Text

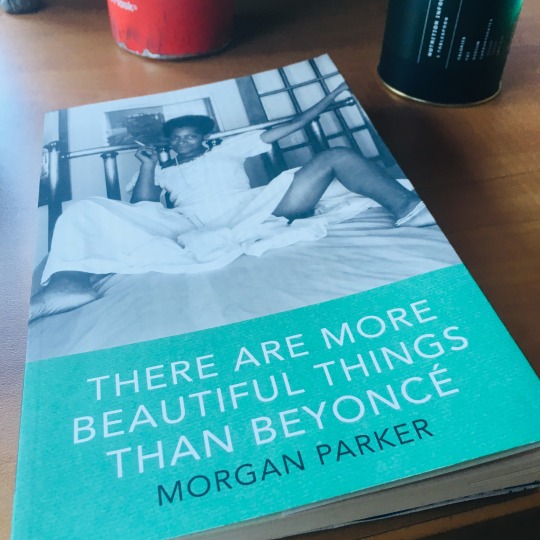

“There Are More Beautiful Things Than Beyoncé” by Morgan Parker

This book had been years coming in my collection. Its name rang out inside me when I felt its titular sentiment — that the popular worship of Beyoncé is overblown — and whenever I thought of it, I felt a spark of solidarity.

Of course, this is not a book about Beyoncé — and in fact, this is not even a book that is very critical of Beyoncé. Instead, Beyoncé acts as a literary device throughout — a mouthpiece, an amulet, a proto-idea that shapeshifts to meet Parker’s endless need to talk, sing and moan about race, class, democracy, depression, music and drugs. It’s a brilliant move.

I’d like to start more broadly by commenting on Morgan Parker, because she strikes me as an outsider among insiders. In my head, Parker is of the generation of contemporary poets that includes Danez Smith, Franny Choi, Ocean Vuong etc. … she’s decorated with a Pushcart, she co-curates a reading series, she performs with Angel Nafis as part of The Other Black Girl Collective. Her poetic career is bedazzlingly active — so why don’t we talk about her more?

By which I mean: there seems to be a kind of halo around young poets like Ocean Vuong, who — and I say this with admittedly limited experience of his work — turn the harrowing vine-tangle of identity into a kind of rhapsodic experience: a thing worth looking at because it is beautiful. (Here is an example, from Vuong’s “Tell Me Something Good”:

Snow on your lips like a salted

cut, you leap between your deaths, black as a god’s

periods. Your arms cleaving little wounds

in the wind. You are something made… )

There’s no arguing that Vuong’s poem is beautiful; my issue is with how the beauty is used. Vuong’s poem here seems an extension of the (frankly depressing and oppressive) idea that “foreigners” can make their stories worthy through pathos, pity and craft — i.e., hard work and relatability. If the sentiment sounds familiar, just tune into the way mainstream conservatives these days talk about immigrants: I don’t have a problem with immigrants writ large, I just prefer immigrants who work hard, keep their heads down, are pleasant to my children, are generally agreeable…

Anyway, it’s not fair for me to pass such a blanket judgement over Ocean Vuong’s work, and that’s for another review. But insofar as Morgan Parker is concerned, she parses the work and space of otherness in an entirely different manner. Similar to Claudia Rankine of Don’t Let Me Be Lonely, her argument is this: I won’t “fix” myself for you. I won’t try to make myself beautiful. I will tell the (magical, insatiable) truth as it is, and you will have to try to keep up. Because I am too tired to bow down, to construct something for you, to micro-manage. Parker’s poems are for haters of micro-management; they offer big gestures in small bottles.

Consider the opening lines of the opening poem, “All They Want Is My Money My Pussy My Blood”:

I am free with the following conditions.

Give it up gimme gimme.

Okay so I’m Black in America right and I walk into a bar.

With this bold opening, Parker’s commitments are clear: she will demand things of the reader (“give it up gimme gimme”) and she will clearly demarcate what commands her attention and respect (“I’m Black in America right”). And with this begins what I can only describe as a chimeric collection, more warm-blooded fantasy animal than diorama; more occult message written in glitter than typeset monolith. She scrounges from jazz, RnB and pop to fill her pauses. She is unrelentingly new instead of subtle. I like it:

I am a dreamer

with empty hands and

I like the chill.

I will not be attending the party

tonight, because I am

microwaving multiple Lean Cuisines

and watching Wife Swap…

(“Another Another Autumn in New York”)

—and the sincerity of her materials shine through. (To continue this silly dogfight I’ve set up, compare the above with Vuong: “Air of whiskey and crushed / Oreos.” Parker’s allusion to pop culture delights; Vuong’s seems like an add-on, a sprinkling of something inappropriate on top).

But wherefore is the source of all this magic? I would say in what Sun Ra called “liquidity.” For example: Parker was best when R and I read her aloud on a grassy slope on Belle Isle in Detroit. There we were, in a historically Black city, in what I can only describe as a “public paradise.” Ducks waddled by and folks of all stripes strolled in front of us beside a small man-made lake. As we read Parker aloud, we laughed with her and from within her work — as though her words gave us the ability to access our inner performers, delivering punchlines (“I don’t know / when I got so punk rock”) and casting personal spells (“I breathe / dried honeysuckle / and hope”). We felt for her. And we wanted to continue feeling for her. All things told I had a moment of genuine orality with her work — a glimpse of what poetry must have felt like when it was shared, sung and social by default. This is a book that radiates the energy of the collective, that asks you to recognize it — and does not over-demonstrate.

So, in this false dichotomy, one might pose:

LIQUIDITY: ORALITY, SOCIALITY, LONG STANZAS SHORT LINES

against

SOLIDITY: WRITTEN, INWARDNESS, SMALL FORMAL STANZAS LONG LINES

In the former, you have the world of most popular songs, particularly jazz; in the latter, you have sculpture and “high art.” Perhaps this is why Ocean Vuong’s work has garnered him endless praise and attention, and most of us look askance at Morgan Parker’s messiness, silliness and genuine emotional bravery. She rambles, yes, but her rambling challenges the very idea of boundaries — of “discipline” as a set of limits, of borders we set for ourselves, however beautiful.

Finally, I will say this, as it’s becoming a theme in my reviews. Parker’s poetry feels affectively liberated. She is funny as well as ashamed. Take, for instance, this amazing section of “RoboBeyoncé”:

The reason I was built

is to outlast some terribly

feminine sickness

that is delivered

to the blood through kale

salad and pity and men

with straight-haired girlfriends

[…]

Nothing aches in here

It’s a quiet, calculated shame

Part of the power in these lines is the fact that despite the sprawling, messy energy of Parker’s poems, formally they are incredibly demanding due to their short lines. Parker does not give herself the liberty of overusing the form that has, frankly, become a meme among young poets — the poem composed of long couplets, like Vuong’s poem above — and instead prefers her poems one long connective muscle. The result is propulsive and exciting, like watching a figure skater do tight turns on the ice. She is insightful but also — I dare say it — entertaining. But in the wry, dark way that comedians have that communicates, “Look, I don’t care if you don’t like me. Most of the time, I don’t like me either.”

Which is not to say that Parker’s work is perfect — like the aforementioned figure skater, she does often fall short of her ambitions and can write poems that don’t hold together — often using the couplet form above. I think her work is best when it acknowledges its liquid merits, and doesn’t try to stand with too much air around it.

Overall:

9/10 for sheer spillage of fantasy radioactive plasma

Read If You:

-Think it’s lame that Beyoncé talks so much about her “rock”

-Miss the energy of cities like Detroit

-Have friends you want to read with and you are all getting tired of the bone-dry landscape of contemporary poetry which is really just about “passing” politics and making pain beautiful and omg what if pain is NOT beautiful what if it is just pain motherfuckers what if leaving the party is political too goddamn

Further Reading

Don’t Let Me Be Lonely by Claudia Rankine -- deep classic, prepared the soil for Parker

BONUS: Things To Do In Life That Are Not Poetry

Inspired by Morgan Parker, try:

1. Starting a flashy project then abandoning it on purpose

2. Making a cocktail after a song by a Black American musician

3. Getting in a tub of ice cold water and listening to Kendrick Lamar’s DAMN. while doing one’s nails without shivering

Feverish and anything but lonely,

Michu

P.S. A last thought while in the shower. Morgan Parker’s poetry is relentlessly self-aware. But I think what we mean when we say “self-aware” is actually not “being aware of the self” but “being aware of everything but the self” -- i.e. seeing one’s pronouncements as part of a larger (in Parker’s case historical) context. When Parker sits down to multiple Lean Cuisines and Wife Swap, the irony she projects comes from a deep rootedness in the idea that this is a thing that people do: skip parties to self-indulge in everyday, consumerist ways that our higher selves disapprove of. It’s not that her sentiment or self-report is inauthentic, but rather that it is aromantic -- it doesn’t presume that her experience hits on some prized singularness about being human. And I like that; I find it smart and honest at the same time, which is a rare combination -- not just in poets, but in people.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

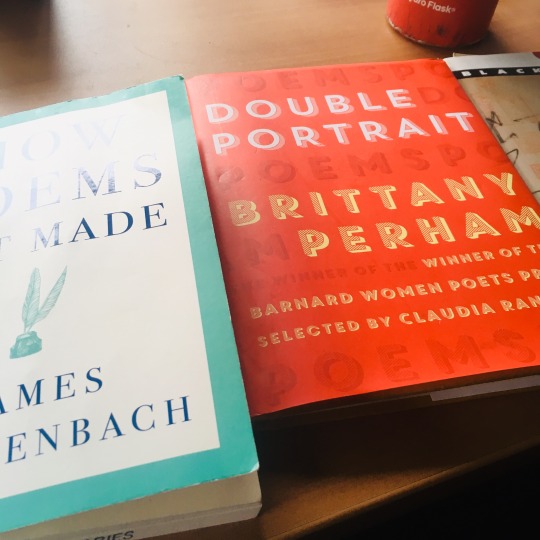

“Double Portrait” by Brittany Perham

Lately, I’ve been lounging with James Longenbach’s How Poems Get Made, and it’s colored the way I’ve been reading the poets available to me. In particular, Longenbach’s chapter on voice describes how “[w]hen we say that a poem presents us with a strong sense of voice, what we’re often in fact saying is that the poem sounds like Donne” (39). And he goes on to describe Donne’s almost supernatural ability to create the impression of a human speaker through skillful variances in diction and the sound of words.

{In a particularly gripping section, he uses the lines of later poets to demonstrate Donne’s influence; listen in the following lines for the voice that seems to animate them:

Robert Browning: But do not let us quarrel any more.

Marianne Moore: Why so desolate?

D. H. Lawrence: You tell me I am wrong.

Bidart: What should I have done?

Ashbery: Time, you old miscreant!

Ellen Bryant Voight: I made a large mistake I left my house

…if these examples sound alive to you, notice the shapes to which they lead the mouth; notice the natural variance therein… } (38-39)

All of which is to say, I was thinking about voice when I picked up Perham’s book.

First of all, it’s worth noting — as the cover rightfully boasts — that this volume was chosen by Claudia Rankine (!) as the winner of the 2016 Barnard Women Poets Prize (the last winner was Sandra Lim, chosen by Louise Glück for The Wilderness). And an honor well-deserved: Perham’s poems are disarmingly frank without losing their playful edge; as an example, the first poem in the collection involves the idea (and actuality) of vomiting blood.

How does a collection that begins with the idea of catching your father’s bloody vomit in a “bin,” how does such a collection still manage to project such a sense of dignity, of self-collectedness?

If I may, I think the answer is twofold:

1. AURA OF LIVED EXPERIENCE: Perham’s poems ooze an aura of lived experience — of someone who has been through what she reports and has thought about it for a fortnight or two. In particular, it was a gift to experience her insights about what is major and what was minor, so to speak, as in her fantastic song about daily life with a partner:

I read your new book

it’s great now I’m sulky

I get a new job

insurance!

it’s great now you’re sulky

but also you’re happy I’m happy

I’m happy you’re happy

It’s payday (26)

Taking up the gauntlet of many illustrious women poets before her, Perham magnifies the domestic for the drama it always is: a stage where shellfish, champagne, and paper towels mark the boundary between two individuals laboring over the project of togetherness.

This kind of book resists the canon for the precise way in which it resists the canonic judgement of what is major, and what is minor. Perham’s insistence on foregrounding the everyday is also her insistence that our lives are worth writing about: “There’s no use putting on perfume / for a Skype conversation” (31). Her ability to point out the obvious, the familiar is actually extraordinary, and constitutes a genuine poetic gift.

2. FORMAL INVENTIVENESS: The other reason Perham’s work is enjoyable is that Double Portrait reads like a romp, a display of inventiveness that extends beyond content (the playpen of many a contemporary poet) towards form. (In this way, her work recalls to mind the form-wrangling work of Danez Smith.)

Take, for example, the litany in the “Third Series” that begins:

9,885,998 of us watched the clip of a hatchling duckling

One of us went to podcasts

One of us heard the voices of old men and knew poetry was there

One of us was male, male (55)

Or this poem, which weaves quartets in Dante-esque shifts;

I’d be be waiting for you to come home.

Amy says, A fondling session comes with the inevitable risk —

Spring will come and

I’ll be alone in this little box of a room.

Amy says, A fondling session comes with the inevitable risk

of being laughed at—is it habit, is it altogether voluntary?

Alone in this little box of a room,

a “fondling session” seems like everything! (75)

Weaving the ends of lines with acumen that reads as naiveté, an endless process of discovery, Perham lives up to Rankine’s incisive observation: “This is the world before exhaustion and cynicism overtakes the lyric.” In a world of exhaustion and cynicism, turning to others — mirroring them, attempting to “address the Thou” (77) despite everything — may be one energetic salvation.

Finally, I had to ask myself while binge-reading this book, why is Double Portrait not at all like Dorothea Lasky’s poems about kitten videos and so on? I think it has to do with my first point — the insight about the the genuine major and minor, the forthrightness of what feeling is genuinely bound up in. Perhaps it is fair to say that Perham’s work displays a wider, deeper palette of emotion, including the (rare!) shades of filial piety (9), forgiveness (3), uncertainty in the midst of fidelity (18), kiddish obsession (20) and the feeling of willingly becoming a stranger to a past lover (74). These are real emotions — and we judge their reality by the way in which they resonate with our own lived experiences. Said in another way: these are poems that resist the textureless digital world, that bristle and break the surfaces that flatten experience into ironic reportage.

Overall:

8/10 for intelligent jolliness

Read If You:

-Are wondering who’s doing what in the world of poetic form these days

-Miss your mum

-Have been in several relationships and aren’t married yet; where are you even? are you on the “train of living” that everyone else seems to be on or are you, like, an accidental drifter? should you change your name? is it ok to feel what you feel? (Perham: yes.)

Further Reading

How Poems Get Made, James Longenbach

BONUS: Prompty Memes for Poetic Fiends

Inspired by Brittany Perham, try writing:

1. A contemporary ghazal

2. A poem in which quatrains, tercets or any other stanza form “weaves” in the Danteseque way above (ABAB, BCBC, CDCD etc.)

3. A piece that explores a duality that isn’t the duality between lovers, family members, or citizen/state.

… ok, to the siren call of dinner.

With soy-soaked tempeh,

Michu

(I dog-eared poems I loved.)

P.S. I forgot to tie up the loose end about Longenbach’s voice. Perham’s poems also display a lovely sense of voice, though her tools to accomplish this involve content as much as diction and assonance. Peace!!!

0 notes