Text

References

Abramovich, A. (2016). Preventing, reducing and ending LGBTQ2S youth homelessness: The need for targeted strategies. Social Inclusion, 4(4), 86-96. https://doi.org/10.17645/si.v4i4.669.

Ancil, G. S. (2018). Canada, the perpetrator: The legacy of systematic violence and the contemporary crisis of missing and murdered indigenous women and girls. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, 2018.

Assembly of First Nations (AFN). (2013). Fact Sheet - First Nations Housing on Reserve. https://www.afn.ca/uploads/files/housing/factsheet-housing.pdf.

Bingham, B., Moniruzzaman, A., Patterson, M., Sareen, J., Distasio, J., O'Neil, J., & Somers, J. M. (2019). Gender differences among indigenous canadians experiencing homelessness and mental illness. BMC Psychology, 7(1), 57-57. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-019-0331-y.

Brandon, J., Peters, E. J., & Manitoba Research Alliance. (2014). Moving to the city: housing and Aboriginal migration to Winnipeg. CCPA (Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives). https://policyalternatives.ca/sites/default/files/uploads/publications/Manitoba%20Office/2014/12/Aboriginal_Migration.pdf.

Bretherton, J. (2017). Reconsidering Gender in Homelesness. European Journal of Homelessness, 11(1), 1-21. https://www.feantsaresearch.org/download/feantsa-ejh-11-1_a1-v045913941269604492255.pdf.

Burns, V. F., Sussman, T., & Bourgeois-Guérin, V. (2018). Later-life homelessness as disenfranchised grief. Canadian Journal on Aging, 37(2), 171-184. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0714980818000090.

Clifford, B., Wilson, A., & Harris, P. (2019). Homelessness, health and the policy process: A literature review. Health policy (Amsterdam, Netherlands), 123(11), 1125–1132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthpol.2019.08.011.

Dyck, L. E., & Patterson, D. G. (2015). On-reserve Housing and Infrastructure: Recommendations for Change, Standing Senate Committee on Aboriginal Peoples. Standing Senate Committee on Aboriginal Peoples. https://sencanada.ca/content/sen/Committee/412/appa/rep/rep12jun15-e.pdf.

Kauppi, C., Pallard, H., & Stephen, G. (2013). Societal constraints, systemic disadvantages, and homelessness. An individual case study, 11(7), 8.

Levine-Rasky, C. (2011). Intersectionality theory applied to whiteness and middle-classness. Social Identities, 17(2), 239-253. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504630.2011.558377.

MacTaggart, S. L. (2015). Lessons from history: The recent applicability of matrimonial property and human rights legislation on reserve lands in canada. The University of Western Ontario Journal of Legal Studies, 6(2).

Mashford-Pringle, A., Skura, C., Stutz, S., & Yohathasan, T. (2021). What we heard: Indigenous Peoples and COVID-19. Public Health Agency of Canada. https://www.canada.ca/content/dam/phac-aspc/documents/corporate/publications/chief-public-health-officer-reports-state-public-health-canada/from-risk-resilience-equity-approach-covid-19/indigenous-peoples-covid-19-report/cpho-wwh-report-en.pdf.

Milaney, K., Tremblay, R., Bristowe, S., & Ramage, K. (2020). Welcome to canada: Why are family emergency shelters ‘Home’ for recent newcomers? Societies, 10(2), 37. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc10020037.

Nishnawbe Aski Nation & Together Design Lab (NANTDL). (2018). Nishnawbe Aski Nation response to the First Nations National Housing and Infrastructure Strategy. Nishnawbe Aski Nation. http://www.nan.on.ca/upload/documents/nan-housing_position_paper-final.pdf.

O’Donnell, V., Wallace, S. (2011). First Nations, Métis and Inuit Women. Component of Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 89-503-X. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/en/pub/89-503-x/2010001/article/11442-eng.pdf?st=1wx3UPy6.

Palmater, P. (2020). Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Indigenous Women and Girls in Canada. Canadian Feminist Alliance for International Action. https://pampalmater.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/P.-Palmater-FAFIA-Submission-COVID19-Impacts-on-Indigenous-Women-and-Girls-in-Canada-June-19-2020-final.pdf.

Robson, R. (2008). Suffering An Excessive Burden: Housing as a Health Determinant in the First Nations Community of Northwestern Ontario. The Canadian Journal of Native Studies, 28(1), 71-87. http://ezproxy.lib.ryerson.ca/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/suffering-excessive-burden-housing-as-health/docview/218084458/se-2.

Schwan, K., Versteegh, A., Perri, M., Caplan, R., Baig, K., Dej, E., Jenkinson, J., Brais, H., Eiboff, F., & PahlevanChaleshtari, T. (2020). The State of Women’s Housing Need & Homelessness in Canada: A Literature Review. Hache, A., Nelson, A., Kratochvil, E., & Malenfant, J. (Eds). Toronto, ON: Canadian Observatory on Homelessness Press.

Statistics Canada. (2017, October 25). The housing conditions of Aboriginal people in Canada. https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2016/as-sa/98-200-x/2016021/98-200-x2016021-eng.cfm.

Waegemakers Schiff, J., Schiff, R., & Turner, A. (2016). Rural homelessness in western canada: Lessons learned from diverse communities. Social Inclusion, 4(4), 73-85. https://doi.org/10.17645/si.v4i4.633.

Yakubovich, A. R., & Maki, K. (2022). Preventing gender-based homelessness in canada duringthe COVID-19 pandemic and beyond: The need to account for violence against women. Violence Against Women, 28(10), 2587-2599. https://doi.org/10.1177/10778012211034202.

0 notes

Text

What Must be Done to Effectively Combat and Support Indigenous Women’s Homelessness?

It takes solutions that address numerous and overlapping problems for Indigenous communities to meet the multifaceted needs of Indigenous women who have experienced or are at risk of experiencing homelessness.

Around 2017, a Canadian National Housing Strategy was established, emphasizing Housing First initiatives for long-term housing. Housing First promotes quick resettlement and, in reality, has historically been directed at people who meet the usual criteria for housing insecurity, mainly ignoring the special long-term housing requirements of women. While demonstrating excellent housing and health and wellbeing results, assessments of Housing First in Canada have opted to use populations with a male preponderance and forego the unique experiences of women (Yakubovich & Maki, 2022, p.2589). A concerted effort is needed to improve the well-being of women experiencing homelessness due to overlapping relations between homelessness, physical and mental health, and exclusion and inequality. The health sector acknowledges that the fundamental step in treating well-being is to resolve the structural and institutional factors that cause both physical and mental illness. Long-term improvements for individuals and communities are possible with strategies like Housing First, which offers housing and support facilities to meet their immediate medical needs. Yet, there needs to be a significant development that would include culturally-sensitive services for Indigenous women within the Housing First model (Schwan et al., 2020, p.255). Accordingly, criteria related to gender should be incorporated into housing programs and initiatives for Indigenous peoples. As homelessness amongst Indigenous peoples is a result of historical and ongoing colonialism, the well-being of Indigenous women and their communities is impacted by violence and enduring trauma (Bingham et al., 2019, p.10). Waegemakers Schiff et al. (2016) dictate that the proposals should capitalize on Indigenous communities' knowledge, abilities, and strengths. As part of a deliberate solution to Indigenous homelessness, developing local and structured initiatives is a first and essential step. This would entail integrating resources, creating regional systemic initiatives, and customizing strategies for groups with service delivery difficulties. As part of bigger regional solutions, such plans should incorporate thorough housing and service recommendations to alleviate housing instability in large urban areas and within smaller communities, like reserves. The strategies should also promote research into alternative housing options that use community resources and inventive interpretations of "housing first" approaches within reserves. Indigenous peoples, especially Indigenous women, require focused strategies to overcome complicated legal hurdles in attaining services and assistance on and off reserves. Many reserves or smaller communities additionally need to coordinate their housing and homeless services for victims of domestic abuse (p.81).

By combining some of these recommendations above, I believe that what could aid in Indigenous women's homelessness include creating culturally relevant solutions that focus on the strength and empowerment of the community. No one understands a community better than themselves; hence, any strategy to reduce the homelessness experienced by Indigenous women must be designed and implemented with the participation of Indigenous women. In this sense, emphasizing the creation of culturally-responsive services that underscore care for matters like poverty, trauma and violence, and other issues and circumstances would be beneficial.

As individuals, we can all do our part to spread awareness and acquire knowledge about the historical and ongoing Indigenous issues and heritage. Maybe visiting/volunteering at a nearby women's shelter or participating in advocacy efforts to improve the quality and well-being of homeless Indigenous women can make a great difference. Reconciliation is a process; thus, building a brighter future can start with reducing one's biases and ignorance. As I conclude this blog, I hope you have learned and grasped some information and facts on what homelessness entails and some contributing factors (even if you just took a quick scroll through!). Thanks for taking the time to scroll through this blog!!

0 notes

Text

Did COVID-19 Exacerbate the Problem?

It is almost impossible to discuss women's homelessness, specifically indigenous women's homelessness, without considering the ongoing pandemic's repercussions. The COVID-19 pandemic is linked to increased chances of violence against women, including intimate partner violence (IPV). Along with having adverse effects on health, IPV is a significant factor in women's homelessness, which both causes and aggravates existing health issues.

New evidence indicates that IPV has escalated since the pandemic's beginning due to factors including job insecurity or financial difficulties, service interruptions, and lockdown procedures. Organizations that assist women have found substantial pandemic-related effects, such as difficulties in delivering support (like the need for safety equipment and access to technology) and difficulties in obtaining them (like women that were residing with abusive partners) (Yakubovich & Maki, 2022, pp.2587-2589). Physical isolation and stay-at-home restrictions were implemented to prevent the transmission of COVID-19, but it may have also placed some women at greater risk of suffering from violence. For example, youth, adults, and elders may have had to share small living spaces due to school closures, program limitations, and people's inability to leave their residences. Consequently, this can have harmful financial, physical and emotional effects and worsen existing mental health conditions. Additionally, the issue of overcrowding in residences is further a risk factor for domestic and family violence and the transmission of the illness. While some communities have created shelters for women throughout the pandemic to protect their well-being, which would help lessen the harmful impacts of the lockdowns and self-isolation for those experiencing domestic violence, many communities lacked appropriate housing, urgent services, and sanctuaries. For instance, there are just fifteen facilities in the Inuit Nunangat, which serves 51 remote, fly-in Inuit settlements (Mashford-Pringle et al., 2021, pp.17-18).

As such, the recommendations to remain indoors are hard to abide by for numerous homeless Indigenous women. Because many indigenous women experience "hidden homelessness," those who utilized shelter facilities were more likely to become infected as shelters do not enable physical distancing and run the danger of becoming overcrowded. As such, Indigenous women who experience homelessness or are temporarily housed are frequently unable to secure housing at shelters because of the lack of space or the violence they have experienced, forcing them to live on the streets and leaving them susceptible to illnesses (Palmater, 2020, p.8). Moreover, linking back to a previous post about women's homelessness, the gender-based effects of the pandemic, besides violence, exacerbates issues concerning health (women make up the largest percentage of frontline workers), unpaid labour (like childcare), and economic consequences (as women hold the bulk of low-wage, insecure jobs) (Yakubovich & Maki, 2022, p. 2589). Consequently, it should also be noted that the availability of emergency housing is challenging for anyone experiencing homelessness. This challenge may be greater for Indigenous women, notably because of the unequal dispersion of shelters.

I understand all this information can be hard to comprehend, and you may wonder, what can I do to help? Is one person able to make a change? I will address this in the next post, as well as some other solutions we can employ to help curb this issue!

0 notes

Text

What are Some Housing Difficulties Indigenous Women Must Tackle on and off Reserves?

Housing on reserves, at its roots, contributes to Indigenous women’s social and economic exclusion. Due to a young, rising population on reserves, there is a profound housing scarcity as new property development and maintenance of residential properties have fallen behind the demand (Dyck & Patterson, 2015, p.5). Issues like overcrowding shorten a home’s longevity and increase frustration and violent behaviour (Assembly of First Nations (AFN), 2013). Additionally, overcrowding is associated with a higher risk of spreading illnesses (Robson, 2008, p.72). The photo below states that adult Indigenous peoples are 12.9% more likely to utilize shelters than non-Indigenous peoples. Likewise, overcrowding frequently brings family violence, and domestic violence is rooted in colonial violence sustained by inadequate housing on reserves. In fact, on reserves, 36.8% of Indigenous peoples reside in overcrowded housing units. The problems of existing properties on reserves also reflect poorly on the quality of housing constructions, as 44% of Indigenous peoples who reside on reserves live in homes that require extensive maintenance (Statistics Canada, 2017). O’Donnell and Wallace (2011) stated that, contrary to 7% of non-Indigenous women, 28% of First Nations, Inuit, and 14% of Métis women lived in homes needing substantial repairs off-reserves. On reserves, 44% of women resided in homes that required extensive repairs, and relative to 3% of non-Indigenous women, 31% of Inuit women remained in overcrowded homes. A direct correlation exists between gendered housing issues on reserves and the disproportionate number of Indigenous women experiencing housing instability and hidden homelessness.

The Nishnawbe Aski Nation Women’s Council stated that Nishnawbe Aski Nation communities lack adequate housing, frequently resulting in overcrowding. Due to the lack of beds available, individuals must share beds or take shifts sleeping. This living can be detrimental to people’s emotional and physical well-being as many individuals residing in places like shelters also struggle with abuse, addiction and mental illness (NANTDL, 2018, p.18). The colonial practices used to suppress Status Indians, continuous federal oversight over Status Indians, and the ongoing lack of funding all contribute to high poverty levels on reserves. On reserves, poverty significantly hinders women from asserting their rights on matrimonial assets (MacTaggart, 2016, p.5). In fact, Acts like The Family Homes on Reserves and Matrimonial Interests or Rights Act (MIRA), which permits women to request absolute possession of the land, are made irrelevant, according to MacTaggart (2016), because there lacks enforcement provisions or means to attain legal support on reserves. Consequently, difficulties with the asset value of homes on reserves might result in unequal wealth allocation in an instance of divorce. The partner, most commonly the woman, is forced to search for housing off-reserve with substantially less financial assistance due to systemic poverty and housing scarcity on many reserves (p.8). Consequently, women living on reserves are frequently forced to leave since there are not enough shelters or housing choices available. Women are thus left in highly urbanized environments without substantial assistance to Indigenous-focused services. Issues concerning poverty, little income, and inexperience with systems and policies for securing housing within cities influence their relocation from reserves to urban spaces (Brandon & Peters, 2014, p.22). Indigenous women are more inclined to experience homelessness in urban settings due to these circumstances and are more likely to experience violence.

I talked about hidden homelessness, but you may wonder what it entails. Individuals who live in complex living arrangements, like couch surfing, but do not utilize shelters or transitional housing are said to be “hidden homeless” (Abramovich, 2016, p.88). The photograph below states inadequate housing, survival sex, physical and sexual abuse, overcrowding, poverty, and intimate partner violence are some factors that lead to hidden homelessness. To live, women are likely to depend on transactional and temporary services and are less likely to be found in conventional shelters, drop-in facilities, and public parks. Consequently, hidden homelessness also includes risky tactics used by homeless women to obtain housing and avoid threats from unisex shelters and the streets, which includes remaining in dangerous and abusive relationships and offering sex for housing (Bretherton, 2017, pp.6-8). As a result of its “hidden” nature within public structures, hidden homelessness amongst women frequently goes unacknowledged.

0 notes

Text

The Scale of Women's Homelessness

Before addressing the major issues concerning Indigenous women experiencing homelessness, it is critical to draw attention to some of the problems that affect women's homelessness more generally. While both men and women experience homelessness, women are more likely to experience severe health, safety and well-being challenges. According to Schwan et al. (2020), women face systemic gender-based inequalities concerning domestic violence, low pay and unequal childcare, which all contribute to an increased likelihood of experiencing homelessness. Accordingly, women are more inclined to be employed in contract positions, earn less than men, and spend more on average for rented properties. This is especially apparent for Indigenous women, who make 55.6% or less of what white men do. As indicated in the figures below, women are more likely to reside in inadequate housing and struggle with low income, especially if they are newcomers or racialized (p. 71). We can relate this back to women's intersectional identities, where not only are they discriminated against because of their gender but also for their race, ethnicity, age, sexuality or Indigeneity.

Moreover, due to traditional gender roles, women tend to care for household tasks and provide support for the family in the case of illness and often endure a more drastic fall in income post-divorce or separation (23% for women versus 10% for men). Maternity and child-rearing further increase the likelihood that a woman's career and earnings would be altered, and single mothers suffer discrimination when applying for rental accommodations and childcare (Schwan et al., 2020, p. 71). As the photo attached below shows, 21% of single mothers raise their children in poverty, and the occupancy rate of family shelters has increased by 27% since 2007. These statistics and the others displayed are incredibly alarming!

Consequently, another factor that leads to women's homelessness is the danger of domestic violence or intimate partner violence (IPV). Even though IPV affects individuals of all genders, women are more likely to endure severe IPV in addition to its physical, emotional, and financial effects. Compared to men's homelessness, women's homelessness is typically "hidden" (I will discuss this in the upcoming post!) and can be influenced by IPV. Shelters for women who have experienced violence frequently operate at capacity due to chronic underfunding.

Unfortunately, due to demand, shelters do not have the capacity and capability to care for all. As indicated by the photo above, 82% of women are neglected due to capacity limitations. Despite the knowledge that IPV is particularly prevalent in Indigenous communities, an alarming 70% of northern reserves lack safe housing units or emergency shelters for women in danger (Schwan et al., 2020, p. 72). Moreover, women, especially those racialized and Indigenous, may be more likely to experience assault, state monitoring, prosecution, and child apprehension if they live or remain in homeless shelters (filled mainly by men and have financial and staffing constraints). Most specific accommodations for IPV-affected women are limited to stays of no more than two months. There are few possibilities for longer-term housing, particularly those with continuous services, which are crucial for those affected by IPV. These options include temporary shelters (covering durations of one to two years) and long-term housing (Yakubovich & Maki, 2022, pp.2588-2589). These findings imply that gender-based barriers exist. For women, homelessness has various causes, pathways, circumstances, and effects depending on its context. As a result, addressing how gender-based inequality is ingrained in our institutions, laws, and procedures is necessary to address homelessness and the housing crisis.

0 notes

Text

What Role Does Colonialism Have In Indigenous Women's Homelessness?

Indigenous homelessness can primarily be interpreted as colonial operations that separated and deprived Indigenous peoples of their governmental structures, legal frameworks, territorial jurisdictions, traditions, ideologies, and oral traditions. To understand the realities of homelessness that shape Indigenous women’s experiences, colonialism from its historical and continuous context is crucial. According to Kauppi et al. (2013), Indigenous peoples were not homeless before the onset of colonization. Their culture was built on vast extended families, in which everyone was taken care of and embraced; hence, every individual would have a home. However, due to colonization, the Indigenous philosophy of egalitarianism was destroyed, and Indigenous peoples were removed from their land. Consequently, on a broader scale, Indigenous peoples have been rendered homeless (p.44). As such, a continuing crisis of racial and gendered violence directed toward Indigenous women increases the risk of homelessness. The legacy of settler colonialism, expulsion, and dispossession marked the beginning of this violence. A critical factor in demonstrating how Indigenous women have been oriented within Canadian society is the execution of the Indian Act of 1876. The Act enforced gender-based policies against Indigenous women and removed them from their positions as matriarchs within their communities utilizing the legal frameworks of the Indian status. As such, Indigenous communities were forced to accept Eurocentric patriarchal values and demeaned Indigenous women by using discriminatory language and policies that placed women as inferior to men. The gendering from the Act dispossessed women from their lands and assumed their registration as “Indian” as per their husbands (Ancil, 2018, p.7). In this respect, the collapse of the matriarchy is a highly noteworthy aspect of Indigenous cultural degradation and homelessness. For instance, in Cree communities, women are known to manage their homes and meet their families spiritual and physical needs. Women are respected and inexorably tied to the ideals of the private and public spheres. Colonization and other matters imposed the patriarchy, leading to the current period where Indigenous women are considerably devalued (Schwan, 2020, p.35). As such, Indigenous women’s status as members within their communities and of the larger Canadian society has been weakened.

For women residing on reserves, their access to housing is firmly rooted in the disempowerment of the Indian Act, which also perpetuated housing instability and homelessness as a manner of colonial domination. The arrangement of land ownership on reserves significantly influences Indigenous women's housing access. The colonial project forced non-Indigenous notions such as private property upon Indigenous populations, which were designed to favour Indigenous men over Indigenous women, and the sexist colonial ideals of the Indian Act reinforced it. The Indian Act altered how men and women interacted with each other in Indigenous communities, instituting patriarchal attitudes and violent social norms. The intergenerational and catastrophic trauma caused by the removal of Indigenous women from their communities and the dissolution of Indigenous families has been transmitted through generations. When paired with other socioeconomic issues, housing on reserves contributes to the perpetuation of colonial violence (Schwan, 2020, pp.156-157). Besides the historical manifestations of settler colonialism, there is also an ongoing prevalence of these manifestations. In fact, as noted by Schwan (2020), the history of resettlements, residential schools, the Sixties Scoop, high incarceration rates and the child welfare system is transmitted through generations and causes intergenerational trauma. This trauma affects individuals of every age and is reframed with difficulties like substance abuse, addiction, or suicidal tendencies due to the distress of ongoing colonial oppression (p.153).

0 notes

Text

What Is Homelessness? Who Experiences Homelessness? Who Is Most at Risk?

When we think about homelessness, what comes to mind? Maybe you are wondering how they got into this situation. Perhaps you are unsure what to say or do when someone experiencing homelessness approaches you for spare change. While these initial thoughts are common, let us delve deeper into what homelessness entails. Homelessness is indeed a political concept by nature. Who accesses resources and is provided with housing depends on how homelessness is characterized. Homelessness has a long history of having contested definitions. Some definitions span from "street" homelessness to those "at risk" of experiencing homelessness. According to Clifford et al. (2019), homelessness is a continuum that includes anything from “rooflessness,” wherein people essentially reside on the streets, to housing precarity, wherein people reside in underwhelming, congested, and temporary housing (p.1125). In accordance, Burns et al. (2018) suggest that homelessness can entail

Unsheltered: includes those without a place to live, residing on the streets or perhaps in locations hardly designed for people

Emergency Shelters: includes those residing in nightly homeless shelters and facilities for anyone experiencing domestic violence

Provisionally Accommodated: includes those whose housing is transient or has no land ownership and is ultimately "couch surfing" or residing in their car

Substandard Housing: includes those who are "at risk" and experiencing financial disparities or whose living conditions do not conform to codes and standards (p.172)

Homelessness affects women in each of the areas mentioned above. However, these definitions frequently reflect Eurocentrism and cease considering Indigenous definitions and ways Indigenous women perceive and experience homelessness. They also overlook how violence, harassment, and mistreatment inside the household produce homelessness and how institutional and structural inequalities impact Indigenous women (Schwan, 2020, p.57). As such, Bingham (2019) articulates that Indigenous definitions of homelessness derive from the detachment and alienation from kinship links and connections to the earth (p.8). Considerably, it is essential to be mindful of the links between displacement and the absence of social and spiritual relationships among Indigenous women.

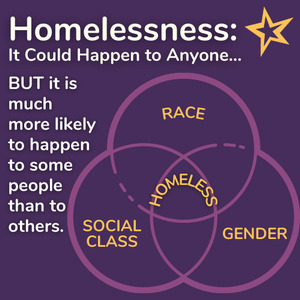

Now let us explore who experiences homelessness. Unfortunately, there is not a straightforward answer, as the reality is that anybody can become homeless for a variety of factors. As a result, homelessness might occur to you or others close to you. However, while homelessness can be a risk for anyone, some people are more susceptible to experiencing homelessness than others. In this sense, we can interlock these ideas with Indigenous peoples, especially Indigenous women. For example, the infographic above explains how Indigenous peoples are eight times more likely to experience homelessness than their non-Indigenous counterparts. Now you may have some questions like: Why is this? What makes Indigenous peoples more susceptible? Do Indigenous women have different experiences of homelessness compared to non-Indigenous women? Do not fret; I will explore these questions in upcoming posts.

0 notes

Text

Why is it Important to Look at Homelessness Through an Intersectional Lens?

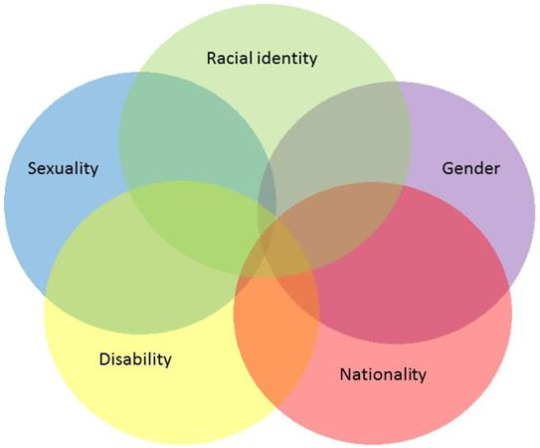

Homelessness could happen to anyone, and some individuals are more likely to experience homelessness due to structural, individual or a fusion of both elements (I will get more into this in the next post). In the Canadian context, women are more likely to encounter homelessness and its dire effects (Milaney et al., 2020, p.40). However, women and girls who experience homelessness are vastly downplayed. How we identify, quantify, and address housing accommodations and homelessness obscures the plight of women who are homeless, especially Indigenous women. The disparities women confront, and the intricacy of these circumstances will not be visible if homelessness isn't understood via an intersectional lens. The lens seeks to comprehend how various types of marginalization and inequities interact within women's lives according to their overlapping social locations (such as gender, race, sexuality, class, ability or Indigenity). As such, the lens acknowledges that 'identities' are not identical for all women and that there are overlapping difficulties and injustices that women experiencing homelessness face according to these specific social locations. For instance, women's entry into appropriate shelters is not only shaped by gender, but a multitude of social locations, including race, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and life experiences (Schwan, 2020, p.47).

Applying an intersectional lens aids us in understanding and recognizing the several identities and institutional structures that formerly and currently undervalue women in the context of homelessness. The fundamental element of intersectionality is that people do not have a single identity; their associations with other groups give them multidimensional identities. History, social relations, and power systems influence such identities. The features of inequalities and power must be disclosed to assess a person's response to their lived experiences. Recognizing how gender, race, and Indigenous status interact in subtle ways to explain why Indigenous women disproportionately experience homelessness is critical. The historical oppression of women, notably Indigenous women, is frequently caused by these intertwining links. For instance, Indigenous women will have different experiences with homelessness than White women because they are both Indigenous persons and Indigenous women (Levine-Rasky, 2011, pp.241-242).

0 notes

Text

Welcome!!

As part of an assignment, I have decided to investigate Indigenous women’s challenges when experiencing homelessness. This blog seeks to showcase how, and to what extent, homelessness impacts the health and well-being of Indigenous women within Canada. This blog can further be framed as a study into why women experience homelessness and what we can do to prevent them from experiencing homelessness. As a political-science student, issues about gender issues, especially concerning racialized women, are of great interest to me; hence, this blog will explore the various nuances around racism, sexism and gender equality within the general phenomenon of homelessness. How this blog will work is that each post will cover a separate topic; however, these posts are all interconnected with the main topic: the challenges concerning women’s homelessness. While the subject matter may be difficult to read and interpret, discussing and emphasizing complex issues related to women’s homelessness is imperative. As a non-Indigenous woman, I do not seek to speak for the community or try to understand the complexities of Indigenous women’s lived experiences thoroughly, yet I do believe that recognizing the obstacles placed in front of Indigenous women is merely a small step forward in finding solutions to combat the issue; hence, I seek to stir your curiosity about this in that it is highly prevalent within Canadian society. As a side note, the Women’s National Homelessness and Housing Network (WNHHN) and Anduhyaun Inc are excellent resources for further information or support! Here are the links: https://womenshomelessness.ca/women-girls-homelessness-in-canada/ & http://anduhyaun.org/

1 note

·

View note