Text

The urns were likely constructed approximately 2800-1000 years ago. During this time, burial urns were a common form of interment in coastal areas, in caves, and on hilly terrain. Earthenware jar burials are more common across the Philippines, but the limestone urns are mostly found in Cotabato. Burial urns like these are typically used for secondary burials, which means the jars are not the first vessel for the deceased, but rather an individual’s final resting place after they are first laid to rest.

The urns each had matching covers at their time of use, but natural disasters like earthquakes and even human disturbance over the years moved and damaged some pieces. The urns are either squared or rounded with geometric lining, a foot or more in height, and quite heavy. The covers or lids feature anthropomorphic, human-like bodies protruding from the center. Some have limbs that extend out to the edges of the cover. Several covers have geomorphic lines and patterns that match the urns. Faces are highly individualized, carved with distinct facial features, including ears, earring holes, noses, smiles, frowns, and other expressions. It is hypothesized that the figures on the urns were meant to identify the deceased. The urns were noted to have human remains inside them when they were first acquired in the 1970s, although now their location is mostly unknown.

Research in Maguindanao, the province of Cotabato, only began in the 1960s, but archaeologists have reported many anthropomorphic vessels from this region. Several urns recovered were buried along with other smaller jars that carried personal adornments such as shell and ceramic bracelets and iron plates.

… At the conclusion of this exhibit, it will be reevaluated where this collection will go and how it will best serve the involved communities. These artifacts will likely be repatriated–returned back to the Philippines–and placed first under the care of the National Museum of the Philippines in Manila. As a cultural agency of the Philippine heritage the National Museum serves as a repository of archaeological materials. Although there are limestone urns elsewhere among private museums in the Philippines and the U.S., repatriation of these artifacts back to the Philippines is the first step to invite the Manobo back to the conversation to determine who will be the next stewards of these cultural materials. Closer to home, the future location of the collection in the Philippines reinforces the community’s place over how the artifacts are managed, exhibited, and shared.

0 notes

Text

The big questions archaeologists want to answer also shape the value of their finds. They want to fill in the missing pieces of human history, and sometimes the newer pieces help complete the puzzle. Protecting and studying our entire past, not just the oldest parts, helps us get a full picture of how humans have lived and changed through time. So, in archaeology, it’s not just about discovering the oldest artifacts; it’s about uncovering and understanding the fullness of human history.

As an example, research in Ifugao confronts the prevailing notion that the antiquity of a site is its most defining feature. Previous studies have proposed that the terraces were to be at least 2,000 years old. However, Acabado and Martin’s studies suggest a more recent origin, around 1600 CE, coinciding with Spanish colonization. This new date does not remove the terraces’ significance but rather refocuses their historical narrative.

The terraces are not relics of the past; they are a testament to the Ifugao’s resilience and ingenuity. The revised dating indicates the Ifugao’s remarkable response to colonial incursion, a physical manifestation of cultural identity and resistance. Understanding these terraces as a relatively recent innovation underscores their role in Ifugao society’s adaptive strategies to external pressures.

This perspective challenges deep-seated assumptions about the value of ancientness in archaeological sites. It emphasizes the historical events that shaped the terraces and the community that created and maintained them. In doing so, it connects the past to the present, ensuring the terraces’ continued relevance to the Ifugao people’s living culture and their ongoing story of resistance, adaptation, and survival.

… Thus, the concept of prehistory, which implies a disconnection from the present, undermines Indigenous and local histories. Current research in Ifugao demonstrates a continuous historical thread that is woven into the fabric of Ifugao society. This continuity is manifested in the enduring rice cultivation practices and rituals that have been passed down through generations.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

In Anda, Bohol, Lamanok Point is home to significant prehistoric evidence including hematite rock paintings and burial sites, revealing aspects of early civilization dating back tens of thousands of years. The rock art authenticated by the National Museum of the Philippines, served as ancient community gathering markers. Additional findings at this site include wooden coffins, human skeletons, and jar shards, further illuminating the life of early inhabitants. In 2020, this area was designated as an “Important Cultural Property.”

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The article boldly connects Austronesian migration to events just a thousand years in the past, potentially compressing a complex history of five millennia into a too-concise summary. The reliance on linguistic and genetic evidence might not fully capture the complex dynamics of human migration, often overlooking the contributions of pre-existing populations and simplifying migration patterns as linear and unidirectional.

The article does make an important point about how genetic research can inform our understanding of the past. Yet, it’s important to remember that even DNA has its storytelling limits. These genetic narratives, like any other, can be colored by the lenses through which we look at them – either from dominant politics or the unintentional shade of a researcher’s own perspective.

A stark reminder of the power such interpretations hold comes from Jean-Paul Demoule’s “The Indo-Europeans,” which recounts a grim chapter where the misuse of such theories underpinned the horrors of Nazi ideology.

Therefore, it’s not just important but essential for researchers to examine their methods with a critical eye and invite cross-disciplinary checks. This ensures their findings don’t just stand up to scrutiny but mirror the complexities of history. After all, history is rarely a straight line – it’s more of a dance, with steps backward, forward, and often, in a completely unexpected direction.

Compounding this issue is the scarcity of systematic excavations across the Philippines. With over 7,000 islands comprising our nation’s geography, conducting thorough archaeological explorations becomes a Herculean task, both logistically and financially. As a result, large swathes of our history remain untouched and unexplored.

Furthermore, there’s a tendency to favor grand historical narratives over the smaller, everyday discoveries that offer invaluable insights into past societies. This preference often stems from nationalist agendas, promoting a sanitized view of history that overlooks the nuances and complexities of our shared past. By neglecting these smaller finds, we risk distorting our understanding of the past and perpetuating narrow interpretations that fail to capture the full spectrum of human experience.

Take, for instance, the controversy surrounding the elusive Kalaga Putuan Crescent (KPC) – a purported kingdom located in what we now know as Butuan in Agusan del Norte. The mere mention of this kingdom has the potential to rewrite the narrative of pre-colonial Philippine history. A recent study delves into the depths of this “lost kingdom,” intertwining genetic and archaeological evidence in an impressive attempt to unveil the mysteries of precolonial Philippine culture.

This publication projects optimism, advocating for the power of scientific archaeology in the Philippines. Yet, amid the excitement, there’s a shadow of controversy, which highlights the need for more stringent, ethical research practices in archaeology to ensure our cultural artifacts are not misused or misrepresented.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Compounding this issue is the scarcity of systematic excavations across the Philippines. With over 7,000 islands comprising our nation’s geography, conducting thorough archaeological explorations becomes a Herculean task, both logistically and financially. As a result, large swathes of our history remain untouched and unexplored.

Furthermore, there’s a tendency to favor grand historical narratives over the smaller, everyday discoveries that offer invaluable insights into past societies. This preference often stems from nationalist agendas, promoting a sanitized view of history that overlooks the nuances and complexities of our shared past. By neglecting these smaller finds, we risk distorting our understanding of the past and perpetuating narrow interpretations that fail to capture the full spectrum of human experience.

Take, for instance, the controversy surrounding the elusive Kalaga Putuan Crescent (KPC) – a purported kingdom located in what we now know as Butuan in Agusan del Norte. The mere mention of this kingdom has the potential to rewrite the narrative of pre-colonial Philippine history. A recent study delves into the depths of this “lost kingdom,” intertwining genetic and archaeological evidence in an impressive attempt to unveil the mysteries of precolonial Philippine culture.

This publication projects optimism, advocating for the power of scientific archaeology in the Philippines. Yet, amid the excitement, there’s a shadow of controversy, which highlights the need for more stringent, ethical research practices in archaeology to ensure our cultural artifacts are not misused or misrepresented.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

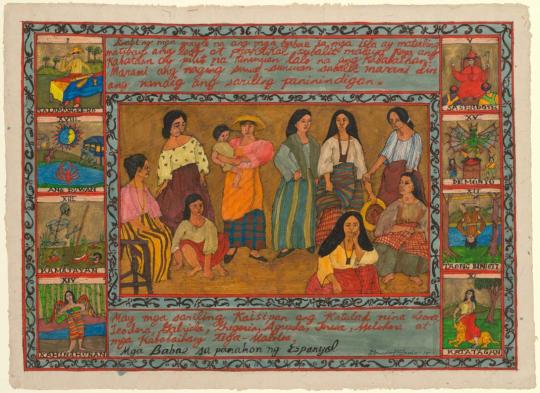

Brenda Fajardo (B. 1940, Manila, the Philippines) - Mga Babae sa Panahon ng Espanyol (Women during the Spanish colonial period) from 'Cards of life - Women's series,' 1993.

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

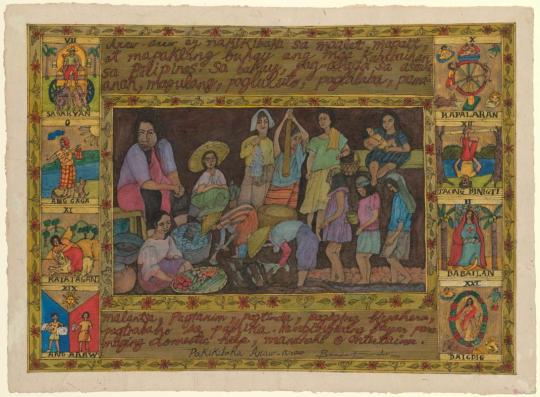

Brenda Fajardo (B. 1940, Manila, the Philippines) - Pakikibaka Araw-araw (Daily struggle), from 'Cards of life - Women's series' 1993.

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

MANILA — A month after his abduction, surfaced environment defender Francisco “Eco” Dangla III detailed his harrowing experience at the Commission on Human Rights, on April 26.

Dangla and fellow activist Axielle “Jak” Tiong were mauled into a van by armed men on March 24 in barangay Polo, San Carlos, Pangasinan. Later on, the two activists would be found on March 28, after more than 600 individuals and international and local organizations campaigned for their immediate release.

Their abductors are still at large, prompting the activists to seek sanctuary.

Dangla believes that their abductors are state agents, due to the build up of harassment incidents prior to the abduction.

In fact, Dangla had been tagged as a “terrorist” and “threat” by State forces. This is according to the 2019 presentation of the Regional Peace and Order Council of Region 1.

“Since 2014, I have been a victim of several forms of harassment, intimidation, vilification, and threat in different chapters of my service to the people and the environment,” he said in Filipino.

The harrowing ordeal

Dangla said that on the day of the abduction, the unidentified men pointed their guns at them, pushing them to submission.

“When we arrived at a place, which looked like a safe house, they said that our lives were at their hands. We cannot do anything. They threatened to kill us,” Eco recalled.

He also added that the abductors threatened to burn and bulldoze them. “They released a cobra. We also heard a sound similar to the bulldozer. They said that they would burn us, that they would put us under the wheels of the bulldozer. Later on, I would smell burning plastic and wheels,” Eco said in Filipino.

There were moments when both Dangla and Tiong felt hopeless in the three days of distress. Dangla said, “I told myself, maybe it’s time. Maybe they would kill us now. But until the end, I still tried to explain our environmental initiatives, until they got angry at us.”

“They tried to give us an ultimatum. They do not want to hear our explanation about the environment. Instead, they asked us about people, about names we do not know, because they wanted to connect us to CPP-NPA,” he said.

It also came to the point that the abductors also threatened their families. “We experienced an unimaginable intimidation and threat to my life through physical and psychological torture. Worse, they threatened the lives of our loved ones, and my family,” he said.

Dangla said that prior to their abduction, he and Tiong suffered from multiple cases of red-tagging and harassment, stemming from their advocacy work. They are both convenors of the Pangasinan People’s Strike for Environment (PPSE), a local grassroots network of environmental advocates.

Overwhelming support and solidarity

The environment activists were released before the sunrise of March 28. They were blindfolded prior to their release so they were not able to identify the trail of place. Dangla even thought that the abductors would dispose of them during that time.

“When we were surfaced, I saw the overwhelming support of environment groups, churches, and individuals. From there, I felt that despite the strength of our enemy, if we fight in unison, we can achieve victories,” Dangla said.

He expressed his deepest gratitude to all the organizations and individuals who campaigned for their release. Barangay Polo residents also provided support to their parents.

“Without the quick response and campaign of various groups and sectors, including the church in the national and international scope, maybe our abductors would not release us,” he said.

Speaking at the same press conference, Jonila Castro, another surfaced environmental activist who has been fighting against the reclamation projects in Manila Bay, expressed support.to Dangla.

Castro and her fellow activist Jhed Tamano, were abducted on September 4, 2023. Weeks later, they were presented as fake surrenderees by the NTF-ELCAC, only for the two activists to expose the violence they suffered.

She also highlighted that instead of committing or being oblivious to the rampant human rights violations, the government should address the problems caused by climate change such as El Niño.

Castro is now the advocacy officer for water and reclamation of the Kalikasan People’s Network for Environment (PNE). She echoed Dangla’s sentiments that the abductions are used to silence environmental defenders and activists opposing destructive projects.

“These abductions are part of a larger pattern of natural resource plunder by foreign corporations, often with government and military support. Activists opposing these projects and defending local community rights are viewed as obstacles to profit-making and are therefore the target for intimidation, harassment, and violence,” she said.

Continuing the fight against destructive environmental projects

As convenors of the PPSE, Dangla said that they are at the forefront of opposing destructive mining projects.

Among these projects is the 10,000 hectares of black sand off-shore mining in the Lingayen Gulf. This will cover the towns of Sual, Labrador, Lingayen, Binmaley, and Dagupan, which seek to extract 25 million of magnetite sand yearly for 25 years.

According the government data from the Bureau of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources (BFAR), around 28,000 fisherfolk are dependent on the gulf for their livelihood. The project could also affect the biodiversity and ecosystems in the area, according to a BFAR aquaculturist.

In addition to this, Executive Order 130 (EO 130) by former President Rodrigo Duterte, which sought to lift the moratorium on mineral agreements, prompt the surge of applications.

“Around 84,000 hectares of lands are at stake due to the Executive Order,” Dangla said.

They are also opposing the plan of the local government to build six nuclear power plants. In 2023, PPSE reported that the LGU is encouraging community members to sign a statement of community acceptance for the projects.

Despite the harrowing violence that they experienced, Dangla vows to continue the fight. “My plan is to continue and maybe we will still plan how we move seamlessly, but my will is firm to continue the fight.”

According to the human rights group Karapatan Central Luzon, the number of surfaced activists is five (5), but there 14 defenders still missing. Three of them are from Central Luzon: Steve Abua, Diodicto Minzo, and Joey Torres.

full article: https://www.bulatlat.com/2024/04/26/despite-suffering-torture-environmental-defenders-continue-fight-against-destructive-projects/

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

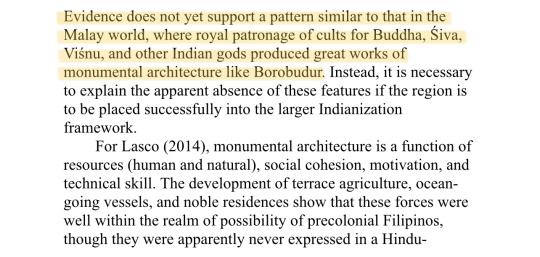

Why the Philippines does not have Hindu-Buddhist temples like other places in Southeast Asia such as Borobudur and Angkor Wat, according to “The Problem of the Visayas in Southeast Asian History and Historiography” by David Gowey

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Towards the end of the 19th century, there were only 18 licensed physicians in the Visayas, 2 in Mindanao, and 42 in Luzon.

The babaylanes remained integral to Visayan society for their needed healing activities, a fact that even priests acknowledged since most of them only had little training in the natural sciences (and were unfamiliar with local flora).

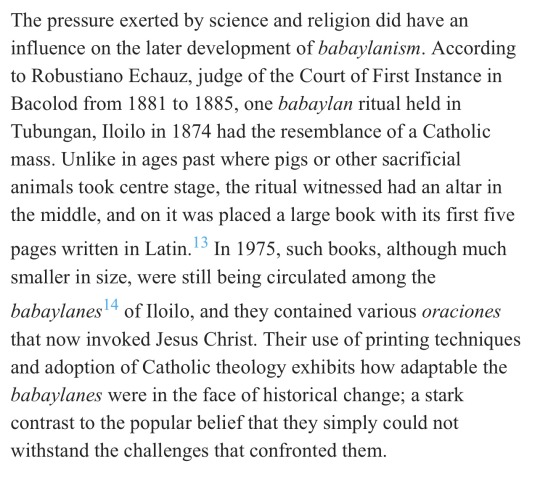

Their use of printing techniques and adoption of Catholic theology exhibits how adaptable the babaylanes were in the face of historical change; a stark contrast to the popular belief that they simply could not withstand the challenges that confronted them.

It was only up in the mountains where they could conduct their rituals, prayers, and collect herbs in peace, away from the busy developments of nascent urban communities.

Their prestige as healers offered the babaylanes relative ease to move in and out of society, and this would later be instrumental in the two babaylan-led uprisings in Negros.

Excerpt from “The Babaylan Survived Colonialism” (2021) by Pippo Carmona

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

me 🙋♀️🙋🙋♂️

who wants a list of folk catholic ritual incantations used by tindal dusuns

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fundraising effort for Palestinian and Fil-Palestinian families who arrived in the Philippines. See Twitter link below for thread updates:

https://twitter.com/lizzyfaith/status/1772506113591607612

589 notes

·

View notes

Text

when you get so nostalgic for the past that you start romanticizing people you never even had a connection with

1 note

·

View note

Text

filipinos have a tendency to call non-hispanicized ethnic groups tribes, be it their own precolonial ancestors or contemporary groups. 1500s visayans are tribal in the same way 2020s tausug and mansaka people are tribal. only those from christianized/hispanicized ethnic groups (tagalogs, cebuanos, ilocanos, kapampangans, etc) do away with the word tribe.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

two decades alive on this earth and i still can’t tell my veteran tisoy actors apart. examples: jaime fabregas, ron valdez, eddie garcia, papa ni andi eigenmann.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Precolonial Visayan-inspired prenup photoshoot, September 2022. Photographs by The Bamboo Studios, makeup by Harvy Christian Baliguat, hair by Brena May, costume from Sharrie Villaver, and accessories and assistance by Minxie Villaver. Location of shooting is Payag Coffee House in Busay, Cebu.

4 notes

·

View notes