, and emotion, but neglected depth and instead opted for a flat plane existence for the image. The prince (1920) (Figure 1) shows what would be imagined as an extravagant scene, instead opting for the focus to be on the fact is a perspective, a little person in the crowd looking on, out of focus. Cossington did this in stark contrast to the way Australians had painted these scenes prior to Modernism. Cossington’s paintings, along with many other women’s, identified themselves as Modernist while straying from the masculine narrative Modernism is so often imagined as (Hoorn 1992).

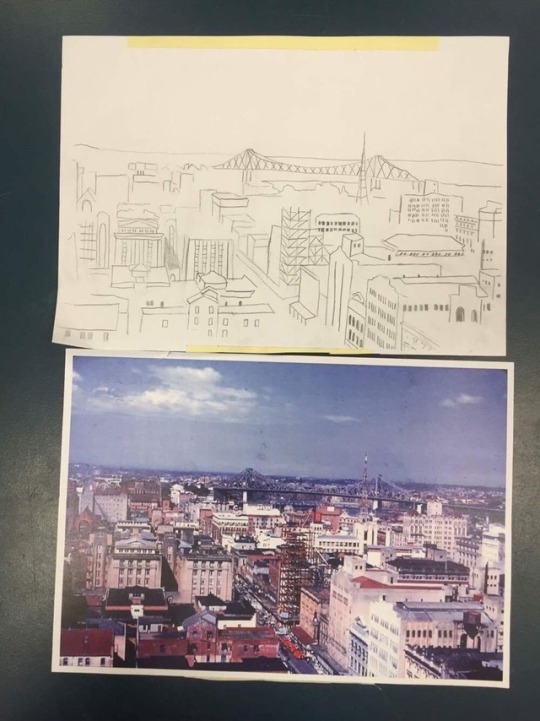

Following WWI, Australia and the world’s economy was thriving. Companies had many new inventions and plenty of public interest to back them. Australians were thrilled about the modernisation of domestic life. The new technology and opportunity changed lives and created a sense of excitement. Artists depicted this in their works, this new economic climate, along with development that came with it (Coppel 1995). Many artists had moved to Sydney from Melbourne, the former hub of artistic expression within Australia, and others moved overseas to experience the works of other Modernist painters in Europe (Speck 2014). The development in Sydney became a focus for a lot of artists and The Sydney Harbour Bridge was one of these developments. Dorrit Black’s painting The Bridge (1930) (Figure 2) drew controversy over its unconventional nature. Her somewhat Cubist approach to perspective was unlike any depiction of Australian landscape or cityscape before it. Having moved to London in the 1920s, she had witnessed new ways of depicting landscape and colour (Speck 2014). Another symbol of the new technology emerging was the linocut. Claude Flight, a pioneer of the linocut print, believed modern art should ‘reflect the energy of the modern age’ (Leaper 2016). Those influenced by him included Margaret Preston who famously produced works of Australian flora in linocut print (Figure 3). She was a proponent of the Modernist idea of art for the ‘everyman’, promoting the accessibility of art. Her linocuts were easily printed and reproduced, making them able to be put in homes and used on textiles. She wrote in Art in Australia, ‘The easiest way to understand modern art is to buy an example and live with it. Custom makes consciousness’ (Preston 1929, quoted by AGNSW). The techniques used and the images depicted showed an economic shift in Australian society, changing the way art progressed in the early 1920s.

Modern art had begun flowing into Australia by the 1920s but the climate it entered was not so welcoming. After the horrors of World War I, anything considered too heavily European-influenced was regularly looked upon in a negative light. Modernism proved to be polarising in its nature and had garnered many critics, along with its fans. The warfare between Modernism and Conservative values went on relentlessly. A renewed sense of nationalism could be felt post World War I and this idea of the ‘stoic, hard-working Australian’ was seen to be under threat from Modernism (Underhill 1991). Those that opposed the movement regularly cited the ‘deviant’ nature the works and artists as their reasoning for opposition (Snell 1987). Norman Lindsay was a key proponent of Modernism in Australia and sought to have his works exhibited by the South Australian Society of Artists in 1924 (Snell 1987). However, three of his eleven submissions were rejected for obscenity and he subsequently withdrew his submission entirely, then hiring the gallery next door (Lindsay & Wingrove 1990). Lindsay’s exhibition was highly successful and was a direct rejection of the reactionary Conservative movement at the time. In particular, his works including powerful images of female nudity drew controversy (Figure 3). Sydney Ure Smith, an art publisher and promoter at the time, was quoted to have said ‘it’s not so much what he does, it’s the awful ideas he puts into your head’ (Underhill 1991). From that point onwards, the war between Conservatives and Modernism continued, becoming a political pawn. Robert Menzies supported the opening of the Australian Academy of Art in 1937, run by the conservatives of the art world, while, H.V. Evatt, on the other side, supporting the Contemporary Art Society (Snell 1987). This scandalisation of Modernist art had created a split in the art world and, beyond this, fuel for cultural and political fire in Australia. The works, however, would become integral in the history of Australian art, regardless of the reviews it received from critics at the time.

The Modernist movement within Australia continues to be important in Australian history today. The artists and their works tell a story of a young society and its development in the early 20th century. A number of factors impacted the growth and prevalence of Modernist art in Australia at the time. These included the bringing of women to the forefront as artists, consumers and workers, the new technology being rapidly developed at the time, and the scandalisation of art and modernism, garnering the interest of the public. Modernism thrived in a difficult environment during both wars, but within Australia, the inter-war period created a climate in which it would become a focus of both artists and the public, fixing itself firmly within the history of Australian Art.

REFERENCES

Coppel, Stephen. 1995. Linocuts Of The Machine Age. [Aldershot]: Scolar Press.

Hoorn, Jeanette. 1992. "Misogyny And Modernist Painting In Australia: How Male Critics Made Modernism Their Own". Journal Of Australian Studies 16 (32): 7-18. doi:10.1080/14443059209387082.

Leaper, Hana. 2016. "‘Old-Fashioned Modern’: Claude Flight's Lino-Cuts And Public Taste In The Interwar Period". Modernist Cultures 11 (3): 389-408. doi:10.3366/mod.2016.0147.

Lindsay, Norman, and Keith Wingrove. 1990. Norman Lindsay On Art, Life, And Literature. Lucia, Qld., Australia: University of Queensland Press.

Preston, Margaret, Art in Australia, 1929, quoted in Art Gallery New South Wales, “Margaret Preston, art and life,” http://www.artgallery.nsw.gov.au/sub/preston/artist_1920.html

Snell, T and Curtin University of Technology for the Dept. of Visual Arts (1987). Scandalized : public perceptions of the arrival and emergence of modernism in Australian art. [video] Available at: https://echo360.org.au/media/1b8add4f-f17e-4788-ab71-e2b63454fcc1/public [Accessed 8 Mar. 2019].

Speck, Catherine. 2014. "Dorrit Black: Unseen Forces, Art Gallery Of South Australia, 14 June – 7 September 2014". Australian And New Zealand Journal Of Art 14 (2): 214-216. doi:10.1080/14434318.2014.973009.

Underhill, Nancy D. H. 1991. Making Australian Art 1916-49. Melbourne: Oxford University Press.

Williams, John F. 1995. The Quarantined Culture: Australian Reactions To Modernism, 1913-1939. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Many Faces of Picasso: Social and cultural influence on an artist

Pablo Picasso is well known for his artistic style and the ways it evolved over his career. This evolution is not something that occured purely from within, instead, it was influenced heavily by the the events in the world around him. Picasso began with his Impressionist works, presenting themselves in Blue and Rose periods, but was then influenced by the African art being imported into Europe at the time. This manifested in simplified, angular figures and ultimately led to his endeavour to entirely reinvent art as it was known to him. From this Cubism was born, soon becoming a significant part of his career, influenced by both his own want for change and the changes occuring in how art was made worldwide. His new style was used to depict the anguish of war, having been a constant in the lives of those in the early 20th century. In this essay, each of these key socio-cultural elements will be discussed in relation to the influence on Picasso’s works and key pieces examined for their representation of transformation in each of the periods of his life. Through this discussion the strong influence of society throughout Picasso’s life on his work will be understood.

Picasso began painting during the Impressionist period and his works reflected this movement heavily, focussing on colour and mood more than the image itself. His personal style at this time focussed first on strong blue tones. He was influenced by a deep depression which began in 1901, then coinciding with his friend Casagemas’ suicide (Warncke and Ingo 1997). As he began to paint depressing portraits of his deceased friend (see Figure 2), the public became disinterested with his works, not wanting to use the works decoratively in their homes. During this period he made little money, was living in poverty like many in Europe at that time (Kaplan 1993) and seeing few of his friends (Solomon 1995). He continued to paint moody works, now depicting loneliness and poverty (see Figure 1). This aesthetic choice still aligned itself with the Impressionists, allowing mood to be strongly conveyed through colour and brush strokes. Throughout his career, he held onto these values of colour, shape and brush stroke to create a mood. His focus on shape and angles that began during this period followed him into his African period and further into Cubism.

Picasso began his transition into proto-Cubism in 1906, lasting until 1908. This was spurred by the French imperialist expansion into Sub-Saharan Africa and the works from the people in Sub-Saharan Africa being brought back to France (Gikandi 2003). It was in this climate of African interest that Henri Matisse showed him a mask that had been taken from the Dan people. From these works, Picasso began to form a new idea of the way in which art could or should be created. “Men had made those masks and other objects for a sacred purpose, a magic purpose, as a kind of mediation between themselves and the unknown hostile forces that surrounded them, in order to overcome fear and horror by giving it form and an image. At that moment I realised that this was what painting was all about. Painting isn't an aesthetic operation; it's a form of magic designed as mediation between this strange, hostile world and us, a way of seizing power by giving form to our terrors as well as our desires. When I came to that realisation, I knew I had found my way ” (Warncke and Ingo 1997). This ‘realisation’ was evident in his works from the time, such as Head of a Sleeping Woman (Study for Nude with Drapery) (1907) (Figure 3). In this work, the head has more angular, simplified features than seen before in Picasso’s work. The heavy eye rounding and indentation can be seen as a strong influence, as well as, elongated face shapes (Nuttall 2006). This influence was carried on into the Cubist period, for which he is so well known.

Following the African period, Picasso had found his new understanding of art and its creation and began to manifest an idea to relearn what art was to him. He spent years with this focus of retraining his brain, abandoning the Naturalist way of painting, creating new fragmented images in a drastic move away from classical painting (Apollinaire and Eimert 2012). On the creation of Cubism, he said, ‘I saw that everything had been done. One had to break, to make one’s revolution and to start at zero’ (Apollinaire and Eimert 2012). Cubism thus rejected all tradition that had come before it. Picasso was undoubtedly influenced by the revolution in the art world, as well as the African art influence at the time. This social and artistic revolution was happening all around him, Braque working on the idea of Cubism with him, Dadaists creating anti-art (Dickie 1984), Surrealists depicting taboo (Frey 1936), Cubism became a step in the abandonment of tradition in line with the movements without them. The understanding of different reasons to create art coming from the colonization of Africa and the cultural influence that had on the European world lead to Western artists creating new works based upon values from other cultures (Brooks 1956). Picasso’s newfound, more worldly, understanding pushed the creation of new works based on world issues later on in his career.

During the course of Picasso’s life, war was a constant. From World War I, to the Spanish Civil War, to World War II, the ongoing turmoil in the world around him likely influenced him to create darker, more chaotic pieces. One of these is Guernica (1937), (see Figure 6) commissioned by Spanish Nationalists, based on the bombing of the Basque town by Nazi Germany (Clark 2013). However, after exhibiting Guernica in 1937, Picasso said he had not explicitly painted about war, ‘because I am not the kind of painter who goes out like a photographer for something to depict. I have no doubt that the war is in these paintings I have done. Later on perhaps the historians will find them and show that my style has changed under the war's influence’ (Kimmelman 1999). His opinion of himself as an artist had changed by the end of WWII, saying ‘What do you think an artist is? An imbecile who has only eyes, if he is a painter… Far, far from it: at the same time, he is also a political being, constantly aware of the heartbreaking, passionate, or delightful things that happen in the world, shaping himself completely in their image... No, painting is not done to decorate apartments. It is an instrument of war for attack and defense against the enemy’ (Téry 1945). It seems evident that he had developed new views about war and the importance of art as a tool for expression. Europe had suffered greatly during the war and Picasso was not immune to the reality of war and suffering. In his works during WWII, the chaotic violence and despair seemed to seep out of his works, abandoning the vibrant colours and emphasising abstraction more heavily than ever.

Throughout history, artists have always taken inspiration from the world around them and their situation. Colonialism, war, mental health issues, and the artistic community all played key roles in the evolution of the work Picasso produced. During his lifetime the world around him impacted both what he depicted and the way in which it was depicted. Through this essay, the transformation throughout his career can be understood through the changes in the world around Picasso and the way in which he saw this world. From an examination of the socio-cultural influences in Europe in the early 20th century, each period of his artistic endeavours can be understood. The Blue Period was caused by his depression and a friend’s suicide, the African period was by the imperialism into Africa by the French, Cubism was spurred by the general distaste for traditional techniques and, ultimately, influenced heavily by his African period, and finally, the ongoing wars in the 20th century influenced the final period of his works. Picasso’s career illustrates the influence of socio-cultural events on an artist’s life and by understanding this, other artists trajectories can be further understood.

REFERENCES

Apollinaire, Guillaume, and Eimert, Dorothea. 2012. Cubism. New York: Parkstone International. Accessed July 5, 2018. ProQuest Ebook Central.

Brooks, Dorothy. 1956. "The Influence Of African Art On Contemporary European Art". African Affairs 55 (218): 51-59. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.afraf.a094367.

Clark, Timothy J. 2013. Picasso And Truth: From Cubism To Guernica. Princeton (N.J.): Princeton University Press.

Dickie, George. 1997. The Art Circle: A Theory Of Art. Evanston, Ill.: Chicago Spectrum Press.

Frey, John G. 1936. "From Dada To Surrealism". Parnassus 8 (7): 12. doi:10.2307/771260.

Gikandi, Simon. 2003. "Picasso, Africa, and the Schemata of Difference." Modernism/Modernity 10 (3): 455-480.

Kaplan, Temma. 1993. Red City, Blue Period. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Kimmelman, Michael. 1999. "ART REVIEW; Occupied Paris And The Politics Of Picasso". New York Times, , 1999. https://www.nytimes.com/1999/02/05/arts/art-review-occupied-paris-and-the-politics-of-picasso.html.

Leighten, Patricia. 1990. "The White Peril and L'Art nègre: Picasso, Primitivism, and Anticolonialism." The Art Bulletin 72 (4): 609-630.

Nuttall, Sarah. 2006. African And Diaspora Aesthetics. Durham: Duke University Press.

Solomon, Barbara. 1995. "Callow Young Genius". New York Times, , 1995.

Téry, Simone. 1945. "Picasso N'est Pas Officier Dans L'armée Française". Les Lettres Françaises, , 1945.

Warncke, Carsten-Peter, and Walther Ingo. 1997. Pablo Picasso: 1881-1973. Taschen.

0 notes