Text

started playing Yaku Tsuu - Noroi no Game

a cursed visual novel

236 notes

·

View notes

Text

"In February, four months after Hamas broke through the fence around the Gaza Strip, Israel’s military establishment secretly employed hundreds of Palestinian workers from the West Bank to repair it. The incident represented one of the only times that Palestinian workers have been allowed to return to work within the Green Line after the Israeli government revoked almost all of their work permits in October.

The Israeli military establishment’s decision to rehire previously-banned Palestinian workers, which bypassed elected lawmakers on the official Security Cabinet, represents a growing tension between Israeli leaders’ divergent approaches to Palestinian laborers.

(...)

In the post-October 7th moment, Israeli leaders are retracing this familiar debate about Palestinian labor, but the rise of the far right has meant that the exclusion pole is much more powerful than in previous iterations. According to Hussain, a 60-year-old Palestinian laborer and West Bank resident who worked in construction near Tel Aviv before October 7th, Israel’s cancellation of almost all work permits has created one of the most dire crises Palestinian workers have ever faced. “The situation was never this bad even during the First or Second Intifada,” Hussain told Jewish Currents, asking that only his first name be used to protect his job prospects. “I have a family of seven and I haven’t worked in five months. I haven’t been able to buy meat since October 7th. We are relying on Allah and no one else.”

(...)

In the first two decades after it occupied the West Bank and Gaza Strip in 1967, Israel opted to integrate a Palestinian labor force in the hopes that ensuring a basic level of welfare for Palestinians would maintain calm. But Israel changed tack with the onset of the First Intifada, the late 1980s Palestinian uprising against the occupation. In that period, Israel’s repeated closures of the West Bank and Gaza Strip, which intensified following a wave of Palestinian militant attacks, barred tens of thousands of Palestinians from reaching their workplaces. This created a crisis for employers in the construction sector, where the dependency on Palestinians was most acute, and since Israeli workers were unwilling to work in these hazardous jobs—which also became socially stigmatized due their association with Palestinians—the government had no option left but to bring in workers from elsewhere. As a result, by 1996, the Israeli government had granted 106,000 permits for foreign migrant workers.

The shift to supposedly pliant and depoliticized foreign labor was seen as not only a way to keep the Israeli economy going, but also a strategy to quash the Intifada, which leveraged Israel’s dependency on Palestinian workers to put forward political demands through frequent strikes. “When the working Palestinian population rose up and threatened the interests of the state and employers, migrant workers were brought in as a sort of strike-breaker population,” said activist and anthropologist Matan Kaminer, who researches migrant workers in Israel. Bringing in a non-Palestinian labor force was also seen as preparation for an imminent two-state agreement: “The Oslo years also represented the most significant attempt to wean Israel off Palestinian labor because the government genuinely believed that there would be political separation,” Preminger said.

For right-wing Israelis, however, the potential replacement of Palestinian labor with foreigners triggered other latent anxieties. “The Israeli right was worried about foreign workers because if they were given rights and equality as non-Jews, it could create a liberal society where the first and most important marker is not the fact that you’re Jewish,” said Yael Berda, an academic who studies Israel’s permit regime. Preminger echoed this point: “In Israel, there is a constant negotiation between the inclusionary economic pressure to hire cheap or otherwise exploitable labor, and the exclusionary political pressure of an ethnonationalism that doesn’t want any non-Jews.” To manage this tension, Israel restricted the rights of its new migrant labor force. Even as more than 100,000 foreign workers were brought to Israel by the turn of the millennium, they were not allowed to bring their families. Most came on five-year visas, which gave a clear terminus to their lives in Israel, and there was no route to naturalization. Guaranteeing that migrants’ time in Israel would be finite “ensured that the costs of social reproduction—care of children and the elderly, long-term medical treatment, and so on—were not borne by Israeli society,” Kaminer said, adding that “all these draconian measures were designed very explicitly to ensure that migrant workers don’t become a permanent non-Jewish population.”

Despite these measures, Israeli leaders remained concerned that this population would naturalize, a problem they didn’t have with Palestinian workers. “One of the main advantages [of Palestinian labor] is that Palestinians are part of the economy without being part of the polity, which means you can extract labor without paying the social and political cost of their belonging. At the end of the day, they return to their homes,” said Berda. These concerns, alongside the economic and security benefits Israel enjoyed by hiring subordinated Palestinian workers, eventually led to their return.

For their part, Israeli employers welcomed this shift because, in Preminger’s words, “Palestinians were familiar with the land and the language, and they knew how to do the work, and how to work with Israelis.” Israel also benefited in other ways: As opposed to foreign workers, who send remittances back to their home countries, “Palestinian workers live in a captive market, and all their money ultimately ends up getting recycled into the Israeli economy,” said Abed Dari, a field coordinator with the workers’ rights NGO Kav LaOved. Leila Farsakh, a Palestinian political economist, explained that Israel’s decision to employ Palestinians further consolidated the de-development of the occupied territories, with labor migration to Israel—which accounted for up to one third of the Palestinian workforce during the ’90s—decimating smaller industries in the West Bank and the Gaza Strip. The higher salaries Palestinian workers were offered in Israel also contributed to pulling them out of agricultural work, facilitating Israel’s land confiscations. “Palestinian labor migration has played a key role in binding and subordinating the Palestinian economy to Israel,” Farsakh explained.

Even more crucially, labor migration became a central pillar in Israel’s regime of control over Palestinians, especially once Israel established its extensive system of work permits in the 1990s and set up a network of checkpoints with which to surveil Palestinian labor after the Second Intifada broke out in 2000. As Berda argued in her book, Living Emergency: Israel’s Permit Regime in the Occupied West Bank, the permit regime constitutes “one of the most highly developed systems of control over a civilian population anywhere in the world.” Since a permit can be denied or revoked if the applicant is found to have engaged in any political activity—even peaceful protest—the system has served as a successful deterrent against individual Palestinians’ political participation. The broader closure policy in response to Palestinian uprisings also offered a collective deterrent, what Berda termed “an instrument for managing the political conflict in the labor market.” Following the Second Intifada, Israel also expanded the category of “security threat,” which led the number of Palestinians blacklisted from receiving movement permits to grow from only a few thousand before the Second Intifada to one-fifth of the male Palestinian population by 2007. Those who were denied permits sometimes became Israeli collaborators, which caused widespread suspicion and frayed social bonds within the occupied West Bank—as did the emergence of a class of Palestinian brokers invested in facilitating and managing Israel’s labor regime. These dynamics have continued into the present: As Farsakh noted, “the fact that the West Bank didn’t explode after October 7th is a testament to the success of this pacification policy.”

(...)

In this context, far-right politicians’ hardline rhetoric against Palestinians, and their insistence on bringing in foreign labor, seem likely to result not in a replacement of Palestinian workers but in “a new security regime for managing them,” according to Farsakh. Berda concurred, adding that “the influx of migrant workers will give Israel even more leverage over Palestinian workers, which will mean worse working conditions and more surveillance.” Indeed, the military establishment’s recently proposed pilot for a partial reentry of Palestinian workers explicitly suggests the use of “advanced monitoring systems that have never been used before” as a way to address the far right’s concerns about Palestinian militancy. In crafting this harsher version of the previous system, Israel looks poised to draw from the precedent of both the Intifadas, bringing in a migrant labor population to depress Palestinians’ power as it did in the ’90s while also heightening surveillance on Palestinian workers as in the 2000s. For the Palestinian workers on their receiving end, these emergent re-entry policies constitute a bitter lifeline, offering a short-term improvement on months of unemployment, but a long-term erosion of their already precarious rights."

50 notes

·

View notes

Text

'The Lady Ghost' by Adelaide Claxton

(1841 - 1927)

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

The Kent State massacre has been in our collective consciousness lately so here's my contribution to that.

57 notes

·

View notes

Text

never get tired of the colors house centipede juveniles turn in death

632 notes

·

View notes

Text

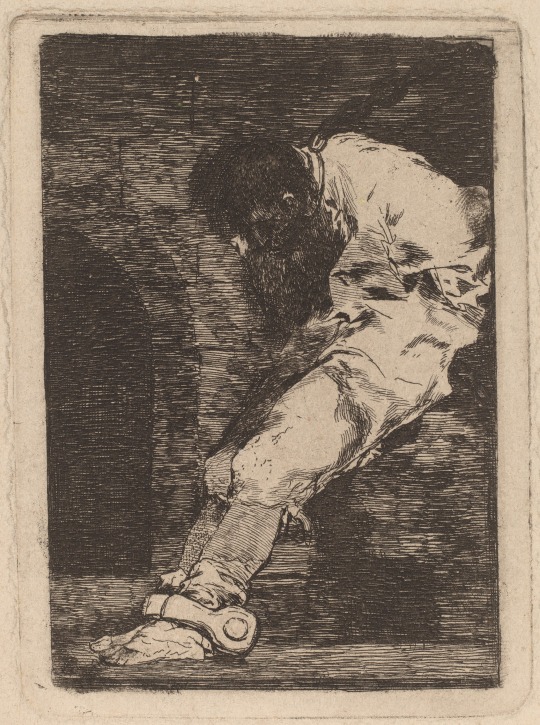

"IF HE IS GUILTY, LET HIM DIE QUICKLY"

FRANCISCO DE GOYA // circa 1810

[etching | U/D]

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

picturing a roman empire equivalent of reactionaries who say "if you don't like it here then move somewhere else"

33K notes

·

View notes

Text

"Capitalists – unlike lords – had to worry about competition from one another."

like i know it's about like market competition but it's quite funny when feodal lords went to war with each others

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Austin Powers makes so much more sense now that I've watched more of Peter Wyngarde as Jason King.

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mice, Radish, and Carrot

1926

Color woodblock print

Takahashi Hiroaki (Shotei)

Japanese, 1871–1945

Art Institute Chicago

2K notes

·

View notes

Photo

Source: Yokohama Kaidashi Kiko Book of Paintings Art Book

by Hitoshi Ashinano

223 notes

·

View notes

Text

"I have studied the Portuguese revolution for 20 years. Looking at the photos from the time, across all sectors, it’s very difficult to find someone who is not smiling. This brings us to the sense that in a revolution we reconcile with work again. In place of alienated work, we reconcile with ourselves. People were struggling and working as never before in their lives. They belonged to their work. They were deciding what to do and they were doing what they decided. Things changed completely. Portugal had been probably one of the saddest countries in Europe. People wore black. There had been three hundred years of Inquisition and 48 years of dictatorship. And now people were just smiling. This takes us back to the ontology of social being of Gyorgy Lukacs and to the work of two incredible socialists, Rosa Luxembourg and Simone Weil. They remind us that we can recover our happiness, pleasure, sense of humanity; we can do it in the process of struggle.

(...)

The revolution is remembered very differently depending on who you are. For most of the workers in schools, in hospitals, in public services, in factories, and in local communities the 25th of April is the most celebrated day in all Portugal. People sing Grandola Vila Morena, the song of the Carnation Revolution. They don’t sing the national anthem! Within the state itself, the social democrats want to celebrate the end of dictatorship and the coup d’état, but they don’t want to celebrate the dual power in the revolution. They consider it a process of chaos and craziness to which the representatives of democracy brought stability and common sense. The right wing like the Liberal Initiative say more or less the same as the social democrats, that the country was okay after the coup in 1975 that ended the sovietisation of the armed forces. The fascists say that after the 25th of April everything was bad in Portugal. If we talk about the public use of memory, there is a huge monument, a sign to Africa, a totally neofascist monument inaugurated 30 years ago but there is not one single monument to the liberation movements or to Amilcar Cabral, or to the forced labourers. Otelo Carvalho is not considered a national figure, but the right-wing generals were recently honoured by the president of the republic.

They are trying to vanish the memory of the revolution because it was the biggest nightmare of the Portuguese state. They really were afraid. And they really lost. For you to have a notion, 18% of the national wealth was transferred from capital to labour during 1974 to 1975. It was the biggest moment in Portuguese history."

Remembering the Portuguese Revolution

On 25 April 1974 the junior officers of the Armed Forces Movement (MFA) released a radio communique: ‘The Portuguese armed forces appeal to residents of the city of Lisbon to remain in their homes and remain in the utmost calm.’ But the workers of Lisbon didn’t stay at home. This was day one of the Portuguese revolution.Raquel Varela, author of A People’s History of the Portuguese Revolution,…

View On WordPress

14 notes

·

View notes