Text

Resisting Silence through Music: Asian Diaspora & Queer Identities

“I had supposed that I was practicing passive resistance to stereotyping, but it was so passive no one noticed I was resisting. To finally recognize our own invisibility is to finally be on the path toward visibility. Invisibility is not a natural state for anyone” (Mitsuye Yamada, 1979). In Invisibility is an Unnatural Disaster: Reflections of an Asian American Woman, Mitsuye Yamada urges Asian American women to strive toward visibility and resist the pressure to remain silent about their lived experiences. We wish to explore how Asian immigrants have navigated their multicultural and queer identities through music. In the United States and other Western countries, musicians with Asian ethnicities and heritage are often “othered,” with the label of “perpetual foreigner” imposed on their image, even if they have lived in the United States their entire lives. Here are some examples of musicians in the Asian diaspora who use their voices and music to affirm their Asian and queer identities, however they wish to define it.

undefined

youtube

1. Ruby Ibarra

Ruby Ibarra is a Filipina-American rapper who immigrated with her family from Tacloban City, Philippines to San Lorenzo, California. Living in the Bay area where hip-hop was a formative element of her childhood and adolescent years, Ibarra raps in Tagalog (Filipino language) and English. Through music she speaks about growing up with the colonial mentality of whitewashing, growing up as an immigrant family assimilating to US culture, and reclaiming pride as a filipina. She has said that she does not attempt to represent or define the immigrant experience for every individual, but that “[she] hopes people find moments in these songs where they feel represented.” As a non-black POC whose music largely focuses on the genre of rap music, there is definitely room to argue the nuances of using black culture for her music. It seems like Ibarra has taken steps to address this issue—on her social media platforms like instagram, she often gives tribute/credit to the black community: “I recognize my privileges as a non-black POC, and the beautiful culture and genre of music I’ve been able to participate in that was created by the black community.” (instagram post from February 1, 2018). She also takes action as an ally to use her platform in speaking out against police brutality: “Police (and media) typically justify the shootings by saying they were armed-- does being black cancel the right to bear arms? ...We need a system that doesn’t target a group of people. We need a system that doesn’t kill a group of people...The long history of system racism has led to mistrust and fear of law enforcement.” (instagram post from September 21, 2016).

Listen to her album Circa91. I recommend “Brown Out,” “Someday,” and “Us.”

undefined

youtube

2. Rina Sawayama

Rina Sawayama is a Japanese-British R&B pop musician. She was born in Niigata, Japan and immigrated to London, England with her family when she was 5 years old. In a 2018 Broadly interview, Zing Tsjeng describes Sawayama’s character as a “tangerine-haired, cyberpunk-influenced musician slash model.” A central theme that Sawayama explores in her music is romance and alienation in the internet-obsessed society that we live in.

In “Cherry,” Sawayama takes the opportunity to publicly vocalize her pansexual identity. She describes the song as her most personal but political song, and has contemplated past moments of shame around her queerness. For Sawayama, “Cherry” is a love letter of affirmation for bi and pan people who don’t feel authentically queer when they’re heterosexual relationships <3 <3 <3

During her studies at Cambridge in England, Sawayama felt alienated, different, and undesirable in an environment where over 60 percent of its student population is white and British. Later in life, Sawayama has found communities and families as she has continued her journey as a musician. She has spoken about the many emerging queer Asian artists active in many different genres: “We’re so protective of our space, even who we decide to sign to, who we decide to release through, or who we decide to work with. It’s really important to us. Because as queer Asians, there’s not that many of us and we really want to get it right.” To Sawayama, it’s important to her that she’s representing queer Asians, rather than just ‘Asian’. She wants to queer the world with pop music.

undefined

youtube

3. Japanese Breakfast

Michelle Zauner is a Korean American musician who takes the name Japanese Breakfast for her musical project that emerged as a way for Zauner to navigate her grief and memory of her mother’s terminal illness and death. Through music Zauner has found healing as well as a way to reckon with her Korean American identity. In the New Yorker essay “Crying in H Mart,” Zauner speaks about the identity crisis of losing her mother, who is her last connection to her Korean heritage.

Growing up in Eugene, Oregan, a predominately white town, Zauner hated being half Korean. She could barely speak the language and didn’t have any Asian friends. There was nothing about herself that felt Korean, except when it came to food. She has written an essay called “real Life: Love, Loss, and Kimchi” about the comforting power of food as a device of healing through her mother’s struggle with cancer.

On the moniker “Japanese Breakfast”, Zauner wanted a name that combined elements of something iconically American (breakfast) with something “American people just associate with something exotic or foreign” (Japanese). People often assume she’s Japanese, and Zauner says that she can tell who that real fans are—they know she’s Korean. She likes that the moniker exposes those who assume she’s Japanese.

Listen to her albums Psychopomp and Soft Sounds from Another Planet for trips of nostalgia and longing and contemplation on life and death and love and grief around identity and family <3 <3

undefined

youtube

4. Hayley Kiyoko

Hayley Kiyoko is a Japanese-American singer, songwriter, actress and director who was born and raised in Los Angeles, California. She has shown interest in music as early as 5 to 6 years of age when she got her first drum kit and wrote her first song. It was also around this age that she knew that she liked girls.

Since she was young, Kiyoko has combated the loneliness that comes with being a queer asian in society. She worked as an actress during her childhood, exposing her to discrimination due to her biracial physical appearance. Several rejections due to her appearance was enough to plant the seeds of doubt about whether she was enough. In addition, she kept her sexual orientation to herself in fear of being ostracized even further—only coming out to her parents in sixth grade. Unfortunately, her parents refused to acknowledge this confession, stating that it was just a phase.

She continued to keep her sexual orientation a secret which isolated her even further from her friends. She found it depressing to watch girls that I liked flirt with guys, so she stayed at home during her free time. Later on, she had her heart broken by her best friend which devastated her for a period of time. The constant rejection that Kiyoko had received until then prevented her from being comfortable with who she was, putting her in a state of perpetual fear.

In order to appeal to more of an audience, her songwriters wanted her to sing about topics that she personally connected to. As a result, she came out to her songwriters which inspired “Girls Like Girls,” a song that referenced her experience as a lesbian. Also, in putting out music videos that actually show the narrative that she sings about, she fights the heterosexual narrative that restricts the LGTBQ community in today’s society. Using her music as vehicle of representation, she unites a group of isolated individuals, earning her the nickname “Lesbian Jesus.”

By confronting her past fears and illustrating them in a form with which she loves and performs, she becomes the idol that she never had.

0 notes

Text

The First Asian American Anthology

Aiiieeeee! An Anthology of Asian-American Writers by Frank Chin, Jeffery Paul Chan, Lawson Fusao Inada, Shawn Wong and others is one of the earlier pieces of Asian American literature, produced in 1974 by Combined Asian Resources Project (CARP). The text helped Asian American literature get recognized as a category of its own in the 1970s. According to Wikipedia:

“This anthology collected staples of long-forgotten Asian American literature [from Chinese -, Japanese-, and Filipino-Americans from the past fifty years], and criticized the lack of visibility of this literature. This anthology brought to light the necessity of visibility and criticism of Asian American literature.”

By recovering works of previous generations of Asian American authors, such as Sam Tagatac, Toshio Mori, Carlos Bulosan, Diana Chang, Louis Chu, Momoko Iko, Hisaye Yamamoto, and many others of whom are now staples in Asian American literature courses, Asian American literature gained new exposure and publication. Prior to the publication of this anthology, there was a serious lack of visibility and criticism of Asian American literature. Again, according to Wikipedia:

“One of the defining features of CARP's anthology touched upon stereotypes of Asians as a whole: how published work did not receive criticism because the writing did not line up with racial views. This anthology paved a way for authors to write and express feelings of individual identity and crisis concerning racism. The anthology helped in the fight against cultural assimilation, which played a large role (model minority being the biggest example) in the day-to-day life of Asian Americans.”

In the interest of relating this text to North Asian American Feminisms, what is most interesting about this anthology is that it aims to bring forth the stories about the Asian American experience that does not subscribe to stereotypes. More specifically, the anthology is notable for its opening essay, “Fifty Years of Our Whole Voice,” which defines the editors’ understanding of what constitutes a “true Asian American sensibility.” That is, CARP claims the true Asian American experience is non-Christian, non-feminine, and non-immigrant.

“These stances have been controversial, especially after the rise of Asian American women's literature (Maxine Hong Kingston, Amy Tan, et al.) and the change in Asian American demographics in the 1980s, when more Asian American writers were immigrants (e.g., Bharati Mukherjee) and/or from other Asian cultures (e.g., Korean, Indian, Vietnamese).” - Wikipedia.

These views are incredibly problematic, because they exclude a huge group of people who identify as Asian American and who have stories to add to the larger collective narrative of the Asian American experience. Namely, stories coming from lesser privileged groups within the Asian American community such as South and Southeast Asians, queer Asian folk, and Asian women in general. If we choose to ignore non-Christian, non-feminine, and non-immigrant Asian stories, we fall into the trap of believing there is only story, which can lead to a harmful invisibility of issues of certain demographics within our community, as well as perpetuate the idea that Asian America is mono-racial and monocultural.

In reality, according to “Possibilities of a Multiracial Asian America” by Yen Le Espiritu:

“Asian American, by definition, is multiracial [and multicultural] and that this multi-raciality [and multi-culturality] provide us the critical space to explore the strategic importance of cross-group affiliation -- not only among Asians but also with other kin groups.”

Nevertheless, it is important to recognize the impact of this anthology, as it truly brought more attention to Asian American writers and their stories and helped establish Asian American literature as a force to be reckoned with.

If anything, this anthology most definitely raises the questions that will continue to plague the category until today: What is Asian American literature? What counts as Asian American literature? Who gets to write Asian American literature? Who is an Asian American? Can Asian America literature include texts from the rest of the Americas or is it exclusively for the United States? If an Asian American writes about characters who are not Asian American, is their story part of the Asian American literature canon?

Clearly, the themes of race, ethnicity, and identity play a huge role in Asian American literature.

Sources:

Espiritu, Yen Le, et al. “Possibilities of a Multiracial Asian America.” The Sum of Our Parts: Mixed Heritage Asian Americans, Temple University, 2001, pp. 25–33.

“Aiiieeeee! An Anthology of Asian-American Writers.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 29 Aug. 2018, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aiiieeeee!_An_Anthology_of_Asian-American_Writers.

“Asian American Literature.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 15 Mar. 2019, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Asian_American_literature.

0 notes

Text

3 Asian American Writers Speak Out on Feminism by Mitsuye Yamada, Merle Woo, and Nellie Wong

3 Asian American Writers Speak Out on Feminism by Mitsuye Yamada, Merle Woo, and Nellie Wong is an Asian American anthology on various cultural writings and Asian American studies that relate to feminism written by three Asian American female writers.

The collection contains poems, personal essays, fictional and nonfiction stories, a book review, and an academic article. What is so unique about this particular anthology is that it explores themes and issues relating to Asian American women, namely: concepts of the intersectionality of race, gender, and sexuality, the struggle to create when in struggle, the Asian American community as a whole, the double-edged sword of stereotypes for Asian American women (especially between the demure, submissive doll and the exotic, dangerous other), and the danger that comes with the invisibility of Asian American women’ stories.

It is the latter issue that deserves some attention, though the entire anthology is incredible in its scope and diverse writing, and everyone should read the entire thing. The anthology itself doesn’t take long to read; it’s only 48 pages.

From the publisher:

“Cultural Writing. Asian American studies. "I had supposed that I was practicing passive resistance to stereotyping, but it was so passive no one noticed I was resisting. To finally recognize our own invisibility is to finally be on the path toward visibility. Invisibility is not a natural state for anyone"-from 3 ASIAN AMERICAN WRITERS SPEAK OUT ON FEMINISM.

In the interest of relating this to WMST 4070: North Asian American Feminisms, what is so interesting and honestly, powerful about this anthology is that while it continues the tradition of Asian American literary anthology work started by one of the first Asian American anthologies “Aiiieeeee! An Anthology of Asian-American Writers,” it almost directly puts itself into conversation with this anthology by specifically including only texts that revolve around Asian women, which Aiiieeeee! had not included when it was first published in 1974. Moreover, this text was also published relatively not much later after Aiiieeeee!: 3 Asian American Writers Speak Out on Feminism was published in 1986. Therefore, it is clear that Yamada, Woo, and Wong used the concept of the anthology, an important literary format for Asian American literature, to make public the ideas and issues that populate Asian American women’s lives, as well as to connect with other Asian Americans. This desire to connect, to link up, to unite, can be a powerful tool of resistance against the patriarchy and white supremacy.

“Writing is a public act, the pulse and heartbeat of our lives...Writing for [us] is really the touching of hands between sisters, between sisters and brothers in an oh so human world. It is the link between our physical and spiritual realities, the celebration of our past and present lives, and ... a working vision for the future.” - (Wong 18).

The act of writing down and storytelling give these three Asian American women a tool to resist this blatant exclusion of their stories by mostly Asian American men. Furthermore, these three women have carved themselves a space in Asian American literature that allows them to “take action toward personal and social change instead of drowning in a sea of self-doubt” (Wong 19).

To buy on Barnes and Noble

Goodreads reviews

Sources:

Yamada, Mitsuye, et al. “Glows from the Dark of Monsters and Demons: Notes on Writing.” 3 Asian American Writers Speak Out on Feminism, Radical Women Publications, 2003, pp. 16–19.

“Three Asian American Writers Speak Out on Feminism.” Amazon, Amazon, 1 Jan. 2003, www.amazon.com/Three-Asian-American-Writers-Feminism/dp/0972540350.

0 notes

Text

Author Highlight #1: Maxine Hong Kingston

Maxine Hong Kingston is a Chinese American author and Professor Emerita at the University of California, Berkeley, where she graduated with a BA in English in 1962. Kingston has written three novels and several works of nonfiction about the experiences of Chinese Americans. Her most notable work, the one that most famous contributed to the feminist movement, is The Woman Warrior.

The Woman Warrior: Memoirs of a Girlhood Among Ghosts is a book that blends Kingston’s autobiography and old Chinese folktales to discuss gender and ethnicity and how these concepts affect the lives of women. This book is routinely taught in Asian American literature classes, Asian American feminism classes, women’s studies classes, and multicultural American literature classes, among many other spaces.

Published in 1976, The Woman Warrior won the National Book Critics Circle Award and was named one of Time magazine’s top nonfiction books of the 1970s.

It would be remiss to talk about Asian American literature and its history without discussing the impact of Kingston and The Woman Warrior on the Asian American literary canon. Once Asian American literature became recognized as a legitimate literary field, Kingston was quickly recognized as one of its most important figures. Her work helped reveal the hardships of Chinese women and Chinese American women settling in American culture, garnering more empathy and understanding for Chinese Americans.

Her impact is a beautiful example of the power of Asian American literature. By writing about her specific story and providing a voice to many nameless and voiceless Asian women, she re-centers them. That is:

“Re-centering women allows us to hear the voices of the majority of humankind -- women’s names and their “quiet odysseys” have shaped our collective past and destiny” - (Okihiro 91-92).

Furthermore, by focusing on multigenerational conflict and relationships between Asian women in America in her book The Woman Warrior and the power of talk-story,

“...despite her mother’s admonition - ‘you must not tell anyone’ -- the narrator, through the author Kingston, transcribed an oral tradition onto pages of paper, and the story of the ‘no name woman’ was passed on from mother to daughter, from one generation to the next. In truth, calls for recentering women are necessary only because of historians’ narrow chauvinism. Women have long known themselves to be at the center. And that claim cannot be denied.” - (Okihiro 92).

Here is an interview from Kingston herself, discussing her desire to visibility and bringing Chinese American female stories to life through her work.

youtube

Her books can be bought at Barnes and Noble and wherever books are sold.

Goodreads profile on Kingston.

Sources:

Okihiro, Gary. “Recentering Women.” Margins and Mainstreams: Asians in American History and Culture, University of Washington Press, 1994, pp. 64-92. WMST 4070 Course Packet.

“Maxine Hong Kingston.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 11 Mar. 2019, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Maxine_Hong_Kingston.

“The Woman Warrior.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 17 Aug. 2018, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Woman_Warrior.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Author Highlight #2: Amy Tan

Amy Tan is a Chinese American author of The Joy Luck Club, which explores mother-daughter relationships and the Chinese American experience. She is most known for this book, as it received the film adaptation treatment in 1993 and went on to become one of the first Hollywood films with an all Asian American cast.

According to Wikipedia:

“Tan has written several other novels, including The Kitchen God's Wife, The Hundred Secret Senses, The Bonesetter's Daughter, Saving Fish from Drowning, and The Valley of Amazement. Tan's latest book is a memoir entitled Where The Past Begins: A Writer's Memoir (2017).[1] In addition to these, Tan has written two children's books: The Moon Lady(1992) and Sagwa, the Chinese Siamese Cat (1994), which was turned into an animated series that aired on PBS.

The Joy Luck Club (1989) consists of sixteen related stories about the experiences of four Chinese American mother-daughter pairs and/or immigrant families in San Francisco who start a club known as The Joy Luck Club, playing the Chinese game of mahjong for money while eating a variety of foods.

“Despite her success, Tan has also received substantial criticism for her depictions of Chinese culture and apparent adherence to stereotypes.” - Wikipedia

More specifically, The Joy Luck Club has received criticism for perpetuating racist stereotypes about Asian Americans and depicting Chinese culture as backwards, cruel, and misogynistic. One of the biggest critics of the text is Frank Chin, one of the primary editors of the Aiiieeeee! An Anthology of Asian-American Writers (1974) anthology.

“He attributed the acclaim and popularity of The Joy Luck Club to playing up racist stereotypes welcomed in mainstream America. He also noted that it lacks authenticity for its fabricated Chinese folk tales that depict ‘Confucian culture as seen through the interchangeable Chinese / Japanese / Korean / Vietnamese mix (depending on which is the yellow enemy of the moment of Hollywood.’” - Wikipedia

What is interesting and ironic about this take is that it calls into the issue of the complex intertwining of the problems of race, gender, and class for Asian Americans. That is, yes, “the racial and class oppression against ‘yellows’ restricts their material lives, (re)defines their gender roles, and provides material for degrading and exaggerated sexual representations of Asian men and women in U.S. popular culture” (Espiritu 24). There is a real issue of pervasive stereotypes plaguing the depiction of Asian Americans in media and in literature. Therefore, it is important for Asian Americans to resist “race, class, and gender exploitation through political, economic, and cultural activism” (Espiritu 24). However, in attempts to demand legitimacy, “some Asian Americans have adopted the either/or dichotomies of the dominant Eurocentric patriarchal structure, ‘unwittingly upholding the criteria of those whom they assail’” (Espiritu 24). That is, Asian Americans tend to use the oppressor’s tools to oppress each other in attempts to find agency and power in a world that marginalizes them.

For instance, having been emasculated by white men, Asian American men “seek to reassert their masculinity by physically and emotionally abusing those who are even more powerless -- the women and children in their families” (Espiritu 24). This can be seen in the way Chin and other Asian American male writers try to police Asian American women and their writing. They present a dichotomy where Asian American women are forced to pick between race and gender to prioritize. In other words, “some Asian American political and cultural workers have subordinated feminism to nationalist concerns” (Espiritu 24). “The Asian American men who can see only race oppression, and not gender domination, are unable -- or unwilling -- to view themselves as both oppressed and oppressor” (Espiritu 24). As a consequence, this stance has led to the marginalization of Asian American women and their needs. “The racist debasement of Asian men makes it difficult for Asian American women to balance the need to expose the problems of male privilege with the desire to unite with men to contest the overarching racial ideology that confines them both” (Espiritu 25).

This is why it is important for Tan to have written a text that revealed the harsh realities of Chinese American women in The Joy Luck Club, especially with the critique on the patriarchy and the depiction of certain stereotypes. There are many stories that Asian Americans can tell about themselves and about others. This just so happens to be Tan’s story and readers should not silence her voice.

I believe it is important to tell all kinds of stories, to have a huge diverse literary canon for the Asian American experience, in order to prevent one story from becoming the Universal story, which can result in more perpetuation of stereotypes.

Her books are sold at Barnes and Nobles and wherever books are sold.

Tan’s Goodreads profile.

Sources:

Espiritu, Yen Le. “Race, Class, Gender in Asian America.” Making More Waves, 2019. WMST 4070 Course Packet.

“Amy Tan.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 3 Apr. 2019, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Amy_Tan#Work_and_themes.

“The Joy Luck Club (Novel).” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 24 Apr. 2019, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Joy_Luck_Club_(novel).

0 notes

Text

Author Highlight #3: Jenny Han

Jenny Han is a Korean American young adult author of the To All The Boys I’ve Loved Before trilogy and the The Summer I Turned Pretty trilogy. She is most known for the former trilogy, as the first book of the same name has been adapted for a movie on Netflix starring Lana Condor and Noah Centineo.

According to Wikipedia:

“In 2014, Han released a young adult romance novel, To All the Boys I've Loved Before, about Lara Jean Song Covey, a high school student whose life turns upside down when the letters she wrote to her five past crushes are sent out without her knowledge.[7] The novel was optioned for a screen adaptation in the weeks following its debut.[8] The sequel, P.S. I Still Love You, was released the following year, and won the Young Adult 2015–2016 Asian/Pacific American Award for Literature.[9] A third novel, Always and Forever, Lara Jean, was released two years later.[10] The film adaptation of the first novel, starring Lana Condor in the lead role, began filming in July 2017 and was released by Netflix in August 2018, to positive reviews.”

To All The Boys I’ve Loved Before is an incredibly important book in the Asian American literary canon, particularly within Young Adult Literature, due to its focus on a young Korean American girl who gets to fall in love and do normal American girl things. This book changed the game, because it was the first time many young Asian American girls saw themselves in a book character. Lara Jean allowed them to believe that they too can fall in love and that their existence as an Asian American can be universal and related to.

The importance of representation in young adult literature specifically, cannot be understated. When young people, particularly young teens of color, see themselves and their experiences reflected in the literature, they feel validated and seen. There is a sense of empowerment that comes with this type of representation. And when teens are empowered, they can change the world. With more than 300,000 ratings and a 4.16 starred rating on Goodreads, To All The Boys has become one of the most popular and beloved young adult books of all time. Even prior to the movie’s release.

In regards to the movie, Jenny Han worked for years to get it optioned and made into a movie, but with one condition: the lead had to be played by Asian American girl. That one condition made it hard for the movie to be made because no one in Hollywood believed that a movie starring an Asian American girl would make any money or gain any views. In fact, in an interview with Teen Vogue, Han says some Hollywood Execs tried to whitewash the move:

“Yes [to the producers suggesting that they change the lead to a white woman]. Not with the people I ended up working with, but early on, the same thing happened. To me, the more alarming part of it was that people didn’t understand why that was an issue.”

Jenny Han continues by emphasizing the importance of seeing Asian American representation on film and TV:

“With Asian-Americans actors, specifically, there’s been fewer opportunities for them in TV and film, and fewer that have the ability to actually make a career out of it. It becomes a bit of a chicken and egg situation, where they’re like, “Oh, but they’re not famous names,” but they haven’t had a chance to be in anything yet, either. You want to give people a chance to grow and evolve as well.”

Clearly, the fight for Lara Jean to be played by an Asian American woman paid off, because the Netflix adaptation that stars Lana Condor went on to become one of the most watched original Netflix movies of all time, with over 100 million repeat watchings on the streaming platform.

In addition, Lara Jean inspired dozens of fabulous Halloween costumes, exemplifying the power of representation and how it can impact an entire generation of Asian American women.

In a tweet, Han says:

“There are very limited options for Asian girls on Halloween. Like one year I went as Velma from Scooby-Doo, but people just asked me if I was a manga character.” Not this Halloween, Lara Jean 👻”

With the inclusion of some amazing photos:

I also can’t help but include my own pictures of cosplay as Lara Jean:

Jenny Han’s literature has changed my life and impacted me in more ways than one. I am personally so grateful to be living in a time where I can see Asian American girls in the books I read and the movies I watch.

Han’s books are sold at Barnes and Nobles and wherever books are sold.

Goodreads profile on Han.

Sources:

@flaw_estley. Twitter, 29 Oct. 2018, twitter.com/flaw_estley/status/1056960783257690112/photo/1?ref_src=twsrc^tfw|twcamp^tweetembed|twterm^1056960783257690112&ref_url=https://mashable.com/article/lara-jean-jenny-han-halloween-costumes/.

@nicoolehe. Twitter, 27 Oct. 2018, twitter.com/nicolehe/status/1056307355552546816/photo/1?ref_src=twsrc^tfw|twcamp^tweetembed|twterm^1056307355552546816&ref_url=https://mashable.com/article/lara-jean-jenny-han-halloween-costumes/.

Foreman, Alison, and Alison Foreman. “The Author of 'To All the Boys I've Loved Before' Has the Purest Reaction to Everyone's Lara Jean Halloween Costumes.” Mashable, Mashable, 29 Oct. 2018, mashable.com/article/lara-jean-jenny-han-halloween-costumes/.

Han, Karen. “Jenny Han Says Some Hollywood Execs Tried to Whitewash ‘To All the Boys I've Loved Before," Too.” Teen Vogue, Teen Vogue, 16 Aug. 2018, www.teenvogue.com/story/jenny-han-interview-to-all-the-boys-ive-loved-before-movie.

“Jenny Han.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 1 Apr. 2019, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jenny_Han.

0 notes

Text

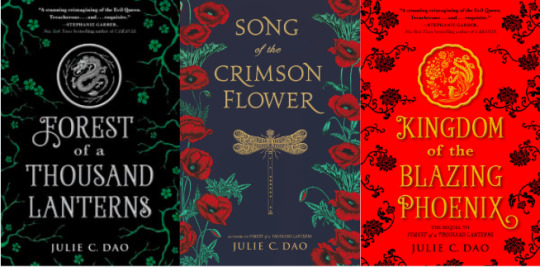

Author Highlight #4: Julie C. Dao

Julie C. Dao is a Vietnamese American young adult author of Forest of A Thousand Lanterns, Kingdom of The Blazing Phoenix, and Song of the Crimson Flower. She is known for her retellings of classic fairytales such as the rise of the Evil Queen and the story of Snow White with an East Asian flare. Her soon to be released book Song of the Crimson Flower is a young adult fantasy novel about Vietnamese characters and folklore.

To start off, I want to mention that the first two books Dao have written -- FOTL and its sequel KOBP -- have Chinese main characters and the soon to be released book SOCF has Vietnamese main characters. In an interview with Bustle, Dao says for FOTL at least:

“I combined multiple elements that shaped me as a person and a writer. I loved classic fairytales growing up, which is where Snow White comes in, and blended that with East and Southeast Asian folktales I grew up reading or hearing from my parents...I chose an Imperial Chinese-inspired setting for my mother, who loves epic dramas and miniseries set against that backdrop, and for whom this book was written. And, of course, I love powerful female characters and complex antiheroes. Put those together and you get Forest of a Thousand Lanterns."

What we can glean from this quote is that it is clear Dao, a Vietnamese American, has grown up reading and watching Chinese inspired stories. As a second-generation daughter of immigrants and a product of diaspora, she has combined her love for classic English literature and Chinese mythology, the west and the east, two incredibly influential aspects of her identity as an Asian American, to create her book. However, when FOTL was first published in 2017, Dao was heavily criticized by Chinese readers for “appropriating Chinese culture” in her book. What was interesting about some of the criticism was that it mostly came from mainland Chinese readers, and not Chinese Americans. It was very clear, early on, that mainland Chinese readers did not understand the very big representation problem of Asians in the publishing world in America, that there was a desire to police Dao’s work. There was a very clear power hierarchy being reinforced with the criticism heading towards Dao, in that Chinese readers were criticizing a Vietnamese American woman for being inspired by works that she was surrounded by as a child due to imperialism. Therefore, it is crucial to analyze the criticism of FOTL and Dao with a nuanced lens and an awareness of the history of Chinese imperialism on Southeast Asian countries like Vietnam.

Another issue that came up with FOTL was the question of why Dao hadn’t written about Vietnamese characters instead? I take issue with this criticism because it goes back to policing writer’s works, particularly Asian American female writers’ works. With the rise of diversity campaigns such as We Need Diverse Books and the push for own voices books, there has been a real boundary being placed around the type of stories marginalized writers are able to tell. In that, in the publishing world’s effort to push for marginalized writers to write about stories inspired by and about their identities and marginalized upbringings, it has end up preventing marginalized writers from ever going beyond the boundaries of their own identities. In other words, marginalized writers are being told they can only write what they know, which is ironic because white and other privileged writers are not held to the same standard. Dao has fought back against her critics and pushed for her ability to write about the stories that have inspired her as a child, namely stories about powerful women, who also happen to be Asian. In the same interview with Bustle, Dao says:

“Some of the deepest, most profound relationships in my life have been shared with other women. In addition to the romance, I wanted to explore familial and platonic bonds between women because they can be some of the strongest you’ll ever find, yet also fragile and delicate at times," Dao says. "I wanted a cast of well-rendered women, each strong in her own way. Human relationships can be complicated and messy, and I wanted to portray this in all of the female bonds and conflicts I touched on in the book.”

Lastly, not all of the criticism for FOTL was unwarranted. More specifically, many Asian American readers pointed out the problem of the book’s synopsis and the pitches for the book. FOTL was routinely described as an East-Asian inspired fairytale retelling of the rise of Snow White’s Evil Queen figure. Many criticized the blanket term of East Asia being used to describe the book’s culture when it was very clear that it is very heavily inspired specifically by Chinese culture. This brings to light the issue of the term of Asian America and East Asia and how often this term is considered monolithic and all encompassing of all Asian cultures, which can lead to a harmful invisibility of lesser privileged Asian cultures such as South and Southeast Asian culture. It is important to critically analyze how we define the term ‘Asian America’ and whether there should be an all encompassing label for such a diverse group of people.

You can buy Dao’s books at Barnes and Nobles and where all books are sold.

Goodreads profile.

Sources:

Dao, Julie C. “Bio.” Julie C. Dao, www.juliedao.com/about-me/.

Jarema, Kerri. “'Forest Of A Thousand Lanterns' Is The Evil Queen Retelling You Need In Your Life.” Bustle, Bustle, 17 Dec. 2018, www.bustle.com/p/julie-c-daos-forest-of-a-thousand-lanterns-is-the-evil-queen-fairytale-retelling-you-need-in-your-life-2889978.

0 notes

Text

Author Highlight #5: Roshani Chokshi

Roshani Chokshi (Rosh-Knee Chalk-She) is the New York Times bestselling author of Aru Shah and the End of Time, The Star-Touched Queen, A Crown of Wishes, and The Gilded Wolves, among other works. Her work has been nominated for the Locus and Nebula awards, and her books have appeared on Barnes and Nobles Best New Books of the Year and Buzzfeed Best Books of the Year lists. Chokshi lives in Georgia with her husband.

Many of Chokshi’s literary works are inspired by her background as a mixed-raced Filipino and Indian American woman who grew up reading abridged, translated fairytales and books on Filipino and Indian mythology. For instance, her series with big-time bestselling author of the Percy Jackson series, Rick Riordan, and his imprint for diverse own-voices authors writing mythology for young readers called ‘Rick Riordan Presents’, Aru Shah and the End of Time, is about a young Indian-American girl named Aru Shah who accidentally unleashes the gods, goddesses, and demons of Hindu Mythology into the real world.

Chokshi, stating in a LA Times interview:

"My parents did an incredible job of inspiring me and my siblings to be voracious readers from the start...I think a large part of that is because we didn't learn our parents' native languages growing up. We only spoke English at home and so the way that we connected to parts of our heritage was oftentimes just through fairy tales and world mythology books. You couldn't really understand your own background without that."

Despite growing up with these stories as part of her heritage, Chokshi has had to do research for all of them. She says:

“I did inhale this mythology growing up, but India is such a vast country that there are so many different versions of the same tale.”

Across numerous interviews, Chokshi reiterates how she brings her personal background to these tales without changing them in a way that does not fit. Besides adding a glossary in her books to help her readers sort out the many different mythological figures, she also includes an explanation that emphasizes that her story is not intended to be a comprehensive guide to the mythology in question. She acknowledges that some people, particularly of those within the Indian and Filipino community, will and have reached out to her to claim that she has gotten something wrong. She says:

“But we should take out the word 'wrong' because when it comes to mythology, especially in Hinduism, our mythology is a living thing. It's so closely tied to our religious identity. To call something wrong is to cancel out someone else's truth."

What Chokshi talks about here regarding a person’s truth is interesting. When it comes to Asian American literature, there should not be limits as to what is included within its binds. The fact that the Asian American community can sometimes police its own members and what kind of stories they are allowed to pull from (despite being inspired by these stories as a child of immigrant and diaspora parents, which I believe gives them the right to write about) is harmful and needs to stop. By policing what kind of content other Asians are allowed to produce and what kind of stories we are allowed to tell, we inevitably use the oppressor’s tools to oppress our own people. This relates to the issues in constituting Asian-American Feminisms and how...

“Any attempt to fix definitions of...Asian-ness, more broadly, through objective racial, national, or ethnic criteria, and to impose it as a category of state regulation must be resisted because to go down that road is to go the way of endless arguments over authority, authenticity, and voice, and ultimately reproduces race consciousness and racism” - (Lee 29)

Lastly, I feel compelled to include this quote from Chokshi about the importance of representation, from Book Voyagers Blog:

“So many of the stories I loved shared characteristics that I wanted to write something that would be familiar to fairytale fans and also new because the story drew on different cultural traditions. I also felt an obligation to write this for my younger self. Growing up as a fantasy reader, I never saw people like me represented in those stories. I wanted to change that. There were times when I felt discouraged from writing The Star-Touched Queen. I felt like no one would even want to read this because it was too unfamiliar or they just had no interest. But so far I've been proven wrong in the best way possible.”

Goodreads profile

Barnes and Noble link to buy Chokshi’s books; available where all books are sold.

Sources:

Lee, Jo-Anne, et al. “Issues in Constituting Asian-Canadian Feminisms.” Asian Women, Women's Press - Canadian Scholar's Press, 2006, pp. 21���45.

“How Roshani Chokshi Came to Write a New Series for Rick Riordan.” Los Angeles Times, Los Angeles Times, 11 Apr. 2018, www.latimes.com/books/la-ca-jc-fob-roshani-chokshi-20180411-story.html.

“THE STAR-TOUCHED QUEEN: Interview with Roshani Chokshi.” The Book Voyagers, thebookvoyagers.blogspot.com/2015/12/the-star-touched-queen-interview-with.html.

0 notes

Text

Queer, Asian, and Proud

A Spotify playlist with Gaysians and Asians challenging the gender binary :)

The following artists are featured in the collage above: Of Methodist, Manila Luzon, Leo Kalyan, Thao + Mirah, MRSHLL, alextbh, and Kimmortal.

These are only a handful of the music artists featured in this 2 hr 33 min long playlist, consisting of a variety of styles (rap, indie, alternative, pop).

0 notes

Text

APAHM Heat: 88rising Takeover

A Spotify playlist with artists from and associated with 88 rising, a hybrid management, record label, video production and marketing company.

88rising was founded by Sean Miyashiro with an intention to promote Asian cultures worldwide, especially through music. Originally focused in hip hop, 88rising has ventured out of this field and has been experimenting with laidback lo-fi beats. As 88rising continues to enter different fields of music, Miyashiro wishes to create an easily accessible and relatable Asian American culture.

The following are current artists signed under 88rising (also shown above): Higher Brothers, Lexie Liu, Dumbfoundead, Joji, Rich Brian, Niki, and Keith Ape.

0 notes

Text

asian americans on the rise

A Spotify playlist consisting of rising Asian American music artists in a variety of music genres.

The following featured in the collage above only represent a few of the artists found in this playlist: Yaeji, Cosmic Child, FLANNEL ALBERT, Elephante, Robotaki, Melissa Polinar, Hana Vu, and keshi.

0 notes

Text

Mitski

Mitski is a Japanese-American indie rock singer admired for her poetic, self-deprecating, and relatable music—relatable enough to become a meme. With five albums under her belt (two which were made as her junior and senior end-of-the-year projects from The State University of New York Purchase), she has been seen as the voice of a generation riddled with anxieties. As a migrant for most of her life (she lived in at least 13 countries before settling in New York for college), Mitski has found herself dealing with issues of loneliness and permanence; even now, as she tours, she finds herself dealing with waking up to a new time zone almost every day. These issues, in addition to her challenges as an Asian American woman, have significantly affected her life and have translated into inspiration for her music.

Her most recent album, Be the Cowboy, is a collection of short songs (most no longer than two and a half minutes) in which she delves into and sings of different stories of love or the lack of it. In this album, Mitski writes several narratives of a person in or out of love: the effects of one’s own negative psyche on a relationship in “A Pearl,” the desperation of one in a marriage without love in “Me and My Husband,” the vulnerability of a limited woman in “Washing Machine Heart,” and the loneliness that comes with burning bridges and ending relationships in “Nobody.” Altogether, these fourteen songs briefly venture into different music styles of pop, soft rock, indie, alternative, and more to meld into an album that exemplifies the power of one’s emotions. The raw lyrics and backtracks of the album garnered many positive reviews along with acknowledgments as one of the top 10, 20, 50, 100 best albums of 2018 for her ‘confessional, raw lyrics.’ Be the Cowboy, titled to channel and appreciate the arrogance and confidence of the concept of the American cowboy, was also nominated for Best Recording Package at the 61st Grammy Awards.

Ultimately, Mitski’s music is upheld as an emotional staple for this generation as she can flawlessly illustrate many anxieties into her songs. While she appreciates the transition from playing to a room of no one to sold out venues, she sees a trend between her intentions with the creation of her music and her fan’s meanings for them. In an interview with Trevor Noah, she admits that she wants her fans to “get whatever they need to out of a song” for the healthiest option, but she sees this as a result of a gendered perspective. In the past, Mitski has revealed that her songs are simply inspired out of love—be it a person, a concept, or music—and not out of desire to push a certain agenda or discussion forward. By assuming and popularizing the thought that her songs are about politic stances, social justice issues, or some major existential crisis, she sees herself losing in a fight between her and her fans about her own music. Mitski explains that this is probably due to her identity as an Asian American which encourages a passive and quiet nature. Therefore, in a sense, Mitski is being ‘othered’ when it comes to her own music; ignoring her rights as the creator of her own music, her fans may unknowingly be displacing her opinions with their own on what her intentions are with a song.

For example, one of her more well-known songs, “Your Best American Girl,” depicts the reality of a relationship in which love isn’t enough to bridge the differences between partners.

Your mother wouldn’t approve of how my mother raised me // But I do, I finally do

And you’re an all-American boy // I guess I couldn’t help trying to be your best American girl

Many POC personally related to this song for its ability to single out how culture can be the dividing line in many relationships. The significance behind this chorus and the song’s narrative of ‘effort won’t always be enough to make things work’ definitely caught the attention of many people and contributed to Mitski’s current fan base. The irony, however, is that the song’s racial narrative convinced many that she wrote this song to “stick it to ‘the white boy indie rock world” when she wrote it as a love song. “I wasn’t trying to send a message. I was in love.”

Perhaps this is what encouraged her to make shorter and more vague stories for her songs on Be the Cowboy. By disconnecting her songs from her personal life and not mentioning sensitive topics like race or gender, Mitski may have aimed to be more obvious with her intentions of writing music about or inspired by love. As her fame increases among today’s society, we have to recognize that the more we idolize and assume things about her, the more likely we are restricting her in a field where she is the minority. Instead of helping her, we’re challenging her more in a way that won’t help her create music but may make her stop completely.

0 notes

Text

Music of the Asian Diaspora

A Spotify playlist consisting of a wide variety of genres by several Western Asian music artists.

The following in the collage only represent a small fraction of the artists featured in this 10 hr 13 min playlist of Asian excellence :) : Young the Giant, Mree, Vidya Vox, Qrion, cehryl, M.I.A., Us the Duo, Raveena, and eSNa.

0 notes

Text

Awkwafina

Nora Lum is a Chinese-Korean American rapper and actress, more commonly known as Awkwafina. As of recently, she has gained fame for her roles in Ocean’s 8 and Crazy Rich Asians but was originally famous as a rapper. She expressed interest in rap as early as 13 and attended LaGuardia High School of Music & Art and Performing Arts where she learned the trumpet and trained in classical and jazz music. She did not continue her education in music at The State University of New York at Albany where she double-majored in journalism and women’s studies but continued to dabble in tracks and make beats on the side. She continued to make music and rap in her free time when she began working after college, but it wasn’t until her song My Vag was released that Awkwafina gained public recognition as a rapper. As a response to Mickey Avalon’s My Dick, Awkwafina rapped about female genitalia as “a celebration of women”—not as a feminist stance—and to combat the common sexualized narrative of women with comedy with lyrics such as:

My vag squirt aloe vera // Yo vag look like Tony Danza

My vag speak five different language // And told yo vag bitch make me a sandwich

My vag a Beyonce weave // Yo vag a polyester K Mart hairpiece

With this track, Awkwafina gained traction as an Asian American music artist in the male-dominated field of rap at age 24 and got fired by her employers at the time. Small references to her Asian identity were included in her following tracks which continued to use explicit and sexual language with a comedic twist. With these references, Awkwafina presents herself as a confident Asian American woman, successfully combining her Asian and American identities as one rather than separate. In an interview with Daily Beast, she explains that she’s not trying to unite Asians with her music: “It’s about me being Asian and my experience being Asian.”

Not only does Awkwafina challenge the male-dominated music industry as an Asian American rapper but also as an unique female. Ultimately, she’s embracing her identity as something to embrace and boast about in her songs, refusing to see herself as a foreigner physically and verbally. “I want to change the game to make rap that shows I’m not a normal female rapper-it’s now about how rich I am, how much sex I have, or how many boyfriends I have. That’s just not me.”

Awkwafina continues to express herself through her music, but one of particular interest is her collab with Margaret Cho, Green Tea. This song was released in celebration of APAHM and fights against the stereotypes about Asian women, acknowledging the oppressions utilized against Asian women. Dressing in stereotypical outfits that Asians are commonly represented in (hypersexualized Dragon Lady, traditional school uniforms, horror movie dresses), Awkwafina and Cho rap as the “bad” Asians, rebelling against the pure and passive stereotypes of Asian women and taking pride as Asian women in power. By othering themselves even further by not conforming to the conventional Asian female stereotypes, they flip the connotations held with being Asian and a woman to uplift Asians and Asian women.

Listen to her most recent EPIn Fina We Trust! The album is satirical and self-deprecating, including her experiences with racism, plays on machoism, references to her identity as Asian American, and her indifference to men. I suggest Cakewalk and Inner Voices!!

0 notes

Text

asian american indie / r&b / chill elec

A Spotify playlist featuring slow beats and chill vibes with Asian American artists—something to turn on in the background while relaxing.

The following artists featured in the collage above only represent a few of the artists in this 2 hr 20 min playlist: RINI, Yuna, Sophia Black, MISO, Giraffage, khai dreams, and Jhene Aiko.

0 notes

Text

BTS Phenomenon: Good or Bad?

BTS is a 7-member Korean boy band that has recently peaked the interest of Western audiences. Starting as an old-school hip hop group in 2012, this group has evolved into a mainstream pop idol group that plays with different styles to accommodate to each of its members strengths and preferred styles. With a variety of talent, this group has captured the hearts of millions as seen with their 14.9 million Twitter followers and world-wide sold out concerts. Also, their global success has broken many records: first Korean act to debut at no. 1 on Billboard’s top 200 (twice), first K-pop act to be nominated and awarded with a Billboard Music Award, most viewed YouTube video in 24 hours, and several more. Their triumphs in the music industry are noteworthy, and their recent recognition by Western countries can only attest to their musical and dancing abilities.

Their success also proves that Asians can flourish in the music industry, but if a South Korean pop group can be this successful in North America, why don’t we see more successful Asian Americans in the music industry?

While BTS’s fame has been upheld as this beacon for Asian representation in the music industry, does the group’s fame also limit Asian American musical artists? Is the popularization of BTS, and essentially K-pop, creating a narrative for what “Asian music” should and can be?

If we believe that BTS is the long-awaited Asian representation to be seen in the American music industry, we’re failing to recognize recent Asian American artists, such as Bruno Mars, Jhené Aiko, Far East Movement, and others. By valuing this K-pop group over Asian American artists, we’re valuing the foreign over the domestic, as well as, defining what Asian music artists should look like.

The difference here is that K-pop embodies its foreignness, clearly seen with its name for the genre, Korean-pop, as well as its use of mostly Korean in its songs. Advertised as foreigners, BTS sees an abundance of praise and respect for breaking boundaries and gaining the love of millions despite a language barrier not really because the leader speaks English. Asian American artists are no strangers to a foreigner status; they’ve lived as perpetual foreigners for as long as they’ve lived in America. Despite the American birth certificate, the “American” accent, or love for American food, Asian Americans have yet to be properly accepted as Americans.

Suddenly, Asian music has been restricted to those that speak their respective language and are (usually) of East Asian descent. If we continue to embrace the foreign as sole representation for Asian music, we’ll be completely ruining the chances for emerging Asian American artists who won’t be able to fit the necessary requirements to be recognized as an Asian artist.

Now, should BTS be targeted as a guilty party for further encouraging the outsider status of Asian Americans?

First and foremost, there is a chance that this group is not even privy to this problem because they come from a racially homogenized country. In South Korea, they’re part of the majority, not the minority; with this in mind, they may not be as fine tuned towards the convoluted White patriarchy and its actions towards minorities. In addition to this, they’re usually only recognized as the heroes of South Korea. Due to their fame, this group is a prized possession of the country for their fame overseas. Just the mention of “BTS” is enough to surge some sort of pride in older Korean citizens’ hearts because of the new found respect and attention being received by the small country. The group’s fame is enough to incite attention from the South Korean President via an album release. With this kind of constant attention and respect from 51 million people, it’s possible that they don’t really see their fame as a bad thing.

The lack of awareness, however, over this issue doesn’t erase the effects of their fame. Still, it doesn’t mean that they’re exactly at fault for the popularization of their own music. This puts the Asian Americans in an awkward situation in which they’re excluded from the music industry and are left to support a group that (may unintentionally) further promotes their exclusion from the music industry.

0 notes

Text

Classism with Crazy Rich Asians

One of the biggest hits of 2018, Crazy Rich Asians was not the easiest movie to make. However, it proved that Hollywood and its audiences are invested in more diverse stories. It tells the story of Rachel Chu who travels to Singapore to meet her boyfriend, Nick’s extended family and coming to terms with his immense wealth and the clientele it attracts.

In early stages of production, a producer suggested the character of Rachel Chu be played a white actress. While that idea was ultimately scrapped, it was not the only issue amidst conception. Netflix initially offered the filmmakers a release deal, but it was ultimately decided that the movie would be released with Warner Brothers, which would guarantee the film would reach a wider audience and ultimately led to its widespread success.

youtube

“Crazy Rich Asians” was the first mainstream film in 25 years to feature an all asian cast, following in the footsteps of the 1993 adaptation of Amy Tan’s “The Joy Luck Club.” The lives of different Asian and Asian Americans are explored, yet problems arise within the setting of the film. Rachel’s upbringing as the daughter of a single immigrant mother immediately singles her out from the aristocratic lifestyles of Nick’s family. This leads to discussions about who is and is not acceptable to invite into the Young’s world and the prejudice that plagues Asian communities around the world.

As groundbreaking as the film is, the majority of it is focused on this 1% group of Asia’s foremost millionaires. Greed and pride get in the way of the storyline, and most of the characters are asked to reevaluate what it means to be a successful individual of Asian descent, and figures out ways in which it can help or harm your personal life. Some critics felt that it glorified the extravagant lifestyles of these individuals and did not accurately represent the multiple backgrounds of East Asians that could be represented on the big screen.

“Crazy Rich Asians” provided a platform for us to discuss the classism that plagues Asian community and highlighted the complex lives of the Chu and Young families. It also highlighted the double standard that is played against the children of immigrants and those individuals that were born and raised in Asia.

Source: SEEING IS BELIEVING: WHAT THE RISE OF CRAZY RICH ASIANS SIGNALS FOR THE FUTURE OF HOLLYWOOD. By: HO, KAREN K., Time International (South Pacific Edition), 08180628, 8/27/2018, Vol. 192, Issue 8

0 notes