Text

78/52: TIFF Film Circuit Fall Release Schedule

Alexandre O. Philippe

Principle Cast: Peter Bogdanovich, Jamie Lee Curtis, Guillermo del Toro, Danny Elfman, Elijah Wood, Walter Murch, Marli Renfro

Distributor Details

Distributor: Kinosmith

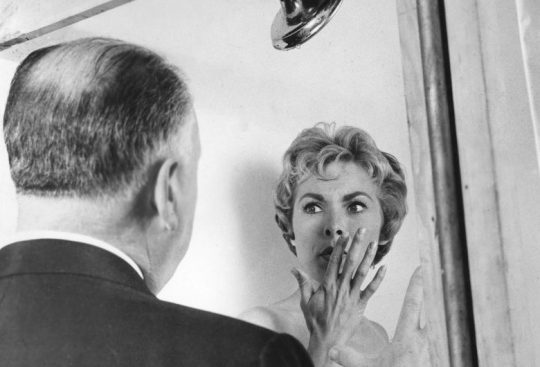

This new documentary feature 78/52 , from director Alexandre O. Phillippe (George Lucas Vs The People), deconstructs the iconic shower scene of Hitchcock’s monumental film, Psycho. Film historians, directors, and actors come together to analyze the sequence, uncovering the mastery of Hitchcock’s technique, and the historical significance of this scene in pop culture.

Over the course of 90 minutes, the film examines the filmic content and cultural context of one of the most famous scenes in film history. With the 1960 release of Psycho, Hitchcock pushed cultural and visual boundaries that defied audience expectations with the on-screen murder of studio star, Janet Leigh, in the first act of the film. Commentary is offered by familiar faces like daughter of Janet Leigh, Jamie Lee Curtis (True Lies, The Tailor of Panema), actor Elijah Wood (Paris Je T’aime, The Lord of The Rings), sound editor Walter Murch (The English Patient, The Godfather), and Marli Renfro who played Janet Leigh’s body double for the original scene. Each of Philippe’s interview subjects provide their own personal insights, unpacking every element of Hitchcock’s direction, and revealing what made this moment such a pivotal point in American and world cinema. Through their collective insight, some fascinating truths emerge. Notably, the time and craft that went into filming; Hitchock spent 7 days perfecting the scene, using 78 camera set ups and 52 cuts, an obsession that resulted in one of the powerful examples of visual cinema.

Philippe places this scene in a greater cultural context of the 1960’s, pre-civil rights and at the brink of cultural political change, and demonstrates how Hitchcock uses his film to reflect themes of family and safety in America. Nothing at the time of the film’s release showcased death so intimately, and with Janet Leigh’s death, Hitchcock made murder an acceptable part of cinema, inspiring generations of filmmakers to come.

78/52 is an engrossing examination of this seminal moment in American film history, and an insightful study of its lasting impact on cinema. Hitchcock’s fastidious attention to detail is recognized by Phillipe, who gives the scene perhaps as much of a close look Hitchcock himself gave in creating it.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Red Turtle.

“Look deep into nature and then you will understand everything better” - Albert Einstein.

There is no thought without expression, no communication without language. Michael Dudok de Wit’s and Studio Ghibli’s message, however profound and important it may be, does not really exist unless it can be expressed through some form of language. However, how can one go about communicating a story without any dialogue? Or rather, how can an audience read a film that communicates without words? Dudok de Wit lets us read this film through his film language, that with the precision of the animated craft, can be perfected exactly to how he intends this story to be read. In this film, communication is not limited by any verbal expression; what we are reading instead are landscapes, characters, colours, lines, and details within his drawings. These subtleties offer all the thoughts, words, and ideas that the characters are unwilling to utter.

To watch Dudok de Wit's “The Red Turtle”, is to watch a filmmaker in control over the visual language of the film that his ideas presuppose. This film is carefully constructed drawing by drawing, and in watching this film, one immediately feels like they are in the hands of someone who knows precisely how they would like to tell you their story. Although communication is not verbal, it is still effective and impactful. Perhaps even more so, as it uses the universal understanding of image without language.

The sudden opening scene gives us a man shipwrecked from a boat we do not get to see, and tells us nothing about his past. He is offered by the ocean to the viewer as a blank canvas that we may impose ourselves onto. The island he is stranded on is beautiful, lush, even peaceful, yet the man is only able recognize it as an entrapment. Despite all of its natural wonders, we watch the man relentlessly attempt to escape the island so that he may rejoin the unknown civilization of his origin. Then we are given the perceived antagonist, the Red Turtle, who is consistently destroying the boat the man has fashioned from bamboo. Dudok de Wit repeatedly shows the limitations of man, and the ability that nature has to humble us. The man is stripped bare, literally and figuratively, and without the technologies and the masses of people of the land that he presumably comes from, his limitations are revealed. But while he tries over and over to create bigger, sturdier, and more advanced boats, it becomes clear that his enemy is not nature, but his perspective. While he builds a boat by day, he dreams at night of building a bridge. One that joins the man with the ocean, where he suddenly begins to take flight. Smoothly gliding over the bridge, transcending his situation. This is perhaps the most literal metaphor that Dudok de Wit provides, encouraging man to follow their natural instinct to unite with the earth to reach transcendence. It informs us that no boat, is going help him overcome his obstacles.

What separates Dudok de Wit from other filmmakers is his ability to generate these profound ideas with the animated craft. He then weaves these ideas together throughout the film, over and over, using lines, colour, symbols and signs as his form of language. His drawings are crafted so to reveal the emotional intricacies of his subjects, thereby distinguishing his characters from the cartoony characters typical for the medium.The simplicity of the lines and colours used on the animations, allows a viewer to focus on their internal subtitles, and not their external flare. What Dudok de Wit does throughout the film is blend this simplicity with vivid detail, a way for him to capture empathy through the audiences projection of themselves upon the character, and reality through the textured and unpredictable nature of the island. Through this unique duality, the viewer can import themselves into this world by aligning themselves with characters that are left fairly vague in their physical appearance. Without language or verbal expression to give the man a sense of humanity, his movement is given familiar idiosyncrasies. Like reaching to the bottom of a pond to feel the sand on your feet.

We are shown the basic tasks that another filmmaker might not include, like the tedious repetition of the man building his boat, one bamboo stick at a time. The man is also given to us as imperfect - another way to relate to him and perhaps a technique for Dudok de Wit to show us our own flaws. We relate to his anger at the turtle, we understand why he attacks it. Yet this scene gives the viewer no gratification, rather a remorse for our selfishness. This is because Dudok de Wit, following suit with Studio Ghibli tradition, incorporates the idea of animism - the notion that a spiritual presence exists within all of nature. The turtle is given a soulfulness that we recognize much easier when it takes the form of a human woman. Immediately the audience, and the man, are given the ability to see how much we have damaged this relationship and how imperative it is to repair. Through the personification of the turtle, we are given an empathy for nature that we often times lose sight of. That the man too, has been guilty of.

A notable trait of this film is that there is no true antagonist. The binary code that is often used in film to inform us of what is ‘good’ and what is ‘bad’, is left out here. We see a gruesome example of man’s willingness to destroy in the name of human progress with his murder of the Turtle. He is trying to build a boat to get him away from the island but nature keeps holding him back, not allowing his progress and his return to civilization. He comes to the turtle and with a forceful stroke, he hits the turtle over the head with a bamboo stick. He then flips the majestically large turtle onto its back, leaving it helpless, a clear example of man's ability to manipulate nature to his own benefit. We see the turtle on its back, in the scorching sun, only feet away from the cool ocean without any ability to save itself. It lays there peacefully, un-angrily, and defeated. This moment of brutality was damaging, but repairable. Similarly, a tsunami strikes the island, tearing down all that this family has built and nearly killing the man. The man and the turtle, are both capable of tenderness as well as savagery. Both can be as brutal as they are kind. Dudok de Wit shows us that there is no one against the other, no man versus nature in this story. Rather these two forces, are bonded through mutual love and respect that is shown throughout the second act of the film. Not only does Dudok de Wit encourage this relationship, but he pays particular attention to it. The film is never about the man winning, but it is about him adapting and growing to a world that isn’t built around his wants. He in fact, is never able to return to his home, but the solidarity and connection that he has forged with the world is gives him spiritual liberation.

The son of the red turtle and the man, is given as a representation of man’s potential. Born of both man and earth, he is equally capable of swimming great lengths through the ocean with the grace of a sea turtle, and showing curiosity for human invention. Dudok de Wit does not favour nature over mankind. To him, these forces are not in opposition at all. And with the son, we see these two forces working together in harmony. We see his human-spirit in the son’s early discovery and fascination with the glass bottle. This glass bottle is the single piece of human technology that remains from his father’s civilization, and throughout the film we only see the young boy alone using it or finding interest in it. Dudok de Wit uses one of the most basic elements of human technology, a bottle, as a symbol of human's instinct for technological creation.

It is given a beautiful moment of rediscovery after the tsunami hits the island; the boy finds the bottle for the second time, in the sand of the drinking pool he once used. This shows us that the human spirit for discovery and progress cannot be broken, and should not be. Beneath the rubble, the delicate glass bottle is perfectly intact, like the spirit of mankind that remains inside the boy. It is after this moment that the boy decides to leave the island. Dudok de Wit leaves the purpose for his departure ambiguous, but his satchel seems to imply a journey. The boy is seeking to find the world, the world that his father drew for him in the sand, full of people, animals, and glass bottles. And Dudok de Wit makes the boy successful in this quest unlike his father before him, because rather than building a boat, the boy is a bridge. This theme of rebirth is something very familiar to Studio Ghibli, as well as Japanese film. Massive spectacles of destruction followed by hopeful rebuilding has been a theme in Japan since the trauma of the nuclear bombs. To deal with the despair of the nation’s consciousness, hope for Japan’s rebirth was given through film. Man and nature are mutually destructive to each other, and from the years of conflict between these two forces, the young boy acts as a hopeful symbol of unification. While man has broken its relationship with the earth, it is able to be repaired.

Dudok de Wit urges us to redefine what we currently see human progress to be. It is often defined now as, scientific discovery, technological innovation, efficiency, ease - technologies providing an answer to the world’s problems. But Dudok de Wit challenges this notion, arguing instead that not only our progress, but our survival is dependent on this intrinsic relationship man has with the earth. That like the man, we cannot harness nature and manipulate it, or treat is as an enemy to our existence. This idea will never be successful. Rather, man should work with nature, allowing our progress to follow the natural rhythm of the earth.

Our connection to the life we think we have, is but small in the face of our much larger spiritual relationship with the earth that informs our human experience. This theme is filtered through other moments in other characters, until this theme becomes solid. The Red Turtle is not Dudok de Wit’s repudiation of human's desire to achieve progress through technology, but rather a suggestion to re-realize the importance of nature and our relationship with it. This theme of unification with nature, is also echoed in Dudok De Wit's unifying language of animation. Through lines, colour, and movement, he allows audiences of all languages to be united in one similar experience. This film explores the unique perspective that an animated and dialogue-free film can gift to a film goer, much like the perspective that a new relationship with the earth would give us, and what kind of new world that perspective allows us to see.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

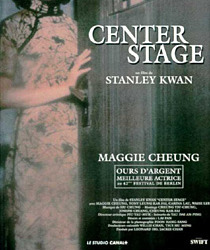

Center Stage and Nostalgic Postmodernism

Stanley Kwan’s 1992 film “Center Stage” tells the story of the famous Chinese silent film actress, Ruan Lingyu. Reaching immense fame at the age of 16, and the sudden end to her life at 25 has made Ruan and integral part of China’s film history. She is known as one of China’s most talented actresses for her immersing emotional performance in the pre-sound era of the 1930’s (Farquahar 253). In the years that passed between Ruan’s death and Kwan’s film, Ruan became a mystified character in Chinese legacy. Kwan’s film attempts to revive Ruan’s image through a remarkably realistic depiction of Ruan’s life. “Center Stage” comes at a time in the 1990’s when China felt an immense nostalgia for their cultural past, and the film attempts to bridge this gap between the past and present with Ruan’s story. The film is notably of the nostalgia film genre, and not of the similar heritage film genre. This is because it longingly looks back at China’s 1930’s past, suggesting through Cheung’s character that the past is more significant and attractive than the present (Hjort 28). It also suggests that Chinese culture has been subject to the same fate as Ruan, tragically and suddenly disappearing into Chinese history. The film was produced during a postcolonialist Hong Kong and postsocialist China period, but explores China’s vastly different past in attempt to understand the political climate of the 1990’s (Cui 60). Approaching the end of the century, China was transforming from the affects of globalization and a changing political climate. Just before the China gained control over Hong Kong’s sovereignty in 1997, Hong Kong was in a liminal state politically and subsequently, culturally. In this medial time, with shifting cultural values and the emergence commercialization, China developed an unstable identity that long to be secured. Films thereby sought to make sense of this new emerging China and find its new identity by looking at it’s past through a specifically postmodern lens. This desire to solidify a new cultural identity was perpetuated by the Hong Kong New Wave Cinema, a style that inspired Stanley Kwan and this production (62). In “Center Stage”, Kwan looks to the mythicized life of Ruan Lingyu to explore these issues of cultural identity. The time of the films production creates a consciously postmodern presentation of the past with three representations of the past: Ruan’s story told through Maggie Chueng’s performance, historical film clips, and a self reflexive present day consciousness of the film being made. These three modes of storytelling come together to create a distinctly postmodern representation of the past. Kwan decision to explore China’s history through a female character has come to be an auteurial marker of his films, and also speaks to the transforming role of women in China’s postmodern society.

In a descriptive documentation of the production of “Center Stage”, the films researcher Jiao Xionping reveals how the search for historical information of Ruan’s past lead to the film’s unintentional postmodernism. Kwan and his production team collected information from newspapers, biographies, and books that focussed on Ruan’s film career. Kwan’s desire for an accurate depiction of the actress lead him to reach out to Ruan’s godsons for a parents diary that included an entry on the night before Ruan’s suicide. The crew conducted interviews with older crew members who worked with her in attempt to construct an accurate depiction of Ruan’s off-screen personality. With this extensive information that was gathered, Kwan is able to provide a Chinese audience with a satisfyingly truthful representation of their beloved actress. Kwan recognizes the importance of providing Chinese viewers with an accurate portrayal of the actress as she is such an integral part of China’s cultural history and a source of pride. After gathering this information, Xiongping describes the crews confusion with formatting the film. Initially, Kwan wanted to present the film through a stories-within-stories style. But being too complicated, Xionping suggested creating a documentary of the films production process to decide later whether to use it or not (Xiongping 6). The crew ultimately decided to intercut the film with historical and documentary footage, making the film one of Hong Kong’s more complex and sophisticate productions. The film’s production is quite unusual and can be considered as a collaborative production between director and researchers. It’s artistic complexity and pastiche-like quality is beyond Kwan’s original intention, but works in its favour due to the period of its release. Xionping notes that “Center Stage” is a very nineties film, “In the movies of the fifties and sixties, all that was needed was an interesting plot, but in the nineties, in addition to this, the film should also include contemporary people’s feelings and a multifaceted understanding of the world” (Xiongping 7). The film goes beyond the story of Ruan’s life, but reveals her importance in Chinese culture, different perspectives of her, and compares her to the currently famous Chinese film actress, Cheung. Through Xiongping’s description of the production process, it seems that “Center Stage” originally intended to create an accurate and in depth depiction of Ruan for a Chinese audience. However, the wealth of historical clips and documentary footage resulted in an unintentional postmodern production that appeals on an international scale.

The film’s marketing works to target a Chinese feelings of nostalgia for the past, and consequently targets a global audience through the image of a significant female protagonist. Much can be read from the film original poster that was advertised in China and Hong Kong. In the poster, Maggie Cheung as Ruan poses in a doorframe, pensively looking at the outside world. Her make-up, dress, and the blurry visual quality of the image all work to suggest an image of the past. The poster has an overall quality that is reminiscent to a vintage photograph. This draws on the nostalgic feeling of a potential Chinese audience, who would immediately recognize the iconic image of Ruan. Her position in the doorframe and pensive expression work can be read as the films claim to reveal an inside look inside Ruan’s personal life, and her emotional battles before her death. Three biographies have been published on Ruan’s life, and there is clearly a large interest in the life of China’s beloved actress and her tragic death. Visually, the poster claims to unveil the mystery of personal Ruan’s life. The film clearly targets an audience who is familiar with Ruan’s legacy. Yet by creating a picture around a successful progressive actress for her time, the film coincidentally attracts a global audience. As the image of the past is used in the Chinese viewer, the female centrality of the film draws in those foreign to China’s popular culture and history. In the 1990’s in china, lifestyle magazines began to promote new images of educated and elegant career women. This transition parallels the exponential growth of female power in the workplace, media, and politics in other parts of the world. Particularly the United States, which dominates global media. The use of a successful and legendary female icon consequentially contributes to its potential appeal on an international film market.

The film seeks both a Chinese and international audience; it plays upon the nostalgia of Ruan’s place in Chinese history, and tells the story through a postmodern lense, contributing to its international appeal. The film was received well both domestically and internationally, as shown in various film festivals and reviews. The film won five domestic awards at the 1993 Hong Kong Film Awards for Best Actress, Cinematography, Art Direction, Original Film Score, and Original Film Song. It also succeeded critically on an international level at the Berlin International Film Festival, Chicago International Film festival, and received a wealth of appraisals from foreign critics. In Reader (Chicaco, III), a reviewer describes the film as “A masterpiece by Stanley Kwan, the greatest Hong Kong Film I’ve seen” (Rosenbaum 1). He describes the triply juxtaposed mode of storytellling, a postmodern feature, to be particuarly enthralling experience. Its postmodern qualities are recognized by other international critics. Film reviewer Tod Booth praises the film by stating “More than just a gorgeous recreation, [Center Stage] collapses time as the actors step out of their roles to talk about them, or watch filmed interviews with the now elderly actors that they are portraying. The film evokes a profound web of resonances as it explores Ruan’s life and art, and the complex ways that film dissolves the line between life and art, time and space, past and present” (Booth 2014). It is similarly praised by the Toronto Film Festival, the Rotterdam Film Festival, and the San Fransisco International Film Festival. Although Kwan’s film is culturally specific, the tragedy of Ruan’s life is intriguing to any viewer. The films works through three different methods of storytelling to play on the historical memories of the Chinese viewer, and inform the likely unfamiliar international viewer. Kwan is strategic in his use of the postmodern aesthetic, as the documentary and historical clips answer the questions an international audience may ask, and provide and cultural context that is lost in other, typically older, Hong Kong films. “Center Stage” works as an example that nationally specific films can be interesting to a foreign viewer and successful on a global scale. Although the film is in Cantonese, revolves around an specifically Chinese icon within a explicitly Chinese setting, cultural specificity does not deny film the ability to be appealing to other cultures.

Through the figure of Ruan, the film tells a story that is relevant to every culture. It’s review from the London Film Festival finds the film to be successful not for its postmodernist techniques, but its human sentiment that is cross cultural. Maggie Cheung’s performance, although in Cantonese, it is deeply moving allowing it to transcend language barriers. It writes, “[Maggie Cheung] is nevertheless doubly moving because she reminds us that despair can hide behind a smiling face”(London Film Festival, 1). Kwan’s film is an example that nationalistic cinema can also dually exist as world cinema. The film gives a Chinese audience insight and stability to its current cultural identity by exploring its past. To a foreign audience, the film presents an image of Hong Kong’s current identity. The self reflexive moments of Maggie Cheung’s interview reveal the relevant state of current Hong Kong cinema and popular culture. The film does not just merely historicize the past, but the present as well through its postmodern form.

1 note

·

View note

Text

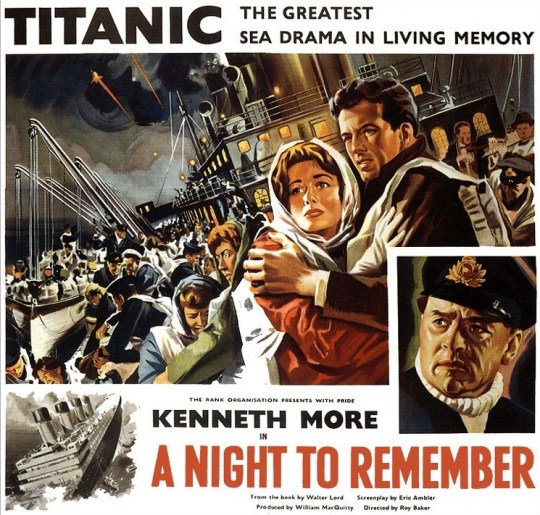

Challenging the Female Threat in Post-War Britain

With the end of World War Two, Great Britain began to see a shift in gender roles with the rising numbers of females entering the workplace. While this societal change was economically beneficial for the people, it introduced a threat to the male population. The films produced in this time can be viewed as a response to counter this growing threat of female power. Roy Ward Baker’s film, A Night to Remember (1958), expresses this in the moments of the ships sinking, as the female survivors are pictured looking onto the disaster from their position in the lifeboats. Represented in the shots of the lifeboats, the female gaze in A Night to Remember is ultimately a product of the male gaze, which projects the phantasy of the subordinate female onto the women in the film.

In her essay “Narrative Cinema and Visual Pleasure”, Laura Mulvey contends that in cinema, the female is viewed through the controlling male gaze. Male audience members will therefore align their gaze will the active male protagonist, who views the female as passive and subordinate to him. In Baker’s film, the male viewer will identify with the male protagonist that is portrayed as the ego ideal, Lightoller, “as the spectator identifies with the main male protagonist, he projects his look on to that of his like, his screen surrogate” (Mulvey 11). Lightoller is the most identifiable character within the film, as the middle class hero. During the climactic scenes of disaster, Lightoller takes on the role as the active male as he organizes lifeboats, and directs other survivors to balance on a capsized lifeboat. His character emphasizes the ideal male qualities such as resourcefulness and strategic thinking. The shot of the females in the lifeboats thus reflect his sympathetic gaze for them, viewing them as helpless mothers and wives. In these shots, the male gaze is “projecting fantasy onto the female form which is styled accordingly” (10). For the male spectator, who is aligning his gaze with Lightollers, the women in the lifeboat appear as passive figures needing to be rescued. Much like damsels in distress, the women watch the Titantic sink with fear in their expressions, and often times clutching their children. The women of the film inspire the male to act as a hero, and to adopt the admirable characteristics of Lightoller. In the shots of these women, the male gaze is not imposing sexuality onto them, but is rather imposing the preferred role for women at the time to remain obedient and nurturing caretakers.

As Molly Brown and the other women of the lifeboat gaze up at the disaster, the female spectator watches this through the male gaze. Molly’s exclamation, “Look! Oh look!”, reinforces the passive role of females in times of disaster which is ultimately, to act as the mother. When Molly suggests that the boat of women attempt to take action and search for survivors, she is quieted based on the logic and reasoning of the male boatman. These females are framed in an unmoving space, merely observing the action from afar. The frantic shots of chaos and panic on the Titanic is contrasted by the static shots of the women, and “her visual presence tends to work against the development of a story line, to freeze the flow of action” (11). Unlike Lightoller, the women of the lifeboat are presented as useless in times of disaster. These shots are constructed by the male gaze, that is visually signifying the passive role of females. The female spectator is thus forced to watch herself through the male gaze, which encourages that their role in society is the obedient wife, and nurturing mother. These shots act as a reminder to the British audience of the 1950’s that gender roles are necessary, and female subordinance is vital for survival.

In these brief moments of the film, where the women of the lifeboats watch as the Titanic sinks, they act as the subject of the male phantasy and reinforce the male as the active figure in British society. As well, these shots encourage the female viewer to act as a passive observer of action. This film reminds its British audience that while women may be entering the workforce, their role remains ultimately as the subordinate wife or mother. It is an attempt to reinstate the gender roles of the past, and therefore reinstate male power.

0 notes

Text

Stagecoach as the Grand Narrative of the Western Genre

John Ford’s first sound western film, Stagecoach (1939) began his career as an iconic auteur definitive of American cinema. It was praised upon its release, but the momentum of critical appraisal increased throughout the 20th century, and the film is now revered as a classic. This early film of Ford’s has come to define his own film career, as well as the American Western genre. There are numerous critiques and appraisals of this film that discuss the film’s iconography. Among their discussions, as they hold similar or oppositional criticisms, each critic agrees that Stagecoach has greatly contributed to creation of the stable western genre. Film scholar André Bazin has noted in his writing: “Stagecoach (1939) is the ideal example of the maturity of a style brought to classical perfection. John Ford struck the ideal balance between social myth, historical reconstruction, psychological truth, and the traditional theme of the western mise en scène” (149). Bazin sees that Stagecoach encompasses the distinctive themes, tropes, and motifs that have come to define the western genre today. He makes no specific mention of the films artistry or intellectual achievements, but contends that Stagecoach is significant for its irrefutable impact on the formation of the genre. This essay will discuss the various writings of critics who similarly argue that the themes and tropes of Ford’s Stagecoach have become engrained in the western genre. Particularly, there is considerable mention of the film’s visual signifiers and musical signifiers of the west, the introduction of archetypal characters, and its ability to communicate relevant American social issues.

In just the opening moments of the film, Ford introduces the visual and musical signifiers that have come define the genre. The opening credits play over the the army troops riding through the scenic image of a dessert landscape, followed by images of natives on horseback. In Jeremy Agnew’s writing The Old West in Fact and Film: History Versus Hollywood he posits that Stagecoach is remembered for its visual imagery of Monument Valley. Although the majority was filmed on set in Los Angeles, its brief images of the desolate valley are remembered. Ford realized the potential in this landscape early on, when he was approached by a local farmer who pitched the location to him and “Ford went on to film six more westerns in Monument Valley, which helped to confirm the images of this scene as ‘The West’” (Agney 88). This iconic image depicts three rock formations was used so frequently by Ford, that it now often appears in the background of other movies and has become known as ‘Hollywood Boulevard’ (90). Since its initial appearance, Monument Valley has been used regularly for movies, television commercial, and advertisements, as the recognizable scene has become one of the most dominant visual signifiers of the west. Bandy and Stoehr in Ride, Boldly Ride:The Evolution of the American Western relate in an interview with Ford in 1964 who stated “I think you can say that the real star of my Westerns has always been the land.. My favourite location is Monument Valley... it has riders, mountains, plains, desert, everything land can offer. I feel at peace there. I have been all over the world but I consider this the most complete, beautiful, and peaceful place on earth” (Bandy and Stoehr 95). It is clear why Ford appreciated the landscape so much, there are reasons beyond Ford’s personal aesthetic attraction to the land that have caused its success as the primary image of a Western landscape. Bandy and Stoehr suggest that Monument Valley “provides a seemingly eternal canvas against which the variables and vagaries of human existence can be etched. Many a classic Western film depends on its capacity to create the illusion of spatial and temporal passage, a passage that is emblematic of the wider notion of the transience of human life” (95). The reasons behind Monument Valley’s success is the deeper meanings that is represents; through a brief image of a stagecoach making its way through a dirt road in a vast and intimidating landscape, a viewer can appreciate the American spirit for success and expansionism. Bandy and Stoehr also reveal that the distinctly American musical score is also evocative of American nationalism. The score of the film by Richard Hageman, was adapted from American folk tunes of the late 19th century, which are simple and familiar. In Stagecoach, the music is nostalgic of the developmental period of America’s past and “provides an almost subconscious connection with America’s past while also affording an upbeat accompaniment to the journey of the stagecoach passengers” (95). The score also appears within the first moments of the film that picture Monument Valley, thus making image and sound of the west inseparable and forever engrained in the audiences mind. In these first moments which combine American folk music with the expansive dessert, Ford creates the key visual and musical signifiers of the genre. It is these classical qualities, which are rooted in American history, that are echoed and repeated in many later westerns.

With Stagecoach, Ford introduces and popularizes archetypal characters that reflect the varying social classes of the nation. In Stagecoach to Tombstone: The Filmgoers’ Guide to the Great Western by Howard Hughes, he discusses the two different social groups that Ford creates within the film: “The stagecoach passengers split into two groups: the ‘respectable’ and the ‘disreputable” (Hughes 6). He distinguishes the respectable characters as Peacock, Mrs Mallory, Hatfield, and Gatewood. Ford then uses the characters of outlaw Ringo, prostitute Dallas, and drunkard Doc Boone, as the disreputable counterparts. Hughes also notes that many other characters in American westerns are modeled after these archetypes, as they perfectly embody different social positions and represent familiar characters that are drawn directly from dime novels and pulp fiction (Hine and Faragher 509) . In this way, the relationship between these characters act as a microcosm of relationships between the social classes of the larger nation. In My Darling Clementine, the character Doc Holliday resembles the Hatfield the gambler, “Doc is one of the night, dressed in black he is an alcoholic” (8). Yet perhaps the most iconic figure that Ford created was with John Wayne as Ringo Kid. Hughes states that the “introduction of Ringo, as he waylays the stage, became a classic western moment. A rifle shot stops the stage horses in the track, while Ford zooms in on Wayne shouting “Hold it!”, twirling his Winchester with its outsized loading lever, in a could of dust” (6). As the morally questionable good-guy, an outcast of society, and skilled with a gun, Ringo Kid becomes the American ego-ideal. In fact, in Germany, the film was released with the title as Ringo, emphasizing John Wayne’s character as the center of the narrative. It is this revenge seeking yet heroic figure that John Wayne so famously played, that has consistently reappeared throughout western narratives. With this colourful cast of characters, Ford creates fixed representations of social groups for the genre. In Fifty Key American Films, White and Haenni review Ford’s representation of Native Americans as a “constantly implied threat but almost faceless and allowed no opportunity to state their case in a context where they were often treated shamefully” (White and Haenni 64). Similarly Eckstain and Lehman agree that the Apaches are deprived of words, as they are only either completely silent, or savagely yelling as the violent opposition from the landscape (Eckstein and Lehman 172). This limited representation set the standard for depiction of aboriginals in American cinema. Women are presented as similarly limited stereotypes; Mrs. Mallory fits the role of the mother, while Dallas is the typical whore. The characters of Stagecoach set the standard for character types of the western, as their contrasting and varying personality types create the perfect on-screen tension that is perhaps reflective of a tension between social classes in America.

The characteristics that Ford uses with Stagecoach have become permanent tropes of the Western genre as a result of their innate connection to core American values. Particularly, America’s Christian values are reflected in Ford’s western: “Based on Christian forgiveness, love, and tolerance, these values are brought into open conflict with racial and sexual difference constructed in binary terms” (172). The film also invites viewers to critique how the disreputable characters are treated by by the respectable characters. James Roman argues that “Ford has woven a morality tale into the narrative: those characters who have postured with airs are depicted as superficial, while those os substance and ‘grit’ suffer the disgrace of their peers” (Roman 32), thus earning the audiences respect. These characters are clearly mistreated and this prejudice is presented as immoral, however the two outlaws are still sent to live as outcasts separate from he rest of society. Similar to the popular belief of those who act against the values of Christianity in American society, they should be forgiven for their sins, yet also be kept far from the upstanding members of society. The music, characters, and themes of Stagecoach collectively work to project a distinct American national identity “with one foot planted in U.S history and the other in American mythology. This symbiosis of fact and legend is the very essence of the film’s enduring appeal and its tremendous influence on the regenerate A-Western form” (Grant 42). After the slow decline of the genre’s popularity, it again rose near the end of the 20th century. Hine and Farhager argue that this turn back to the genre was due to the Western’s ability to critique contemporary social tensions of American culture” (Hine and Farhager 509). The genre has uses beyond entertainment, and has come to act as a mode of representation for relevant issues surrounding nationhood and social status. The clear narrative structure that Ford uses, has also become the standard for the western narrative, using a “three act structure that is marked by events and shifts in a geographical setting” (Premaggiore and Wallis 41). This same structure, is used repeatedly throughout the genre, retelling similar stories. Yet the genre remains successful due to its ability to discuss culturally relevant tensions. The formulaic competition of of Ford’s western narrative is timeless, as it deals with universal issues of class conflict and racism.

Ford’s iconic film is considered important by film scholars, not particularly for its cinematic artistry, but for having made a permanent mark on American film history, and perhaps American ideology as well. With one film, Ford is able to create distinct visual and musical signs that are now inseparable from the genre. The diverse cast of characters in Stagecoach have reappeared time and time again, varying slightly, but always reflective of certain social classes. The tensions that arise from these character’s differences are representative of different social issues in America that arise throughout history. The film has been discussed since its initial release in 1939, but has gained recognition increasingly throughout the years. It is now recognized for its introduction of dominant western tropes that have come to signify America as the West that is is known as today. Stagecoach’s impact reaches far beyond its popularity and critical appraisal, but has become the grand narrative of the western genre.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Across the Niger: Authenticity and Internationality

West African film is not defined as a particular genre, like perhaps the Western or Film Noir is as considered by critics. These genre’s have particular notable aesthetics that are consistently reused as an act of fidelity to the artistic goals of the movement itself. West African film can be understood more simply as National Cinema. With this understanding in mind, it is much more difficult to discern whether a film ascribes to a particular aesthetic, and if this maintaining this aesthetic is even necessary to define a film as West African. This essay will discuss the elements of Ojukwu’s Across the Niger (2004) that are distinctly and intentionally part of the West-African aesthetic, the aspects that diverge from Nigerian culture to be globally appealing, and resolve that Nollywood films are capable of being both authentic and international. Across the Niger can be used as an example of Nollywood’s flourishing film industry that is capable of success beyond Nigeria’s boarders, while also maintaining an aesthetic that is culturally specific to Nollywood.

The lack of funds available for production heavily influences Nollywood film’s aesthetic elements. This lack subsequently results in unintentional affects such as outdoor lighting and realistic settings. However, there are many aesthetics of Nollywood films that appear unintentional but have been critically and thoughtfully planned. In her work “Storytelling in Contemporary African Fiction Film and Video”, Dovey navigates through these aesthetics to determine which are formed unintentionally and which are developed through artistic thought. It is discussed in Dovey’s argument that the long takes, which are a signature of Nollywood editing, is an unintentional element. Many takes are elongated to ensure that the film lasts the length of a bus journey, or to delay the narrative in order to create sequels (Dovey 97). Although this editing staple may be unintentional, it has come to create a recognizable Nollywood aesthetic. Conversely, The themes of the films are intentionally focussed on themes of relatable social issues like legacy and inheritance, husband snatching, prejudice, and child abandonment, all set within a local context. Across the Niger demonstrates many of the “local aesthetics” that have come to define West African Cinema. This film diverges from Western standards of what should be presented in West African film; the film does not center around colonialism, though effects of colonialism are inevitably present, and does not feature the same issues that European financed Nollywood films do, such as HIV/AIDS, poverty, discrimination, or children on the street. (Okome 31). In the case of Across the Niger, the social issues and themes of Habiba and Dudems’s relationship are told through a journey that is set in the specific context of the Nigerian civil war between 1967-1970. Critics of Nollywood will often downplay the artistry of films, reducing them to amateur and overly dramatic works. However, Dovey contends that this dramatism is much more intentional than it appears. When thinking about film’s relation to Nigerian oral storytelling, “a particular kind of adaptation and visualization of oral and spoken narratives is thus at work in the video films” (Dovey 96). Nollywood films must not only be read in relation to “reality”, but must be acknowledged as a cultural transformation of story telling. Thus, the blatant dialogue and dramatic acting can be seen as a result of this transformation of West African oral storytelling into the film medium, and not merely as a cinema lacking in artistic thought. The editing is also more thoughtful than it may seem to those viewers accustomed to Hollywood films. Nollywood gives preference to wide and long rather than close ups, unless during a particularly emotional scene. The film’s use of editing is consistent with the majority of Nollywood films; most scenes are a compilation of long shots, with the exception of highly emotional scenes. When Habiba expresses emotional depth, close ups of her crying face fill the screen. This occurs twice - first when she tells Dudem to let her leave his village, and again during the film’s climax after Dudem is shot and she expresses that her love is “full like a river”. Nollywood also favours minimal editing and scenes that enhance the emotion through visual and aural effects. These techniques are thoughtfully used to tell the story in the most emotive way. Across the Niger exemplifies this style of storytelling through Habiba, Dubem, and Nneke’s complicated relationship. The drama and obviousness of the narrative can be seen in the scene in which Nneke attempts to seduce Dubem. In an alternative Hollywood rendition of this scene, Nneke’s motives might be more ambiguous. Yet in the film, Nneke’s motives are made clear by King Igwe’s advisor, who repeatedly tells her she must make Dubem fall in love with her by sleeping with him. This allows for the audience to understand the story without any confusion or ambiguity, much like the way traditional oral stories are narrated.

Across the Niger tells an authentic story through Nollywood techniques, while also subtly catering to a foreign audience. Ojukwu’s decision to film in the English language can be read as a small choice directors can make which allows their film to be potentially internationally successful. In his writing “Postcolonial Artists and Global Aesthetics”, Adesokan states, “most of the Nollywood films that circulate globally are in English and rely on standard generic conventions, even though, as the UNESCO figures show, more than half (56%) of Nollywood releases are in Nigeria’s three major local languages” (Adesokan 83). It is clear by this statistic that films that choose to use English, like Across the Niger, are allowing their film to be appreciated globally at the risk of being less culturally authentic. It could be argued that this film is less Nigerian due to its English language, and relinquishes its cultural specificity in order to cater to a global audience. However, the use of the English language does not affect the films local popularity, as “English language Nollywood films resemble television soap operas in Formal Terms, and travel better among Africans” (84). What may affect Across the Niger’s cultural authenticity is its apparent lack of African spiritual beliefs within the tribes culture. Andrew Rice notes the importance of these beliefs, “Nollywood movies, both old and new, often play on traditional African beliefs about magic and spirits” (Rice 1). Conversely, Across the Niger does not focus on spirituality, rather it replaces spirituality by focussing heavily on tradition and politics between tribes and families. The reason for this omittance could perhaps be explained by the desire for this film to be accepted by a foreign audience who may hold different beliefs. The stories in “Nigerian films with strong doses of the occult (or ‘black magic’) have had a particular hold on the popular imagination. These occult forces are banished in the narratives of many of the films via the Pentecostal Christian practices in scenes that are often a source of amusement for secularized, Western audiences...it is harnessed to a project of a Westernized system of commodity consumption” (Dovey 93). The lack of spiritual theme’s in Ojukwu’s film is not a commonality among Nollywood films, and reveals the desire to appeal to foreign audiences and also project a representation of modernizing Nigeria.

Across the Niger utilizes the aesthetic principles that have come to create the formula for as successful Nollywood film, yet the film is still understandable to a foreign audience. Many specific elements of the nation’s history and culture may loose their significant to a foreign viewer, but the human elements of romance, prejudice, love and sacrifice can be equally relatable to any viewer. The film is definitively West African and adheres to a very specific local aesthetic. However, the film is also able to reach beyond its Nigerian boarders and be relevant globally. Nollywood films are successful in St. Lucia, and trade to the Middle East, Hong Kong, United States and South Africa and the United Kingdom (Dovey 102). Unfortunately, the aesthetic elements of Nollywood are perceived as “awful, marred by slapdash production, melodramatic acting and ludicrous plots” (Rice 1). Okome notes that Nollywood is constantly criticized for “lacking depth, artistic and technical quality” (Okome 33). However, despite its lack of technical success, I found the films narrative and particularly Habiba’s struggle with love and discrimination to be particularly moving. In this sense, the film is full of narrative depth, and one cannot denounce its artistic elements. Despite the low budget effects, unrealistic battle and melodramatic acting, the film is still capable of evoking a high degree of emotion in a non-Nigerian viewer.

In conclusion, through the analysis of Across the Niger, it can be seen that Nollywood cinema has a specific framework of aesthetic principals that are intentional in their effects. It can also be seen through this film that subtle choices are made in order to cater to an international audience. Although the film is able to appeal to foreign audiences and strays from some of the typical tropes of Nollywood films, it is distinctively representative of West Africa and only West Africa, proving that a film need not reject all foreign influence in order to be authentically national.

1 note

·

View note