Text

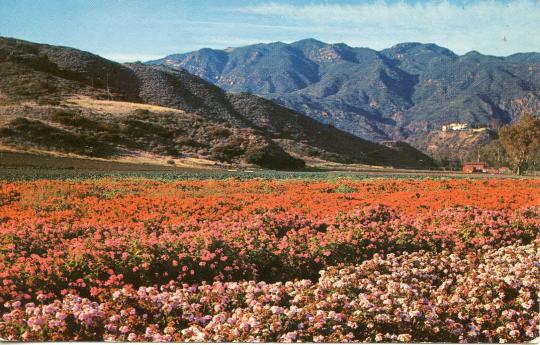

Unknown, Japanese geranium farm near Malibu Beach, 1950s

This postcard shows the colorful geranium farm that used to be visible from the Pacific Coast Highway in central Malibu, just west of Malibu Creek. This was the Takahashi Geranium Farm owned and operated by a Japanese-American family from at least the 1940s to the early 1970s. Serra Retreat is visible in the distance at the right of the image.

Eric Wienberg Collection of Malibu Matchbooks, Postcards, and Ephemera 0129:

191 notes

·

View notes

Text

0 notes

Text

Panorama of San Francisco, USA. 1878. High Resolution.

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

0 notes

Text

Once a month, John Cobb stops by Evergreen Cemetery in East Oakland to check on the Jonestown Memorial. Eleven of his family members are buried there, including his mother and five siblings. He’ll sit on the bench, contemplating those he lost, or get to work wiping away the acorn shells and foxtails on the granite memorial plaques he helped put in place over a decade ago.

The memorial exists to ensure the stories of his loved ones aren’t forgotten. It sits on a half-moon-shaped hill in the cemetery, which is located just below MacArthur Boulevard between 64th and 68th avenues, overlooking the Coliseum in the distance. The memorial is remarkably humble — four plaques with 918 engraved names of the Peoples Temple members who died 45 years ago — and belies how big Jonestown has loomed in the collective imagination.

Cobb lives near the memorial and now runs a furniture business. But when the Jonestown tragedy happened, he was 18 years old and part of Jim Jones’ personal security detail in Guyana. Jones started Peoples Temple church in the 1950s, first in Indiana then San Francisco, championing racial equality during a time of overt segregation. It ended with him using drugs, paranoid in a “promised land” he called Jonestown in the interior jungle of Guyana, where he forced death on members via poisoned Flavor Aid and gunshot. Over a third were under the age of 18.

When Cobb is at the memorial, reading the names, his memories are nothing like the horrific images from Guyana that flooded the media in the days that followed. What he sees are ordinary moments of ordinary people: Sharon “Tobi” Stone, who said little but hit that cowbell hard in Cobb’s R&B band, Black Velvet; Free movie tickets for the kids in the hands of Patty Cartmell, who could talk her way into anything; Marceline Jones’s love of burnt toast.

0 notes

Text

Wednesday’s meeting of presidents Joe Biden and Xi Jinping at Filoli adds even more history to the fascinating and illustrious Bay Area mansion. Although this meeting will certainly have more geopolitical implications, a moment captured in Filoli’s library 42 years ago changed pop culture forever.

...

With his fortune, Bourn built or bought some of the most beautiful homes in California and Ireland: Villa Eden Del Mar on Pebble Beach’s 17-Mile Drive, Bourn Mansion at 2550 Webster St. in San Francisco, Muckross House in Killarney, Ireland, and Filoli in Woodside. The pseudo-Italian name was a mashup of letters from Bourn’s credo: “Fight for a just cause. Love your fellow man. Live a good life.”

After William and wife Agnes’ deaths, the mansion was bought by Lurline Matson Roth, the heiress to the Matson shipping empire. Due to the immense costs of maintaining the estate, the mansion was in decline when Roth gifted it to the National Trust for Historic Preservation in the 1970s. It was restored and opened to the public for tours.

...

But its true star turn came in 1981 when a new soap opera called “Dynasty” shot its three-episode pilot there. The sexy, scandalous lives of the Carrington family unfolded in their Denver mansion, which was actually Filoli. Stars John Forsythe, Linda Evans, Pamela Sue Martin and Al Corley filmed in the home and gardens, including a scene in the Filoli library that would make television history. It was there that son Steven Carrington came out to patriarch Blake Carrington, making Steven the first openly gay lead on a primetime drama.

0 notes

Text

40K notes

·

View notes

Text

Silicon Valley is notorious in the global economy and the American psyche. According to author Malcolm Harris, the Bay Area tech hub and California at large are a laboratory for the worst consequences of capitalism–centuries in the making. Harris unpacks this theory in his book “Palo Alto: A History of California, Capitalism, and the World.” He joins Kai to dig into the global history of Silicon Valley and his upbringing in the region.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Richard Oakes was the face of the burgeoning “Red Power” movement when he led the famous Native occupation of Alcatraz Island in 1969.

But like other civil rights leaders at the time, he died too soon. In 1972, Oakes was gunned down in rural Sonoma County. His killer, Michael Oliver Morgan, stood trial for manslaughter and was found not guilty.

The official story of Richard Oakes’ death, and the circumstances surrounding Morgan’s trial, are part of the reason why Oakes’ legacy has been largely erased from mainstream history. Oakes’ family and friends, meanwhile, never got closure. All this time, they have believed that Oakes’ death, and Morgan’s acquittal, were racially motivated.

Now, thanks to new reporting from the San Francisco Chronicle, we know details about this story that have been kept secret for decades. In Part 1 of a two-part episode with reporters Julie Johnson and Jason Fagone, we discuss the events that led Oakes to rural Sonoma County, and the encounters that foreshadowed his killing.

0 notes

Text

Cee told me that they believe that people go to Burning Man because they experience “something transformative” — the same thing that “deep meditators” and “people on mushrooms” experience. They call it “pure consciousness experience.”

“You can have that anywhere,” they told me. People think they have to purchase a $700 ticket and travel hundreds of miles, they said, “but that's an illusion.”

It’s hard not to wonder if “Burning a Man,” in its DIY, trademark-dodging glory, channels the original spirit of Burning Man. The event started out as a beach gathering in the 1980s — only a few miles away from the site of “Burning a Man,” at Baker Beach. Like the original Burns, “Burning a Man” is unofficial, unauthorized, and unregulated.

In the future, “these regional burns will take over,” said Marshall Smith, 77, a retired city employee living in Russian Hill. “I think the whole thing in Nevada’s getting unsustainable, so you’ll see more of this going on all over the place.”

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

A flapper looks out at Pacific Ocean Park in Santa Monica sometime in the mid-1920's.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

23K notes

·

View notes

Text

A luxury four-star resort on San Diego’s Mission Bay shoreline has been accused of suppressing public access to a beautiful stretch of California sand.

A California Coastal Commission report reviewed by SFGATE accuses Paradise Point Resort of numerous violations that “impede public use of the area and reinforce the impression that the entire area was private.”

The 44-acre site and half-mile stretch of white sand surrounding Vacation Isle, in the middle of the city’s giant human-made aquatic park, have always been open to the public, but visitors could be forgiven for thinking the area was private due to encroachment from the hotel and spa, the commission says. Alleged violations included the failure to put up a single “public access” sign, blocking public pathways to the beach, and the installation of a kiosk and security guard at the primary parking entrance. Another allegation states that the resort built or placed uncovered dumpsters and an event tent on public pathways and parking spots.

1 note

·

View note

Text

What most people in the Bay Area already know is that the city moved the vast majority of its dead to Colma in the 1930s. That, at least, is the common narrative. What Winegarner uncovers here is a far more shocking tale — one in which San Francisco remains awash with dead bodies that are simply lacking grave markers. And we’re not just talking about the handful that have popped up over the years during construction work.

The bodies that were moved to Colma came from San Francisco’s four main cemeteries — Laurel Hill, Masonic, Odd Fellows and Calvary — all of which were positioned on the north side of the city. However, San Francisco’s Forgotten Cemeteries thoroughly charts all of the other places that city dwellers once used as graveyards — and many are in unexpected, and under-discussed, locations. Dolores Park, for example, was a Jewish cemetery. Russian Hill is named for the fact that Russian sailors were buried there in 1848. Bodies were buried at First and Minna downtown. Most shockingly of all, Civic Center was once home to an enormous cemetery named Yerba Buena. (And a smaller one known as Green Oak.)

The Yerba Buena graveyard started at Market and Larkin and stretched all the way up to where City Hall stands today. It was opened in 1850, contained an unmarked mass grave of 800 bodies moved from North Beach, and was filled with between 7,000 and 9,000 bodies within the first eight years of its existence. In 1868, the dead were disinterred and moved again — at least, they were supposed to be. In truth, hundreds of bodies were left behind, under what is now Civic Center Plaza, City Hall, the Asian Art Museum and the Library.

According to Winegarner, few corners of the city are actually free of former residents’ bodies. Keep in mind that the Mission Dolores graveyard once contained between 10,000 and 11,000 bodies. And while only 200 or so are marked by gravestones today, thousands of dead remain under 16th Street and the surrounding buildings, many of them the Indigenous people who built the mission in the first place.

1 note

·

View note

Text

At the outset of Chloe Sherman’s new photography book Renegades, there are three forewords. One by fellow photographer Catherine Opie, one by writer (and former Blatz vocalist) Anna Joy Springer, and one by Tribe 8 vocalist and author Lynn Breedlove. All pay tribute to Sherman’s disarming photographic style and her knack for preserving everyday moments in queer Bay Area history. Breedlove’s words, however, go one step further, viscerally reveling in the memory of what it was to be young, rebellious and queer in 1990s San Francisco.Chloe Sherman’s ‘Renegade’ Photography Captures ’90s Queer Culture in SF

“We came from around the country and the planet, tired of the crusades to be seen and not killed, from rural places, big cities,” Breedlove writes. “Even NYC and LA looked askance at our out-of-line gender assertions, as we stabbed flags into the dirt, some of us already transitioning, adopting pronouns, audaciously insisting we were gorgeous, terrifying, trifling with normativities, flying in the face of cisterns, tossing dynamite at binaries, then rebuilding ourselves from the bits.”

0 notes

Text

By looking west to California, Jean Pfaelzer shifts our understanding of slavery as a North-South struggle and focuses on how those who were enslaved in California fought, fled, and resisted human bondage. In unyielding research and vivid interviews, Pfaelzer exposes how California's appetite for slavery persists today in the trafficking in human beings who are lured by promises of jobs but who instead are imprisoned in sweatshops or remote marijuana fields, or are sold as nannies or sex workers.

Pfaelzer relates the history of slavery in California across its entire spectrum, from indentured Native American ranch hands in the Spanish missions, children sent to Indian boarding schools, Black miners, kidnapped Chinese prostitutes, and convict laborers to the victims of modern human trafficking, and she argues that California owes its origins and sunny prosperity to slavery. Spanish invaders captured Indigenous people to build and farm the chain of Catholic missions. Russian otter hunters shipped Alaskan Natives down to the California coast—the first slaves to be transported to California. The Russians also launched the Pacific slave trade with China. Southern plantation slaves were marched across the plains to help their owners mine during the Gold Rush. San Quentin Prison was the incubator for California’s carceral state. Kidnapped Chinese girls were sold to caged brothels in early San Francisco. And Indian boarding schools supplied farms and hotels with unfree child workers.

Pfaelzer's provocative history of slavery in California could rewrite people's understanding of the settling of the West, and redefine the actual paths to eventual freedom for many Americans.

0 notes

Text

The story of San Francisco is a tale not of two cities, but a constellation of physical and cultural landscapes that overlap yet feel distinct.

Now more than ever.

The media narrative in recent months has focused so intently on the crises in areas like the Tenderloin and Union Square that outsiders might think all 49 square miles had spun downward into a cesspool of crime-plagued streets and drug bazaars.

But for most of the city, the nooks and crannies and neighborhood scenes, the story is more complex. Even the smallest crossroad has its own identity, shaped by historic and social forces that leave clues in the built terrain around you.

Think of San Francisco, then, as a mosaic of realities that reveal their connections the more closely you look. Here are six vignettes that hint at the facets of this nuanced place — and how even in a city of neighborhoods, the whole can be greater than the sum of the parts.

0 notes