Text

I've moved websites!

The new home of televised birdwatching can be found over at substack: https://televisedbirdwatching.substack.com/

I will be leaving this website up, as a catalog of my past work.

The move to substack will allow email subscriptions to this blog, and makes commenting a lot easier.

Thanks, see you over there!

Tyler

0 notes

Text

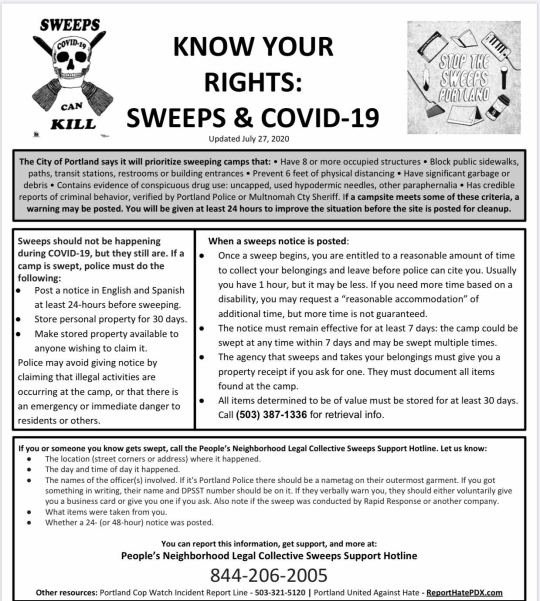

Mayor Wheeler's Camping Bans

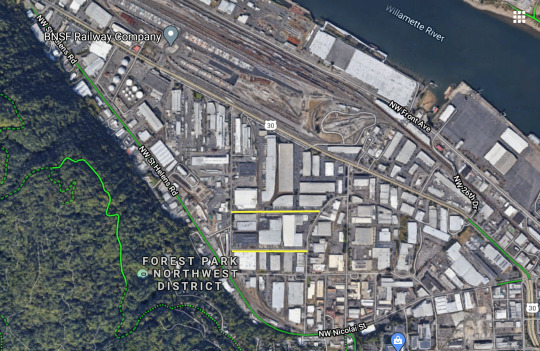

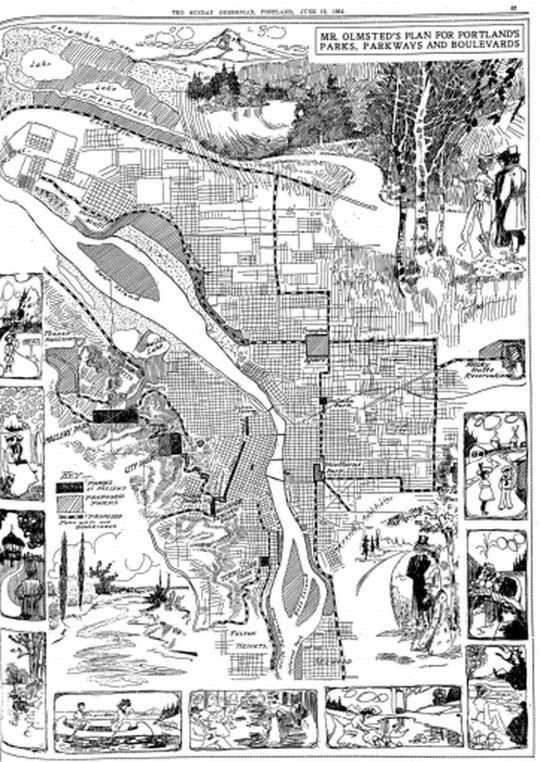

A few months ago, I created a storymap to show how the city of Portland's "homelessness impact reduction strategy" already made much of the city off-limits for homeless camping.

I have been taking an interactive web map class at Portland Community College and I used the skills I've learned to make an updated version with more interactivity and legibility, as well as stronger storytelling. You can see the updated version here:

https://storymaps.arcgis.com/stories/b4f099ecd6f94f1386502ac364db0112

0 notes

Text

Playing Journalist and Mapping Wetlands

Hello!

The past few months have taken me in directions that haven’t directly related to this blog, though I’ve still been working on plenty of projects. The wheelchair-related interviews I did over the summer have been hugely influential in creating momentum for the DIY wheelchair night, and the campaign for Ervin Jones is making progress. In addition, here are a few other things I have been up to:

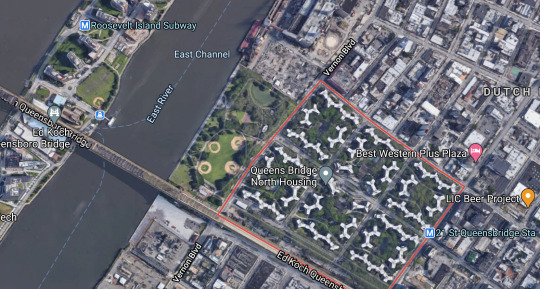

Swept With Nowhere to Go: ArcGIS Storymap

In August, I made a webmap using the ArcGIS Storymap platform. Portland’s mayor made an emergency declaration that unhoused campers along safe routes to school improvement zones would be prioritized for sweeps, and I wanted to show how this, among the other emergency declarations and exclusion zones, makes it nearly impossible to sleep while homeless in an area that is not in some sort of exclusion zone. Viewed geographically, you can also see how enforcement of these policies will push unhoused campers deeper into residential areas, increasing conflict between housed and unhoused neighbors.

I feel proud of the GIS and data work that went in to creating the page, but less proud of the writing and the design of the page itself. The GIS data I used to make the exclusion zone features on the map all came from public data sources, but not all of them were easy to find. The city and county both have websites where they host public GIS data, but some of the features, for example the wildfire hazard zone polygons and safe-routes-to-schools lines required some digging in the back end of the city’s Arcgis REST server. One of the successes of this project was learning how to do the digital detective work necessary to find and interact with the data.

However, I think the writing suffered from trying to address too many topics at once. For example, I wanted to do some homelessness mythbusting and make it clear that it is illegal to camp while homeless anywhere in the city of Portland. Because of Portland’s liberal reputation and visible homelessness, many right-wing media sources claim that Portland “allows” homeless camping. This isn’t true: visible homelessness is not the result of an overly permissive city, it is the result of a city that doesn’t have the police and prison resources to achieve their goals.

Second, I wanted to highlight how each of these policies, while sold to the public as measures to increase safety for homeless people, results in the increased criminalization of homeless people. For example, camps along high crash roads are prioritized for sweeps; this is supposed to reduce the number of unhoused people killed by cars each year. This is a good goal! But the result, police evicting campers from campsites along roads, ignores the fact that the only reason people set up camp along busy roads in the first place is because they have nowhere else to go.

Camps are also prioritized for removal if they are in wildfire hazard zones: again, a policy that makes sense at first glance, especially since fires at camps are common. But fires are common because people often burn trash, scrap wood, and pallets in homemade fire pits to stay warm and cook food. Campers could be given more appropriate fire containment systems like steel barrels cut in half, or they could be given fire extinguishers (something mutual aid groups have already done). But instead, the city sends in police to evict people, confiscate their belongings, and tell them to go somewhere else. Where, though? Shelters are full.

Lastly, I wanted users to be able to use the toggles on the map to be able to hide and show each exclusion zone. By turning them all on at once, you can see how individual policies, which may make sense at first glance, result in a system where there is nowhere left for people to exist while homeless.

I’m not sure my writing in the article was effective, and I was beaten to the scoop by mere hours: a few hours before I published my article, the Oregonian also released a map showing the same thing I did. However, theirs was not interactive, and also not complete: they did not include scenic and environmental zoning code areas like my map did.

Overall, I learned a lot about finding city data and using the ArcGIS Storymap platform for the first time. I wish my writing had been stronger and integrated the storymap platform features in a better way.

This week, I start night classes at Portland Community College again, where I’ll be taking a course in web-based mapping applications. I plan to use the skills I learn to re-do the storymap and to learn more about how to make interactive maps for the readers of this blog.

Bark! For Mt. Hood: Wetland Mapping

I have also been volunteering lately with an organization called Bark!, whose mission is to defend and restore Mt. Hood. They perform government watchdog operations, such as visiting proposed timber sales and verifying that the Forest Service’s claims about the site are accurate. They also have a legal team, and I’ve been working with a citizen science project that is mapping and groundtruthing wetland data.

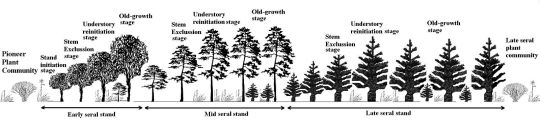

First, an environmental scientist at Portland State University uses satellite imagery to find and classify wetlands in the Mt. Hood area. Wetlands are classified by the type of water (marine, estuary, lakes, rivers, ponds), the type of vegetation present (trees, shrubs, submerged plants, etc), and the water regime (seasonal versus continuous saturation, eg). The environmental scientist makes educated guesses about these classifications for each wetland using satellite imagery, and then a group of volunteers led by a Bark employee go to the site in-person and verify that the wetland classification and map is accurate.

We document plant and animal types, take photographs, and take soil samples. The most fun part of these hikes is the opportunity to do environmental detective work: you learn how the presence of water stained leaves, algal crusts, and certain kinds of plants provide clues about the water regime in each area.

The verified wetland data is later used for various conservation-oriented uses. I’m excited to do more wetland mapping throughout this month and the next. If I can find the time, I am also considering volunteering to count salmon in the Johnson Creek watershed this winter. I am really glad to be doing something environmental again and for having a reason to hike around off-trail in the woods.

With school, work, and these projects, I'll be busy through the fall! I'll find the time to write updates as I get them.

Thank you!

0 notes

Text

Justice for Ervin Jones

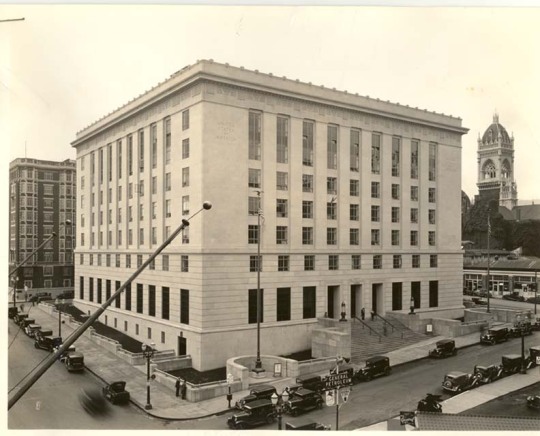

In April of 2021, I posted an article that I had been working on for a few months. The article was about the murder of Ervin Jones, a Black man, by police in Portland, 1945.

The first mention I heard of the Ervin Jones story was a single note in a Portland history book I was reading, but somehow it got stuck in my brain and I started researching. I found a few academic papers that reconstructed the events of the murder, and found out that public outcry and demand for justice in wake of the case helped coalesce the early civil rights movement in 1940’s and 50’s Portland.

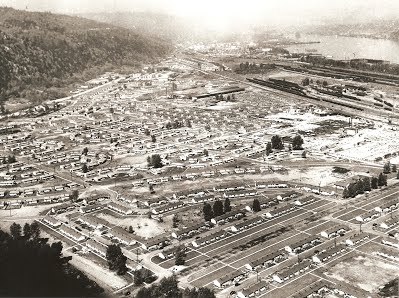

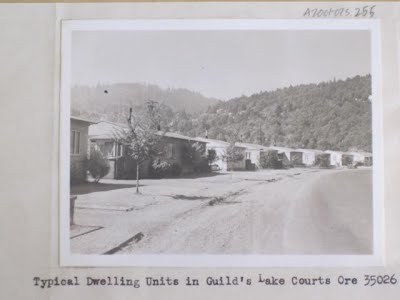

I also learned about Guild’s Lake Courts, the neighborhood where the Jones family lived, a wartime housing development and sister city to Vanport that housed 10,000 white and Black families at its peak in 1944. I couldn’t believe that an entire neighborhood of 10,000, in an area I frequently drove through, was something I had never heard mentioned before. So I started reading.

One of the reasons I couldn't let go of the Ervin Jones story was its similarities with the murder of Breonna Taylor. In both, plainclothes police were serving no-knock warrants in which they failed to announce themselves. In both, the residents of the home thought they were being robbed. In both, the person killed was innocent and not a suspect in any crime.

The officers involved in Ervin Jones’ murder were exonerated of all wrongdoing by an all-white jury. Ervin Jones’ death certificate lists his cause of death as “Justifiable Homicide.”

Learning the story of Ervin Jones showed me, in my whiteness and suburban upbringing, a lesson that I had to learn, that despite 80 years and thousands of miles of historical distance, the similarities in these stories weren't coincidence. They were evidence of the revolving wheel of systematic violence against the Black community.

Eventually I published an article on this blog, drawing from the academic and historical sources I could. I never expected that a few months later, I would get an email from the grandaughter of Ervin Jones.

Her name is Rhonda Winbush, and she lives near Shreveport, Louisiana, where her family returned after the traumatic events in Guild’s Lake. Her mother, Ardodia Jones Perry, and uncle, Ervin Jr, are survivors of the 1945 shooting. Ardodia was three years old at the time, and her head was grazed by one of the police officer’s bullets.

I started talking with Rhonda, and I referred her to an investigative journalist at Street Roots, to connect with the historians I had talked to and to dig even deeper into the story of Ervin Jones.

Street Root’s Melanie Henshaw published her incredible, in-depth, impeccably researched article on June 15th, and it can be found here.

To quote from the Street Roots article, “Rhonda, who has a daughter and granddaughter herself, and Ardodia, a doting grandmother and great-grandmother to them, want closure to this painful chapter. They’re calling on city officials to acknowledge Ervin’s death and condemn the city’s tacit endorsement of the police’s conduct.”

With Rhonda’s support, I have created a form letter you can use to help demand justice for Ervin Jones from city officials.

Dear [City Councilmember],

In 1945, plainclothes detectives from the Portland Police Bureau murdered Ervin Jones, a Black man, in his own home, in front of his family.

Despite the fact that police had no warrant, despite the fact that they were looking for a white suspect, despite the fact that they failed to identify themselves as police, and despite inconsistent testimonies in court, an all-white jury acquitted the officers of any wrongdoing and listed the cause of Ervin Jones’ death as a “justifiable homicide.” Following the trial, the Portland City Council voted to pay all legal fees incurred by the lead officer, but offered no assistance to Elva, the widow of Ervin Jones.

Today, the Jones family is asking for the justice our city failed to give them in 1945.

Ervin Jones brought his family to Portland in search of a better life, a dream never to be realized. After Ervin's murder, Elva moved the family back to Shreveport, Louisiana, where they live today. She and Ervin are survived by their children Ardodia and Ervin Jr., who were three and five at the time of the shooting, as well as their granddaughter Rhonda.

This is a family that could have stayed in Portland and become a part of our city’s vibrant social fabric, but were subject to racial violence and the generational trauma of 80 years without justice.

I am writing this letter to join Ervin Jones’ descendants in calling on you, as the city leaders of Portland, to acknowledge the injustice of Ervin’s death and remove his cause of death listed as a "justifiable homicide."

Sincerely,

[Your Name]

Mayor Ted Wheeler: [email protected]

Commissioner Mingus Mapps: [email protected]

Commissioner Carmen Rubio: [email protected]

Commissioner Jo Ann Hardesty: [email protected]

Commissioner Dan Ryan: [email protected]

District Attorney Mike Schmidt: [email protected]

0 notes

Text

DIY Powerchair Repair with Dan of Totally Normal

For a long time, I have wanted to connect with Dan Payton, the person behind the youtube channel Totally Normal. Dan is an expert in powerchair repair: in his videos, you can watch him repair lift and seating components, replace tires, and fix joystick centering errors. He also maintains a website, BrokenWheelchairs.com, where he provides links to any available technical manuals and error code documentation he can find.

I wanted to talk to Dan because I wanted to build my knowledge about power wheelchair repair, and after speaking with Madison Dennis about the (now-passed!) Colorado HB 1031, I was curious to hear his perspective on some right-to-repair questions.

Powerchairs can be intimidating to work on. My experience as a bicycle mechanic means I have enough background knowledge to be reasonably comfortable helping people with manual wheelchair repairs, but powerchairs include batteries, hydraulic lifts, and electric motors that add levels of complexity. Plus, some of the components are covered by plastic guards, which can hide fasteners and make the method of disassembly less than obvious.

So, I met up with Dan in his workspace near Portland, where we talked about all things powerchairs and repair. Almost 30 wheelchairs sit in the warehouse space. Some I recognize from vlogs, like the off-road powerchair, and others I don’t. He also shows me a workbench he has set up with software and cables from different powerchair brands and systems, allowing him to plug different components in, diagnose errors, and see how things work.

One of my favorite things about watching Dan’s vlogs is the joy and enthusiasm he brings to repairs and customizations. During our wheelchair maintenance workshops, people often approach issues with discomfort and unease, worried that they will make something worse in the process of fixing it, or end up in a repair that goes over their heads. When you’re talking about a mobility device that works as an extension of someone’s body, it’s easy to imagine the gravity of these concerns. But Dan's joy is infectious, and it's easy to see why he attracts youtube followers- he makes repair fun to watch, even when we're talking about crucial mobility devices.

DIY Powerchair Maintenance

In my last article, I shared a survey about power wheelchair repair from the Public Interest Research Group. One of the questions was: “Considering the problems or issues that prompted you to make a service request, what percentage of those do you feel could be performed by a friend, family member or independent repair professional with the right information, access to parts, etc.?” In his youtube videos, I’ve seen Dan perform some incredibly simple fixes: removing a plastic cover and cleaning something with rubbing alcohol, for example. But I’ve also seen Dan solder wires and customize software, so I wanted to get Dan’s perspective on the scope of DIY powerchair repairs.

First off, he says, pointing to one of the joystick control units used to operate powerchair functions, “The housing on these things, they just tend to break down and crack over time.” He shows me the screws that hold the plastic cover on the joystick unit, and the hex bolts that mount the plastic to the armrest. If replacement parts were available, this would be a relatively simple fix for a relatively common problem, and someone with a little bit of technical proficiency could probably handle it.

“Tires and caster wheels are also a regular thing everyone needs,” he says, noting that powerchair tires typically have a 6-month lifespan. He starts showing me how to access the bolts on a few different kinds of chairs. Most powerchairs use solid (non-pneumatic) tires, and the wheels separate into halves to facilitate install and removal. But each chair is a little different: he points to one chair where a plastic hubcap comes off to expose the wheel bolts, and shows me a different style where there are two plastic clips that need to be removed first.

With the wheel covers off, he asks “see that big yellow sticker there?” and points to a yellow warning sticker on a large bolt in the center of the wheel. “The manufacturer had to put that sticker there because when people were trying to change tires, some people would take this bolt off, and you do not want to take off this center bolt.”

It turns out, that big center bolt is used to set the bearing preload for the main drive wheels, similar to the way that a hub bolt works on a car, and then the axle uses a tapered fitting, so the bolt needs to be set to a very specific tension. Even if you're a mechanically inclined person, the large, obvious bolt in the center of the wheel seems like it needs to be removed in order to remove the wheel, but it doesn't, and doing so can cause problems. “But, the rest of it, if you’ve ever changed a tire on a bike, is pretty similar!” He shows me the bolts that mount the wheel onto the axle, and the other bolts which separate the rim halves from eachother.

He also mentions that changing batteries might be within the scope of what friends or family members could do, but we run into the same sorts of “yes, but” disclaimers. “It definitely depends on the brand,” he says.

“The chair next to you- you tilt it back, the front cover comes off, there are two connectors, and then the batteries literally slide right out.” But other brands aren’t so simple. “In other chairs, the batteries come out of the back, but there’s a lot of cabling and wiring down there, and it’s not blatantly obvious how it all comes apart.”

The theme here seems to be that many of the common maintenance tasks on powerchairs aren’t necessarily complicated, but there is some sort of “if” or “but” that keeps these things from being easy to DIY. For example, the plastic covers of control units are relatively easy to replace, if you can get parts from the manufacturer, which aren’t always available. Tires are easy to replace, however it may not be obvious which bolts connect to which parts of the wheel. Batteries can be easy to replace, but it’s not a standardized process between brands.

Without documentation and clear how-to guides, it is easy to see how a friend or family member could take a wrong turn and mess something up, even in these basic, routine maintenance tasks. But it’s also clear that not all maintenance issues require a technical mindset or specialized tools, and a little bit of how-to support goes a long way in making sure people can approach repairs comfortably, confidently, and safely.

Into the deep end: Powerchair Hacking

Beyond the regular and routine maintenance tasks, I also wanted to ask Dan about his experiences with customizing the functions of his chair. During our conversation, I came to really appreciate the pragmatic and measured way Dan approaches safety concerns.

“There are some hacks that are legitimately dangerous!” he says, and tells me about how the automatic parking brakes on powerchairs loudly click into place when the chair starts and stops moving. “That clicking is obviously obnoxious when you are in an environment with a bunch of people in chairs, or a quiet house or whatever,” so he figured out a way to bypass one of the chair’s sensors to prevent the parking brake from automatically engaging. He tells me that this can be great if you’re somewhere with level surfaces like the floors of your house, but if you forget to re-enable the automatic parking brake before you start heading down an accessibility ramp, the results could be disastrous!

“This is where I can see the manufacturer’s side of things,” he tells me. “I like to share how this stuff works and be able to get people going again, but at the same time, I don’t want to give people just enough tools to be able to get themselves into trouble.” He also mentions that on his website and in his repair guides, he leans into disclaimers pretty hard: he tells people “look, this will void your warranty, and unless you have a backup chair, if something goes wrong here, your chair is not going to work anymore.”

Through the course of our conversation, I developed a real appreciation for Dan’s approach. He clearly loves taking things apart, tweaking different variables, and is happy to test out customizations on himself; but he’s also someone who is keenly aware of the stakes at hand and does not encourage people to jump into the deep end of powerchair hacking unless they are really, really sure they want to do so.

“Right now, the way it is, you don’t want to go exploring in the software and programming of these chairs, until there is proper documentation that can tell you how things work and actually integrate together.” It’s entirely possible to do some sort of customization or enable some feature that will prevent the control box from communicating with the rest of the chair software, leaving you stranded, he mentions.

He tells me that sometimes, if there’s some sort of error, you may just get an error message on your screen, or the chair software will work, but only in a degraded mode. Other times, in order to reset after an error, users will need to turn their chair off and back on again, which can take more than 15 seconds. If you’re messing around with a backup chair in your own home, this might not be a huge problem, but if it happens to your primary chair while you’re in a crosswalk, the consequences could be much higher.

Navigating Risk

I left our meeting and drove home, my head swimming with ideas about powerchair repair. For one thing, I still had the feeling that powerchair repair just isn’t an obvious endeavor. The same way that you can’t tell what an alternator does just by opening the hood of a car and looking at one, it’s hard to tell where to start with a powerchair repair unless you have a little bit of background knowledge about how they work.

But I also left with an understanding that this doesn’t necessarily make powerchair repair intimidating or impossible; instead, it underlines the fact that people attempting DIY repair need a little bit of support: support like Dan explaining which bolts to loosen and which to leave untouched, or a schematic diagram showing how a control unit connects to an armrest.

As I’ve mentioned in other articles, DIY repair isn’t always something people do by choice. For people who live in rural areas or who don’t have the financial resources to pay for an ATP’s time, DIY repair might be a necessity, and hopefully the passage of Colorado’s HB 1031 will help give those people some of the support they need. Even if people aren’t attempting their own repairs, Dan’s vlogs still help people build technical literacy about how their devices work, which can help people advocate for themselves to their medical providers.

I also thought back to my conversation with Madison Dennis, where we talked about navigating safety and risk when repairing powered wheelchairs. “Our viewpoint at right to repair is not that people should be forced to work on their own wheelchairs that they aren’t comfortable with- it’s really just so people can navigate their own risks,” she said. Listening to Dan talk about testing things out on his own chair made me think about navigating risk, and what it means to trust wheelchair users to do that for themselves, instead of hiding service manuals and schematics from the users of these devices.

If you want to support Dan's wheelchair repair work, you can support him on patreon, become a youtube member, or use this amazon click-thru.

0 notes

Text

Colorado HB 1031, The Right to Repair Powered Wheelchairs, with Madison Dennis and PIRG

Right after we finished our presentation on wheelchair repair at The Street Trust’s Active Transportation Summit, I checked my inbox and saw that one of my co-presenters had forwarded me an email with a link to a survey about how Right to Repair legislation could impact the lives of wheelchair users. The email came from Madison Dennis, New Economy Associate at the Public Interest Research Group. I opened the link and was excited to see that many of the questions in the survey were pulling at the same threads we had just talked about in our presentation. I sent Dennis an email and asked for an interview.

The Public Interest Research Group or PIRG is part of a coalition pushing for the passage of HB 1031 in Colorado. This bill has already passed the state legislature and is on Governor Jared Polis’ desk awaiting a signature. This bill would establish a legal right to repair for powered wheelchairs, ensuring that Durable Medical Equipment manufacturers (DME’s) make repair manuals, specialized tools, and replacement parts available to powered wheelchair users at reasonable prices. Currently, DMEs hold tight control of these resources, monopolizing options for repair when a battery, seat cushion, or joystick needs to be replaced.

Passage of this bill would revolutionize the wheelchair repair industry, at least within the state of Colorado, and help balance power between DME companies and the users who depend on their devices. “When you rely on your power wheelchair for basic mobility, any delay or barrier to repair is a quality of life issue.” Dennis says. “It’s no longer just about basic consumer rights, it’s about giving people what they need so they can get to their healthcare, their work, or whatever it may be.”

Coalition Building and Surprising Allies

PIRG is part of a larger coalition built around creating and passing this legislation. The Colorado Cross-Disability Coalition has helped support this bill, and within the legislature it has found bipartisan support. The bill’s primary sponsor is representative David Ortiz, (D., Littleton) who uses a manual wheelchair himself. “Right to repair has a really remarkable group of people who are passionate about this issue,” says Dennis. “Some of them are just regular people who have technical skills and want to make the best use of the products they already have; some of them are repair professionals or people who have small businesses who feel like they are losing out on customers because manufacturers are basically trying to block you into fixing it through them, or buying new.”

I ask Dennis if there were any surprising allies within the coalition of supporters, and she talks about finding support from school administrators who were having trouble keeping their technology fleets up-to-date, and from digital divide activists trying to keep devices working so they can get them into the hands of people that need them instead of becoming e-waste.

Dennis pointed out that when you get into the nuts and bolts of this issue, you realize there really are no surprising allies, because right to repair affects everyone in some way. “Right to repair isn’t as accessible of an issue right off the bat as something like climate change, or saving the bees- it can be hard to understand at face value,” but when you consider the implications of these kinds of bills, you realize it’s really an extremely widespread issue that touches everyone in our community. “Every single person owns a phone, or has a technological device they rely on, or requires medical attention where they need a functioning ventilator, or needs a functioning tractor to provide food,” she says. Although this specific bill is limited to powered wheelchairs, it helps build momentum for the larger right to repair movement, the same way that Massachusetts’ 2012 Automotive Right to Repair bill helped lay groundwork for other right to repair bills in other states.

Safety & Trust

When we talk about the DIY Wheelchair Repair night we host, people often ask us how we make sure we’re not compromising wheelchair users’ safety; and I wasn’t surprised to see this coming up in news coverage of HB 1031. When reached for comment about repair, representatives from DME companies often say that wheelchairs are complex medical devices that shouldn’t be worked on by just anybody. I ask Dennis to talk about her experiences with this concern.

“Our viewpoint at right to repair is not that people should be forced to work on their own wheelchairs that they aren’t comfortable with- it’s really just so people can navigate their own risks. If you own it, it should be your decision, and if you don’t feel comfortable, then you should have the opportunity to wait for someone you trust. But if you don’t trust your normal provider to get it done right, or on time, we believe you should be able to make your own choices about when it gets done.”

Plus, Dennis points out, there are significant safety risks when your chair is broken, and people often don’t take those risks into account when considering overall safety. Wheelchair breakdowns cause loss of mobility, and forcing people to make do with broken equipment while they wait on technicians can cause injuries and other issues.

Denver’s CBS news station quoted Julie Reikin, a 30-year powerchair user, who said “The argument that’s most insulting to us is that people with disabilities will make mistakes and hurt ourselves. We’re not stupid.” Part of right to repair is trust: trusting that wheelchair users know what they need, whether that means calling in the professionals, or handling something on their own. “If we can be trusted to independently fix cars that we’re speeding down the freeway on, then we should also have that same option for these super critical mobility devices,” says Dennis.

Wait Times

One of the questions in the PIRG survey asks people about the average wait times they experience in the course of seeking wheelchair repairs from the companies’ official providers. When speaking with folks during our Wheelchair Repair nights, people often blame the companies for excessive wait times, but the companies blame Medicare and the insurance industry for complications that lead to slow service.

“I do think there are issues with the billing and the processing, and we’ve been working to make some of those changes, too.” says Dennis, pointing to a companion bill in Colorado. But she also points out that expanding access to service manuals, tools, and parts should increase the number of repair technicians, since small repair businesses could effectively compete with the manufacturer’s repair service. This could also help improve the levels of service for people who live in rural areas.

Right to repair is also a common topic in the agricultural equipment industry, and Dennis notes that if you happen to live close to a manufacturer-approved repair shop, these issues aren’t as widespread. “But there are tons of people who rely on these devices who are a hundred miles away from a manufacturer certified repair chain. It’s a lot of time, it’s a lot of delays, and we want repair to be accessible to everyone, not just the people who live nearby.”

Do It Yourself

Another of the questions in the PIRG survey asked people to consider the issues that prompted them to make a wheelchair service request, and estimate what percentage of those repairs “could be performed by a friend, family member or independent repair professional with the right information, access to parts, etc.?” In my next article, I’ll be speaking with Dan, who runs the youtube channel “Totally Normal” where he is a DIY educator on powered wheelchair repair. In his videos, I’ve watched him perform simple fixes that involve taking a cover off for cleaning, and also watched him tackle complex customizations that involve soldering and re-programming control boards. Given the wide range of issues that can affect modern power wheelchairs, I ask Dennis to talk a little about this question.

“Those of us who have been working on this issue, we have been collecting what we call repair horror stories from people who rely on these power wheelchairs,” she says, and “we were hearing from a lot of people about cases where the delays were strictly because they needed to have a battery or a wheel replaced, and those are things that could be pretty easily and cheaply replaced by independent fixers.” She also mentioned that of course, the survey is not complete, but listening to wheelchair users directly helped inform the questions they asked.

“We are curious organizers and we want to know the depth of the issue, beyond the one-off bill or the one-off answer, we want to know how these things impact the community, and hear as many of these horror story conversations as we can so we know how widespread this issue is, how it’s impacting people, and how we can create change.”

You can learn more about the PIRG’s Right to Repair campaign here.

If you are a manual or powered wheelchair user, you can find the Right to Repair survey, here.

Edit 6/18/22: the PIRG survey is complete and you can find the results here!

1 note

·

View note

Text

$276 Million Unspent

This morning I saw this headline from Oregon Public Broadcasting: ‘People are dying’ while state bureaucracy holds up Oregon treatment dollars, say Measure 110 proponents.

Measure 110 was a November 2020 statewide ballot measure to decriminalize possession of small amounts of drugs like methamphetamine and opiates. One of the other provisions in the bill diverted marijuana tax dollars to a fund that would be disbursed to drug addiction treatment and mental health facilities. But the OPB article reports that “the lion’s share of that money for the current two-year budget cycle — $276 million — has failed to reach providers.”

The oversight board responsible for distributing these funds was moved under the umbrella of the Oregon Health Authority, who have caused cascading bureaucratic nightmares that keep the volunteer council from getting anything done. From OPB, again: “Most recently, problems arose when the agency repeatedly sent grant application evaluations back to council members to re-do, saying they were incomplete. Eventually, the work became too burdensome for some of the volunteer council members, many of whom have full-time jobs and other obligations. ‘There were over 300 little boxes we had to fill — some were irrelevant, but they are requiring we put an answer there,’ council member Amy Madrigal told The Lund Report.”

These delays have real, ground-level impacts for nonprofits that depend on state funding. OPB quotes Central City Concern, one of the largest homlessness and addiction services providers in Portland, as saying they have empty beds they cannot fill because they are still waiting on the funding to support those programs. Tera Hurst, executive director of Health Justice Recovery Alliance, said “This is what happens when money goes out to communities of color,” she said. “All of a sudden, everybody wants to dot i’s and cross t’s even more, and we knew this was going to happen.”

___

The OPB article reminded me of a loose thread on my blog. In 2018, I started writing about the city of Boulder, Colorado’s “linkage fee.” A linkage fee is charged to developers when they build new market-rate developments, and the fee money goes into a housing trust. The housing trust is then tasked with distributing that money to various housing programs, whether they be supportive services like rent assistance or constructing brand new subsidized housing.

In 2018, the article I wrote was about the news that Boulder would begin charging developers $30 per square foot in linkage fees. Boulder also has a “cash-in-lieu” program, where developers can choose to either set aside 25% of the apartments they build as affordable, or not build any affordable units and pay into the housing fund. At the time of writing that article, the city reported that between 2010 and 2017, they had collected $47 million in cash-in-lieu fees.

But the loose thread in my article at the time was that I could never really figure out if or how they distributed any of that money. So today I did some digging.

First of all, all of the links in my blog post are dead. Some of them go to 401-restricted pages or 404-page not founds. Another one asks for login credentials, which I obviously do not have for www-static.bouldercolorado.gov. However, I did manage to find a Tableau Dashboard that documents all of the payments in to the housing fund from 1990 to April 2020:

According to them, the city has collected almost $130 million dollars in fees.

Again, this site does not list disbursements from this fund, only payments in. But what surprised me is that it lists due payments, even some dating back to 2015. Clicking through some of these due payments is bizarre. There’s one for a remodel on a BMW dealership warehouse, and one for a new airplane hanger by the local airport. There is a new 5-over-1 development near my first apartment in Boulder with $1,054,100 due in linkage fees from 2019. It is next-door to the office for tech company splunk, and located in the S’PARK market. I am incapable of making these things up.

When I buy groceries, I am not allowed to leave the store if I say “don’t charge me sales tax, I’ll pay it later.” I am also not allowed to skip paying my income taxes. If I default on my student loans I could have my wages garnished. Are there mechanisms are in place to make sure developers pay outstanding fees?

...

Despite my lucky tableau dashboard find, I couldn’t find a similar resource to catalog disbursements from the $130 million that the city of Boulder is sitting on. I tried looking through the city’s open data website but couldn’t find the info I was looking for. Some things were close; for example this dataset which lists grants made to community organizations, but not what I needed.

It feels conspiratorial and wrong to think that the city isn’t doing anything with the money. And yet; if I was a city manager who wanted to have the appearance of doing something about the housing affordability crisis without actually doing anything, it would be a pretty perfect plan to lazily collect exorbitant fees and then rarely, if ever, disburse them to affordable housing projects.

Or, maybe they aren’t just sitting on the money, and are actually investing it in worthwhile projects. But if so, I can’t find receipts.

...

People need relief now, whether from the opioid crisis or the housing crisis. I feel for the members of the Oregon measure 110 committee. They are people, many of whom have lived experience with addiction, who took on a volunteer obligation on top of their busy lives, just to help get money into the hands of people who need it. But they can’t; so $276 million dollars is just sitting. If this bottleneck isn’t resolved, service providers will start to close up shop or lay off staff.

Of course, there is going to be debate about the proper way to resolve crises. There are meaningful and important criticisms of housing market manipulations like linkage fees, and there are meaningful and important criticisms of the american rehab and addiction industries. To be clear, I think governments ought to take time to assess the impact of the programs they fund, to ensure that they are equitable and effective.

The part that feels criminal is the disparity between the urgency on the ground, the daily reality of folks who need help; and the canceled zoom meetings and pushed-back deadlines of the state government.

0 notes

Text

Nesting, Wintering, Sheltering, Learning

I. News Despair

Last week, I needed a news break. First, the Portland Bureau of Transportation (PBOT) revealed that that 70% of the people killed in pedestrian/traffic crashes in 2020 were homeless. This is a huge increase from already unacceptable 2019 levels, where 21% of pedestrians killed in traffic crashes were homeless. As a reminder, at any given time, only about 0.5% of Portland’s population is homeless.

In response to this, Portland Mayor Ted Wheeler announced an immediate ban of camping (read as: existing while homeless) along “high crash corridors.” It might make sense to think of this as a sensible knee-jerk policy reaction to help prevent further traffic deaths, but Wheeler’s approach targets the victims of vehicular manslaughter instead of targeting vehicles. Instead of increasing lighting or using traffic calming measures in high-risk areas, Wheeler used this as an opportunity to further his agenda of violently displacing unhoused people.

I’d also ask readers to consider this map of “Top 30 High Crash Streets” from PBOT, to see that Wheeler’s response effectively bans camping near any and all major streets in the entire city.

More info here if you're a maps & data person.

Also last week, Mayor Ted Wheeler and Commissioner Dan Ryan announced a ban on camping within 150 feet of the proposed “Safe Rest Villages,” city-sanctioned campsites, which themselves have been the subject of negative press for their ongoing delays. Ryan originally promised to have six “safe rest” sites open by the end of 2021. Two months into 2022, the only progress we’ve seen is an announcement about the proposed locations of three of the six sites.

Two days before the news about the traffic death report and the camping ban, the Oregonian published a survey showing that 95% of the unhoused people subject to sweeps were not offered shelter before being swept. It’s common to hear people assert that visibly homeless people are “homeless by choice,” suggesting that the folks who sleep outside are people who refuse to be helped when help is offered to them. There are many reasons why this assertion is wrong, but now we know that 95% of the time, help isn’t even being offered when the police show up and tell people to move along.

II. An Antidote to Despair?

My typical response to this particular brand of overwhelm is to bury myself deeper in my mutual aid projects. The worse things get, the more I feel motivated to help in some way. For the past few years I’ve volunteered with a local group of folks who run a mobile free store. Twice a week, they go around town offering tarps, sleeping bags, hot meals, clothing, harm reduction supplies, pet food, and first aid kits to our unhoused neighbors.

But this kind of work isn’t always the antidote to despair that it seems to promise. I read “Social Service or Social Change?” by Paul Kivel last year, and it still echoes through my head. In this essay from 2000, Kivel makes a distinction between social service work- work that “addresses the needs of individuals reeling from the personal and devastating impact of institutional systems of exploitation and violence” from social change work- work that challenges the roots of the systems of exploitation and violence.

Kivel creates this distinction after working with domestic violence shelters in Oakland, California. He notes that social service work is hugely important, writing “the needs and numbers of survivors are never ending, and the tasks of funding, staffing, and developing resources for our organizations to meet those needs are difficult, poorly supported, and even actively undermined by those with power and wealth in our society.”

But there is a crucial problem: addressing the needs of the survivors of domestic violence does nothing to end domestic violence in the first place. He notices that unless someone took on the social change work that addressed the root causes of patriarchal male violence, nothing was going to change.

Kivel does precisely this, establishing the Oakland Men’s Project to perform social change work ending the cycle of violence that creates domestic violence survivors in the first place. But the sentence that sticks with me is a sentence he quotes from the director of a women’s shelter: “We could continue doing what we are doing for another hundred years and the levels of violence would not change.”

Of course, the portrait of Kivel’s article that I’ve provided here is oversimplified, and I encourage everyone to give it a read for themselves. I think of it often. Is the work we do at the free store mere social service? Only a band-aid? If providing social service is so time-consuming and resource-intensive, how will we ever find the capacity to do social change work in addition to the service work we’re already doing?

III. Rosa Parks’ Birthday

February 4th, the day PBOT’s pedestrian fatality statistics were released, was also Rosa Parks’ birthday. To celebrate, Portland’s transit agency, Trimet, waived all bus and light rail fares.

It reminded me that before covid, my primary activism interest was transit, specifically a campaign to secure fareless transit across the Portland metro. At the time, multiple organizations were making a serious push for fareless transit, and it seemed like critical momentum was beginning to build. OPAL PDX, an environmental justice organization, had won an extension of bus transfer tickets from 2 to 2.5 hours, and then won victories to protect and expand youthpass, a program that gives K-12 students in Portland free transit passes. It felt like energy was building in a transit-oriented direction, and fareless transit was a possibility, not a far-off dream.

And then, covid struck. In the early days of the virus, before everyone began masking, I remember seeing uneasy looks on public transit on my way to work. And then when the virus made its full weight known, transit ridership declined sharply. A staffing shortage of operators led to a 10% reduction in service, and then Trimet limited the number of passengers on buses to enable distancing. The result was long wait times for a bus that may or may not have the capacity to let you on.

It was in this climate that voters in Portland metro rejected Measure 26-218, a transit bond that would have helped fund major transit projects for the next 15-20 years. Covid wasn’t the only reason for a decline in transit enthusiasm, and as these headwinds stacked on top of eachother I gave up on transit activism. I dug deeper into disability and homelessness related things instead.

IV. Myles Horton Learns from the Birds

Last month I read “The Long Haul,” an autobiography of labor and civil rights organizer Myles Horton, reflecting on his lifetime of activist work. Towards the end of the book, he included a small chapter about birds and headwinds. I will post some of it, here:

“As I read about birds, I realized that they not only use tail winds but they don't fight the winds. They change their course year after year on the basis of the particular situation. They never come back exactly the same way twice because the conditions are never the same, but they always get to their destination. They have a purpose, a goal. They know where they are going, but they zigzag and they change tactics according to the situation. I thought, for God's sake they're pretty smart, why can't we learn not to do things when it's almost impossible? Why can't we learn to hole up and renew our strength? Why can't we learn to change the entire route if it's necessary, so long as we get to the right point? I started learning from the birds about how to conserve energy and how not to wear myself out. I also learned how to take advantage of crisis situations and of the opposition and use that knowledge for my own purposes. Once I did that, it became a little easier to program ideas and survive, and to begin to share that kind of thinking with other people in a way they could understand.

Now sometimes even birds make the wrong analysis and fly into a storm. They have to fly against the wind, but after a while they stop fighting it and find a place to land and hole up. They don't try the impossible. I think that's very important in movements. There are times when you can't go ahead. It's not within your power to deal with it, because the forces out there are such that you can't. You're not superhuman, and it's beyond your power. That's the time to hole up and start thinking. You watch the wind, and wait for it to blow your way.”

Rosa Parks attended trainings at Highlander, the school founded by Myles Horton and friends. I remember being told about Rosa Parks in school, and the way the story was taught to me was that Parks was just a regular person who made a spontaneous choice not to move to the back of the bus.

That story isn’t right. Not only was Parks attending organizer trainings, she had been a member of the Montgomery NAACP since 1932, and had been the executive secretary since 1950. In this time she had worked on voting rights campaigns and campaigns to help clear the names of young Black men falsely accused of rape. She was well known as a civil rights activist in Montgomery and beyond.

Horton writes about his conversations with Parks after the bus boycott. Parks admitted to Horton that her decision not to move to the back of the bus was not prearranged and that she acted individually; so in that sense it is true that her action was spontaneous. But Horton continues: “Parks operated with the full knowledge that for at least two years black people in Montgomery had been trying to set up a test case on the segregated buses… With that knowledge, Rosa wasn't only acting as an individual, she was acting in a way that was consistent with the beliefs of the black organizations in Montgomery, just as she was sent to a Highlander workshop by some of the same organizations.”

The Montgomery Bus Boycott itself wasn’t the first of its kind. Two years earlier, the Baton Rouge Bus Boycott gave people the opportunity to learn what it takes to run a successful bus boycott campaign. People had practice, and were able to share strategies with their peers. Black taxi drivers lowered their rates to help people get around town without using buses. Black women created support networks to ensure that kids got to school without using buses. These systems of cooperation and support don’t spring up out of nowhere, even if your history textbook wants you to think so. Organization requires coordination, planning, and cooperation; skills learned through practice.

Montgomery, Alabama 1955 was a time with particularly strong Civil Rights tailwinds combined with an organized, mobilized, cooperative community of Black activists who knew what they needed to do in order to target the levers of power and achieve real gains. When Parks refused to move to the back of the bus, she did so as an organizer, making a targeted move that capitalized on the community’s power.

V. Nesting, Wintering, Sharing, Learning

All of this makes me wonder about what Parks’ life looked like from 1932 to 1955; what it looked like in the years of planning, learning, preparing, and building power within the community.

The headwinds proved too strong for transit activism in Portland 2020, and maybe I’m starting to recognize strong headwinds in housing activism in 2022.

Things have been rough. Our little mutual aid group has helped people weather two extreme wildfire smoke events, two extreme cold events, one heatwave, and a global pandemic, on top of the routine violence that comes from policing, sweeps, and the housing market.

Horton’s book helped me reframe the defeat I feel when I think about Kivel’s social change/social service distinction. Horton tells us that sometimes, the best thing to do is to hole up in our nests and wait for more favorable conditions. Perhaps social service is the best we can do right now.

And while we’re all nesting together, we can talk. Share strategies. Share our experiences. Share the skills we’ve learned. And meanwhile, continue caring for the folks in our neighborhoods.

“Mutual aid work plays an immediate role in helping us get through crises, but it also has the potential to build the skills and capacities we need for an entirely new way of living at a moment when we must transform our society or face intensive, uneven suffering followed vy species extinction. As we deliver groceries, participate in meetings, sew masks, write letters to prisoners, apply bandages, facilitate relationship skills classes, learn how to protect our work from surveillance, plant gardens, and change diapers, we are strengthening our ability to outnumber the police and military, protect our communities, and build systems that make sure everyone can have food housing medicine, dignity, connection, belonging, and creativity in their lives. That is the world we are fighting for. That is the world we can win.” Dean Spade, Mutual Aid: Building Solidarity During this Crisis and the Next”

0 notes

Text

Wheelchair Maintenance and Repair Justice

Hello everyone, this is the first episode of my blog that I have done an audio version of. I hope you enjoy it! I wanted to do this because I know that long-form text isn’t accessible to everyone, so I’m trying to play around with a new format. This also means that if you prefer to read instead of listen, you can find the full text and clickable links as well as images on (here) my normal blog page.

I wrote this article based on my experiences helping to facilitate a DIY wheelchair repair workshop series. This has been an article I have been working on for a very long time and then in November, we got the chance to present some of this content to an audience of bicycle co-ops at the Bike!Bike! International conference, and that presentation was the jumping off point for this article.

At the end, you can hear my liner notes going through some of what didn’t make it in to this article and talking a little bit about other avenues I’d like to explore. Without any more intro, here you go:

It was a September evening and the sun was setting on one of the first cool days of the fall season. I was headed to Station 162, an apartment complex in East Portland, where we were hosting one of our monthly DIY Wheelchair Maintenance workshops. These apartments are managed by a property company that develops units designed specifically for wheelchair users, and we’ve asked to use their community room to host tonight’s workshop. The only parking spot I could find was on the opposite side of the busy five-lane street, and I waited for a gap in traffic to dash across.

For a few years now I’ve been volunteering at these wheelchair maintenance nights, organized as a collaborative effort between The Bike Farm and Oregon SCI. The Bike Farm is a community bike shop here in Portland, Oregon. Anyone can use the Bike Farm’s workshop space for $5 per hour, and used parts and bicycles are available for purchase. Community bike shops are also a knowledge resource. If you come in with squeaky brakes or a bike that won’t shift gears, friendly volunteers are there to help you diagnose and fix it.

Oregon Spinal Cord Injury Connection (SCI) is a nonprofit community health organization that exists to promote health, build community, and create opportunity for people affected by spinal cord injury. They believe that everyone who sustains a spinal cord injury deserves the care and community they need to thrive. Led by people with spinal cord injuries, they organize meetups, educational events, and offer counseling and support.

Outside, I meet up with my co-volunteers, Alison and West. The idea for wheelchair maintenance night came when Alison was tabling for the Bike Farm at a transportation and mobility conference. A wheelchair user approached the booth. After hearing about the co-op, he said he wished he could learn to work on his own wheelchair the way that cyclists can use the bike farm to learn to work on their bikes. This got Alison thinking, and soon after, she met West, who runs Oregon SCI. Their conversations resulted in the first wheelchair maintenance workshops.

I met Alison and West when I was volunteering at Street Roots, a local newspaper sold by unhoused Portlanders. At the time, I was working at the front desk, and one of the newspaper vendors asked me if I knew who to call in order to get his power wheelchair fixed: his charging cord had gotten damaged by the elements and now the batteries weren’t charging correctly. For unhoused people, it’s often difficult to get a cell phone fully charged, let alone a power wheelchair, and I had no idea who to call to get this person help. I started looking for resources and came across a flyer for Alison and West’s wheelchair event.

A flyer. White headlining text says Wheelchair Maintenance Workshop. Orange subtitle text explains the event is hosted monthly on 3rd Thursdays at rotating locations. The Oregon SCI and Bike Farm logos are at the top of the page. A big diagonal stripe reveals an image of a woman working on a wheelchair suspended on a stand. She is reaching her hands towards the hub of one of the wheels.

Alison knew that I came from a background in bicycle repair, and encouraged me to come to one of the repair nights, thinking I might be able to apply some of my bicycle experience to wheelchairs. I started showing up regularly, and I started talking to wheelchair users about their experiences with repair. What started as a question about where to get powerchair batteries and chargers replaced led me down a rabbit hole.

NoMotion

When wheelchairs or other durable medical equipment (like walkers and rollators) need to be repaired, you call an ATP, an assistive technology professional. Both private and public insurance companies require wheelchair service and repairs to be done by licensed ATPs. But the world of wheelchair repair is complicated, slow, and expensive, putting undue burdens on disabled people. Tasks that might take a bicycle mechanic under 2 hours to complete might cost between $60 and $120. Similar tasks performed by ATPs might take 6-8 months and could cost between $500 and $3000.

Like so many facets of the American healthcare system, the companies that employ ATPs are engaged in a race to the bottom that drives up costs, extends wait times, and reduces the quality of service experienced by wheelchair users. Companies like Numotion and Belleview Medical compete to underbid each other for government service contracts that cover broad geographical territories. I spoke with Grant Miller of The Curiosity Paradox who told us that the quality of wheelchair repair in the Portland area has seriously declined over the past 20 years. “A lot of small repair places have been bought by national chains, who are notoriously overburdened with requests, under resourced with technicians, and seemingly indifferent to the burdens their operation puts on our community.”

Many wheelchair users refer to Numotion as “Nomotion,” and their Portland area headquarters maintains a 1.6-star rating on google. Since wheelchair repair must be performed by an ATP, and since insurance network systems limit people’s options for care, wheelchair users don’t have alternatives.

Grant continued: “I have had repair people show up unscheduled at my house when I was not around, then charge me for their labor. They have also charged me for equipment I never requested. Repairs can take anywhere between six months to nine months. For some friends who rely on their wheelchair full-time, this means that they completely lack access to their lives. Technicians can be hit or miss, but are usually non-disabled. They ask people to set aside an entire day to wait for them and will often only give 20 minutes notice before arriving. I continue to have unfinished repairs from a process that was started over a year and a half ago.”

According to research by Worobey et. al, they found a 7.8% increase in the number of wheelchair users surveyed who needed repairs, and they found a 23.5% increase in the number of participants reporting adverse consequences from a breakdown, compared against studies done in 2004 and 2006. This report also shows that minorities and power wheelchair users experience more repairs and reported a higher number of consequences, compared against all others in the study.

Guilty until proven innocent

Making an appointment with an ATP is not necessarily a straightforward proposition. Complex bureaucratic barriers to care have been set up by insurance companies and government agencies which require wheelchair users to prove the medical necessity of their devices.

In 2019 I interviewed Mick, a 35-year veteran of the assistive technology industry, who described how Health Care Procedure Codes (HCPCs) slow down the process of getting people access to the devices they need. “As an example,” he said, “a standard high strength lightweight wheelchair is coded as a K0005. There is an allowable sum for the chair which includes basic functions, like wheel locks, wheels, tires, upholstery, and so on. If there is a medical need outside of the standard package, there is another HCPC associated with it. Height adjustable armrest are K0026, anti-tip wheels, positioning belts, seating components, etc. all have their own codes as well.”

Insurance companies typically require each separate HCPC to have its own documented medical necessity in order to be covered. This documentation can include notes from therapists, doctors, and charts that establish a history of need. Often times these long paper trails cause confusion, which can lead to a delay in approval. Someone who needs a lightweight wheelchair with height adjustable armrests and a custom seat has a difficult task ahead of them to prove medical necessity for each of these items. The PDF that I have linked, here is a four-page worksheet that shows some of the documentation required.

This image is a screenshot from the first page of a manual wheelchair documentation checklist. It takes the form of a bulleted checklist. It begins with “Standard Written Order (SWO) that contains all of the following elements” and then lists those elements and their acceptance criteria. This image was intended to show the overwhelming and confusing nature of these documents.

After the passage of The Affordable Care Act in 2011, Medicare began requiring face to face, in-person, documented encounters between people and their care providers for durable medical equipment services. There are state laws, too, like Oregon’s Rule 410-122-0090 which states that “for initial ordering of DME (durable medical equipment) items identified in section (5) of this rule, an in-person face-to-face encounter that is related to the primary reason the client requires the medical equipment or supplies must occur no more than six months prior to the start of services.”

The ostensible purpose of this requirement was to ensure that doctors were not sending claims for DME’s, hospice, and home care to insurance without actually meeting with their patient. Theoretically, this doesn’t seem unreasonable, but the effects of this requirement as experienced by disabled people seeking care is that the face-to-face requirement is a huge hurdle on the path to accessing care. It feels like this law comes from a deep and sad cultural fear that assumes that if taxpayer-funded benefit systems exist, they are going to be abused by people making false claims.

The system we’ve created- this system that requires wheelchair users and other disabled people to prove medical necessity for every line item of their care, and which requires people to have face-to-face meetings with their doctors in order to prove that they aren’t abusing public benefits by asking for anti-tip bars on their wheelchairs- is a system which is based on a fundamental presumption that disabled people are guilty until proven innocent, which further entrenches an antagonistic relationship between patients and the medical system.

This photograph was taken at a pre-pandemic wheelchair night. In the foreground, three people are working together on the rear wheel of an adaptive handcycle. In the background, you can see the controlled chaos of parts bins, tires, and accessories in the bike farm space. One of the best things about DIY wheelchair night is that it returns people to the fundamentals of care: it cuts out these barriers and allows people to directly access the support they need. Photo credit Eric Thornburg.

Medical Necessity and Accessories

Medical Necessity also shows up as a barrier when wheelchair users are looking for accessories that can make improvements to their independence and quality of life. Take for example the SmartDrive MX2 by Permobil. The SmartDrive is a lightweight, battery powered wheel that attaches to the rear axle of a wheelchair. Controlled via an app or a watch, the SmartDrive system gives manual wheelchair users an electric boost, which can be helpful for navigating hilly terrain or steep ramps. This product costs around $6,000.

If you would like for insurance to cover the cost of your SmartDrive, it is HCPC E0986 if you were wondering, you’ll need to prove medical necessity for it. But medical necessity is always going to be a subjective and external evaluation. An accessory like this could substantially improve the independence of a wheelchair user trying to navigate an urban landscape that continues to deprioritize accessibility for those who use wheels- but our system is built so that a doctor is needed to decide if this is necessary. It seems to me that any person’s success must require hours of tireless self-advocacy and research in order to submit the best possible case to the cold logical workings of the medical system.

This image is an advertisement for the SmartDrive by Permobil. It is a small arm with a wheel on the end of it, connecting to the rear axle of a purple wheelchair. You can also see a handle on top of the drive unit for moving the SmartDrive out of the way when not using it.

"And so, it changed the course of my life, and I, instead of becoming a developmental psychologist and working with kids, I went to law school and public health school, graduate school in public health, to learn how to survive, literally just learn how to survive the systems that disabled and chronically ill folks in this country are forced to navigate. And it also is now my day job.” Matthew Cortland, senior fellow at Data for Progress and cofounder of the #DemolishDisabledPoverty campaign, from an interview here.

For people who don’t have systems of support in their lives that enable them to be their own healthcare counselor and advocate, and for people whose lived experience contains any level of nuance beyond what the medical necessity system can handle, medical necessity barriers can keep people from accessing the assistive technology they need and force them to seek out wheelchairs and medical devices out-of-pocket or secondhand. This is also true for people who are uninsured or underinsured who have no opportunity for a mobility device to be subsidized.

Through wheelchair night, we’ve met people with chronic pain who explained how their wheelchairs provided support on days where walking was difficult, but how this wasn’t enough to qualify for medical necessity. We’ve also met people who found used wheelchairs online through craigslist or disability support facebook groups, and who needed help adjusting these devices to their bodies and getting them into usable condition. For people in these kinds of cases and others, the usual avenues for wheelchair repair are inaccessible.

A person sits in a wheelchair with a red and white frame and silver wheels. This person secured this wheelchair secondhand, and we helped adjust the tilt of the front wheels and the position of the rear axle for their comfort.

Disability and Enforced Poverty

Wheelchair repair can also be financially inaccessible for disabled people, especially those living on federal disability benefits. The average monthly payment received by someone on Supplemental Security Insurance (SSI) is just $586. The maximum monthly payment is $794, which means that at most, people receiving SSI benefits are getting about $200 per week. In order to continue receiving these benefits, people are also subject to a strict asset cap of $2000 as an individual or $3000 as a couple. This cap on couple’s assets mean that many disabled people don’t legally marry their long-time partners. However, this also means they are unable to access their partner’s insurance benefits through work.

If these dollar amounts seem criminally low, it can partially be explained by the fact that they were last updated in 1989. But even still, current legislation in S.2065, the Supplemental Security Income Restoration Act of 2021, proposes that SSI payments should be raised to the federal poverty line. If this act passes, it would represent a step forward, but a shamefully small one, increasing the maximum possible SSI benefit to around $250 per week. Living in enforced poverty makes it difficult to find and keep housing, put food on the table, and save for emergencies like a wheelchair breakdown; and our legislators’ best proposal is to move people from sub-poverty to regular poverty levels.

“The disability community in America has faced systemic disenfranchisement in the form of what I would characterize as policy violence for generations. It's been happening in public. But it has often been ignored, sidelined, marginalized. Whether you're talking about from unconscionable barriers to healthcare, to income limits for those seeking accessible housing, to barriers to marry who you love, or whether you're talking about disparate impact on school discipline.” Representative Ayanna Pressley (D, MA 7th District) quoted here.

A Path Forward

It is clear that the current system lacks the immediacy that wheelchair users need in order to stay mobile. ATP appointments are costly. Appointment wait times are extreme. Medical necessity documentation and face-to-face requirements treat disabled people as guilty until proven innocent, and force them to expend time and effort proving and re-proving their need. People who are uninsured are stuck paying for expensive devices and repairs out of pocket, or are forced to choose from secondhand options that may not be ideal for their needs. People who use our country’s disability safety net are subject to enforced poverty, creating a further financial barrier to repair.

This pre-pandemic photo shows a group of people working on wheelchairs at the bike farm. One person is sitting in a wheelchair, one is standing and taking notes, one is kneeling on the ground. In the immediate foreground of the image, there is a wheelchair that has been tilted backwards and where the front caster wheels have been removed. This photo captures the fun and collaborative spirit of wheelchair maintenance night. Photo Eric Thornburg.

In the face of these factors, wheelchair users might choose to attempt DIY repairs, but doing so can be tricky and intimidating. West from Oregon SCI recently told us the story of his first attempts at cleaning his caster wheels when we presented at a conference. Removing the little bolts that hold the front wheels onto the wheelchair, he was worried he might drop one and have it roll under the couch and out of reach. Without a robust system for replacement parts, the cost of mistakes can be really high.

In our presentation, West reminded us that due to the nature of his spinal cord injury, he still has use of his hands, but that not every disabled person has the hand and body function to get leverage on wrenches or hold small parts like bolts and washers securely. Other folks might not live in a place where they have the proper tools at home, or a space to work on something that is potentially greasy and messy.

We believe that bicycle co-ops (also called community bike shops or CBS’s) are uniquely positioned to help fill gaps in care and reduce the challenges to DIY maintenance in order to provide wheelchair users with a better, more immediate way to have their repair needs met.

Our conference presentation was to an audience of community bike shops, and we tried to point out that most shops likely already have the tools and parts they would need in order to start their own DIY wheelchair night. Many wheelchair bolts are hex (or allen) bolts that are extremely common on bicycles. Many wheelchair wheels are spoked just like bicycle wheels, and can be trued (straightened) in the same way. Air compressors and tire levers can be used to install solid and pneumatic wheelchair tires. Many rollators and other wheeled mobility devices use lever and cable actuated brakes that can be repaired and adjusted just like bicycle brakes. As an organizer, I understand how limiting space can be when trying to create community events, but most co-ops have classroom and workshop spaces where they can facilitate events safely.

However we also recognize that wheelchair repair is new territory for bicycle co-ops, and there can be some intimidation when getting started. For bicycle mechanics interested in building their background knowledge of wheelchair mechanics and for wheelchair users interested in figuring out how to work on their mobility devices, we’ve found it’s best to start small, with basic maintenance.

Research done by Orozco et. al shows that many of the most common causes for wheelchair breakdowns are simple fixes, at least in mechanical terms. In their study, worn out tires and innertubes made up 17.1% of repairs alone. Loose positioning supports (16.4%), loose wheels and axles (6.4%), and loose powerchair controller boxes (4.7%) together combine to show that about a quarter of all wheelchair breakdowns could be prevented simply by tightening things that have come loose. This jumps to almost half of wheelchair breakdowns when we include fixing tires and tubes. These are things wheelchair users should not have to wait 6-8 months for an ATP appointment to fix.

And yet, our community-driven event is not intended to create an antagonistic relationship with ATPs by circumventing them. In fact, we’re hopeful that by helping wheelchair users take care of routine maintenance, we can reduce some of the strain on the existing ATP system. This would free up ATP’s time for people who have serious repair needs beyond the scope of what DIY maintenance can address.

And then, there are also people who are uninsured or who don’t meet medical necessity criteria for whom DIY repair and maintenance might be the only option. When folks are forced to buy secondhand wheelchairs, wheelchair users and bicycle mechanics can team up to adapt and adjust chairs to better fit their new owners. Bicycle co-ops can offer their space, tools, and parts to community members who want to help refurbish durable medical equipment in order to keep it in service- for example, replacing the grips, bearings, and brakes on an otherwise working rollator in order to facilitate passing it on to the next person who needs it.

An instagram post of a flyer. Title text says “Wheelchair Request!” on a blue background with purple stripes. The flyer is soliciting donations of intact, good condition wheelchairs. If you have one, you can reach out to Wheelchair Witches, a project of the PDX Disabled Support network, which helps field requests for wheelchairs from the community, and matches them to people who have wheelchairs to donate. I think bike co-ops can be meaningful partners to efforts like these by donating time, space, and tools to fix up wheelchairs and other mobility devices so they can be passed on.

Creating dedicated DIY spaces for wheelchair repair and maintenance can also provide a space for wheelchair customization. Co-ops can provide assistance for installing accessory devices like the Free Wheel, which lifts the front casters off the ground, or the electric assist SmartDrive. Through social media I found Sabine at Hell On Wheels Design, who makes these colorful wheelchair handle spikes among other mobility device customizations. They say “Mobility aids that match a person’s aesthetic and make them feel confident can make all the difference, especially for young or newly disabled people. Disability is not a bad word and it’s not bad to stand out in a crowd... The whole goal is to make disabled people feel more comfortable and confident in using their mobility aids.”

This photograph is from Sabine’s website, Hellonwheels.club, and shows one of the wheelchair handle spikes they make. The spikes in the image are studded into pink leather, and it forms a wrap that velcroes around a wheelchair push handle. These handle spikes serve as an opportunity to add some self-expression to wheelchairs and also serve as a reminder that nobody should ever touch anyone’s wheelchair unless express consent is given. Sabine also has a sponsorship page where people can financially sponsor community requests for mobility devices- more info here.

We envision a DIY wheelchair night that helps to build community- a place where folks can work on customization projects and on basic maintenance. A place where folks from the disability and bicycle communities can come together to share knowledge and create documentation like zines and videos that will help other people learn how to work on their own mobility devices. Our goal is to prefigure a system for wheelchair repair that trusts the wisdom and experience of disabled people, instead of requiring them to prove medical necessity at every turn. We can expand the scope of the existing infrastructure of community bike shops to help wheelchair users in ways that don’t present financial barriers to needed repairs. A better system for wheelchair repair is possible, and we don’t have to wait to start making it happen.

Our time at Station 162 is over, and I start packing up my toolbox. We helped tighten some loose bolts, diagnose a mystery squeaking noise coming from a back support, and cleaned chairs for some older women who were really excited to see the colors on the base of their powerchairs sparkle again. There are still some folks lingering in the community room. We talk about service dog training, and about ski resorts with sit-ski options. I rinse out some of our cleaning rags in the sink and watch as a service puppy in training annoys and older, soon-to-retire service dog.