Text

On the Wild.

In the beginning, there was nothing. Then a single creative spark made something out of nothing, borrowing the best of many worlds, and before long came the Wild. First a whole world, conventional in rules and mundane in contents, it had at some mysterious and indistinct point suffered a calamity so profound it shattered the world into teeny-tiny pieces, and tossed them left and right, up and down, across time and space. Now, it is a world divided; split into a thousand island and one, and maybe even more, where creatures of all kinds make a do, yourself among them.

Enter the Wild. Befriend it, respect its law, and it will in return be kind and favourable to all your ventures. To go against the Wild, and disrespect the law, is to play a game of chess with powers great and unpredictable. Or so say the soothsayers and prophets and far-seers, and other outspoken folk. But the problem still stands: The Wild allures adventurers and explorers from anywhere and of every disposition. They board the airships and aim to cross the gaping chasms between the isles in search for parts unknown, and in so doing challenge the Wild to a battle of luck.

Why do we hear the call of the Wild? Why it beckons us, when it is the Wild that employs mysterious ways to consume much-too-curious travellers? Perhaps you will be the first to find out. Your airship, *The Unyielding*, awaits only the order to embark. Until it does, however, I’d advise any aspiring explorer, even so eager as yourself, to educate themselves on the Wild matters.

Matter 1: The Cosmology

A world without rules is a world much too arbitrary. The Wild, thank goodness, rests on a foundation solid in structure and clear in law (though not devoid of Lovecraftian instability, something we will touch on in due time). Binding all that exists within the Wild is an omnipresent gas -- the zephyr. Scentless and weightless, zephyr is what our earthly person would call the air, save for a few un-oxygenic properties it has that the air we breathe on Earth does not.

Zephyr is safe to breathe in reasonable quantities, which themselves are relative to the species in question. Some may breathe more of it than others, but what stays true for all is that, sooner or later (most often sooner), the creature gobbling up too much zephyr will experience what is called the Wild-headedness. The foul gas will cloud their judgement, and warp their mind over the course of days so much as to drive them bonkers. Indeed, it is not uncommon to see explorers return disturbed, whispering to themselves some cryptic nonsense, and it is then said of them that they’re Wild-touched, and as one would presume, no Wild-touched traveller has to date ever recovered from the mind-twisting touch.

But, there are lands safe from the zephyr; pieces of land large enough to have developed an “atmosphere,” and ousted the lion’s share of that cosmic poison. Such lands are quick to nurture prosperous civilisations as more and more nomads are drawn to zephyrless refuge. It is as such unfortunate that few floatlands may brag about their atmosphere; in fact one is twice as likely to encounter a land engulfed in the zephyrous miasma. At times even, unbeknownst to the unsuspecting traveller, what might strike them as an airful land, is in truth a land with an atmosphere too thin to banish all of zephyr, and so there it flies unrestricted, sucking in quiet at the unaware guest’s sanity, until they too find themselves forever Wild-touched.

Zephyr also appears to attract, or even conjure, especially horrid weather. Whereas upon the floatlands it tends to be stable of mood -- one day mildly temperate and on another temperately harsh -- Mother Nature likes to throw a temper tantrum whenever her children attempt to sail the zephyrous space. Thunders strike aplenty from within the clouds, and wherever they can reach; powerful currents toss the feeble airships caught within them around like feathers, and the dreaded whirlwinds (although rare) may send even the strongest of vessels flying leagues away from where they were headed.

This area of the Wild, by far the most abundant, and sandwiched between land and other celestial bodies, came to be known as the Betwixt. One can not leave for a different isle without also crossing the Betwixt along the way. The act itself earned a colloquialism, “to fly betwixt.” Whenever one flies betwixt, they embark on a journey across this chasm to a neighbouring isle, taking on a tremendous risk to their life and sanity.

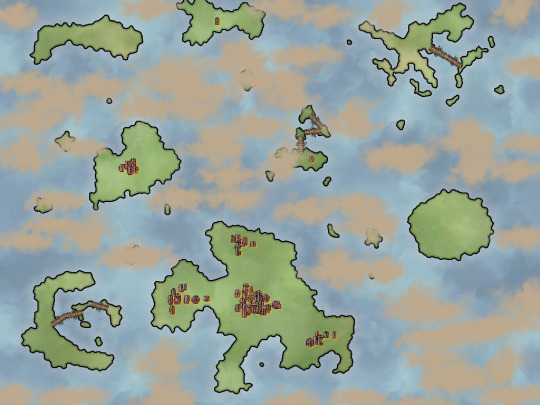

If we were to project the Wild on to a map; to look at the world from a bird’s perspective, we would see a clear pattern emerge to the way celestial bodies are situated. Between them are the poisonous clouds, always there and slow to madden (but sure to do so), that the Wild folks termed Betwixt:

Notice how zephyrous clouds have engulfed the smaller lands, whereas the bigger catch remains predominantly unscathed.

The Betwixt may be your best friend, or the worst enemy. It is never clear what your relationship is to be whenever you take off into the Wild, but the Betwixt is kind enough to make it apparent when comes the right moment, either with a smooth sail to your destination, or a spontaneous whirlwind until the last moment hidden inside a zephyrous nebula. On that note: pirates, marauders, and lawbreakers may find the thick shroud of a nebula, rich in zephyr, to be a wonderful hideout few orderlies would have the courage to investigate.

Zephyred isles often provide a secluded base of operations for many mages, mancers of various schools, and physicians dabbling in unorthodox fields of study. Remote, fraught with traitorous weather and poisonous amounts of zephyr, they are often left well alone, and probably for good reasons, too.

To call upon the Betwixt to deliver you from misfortune, or challenge it to a battle of luck whilst flying, is a decision you will have to make as a player. The Betwixt is as much a tool in your arsenal as it is space for you to traverse. Still, I’d advise all sailors to keep their wits about them, never you may know when your favour with the Betwixt will run out.

2nd Matter: The Semantics

People of the Wild have never known the fluctuous oceans and salted seas, as there no longer exists land big enough to hold them. This fact of life ensured that languages and cultures of the Wild never developed words to describe outspread bodies of water, the size of oceans and seas, and neither did they arrive at the words derived in part or in full from their relation to the high seas and azure mains, be they islands or archipelagos or other.

The vocabulary we earthlings turn to talking about islands and archipelagos makes little sense to wildlings. They would understand what the “land“ of an island means, but the rest would leave them befuddled. Islands and archipelagos, in particular, are terms one has to rule out for a floating world for etymological reasons. Both words, if you were to trace them all the way back to their forefathers in PIE, happen to be portmanteaus of Indo-European for “river” (proposedly) -- that which is swift -- and Indo-European for “land.“ Therefore "island” describes a piece of land rested on a body of water, which would in theory be a possible but unlikely semantic development in an environment washed at most by small rivers and lakes. Many (if not most) of Wild-born peoples would simply never come across an island anywhere in their homeland, and thus never coin the relevant term; land surrounded by water would stay the stuff of contemporary science fiction.

Since the concept of islands and the relevant word have never been coined, peoples transcending the boundaries of their homeland do not think of the land they discover flying betwixt as islands. Anything but! Instead, they would size up the newfound land (wink-wink Canadians) and term it according to scale:

Lands comparable to or greater than their own, vast and bountiful, would be judged as Greatlands.

Lands smaller, only a little or downright minute, would be recorded as Minorlands.

Most peoples distinguish between great- and minor-lands. While these are not the words they would speak in their native tongues, translated into English they best convey the semantic and conceptual process that went into and evolved the words they use to describe the lands encountered on travels across the Betwixt. To them, it would not make sense to classify the lands as islands, for “island“ as a word implies land upon water -- literally speaking -- something wildlings wouldn’t think possible.

This same line of thinking I try to apply to all the other terms native to our world yet unfounded in the Wild, and supplant them with terms both clear to us and grounded in the semantic development one would expect from a floating world, and “floating” cultures. The choice of words they make reflects the world around them, and the traits unique to its cosmology. I have to stress, though, that I’m by no means a wise-headed scholar of all humanitarian and applied disciplines alike; I’m just a hobbyist, and the neologisms I invent for the Wild are altogether speculative, and nothing more.

3rd Matter: The Floating Lands

Second in number to zephyrous clouds are the floatlands, stretching as far as the eye can see, maybe even till the very edge of the observable world. Strip the Wild of the lands, and you would render it somewhat of a desolace, sparsely dotted with an occasional nebula, shining star, or the dreaded whirlwind, stashed away someplace on the outskirts to catch oblivious explorers off guard. It is upon these pieces of land torn away from long lost planets (or the great supercontinent, or the Primordial Star, depending on what you take to be the authentic Creation Myth, for there are plenty), that the Wild’s vast majority of earth-like features unfold.

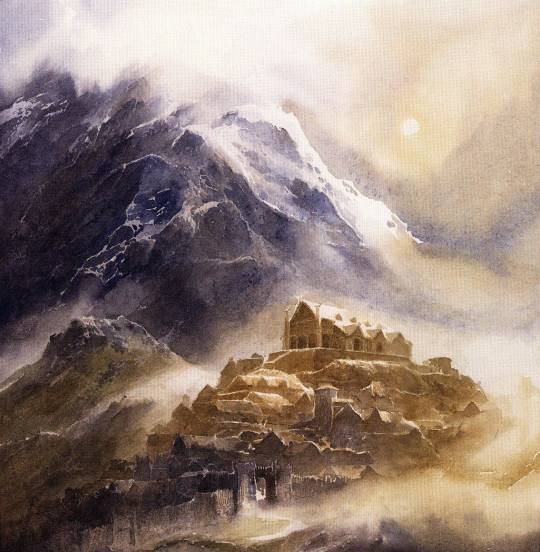

Greatlands, true to their name, happen to be the greatest in extent. They stand as the most diverse in nature and features, owing to their scale; it is not out of character for a greatland to offer a dozen different habitats for the inquisitive traveller to discover. They hoard flora and fauna that would be a curiosity to stumble upon travelling a minorland, and the magnificent mountain ranges are but an ordinary fact of life, originating from the time that there were not great lands, but one too many minorlands drifting too close to one another.

The clash, in time, erected mountains recognised in the modern age as the peaky landmarks of a great many greatlands. Rivers and lakes wash them, and many species one is to encounter throughout the Wild claim descent from one such land or the other, cementing the popular opinion among wildling scholars of greatlands as the undisputed cradle of civilisation.

Minorlands, by contrast, are the smallest of lands, and as such very homogeneous in nature and terrain. Many a time they host temperate uplands, whether defined by scorching dunes or grassy hills or bone-chilling piles of snow, and seldom have another biome. Guesting adventurers are forced to walk the same plain time and again, hoping for a path somewhere that is not a desert with no end or an ever-stretching meadow.

Yet, minorlands are famed as the best places of seclusion: farmsteads have since time immemorial bonded with these flattened blobs of dirt and thickets, their predictable weather and absence of unwarranted surprises be praised; shady sorts, too, find the safety of a remote minorland to their liking, and so do polities on the rise, erecting watchtowers upon them to spot unwanted intruders from afar. Rural and tame, predictably temperate and never at all hiding dangerous surprises, they for certain hold a slew of advantages over their great towering counterparts.

Chainlands are less so a shape or form of a land in the Wild, and more so a cluster of the two varieties aforementioned. Ages ago, the first peoples would without question have entitled them minor- and great-lands alike, but the passage of time led them to invent and construct bridges and passes to connect these lands together, in an effort to make travel much less of a burden.

Of stone, of wood, or spectral essence (born of powerful spells), bridges to a chainland are as veins to a human -- cut them down, and the chainland will be sure to suffer a fatal blow to the economy and infrastructure. This reliance on bridge-making, and bridge-keeping, had implored the Wild folk to derive a neologism to describe this network of land and bridge. The Chainlands, the lands chained one to another.

Greatlands among chainlands are few and far between, but when they are, they only ever bind the neighbouring minorlands to drift around them, like moons round a planet in our world. The pull at times is so strong that the bound minorlands break apart, forming together a ring of shredded land, themselves at times entitled the shredlands.

Minorlands, on the other hand, stand unbeaten as the most usual finds in any given chainland, and more often than not the only land there is to be seen. When it is so, and there is no greatland to project authority upon the minorlands, they tend to revolve around each other, their pull so weak that the revolution appears paused to all but the most perceptive and patient of eyes.

The rarest of all is a chainland wherein two greatlands do battle. Under that circumstance, the two colossi fight for dominance over the chainland, and in due time (lasting millennia, and longer still) the pull they exert upon one another will tear them to pieces that the future wildlings will take for minorlands. It is believed all chainlands had in the forgotten days been greatlands dueling to death, and the minorlands as a phenomenon had only emerged from the rubble the duel had left. This is however in the view of many a contradiction to the theory of minorlands as the forefathers of greatlands. Sweet, one more thing to argue about...

4th Matter: The Phenomena

Rarer even than two greatlands locked in an ageless stalemate are the naturally occurring phenomena a keen explorer is sure to come upon at some point in their chasm-crossing career. They range in scale, and use, and animosity to the beings caught in their vicinity, but all are united in the danger they pose to every living thing, sentient or otherwise. They toss, and poison, and twist the minds of their unlucky victims, and beware they who dare venture someplace never charted.

Luckily for the Wild folk, all but one known phenomena are stationary; it would take a great deal of law-breaking and space-bending power to set them in motion -- more still to make a weapon out of them -- and the very idea has become the subject of Deluge Myths among many Wild-born faiths and traditions.

Note that the list I offer down below is incomplete; it would take me too much time, too many letters, and even more brainpower to scribble all of the wild ideas I’ve come to cooking up a host of obstacles for the Player to overcome on their journey across the Betwixt. I will instead list the ones I’ve thought about the longest, ordered least to most interesting, and leave the rest for another time:

Nebulas

Native to the far corners of the Betwixt, miles upon miles away from the closest floatland, nebulae take shape when the zephyrous currents, flowing of their own accord through the Betwixt, or given a violent push from a whirlwind, come to a halt in one place, and condense into clouds. The clouds then clash and thicken, and before long turn so dense one would struggle to make out the loosest detail even ten metres ahead, and not one propeller in the Wild would have the horsepower to blow the clouds away.

Naturally, it is as dangerous to sentient life (thanks in no small part to copious amounts of zephyr) as it is useful the mortals seeking refuge or a place to hide. The big problem for them is therefore to puzzle out a way to breathe, but also maintain their clarity of mind. Devices and gear exist to protect the daring pilots, but even they give in under so much stress. Oversaturated air notwithstanding, nebulae have been known to act as naturally fortified hideouts for criminal elements; whole syndicates were fabled to raise floating fortresses amid the nebula, and sometimes they would discover by pure chance “castaway“ minorlands inside.

Few have come back to tell the tale, and so it is to this day a wonder to many; one that raises a plethora of questions, most notably the question of what else could possibly be hiding in the nebula’s heart?

Currents

Driven now by cosmic forces and then by a raging whirlwind, zephyrous currents serve to experienced pilots as motorways serve seasoned drivers here on Earth -- they send even the heaviest merchantmen flying like a lightweight schooner, at the expected cost of abnormal levels of the gas in the air. Currents and lanes are cognate, and the words are used interchangeably to refer to the same phenomenon.

While impossible to influence, to slant or pick up the pace, almost like the current of a river, they always run their course like they did since the beginning of all things. Only whirlwinds may redirect some portion of a current away into the Wild, and the lost current soon stops deep in the Wild and turns to a nebula.

Even then, the main current will get to keep the direction it is flowing, making them a tempting choice of many traders and colonists, who by force of circumstance have to man ships so heavy that the cost of travel is immense. The current step in to help, and take some of the financial edge off.

Currents may every now and again branch out, and the individual branches may converge into another current at the very tip, forming networks vital to the circulation of trade and commerce and people throughout the Wild; about as essential as bridges are to a chainland. Maps charting the currents and the branches are worth their weight in gold, and it is only natural that many explorers make a living mapping the currents they chance upon in their travels.

Whirlwinds

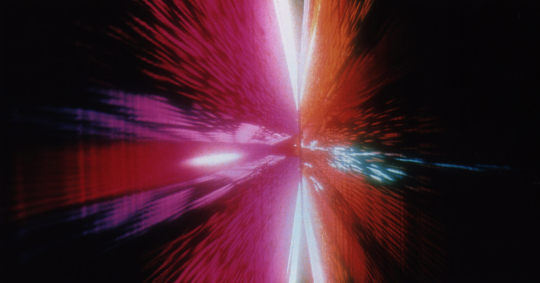

The fear; the nightmare of every sailor seasoned and amateur alike, are the dreaded whirlwinds. Itself a smidgen tear (or hole, a better word) in the fabric of reality, a whirlwind bends the space and time around it with a pull a quintillion times that of the largest greatland conceivable; so strong it stretches all matter too close around the dark epicentre into a bright spiral of heated zephyr, and the chunks of land and other fallen material.

There’s a constant rotation of matter happening within the whirlwind’s ring, as old matter eventually reaches the point of no-return -- the whirlwind’s lightless and lifeless centre -- and new matter takes its place. What happens to the old from that point onwards is a subject shrouded in mystery, with only a handful of scholarly works, all pure speculation, as not one Wild person has ever managed to fly close to the whirlwind and stay whole, let alone fly so close as to observe the matter being absorbed into the black core.

Legend has it, and so does science, that should a whirlwind draw too close to a greatland, it will eat it whole, bones and all, and leave not one trace behind. Thankfully, there have never been cases observed and recorded of such calamities taking place, and gods help us that they do not befall us tomorrow.

Testament to the whirlwinds’ power is their ability to draw from the current a new one, and in so doing lay foundations for new currents for the network, or even the new nebulae. They are not, as such, entirely destructive when examined under creationist light.

There are moony captains out in the Wild who may, equipped the right things, ride on the very edge of a whirlwind’s ring to gain speed one would never reach in the strongest current. Nevertheless, I’d advise you, young captain, never to consider a means of travel with a potential so devastating.

Stars

They go by many names; of their own making and christened so by their mortal worshippers from the floating lands. They prefer to name their kin Celestials, but the noble intention this word carries could not be further from their nature. Aye, the Stars of the Wild are in every way as sentient as the Wild peoples, and just as numerous, but rarely if ever benevolent. Quite the polar opposite.

Stars are power incarnate; their blinding light may scorch and turn the lesser life to smoke and ash, but it may also plant the seeds of life upon a lifeless greatland, should the Star be in the mood to curb the sunlight. The taste of this godlike privilege has driven many of them arrogant of character; reluctant to hear the plights of land-dwelling “insects” they warm, whether by choice or circumstance, and eager instead to bind them to their will.

Lands orbiting a Star, while far more bountiful than the lands lit only by the bleak natural light of the Wild, bask in the Star’s life-giving rays, and enjoy a life of everlasting overindulgence, with a sinister catch. Not so much a catch even, as a figurative leash that the Star has put them on, holding entire civilisations hostage forced to appease it, and many Stars are infamously whimsical.

All too often Star-lit lands resort to Star-worshipping zealotry, too small both in stature and in will to rise against their blinding overlord. Some did, though, and gallivanting bards sing of their ashes gliding through the Wild along the currents, the last traces of a civilisation wiped out in the flash of light...

To approach a Star is, too, an experience thrice as maddening and sickening as spending a minute too long in a nebula. The closer you drift towards them, the louder their diabolical whispers grow in your head, incessant and urging you to turn right around, or perish from your own madness. Spend long enough near a Star, and upon your unlikely return to the mainland, people will speak of you as as the Stargazer; the Star-touched. Needless to say it is an ailment every bit as chronic as the Wild-headedness.

Given this way of things, little is known to scholars from outside the Star-lit lands of the Stars’ origins, or the properties they possess besides the incomprehensible language they speak, and their obvious lust for power. It is only known of their kind that some of it is not as malevolent; the Stars aligned to do good have only been seen once or twice in known history, and few endured the pressure from their less-ethical peers so long as to live into our age. Regardless, maybe the fate will bring you together, young captain, and then you would be the one to teach me of the things you’d learnt from the meeting.

Finita La Commedia

That is all you need to know, for now, young captain, and I hope this minute handbook taught you a concept or two. Now-now, “The Unyielding” is ready, and so are you. Bewildering adventures await deep within the Wild; distant shores, bizarre creatures, and life-threatening phenomena itching to be discovered. Take notes of the things encountered and events witnessed, and maybe your findings will fetch a pretty penny. Don’t you dare approach the Stars, though, I wouldn’t wish upon my apprentice the Star’s pestilent touch. Come back to us safe and sound, friend, and pardon my sentimentality.

We all bid you a very fond farewell.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

On Worlds.

We inhabit them. We've christened ours Earth, but there are some who call Middle-Earth their home. I've heard many dashing tales from the Borderlands, and on all too many occasions guested in Azeroth. All these faraway lands are unique in their own right, sporting flora and fauna so diverse it really does make one wonder how such things came to be, whether out of nothing, or out of the wilds of human imagination.

I've always been under the impression that it would take a person too much blood, sweat and tears to fashion one. But here I stand, alone, and I need a place to set my latest overambitious and never-ending enterprise. It's a habit I'd always detested deep down, but came to respect over time, and now I say it is the prospect of making something grand, chipping away at it day and again, that gives me one more reason (among many, mind you) to get up early in the morning, and wonder what aspect of it am I going to work on next.

So it is, that I've been pondering on the sort of a world I would want you, the Player, to quench your wanderlust, and perhaps take your subconscious somewhere it has never travelled.

My research -- that hunt for inspiration, artistically speaking -- took me to media I have and have never ever witnessed, or heard, or read, or seen. I've browsed art, played this game and that; I've watched film and series, and I've brushed the dust off some of my forlorn literature. I've even dared to show up in the local library for once in an embarrassingly long (by a reader's standards) while, and borrow a "manuscript" or two I thought had a few interesting ideas. But, I have to admit, Stack Exchange remains my personal favourite. There are so many great minds there, with an equal knack for world-building, and even more thought-provoking questions granted inspiring answers. I can't recommend it enough.

On to the point, though, and it is that I've compiled a list of "archetypes" to take into consideration building my own world:

Earth-likes

What a surprise, huh? I believe it to be the most widespread archetype, and it is rather self-explanatory. An Earth-like world is more often than not a carbon copy of the blue planet (or our rather milky galaxy), with oceans and continents shuffled a notch to dodge the cosmic copyright, so to speak. It is again most common, and for a good reason: we know plenty about the science that keeps such worlds (and, by extension, our own) spinning, and the life living the way it does. It is a solid point of reference, backed with facts and studies so easy to look up on the web, or anywhere bookish, and it is always oh so tempting to use.

A few notorious examples taken from modern authors include...

...a continent under the influence of Celtic and Germanic myths; known as Middle-Earth of J. R. R. Tolkien.

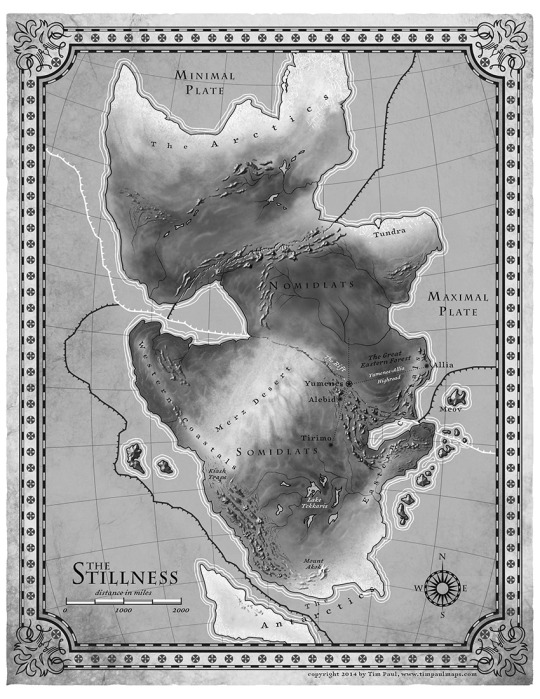

...the super-continent of Stillness by Nora K. Jemisin.

...the Present World, to some extent a mirror of ours, and found in Kentaro Miura's Berserk.

...or the unforgiving deserts of Arrakis, credited to Frank Herbert.

...or Faerun, the iconic setting of Forgotten Realms.

...or even the Journey, courtesy of thatgamecompany, and the dunes one has to slide down rushing to the mountain's peak.

If at least two of the above ring a bell, you may have an idea of what brings all these worlds together, and by extension, what I think constitutes an Earth-like world. If not, then let me illustrate my point instead:

Go on, draw a comparison! It wouldn't take a particularly perceptive eye to notice that even a seemingly outlandish example, the desert planet of Arrakis, shines features not too unlike those we may find here on Earth, albeit "turned up to eleven," for the lack of a better expression. They are planets filled with oceans, and continents in between the oceans, most of them, and in general they follow the same rules we follow in our universe: desert storms rise as the wind blows, plates collide to erect mountains, and sentient life is soon to usher in an age of civilisation. Physics and passage of time progress the world as you would expect them to.

Naturally, there will be a degree of variation between Earth-likes. George Martin's Westeros, for one, is an otherwise conventional continent subject to unconventional seasons, some so abnormal they shape entire cultures -- consider the Long Night, for instance, and the impact it had on the Westerosi folklore.

Let's touch on Arrakis again: it is too an Earth-like world at the core, that suffered from a speculated misfortune of a near-miss encounter with a comet, and what once might have been an arid and bountiful world has now been left a scorching desert inhabited by massive sandworms that have evolved to swim through the sands as though they were oceans, and gobble up the teeny-tiny human wanderers crossing their "soil." A few similar worlds come to mind: Kharak, just as extreme and featured in the Homeworld series, and the much more famous Tatooine, the brainchild of George Lucas.

This big quirk -- extreme weather, unpredictable seasons, or morphed geology, or fictional species -- I prefer to dub "the Twist." It is something, a phenomenon or fact of life, that sets this world apart from ours -- something you can use to suggest that the world at hand is its own, and not Earth put in an alternate reality. Extreme biomes of Arrakis or Kharak, and bizarre seasons of Westeros, are just two examples of the Twist. Magic and magical beings found on Azeroth, or in Faerun, is another.

While the Twist is found in all archetypes, I'm of the opinion that Earth-likes depend on it more than others. Take away the Twist, and you will be left with yet another exoplanet, abiding by the rules we all know and, to be frank, find them too mundane to entertain us, or to leave a lasting memory.

As you'd expect, this was the first archetype I visited and considered for my game. The Twist I wish to feature, to go hand in hand with game mechanics I have devised, is the marriage (or clash, depending on your point of view) of science and magic, and the many ways cultures practicing either-or-both would balance them out, or tip the scales in one's favour if they so desire. I'm also very keen on endangering the Player on their journey, which I want to be perilous, and for it to matter more than the destination. Think of it as a world of vagabonds and gallivants, travelling from one bizarre place to a place twice as otherworldly, and embarking on life-threatening quests.

I've considered several worlds, most notably Kharak -- whose native species, the Kushan, traverse it on trucks and jeeps and other sand-crawling machinery. Cities on that scorched planet exist as only safe havens around, surrounded with lifeless sands, and to make it from one city to another is a dangerous affair indeed. The theme resonated with me quite a bit, but I did not find desert planets a good choice for my game, for many reasons:

It is, as the name suggests, a giant desert. There aren't that many biomes (just two, in fact, if you count largely mechanical cities as one) for the Player to explore, and there is little challenge in generating them on the fly, as opposed to a more varied world.

Throwing in arid biomes we discover in worlds like Middle-Earth or Narnia, or Faerun, felt far too conventional to me, and in my mind there would not be much room for an apocalyptic event so crippling as to make exploring this world nigh fatal.

Even if I dodged the desert altogether and rolled with a different biome or biomes, I'd still have to balance between two problems I doubt are easy to solve: featuring more biodiversity in a fundamentally monolithic environment, or more extremes in an Earth-like world that would not fit in very well.

Banality. Banality was a major concern for me, as there are oh so, so many Earth-likes out there in the industry, and the last thing I wish for my little side project is to offer yet another one. No sir!

Scope was the last but nevertheless just as important. It is difficult to fill up a giant continent, or continentS, with enough quests and points of interest to keep the Player invested. It is hard enough to produce enough scripted content, a la World of Warcraft, and it is harder still to delegate the creative matters to an automaton (Talking about you, Left 4 Dead!). Earth-likes, to my understanding, necessitate imposing scale, that I can not hope to achieve neither alone nor in company.

So I scratched this archetype off my list, and again I went searching every nook and cranny of the game industry and beyond for patterns and clues to make into archetype...

Otherlands

Perhaps not the best title to describe a world so otherworldly as to defy all laws native to our universe, but I nonetheless thought it described what I had in mind for such worlds best. Exotics, Otherlands, Alternate Realities, you name it: they spit on the natural laws we've always known, and turn what we consider to be natural upside down, from a relative point of view (I'd image they'd think we earthlings bend their ideas of what is natural, vice versa). They more often than not have so little in common with a conventional; continental world, that as a Player, you ought to be born anew, in a sense, as you have to come to terms with the new reality, and learn the rules alien to your human brain-box.

While not so abundant in fiction or film, there is an unexpected plethora of otherworldly examples found in video games. I suspect, as little more than a humble writer and not at all a qualified game designer, that the blame (the reason, rather) is at least in part to be pinned on the freedom of mechanics worlds detached from all physical boundaries allow. You're no longer on Earth; seldom even in our universe, and more often in a dimension forged by game designers to fulfill a very blunt purpose: to serve the gameplay, in full. I'd imagine it is times easier to set a game built on mechanics hostile to laws of physics somewhere abstract; mallable, in a way, to the designer's whim.

Thinking of examples took me to these fine pieces of digital entertainment:

William Chyr's Manifold Garden is, to me, a quintessential Otherland. It is set in an abstract world wrapping on itself, juxtaposing impossible geometry against Euclidean space. About the only link to our reality it maintains is the presence of gravity. Look up and down, try interacting with the objects or solving the puzzles, and you will very soon understand this is NOT the realm accomodative of your earthly instincts.

Alice: Madness Returns, too, features an Otherland (not Otherlands, fellow Alice fans!), a level set among the clouds, far above in the sky -- none other than Cardbridge! Playing cards dwell there, and glide along the windy streams to form marvellous paper castles in the sky, and bridges, and gates for Alice to cross on her way to the evil (is she really?) Queen's heartful (quite literally) domain. Like in Manifold Garden, physics still permeates this world, but the only "actor" it appears to affect is Alice herself. All that surrounds her, on the other hand, behaves in a way we would think odd.

Oddly enough, Valve's Ricochet is one more example of an Otherland, the way I see it. It's set in a pitch black void, a pocket dimension of a sort, and constricts its gunslinging inhabitants to a small archipelago of quasi-futuristic-looking platforms. It is in many ways abstract and disconnected from what we would brand a "real" world; akin more to a simulation than something even an advanced civilisation would be able to orchestrate in the vacuum of deep space. It instead serves a solitary purpose: to be an open and clear arena for the Players to pull off dextereous ricochets and physics-bending leaps from one spot to the next. There are no other earthly rules to govern this world, and beyond the dark arena is the thrice as dark abyss.

Of course, by this logic, one could consider more abstract games along the lines of Tetris Effect or even Pinball Dreams, to also fit under the same umbrella of otherworldness, and I reckon they would be right. Both games take place in places foreign to our expectation for a, dare I say, traditional setting. This is not to say, oh no, that Otherlands belong to just the games -- far from it! Otherlands are to be found in many other media.

Off the top of my head, I'd count that one scene from the cult-classic 2001: A Space Odyssey, as a "classic" Otherland in a mind-boggling nutshell:

The message I'm trying to convey, if not clear, is that Otherlands are very stubborn, and insistent on breaking you as an earthly thinker; to augment your mind and let it comprehend and utilise the new reality and the rules it enforces, like one would use the laws of our universe. "When in Rome," is the mantra they will have you etch into memory, until you think and interact with it as though you had never known another home.

The entire world, in other words, is one big Twist, standing in stark contrast to the little twists applied here and there to an Earth-like dimension. Furthermore, one could even assert that the Twist in an Otherland is turned on its head -- whereas in an Earth-like Twists were other-landish phenomena many in number but little in scope -- the Twists in an Otherland are instead few and far between, and grounded in reality. They are the links linking an Otherland to the Earth-like law. Say, physics would be very much expected in an Earth-like world, but treated as an exotic Twist in an Otherland.

To be a little more precise, an Otherland does not bother to stay true to the mechanics we think mundane and natural. It instead moulds or kills them outright, and throws itself at the mercy of the designer's wants and wishes.

Otherlands were an option, but not the option, that I'd choose for my world. I cherish the freedom they bestow upon you as a designer, but it alone did not convince me to opt for this archetype. Simply put, the downs outweighed the ups:

The world I wish to create will host fantasy far too Tolkien-esque to distance so much from Earth and earthly law. There is, in my view, a strong pull among many dungeon-crawling aficionados towards fantasy, and fantasy I will deliver. My own strain of fantasy, to be clear, but it will nevertheless mandate a degree of reality deemed by me too Earth-like to belong in an Otherland. I just can not see, at this time, a world of fantasy that is also an Otherland, not if I want my world to radiate welcoming familiarity.

This game being an open-ended RPG, it is difficult for me to envision it in an abstract environment. It calls, as I see it, for landmarks sensible to someone never ever "tainted" by the quirks of Otherlands, familiar and homely in a way, based in laws of physics and around points of interest grounded in our reality. Elevating it to be the Twist of an Otherland, brings the latter much closer to an Earth-like, but not quite. Neither this nor that, if you will, and that in turn leads me to the next and last archetype...

Near-Earths

Should you ever run into the same predicament as yours truly did in the paragraph above, I'd strongly advise you to consider Near-Earths. Not entirely Earth-like, but also too Earth-like to fit as an Otherland, a Near-Earth world is based to some considerable extent in the laws and traits of an Earth-like. It takes the best of both worlds -- mind-boggling Twists of an Otherland and experiential familiarity of an Earth-like -- and mixes them up to shape up something in-between.

Near-Earth remains ultimately an extension of an Earth-like world at its core, but to set itself apart it puts an emphasis on large-scale Twists -- that would be considered too outlandish for an Earth-like. One popular trope among Near-Earths is to feature earthly topology, strewn around the universe in the form of isles or even whole continents. Fundamental laws that define an Earth-like it bends to a fictional degree, but preserves the essentials, such as planets or stars or faimiliar dimensions, that make up our universe. Thus the link between our universe and that lives on, and it's easy for a newcomer to the world to find their way around with little to no hand-holding required.

I can't help but conjure up a few shots from Treasure Planet, which I gather needs no introduction, to illustrate my line of thought. Take one of the more iconic stills from this flawed masterpiece, R.L.S. Legacy docked at the spaceport of Crescentia:

It is in many ways familiar, I think, to anyone who has ever been to any run-of-the-mill harbour, except that ginormous frigate appears to stay suspended mid-air, not even ropes to hold it in place, and not at all swaying side to side on the high seas as one would assume. No, in this universe carpenters and shipwrigts build 18th century vessels propelled by internal combustion engines to fly through the breathable expanse that they call Ethereum. Indeed, there it is possible to breathe in space, so long as one stays careful not to lean too much on the taffrail and fall into the Ethereum proper, doomed forever to be a cosmic castaway.

Treasure Planet is very representative of a Near-Earth world, as I reckon the aforementioned scene proves. While grounded in culture and (partly) science of our universe, it strays a lot from what our scientists would deem feasible, to the point that it is fundamentally different from our universe in some respect, such as there existing a breatheable atmosphere everywhere in their universe, but not so fundamental as to defy every law of science we know in our world. Physics, and planets, and other celestial bodies and phenomena still exist there, albeit altered in a variety of ways.

Another such example would the High Wilderness, that we're told to travel aboard a literal locomotive, in the brilliant game and one of my many favourites -- Sunless Skies:

It, too, features all the same biomes and structures and many laws with a basis in our universe, and like Treasure Planet, it introduces a major twist: the space beyond the confines of Earth (which does exist in Sunless Skies, and generally follows our history with significant deviations perpetrated by Masters of the Bazaar) is an intricate maze of seldom interlocked and often overlapping topology, stacked on top of one another, and filled with an atmosphere reminiscent of Ethereum, breathable but named a different name.

It is still familiar enough to us as earthlings, and it would not take a seasoned Otherlander to pick the thing up and know the rules of play by instinct. Sure, we are driving a locomotive through time and space, and pass by living stars that govern all, called the Judgements, but the spaces we traverse and people we meet and phenomena we witness are not confusing in the slightest. Shrouded in mystery, maybe, but ultimately sensisble if given enough thought. There is not another dimension for us to consider, and impossible geometry wrapping on itself to comprehend, as seen in Manifold Garden. Nay.

On the Judgements, as a side note, I've found them to be an interesting twist in and of themselves: they are intended to be the law-makers that decide what is real in this world, and what is not. Kill, or posses them, and the world will return to a chaotic state, easily a contender for the quintessential Otherland.

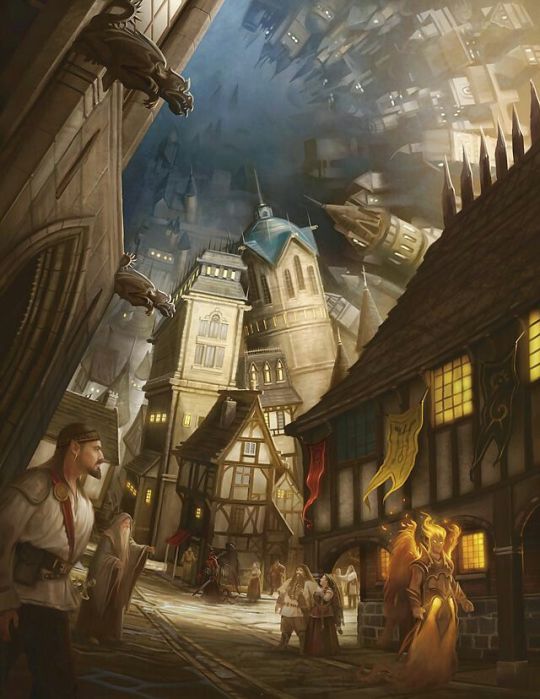

One last sample for you to taste would be the city-state of Sigil, the center of all planes in the planar world of Planescape (pardon the tautology!). Also an earthly world in many ways, it departs from tradition by dabbling in the ideas of interplanar travel, and whole planes of existence drifting from place to place depending on the belief of its denizens. Name me a single spiral-shaped medieval town suspended miles in the air:

I hope my criteria is now clear, or clear-er, better still if as a day. A Near-Earth has some of its fundamental laws thrown away, or meddled with, but there is always at least some foundation identical to that of an Earth-like.

Enter the Wild

In the end, I had a choice to make; a choice of three options, all of which bore pros and posed cons. Weighing all of them took me several restless nights, about a week in total, and some creative encouragement from a colleague, who suggested I turn to Sunless Skies-esque worlds for inspiration: islands floating in the sky, nurturing islanders and their peculiar settlements. I fell in love with the idea in a heartbeat, and on and on I went searching for references. It implied to me a Near-Earth, and all the marks of distinguishment I outlined before for other archetypes pointed to Near-Earths as the perfect fit for my world.

I settled for a few points of reference, among them...

Variably-sized islands and quasi-continents of Dragon Hungers, complete with pocket cultures and hosts of creatures that dwell there:

"Outdated" and outlandish means of transportation between the islands, like airships or fire-breathing dragons, a la Sunless Skies:

Celestial bodies of Treasure Planet, like black holes or nebulas, making an appearance, though toned down a bit to ditch some of their more destructive and lethal properties. A black hole wouldn't spaghettify you in the blink of an eye, but falling into one will nonetheless bring a swift (albeit not quite so fast and unavoidable) end to your career:

What they amounted to, ultimately, is an amalgamation of varied islands, some as big as a continent, others as small as my balcony, and all sporting ecosystems never-before-seen on most other islands. They are suspended in the sky, fortunate to have a man-friendly atmosphere, with a devilish twist I'd rather keep a secret for the time being.

Wannabe heroes make their living sailing through this sky aboard mighty airships or fire-breathing dragons (among many other means of transportation), from one island and on to the next, undertaking quests and accepting commissions from the locals to earn themselves some sustenance. It's a floating world of vagabonds, gallivanters, and legends-in-the-making.

OR! Those same gallivanters may find a particular island, or spot upon on the island, very tempting to settle on. Indeed, if they so desire, players would be able to adopt a sedentary lifestyle, and see what the wilds beyond the comfort of their heart might bring one treacherously blissful morning...

Us locals have entitled this universe the Wild. Enter at your own risk, traveller, for you may never return. This theme seemed to me like a good middle-ground between all the problems I've outlined reviewing archetypes:

Scope was confined to the typical bounds of an island. Some are bigger than others, no doubt, but all of them are a far cry from the usual dimensions of a continent. A narrow scope, as such, is a scope amiable to developers limited in number, or readiness to tackle an enormous landmass.

Narrowed scope in turn shortens the distance one must travel to leave one point of interest for another. We're feeding two birds with one scone -- there is no need for us, as developers, to fill up the lands betwixt with something for you to do, and you won't have to drag yourself through an overstretchesd piece of half-arsed (pardon my French) filler to finally reach the objective that caught your eye in the first place.

At last, as my colleague pointed out, islands in space are capital. Done before to be sure, that road has been travelled many times (and so were most others), but it is still the Earth-likes that proudly keep at the victorious spree as the dominant archetype among the developers. A Near-Earth to me felt like a fair and much-wanted change of scenery, for once in a blue moon.

A floating world shattered into many habitable pieces by far imposes so many more factors upon the cultures, languages, civilisation, technology, and nature of the wild, that to turn it down in favour of an all-too-researched Earth-like world seemed a lazy way out the massive creative problem, I think, many people of letters and pencil and other trades would be thrilled to approach.

P.S. I do realise all my scribbled judgements are arbitrary, and the lines separating Near-Earth from Earth-likes, from Otherlands, is apparently fine, and entirely subjective. These are little more than my five cents; my five thoughts on the subject, and I personally found grouping these worlds into archetypes a good "bookmark" that I've used and will likely come back to designing my own worlds. Peace.

4 notes

·

View notes